Abstract

Middle ear cholesteatoma is a rare condition in dogs with chronic otitis. Otorrhea, otodinia, and pain on temporomandibular joint palpation are the most common clinical signs. Neurological abnormalities are often detectable. Computed tomography reveals the presence of an expansive and invasive unvascularized lesion involving the tympanic cavity and the bulla, with little or no contrast enhancement after administration of contrast mediu. Video-otoscopy may detect pearly growth or white/yellowish scales in the middle ear cavity. Surgery is the only therapy but is associated with a high risk of recurrence.

Résumé

Cholestéatome de l’oreille moyenne chez 11 chiens. Le cholestéatome de l’oreille moyenne est une affection rare et potentiellement sous-estimée chez les chiens présentant une anamnèse d’otite chronique. L’otorrhée, l’otodynie et la douleur à la palpation de l’articulation temporo-mandibulaire sont les signes cliniques les plus courants. Des anomalies neurologiques sont souvent détectables. Une tomographie par ordinateur révèle la présence d’une lésion étendue et envahissante non vascularisée affectant la cavité tympanique et la bulle avec peu ou pas d’augmentation de contraste après l’administration d’un milieu de contraste. La vidéo-otosocopie peut détecter une lésion de croissance nacrée ou des écailles blanc-jaune dans la cavité de l’oreille moyenne. La chirurgie est la seule thérapie mais elle est associée à un risque élevé de récurrence.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Middle ear cholesteatoma is a serious complication of chronic otitis media in human beings and dogs (1–4). In dogs, it is rarely reported and is possibly underdiagnosed (2–6). Neither breed nor sex predisposition has been described. A history of chronic otitis, otodinia, pain on temporomandibular joint (TMJ) palpation, and discomfort when opening the mouth are the most common clinical findings. Neurological abnormalities, including head tilt, facial palsy, and ataxia, can be detected on examination or can represent the major reason for referral (2,3,5,6).

Cholesteatoma is an epidermoid cyst lined by a pluristratified keratinizing epithelium containing keratin debris and is characterized by independent and progressive growth, causing destruction of adjacent tissue, especially bone (7). The term cholesteatoma is a misnomer because it is not a tumor (suffix-“oma”), it does not contain fat (-“stea”-) or cholesterol crystal (-“chol”-), but cholesteatoma is still used for describing this disease (7–10).

The etiopathogenesis of cholesteatoma is controversial and many theories have been proposed (1,7–9,11). In dogs, it is suggested that middle ear cholesteatoma develops according to the migration theory or the invagination theory (2,3). According to the former, migration of the stratified squamous epithelium from the external auditory meatus into the infected middle ear cavity through a perforated ear drum may produce the necessary conditions for development of cholesteatoma. According to the latter, the pars flaccida and occasionally the pars tensa of the tympanic membrane retract into the middle ear because of inflammation, negative pressure, or both, and afterwards the pocket is slowly filled by keratin thus establishing cholesteatoma (7,11).

The only possible treatment is surgery and the goal of surgery is to remove all keratin debris and stratified squamous epithelium, and to control infection. Despite surgery, the risk of recurrence is high (3,7).

This paper reports the main clinical, imaging, and pathological findings, and the surgical outcome for 11 dogs diagnosed with and treated for middle ear cholesteatoma.

Materials and methods

Eleven dogs were identified that had a histologic diagnosis of cholesteatoma. The dogs had been presented to the School of Veterinary Medicine, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy, between January 2001 and July 2007 for investigation of chronic otitis unresponsive to topical and systemic therapy. Medical records were reviewed for signalment, history, and physical examination, radiological and video-otoscopy findings, micro-biological results, histopathological features, treatment, and outcome. Middle ear cholesteatoma was bilateral in 1 dog and unilateral in 10 dogs.

All dogs underwent radiological investigation and video-otoscopy under general anesthesia. The surgical procedures performed were total ear canal ablation and lateral bulla osteotomy (TECALBO) and ventral bulla osteotomy (VBO). During surgery, swabs for bacterial culture and susceptibility and samples for histological examination were collected from the middle ear cavity. Both fresh samples and samples in 10% formalin were submitted for histopathology. Follow-up consisted of clinical examination and telephone interviews.

