Abstract

The host determinants that contribute to attenuation of the naturally occurring nonpathogenic strain of West Nile virus (WNV), the Kunjin strain (WNVKUN), remain unknown. Here, we show that compared to a highly pathogenic North American strain, WNVKUN exhibited an enhanced sensitivity to the antiviral effects of type I interferon. Our studies establish that the virulence of WNVKUN can be restored in cells and mice deficient in specific interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) or the common type I interferon receptor. Thus, WNVKUN is attenuated primarily through its enhanced restriction by type I interferon- and IRF-3-dependent mechanisms.

TEXT

West Nile Virus (WNV) is a positive-stranded RNA mosquito-borne virus in the Flaviviridae family and is responsible for sporadic outbreaks of encephalitis in humans worldwide (20). A highly pathogenic North American strain of WNV (WNVNY99) has emerged and has caused over 30,000 diagnosed human cases, including more than 1,000 deaths over the past decade (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/index.htm). In contrast to WNVNY99, the indigenous Australian strain of WNV, the Kunjin strain (WNVKUN), has limited pathogenic capacity, as only 18 nonfatal cases in humans have been reported since its discovery almost 50 years ago (10). Genomic sequence comparisons between WNVNY99 and WNVKUN reveal a close relationship, with 97.7% identity at the amino acid level and only 33 of 77 substitutions being nonconservative (references 14 and 23; M. Audsley and A. Khromykh, unpublished results). Although differences in structural protein N-linked glycosylation have been postulated to explain, in part, the lack of pathogenicity of WNVKUN (3, 22), no study has definitively described the mechanism of natural attenuation.

The pathogenesis of WNV is greatly influenced by the type I interferon (IFN) host response (7, 12, 21). While both WNVNY99 and WNVKUN can antagonize this response in vitro (reviewed in reference 8), WNVKUN is strongly attenuated in adult mice (2) and virulent only in very young mice, for which the host immune response to viruses has not fully matured. Although the less virulent phenotype of WNVKUN could be attributed to several factors, including its slightly delayed replication kinetics in C6/36 insect cells or Vero cells (data not shown), we hypothesized that the major part of its attenuation could be explained by its distinct interaction with the type I IFN response.

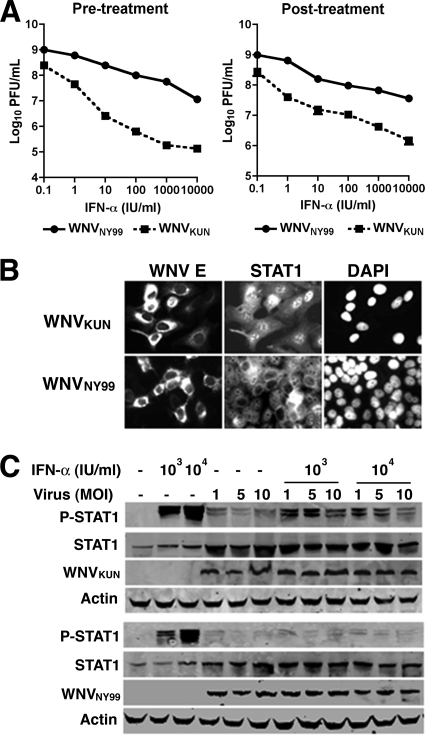

Prior experiments showed that both WNVNY99 and WNVKUN could limit the type I IFN response by blocking the phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 in cells (18). To define whether attenuation of WNVKUN was linked to a reduced capacity to replicate after the induction of an IFN response, human A549 cells were treated with increasing amounts of human alpha IFN (IFN-α; 100 to 104 IU/ml) 6 h prior to or 3 h after infection with WNVKUN or WNVNY99 generated from infectious cDNA clones (13) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Viral production was measured 24 h after infection by a plaque assay using BHK21-15 cells. Pretreatment with 100 to 104 IU/ml of IFN-α decreased the yield of WNVKUN 5- to 1,000-fold; in comparison, the same concentration of IFN-α reduced the infectivity of WNVNY99 only 1- to 50-fold (P < 0.05) in these cells (Fig. 1A, left panel). Similarly, treatment with 100 to 104 IU/ml of IFN-α 3 h after infection reduced WNVKUN titers 10- to 100-fold compared to 1- to 10-fold for WNVNY99 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A, right panel). Thus, WNVKUN exhibited enhanced sensitivity to IFN-α compared to WNVNY99 regardless of whether it was added before or after infection.

Fig. 1.

