Abstract

The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) ORF94 gene product has been reported to be expressed during both productive and latent phases of infection, although its function is unknown. We report that expression of pORF94 leads to decreased 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) expression in transfected cells with and without interferon stimulation. Furthermore, the functional activity of OAS was inhibited by pORF94. Finally, we present evidence of OAS modulation by pORF94 during productive HCMV infection of human fibroblasts. This study provides the first identification of a function for pORF94 and identifies an additional means by which HCMV may limit a critical host cell antiviral response.

TEXT

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infects a majority of the world's population and causes significant morbidity and mortality in neonates and in immunosuppressed individuals, such as solid organ and allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients and those with HIV AIDS (22). The capacity of HCMV to infect a large proportion of the population is presumed to be aided by expression of viral genes with immunoevasive functions. In this respect, a number of viral genes which function to evade multiple arms of the host immune defense systems have been identified (23). HCMV also establishes a life-long latent infection in which infectious virus is not detectable and viral gene expression is highly restricted (27). Even during latency, viral gene expression which limits immune recognition of infected cells has been identified (6, 12). Thus, virally encoded immune evasion appears to be a feature of both productive and latent phases of infection.

Earlier studies using an experimental model of latent infection and granulocyte macrophage progenitor cells (GM-Ps) identified transcription from the HCMV major immediate early (MIE) region. These MIE region cytomegalovirus latency-associated transcripts (CLTs) arose from both sense and antisense strands (10, 14, 15, 28). Although MIE region CLTs have not been universally detected during latency (3), sense CLTs have been shown to be expressed during productive infection (18, 29). Additionally, antibodies to open reading frames (ORFs) encoded by MIE region CLTs have been detected in HCMV-seropositive individuals, indicating that the products of these ORFs are expressed at some point during natural HCMV infection (15, 17). This includes ORF94, the largest of the ORFs encoded by sense CLTs (15). To date, a function for ORF94 has not been identified, as an ORF94 start codon point mutant virus replicated normally in primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) and was not impaired in its capacity to establish and reactivate from latency (29). A clue to the function of pORF94 stemmed from the observation that it is nuclearly localized, suggesting a potential role in cellular gene regulation (29).

The 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS)/RNase L pathway is an important innate immune response which acts to block viral infections. In humans, the OAS family of enzymes is encoded by three functional genes: OAS1 to OAS3 (13). OAS proteins are produced as latent enzymes which become activated following binding to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). Activated OAS oligomerizes ATP into 2′,5′-linked oligoadenylate products (2-5A) (2, 8), which activate latent endoribonuclease L, RNase L, resulting in the degradation of viral and cellular RNA and inhibition of virus replication (25). In addition, extracellular OAS proteins can enter cells and exert antiviral activity which is independent of RNase L, demonstrating that OAS can also act directly as an antiviral protein (16). OAS is expressed constitutively but is induced by both type I and type II interferon (IFN) (13). In this study, we sought to determine the impact of HCMV pORF94 on OAS expression and function.

HCMV pORF94 inhibits constitutive expression of OAS1 in transfected cells.

To determine whether pORF94 alters OAS expression, we measured OAS1 mRNA in HeLa cells transfected with a construct expressing pORF94 fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (pON2705 or ORF94-GFP) (29) or its parental construct, which expresses GFP but which lacks ORF94 cDNA (pON2701 or parent GFP) (29). HeLa cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Switzerland) with either the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP expression vector for 72 h before being sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (BD FACSVantage SE cell sorter; BD Biosciences) for the GFP-positive population of cells (representing positive transfectants). Sorting of GFP-positive cells ensured that analysis of OAS1 mRNA was restricted to positive transfectants that either did or did not express pORF94.