Results

Signalment and clinical findings

Two dogs were medium-sized cross-breeds, and 9 dogs belonged to specific breeds (pug, flat-coated retriever, poodle, Afghan greyhound, cocker spaniel, schnauzer, weimaraner, golden retriever, Labrador retriever). Seven dogs were intact males, 1 dog was a castrated male, 2 dogs were spayed females, and 1 dog was an intact female. Mean age was 7.2 y (range: 4.5 to 10 y).

All dogs had a history of chronic recurrent otitis externa, unresponsive to topical or systemic therapy over the last 3 to 30 wk (mean duration 13.3 wk). In all dogs the main signs were pawing at the ear and head shaking. During physical examination, all but one of the dogs showed algic reaction at palpation of the bulla (otodinia) and TMJ. Otorrhea was present in 8 dogs and 6 dogs showed discomfort when opening the mouth. Two dogs exhibited dysphagia. Neurological abnormalities characterized by head tilt, facial paralysis, and ataxia were detected in 5 dogs. One dog, 2 mo prior to presentation, underwent Zepp surgery (lateral ear canal resection) and at the time of referral had a draining tract beneath the surgical opening. Details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Signalment, clinical signs, duration of clinical signs, site localization, surgical technique and findings, histopathology and outcome of the 11 dogs diagnosed with middle ear cholesteatoma

| Case | Breed | Sex | Age (y) | Duration of clinical signs (wk) | Clinical signs | Neurological abnormalities | Cholesteatoma location | Surgery | Histo-pathology | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pug | M | 8 | 6 | Bilateral otorrhea, otodinia, shaking head/ear paw | Left head tilt, left facial palsy | Bilateral | TECALBO, keratin scales | Keratin | 48 mo, no recurrence |

| 2 | Cross-breed | M | 5 | 16 | Otorrhea, otodinia, discomfort opening the mouth, shaking head/ear paw, dysphagia | Left | TECALBO, keratin scales | 3 layers | 28 mo, recurrence at 5 mo (VBO) | |

| 3 | Flat-coated retriever | M | 10 | 4 | Otorrhea, otodinia, shaking head/ear paw | Left head tilt, left facial palsy, ataxia, | Left | TECALBO, keratin scales | 3 layers | 13 mo, recurrent disease not confirmed |

| 4 | Poodle | Mn | 5.5 | 24 | Otodinia, discomfort opening the mouth, dysphagia, shaking head/ear paw | Right | TECALBO, keratin scales | Keratin | 39 mo, recurrent disease at 13 mo (VBO) | |

| 5 | Afghan greyhound | M | 8 | 12 | Draining tract at surgical site, otodinia, discomfort opening the mouth, shaking head/ear paw | Left | TECALBO, keratin scales | Keratin | 34 mo, recurrences at 2 (LBO), 26 (VBO) and 36 (VBO) mo | |

| 6 | Weimaraner | Fs | 9 | 4 | Otorrhea, otodinia, shaking head/ear paw | Right | TECALBO video-assisted, keratin scales | 3 layers and CG | 2 wk | |

| 7 | Cocker spaniel | M | 6 | 3 | Otorrhea, otodinia, discomfort opening the mouth | Left head tilt, left facial palsy, ataxia | Left | TECALBO video-assisted, mass-like lesion | Keratin | 28 mo, no recurrence |

| 8 | Schnauzer | M | 5.5 | 8 | Otorrhea, otodinia, shaking head/ear paw | Left | TECALBO, mass-like lesion | 3 layers | 27 mo, no recurrence | |

| 9 | Cross-breed | Fs | 9 | 16 | Otorrhea, otodinia, discomfort opening the mouth, shaking head/ear paw | Left head tilt, left facial palsy, ataxia | Left | TECALBO, keratin scales | Keratin and CG | 22 mo, recurrence at 10 (VBO) and 14 mo (response to medical management) |

| 10 | Golden retriever | F | 4.5 | 16 | Otorrhea | Left head tilt, left facial palsy, ataxia | Left | VBO, keratin scales | 3 layers and CG | 12 mo, no recurrence |

| 11 | Labrador retriever | M | 9 | 28 | Otodinia, discomfort opening the mouth | Left | TECALBO, mass-like lesion | 3 layers and CG | 13 mo, no recurrence |

M — male intact; Mn — male neutered; F — female intact; Fs — female spayed; CG — cholesterol granuloma.

