Abstract

Like all viruses, HIV-1 requires cellular host factors for replication. The mechanisms for production of progeny virions involving these host factors, however, are not fully understood. To better understand these mechanisms, we used a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) genetic screen to identify mutant strains in which HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane was aberrant. Of the 917 mutants identified, we selected 14 mutants whose missing genes had single orthologous counterparts in human and tested them for Gag-induced viruslike particle (VLP) release in yeast cells. We found that the Vps18 and Mon2 proteins were important for HIV-1 Gag-induced VLP release in yeast. In eukaryote cells, these host proteins are highly conserved and function in protein trafficking. Depletion of hVps18 or hMon2 reduced the efficient production of infectious HIV-1 virions in human cells. Our data suggest that these cellular factors play an important role in the efficient production of infectious HIV-1 virion particles.

INTRODUCTION

As part of their life cycle, viruses make use of the host's cellular machinery to replicate. After attaching to cell surface receptors, they penetrate the host cell, where, after uncoating, their viral genome is released for replication and transcription. Newly synthesized copies of the viral genome and viral proteins assemble to form progeny virions, leading to the release of infectious virion particles from the cells. Recent studies of the viral life cycle have shown that virus assembly is facilitated by usurping cellular pathways (3, 30). For example, for efficient particle release, HIV-1 Gag hijacks endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) via a Gag-Tsg101 interaction. Although the Gag-Tsg101 association is important for virus release, disruption of this interaction does not completely inhibit virion release (7, 50, 51). These observations suggest that other unknown host factors are involved in HIV-1 particle assembly and release.

For production of infectious HIV-1, the Gag protein associates with the cellular membrane, allowing budding from the cell surface. After particle release, a viral protease cleaves the Gag protein into four functional domains: p17 (MA), p24 (CA), p9 (NC), and p6, as well as two spacer peptides (SP1 and SP2) (42). The MA domain is required for membrane binding and envelope (Env) glycoprotein incorporation into virions. CA mediates the Gag-Gag interaction for Gag multimerization. The NC region recruits the HIV-1 genome into viral particles, and the small peptide, p6, is required for efficient virion production.

Recent progress in proteomics technology has shed light on previously unknown cellular factors and pathways that may be involved in virus replication (2). However, the roles of these cellular entities in the virus life cycle have yet to be verified in functional assays. Functional screening systems, such as yeast genetic variant libraries (52), offer an alternative strategy for identifying cellular factors involved in viral replication. In fact, yeast systems have been used successfully to identify several host factors involved in virus life cycles (29, 32, 36). Moreover, several groups have reported that this classic model organism supports some positive- and negative-strand virus replication (21, 32, 39). One such study showed that removal of the yeast cell wall leads to budding and release of HIV-1 Gag viruslike particles (VLPs) into the culture medium of the yeast cells (42), suggesting that yeast possesses cellular factors sufficient for HIV-1 Gag-mediated VLP budding.

To better understand the viral assembly mechanism, here, we used a Saccharomyces cerevisiae genetic variant library to identify host proteins involved in HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Vps18 and Mon2 were identified as having roles in HIV-1 Gag-induced VLP production in this yeast screen, and their importance in human cells was verified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293, HEK293T) and HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin solution (Sigma). The cells were grown in an incubator at 37°C under 5% CO2.

Plasmids.

Yeast expression plasmids pKT10-Gag (41) and pKT10-GagEGFP (49) and HIV-1 molecular clone pNL4-3 (1) were described previously. For expression of nonmyristoylated Gag protein, replacement of the N-terminal second glycine residue (GGT) to alanine (GCG) was carried out by using PCR-based mutagenesis. Yeast Vps18 and Mon2 cDNA was amplified from yeast genomic DNA prepared from wild-type yeast with appropriate primers and subcloned into a yeast multicopy plasmid modified from YEplac181 (13) so that Vps18 or Mon2 was expressed under a constitutive ADH1 promoter (unpublished data). To produce N-terminal FLAG-tagged hVps18 and C-terminal FLAG-tagged hMon2 constructs, their cDNAs were amplified from 293T cells by using reverse transcription-PCR with appropriate primers and cloned into pCAGGS/MCS (27, 34).

Western blot analysis.

Total cell lysates, as well as pelleted virus and VLP, lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, were resolved by using SDS-PAGE and detected with an anti-p24 mouse monoclonal antibody (48), a mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma), a mouse monoclonal anti-hVps18 antibody (Abnova, Taiwan), or a rabbit polyclonal anti-hMon2 peptide antibody. The rabbit hMon2 antibody was raised against 17 amino acids of hMon2 (1212TDSIGEKLGRYSSSEPP1228).

Yeast strains.

Yeast strain BY4743 (wild type [wt]) and a homozygous diploid deletion series (BY4743 background) (52) were purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL).

Visual screening of yeast mutants defective in Gag transport by use of fluorescence microscopy.

A yeast (S. cerevisiae) deletion library was transformed with pKT10-GagEGFP (containing the URA3 gene), which expresses the Gag protein fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) at its C terminus, by using the direct transformation kit Wako (Wako Pure Chemical, Japan). Yeast strains expressing pKT10-GagEGFP were grown overnight at 30°C in synthetic glucose medium lacking uracil, diluted to 1:50 to 1:100 with sterile water, transferred into glass-bottomed microplates (Greiner Bio-One, Germany), and examined with a Biozero BZ-8000 (Keyence, Japan) fluorescence microscope to determine the cellular localization of the Gag-eGFP fusion protein.