WNVKUN antagonizes IFN-α antiviral effects less efficiently than WNVNY99. (A) Effects of pre- or posttreatment of IFN-α on WNV production. A549 cells were treated with the indicated doses of IFN-α 6 h before (left panel) or 3 h after (right panel) infection with WNVKUN or WNVNY99, and virus production was evaluated at 24 h by plaque assay. (B) WNVKUN prevents IFN-α-dependent nuclear translocation of STAT1 less efficiently than WNVNY99. A549 cells were infected with WNVKUN or WNVNY99 for 48 h, treated with IFN-α for 30 min, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-WNV E and -STAT1 antibodies. DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (C) WNVKUN prevents IFN-α-dependent phosphorylation of STAT1 less efficiently than WNVNY99. A549 cells were infected with WNVKUN or WNVNY99 for 48 h, treated with IFN-α for 30 min, and lysed. Levels of phosphorylated STAT1 (P-STAT1), STAT1, WNV E, and actin were examined by immunoblot analysis.

Since the inhibition of IFN signaling by WNVNY99 and WNVKUN is mediated, in part, through the blockade of STAT1 and STAT2 activation, we hypothesized that the enhanced sensitivity to IFN-α may be due to a decreased capacity of WNVKUN to antagonize the IFN response by inhibiting these proteins. To evaluate this, A549 cells were infected with WNVKUN or WNVNY99 for 48 h and treated with 5,000 IU/ml of IFN-α for 30 min, and the levels of activated nuclear and phosphorylated STAT1 were assessed by an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or by immunoblotting. In WNVNY99-infected cells, nuclear localization of STAT1, in response to IFN-α treatment, was not detected by IFA, confirming that WNVNY99 efficiently antagonized IFN-α signaling. In contrast, in WNVKUN-infected cells, the percentage of infected cells with nuclear STAT1 was appreciably higher (Fig. 1B). Correspondingly, the level of phosphorylated STAT1 in WNVKUN-infected cells after IFN-α treatment was greater than that observed for WNVNY99-infected cells (Fig. 1C). Thus, in A549 cells, WNVKUN has an increased sensitivity to the antiviral effects of IFN-α compared to that of WNVNY99, due in part to a reduced relative capacity to block STAT1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation.