Imaging

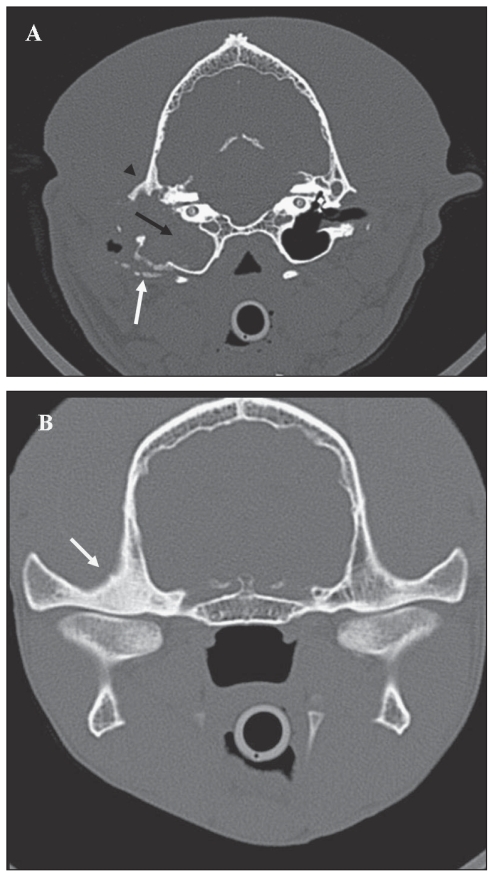

The main findings on computed tomography (CT) scan in 10 dogs (11 ears) were enlargement of the middle ear cavity, complete loss of air contrast within the middle ear cavity, and absence or minimal positive enhancement after IV injection of contrast medium (Figure 1B). Sclerosis of the petrosal bone and involvement of the epitympanic recess were also detected in all dogs, and TMJ sclerosis (Figure 1B) was detected in all but one dog. On CT scan, the bulla wall showed signs of lysis, sclerosis, or both, in 2, 6, and 3 dogs, respectively. The ear canal was completely occluded in 4 ears, partially occluded in 3 ears, and patent in 4 ears. Ventrodorsal open mouth and lateral 30º degree views of 1 dog revealed enlargement of 1 bulla, loss of air contrast within the middle ear cavity, sclerosis of the tympanic wall and petrosal bone, unremarkable contralateral bulla, and patent ear canals.

Figure 1.

A — Transverse slice obtained at the level of the ossicular chain shows, at bone setting, complete loss of air contrast associated with soft tissue density within the middle ear cavity (black arrow); enlargement of the tympanic cavity and bulla with mild osteolysis and sclerosis of the latero-ventral aspect of the bulla (white arrow), and sclerosis of the temporal bone (arrowhead); absence of air contrast in the horizontal tract of the ear canal (compared with contralateral ear canal); disappearance of the ossicular chain and mild erosion of the promontory. B — Transverse slice obtained at the level of the TMJ at bone setting; note the severe osteosclerosis of the right mandibular fossa (white arrow).

Video-otoscopy revealed total occlusion of the horizontal canal (end-stage otitis — ESO) in 4 ears, moderate stenosis of the horizontal canal in 4, and no changes in 4. The ear drum was ruptured in 8 ears. Pearly growths that differed in shape and size were found protruding from the middle ear cavity in 3 ears, and white/yellow scales were found within the middle ear cavity in 2 ears (Figure 2A,B,C).

Figure 2.

