Abstract

Hepcidin is a peptide hormone that regulates iron homeostasis and acts as an antimicrobial peptide. It is expressed and secreted by a variety of cell types in response to iron loading and inflammation. Hepcidin mediates iron homeostasis by binding to the iron exporter ferroportin, inducing its internalization and degradation via activation of the protein kinase Jak2 and the subsequent phosphorylation of ferroportin. Here we have shown that hepcidin-activated Jak2 also phosphorylates the transcription factor Stat3, resulting in a transcriptional response. Hepcidin treatment of ferroportin-expressing mouse macrophages showed changes in mRNA expression levels of a wide variety of genes. The changes in transcript levels for half of these genes were a direct effect of hepcidin, as shown by cycloheximide insensitivity, and dependent on the presence of Stat3. Hepcidin-mediated transcriptional changes modulated LPS-induced transcription in both cultured macrophages and in vivo mouse models, as demonstrated by suppression of IL-6 and TNF-α transcript and secreted protein. Hepcidin-mediated transcription in mice also suppressed toxicity and morbidity due to single doses of LPS, poly(I:C), and turpentine, which is used to model chronic inflammatory disease. Most notably, we demonstrated that hepcidin pretreatment protected mice from a lethal dose of LPS and that hepcidin-knockout mice could be rescued from LPS toxicity by injection of hepcidin. The results of our study suggest a new function for hepcidin in modulating acute inflammatory responses.

Comment

Hepcidin is a peptide hormone primarily known as the key regulator of iron homeostasis. This peptide binds the only known cellular iron exporter, ferroportin (Fpn), leading to its internalization and degradation in hepatocytes, enterocytes, and macrophages, preventing iron transport to plasma and causing cellular retention of iron.1 Hepcidin is also an amphipathic peptide with antimicrobial activity similar to the defensin family of proteins.2 Hepcidin expression is up-regulated in response to iron stores, inflammation, and ER stress and inhibited by anemia, erythropoiesis, hypoxia, and oxidative stress.3 Other proposed factors that regulate hepcidin expression include leptin4, p535, estradiol6, and circadian rhythms6.

Hepcidin regulation in response to iron stores is mediated via the bone morphogenic protein and Sma- and Mad-related protein (BMP/SMAD) pathway and the HFE/TFR1/TFR2 complex on hepatocytes in response to plasma transferrin levels.3 In the proposed mechanism, soluble BMPs—most notably, BMP6—bind to BMP receptors and the BMP co-receptor, hemojuvelin (HJV), in response to cellular iron levels initiating the phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 and subsequent interaction with SMAD4.7, 8 This complex is then translocated to the nucleus where it binds to BMP-responsive elements (BMP-REs) within the hepcidin promoter up-regulating hepcidin expression. Recently, two new negative regulators of this pathway have been identified, SMAD7, which directly binds the hepcidin promoter to repress transcription9 and transmembrane protease serine 6 (TMPRSS6), which acts by cleaving HJV at the cell membrane to inhibit BMP signaling.10 These negative regulators may be important in limiting hepcidin production to avoid iron deficiency; mutations in TMPRSS6 are responsible for iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia.11

Hepcidin expression is also induced during infection and inflammation through activation of the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) by inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6).12 Binding of this cytokine to its cellular receptor recruits Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2) to phosphorylate STAT3 which is then translocated into the nucleus and binds to the STAT3 binding motif at −64/−72 in the hepcidin promoter region inducing hepcidin transcription.12, 13