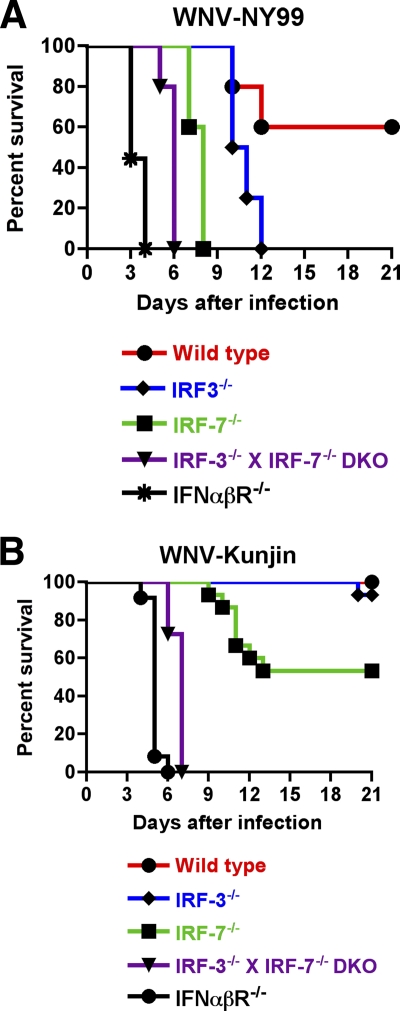

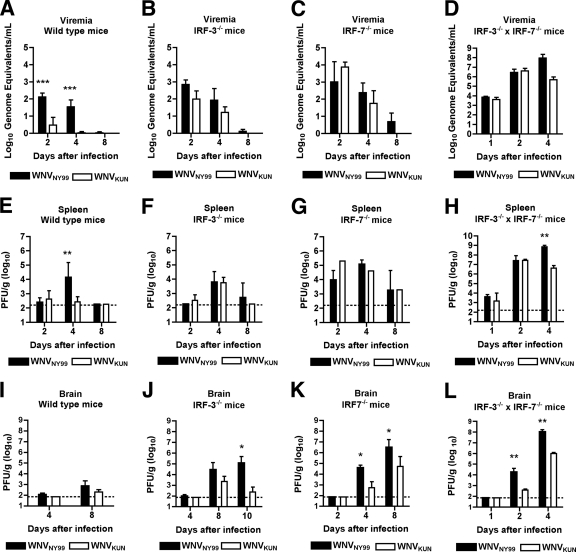

Since WNVKUN attenuation correlated with an enhanced sensitivity to IFN-α in vitro, we questioned whether the absence of host factors involved in IFN induction or signaling would restore WNVKUN pathogenesis in vivo. To evaluate this, 8- to 10-week-old wild-type, interferon regulatory factor 3 knockout (IRF-3−/−), IRF-7−/−, IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− double-knockout, and IFN-α/β receptor knockout (IFN-αβR−/−) C57BL/6 mice were infected subcutaneously with 103 PFU of Vero cell-derived WNVKUN or WNVNY99 and monitored for survival. Consistent with previous studies, wild-type mice infected with WNVNY99 exhibited an ∼60% survival rate (Fig. 2A) (5). In contrast, infection with WNVKUN resulted in no appreciable morbidity or mortality (Fig. 2B). Viral burden analysis of spleen and serum samples from wild-type mice at several time points after infection confirmed the attenuated phenotype of WNVKUN compared to that of WNVNY99 (Fig. 3A and E). Analogous to previous studies (7, 21), IFN-αβR−/− or IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− mice infected with WNVNY99 showed a 100% mortality rate with accelerated kinetics (mean time to death [MTD] of 3.4 ± 0.5 days [n = 9 mice] and 5.8 ± 0.4 days ([n = 10], respectively). Remarkably, infection of IFN-αβR−/− or IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− mice with WNVKUN resulted in a 100% mortality rate with only a slight delay in kinetics (MTD of 5.0 ± 0.4 days [n = 12] and 6.7 ± 0.5 days [n = 11], respectively) (Fig. 2B). Consistent with this result, viral titers from IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− mice infected with WNVKUN were markedly greater in all organs tested than those for wild-type mice, although in the brain, they did not reach those observed with WNVNY99 (Fig. 3D, H, and L).

Fig. 2.

Survival of mice infected with WNVKUN or WNVNY99. Eight- to 10-week-old wild-type and congenic deficient C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 103 PFU of WNVKUN or WNVNY99 by footpad injection and monitored for mortality for 21 days. (A) Survival data with IRF-3−/−, IRF-7−/−, IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/−, or IFN-αβR−/− mice infected with WNVNY99 were statistically different (P < 0.05) compared to those for the wild-type controls. (B) Survival data with IRF-7−/−, IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/−, and IFN-αβR−/− mice infected with WNVKUN were statistically different (P < 0.05) compared to those for the wild-type controls. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by the log- rank test.

Fig. 3.

Viral burden in peripheral and central nervous system (CNS) tissues from mice infected with WNVKUN or WNVNY99. WNV RNA in serum (A to D) and infectious WNV virus in the spleen (E to H) and brain (I to L) were determined from samples harvested on the indicated days using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR; serum) or viral plaque assay (spleen and brain). Data are shown as viral RNA equivalents or PFU per gram of tissue for 5 to 10 mice per time point. The error bars indicate standard error of the mean, and the dotted line represents the limit of sensitivity of the assay. Asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001) represent differences that are statistically significant by the Mann-Whitney test.

In comparison, infection of IRF-7−/− mice, which have a blunted systemic IFN-α response (6, 11), showed partial restoration of WNVKUN virulence, with an ∼47% mortality rate compared to 100% mortality after infection with WNVNY99 and delayed kinetics of death (MTD of dying animals, 11.0 + 1.3 days [n = 15]) (Fig. 2B). Replication of WNVKUN was enhanced in tissues from IRF-7−/− mice but also did not attain the levels in the brain observed for WNVNY99-infected IRF-7−/− mice. For example, although levels of WNVKUN were similar to those of WNVNY99 in the serum and spleen samples (Fig. 3C and G), the amount in the brain was ∼25- to 60-fold lower on days 4 and 8 after infection (Fig. 3K). This difference is likely because cells from IRF-7−/− mice still have an intact IFN-β response (6), which could limit WNVKUN virulence in a tissue-specific manner. A deficiency of IRF-3, which by itself does not affect WNV-induced production of type I IFN in some cells or in vivo (4, 5), did not restore WNVKUN virulence, as 93% (n = 15) of IRF-3−/− mice still survived infection. This compares with a 0% survival rate (n = 5) after infection with WNVNY99, as observed previously (5). Somewhat surprisingly, viral titers for the serum and spleen samples from IRF-3−/− mice infected with WNVKUN and WNVNY99 were comparable (Fig. 3B and F), although levels in the brain at day 10 were 400-fold lower in IRF-3−/− animals infected with WNVKUN (Fig. 3J), which likely explains the mortality results. Thus, IRF-3 had a differential and tissue-specific effect on the control of WNVNY99 and WNVKUN in the brain.

