Abstract

Recent findings suggest that in addition to its role in packaging genomic RNA, the West Nile virus (WNV) capsid protein is an important pathogenic determinant, a scenario that requires interaction of this viral protein with host cell proteins. We performed an extensive multitissue yeast two-hybrid screen to identify capsid-binding proteins in human cells. Here we describe the interaction between WNV capsid and the nucleolar RNA helicase DDX56/NOH61. Coimmunoprecipitation confirmed that capsid protein binds to DDX56 in infected cells and that this interaction is not dependent upon intact RNA. Interestingly, WNV infection induced the relocalization of DDX56 from the nucleolus to a compartment in the cytoplasm that also contained capsid protein. This phenomenon was apparently specific for WNV, as DDX56 remained in the nucleoli of cells infected with rubella and dengue 2 viruses. Further analyses showed that DDX56 is not required for replication of WNV; however, virions secreted from DDX56-depleted cells contained less viral RNA and were 100 times less infectious. Together, these data suggest that DDX56 is required for assembly of infectious WNV particles.

INTRODUCTION

West Nile virus (WNV), a member of the Flaviviridae family, is a mosquito-transmitted pathogen that causes significant morbidity in humans and animals. Following an outbreak in the New York City area in 1999 (12), WNV has quickly emerged as the most important vector-transmitted viral pathogen in North America. Moreover, an increase in disease severity is associated with the North American strains of WNV (24), suggesting that they are more virulent than Old World strains. A molecular understanding of how WNV causes disease is starting to emerge (reviewed in references 7 and 25), and key host factors that control the innate immune response to infection have been identified (8, 26). Similarly, a number of antiviral strategies have shown promise at the preclinical stage (6), but as yet, there are no WNV-specific treatments or approved vaccines for use in humans.

Similar to all other RNA viruses, flaviviruses are “gene poor,” and as such, are highly reliant on host cells for most aspects of replication and virus assembly (reviewed in reference 1). Interactions between multifunctional viral proteins and host cell proteins drive replication and in some cases may result in damage to the host cell. Although comparatively little is known about WNV virus-host interactions at the cellular level, recent evidence suggests that the capsid protein is a pathogenic determinant (5, 20, 28, 31) that interacts with a multitude of host cell proteins. Undoubtedly, elucidating the interactions between this viral protein and host cell proteins will contribute to our understanding of WNV disease and may reveal potential targets for antiviral therapy. Among the capsid-binding host proteins are the phosphatase inhibitor I2PP2A (10), Jab1, a COP9 signalosome subunit (21), exocyst component hSec3p (5), and the E3 ubiquitin ligase MKRN1 (14). Based on analogy with the hepatitis C virus capsid/core protein, which reportedly binds to more than 20 host proteins (27), it is likely that the list of known WNV capsid-binding proteins is incomplete. To this end, we conducted a yeast two-hybrid screen to identify host cell-encoded capsid-binding proteins. From this screen, we identified the nucleolar helicase DDX56 as a binding partner of the WNV capsid. Although DDX56 is not required for WNV replication, it was shown to be important for assembly of infectious virus particles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The following reagents were purchased from the respective suppliers: protein A-Sepharose, protein G-Sepharose, and glutathione-Sepharose from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB (Piscataway, NJ); general lab chemicals, MG132, leptomycin B, and bafilomyicn A were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail and RNase A from Roche Diagnostics (Laval, Quebec, Canada); ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), Lipofectamine 2000, media, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) for cell culture from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); PerFectin transfection reagent from Genlantis (San Diego, CA); HEK 293T, A549, and BHK21 cells from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA); human full-length verified DDX56 cDNA clone from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL); Matchmaker pretransformed normalized human universal cDNA library, Tet-free FBS, and yeast strains AH109 and Y187 from Clontech (Mountain View, CA).

Antibodies.

The following primary antibodies were obtained from the respective sources: mouse monoclonal antibody against the nucleolar helicase DDX56/NOH61 from PROGEN Biotechnik (Heidelberg, Germany); pooled human anti-dengue virus 2 (DV2) convalescent-phase sera (described previously [9]); mouse monoclonal antibodies against West Nile virus proteins NS3 and NS3/2b from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); rabbit polyclonal antibodies to nucleolin, mouse monoclonal antibodies to β-actin and RNA helicase A, and also glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); mouse monoclonal anti–glutathione S-transferase (GST) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); rabbit polyclonal antibodies to WNV and rubella virus (RV) capsid proteins generated in this laboratory (4, 10); mouse monoclonal anti-myc (9E10) from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and donkey anti-human IgG conjugated to Texas Red were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, chicken anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594, and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Plasmid constructions.

Plasmids were constructed using PCR and standard subcloning techniques. The primers used for the PCRs are listed in Table 1. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer name | Sequence | Restriction enzyme sitea | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-BD-Capsid-F | 5′-GAAGGAATTCATGTCTAAGAAACCAG-3′ | EcoRI | Cloning |

| DNA-BD-Capsid-R | 5′-CGGTCTGCAGCTATCTTTTCTTTTG-3′ | PstI | Cloning |

| DDX56-myc-F | 5′-CTATGAATTCCGCCACCATGGAGGACTCTGAAGCACTG-3′ | EcoRI | Cloning |

| DDX56-myc-R | 5′-GCGTGGATCCGGAGGGCTTGGCTGTGGGTCTG-3′ | BamHI | Cloning |

| WNV-env-F | 5′-TCAGCGATCTCTCCACCAAAG-3′ | qRT-PCR | |

| WNV-env-R | 5′-GGGTCAGCACGTTTGTCATTG-3′ | qRT-PCR | |

| Cyclophilin-F | 5′-TCCAAAGACAGCAGAAAACTTTCG-3′ | qRT-PCR | |

| Cyclophilin-R | 5′-TCTTCTTGCTGGTCTTGCCATTCC-3′ | qRT-PCR | |

| GAPDH-F | 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ | Semi-qRT–PCR | |

| GAPDH-R | 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ | Semi-qRT–PCR | |

| DDX56-F | 5′-CTATGAATTCGCCACCATGGAGGACTCTGAAGCACTG-3′ | Semi-qRT–PCR | |

| DDX56-R | 5′-GCGTGGATCCAAGGGTAACCGGGTTATGTAA-3′ | Semi-qRT–PCR |

Restriction sites in the sequences are underlined.