Previously, De Domenico et al. had reported that JAK2 activation and phosphorylation of Fpn is a key step in the hepcidin-mediated internalization of Fpn.14 In the current study, these authors identified over 400 differentially expressed genes by mRNA microarray analysis in Fpn-expressing bone marrow-derived macrophages treated with hepcidin.15 Using cylclohexamide to prevent de novo protein synthesis, the authors showed that expression of approximately half of these genes was a direct result of hepcidin treatment and not due to downstream gene activation. These data also suggest a novel signal transduction role for hepcidin in mediating transcription of a large number of genes. Next, De Domenico et al. confirmed that these results were specifically due to the binding of hepcidin with Fpn by treating cells with hepcidin-20, a hepcidin derivative incapable of binding Fpn, or protegrin an antimicrobial defensin family peptide. The result of treatment with these analogs showed no effect on several genes previously up-regulated by hepcidin treatment. The role of STAT3 in this hepcidin-mediatied transcriptional response was confirmed by coimmuoprecipitation of JAK2 and STAT3 with anti-Fpn antibodies but only in the presence of hepcidin. Silencing of Fpn, JAK2, and STAT3 using siRNA pools showed that many representative high- and mid-abundance genes were affected by Fpn and JAK2 silencing, but not all of these were also affected by STAT3 silencing —three prominent examples were prostate transmembrane protein, androgen-induced 1, and matrix metallopeptidase 9. Changes in expression of these genes were also resistant to the addition of cyclohexamide, suggesting that other transcription factors in addition to STAT3 are responsive to this hepcidin/Fpn/JAK2 response.

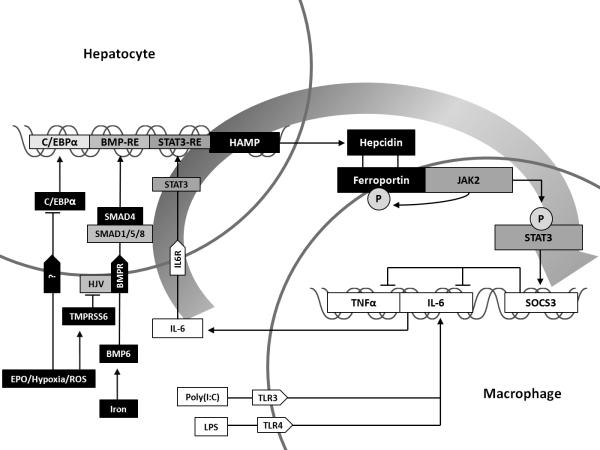

A novel finding of the current study by De Domenico et al. is the demonstration that hepcidin is involved in an Fpn/JAK2/STAT3-dependent anti-inflammatory negative feedback loop; hepcidin incubation of Fpn-expressing macrophages following LPS-induced cytokine release resulted in downregulation of IL-6 and TNFα expression (Figure 1). This effect was abolished when siRNAs were added to silence the effect of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), a known negative regulator of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. The authors suggest that this feedback mechanism may have arisen to limit the inflammatory response to bacterial infections.

Figure I. Hepcidin and STAT3 balancing iron and inflammation.

Hepcidin gene expression is up-regulated by inflammatory cytokines and iron through the JAK/STAT and BMP/SMAD pathways, respectively. It is down-regulated by erythropoietin, hypoxia, and reactive oxygen species through their modulation of C/EBPα expression and activation of TMPRSS6 which cleaves HJV. Activation of JAK2 following hepcidin binding of ferroportin results in ferroportin phosphorylation, targeting it for internalization and degradation. Hepcidin-mediated JAK2 activation also induces STAT3 phosphorylation initiating regulation of a large number of STAT3 responsive genes including SOCS3 which suppresses expression of IL-6 and TNFα, reducing further induction of HAMP expression by these inflammatory cytokines and completing a negative feedback loop.

De Domenico and colleagues also demonstrated a novel therapeutic potential for hepcidin; in vivo testing of hepcidin pretreatment on sub-lethal doses of LPS, turpentine and poly(I:C) showed reduced toxicity and morbidity. Compared to mice treated with LPS alone, hepcidin pretreated mice have lower serum and mRNA levels of both IL-6 and TNFα, higher temperatures, more energy, and better coordination. Hepcidin pretreatments also protected mice from lethal injection of LPS and the mice returned to normal function within 48 hours. However, the long-term inflammatory model of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) demonstrated that the effects of hepcidin are more likely to be effective in acute regulation rather than chronic inflammation. Though serum IL-6 levels were decreased at early timepoints, these levels rose beyond controls later in the study.