Preparation of yeast spheroplasts and purification of Gag VLPs.

These procedures were described previously (41). In brief, yeast transformants were grown at 30°C in synthetic glucose medium to stationary phase, harvested, and then washed once with distilled water and once with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 M sorbitol). The cells were then suspended in wash buffer containing 30 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and incubated at 30°C with gentle shaking. Spheroplast formation was carried out with Zymolyase 100-T (Seikagaku, Japan) in wash buffer containing 3 mM DTT for 20 min. Spheroplasts were washed twice with 1 M sorbitol and resuspended in YPD medium containing 1 M sorbitol and grown at 30°C for 16 to 24 h. Cultured supernatants were clarified and centrifuged through 20% sucrose cushions at 237,000 × g for 1.5 h. The pellets containing VLPs were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and analyzed by using Western blotting with a mouse anti-p24 monoclonal antibody.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis.

Two-hybrid analysis was performed with the Matchmaker Gal4 two-hybrid system 3 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech). Briefly, yeast cells were cotransformed with plasmids encoding the GAL4 activation domain fused to hVps18 or its deletion mutant construct or hMon2 or its deletion construct and the GAL4 binding domain fused to full-length Gag or the Gag domain. Cotransformed cells were spotted onto histidine-deficient or histidine-containing plates and incubated at 30°C for 2 to 3 days. Growth on histidine-deficient plates is indicative of an interaction between the two proteins.

siRNAs.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against human Vps18 and Mon2 (Invitrogen) corresponded to the following targets: nucleotides 1193 to 1217 (TCTGGCGCACCTATCTGGACATGAA) for hVps18 and nucleotides 4056 to 4080 (CATGCAGATAATGTATCCAGCTATA) for hMon2. The siRNA target sequence against Tsg101 was described previously (12). An siRNA against GFP (Invitrogen) served as a control.

HIV-1 virion release and infectivity.

HEK 293T cells (0.8 × 106) were cultured in six-well plates and treated twice with 50 pmol siRNA against GFP (control), hVps18, hMon2, or Tsg101 with a 24-h interval by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). pNL4-3 (1 μg) was cotransfected with the second siRNA transfection. Forty-eight hours after the second siRNA transfection, the supernatants were collected and centrifuged through a 20% sucrose cushion and then analyzed by using Western blotting with an anti-p24 monoclonal antibody. Viral infectivity was determined by using a single-cell MAGIC assay, as described previously (19). In brief, CCR-5 expressing HeLa/CD4+ cells (MAGIC-5) (19) carrying the β-galactosidase gene under the control of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat were infected with HIV-1 that was released into the supernatants in triplicate in 24-well plates and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After 48 h, cells were fixed and those expressing β-galactosidase were detected by using a β-Gal staining kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The blue cells in each well were counted and normalized to the control.

Confocal microscopy.

HeLa cells were cultured on glass-bottomed dishes and transfected with pNL4-3 and FLAG-tagged hVps18 or a FLAG-tagged tsg101-expressing plasmid at a 1:1 DNA ratio. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, Lysotracker red dye (Invitrogen) was added at a concentration of 50 nM and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Flag-tagged proteins were visualized with a mouse anti-FLAG antibody as a primary antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen), and examined with a Zeiss LSM410 laser scanning microscope.

Electron microscopy.

Ultrathin-section electron microscopy was performed as described previously (35). Briefly, the plasmid-transfected cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and postfixed with 2% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer. They were then dehydrated with a series of ethanol gradients, followed by propylene oxide, before being embedded in an Epon 812 resin mixture (TAAB Laboratories Equipment Ltd., Berkshire, United Kingdom). Thin sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Raynold's lead and examined under a Hitachi H-7500 electron microscope at 80 kV.

RESULTS

Identification of host proteins required for HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane in yeast cells.

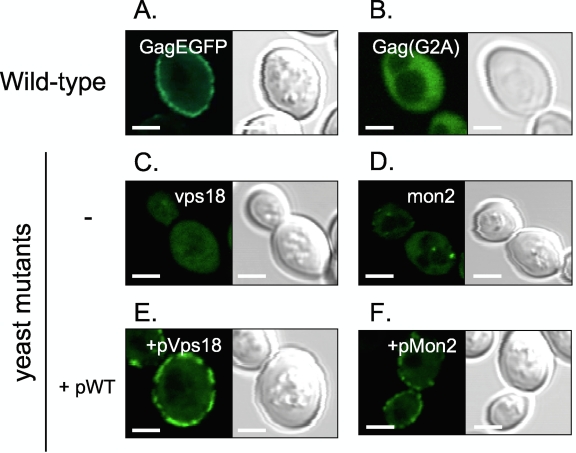

To identify cellular factors involved in HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane, we used yeast mutants that affect Gag localization. To this end, we first evaluated whether altered intracellular localization of the Gag protein in yeast cells can be visualized by fluorescence microscopy by examining a Gag mutant that lacked membrane targeting. Gag targeting to the plasma membrane was clearly seen in the yeast that expressed the wild-type GagEGFP fusion protein (Fig. 1A; 68% of the wild-type cells exhibited membrane accumulation of GagEGFP) but not (G2A)GagEGFP (Fig. 1B), which lacks membrane targeting activity due to the loss of a myristoylation signal (5, 17, 45). Correspondingly, Gag-induced, but not (G2A)Gag-induced, VLPs appeared in the culture supernatant, indicative of VLP release (Fig. 2). These results indicate that alteration of HIV-1 Gag localization in yeast cells can be visualized.