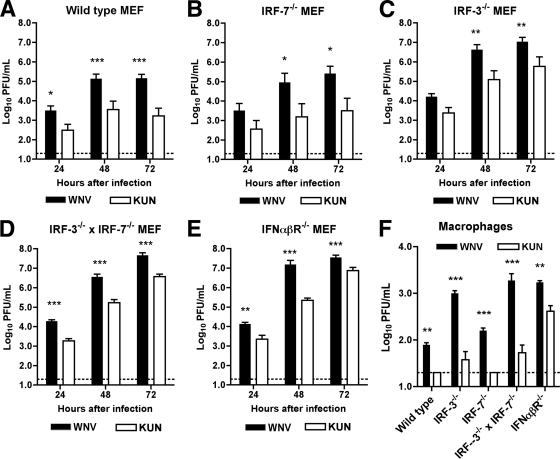

Since the attenuation of WNVKUN in vivo correlated with the integrity of key regulatory components of the type I IFN response, we evaluated whether WNVKUN and WNVNY99 replicated differently in primary cells, which produce and respond to type I IFN after WNV infection (6), and compared this to growth curves for congenic IRF-3−/−, IRF-7−/−, IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− or IFN-αβR−/− cells. In wild-type murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), multistep viral growth curves confirmed that WNVKUN replication was attenuated compared to that for WNVNY99 (∼10- to 80-fold decrease at 24 to 72 h postinfection; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, WNVKUN was attenuated (15- to 80-fold at 24 to 72 h postinfection; P < 0.05) in IRF-3−/− or IRF-7−/− MEF (Fig. 4B and C), which retain the capacity to produce IFN-α or -β after WNV infection (5, 6). WNVKUN still replicated less efficiently than WNVNY99 in IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− or IFN-αβR−/− MEF, which are either virtually or completely deficient in type I IFN signaling (7) (Fig. 4D and E). Thus, in MEF, a loss of the ability to produce or respond to type I IFN augments but does not restore the infectivity of WNVKUN to the levels observed with WNVNY99. This phenotype could be explained by differential expression of antiviral IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) in each of the deficient cells, some of which are induced differentially by IFN-dependent or IRF-3-dependent pathways (9). When we examined infection at 24 h in a second primary cell type, bone marrow-derived macrophages, we observed a similar phenotype: a complete loss of type I IFN signaling enhanced WNVKUN infectivity but not to the levels (4-fold lower; P < 0.01) observed with WNVNY99 (Fig. 4F). One apparent difference in macrophages was the relatively poor replication of WNVKUN in IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/− macrophages, which may be due to residual production of IFN-β in these cells after WNV infection through an IRF-3- and IRF-7-independent pathway (7).

Fig. 4.

Replication of WNVKUN and WNVNY99 in wild type, IRF-3−/−, IRF-7−/−, IRF-3−/− × IRF-7−/−, and IFN-αβR−/− cells. MEF or macrophages were generated as previously described (7) and infected with WNVKUN or WNVNY99 (MOI of 0.01), and virus production was evaluated by plaque assay at the indicated times for MEF or 24 h after infection for macrophages. Values are averages from triplicate samples generated for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean, dashed lines denote the limit of sensitivity, and asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001) represent differences that are statistically significant by an unpaired t test.

The experiments here establish that mice unable to produce or respond to type I IFN were vulnerable to infection with WNVKUN and suggest that the relative lack of pathogenicity of this natural virus variant in wild-type mice or, possibly, humans can be attributed, in part, to its rapid control by the host type I IFN response. Data obtained ex vivo using genetically deficient primary fibroblasts showed that an absence of the type I IFN enhanced WNVKUN viral replication but not to the level of WNVNY99; this correlated with a viral burden analysis of mice, which showed increased WNVKUN infectivity in genetically deficient animals that approached but was not equivalent to that for WNVNY99. One explanation of this discrepancy could be that subsets of cells and tissues differentially express ISGs through IFN-dependent and -independent (yet IRF-3-dependent) pathways (5). Although the genetic basis of the relative attenuation of WNVKUN remains a topic of further study, the phenotype is at least partially due to a reduced ability to antagonize IFN signaling and/or the antiviral activity of specific ISGs. Amino acid substitutions between both viruses are dispersed throughout the genome, with differences in the viral proteins NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS4A, NS4B, and E of WNVNY99 and WNVKUN identified as possible antagonists in IFN production or signaling (1, 15–19, 24). Recently, WNVNY99 but not WNVKUN NS5 has been identified as a potent inhibitor of IFN-dependent JAK-STAT signaling; remarkably, a single-amino-acid substitution in WNVKUN NS5 restored the inhibitory activity to that observed for WNVNY99 NS5 (15). Nonetheless, the exact contribution of each viral protein in inhibiting the host response in vivo and the identification of the specific molecular determinants that explain differential pathogenesis warrant further studies.