Yeast expression plasmids.

To construct the bait plasmid pGBKT7-Capsid, which was used for yeast two-hybrid screening, the cDNA for the mature WNV capsid protein (amino acid [aa] residues 1 to 105) was amplified by PCR with primers DNA-BD-Capsid-F and DNA-BD-Capsid-R using the template plasmid pBR-5′Eg101, which encodes the 5′ region of the Eg101 WNV genome (10). The resulting PCR product was digested with EcoRI and PstI and then subcloned into the bait vector pGBKT7 (Clontech).

Mammalian cell expression plasmids. (i) WNV capsid constructs.

Construction of pCMV5-Capsid and pEBG-GST-Capsid has been described previously (10).

(ii) DDX56 constructs.

The cDNA encoding full-length human DDX56 (aa 1 to 547) was amplified by PCR using pCMV-SPORT6-DDX56 (clone ID 345647; Open Biosystems) as a template and the primer pair DDX56-myc-F and DDX56-myc-R. The resulting product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and then subcloned into the vector pcDNA3.1(-)-myc-His A (Invitrogen) to yield pcDNA3.1(-)/DDX56-myc.

Yeast two-hybrid screening.

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed with the Matchmaker GAL4 yeast two-hybrid system 3 using a pretransformed normalized human universal cDNA library (Clontech). In brief, the bait plasmid pGBKT7-Capsid was transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 and transformants were mated with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y187 that had been pretransformed with the human universal cDNA library. Candidates for two-hybrid interaction were initially selected on medium-stringency selection SD medium (-His, -Leu, and -Trp) and further confirmed on high-stringency selection SD medium (-Ade, -His, -Leu, and -Trp) containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-galactopyranoside (X-Gal). The prey plasmids were isolated from positive blue clones and then retransformed with or without pGBKT7-Capsid into AH109 for further interaction confirmation. Clones that grew on the high-stringency selection SD plate (-Ade, -His, -Leu, and -Trp) containing X-Gal only in the presence of pGBKT7-Capsid were characterized by restriction endonuclease digestion and DNA sequencing using the 5′-T7 sequencing primer (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′). Sequences were compared to those in the GenBank database.

Mammalian cell culture and transfections.

HEK 293T, A549, and BHK21 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS, 4.5 g/liter d-glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate, 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected using PerFectin transfection reagent as described by the manufacturer. A549 cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 as described by the manufacturer.

Coimmunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assays.

HEK 293T cells (1.2 × 106) were seeded into 100-mm-diameter dishes and the next day were transfected with expression plasmids (8 μg) using PerFectin regent. After 48 h, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 1 mM fresh dithiothreitol) containing protease inhibitors on ice for 30 min. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge at 4°C. Small aliquots of the clarified lysates were kept for loading controls. The remaining lysates were precleared with protein G-Sepharose or protein A-Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4°C before sequential incubation with antibodies for 3 h and then protein G-Sepharose beads or protein A-Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4°C. Where indicated, samples were treated with RNase A (20 μg/ml) for 1 h prior to immunoprecipitation. For the GST pull-down experiments, cleared lysates were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads for 2 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates and GST pull-down products were washed three times with lysis buffer before the bound proteins were eluted by boiling in protein sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for Western blotting.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Transfected or infected A549 cells grown on coverslips were processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy at 48 h after transfection or infection. Cells were washed in PBS containing 0.5 mM Ca2+ and 1.0 mM Mg2+ and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Samples were quenched with PBS containing 50 mM ammonium chloride and then washed two times with PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+. Cell membranes were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min before sequential incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, with washes in between. Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated chicken anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit, and/or Texas Red-conjugated donkey anti-human IgG. Coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides by using ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI, and samples were examined using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope or Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. Captured images were processed using Image-Pro MC5.1, Image J, and LAS AF Lite software.

RNA interference.

A549 or HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific for human DDX56 mRNA (Thermo Scientific Dharmacon RNA Technologies, Lafayette, CO) or nonsilencing control siRNAs Alexa Fluor 488 (Qiagen-Xeragon, Valencia, CA). The siRNAs (200 nM) were mixed with Lipofectamine reagent prior to addition to cells.

Stable cell lines with reduced levels of DDX56 were constructed by transduction with lentiviruses encoding a DDX56-specific shRNAmir (clone Id V3LHS_353977) from Open Biosystems. A negative-control cell was line was established by transducing with a lentivirus encoding a nonsilencing shRNAmir (catalog number RHS4346; Open Biosystems). The pGIPZ plasmid containing shRNAmir constructs was cotransfected together with psPAX2 and pMD2.G into HEK 293T cells. The psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmids encode retroviral packaging components and the vesicular stomatitis G protein, respectively. They were developed in the laboratory of Didier Trono (École Polytechnique Fédérale De Lausanne) and are distributed by Addgene Inc. (Cambridge, MA). After 48 h, virus-containing supernatants were used to transduce HEK 293T or A549 cells. Puromycin (1 μg/ml) was added to the transduced cells after 48 h. Puromycin-resistant cells were maintained in 0.25 μg/ml of puromycin.

Virus infection.