Various otoscopic appearances of middle ear cholesteatoma. A — White scales filling the middle ear cavity; B — A yellow spongy pearly growth protruding from the middle ear cavity; C — A pinkish pearly growth filling the middle ear cavity and protruding in the horizontal canal.

Surgery

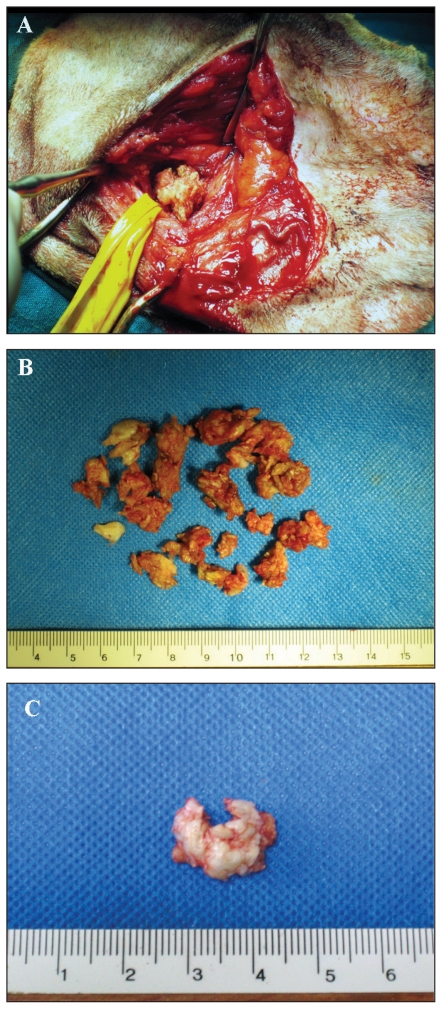

Ten dogs (11 ears) underwent TECALBO whilst 1 dog (1 ear) underwent VBO because it was a show dog. In 9 ears, the middle ear cavity was filled with a spongy yellowish material resembling keratin debris, whilst in 3 ears a mass-like lesion was removed (Figure 3A,B,C). In all dogs, the bulla was enlarged with irregular surface and had small irregular cavities hiding additional debris. In 2 dogs (2 ears), video-assisted curettage of the middle ear cavity was performed.

Figure 3.

Gross appearance of middle ear cholesteatoma during surgery. A — Spongy aspect of the keratinous material; the material spontaneously protruded after enlargement of the bulla opening; B — All material removed from the middle ear cavity in the same ear, note the keratinous appearance; C — Cyst-like aspect of cholesteatoma after surgical removal.

Bacterial culture and susceptibility

On aerobic culture of the middle ear bacteria were recovered from 8 of the 12 ears. More than 1 species of organism was isolated from 1 ear. Bacteria isolated were Staphylococcus intermedius (3 ears), Proteus mirabilis (2 ears), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1 ear), Escherichia coli (1 ear), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (1 ear). Multiple antibiotic resistances were detected.

Histopathology

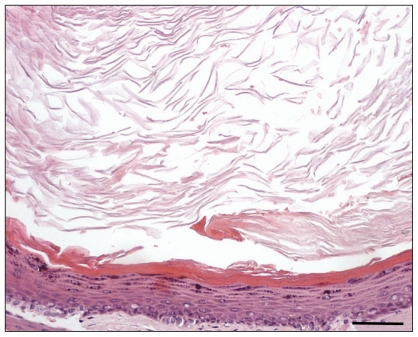

Histopathology identified keratin debris in 6 ears; in the other 6 ears there was a cystic lesion lined by a multilayered, intensely hyperplastic, keratinizing epithelium (up to 25 layers thick) and containing abundant amorphous lamellar keratin debris (Figure 4). In 4 ears, a cholesterol granuloma was also found within fibrous stromal tissue surrounding and sustaining a cystic lesion.

Figure 4.

Section of cholesteatoma. Abundant lamellar eosinophilic debris (keratin) fills a cyst lumen lined by a multilayered squamous epithelium characterized by diffuse intense hyperplasia and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. Hematoxylin and eosin, 100× (bar 1 cm = 60 μm).