Fig. 1.

Effect of host proteins on the localization of the Gag protein and Gag-induced VLP production. (A to F) Fluorescence images (left panels) or DIC (differential interference contrast) (right panels) images of yeast expressing the GagEGFP (A, C to F) or Gag(G2A)EGFP (B) protein. For panels E and F, wild-type yeast Vps18 and yeast Mon2 protein-expressing plasmids were introduced, respectively. Size bars represent 2 μm.

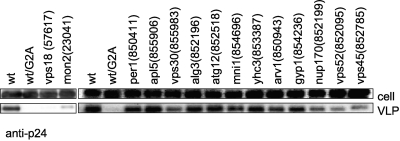

Fig. 2.

Gag VLP production in wild-type and mutant yeast cells. Wild-type and mutant strains were transformed with a Gag protein-expressing plasmid. As a negative control, a nonmyristoylated form of Gag was introduced into wild-type yeast by use of the Gag(G2A)-expressing plasmid (lanes labeled wt/G2A). Transformed cells were cultured, and cell walls were removed to prepare spheroplasts. Spheroplasts were cultured, and supernatant was collected, centrifuged through a 20% sucrose cushion, and analyzed by using Western blotting with an anti-p24 antibody. GeneID is shown in each box.

We then transformed a yeast single-gene deletion library containing 4,792 deletion strains with a plasmid expressing the GagEGFP fusion protein to identify cellular factors required for GagEGFP targeting to the plasma membrane. The transformed library was cultured and visually inspected by using fluorescence microscopy. Of the 4,792 mutant strains, 387 could not be analyzed because of their slow growth, inefficient transformation, or both. Of the remaining 4,405 mutant strains, 917 were aberrant for GagEGFP targeting to the plasma membrane; note that we included yeast strains in which GagEGFP localization was only slightly different from that of the wild type, since our criteria for differentiating normal from aberrant were subjective. Based on annotation in the Saccharomyces genome database (www.yeastgenome.org), we found that the functions of the genes deleted in 264 of the 917 yeast mutants were unknown, and those of 470 mutants were implicated in cell metabolism (e.g., DNA replication, transcription, or protein kinases). The genes deleted in the remaining 183 mutants were associated with protein trafficking, endocytosis, or the cytoskeleton. From these 183 mutants, we selected mutants whose deleted genes had single orthologous counterparts in humans, which left us with 14 mutant strains.

The Vps18 and Mon2 proteins are required for Gag-induced VLP release in yeast cells.

We then examined Gag VLP release in these 14 yeast mutants. We transformed wild-type yeast and the 14 mutant strains with a plasmid expressing the Gag protein and examined HIV-1 Gag-induced VLP release in the culture supernatant. Figure 2 shows that, of the 14 mutants, HIV-1 Gag-induced VLPs were appreciably reduced from the vps18 and mon2 mutant strains compared to levels in the wild type, indicating that the lack of the Vps18 and Mon2 proteins negatively affects Gag-induced VLP release in yeast cells. For the rest of the mutant strains, Gag-induced VLP release was similar to that of the wild-type yeast cells or was not reduced as substantially as that of the vps18 and mon2 mutant strains (Fig. 2).

To confirm that these two proteins were indeed responsible for correct HIV-1 Gag intracellular localization in yeast, we introduced the Vps18 and Mon2 genes back into the corresponding deletion mutant strains. In mutant cells exogenously expressing Vps18 or Mon2 protein, GagEGFP distribution was similar to that seen in the wild-type yeast cells (compare Fig. 1C and E and Fig. 1D and F). Membrane accumulation of GagEGFP was observed in 68%, 0%, 6%, 78%, and 80% of the wild type, vps18 deletion mutant, mon2 deletion mutant, vps18 deletion mutant expressing the Vps18 protein, and mon2 deletion mutant expressing the Mon2 protein, respectively (Fig. 1A to F). Therefore, we conclude that the yeast Vps18 and Mon2 proteins are required for GagEGFP trafficking to the plasma membrane in yeast cells.

Effects of mammalian Vps18 and Mon2 on Gag protein intracellular trafficking.