WNV strain NY99 and DV2 were kindly provided by Mike Drebot at the Public Health Agency of Canada (Winnipeg, MB, Canada). All WNV and DV2 manipulations were performed under level 3 and level 2 containment conditions, respectively. RV infections were performed as described previously (11). Cells were infected using a multiplicity of infection between 2 and 5.

To recover WNV particles from infected cells, medium from infected cells was precleared of cell debris by centrifugation for 10 min at 2,500 × g, after which the resulting supernatants were passed through 0.45-μm filters. Virus was inactivated by exposure to UV light in the biosafety cabinet for 1 h to allow transport of the material out of the level 3 facility. WNV virions were then recovered from the clarified medium by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h.

WNV plaque assay.

The day before infection, BHK21 cells (2 × 105 per well) were seeded into six-well plates. Culture supernatants from WNV-infected A549 or HEK 293T cells which were transfected with DDX56-specific or control siRNAs (24 h previously) were 10-fold serially diluted in serum-free DMEM on ice. To each well, 200 μl of virus-containing dilution was added, and plates were placed in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 h with occasional mixing. After 1 h, 2.5 ml of DMEM containing 2% methylcellulose and 2% FBS was added to each well. After 5 days, cells were fixed with 50% (vol/vol) methanol for 4 h and then stained with 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet in 20% (vol/vol) methanol for 2 h. The cells were then rinsed with water, and the number of plaques in each well was counted.

RV plaque assay.

RV plaque assays were conducted using BHK21 cells as described previously (16).

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA from WNV-infected cells or crude virion preparations was isolated with Tri reagent (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prior to reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), 1 μg of total RNA was treated with 2 U of amplification-grade DNase I (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's recommendations. The DNase I-treated RNA samples were reverse transcribed to single-stranded cDNA by using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase cDNA synthesis kit and random primers (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative PCRs were conducted on a MX3005P thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using a PerfecCTa SYBR green supermix low Rox real-time PCR kit (Quanta Biosciences). Reactions were carried out in triplicate in a total volume of 25 μl containing 5 μl of cDNA and 100 nM each gene-specific primer. To amplify a region of the WNV envelope gene, the primers WNV-env-F and WNV-env-R were used (Table 1). The amplification cycles consisted of an initial denaturing cycle at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 62°C, and 40 s at 72°C. Fluorescence was quantified during the 62°C annealing step, and the product formation was confirmed by melting curve analysis (57°C to 95°C). As an internal control, levels of the housekeeping gene product cyclophilin A were determined. Amplification was performed using the primers Cyclophilin F and Cyclophilin R (Table 1). The amplification cycles for cyclophilin A mRNA detection consisted of an initial denaturing cycle at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 40 s at 72°C. Fluorescence was quantified during the 60°C annealing step, and the product formation was confirmed by melting curve analysis (57°C to 95°C).

Quantification of the samples was performed using the two standard curves method (30), and the relative amount of WNV genomic RNA was normalized to the relative amount of cyclophilin A mRNA. Three independent PCR analyses were performed for each sample.

To determine how WNV infection affected levels of DDX56 mRNA, semiquantitative PCR was employed. Total RNA (1 μg) extracted from mock- or WNV-infected cells was used for reverse transcription as described above. Five percent of the resulting RT products was subjected to PCR (25 cycles) using primer pairs DDX56-F/DDX56-R and GAPDH-F/GAPDH-R to amplify DDX56 and GAPDH cDNAs, respectively (Table 1). Products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

The nucleolar helicase DDX56 interacts with the WNV capsid protein.

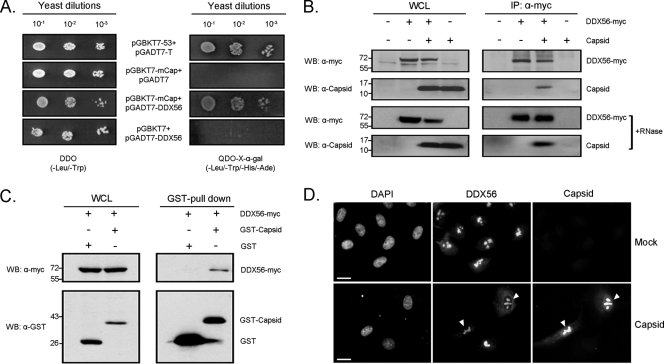

We used a stringent yeast two-hybrid multitissue screen to identify human proteins that interact with the WNV capsid protein. One of the putative capsid protein interactors was the nucleolar helicase DDX56/NOH61 (33). DDX56 is a member of the DEAD box family of RNA helicases and has been implicated in assembly of 60S ribosomal subunits. As the data in Fig. 1A indicate, binding between WNV capsid and DDX56 was robust, as evidenced by the fact that they interacted under the most stringent yeast two-hybrid conditions. The capsid-DDX56 interaction was confirmed by reciprocal coimmunoprecipitations and GST pull-down assays from transfected cells (Fig. 1B and C). These analyses also showed that intact RNA was not required for the stability of capsid-DDX56 complexes. A large pool of WNV capsid protein localizes to nucleoli of infected cells (10, 29), and therefore we examined the distributions of DDX56 and WNV capsid in transfected A549 cells. As expected, we observed extensive colocalization between DDX56 and WNV capsid protein in the nucleoli (Fig. 1D, arrowheads).

Fig. 1.

