Abstract

PAI-1 has been shown to be both profibrotic and antifibrotic in animal models of hepatic fibrosis. Although these models have similarities to human fibrotic liver disease, no rodent model completely recapitulates the clinical situation; indeed, transaminase values in most models of hepatic fibrosis are much higher than in chronic liver diseases in humans. Here, wild-type and PAI-1−/− mice were administered AngII (500 ng/kg/min) for 4 weeks. ECM accumulation was evaluated by Sirius red staining, hydroxyproline content, and fibrin and collagen immunostaining. Induction of pro-fibrotic genes was assessed by real-time RT-PCR. Despite the absence of any significant liver damage, AngII infusion increased the deposition of hepatic collagen and fibrin ECM, with a perisinusoidal pattern. PAI-1−/− mice were protected from these ECM changes, indicating a causal role of PAI-1 in this fibrosis model. Protection in the knockout strain correlated with a blunted increase in αSMA, and elevated activities of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2, MMP9). These data suggest that PAI-1 plays a critical role in mediating fibrosis caused by AngII and lends weight-of-evidence to a pro-fibrotic role of this protein in liver. Furthermore, the current study proposes a new model of 'pure' hepatic fibrosis in mice with little inflammation or hepatocyte death.

Keywords: renin-angiotensin system, fibrin, mouse, knockout

Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis is the culmination of wound-healing in the liver in response to repeated injury [1]. After liver injury, parenchymal cells can regenerate and replace the necrotic or apoptotic cells. However, this regenerative response can incompletely compensate for chronic liver injury. Under such conditions, extracellular matrices (ECM) can be deposited in damaged areas, leading to fibrosis/cirrhosis [2]. The mechanisms that lead to fibrosis are not completely understood. To achieve a targeted therapy for hepatic fibrosis, a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms is necessary.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a key regulator of blood pressure homeostasis, as well as fluid and sodium balance in mammals through coordinated effects on heart, vessels and kidneys. The RAS also plays a major role in wound healing and remodeling, independent of its role on blood pressure regulation [3]. Similar to other organs, recent evidence indicates that the RAS is also involved in liver remodeling during fibrogenesis [4]. Specifically, AngII has been shown to be an important mediator in liver fibrosis, and to stimulate the synthesis of ECM [5–9], via hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation [6].

Previous studies have shown that AngII is a potent inducer of PAI-1 [10]. PAI-1 is a major inhibitor of both tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and is therefore a key regulator of fibrinolysis by plasmin [11]. In addition to regulating the accumulation of fibrinogen/fibrin in the extracellular space, plasmin can also directly degrade other ECM components, such as laminin, proteoglycan, and type IV collagen [12–14]. Furthermore, plasmin can also indirectly degrade ECM via activation of MMPs(e.g., MMP3 and MMP9 [15]). PAI-1 is known to be induced in models of hepatic fibrosis [16, 17].

PAI-1 is also directly produced by hepatic stellate cells, the major cell-type responsible for ECM accumulation during fibrosis [18]. Recently it has been shown in a bile duct ligation model (BDL) that PAI-1 contributes to fibrogenesis in liver [19]. However, results with the CCl4 model demonstrated an apparent profibrotic role of PAI-1 in mouse liver [20]. Reasons for the discrepancies between these models remain unclear, but emphasize the need for weight-of-evidence regarding the role of PAI-1 in hepatic fibrogenesis. The purpose of the current study was to determine if PAI-1 plays a critical role in a model of AngII-induced hepatic fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatments

Eight week old male C57BL/6J and PAI-1 knockout (B6.129S2-Serpine1tm1Mlg/J: PAI-1−/−) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All knockout mice used in this study were backcrossed at least 10 times onto C57BL/6J, avoiding concerns regarding differences between the strains at nonspecific loci. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and procedures were approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Food and tap water were allowed ad libitum. Wild-type and PAI-1−/− mice were administered angiotensin II (AngII; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA; ~500 ng/kg/min s.c.) via osmotic pumps (Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) surgically implanted in the dorsal area of the mice analogous to previously published studies in rat [5]. Controls underwent full surgery and received inserts not containing AngII. For sacrifice, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100/15 mg/kg i.m.) 4 weeks after surgery. Blood was collected from the vena cava just prior to sacrifice by exsanguination, and citrated plasma was stored at −80°C for further analysis. Portions of liver tissue were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, while others were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin or embedded in frozen specimen medium (Tissue-Tek OCT compound, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) for subsequent sectioning and mounting on microscope slides.