Follow-up

Mean follow-up lasted 26.5 mo (2 wk to 48 mo). Surgical short-term complications such as facial palsy and dryness of the nostrils developed in 2 dogs and spontaneously resolved within 4 mo after surgery. Schirmer tear tests (STT; Essex Pharma GmbH, Munich, Germany) were normal (15 mm/min) in 1 dog and 10 mm/min in the other dog. Dryness of the nostril was attributed to temporary neurogenic dysfunction of the parasympathetic fibers of the facial nerve. Damage to those fibers most likely occurred during the curettage of the middle ear cavity. Dogs with neurological abnormalities showed persistent head tilt after surgery whilst facial palsy and ataxia resolved. One dog was lost to follow-up at 48 mo, but was reported to be free of any clinical signs on the last clinical and telephone follow-up. One dog died of an unrelated cause 2 wk after surgery; postmortem CT of the bullae showed a patent middle ear cavity and, on necropsy, the bulla surface was clean and smooth. Six dogs (7 ears) (58.33%) had resolution of middle ear disease. Recurrence of cholesteatoma was suspected in 5 dogs (5 ears) (41.66%). Mean time for recurrence was 7.5 mo (2 to 13 mo).

Clinical signs at the time of suspected recurrence were otodinia (5 dogs), head tilt (3 dogs), facial palsy (2 dogs), ataxia (2 dogs), discomfort opening the mouth (3 dogs), para-aural swelling (2 dogs), and draining tract at the surgical incision site (2 dogs). Recurrence was confirmed in 4 dogs, 2 of which had multiple recurrences, whilst 1 dog was euthanized and necropsy was not permitted. Computed tomographic scans on the other 4 dogs showed enlargement of the middle ear cavity, remodeling of the bulla due to previous surgery and active disease, and presence of soft tissue density in the middle ear cavity. A course of 7 to 10 d of empirical antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy was initiated, but there was no clinical improvement, and the patients were submitted for surgery.

Two dogs were successfully treated by VBO and at 32 and 43 mo after surgery had no signs of recurrence. One dog was diagnosed with recurrent middle ear cholesteatoma at 2, 26, and 36 mo, and otitis media at 14 mo after the first surgery. This dog was treated by LBO once and VBO 3 times, and at 7 mo after the last surgery was still exhibiting discomfort opening the mouth, had head tilt, and a draining tract at the surgical incision site, and was on and off empirical antibiotic. The other dogs had recurrent cholesteatoma at 10 mo after surgery and were treated by VBO. Four months later, otodinia, ataxia, and head tilt recurred and cholesteatoma was confirmed on CT-guided cytology and histology. The owner declined surgical treatment and the dog was treated empirically with anti-inflammatory dosage of steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Clinical signs resolved and at 17 mo after the second surgery the dog was still free of clinical signs.

Although free of clinical signs, the show dog underwent CT and video-otoscopic examination at 7 mo after surgery. The CT scan was characterized by post-surgical remodeling of the bulla and presence of radiodense tissue in the middle ear cavity; video-otoscopy showed the absence of the ear drum, and easily removable keratin scales within the middle ear cavity. At 17 mo after surgery the dog was still free of clinical signs. Only 1 dog was available for follow-up of video-assisted surgery and at 27 mo after surgery was still free of clinical signs.

Discussion

Middle ear cholesteatoma is a serious and rarely reported condition associated with chronic otitis in dogs. There is a history of chronic recurrent otitis which becomes unresponsive to topical or systemic therapy; there is no breed predisposition, but there is a predominance of males (2–6). As in humans, there is no explanation for the male predominance (8). Although the clinical signs are nonspecific, in this study, algic reaction at TMJ palpation was detected in all but one dog. On CT scan, cholesteatoma showed distinctive features that should be considered almost pathognomonic: presence of an expansive and invasive unvascularized lesion involving the tympanic cavity, lytic and/or sclerotic changes of the bulla wall, and absent or minimal contrast enhancement (3–7). Moreover, TMJ sclerosis was detected in all but one dog.