The WNV capsid protein interacts with the host cell protein DDX56. (A) The cDNA for mature capsid (mCap) was cloned into pGBKT7, which was then cotransformed with empty vector (pGADT7) or pGADT7-DDX56 into the AH109 yeast strain. Serial dilutions of the transformants were plated onto double-dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (DDO) or quadruple-dropout medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, histidine, and adenine (QDO). Further evidence of the interaction was obtained by assaying for α-galactosidase activity on QDO medium. Positive controls for this system were p53 (pGBKT7-53) and simian virus 40 large T antigen (pGADT7-T). (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with or without plasmids encoding WNV capsid or myc-tagged DDX56. At 48 h posttransfection whole-cell lysates (WCL) and mouse anti-myc immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (WB) with anti-myc (α-myc) or rabbit anti-capsid antibodies. Where indicated, samples were treated with RNase A prior to immunoprecipitation. Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are shown on the left. (C) To show reciprocal copurification of capsid/DDX56 complexes, HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GST-capsid, GST, and/or DDX56-myc. Lysates were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads, and then bound proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-myc or anti-GST antibodies. Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated. (D) Forty hours posttransfection with a plasmid encoding WNV capsid, A549 cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence using mouse anti-DDX56 and rabbit anti-capsid antibodies. Primary antibodies were detected with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 488 and chicken anti-mouse Alexa 594. Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI. Images were captured with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope. Bars, 10 μm.

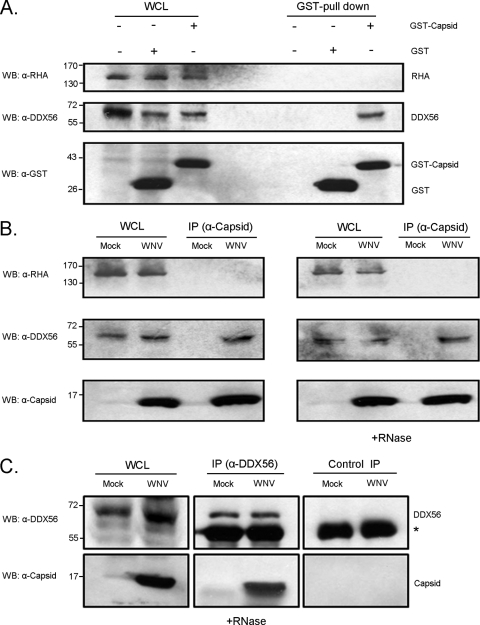

To determine if the WNV capsid interacts with nucleolar RNA helicases in a nonspecific manner, we immunoblotted for RNA helicase A in the GST-capsid pull-down assays. Whereas endogenous DDX56 was readily pulled down with GST-capsid, interaction between RNA helicase A and capsid was not detected (Fig. 2A). Finally, reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments using WNV-infected cells confirmed that capsid binds to endogenous DDX56 in the absence of RNA (Fig. 2B and C).

Fig. 2.

WNV capsid protein forms a stable complex with endogenous DDX56. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GST or GST-WNV capsid. At 48 h posttransfection whole-cell lysates (WCL) and GST-pull-down products were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with rabbit anti-capsid, mouse anti-DDX56, or mouse anti-RNA helicase A (α-RHA). (B and C) HEK 293T cells were infected with the NY99 strain of WNV (MOI, 5) and 48 h later lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) with rabbit anti-capsid antibody (B) or mouse anti-DDX56 (C) followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies to DDX56, RHA, or capsid. The position of the IgG heavy chain is indicated by the asterisk. Nonimmune mouse serum was used for the negative-control IP. WCL, whole-cell lysate. Where indicated, samples were treated with RNase A prior to immunoprecipitation. Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated.

WNV infection leads loss of nucleolar DDX56.

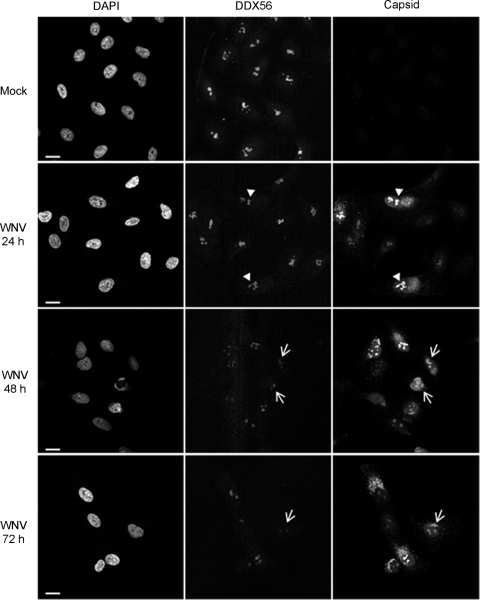

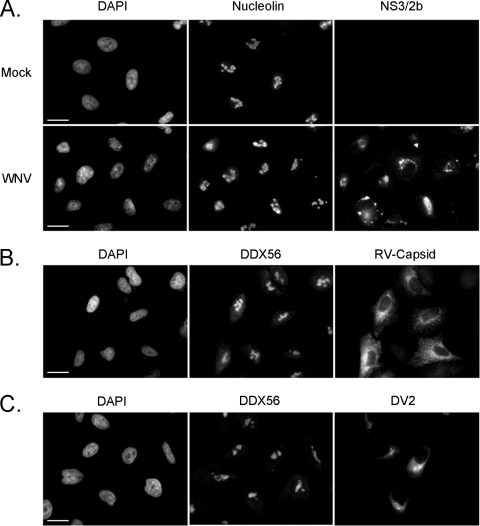

Next, we set out to confirm that capsid protein and DDX56 colocalized to nucleoli of infected cells. Indeed, at 24 h postinfection, the localizations of DDX56 in mock- and WNV-infected cells were very similar. Distinct nucleolar pools of capsid proteins that overlapped with DDX56 were also evident at this time point (Fig. 3, arrowheads). However, starting at 48 h postinfection, a diminished signal intensity of nucleolar DDX56 was clearly evident, and by 72 h, many infected cells exhibited little or no detectable DDX56 in nucleoli (Fig. 3, arrows). Interestingly, at 72 h postinfection, many more cells with cytoplasmically localized capsid protein were evident. To determine if WNV infection led to a general loss of nucleolar components, we monitored the localization of another nucleolar resident protein, nucleolin. The data in Fig. 4A indicate that WNV infection did not cause a general loss of nucleolar components. Next, we questioned whether infection with other positive-strand RNA viruses led to loss of DDX56 from nucleoli. A549 cells that were infected with rubella virus (Fig. 4B) or dengue virus 2 (Fig. 4C) were subjected to analyses by indirect immunofluorescence. In contrast to WNV-infected cells, infection with these two viruses did not result in detectable loss of DDX56 from the nucleoli. Similarly, infection of Huh7.5 cells with hepatitis C virus did not appear to affect the nucleolar pool of DDX56 (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