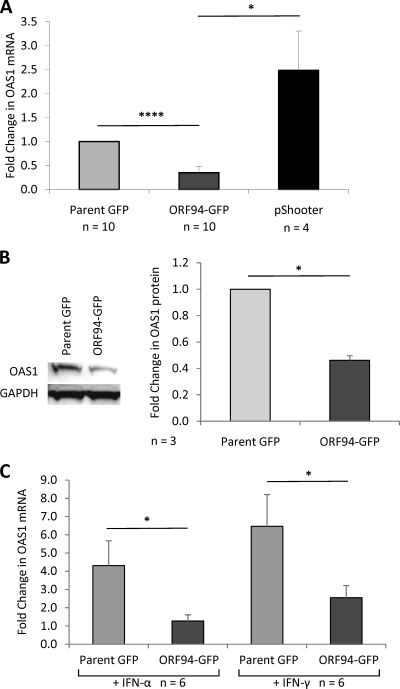

The relative amount of OAS1 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Mx3000P qPCR system; Stratagene) with cycling parameters being 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 45 s, and finally 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 30 s, and 95°C for 30 s. Data were normalized in pairwise comparisons with each of three housekeeping genes, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β-actin, and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), and then averaged. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The data from at least three technical replicates were averaged and normalized to the value for the parent GFP sample to represent the fold change in mRNA expression. Ten independent biological replicate experiments were performed, and the change in OAS1 mRNA expression in cells transfected with the ORF94-GFP vector from that in cells transfected with the parent GFP vector was determined. This analysis revealed a statistically significant decrease in OAS1 mRNA expression in cells transfected with the ORF94-GFP vector (Fig. 1A). A pairwise comparison of the levels of mRNA expression of each housekeeping gene against every other housekeeping gene and of each housekeeping gene against OAS1 confirmed the robustness of this approach to define changes in OAS1 mRNA expression (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig. 1.

pORF94 inhibits expression of OAS1. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with the parent GFP, ORF94-GFP, or pShooter expression vector for 72 h before qRT-PCR for OAS1. mRNA levels were normalized to three host housekeeping genes and are shown relative to mRNA levels in cells transfected with the parent GFP vector. (B) Analysis of OAS1 protein expression by Western blotting of lysates from three independent experiments of HeLa cells transfected with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP expression vector. The relative amount of OAS1 protein was determined after densitometry results were normalized to the expression of GAPDH, used as a protein loading control. (C) Analysis of OAS1 mRNA expression by qRT-PCR in HeLa cells transfected with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP expression vector before treatment with either IFN-α (100 U/ml) or IFN-γ (100 U/ml) to induce OAS1. Data were normalized to three housekeeping genes and are expressed relative to OAS1 mRNA expression in cells transfected with the parent GFP vector without IFN treatment. The number of independent replicate experiments (n) is shown. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Significant differences were determined using a 1-tailed, paired Student t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P value < 0.05; ****, P value < 0.00005).

As pORF94 is a nuclearly localized protein, the GFP expressed by the ORF94-GFP vector is also targeted to the nucleus. Thus, to confirm that the decreased OAS1 mRNA expression in ORF94-GFP-transfected cells was not due to nuclear GFP, a nuclearly localized GFP expression vector (pShooter; Invitrogen) was included as an additional control in transfection and FACS experiments. In four independent replicate experiments, pORF94 significantly inhibited OAS1 mRNA expression, whereas nuclearly localized GFP delivered by transfection with the pShooter vector did not (Fig. 1A). These results demonstrated that inhibition of OAS1 mRNA was a consequence of pORF94 and not of nuclearly localized GFP.

To determine whether the observed pORF94-mediated decrease in OAS1 mRNA expression was detectable at the level of OAS1 protein expression, lysates of cells transfected with either the ORF94-GFP or parent-GFP vector (sorted by FACS for GFP expression) were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-OAS1 antibody (Thermo Scientific). The results of densitometry analysis of three independent experiments were normalized to results of probing with an anti-GAPDH antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as a loading control. This analysis revealed a decrease in OAS1 protein in the presence of pORF94 (Fig. 1B). Together with the mRNA analyses, these experiments demonstrated that pORF94 inhibited both OAS1 mRNA and protein expression.

HCMV pORF94 inhibits IFN-induced expression of OAS1 mRNA in transfected cells.

To determine whether pORF94 had an impact on IFN production, IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (PBL Interferon Source) in supernatants from HeLa cells 72 h after transfection with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP vector. Duplicates of standards of IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ were included as positive controls. Irrespective of whether cells were transfected with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP vector, IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ remained undetectable, indicating no measurable difference between these two vectors with respect to expression of these IFNs (data not shown).