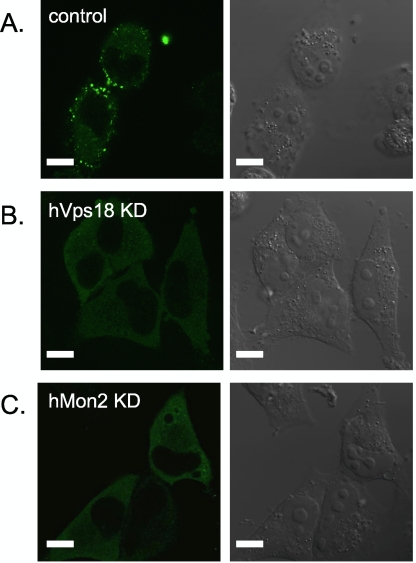

Vps18 and Mon2 are orthologues of human Vps18 (hVps18: GeneID 57617; 26% amino acid similarity) (25) and Mon2 (hMon2: GeneID 23041; 22% amino acid similarity) (10), respectively. The hVps18 (vacuolar protein sorting 18) protein is a component of the class C vacuolar protein sorting (VPS) complex, which is involved in the fusion and clustering of late endosomes/lysosomes (20, 25). The Mon2 gene, which was named after monensin, was originally identified in a yeast mutant known to be sensitive to the ionophore monensin (31). The Mon2 protein has a role in clathrin-dependent trafficking (14, 44). Based on our finding with the yeast vps18 and mon2 mutant strains that GagEGFP targeting to the plasma membrane was lost, we examined the effects of hVps18 and hMon2 depletion on Gag targeting to the plasma membrane in mammalian cells (Fig. 3). HeLa cells were pretreated with siRNA targeting hVps18 (Fig. 3B; hVps18KD) or hMon2 (Fig. 3C; hMon2KD), as well as with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 3A; control), 24 h prior to pNL4-3 transfection. Twenty-four hours posttransfection of the cells with pNL4-3, the intracellular distribution of Gag was analyzed by using confocal microscopy. Although Gag accumulated at the plasma membrane in the control cells (Fig. 3A), we did not detect Gag protein at the plasma membrane in hVps18- or hMon2-depleted cells (Fig. 3B and C). In agreement with our yeast vps18 and mon2 mutant results, we conclude that hVps18 and hMon2 are also required for proper Gag localization in mammalian cells.

Fig. 3.

Gag localization in human cells treated with siRNAs targeting hVps18 and hMon2. HeLa cells were pretreated with 100 pmol siRNA against a nontarget (A; control), hVps18 (B; hVps18KD), or hMon2 (C; hMon2KD), 24 h before pNL4-3 transfection. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then stained with an anti-p24 antibody and analyzed by using confocal microscopy. Left panels, fluorescence images. Right panels, differential interference contrast (DIC) images. Size bars represent 10 μm.

hVps18 and hMon2 are required for the efficient production of infectious HIV-1 virions in human cells.

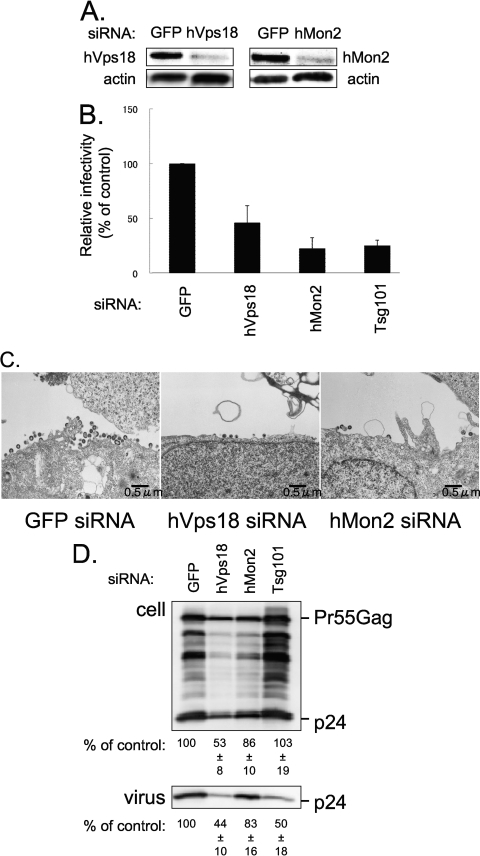

We next examined the effects of siRNA-mediated depletion of hVps18 and hMon2 on infectious HIV-1 virion production in human embryonic kidney 293T cells. In these experiments, an siRNA against Tsg101 (12) served as a positive control. Cells were treated twice at 24-h intervals with siRNAs against GFP (control), hVps18, hMon2, and Tsg101; the HIV-1 molecular clone pNL4-3 was cotransfected with the second siRNA transfection. As shown in Fig. 4A, the siRNAs against hVps18 and hMon2 reduced endogenous hVps18 and hMon2 expression, respectively. Forty-eight hours after the second transfection, supernatants were collected and assayed for viral infectivity. Compared to the control siRNA treatment, depletion of hVps18, hMon2, and Tsg101 reduced the number of HIV-1-infected cells (Fig. 4B), suggesting that hVps18 and hMon2 are important for efficient production of infectious HIV-1 particles.

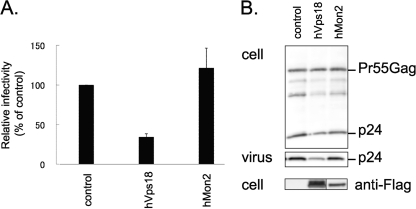

Fig. 4.

Depletion of hVps18 or hMon2 reduces HIV-1 virion release. (A and B) 293T cells were treated twice at 24-h intervals with siRNAs against GFP (control), hVps18, hMon2, or Tsg101. The HIV-1 molecular clone pNL4-3 was cotransfected at the second siRNA transfection. Forty-eight hours after the second siRNA transfection, the supernatants were collected for a viral infectivity assay. Depletion of endogenous hVps18 and hMon2 was evaluated with an antibody to each protein (A). Viral infectivity was assessed by use of the single-cycle MAGIC assay. The results presented here are representative of three independent experiments and are expressed as a percentage of the control (GFP siRNA) (B). (C) Ultrathin-section electron microscopy images. HeLa cells transfected with pNL4-3 and with the control GFP siRNA (left panel), the hVps18 siRNA (middle panel), or the hMon2 siRNA (right panel). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were fixed and processed for electron microscopy analysis. Size bars are represented in each panel. (D) Effect of siRNA against hVps18 or hMon2 on the amounts of HIV-1 proteins in cells and supernatants of cells transfected with an HIV-1 molecular clone. HeLa cells were transfected with the HIV-1 molecular clone pNL4-3 together with siRNAs targeting GFP, hVps18, hMon2, or Tsg101. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were collected and supernatant was pelleted through a 20% sucrose cushion. Cell lysates (upper panel) and supernatants subjected to ultracentrifugation through the 20% sucrose cushion (lower panel) were analyzed by using Western blotting with an anti-p24 antibody. For each siRNA, the levels of intracellular p24 and extracellular virions in the representative experiment are given as a percentage of the GFP siRNA control. The data represent averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments.