WNV infection results in depletion of the nucleolar pool of DDX56. A549 cells were infected with WNV (MOI, 2), and at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence by using rabbit and mouse antibodies to capsid and DDX56, respectively. Primary antibodies were detected using goat anti-mouse Alexa 647 and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 488. Images were captured using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal scanning microscope. Arrowheads indicate colocalization between DDX56 and WNV capsid in nucleoli. Arrows point to infected cells that have decreased levels of DDX56 in the nucleoli. Bars, 10 μm.

Fig. 4.

(A) WNV-infected cells were detected by using a mouse monoclonal antibody to NS3/2b, and nucleolin was detected with a rabbit antibody. (B and C) A549 cells were infected with RV (B) or DV2 (C), and 48 h postinfection cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence by using mouse antibodies to DDX56 and rabbit RV capsid or human antibodies DV2, respectively. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope. Bars, 10 μm.

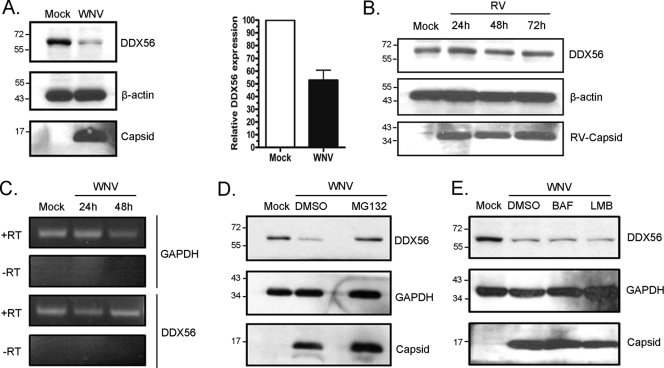

The loss of DDX56-specific immunofluorescence from the nucleolar compartment in response to WNV infection could be due to dispersion of DDX56 over a larger volume in the cytoplasm after transport of this protein from the nucleus. Alternatively, DDX56 could be degraded following transport to the cytoplasm. The data in Fig. 5A show that at 48 h, mock-treated cells contained approximately twice as much DDX56 protein as WNV-infected cells. In contrast, infection of A549 cells with rubella virus had no apparent effect on DDX56 protein levels (Fig. 5B). Semiquantitative PCR analyses revealed that DDX56 mRNA levels were not decreased by infection, suggesting that WNV-induced loss of DDX56 occurred at the posttranscriptional level (Fig. 5C). Treatment of infected cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prevented WNV-induced loss of DDX56, whereas an inhibitor of lysosomal degradation (bafilomycin A) had no effect (Fig. 5D and E). Given that proteasome degradation occurs in the cytoplasm, we questioned whether we could detect DDX56 in the cytoplasm of WNV-infected cells treated with MG132. As the data in Fig. S1 (arrowheads) in the supplemental material show, in some cells, colocalization of capsid and DDX56 on cytoplasmic reticular structures occurred when the proteasomal degradation system was inhibited. Together, these data suggest that WNV infection causes transport of DDX56 from the nucleus to cytoplasm, followed by degradation in the proteasome. Treatment with the nuclear export inhibitor leptomycin B (Fig. 5E) did not block WNV-induced degradation of DDX56; however, this inhibitor blocks only one of multiple nuclear export pathways.

Fig. 5.

WNV infection induces proteasome-dependent degradation of DDX56. (A) A549 cells were infected with WNV (MOI, 2), and 48 h later cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses for DDX56 and β-actin. Data from three independent experiments were used to determine the normalized level of DDX56 (relative to β-actin). Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated. (B) A549 cells were infected with rubella virus (MOI, 2) for 24 to 72 h, after which cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE before immunoblotting for DDX56, rubella virus capsid protein, and β-actin. (C) Total RNA was extracted from mock- or WNV-infected cells at 24 and 48 h postinfection. After DNase treatment, RNA was subjected to reverse transcription or mock treatment before semiquantitative PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining were used to detect PCR products. GAPDH mRNA served as the internal control. (D and E) A549 cells were infected with WNV and 24 h later were treated with 50 μM MG132, 200 nM bafilomycin A (BAF), 50 ng/ml leptomycin B (LMB), or the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for a further 24 h. Lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-capsid, GAPDH, or DDX56.

Expression of DDX56 is important for infectivity of WNV virions.