We next determined whether pORF94 inhibited the IFN-mediated induction of OAS1. HeLa cells were transfected with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP vector for 48 h and then treated with 100 U/ml of IFN-α (Biosource International Inc.) or IFN-γ (Roche, Switzerland) for 24 h before FACS analysis for GFP-positive transfectants. Both IFN-α and IFN-γ induced OAS1 mRNA in cells transfected with the parent GFP vector; however, this induction of OAS1 was significantly inhibited in cells transfected with the ORF94-GFP vector (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that pORF94 modulates OAS1 expression in mammalian cells, with or without IFN stimulation.

HCMV pORF94 inhibits the functionality of OAS.

Activated OAS results in the synthesis of 2′,5′-linked oligoadenylate products (2-5A) which activate RNase L to cause RNA degradation (25). To determine if inhibition of OAS1 by pORF94 resulted in reduced OAS function, we measured the production of 2-5A using an OAS functional assay (24). HeLa cells transfected for 72 h with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP vector were sorted for GFP-positive cells to ensure that subsequent analyses were restricted only to positive transfectants that either did (ORF94-GFP vector) or did not (parent GFP vector) express ORF94. Protein extracts from these GFP-positive cells were incubated with poly(I) · poly(C) (GE Healthcare, United Kingdom) to activate latent OAS and with 32P-labeled ATP (Perkin Elmer), which served as a substrate for the synthesis of 2-5A. Reaction mixtures were separated by thin-layer chromatography and the resulting 2-5A visualized by autoradiography.

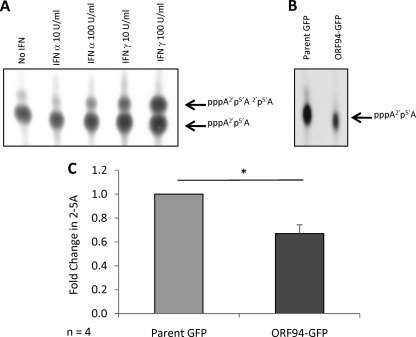

Positive controls were HeLa cells with no IFN, IFN-α (Biosource International Inc.), or IFN-γ (Roche, Switzerland) (Fig. 2A). HeLa cells with no IFN treatment showed that both OAS-driven incorporation of radiolabeled ATP into oligomerized 2-5A products that were predominantly dimers (pppA2′p5′A) and IFN-α or IFN-γ increased the amount of 2-5A. There were no detectable 2-5A when water or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (rather than protein extract) was incubated with 32P-labeled ATP (data not shown). Cell lysates from HeLa cells transfected with the ORF94-GFP vector yielded fewer 2-5A than lysates from HeLa cells transfected with the parent GFP vector (Fig. 2B). Densitometry analysis was performed, and intensities were normalized to those of the parent GFP-transfected cells from four independent replicate experiments (Fig. 2C). This analysis revealed a significant decrease in the generation of 2-5A from cells transfected with the ORF94-GFP vector. Taken together, these results demonstrate that HCMV pORF94 inhibits OAS1 expression, with the consequence of a decreased capacity to catalyze the formation of 2-5A.

Fig. 2.

Impact of pORF94 on the functionality of OAS. The capacity of OAS to catalyze the formation of 2-5A products was assessed using an OAS functional assay (24), with products visualized by thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography. (A) Positive controls consisting of cell lysates from HeLa cells without any IFN treatment (No IFN) or following treatment with either 10 U/ml or 100 U/ml of IFN-α or IFN-γ. Arrows indicate 2-5A products incorporating radiolabeled ATP as a dimer (pppA2′p5′A) or a trimer (pppA2′p5′A2′p5′A). (B) The formation of 2-5A products from cell lysates of HeLa cells transfected with the parent GFP or ORF94-GFP vector is shown. (C) Densitometry analysis of 2-5A from parent GFP- and ORF94-GFP-transfected cells from 4 independent replicate experiments. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. A significant difference from the parent GFP-transfected control was determined using a 1-tailed, paired Student t test and is denoted by an asterisk (P value < 0.05).

pORF94 modulates OAS1 during productive infection of human fibroblasts.