To determine whether the reduction in infectious virion production was due to reduced virion release, we examined virion release by using electron microscopy and Western blot analysis. Electron microscopy revealed that fewer virion particles were released from cells treated with siRNAs targeting hVps18 or hMon2 (Fig. 4C, middle or right panel, respectively) than from the control cells (Fig. 4C, left panel). Figure 4D shows that, in hVps18-depleted cells, the level of released HIV-1 virions was lower than that in the control GFP siRNA-treated cells (53% of control), although the level of Gag expression in the hVps18-depleted cells was also reduced (44% of control). In contrast, for hMon2, substantial amounts of extracellular p24 protein were detected in the culture supernatant of cells treated with the hMon2 siRNA (Fig. 4D) despite the reduction in virion particle release observed in hMon2-depleted cells (Fig. 4C, right panel). The reason for the discrepancy between the electron microscopy (Fig. 4C, right panel) and Western blot (Fig. 4D) findings is unclear. However, we speculate that our Western blot analysis may have detected pieces of cellular membrane that contained viral proteins from the culture supernatant of cells treated with the hMon2 siRNA.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the reduction in viral infectivity from cells treated with siRNAs against hVps18 or hMon2 originated from reduced infectious virion release.

Overexpression of hVps18 induces an aberrant acidic compartment and reduces virus particle release.

To further characterize the roles of hVps18 and hMon2 in HIV-1 particle formation, we examined the effect of overexpression of hVps18 and hMon2 (Fig. 5). 293T cells were transfected with pNL4-3 along with the control pCAGGS/MCS or N-terminal FLAG-tagged hVps18- or C-terminal FLAG-tagged hMon2-expressing plasmids. Forty-eight hours after transfection, viral infectivity in the supernatants was determined by using single-cycle MAGIC assays. As shown in Fig. 5A, hVps18, but not hMon2, overexpression inhibited virus release (∼30% of the control); these results were confirmed by using Western blotting with lysates and supernatants of cells transfected with pNL4-3 (Fig. 5B).

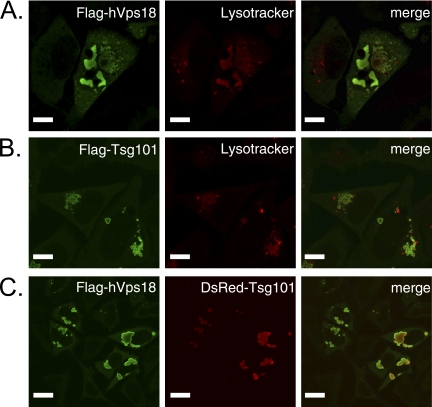

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of hVps18, but not hMon2, reduces HIV-1 production. 293T cells were cotransfected with pNL4-3 and a pCAGGS/MCS (control), an N-terminal FLAG-tagged hVps18, or a C-terminal FLAG-tagged hMon2 expression vector at a 1:1 DNA ratio. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, supernatants were collected for viral infectivity assays or centrifuged through a 20% sucrose cushion. (A) Single-round MAGIC assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented here are representative of three independent experiments and are expressed as a percentage of the control (pCAGGS/MCS). (B) Western blotting was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4D. Expression of the FLAG-tagged hVps18 or hMon2 proteins was detected by use of an anti-FLAG antibody.

To further examine the mechanism by which overexpression of hVps18 inhibits virus release, we analyzed the intracellular localization of hVps18 by using confocal microscopy. HeLa cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing N-terminal FLAG-tagged hVps18 and fixed 24 h posttransfection. As shown in Fig. 6A, hVps18 overexpression induced large, aberrant vesicular structures in the cytoplasm of cells (Fig. 6A, left panel). These structures stained with Lysotracker dye, which accumulates in acidic cellular compartments (Fig. 6A, merge). Tsg101 overexpression induces aberrant structures and disrupts retrovirus particle production (8, 16, 22), which we confirmed (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, hVps18 and DsRedTsg101 colocalized in cotransfected cells, indicating that the mechanism by which hVps18 overexpression reduces HIV-1 virion release is similar to that of Tsg101 overexpression; that is, virus release is inhibited via a negative effect on the cellular endosomal sorting machinery (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

hVps18 overexpression induces an aberrant acidic compartment. HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged hVps18 (upper panels), FLAG-tagged Tsg101 (middle panels), or FLAG-tagged hVps18 and DsRed-Tsg101 (lower panels)-expressing vectors at a 1:1 DNA ratio. Twenty-four hours after transfections, Lysotracker red dye was added to the FLAG-tagged hVps18 or FLAG-tagged Tsg101-expressing cells, and the samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C prior to fixation. The cells were then permeabilized and stained with an anti-FLAG antibody and analyzed by using confocal microscopy. Size bars represent 10 μm.

Interactions between the HIV-1 Gag protein and the hVps18 and hMon2 proteins.