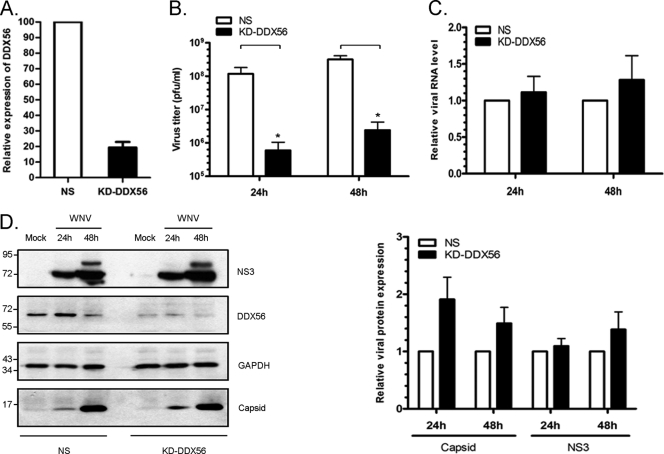

As a first step toward understanding the potential role of DDX56 in WNV replication, RNA interference was used to reduce cellular levels of DDX56 in HEK 293T and A549 cells. In cells transiently transfected with pooled DDX56-specific siRNAs, levels of DDX56 remained low for up to 96 h without any significant effect on cell viability (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Because DDX56 is not required for cell growth in vitro, we used an shRNAmir-contaning lentivirus to construct stable polyclonal cell lines with reduced DDX56 (Fig. 6A). The DDX56 knockdown and a nonsilencing control cell line were infected with WNV, and at various times cell supernatants were harvested for viral titer assays. Downregulation of DDX56 in HEK 293T cells was associated with a >100-fold decrease in viral titers (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained using HEK 293T and A549 cells transiently depleted of DDX56 by using pooled siRNAs (see Fig. S2), indicating that the importance of this helicase for production of WNV is not limited to one cell type.

Fig. 6.

Stable polyclonal HEK 293T cells with reduced DDX56 (KD-DDX56) were obtained after transduction with a lentivirus encoding a DDX56-specific shRNAmir. A matched nonsilencing control cell line (NS) was produced using a lentivirus encoding a control shRNAmir that has no homology to any mammalian genes. (A) Relative levels of DDX56 protein were determined by immunoblotting, and the results from three independent experiments were quantitated. (B) Cell lines were infected with WNV (MOI, 2) for up to 48 h, after which cell supernatants were collected and used for plaque assays. *, P < 0.05. Cell lysates were subjected to qRT-PCR (C) and immunoblot analyses (D) to determine relative levels of genomic RNA and viral proteins, respectively. Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated. Error bars represent standard errors from three independent experiments.

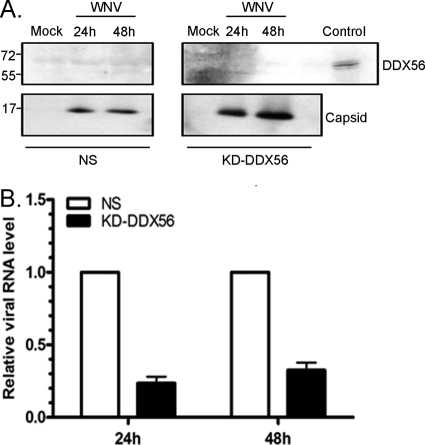

To determine if the reduction in secretion of infectious virions was due to decreased synthesis of viral RNA or proteins, infected cell lysates were subjected to quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and immunoblot analyses, respectively. Surprisingly, loss of DDX56 did not have a significant effect on the production of viral genomic RNA (Fig. 6C). Similarly, the steady-state levels of WNV structural proteins (capsid) and nonstructural proteins (NS3) were not lower in DDX56-depleted cells and, in some cases, were slightly higher (Fig. 6D). Together, these data indicate that DDX56 is not required for replication of WNV but rather may be involved in assembly and/or secretion of infectious virus particles. It is also possible that virus assembly is not affected but that the virions that are secreted from DDX56-depleted cells are less infectious. To distinguish between these possibilities, virus particles secreted from the infected cells were recovered and subjected to immunoblot analyses with anti-capsid and anti-DDX56 antibodies. The data in Fig. 7A show DDX56 was not incorporated into WNV virions and that knockdown of DDX56 protein did not inhibit assembly and secretion of WNV particles. However, the levels of viral RNA in WNV virions secreted from DDX56 knockdown cells were 3 to 4 times lower than in virions isolated from nonsilencing control cells (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

(A) WNV virions were recovered from precleared conditioned medium from infected stable DDX56 knockdown (KD-DDX56) and nonsilencing control (NS) HEK 293T cells by ultracentrifugation. (A) The crude virion preparations were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses with rabbit anti-capsid antibody and mouse anti-DDX56. Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated. (B) Levels of viral genomic RNA in the virions were determined by qRT-PCR. The average relative levels of viral RNA (normalized to capsid level) from three independent experiments (each conducted in triplicate) were quantitated. Bars indicate standard error values.

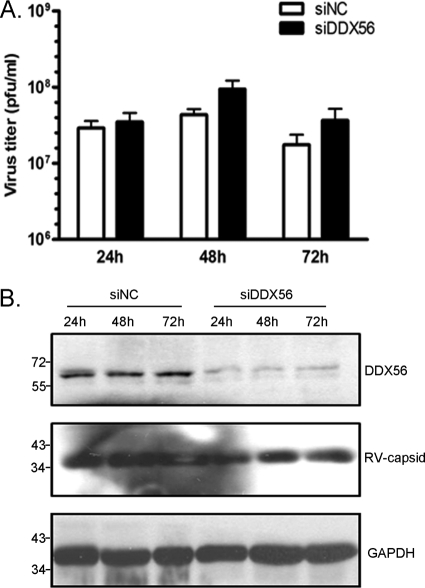

Finally, we determined whether DDX56 expression is required for replication and/or infectivity of another positive-strand RNA virus. The data in Fig. 8 show that siRNA-mediated knockdown of DDX56 did not affect replication or infectivity of rubella virus. Together, these experiments indicate depletion of DDX56 from infected cells results in secretion of WNV virions with significantly lower infectivity.

Fig. 8.