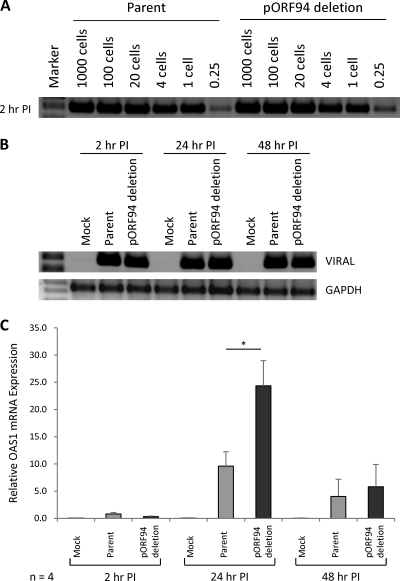

In addition to during latency (10, 14, 15, 28), the transcript encoding pORF94 is expressed in productively infected HFFs from as early as 2 h postinfection (18, 29). To determine whether pORF94 regulates OAS1 during productive infection, HFFs were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 with either a recombinant virus (RC2710) unable to express pORF94 due to the introduction of a point mutation that destroyed the only methionine codon available to translate this ORF or its parental Towne virus construct (RC303) (29).

PCR with the HCMV-specific primers IEP3C and IEP4BII (14) using DNA from cells at 2 h, 24 h, and 48 h postinfection (Fig. 3A and B) confirmed our earlier analysis of the kinetics of infection which showed that the ORF94 mutant virus infected and replicated in HFFs as efficiently as parental virus (29). At these times, RNA from four independent replicate experiments (using multiple independent virus stocks) was analyzed by qRT-PCR for OAS1 mRNA. Infection with either the parent or ORF94 mutant virus induced OAS1, unlike with mock-infected HFFs, and this induction was greatest at 24 h postinfection. Importantly, at this time point, infection with the ORF94 mutant virus resulted in a significantly higher induction of OAS1 than occurred in parent virus-infected counterparts. Thus, in the context of productive HCMV infection, pORF94 suppressed OAS1 expression.

Fig. 3.

Impact of pORF94 on OAS1 expression during productive infection of human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs). PCR amplification of viral DNA using primers IEP3C and IEP4BII (14) showing comparable levels of infection of HFFs with parental and ORF94 mutant viruses using cell lysate dilutions from 1,000 to 0.25 cell equivalent at 2 h postinfection (PI) (A) and cell lysates at 2 h, 24 h, and 48 h postinfection (B). The results of PCR for cellular GAPDH as a DNA loading control are also shown. (C) qRT-PCR for OAS1 mRNA expression in HFFs either mock infected or infected with the parental or ORF94 mutant virus at 2 h, 24 h, and 48 h postinfection. OAS1 expression is shown relative to that after mock infection. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. The number of independent replicate experiments (n) is shown. Significant differences between parental and ORF94 mutant viruses were determined using a 1-tailed, paired Student t test and are denoted by an asterisk (P value < 0.05).