To our knowledge, the otoscopic appearance of middle ear cholesteatoma has not previously been reported in dogs. During video-otoscopy, the detection of a pearly growth lesion or white/yellow scales in or protruding from the middle ear cavity should alert the clinician to the possible presence of middle ear cholesteatoma (7).

The only possible treatment for middle ear cholesteatoma is surgery, but cholesteatoma tends to recur after surgery (2,3,7). TECALBO is the most frequently performed surgical technique (2,3,5,6), whilst VBO has been suggested as the treatment of choice by Venker-Van Haagen (4), but outcomes have not been reported. Ventral bulla osteotomy may be preferable when the ear canal appears normal or mildly changed, whilst TECALBO should be selected when the owner is not dedicated to ongoing management of otitis externa or ESO is present (2,3,12,13). A combination of the 2 techniques has been performed only once (3) but could potentially decrease the incidence of recurrence because of the wider exposure of the middle ear cavity for curettage. In humans, video-assisted surgery has been reported to reduce the incidence of recurrence (14–16).

The histological diagnosis of cholesteatoma is made by the presence of the 3 components, keratin debris, the epithelium, and the subepithelial connective tissue; the presence of keratin arranged as masses or flakes is highly suggestive of an underlying cholesteatoma and final diagnosis relies on CT and surgical findings (7). In veterinary medicine, the presence of keratin alone or keratinic masses in the middle ear has been considered adequate for establishing a diagnosis of aural cholesteatoma (3,17); CT features and surgical findings in this study further supported the diagnosis of middle ear cholesteatoma. Moreover, in this study, a cholesterol granuloma was found concurrently with middle ear cholesteatoma in 4 dogs; one of these dogs had recurrent cholesteatoma but not recurrent cholesterol granuloma. Cholesterol granuloma is recognized as a complication of otitis media and may be seen in association with middle ear cholesteatoma (5,7). Microscopically, cholesterol granuloma is composed of cholesterol crystals, hemosiderin, multinucleated foreign body giant cells, and granulomatous tissue embedded in fibrous tissue with inflammatory cells, but does not contain epithelium. Hemorrhage is usually evident and plays a role in the pathogenesis. Surgery is an effective treatment (7,18,19).

Bacteria cultured from the middle ear cavity on first diagnosis and recurrence were those typically associated with otitis media (20). However, 5 samples were negative on culture (3,5); the authors could not find an explanation for the failure to recover bacteria, given the previous history of chronic otitis and the presence of middle ear disease in all dogs (20,21).

Recurrence of cholesteatoma is not a rare event and occurred in 1/4 dogs at 12 mo after surgery in 1 study and in 10/19 dogs at a mean time of 11.3 mo in another study (2,3). In this study, recurrence was suspected in 5 dogs and occurred at the mean time of 7.5 mo. A minimum follow-up time of 12 mo should be recommended. It is likely that such a high incidence of recurrence may be due to the persistence of keratin debris or the perimatrix hidden in the epitympanic recess and in the newly formed small cavities in the bulla wall detectable during surgery (2,22).

Successful management of recurrent disease with prolonged intermittent antibiotic treatment has been reported (3). Although all dogs in this study underwent medical management with broad-spectrum antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs before surgery, resolution of clinical signs after medical management occurred in only 1 dog at the second confirmed recurrence of cholesteatoma. Interestingly, the only dog that underwent CT and video-otoscopy when free of clinical signs, showed on both procedures findings suggestive of persistence of middle ear cholesteatoma. However, given the absence of clinical signs, the dog was not subjected to surgery.