DDX56 is not required for replication of rubella virus or assembly of infectious virions. A549 cells were transfected with nonsilencing control (siNC) or DDX56 siRNAs and then 24 h later were infected with rubella virus (MOI, 2). (A) Cell lysates and conditioned media were harvested for up to 72 h postinfection, and levels of infectious virus were determined by plaque assay. (B) Immunoblot analysis was used to determine relative levels of viral (RV-capsid) and cellular proteins (DDX56 and GAPDH [loading control]) in cell lysates. Positions of molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The genetic simplicity of WNV and related flaviviruses necessitates that they be highly reliant on host cell proteins for multiple aspects of their replication cycles. Indeed, a large-scale siRNA screen revealed that expression of more than 280 human genes is required for WNV replication (15). While genome-scale screens are invaluable for understanding the overall complexity of virus-host interactions, the mechanisms by which individual host proteins contribute to virus replication cannot usually be discerned by these approaches. In the present study, we focused on functional interactions between the WNV capsid protein and host cell proteins. Over the last 5 years, this virus protein has been implicated in a variety of processes that may contribute to pathogenesis, including induction of apoptosis and breakdown of cellular tight junctions (20, 28, 31). In all cases, it is expected that interactions between capsid protein and host cell proteins are required for these processes. To understand more about the nonstructural functions of the WNV capsid protein, we conducted a large-scale yeast two-hybrid screen to identify interacting host cell proteins. The nucleolar helicase DDX56 is one such protein that appears to have a critical role in assembly of infectious virions.

Because of their role in packaging viral genomes into nucleocapsids, capsid proteins are essential for virus assembly. Besides direct binding to viral RNA, it is now becoming clear that the capsid proteins of RNA viruses may also affect production of infectious virions through interactions with host cell proteins. For example, data from our laboratory suggest that interactions between the host protein p32 and the rubella virus capsid protein are important for virus replication (3). Similarly, interactions between flavivirus capsids and host proteins are critical for virus replication and/or assembly. The DEAD box helicase DDX3 binds to the hepatitis C virus capsid protein (19, 22, 32) and, more recently, has been shown to be important for replication of viral RNA (2). A genome-wide screen for host cell factors revealed that the host cell helicases DDX28, DDX42, and DHX15 are important for replication of WNV and dengue virus in mammalian cells (15). However, this screen did not assay for production of infectious virus, but rather, expression of viral proteins. Because DDX56 is not important for replication of WNV genomic RNA or viral protein synthesis, it could not have been identified in this type of RNA inhibitor screen. Instead, DDX56 appears to play an essential postreplication role in assembly of infectious WNV virions.

Recent studies suggest that flavivirus morphogenesis does not simply involve the stochastic interaction between genomic RNA, capsid proteins, and viral membrane proteins. In fact, virus assembly is coupled with replication of viral RNA such that only genomic RNA that is derived from active replication complexes is selectively packaged into virions (13). This process is dependent in part on the viral helicase NS3, but interestingly, the mechanism differs among flaviviruses. For example, production of infectious Kunjin virus particles requires expression of NS3 protein in cis (17). In contrast, assembly of infectious yellow fever virus particles is not dependent on cis activity of NS3 and, furthermore, the helicase activity of this protein is not even required for trans-complementation (23). Based on the present study, cellular helicases such as DDX56 are also required for infectivity of WNV virions at a postreplication step.

In cells that are depleted of DDX56, assembly and secretion of WNV particles was not dramatically affected; however, the infectivity of the virus particles was >100-fold lower than for virions secreted from control cells. We are unaware of other cellular helicases that function in assembly of flavivirus particles, but it was recently reported that the DDX24 helicase is important for packaging HIV RNA into virions (18). Our data suggest that DDX56 may also be important for packaging viral RNA in WNV virions. Similar to what we observed for knockdown of DDX56, depletion of DDX24 did not affect synthesis of HIV proteins or secretion of virus particles, but the infectivity of HIV particles released from DDX24-depleted cells was significantly lower. However, given that loss of DDX24 only reduces HIV titers 3-fold (18), it would appear that DDX56 is more important for morphogenesis of infectious WNV virions than DDX24 is for HIV infectivity.

The precise mechanism by which DDX56 facilitates production of infectious WNV virions remains to be determined. However, based upon the observation that when proteasomal degradation is blocked, DDX56 accumulates on capsid-positive structures in the cytoplasm, it is tempting to consider the following scenario: WNV infection induces the translocation of DDX56 from the nucleolus to the cytoplasm, where it interacts with a pool of capsid protein at the site of virus assembly, the endoplasmic reticulum. Interaction between capsid protein and DDX56 stimulates incorporation of genomic RNA into nucleocapsids through disruption of secondary structure or by facilitating capsid-RNA complex formation. DDX56 is not incorporated in WNV virions, suggesting that its association with capsid is transient in nature. Accordingly, dissociation of DDX56 from capsid proteins that are incorporated into nascent virions may trigger proteasome-dependent turnover of DDX56 as a result of its inadvertent exposure to the cytoplasmic degradation machinery. Although expression of capsid alone does not result in translocation of DDX56 from the nucleolus to the cytoplasm (data not shown), it seems likely that this viral protein is required for this process. Indeed, at later times during infection, the accumulation of capsid in the cytoplasm coincided with the loss of DDX56 from the nucleolus.

Because RNA viruses are so reliant upon host cell proteins for replication and assembly, targeting host factors may hold great promise for developing novel antiviral therapies. One central caveat of this strategy is that it must be possible to downregulate the level of the host-encoded virus cofactor or block its activity without killing the host cell. Knocking down DDX56 levels by RNA interference doesn't appear to be detrimental to cell viability in vitro, and as such, it remains a potential candidate for anti-WNV therapy. However, redistribution and hijacking of DDX56 function in the cytoplasm is not a common strategy used by other positive-strand RNA viruses and, as such, targeting this host protein as a means to block virus replication has limited applications. Nevertheless, identification of capsid-binding proteins may serve as a useful starting point for development of novel antivirals for WNV as well as other RNA viruses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eileen Reklow and Valeria Mancinelli for technical assistance and Mike Drebot (Public Health Agency of Canada) for providing West Nile virus and dengue virus stocks.