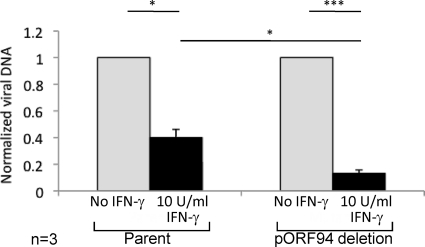

We also sought to determine whether the ORF94 mutant virus was more sensitive to the antiviral effects of IFN than the parent virus. HFFs were infected with the parent or ORF94 mutant virus (MOI = 3), and at 4 h postinfection, the culture medium was supplemented with 10 U/ml IFN-γ or left untreated. Assessment of the virus inoculum by plaque assay at the time of infection confirmed that equal amounts of the infectious parent and ORF94 mutant viruses were used for each infection (data not shown). At 72 h postinfection, cells from three independent replicate experiments were harvested and washed, and the viral DNA from lysed cells was assessed by qPCR using the HCMV-specific primers IEP3A and IEP3B (14). Relative changes in the amounts of viral DNA were determined by normalizing values to those for the cellular reference gene BCMA using published primers (9). In comparison to infected cells without the addition of IFN-γ, infected cells treated at 4 h postinfection with 10 U/ml IFN-γ significantly inhibited the DNA replication of both the parental and ORF94 mutant viruses (Fig. 4). However, the ORF94 mutant virus was more sensitive to the antiviral effects of IFN-γ than the parental virus (Fig. 4), indicating that pORF94 could partially counteract the IFN-γ-mediated antiviral response.

Fig. 4.

Impact of pORF94 on the antiviral effects of IFN during productive infection of HFFs. Viral DNA levels in HFFs treated with 10 U/ml IFN-γ or left untreated on day 3 postinfection with the parental or ORF94 mutant virus. Values determined by qPCR were normalized to the cellular gene BCMA and are shown relative to infection without the addition of IFN-γ. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. The number of independent replicate experiments (n) is shown. Significant differences were determined using a 1-tailed, paired Student t test and are denoted by asterisks (*, P value < 0.05; ***, P value < 0.0005).

It has been reported that HCMV inhibits IFN-α-stimulated OAS mRNA expression in human fibroblasts and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (21). However, others have reported that HCMV infection of fibroblasts induces OAS transcription (1, 4, 5, 26, 30, 31), which is consistent with our finding of increased OAS1 mRNA during productive HCMV infection. Two related HCMV genes, TRS1 and IRS2, which are expressed as immediate early genes, have been shown to counteract OAS/RNase L and protein kinase R (PKR) antiviral response pathways (7, 20). dsRNA, which accumulates in HCMV-infected cells (4, 19, 30), is bound by pTRS1 through a domain that is conserved in pIRS1, and it has been reported that this binding capability is important for pTRS1 and pIRS1 function (11). This may explain the requirement for pTRS1 and pIRS1 for HCMV replication (19). Our finding reveals that pORF94 inhibits OAS expression and function, identifying an additional viral gene product and mechanism that may provide an advantage to the virus during productive infection by limiting the induction of the OAS-mediated antiviral response. This conclusion is supported by our finding that the ORF94 mutant virus was more sensitive to the antiviral effects of IFN-γ than the parental virus. Whether pORF94 is able to inhibit OAS in latently infected cells remains to be determined. Reports that MIE region CLTs which encode pORF94 are either undetectable (3) or detectable in only 2 to 5% of experimentally latently infected GM-Ps (14, 28) will complicate these studies, but the potential for pORF94 to function in an immunoevasive capacity during both productive and latent phases of infection warrants further investigation, and this will be a focus of future studies to fully delineate the role(s) of this viral gene product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ricardo Sànchez and Ian Mohr for valuable advice on the OAS functional assay, Steven Schibeci for assistance with thin-layer chromatography, and Sanda Lum and Maggie Wang for assistance with FACS.