In conclusion, middle ear cholesteatoma in dogs is a rare complication of chronic otitis and otitis media with a tendency to recur despite surgery. Owners should be advised that a second surgery or on-going antibiotic therapy for management of otitis media may be necessary. The use of CT scan for middle ear disease assessment can improve diagnosis of this disease, especially in light of the tomographic distinctive features of middle ear cholesteatoma. Video-assisted surgery should be further investigated in dogs. Investigation of the post-surgical tomographic aspects of the middle ear cavity in dogs treated for cholesteatoma may aid in understanding the post-surgical behavior of the disease and in detecting predictive changes for recurrence in asymptomatic patients. CVJ

Footnotes

Reprints will not be available from the authors.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Goycoolea MV, Hueb MM, Muchow D, Paparella MM. The theory of the trigger, the bridge and the transmigration in the pathogenesis of acquired cholesteatoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:244–248. doi: 10.1080/00016489950181756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little CJ, Lane JG, Gibbs C, Pearson GR. Inflammatory middle ear disease of the dog: The clinical and pathological features of cholesteatoma, a complication of otitis media. Vet Rec. 1991;128:319–322. doi: 10.1136/vr.128.14.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardie EM, Linder KE, Pease AP. Aural cholesteatoma in twenty dogs. Vet Surg. 2008;37:763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2008.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venker-Van Haagen AJ. The ear. In: Schlütersche, editor. Ear, Nose, Throat and Tracheobronchial Diseases in Dogs and Cats. 1st ed. Hannover: Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co; 2005. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson EB, Brodie HA, Breznock EM. Removal of a cholesteatoma in a dog, using a caudal auricular approach. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;211:1549–1553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacques D, Bouvy B. Un cas de cholestéatome auriculaire chez un chien traité par ablation totale du conduit auditif associée à une ostéotomie latérale de la bulle tympanique. Prad Méd Chir Anim Comp. 1999;34:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferlito A, Devaney KO, Rinaldo A, et al. Clinicopathological consultation. Ear cholesteatoma versus cholesterol granuloma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:79–85. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olszweska E, Wagner M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, et al. Etiopathogenesis of cholesteatoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:6–24. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0623-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedmann I. Epidermoid cholesteatoma and cholesterol granuloma; experimental and human. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1959;68:57–79. doi: 10.1177/000348945906800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedmann I. The comparative pathology of otitis media, experimental and human. II. The histopathology of experimental otitis of the guinea-pig with particular reference to experimental cholesteatoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1955;69:588–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persaud R, Hajioff D, Trinidade A, et al. Evidence-based review of aetiopathogenic theories of congenital and acquired cholesteatoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:1013–1019. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason LK, Harvey CE, Orsher RJ. Total ear canal ablation combined with lateral bulla osteotomy for end-stage otitis in dogs. Results in thirty dogs. Vet Surg. 1988;17:263–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1988.tb01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckman SL, Henry WB, Jr, Cechner P. Total ear canal ablation combining bulla osteotomy and curettage in dogs with chronic otitis externa and media. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;196:84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarabichi M. Endoscopic management of cholesteatoma: Long-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:874–881. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980070017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarabichi M. Endoscopic management of limited attic cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1157–1162. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajalloueyan M. Experience with surgical management of cholesteatomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:931–933. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturges BK, Dickinson PJ, Kortz GD, et al. Clinical signs, magnetic resonance imaging features, and outcome after surgical and medical treatment of otogenic intracranial infection in 11 cats and 4 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:648–656. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2006)20[648:csmrif]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox CL, Payne-Johnson CE. Aural cholesterol granuloma in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 1995;36:25–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1995.tb02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fliegner RA, Jubb KV, Lording PM. Cholesterol granuloma associated with otitis media and destruction of the tympanic bulla in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:547–549. doi: 10.1354/vp.44-4-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmeiro BS, Morris DO, Wielmet SP, Shofer FS. Evaluation of outcome of otitis media after lavage of the tympanic bulla and long-term antimicrobial drug treatment in dogs: 44 cases (1998–2002) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225:548–553. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy KM. A review of techniques for the investigation of otitis externa and otitis media. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2001;16:236–241. doi: 10.1053/svms.2001.27601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stangerup SE, Drozdziewicz D, Tos M, Hougaard-Jensen A. Recurrence of attic cholesteatoma: Different methods of estimating recurrence rates. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:283–287. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.104666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]