Z.X. is supported by a Graduate Studentship from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. This work is supported by a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to T.C.H.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 16 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahlquist P., Noueiry A. O., Lee W. M., Kushner D. B., Dye B. T. 2003. Host factors in positive-strand RNA virus genome replication. J. Virol. 77:8181–8186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ariumi Y., et al. 2007. DDX3 DEAD-box RNA helicase is required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 81:13922–13926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beatch M. D., Everitt J. C., Law L. J., Hobman T. C. 2005. Interactions between rubella virus capsid and host protein p32 are important for virus replication. J. Virol. 79:10807–10820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beatch M. D., Hobman T. C. 2000. Rubella virus capsid associates with host cell protein p32 and localizes to mitochondria. J. Virol. 74:5569–5576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhuvanakantham R., Li J., Tan T. T., Ng M. L. 2010. Human Sec3 protein is a novel transcriptional and translational repressor of flavivirus. Cell. Microbiol. 12:453–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diamond M. S. 2009. Progress on the development of therapeutics against West Nile virus. Antiviral Res. 83:214–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diamond M. S. 2009. Virus and host determinants of West Nile virus pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fredericksen B. L., Smith M., Katze M. G., Shi P. Y., Gale M., Jr 2004. The host response to West Nile virus infection limits viral spread through the activation of the interferon regulatory factor 3 pathway. J. Virol. 78:7737–7747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. He R. T., et al. 1995. Antibodies that block virus attachment to Vero cells are a major component of the human neutralizing antibody response against dengue virus type 2. J. Med. Virol. 45:451–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hunt T. A., et al. 2007. Interactions between the West Nile virus capsid protein and the host cell-encoded phosphatase inhibitor, I2PP2A. Cell. Microbiol. 9:2756–2766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ilkow C. S., Mancinelli V., Beatch M. D., Hobman T. C. 2008. Rubella virus capsid protein interacts with poly(A)-binding protein and inhibits translation. J. Virol. 82:4284–4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaye K., Mojica A. M. 2000. West Nile virus: a briefing. City Health Infect. NY City Dept. Health 19:1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khromykh A. A., Varnavski A. N., Sedlak P. L., Westaway E. G. 2001. Coupling between replication and packaging of flavivirus RNA: evidence derived from the use of DNA-based full-length cDNA clones of Kunjin virus. J. Virol. 75:4633–4640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ko A., et al. 2010. MKRN1 induces degradation of West Nile virus capsid protein by functioning as an E3 ligase. J. Virol. 84:426–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krishnan M. N., et al. 2008. RNA interference screen for human genes associated with West Nile virus infection. Nature 455:242–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Law L. M., Everitt J. C., Beatch M. D., Holmes C. F., Hobman T. C. 2003. Phosphorylation of rubella virus capsid regulates its RNA binding activity and virus replication. J. Virol. 77:1764–1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu W. J., Sedlak P. L., Kondratieva N., Khromykh A. A. 2002. Complementation analysis of the flavivirus Kunjin NS3 and NS5 proteins defines the minimal regions essential for formation of a replication complex and shows a requirement of NS3 in cis for virus assembly. J. Virol. 76:10766–10775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma J., et al. 2008. The requirement of the DEAD-box protein DDX24 for the packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. Virology 375:253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mamiya N., Worman H. J. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein binds to a DEAD box RNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15751–15756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Medigeshi G. R., et al. 2009. West Nile virus capsid degradation of claudin proteins disrupts epithelial barrier function. J. Virol. 83:6125–6134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oh W., et al. 2006. Jab1 mediates cytoplasmic localization and degradation of west nile virus capsid protein. J. Biol. Chem. 281:30166–30174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Owsianka A. M., Patel A. H. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein interacts with a human DEAD box protein DDX3. Virology 257:330–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patkar C. G., Kuhn R. J. 2008. Yellow fever virus NS3 plays an essential role in virus assembly independent of its known enzymatic functions. J. Virol. 82:3342–3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petersen L. R., Roehrig J. T. 2001. West Nile virus: a reemerging global pathogen. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:611–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Samuel M. A., Diamond M. S. 2006. Pathogenesis of West Nile Virus infection: a balance between virulence, innate and adaptive immunity, and viral evasion. J. Virol. 80:9349–9360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suthar M. S., et al. 2010. IPS-1 is essential for the control of West Nile virus infection and immunity. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Urbanowski M. D., Ilkow C. S., Hobman T. C. 2008. Modulation of signaling pathways by RNA virus capsid proteins. Cell Signal. 20:1227–1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Marle G., et al. 2007. West Nile virus-induced neuroinflammation: glial infection and capsid protein-mediated neurovirulence. J. Virol. 81:10933–10949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Westaway E. G., Khromykh A. A., Kenney M. T., Mackenzie J. M., Jones M. K. 1997. Proteins C and NS4B of the flavivirus Kunjin translocate independently into the nucleus. Virology 234:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong L., Medrano J. 2005. Real-Time PCR for mRNA quantification. Biotechniques 39:75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang J. S., et al. 2002. Induction of inflammation by West Nile virus capsid through the caspase-9 apoptotic pathway. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:1379–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. You L. R., et al. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein interacts with cellular putative RNA helicase. J. Virol. 73:2841–2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zirwes R. F., Eilbracht J., Kneissel S., Schmidt-Zachmann M. S. 2000. A novel helicase-type protein in the nucleolus: protein NOH61. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:1153–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.