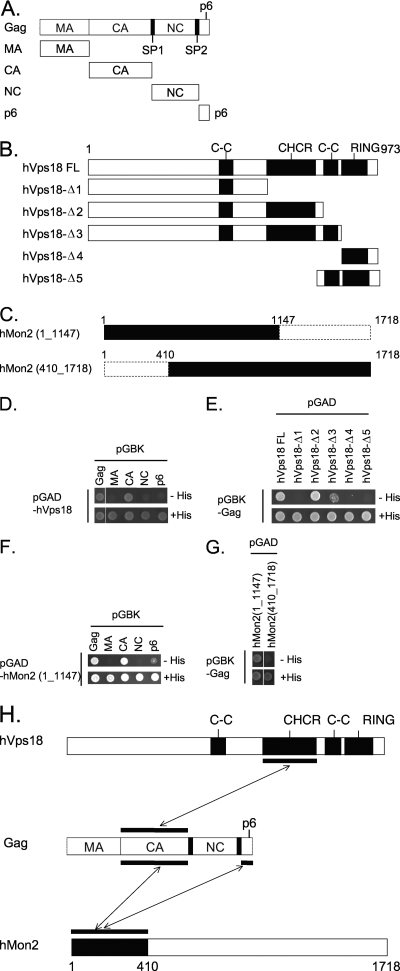

Next, we examined the interaction between the HIV-1 Gag protein and hVps18 or hMon2 in 293 cells. However, we were unable to detect any interactions between the proteins by using coimmunoprecipitation assays in human 293 cells. We therefore attempted to detect the interaction by using yeast two-hybrid assays. We generated several constructs of Gag (Fig. 7A), hVps18 (Fig. 7B), and hMon2 (Fig. 7C). First, we analyzed the interaction between hVps18 and Gag and found that full-length hVps18 interacted with full-length Gag (Fig. 7D, Gag). The capsid (CA) domain of Gag was required for the interaction with hVps18 (Fig. 7D, CA). Conversely, we found that the clathrin heavy-chain repeat (CHCR) domain of hVps18 was required for the interaction with Gag (Fig. 7E), suggesting that the interaction between the CA domain of Gag and the CHCR domain of hVps18 is important, as illustrated in Fig. 7H. For hMon2, we first used the full-length hMon2 construct to investigate its interaction with full-length Gag. Unfortunately, the growth of cells cotransformed with both constructs was very slow on histidine-deficient plates, whereas cells transformed with hMon2 with a C-terminal deletion and full-length Gag grew well (data not shown). Therefore, we used this C-terminal deletion hMon2 construct (hMon2_1-1147) to identify the interaction domain in the Gag protein. As shown in Fig. 7F, we found that the CA domain and the p6 domain (Fig. 7F, CA and p6) in the Gag protein interacted with the C-terminally deleted hMon2. Cells cotransformed with an N-terminally deleted hMon2 (hMon2_410-1718) and full-length Gag did not grow on histidine-deficient plates (Fig. 7G), suggesting that the N-terminal region (hMon2_1-410) is critical for the interaction with the Gag protein. Taken together, we conclude that the N-terminal region of hMon2 is essential for its interaction with the CA and p6 domains of Gag, as illustrated in Fig. 7H.

Fig. 7.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis of the Gag and hVps18 or hMon2 interaction. (A) Schematic representation of HIV-1 Gag protein. Open boxes indicate the matrix (MA) domain, capsid (CA) domain, nucleocapsid (NC) domain, and p6 domain, respectively. Solid boxes indicate the small spacer regions between the CA and NC domains (SP1) or the NC and p6 domains (SP2). (B) Schematic representation of hVps18 deletion constructs. C-C, coiled-coil; CHCR, clathrin heavy-chain repeat; RING, RING-H2 finger. (C) Schematic representation of hMon2 deletion constructs. (D and E) Mapping studies of the hVps18 and Gag binding domain. Yeast cells were cotransformed with plasmids encoding the GAL4 activation domain (pGAD) fused to hVps18 or the hVps18 deletion construct (shown in panel B) and the GAL4-binding domain (pGBK) fused to full-length Gag (Gag) or one of the Gag domains (MA, CA, NC, p6). Cotransformed cells were spotted onto histidine-deficient (−His) or histidine-containing (+His) plates and incubated at 30°C for 2 to 3 days. Growth on histidine-deficient (−His) plates is indicative of an interaction between the two proteins. (F and G) Mapping studies of the hMon2- and Gag-binding domains. hMon2 deletion constructs expressed in yeast were analyzed for their interaction with the Gag protein as described in the legend to panels D and E. (H) Interactions between the Gag protein and hVps18 or hMon2.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a yeast single-gene deletion library to identify novel cellular factors that are required for efficient HIV-1 virion assembly. The yeast vps18 and mon2 mutant strains were deficient in GagEGFP targeting to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1C and D), a phenotype that was complemented by the expression of the Vps18 or Mon2 protein, indicating their requirement for the trafficking of GagEGFP to the plasma membrane in yeast (Fig. 1E and F). Further, Gag-induced VLP release from the vps18 and mon2 mutant strains was reduced drastically compared to that from the wild-type yeast strain. In agreement with this result, in human cells, we found that Gag accumulation at the plasma membrane and HIV-1 virion production were inhibited in hVps18- or hMon2-depleted cells (Fig. 3 and 4). These observations suggest that hVps18 and hMon2 are novel cellular factors involved in HIV-1 virion production.

hVps18 is a component of the class C VPS complex, which is formed with hVps11, hVps16, and hVps33, and regulates LE/lysosome membrane clustering and fusion (26, 38), which regulates multiple cellular physiological processes (33). In addition, hVps18 exhibits E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro (53, 54). Since ubiquitination of the Gag protein is important for the late steps of HIV-1 replication (37, 43, 46), hVps18 may function as an E3 ubiquitin ligase in this process. Furthermore, our electron microscopic analysis revealed that the core of the HIV-1 virions released from the 293T cells treated with hVps18 siRNA was “round” and “acentric,” which differs from the normal “cone-shaped” core structure (unpublished data). Since proper viral core assembly is important for viral infectivity (11, 40, 47), depletion of the hVps18 protein may cause aberrant core assembly, leading to a reduction in infectious HIV-1 particle production.