This interesting report by De Domenico et al. raises a number of additional questions to be addressed. First, this study was performed using bone marrow-derived macrophages and confirmed in peritoneal macrophages; additional studies are warranted to define the nature of the hepcidin-mediated transcriptional response in other Fpn expressing cell types. The authors noted that this response may be cell-type specific, an effect which could potentially have broad implications for iron regulation and inflammatory signaling. As mentioned above, TNFα and IL-6 were down-regulated by the expression of SOCS3 through hepcidin/Fpn STAT3-mediated pathway. Unlike IL-6, TNFα does not have a direct role in the aforementioned inflammatory mediated hepcidin up-regulation, but is often elevated in many chronic inflammatory disorders. TNFα is known to down-regulate intestinal iron absorption and induces ferritin synthesis,16 but a link to the STAT3 or SMAD4 pathways is a necessary finding for understanding hepcidin-mediated inflammatory regulation. Interferon-γ (IFNγ), an important regulator of macrophage iron homeostasis and immune function, may also provide a meaningful link, especially regarding the immune response to iron.17 Lipocalin 2 was highly up-regulated in this study and has been shown previously to be up-regulated by a deficiency in HFE.18 C/EBPα and other key factors of hepcidin expression such as upstream factors (USFs) and erythropoeisis regulators (e.g. GDF15 and TWSG1) were also not discussed in this paper. Further elaboration on these genes and others in this study could help to further the understanding of iron and inflammatory balance by STAT3.

Reference List

- 1.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, Ward DM, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004 Dec 17;306(5704):2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park CH, Valore EV, Waring AJ, Ganz T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2001 Mar 16;276(11):7806–7810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viatte L, Vaulont S. Hepcidin, the iron watcher. Biochimie. 2009 Oct;91(10):1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung B, Matak P, McKie AT, Sharp P. Leptin increases the expression of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin in HuH7 human hepatoma cells. J Nutr. 2007 Nov;137(11):2366–2370. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weizer-Stern O, Adamsky K, Margalit O, Ashur-Fabian O, Givol D, Amariglio N, et al. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism, is transcriptionally activated by p53. Br J Haematol. 2007 Jul;138(2):253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayele HK, Srai SK. Genetic variation in hepcidin expression and its implications for phenotypic differences in iron metabolism. Haematologica. 2009 Sep;94(9):1185–1188. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.010793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Samad TA, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat Genet. 2006 May;38(5):531–539. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang RH, Li C, Xu X, Zheng Y, Xiao C, Zerfas P, et al. A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2005 Dec;2(6):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mleczko-Sanecka K, Casanovas G, Ragab A, Breitkopf K, Muller A, Boutros M, et al. SMAD7 controls iron metabolism as a potent inhibitor of hepcidin expression. Blood. 2010 Apr 1;115(13):2657–2665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-238105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silvestri L, Pagani A, Nai A, De Domenico I, Kaplan J, Camaschella C. The serine protease matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6) inhibits hepcidin activation by cleaving membrane hemojuvelin. Cell Metab. 2008 Dec;8(6):502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finberg KE, Heeney MM, Campagna DR, Aydinok Y, Pearson HA, Hartman KR, et al. Mutations in TMPRSS6 cause iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) Nat Genet. 2008 May;40(5):569–571. doi: 10.1038/ng.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood. 2006 Nov 1;108(9):3204–3209. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falzacappa MV Verga, Vujic SM, Kessler R, Stolte J, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood. 2007 Jan 1;109(1):353–358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Domenico I, Ward DM, Langelier C, Vaughn MB, Nemeth E, Sundquist WI, et al. The molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin down-regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007 Jul;18(7):2569–2578. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Domenico I, Zhang TY, Koening CL, Branch RW, London N, Lo E, et al. Hepcidin mediates transcriptional changes that modulate acute cytokine-induced inflammatory responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010 Jul 1;120(7):2395–2405. doi: 10.1172/JCI42011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma N, Laftah AH, Brookes MJ, Cooper B, Iqbal T, Tselepis C. A role for tumour necrosis factor alpha in human small bowel iron transport. Biochem J. 2005 Sep 1;390(Pt 2):437–446. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oexle H, Kaser A, Most J, Bellmann-Weiler R, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, et al. Pathways for the regulation of interferon-gamma-inducible genes by iron in human monocytic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003 Aug;74(2):287–294. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0802420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nairz M, Theurl I, Schroll A, Theurl M, Fritsche G, Lindner E, et al. Absence of functional Hfe protects mice from invasive Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection via induction of lipocalin-2. Blood. 2009 Oct 22;114(17):3642–3651. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]