J.C.G.T. was the recipient of a Westmead Medical Research Foundation Initiating Grant. J.Z.C. was the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award and a Westmead Medical Research Foundation Stipend Enhancement Award. This work was supported by the Australian NHMRC Project and Program Grants awarded to B.S.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 30 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abate D. A., Watanabe S., Mocarski E. S. 2004. Major human cytomegalovirus structural protein pp65 (ppUL83) prevents interferon response factor 3 activation in the interferon response. J. Virol. 78:10995–11006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baglioni C., Minks M. A., Maroney P. A. 1978. Interferon action may be mediated by activation of a nuclease by pppA2′p5′A2′p5′A. Nature 273:684–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bego M., Maciejewski J., Khaiboullina S., Pari G., St. Jeor S. 2005. Characterization of an antisense transcript spanning the UL81-82 locus of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 79:11022–11034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyle K. A., Pietropaolo R. L., Compton T. 1999. Engagement of the cellular receptor for glycoprotein B of human cytomegalovirus activates the interferon-responsive pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3607–3613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Browne E. P., Shenk T. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus UL83-coded pp65 virion protein inhibits antiviral gene expression in infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:11439–11444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheung A. K., et al. 2009. The role of the human cytomegalovirus UL111A gene in down-regulating CD4+ T-cell recognition of latently infected cells: implications for virus elimination during latency. Blood 114:4128–4137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Child S. J., Hakki M., De Niro K. L., Geballe A. P. 2004. Evasion of cellular antiviral responses by human cytomegalovirus TRS1 and IRS1. J. Virol. 78:197–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clemens M. J., Williams B. R. 1978. Inhibition of cell-free protein synthesis by pppA2′p5′A2′p5′A: a novel oligonucleotide synthesized by interferon-treated L cell extracts. Cell 13:565–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Preter K., et al. 2002. Quantification of MYCN, DDX1, and NAG gene copy number in neuroblastoma using a real-time quantitative PCR assay. Mod. Pathol. 15:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hahn G., Jores R., Mocarski E. S. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3937–3942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hakki M., Geballe A. P. 2005. Double-stranded RNA binding by human cytomegalovirus pTRS1. J. Virol. 79:7311–7318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenkins C., Abendroth A., Slobedman B. 2004. A novel viral transcript with homology to human interleukin-10 is expressed during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 78:1440–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Justesen J., Hartmann R., Kjeldgaard N. O. 2000. Gene structure and function of the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase family. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57:1593–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kondo K., Kaneshima H., Mocarski E. S. 1994. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:11879–11883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kondo K., Xu J., Mocarski E. S. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus latent gene expression in granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in culture and in seropositive individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:11137–11142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kristiansen H., et al. 2010. Extracellular 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase stimulates RNase L-independent antiviral activity: a novel mechanism of virus-induced innate immunity. J. Virol. 84:11898–11904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landini M. P., Lazzarotto T., Xu J., Geballe A. P., Mocarski E. S. 2000. Humoral immune response to proteins of human cytomegalovirus latency-associated transcripts. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 6:100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lunetta J. M., Wiedeman J. A. 2000. Latency-associated sense transcripts are expressed during in vitro human cytomegalovirus productive infection. Virology 278:467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marshall E. E., Bierle C. J., Brune W., Geballe A. P. 2009. Essential role for either TRS1 or IRS1 in human cytomegalovirus replication. J. Virol. 83:4112–4120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marshall E. E., Geballe A. P. 2009. Multifaceted evasion of the interferon response by cytomegalovirus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:609–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller D. M., Zhang Y., Rahill B. M., Waldman W. J., Sedmak D. D. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits IFN-alpha-stimulated antiviral and immunoregulatory responses by blocking multiple levels of IFN-alpha signal transduction. J. Immunol. 162:6107–6113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mocarski E. S., Shenk T., Pass R. F. 2007. Cytomegaloviruses, p. 2701–2772 In Knipe D. M., et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Powers C., DeFilippis V., Malouli D., Fruh K. 2008. Cytomegalovirus immune evasion. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 325:333–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanchez R., Mohr I. 2007. Inhibition of cellular 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase by the herpes simplex virus type 1 Us11 protein. J. Virol. 81:3455–3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Silverman R. H. 2007. Viral encounters with 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase and RNase L during the interferon antiviral response. J. Virol. 81:12720–12729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simmen K. A., et al. 2001. Global modulation of cellular transcription by human cytomegalovirus is initiated by viral glycoprotein B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:7140–7145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Slobedman B., et al. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection and associated viral gene expression. Future Microbiol. 5:883–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slobedman B., Mocarski E. S. 1999. Quantitative analysis of latent human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 73:4806–4812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. White K. L., Slobedman B., Mocarski E. S. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated protein pORF94 is dispensable for productive and latent infection. J. Virol. 74:9333–9337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu H., Cong J. P., Mamtora G., Gingeras T., Shenk T. 1998. Cellular gene expression altered by human cytomegalovirus: global monitoring with oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:14470–14475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhu H., Cong J. P., Shenk T. 1997. Use of differential display analysis to assess the effect of human cytomegalovirus infection on the accumulation of cellular RNAs: induction of interferon-responsive RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:13985–13990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.