Here, we showed that overexpression of hVps18 blocks HIV-1 particle release and induces an aberrant acidic compartment similar to that induced by Tsg101 overexpression (Fig. 5 and see reference 16). Several studies suggest that overexpression of full-length or dominant negative forms of the proteins that make up ESCRT complexes, and their associated machinery, results in the formation of aberrant compartments (16, 23, 24), called class E-type compartments. The mechanistic basis for the inhibitory effects of Tsg101 overexpression on HIV-1 particle release is unknown; however, these aberrant structures likely affect cellular trafficking globally and, thereby, impair HIV-1 virion release.

Multimeric Mon2 is involved in vesicle formation and endosome biogenesis at the tubular endosomal network/trans-Golgi network (TEN/TGN) in yeast cells (10, 44). One of the hMon2-interacting partners, GGA (Golgi-localized gamma-ear containing Arf-binding) protein, is a monomeric clathrin adaptor protein, which participates in vesicle budding at the TEN/TGN (44). Interestingly, GGA is also involved in retrovirus assembly and release (23, 24). Therefore, it is highly likely that hMon2 contributes to retrovirus assembly and release. For HIV-1, the Gag MA domain binds to the clathrin adaptor complexes AP-1 and AP-3. Knockdown of AP-1 and AP-3 expression reduces virion assembly (6, 9), suggesting their involvement in HIV-1 virion assembly. Interestingly, hMon2 depletion alters AP-1 and AP-3 intracellular localization (44) and reduces transferrin internalization, which is mediated by endocytosis. Therefore, it may be that hMon2 facilitates HIV-1 particle formation by its association with AP-1 or AP-3 or both.

The recent development of genomic analytical tools, such as siRNA libraries, DNA microarrays, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems, has allowed the identification of several cellular factors involved in HIV-1 replication (15). Interestingly, in these screening systems, well-characterized cellular factors (e.g., Tsg101) that function in the late stage of the viral life cycle were not identified (4, 28, 55). Here, we demonstrate that yeast genetic screening is useful for identifying novel cellular factors involved in the late stage of the viral replication cycle.

Recently, antiviral drugs that target late steps in viral replication have been developed (e.g., PA457 for HIV-1 and neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza virus). Viral diseases, including AIDS and influenza, continue to pose public health concerns, while drug-resistant viruses complicate efforts to minimize outbreaks. For this reason, novel antiviral compounds are needed. Since we have shown here that hVps18 or hMon2 depletion reduces HIV and influenza VLP release and several viral proteins use components of ESCRT complexes for their budding, viral-host protein interactions during the late stages of the viral life cycle may make suitable targets for drug development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Fumitaka Momose and Hiyori Haraguchi (Kitasato University, Tokyo) for helpful discussions. We also thank Susan Watson for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, by Grants-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research and for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, by ERATO (Japan Science and Technology Agency), and by Public Health Service research grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adachi A., et al. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bailer S. M., Haas J. 2009. Connecting viral with cellular interactomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:453–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bieniasz P. D. 2009. The cell biology of HIV-1 virion genesis. Cell Host Microbe 5:550–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brass A. L., et al. 2008. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science 319:921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryant M., Ratner L. 1990. Myristoylation-dependent replication and assembly of human immunodeficiency virus 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camus G., et al. 2007. The clathrin adaptor complex AP-1 binds HIV-1 and MLV Gag and facilitates their budding. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:3193–3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chung H. Y., et al. 2008. NEDD4L overexpression rescues the release and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 constructs lacking PTAP and YPXL late domains. J. Virol. 82:4884–4897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Demirov D. G., Ono A., Orenstein J. M., Freed E. O. 2002. Overexpression of the N-terminal domain of TSG101 inhibits HIV-1 budding by blocking late domain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:955–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dong X., et al. 2005. AP-3 directs the intracellular trafficking of HIV-1 Gag and plays a key role in particle assembly. Cell 120:663–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Efe J. A., et al. 2005. Yeast Mon2p is a highly conserved protein that functions in the cytoplasm-to-vacuole transport pathway and is required for Golgi homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 118:4751–4764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fitzon T., et al. 2000. Proline residues in the HIV-1 NH2-terminal capsid domain: structure determinants for proper core assembly and subsequent steps of early replication. Virology 268:294–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garrus J. E., et al. 2001. Tsg101 and vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gietz R. D., Sugino A. 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74:527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gillingham A. K., Whyte J. R., Panic B., Munro S. 2006. Mon2, a relative of large Arf exchange factors, recruits Dop1 to the Golgi apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 281:2273–2280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goff S. P. 2008. Knockdown screens to knockout HIV-1. Cell 135:417–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goila-Gaur R., Demirov D. G., Orenstein J. M., Ono A., Freed E. O. 2003. Defects in human immunodeficiency virus budding and endosomal sorting induced by TSG101 overexpression. J. Virol. 77:6507–6519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gottlinger H. G., Sodroski J. G., Haseltine W. A. 1989. Role of capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5781–5785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reference deleted.