Acknowledgments

NIH grants U19 AI083019 (M.S.D), R01 AI074973 (M.S.D.), and UO1 AI066321 (A.A.K) and Australian NHMRC grant 511129 (A.A.K) supported this work. H.M.L was supported by an NIH Institutional training grant (T32-AI007172).

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arjona A., et al. 2007. West Nile virus envelope protein inhibits dsRNA-induced innate immune responses. J. Immunol. 179:8403–8409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beasley D. W., Li L., Suderman M. T., Barrett A. D. 2002. Mouse neuroinvasive phenotype of West Nile virus strains varies depending upon virus genotype. Virology 296:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beasley D. W., et al. 2005. Envelope protein glycosylation status influences mouse neuroinvasion phenotype of genetic lineage 1 West Nile virus strains. J. Virol. 79:8339–8347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bourne N., et al. 2007. Early production of type I interferon during West Nile virus infection: role for lymphoid tissues in IRF3-independent interferon production. J. Virol. 81:9100–9108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daffis S., Samuel M. A., Keller B. C., Gale M., Jr., Diamond M. S. 2007. Cell-specific IRF-3 responses protect against West Nile virus infection by interferon-dependent and independent mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 3:e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daffis S., et al. 2008. Interferon regulatory factor IRF-7 induces the antiviral alpha interferon response and protects against lethal West Nile virus infection. J. Virol. 82:8465–8475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daffis S., Suthar M. S., Szretter K. J., Gale M., Jr., Diamond M. S. 2009. Induction of IFN-beta and the innate antiviral response in myeloid cells occurs through an IPS-1-dependent signal that does not require IRF-3 and IRF-7. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diamond M. S. 2009. Mechanisms of evasion of the type I interferon antiviral response by flaviviruses. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grandvaux N., et al. 2002. Transcriptional profiling of interferon regulatory factor 3 target genes: direct involvement in the regulation of interferon-stimulated genes. J. Virol. 76:5532–5539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall R. A., Broom A. K., Smith D. W., Mackenzie J. S. 2002. The ecology and epidemiology of Kunjin virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 267:253–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Honda K., et al. 2005. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature 434:772–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keller B. C., et al. 2006. Resistance to alpha/beta interferon is a determinant of West Nile virus replication fitness and virulence. J. Virol. 80:9424–9434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khromykh A. A., Kenney M. T., Westaway E. G. 1998. trans-Complementation of flavivirus RNA polymerase gene NS5 by using Kunjin virus replicon-expressing BHK cells. J. Virol. 72:7270–7279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lanciotti R. S., et al. 2002. Complete genome sequences and phylogenetic analysis of West Nile virus strains isolated from the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Virology 298:96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laurent-Rolle M., et al. 2010. The NS5 protein of the virulent West Nile virus NY99 strain is a potent antagonist of type I interferon-mediated JAK-STAT signaling. J. Virol. 84:3503–3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu W. J., Chen H. B., Wang X. J., Huang H., Khromykh A. A. 2004. Analysis of adaptive mutations in Kunjin virus replicon RNA reveals a novel role for the flavivirus nonstructural protein NS2A in inhibition of beta interferon promoter-driven transcription. J. Virol. 78:12225–12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu W. J., et al. 2006. A single amino acid substitution in the West Nile virus nonstructural protein NS2A disables its ability to inhibit alpha/beta interferon induction and attenuates virus virulence in mice. J. Virol. 80:2396–2404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu W. J., et al. 2005. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the New York 99 strain and Kunjin subtype of West Nile virus involves blockage of STAT1 and STAT2 activation by nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 79:1934–1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muñoz-Jordán J. L., et al. 2005. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. J. Virol. 79:8004–8013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Petersen L. R., Marfin A. A., Gubler D. J. 2003. West Nile virus. JAMA 290:524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Samuel M. A., Diamond M. S. 2005. Alpha/beta interferon protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by restricting cellular tropism and enhancing neuronal survival. J. Virol. 79:13350–13361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scherret J. H., Mackenzie J. S., Khromykh A. A., Hall R. A. 2001. Biological significance of glycosylation of the envelope protein of Kunjin virus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 951:361–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scherret J. H., et al. 2001. The relationships between West Nile and Kunjin viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilson J. R., de Sessions P. F., Leon M. A., Scholle F. 2008. West Nile virus nonstructural protein 1 inhibits TLR3 signal transduction. J. Virol. 82:8262–8271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]