- 19. Hachiya A., et al. 2001. Rapid and simple phenotypic assay for drug susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 using CCR5-expressing HeLa/CD4+ cell clone 1-10 (MAGIC-5). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:495–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huizing M., et al. 2001. Molecular cloning and characterization of human VPS18, VPS11, VPS16, and VPS33. Gene 264:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janda M., Ahlquist P. 1993. RNA-dependent replication, transcription, and persistence of brome mosaic virus RNA replicons in S. cerevisiae. Cell 72:961–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson M. C., Spidel J. L., Ako-Adjei D., Wills J. W., Vogt V. M. 2005. The C-terminal half of TSG101 blocks Rous sarcoma virus budding and sequesters Gag into unique nonendosomal structures. J. Virol. 79:3775–3786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joshi A., Garg H., Nagashima K., Bonifacino J. S., Freed E. O. 2008. GGA and Arf proteins modulate retrovirus assembly and release. Mol. Cell 30:227–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joshi A., Nagashima K., Freed E. O. 2009. Defects in cellular sorting and retroviral assembly induced by GGA overexpression. BMC Cell Biol. 10:72–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim B. Y., et al. 2001. Molecular characterization of mammalian homologues of class C Vps proteins that interacts with syntaxin-7. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29393–29402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim B. Y., et al. 2003. Identification of mouse Vps16 and biochemical characterization of mammalian class C Vps complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311:577–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kobasa D., Rodgers M. E., Wells K., Kawaoka Y. 1997. Neuraminidase hemadsorption activity, conserved in avian influenza A viruses, does not influence viral replication in ducks. J. Virol. 71:6706–6713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. König R., et al. 2008. Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell 135:49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kushner D. B., et al. 2003. Systematic, genome-wide identification of host genes affecting replication of a positive-strand RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:15764–15769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morita E., Sundquist W. I. 2004. Retrovirus budding. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:395–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muren E., Oyen M., Barmark G., Ronne H. 2001. Identification of yeast deletion strains that are hypersensitive to brefeldin A or monensin, two drugs that affect intracellular transport. Yeast 18:163–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naito T., et al. 2007. An influenza virus replicon system in yeast identified Tat-SF1 as a stimulatory host factor for viral RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:18235–18240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nickerson D. P., Brett C. L., Merz A. J. 2009. Vps-C complexes: gate keepers of endolysosomal traffic. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21:543–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Noda T., et al. 2002. Ebola virus VP40 drives the formation of virus-like filamentous particles along with GP. J. Virol. 76:4855–4865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Panavas T., Serviene E., Pogany J., Nagy P. D. 2008. Genome-wide screens for identification of host factors in viral replication. Methods Mol. Biol. 451:615–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patnaik A., Chau V., Wills J. W. 2000. Ubiquitin is part of the retrovirus budding machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13069–13074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peterson M. R., Emr S. D. 2001. The class C Vps complex functions at multiple stages of the vacuolar transport pathway. Traffic 2:476–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Price B. D., Rueckert R. R., Ahlquist P. 1996. Complete replication of an animal virus and maintenance of expression vectors derived from it in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:9465–9470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reicin A. S., Ohagen A., Yin L., Hoglund S., Goff S. P. 1996. The role of Gag in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion morphogenesis and early steps of the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 70:8645–8652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sakuragi S., Goto H., Sano K., Morikawa Y. 2002. HIV type 1 Gag virus-like particle budding from spheroplasts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7956–7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scarlata S., Carter C. 2003. Role of HIV-1 Gag domains in viral assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1614:62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schubert U., et al. 2000. Proteasome inhibition interferes with gag polyprotein processing, release, and maturation of HIV-1 and HIV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13057–13062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Singer-Kruger B., et al. 2008. Yeast and human Ysl2p/hMon2 interact with Gga adaptors and mediate their subcellular distribution. EMBO J. 27:1423–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Spearman P., Wang J. J., Vander Heyden N., Ratner L. 1994. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein domains essential to membrane binding and particle assembly. J. Virol. 68:3232–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Strack B., Calistri A., Accola M. A., Paul G., Gottlinger H. G. 2000. A role for ubiquitin ligase recruitment in retrovirus release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13063–13068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang S., et al. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 N-terminal capsid mutants that exhibit aberrant core morphology and are blocked in initiation of reverse transcription in infected cells. J. Virol. 75:9357–9366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y., Ishige M., Murakami M. 2007. Oral attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine expressing codon-optimized HIV type 1 gag enhanced intestinal immunity in mice. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 23:278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y., et al. 2003. Yeast-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p55(gag) virus-like particles activate dendritic cells (DCs) and induce perforin expression in Gag-specific CD8+ T cells by cross-presentation of DCs. J. Virol. 77:10250–10259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Usami Y., Popov S., Gottlinger H. G. 2007. Potent rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 late domain mutants by ALIX/AIP1 depends on its CHMP4 binding site. J. Virol. 81:6614–6622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Usami Y., Popov S., Popova E., Gottlinger H. G. 2008. Efficient and specific rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 budding defects by a Nedd4-like ubiquitin ligase. J. Virol. 82:4898–4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Winzeler E. A., et al. 1999. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285:901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yogosawa S., et al. 2005. Ubiquitylation and degradation of serum-inducible kinase by hVPS18, a RING-H2 type ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:41619–41627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yogosawa S., et al. 2006. Monoubiquitylation of GGA3 by hVPS18 regulates its ubiquitin-binding ability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350:82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhou H., et al. 2008. Genome-scale RNAi screen for host factors required for HIV replication. Cell Host Microbe 4:495–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]