Biochemical analyses and histology

Plasma levels of aminotransferases (ALT) were determined using commercially available kits (Thermotrace, Melbourne, Australia) [21]. Levels of TNFα and TIMP-1 protein were determined using ELISA kits purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Levels of PAI-1 protein were determined using an ELISA kit purchased from Molecular Innovations (Novi, MI). Plasma levels of HGF were determined using an ELISA kit purchased from B-Bridge International, Inc. (Mountain View, CA). Pathology was scored in a blinded manner by a trained pathologist [21]. The intensity and extent of Sirius Red staining in liver tissues were quantified by image analysis using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), which was performed using techniques described previously [19]. The accumulation of fibrin matrices was determined immunofluorometrically, as described previously [21]. Hydroxyproline content was quantitated colorimetrically from liver samples using the chloramine T method as described by Ellis et al. [22] with minor modifications [19]. The activity of tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) were determined in liver and plasma samples as described by Bezerra et al [23], with minor modifications [19]. The activity of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 were determined in liver samples as described by Bergheim et al. [19].

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescent detection of collagen type I, frozen sections of liver, were blocked with PBS containing 2% goat serum, 5% BSA, 0.1% cold fish skin gelatin, 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 0.05% Tween 20 for 30 min, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with collagen Type I (Meridian Life Science, Saco, ME) or CD31 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) antibodies in blocking solution. Sections were washed with PBS and incubated for 2 h with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were washed with PBS and mounted with mounting medium containing 1.5 µg/ml DAPI (VECTASHIELD w/DAPI; Vectastain, Torrance,CA).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time RT-PCR

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR was performed as described previously [24]. PCR primers and probes were designed using Primer 3 software (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA). Primers were designed to cross introns to ensure that only cDNA and not genomic DNA was amplified (see table 1 for sequences). Prolyl 4-hydroxylase α (P4Hα), F4/80, CD31, Tie2, TIMP2 and TGFβ primers and probes were ordered as commercially available kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The comparative CT method was used to determine fold differences between samples and the calibrator gene (β-actin) and purity of PCR products was verified by gel electrophoresis. The comparative CT method determines the amount of target, normalized to an endogenous reference (β-actin) and relative to a calibrator (2−ΔΔCt).

Table 1.

Sequences of primers and probes generated for real-time RT-PCR detection of expression

| Forward (3’–5’) | Reverse(3’–5’) | Probe(3’–5’) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAI-1 | CACCAACATTTTGGACGCTGA | TCAGTCATGCCCAGCTTCTCC | CCAGGCTGCCCCGCCTCCTC |

| β-actin | GGCTCCCAGCACCATGAA | AGCCACCGATCCACACAGA | AAGATCATTGCTCCTCCTGAGCGCAAGTA |

| αSMA | TGCCATCATGCGTCTGGACT | GCCGTGGCCATCTCATTTTC | TGCCGAGCGTGAGATTGTCCGTGA |

| Collagen Iα1 | GTCTTCCTGGCCCCTCTGGT | AGCAGGGCCAGTCTCACCAC | CCCCATGGGGCCCCCTGGAT |

| TIMP1 | CCCACCCACAGACAGCCTTC | CGGCCCGTGATGAGAAACTC | TGCCCACAAGTCCCAGAACCGCA |

| Angiotensinogen | AAAGAACCCGCCTCCTCG | TTGTAGGATCCCCGAATTTCC | ATCCGTCTGACCCTG |

| AT1R | CCATTGTCCACCCGATGAAG | TGCAGGTGACTTTGGCCAC | CTCGCCTCCGCCGCACGA |

| ACE | TGAGAAAAGCACGGAGGTATCC | AGAGTTTTGAAAGTTGCTCACATC | ACCCTGAAATATGGCACCCGGGC |

Statistical analyses

Results are reported as means ± SEM (n = 4–7). ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test (for parametric data) or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test (for nonparametric data) was used for the determination of statistical significance among treatment groups, as appropriate. A p value less than 0.05 was selected before the study as the level of significance.

Results

PAI-1 deficient mice are protected from liver fibrosis caused by AngII

Growth rates in mice infused with saline were normal, with values of 0.7 ± 0.1 grams/wk; AngII infusion did not significantly alter growth rates in either wild-type or PAI-1−/− mice (Table 2). There were no detectable gross morphologic changes observed in liver tissue after AngII administration in wild-type mice (Figure 1 and Table 2); pathology scores in this group for inflammation and necrosis were not significantly different from saline-infused mice (Table 2). Knocking out PAI-1 also had no apparent effect on these results (Table 2). AngII did not significantly increase plasma ALT values in either wild-type or knockout mice (Table 2). AngII infusion did significantly increase liver weight ~20% in wild-type mice (Table 2); this effect of AngII was not altered in PAI-1−/− mice.

Table 2.

Routine parameters

| saline | AngII | AngII + PAI-1−/− |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth(BW)/week | 0.7±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.7±0. |

| Path. Scores | |||

| Inflammation | 0.0±0.0 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.2±0.2 |

| Necrosis | 0.0±0.0 | 0.3±0.3 | 0.0±0.0 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 20±1 | 29±4 | 33±8 |

| LW (% of BW) | 4.5±0.2 | 5.3±0.1a | 5.2±0.2a |

Animals and treatments are described in Materials and Methods. Data are means ± S.E.M. (n = 4–6) and are reported as indicated in the individual rows.

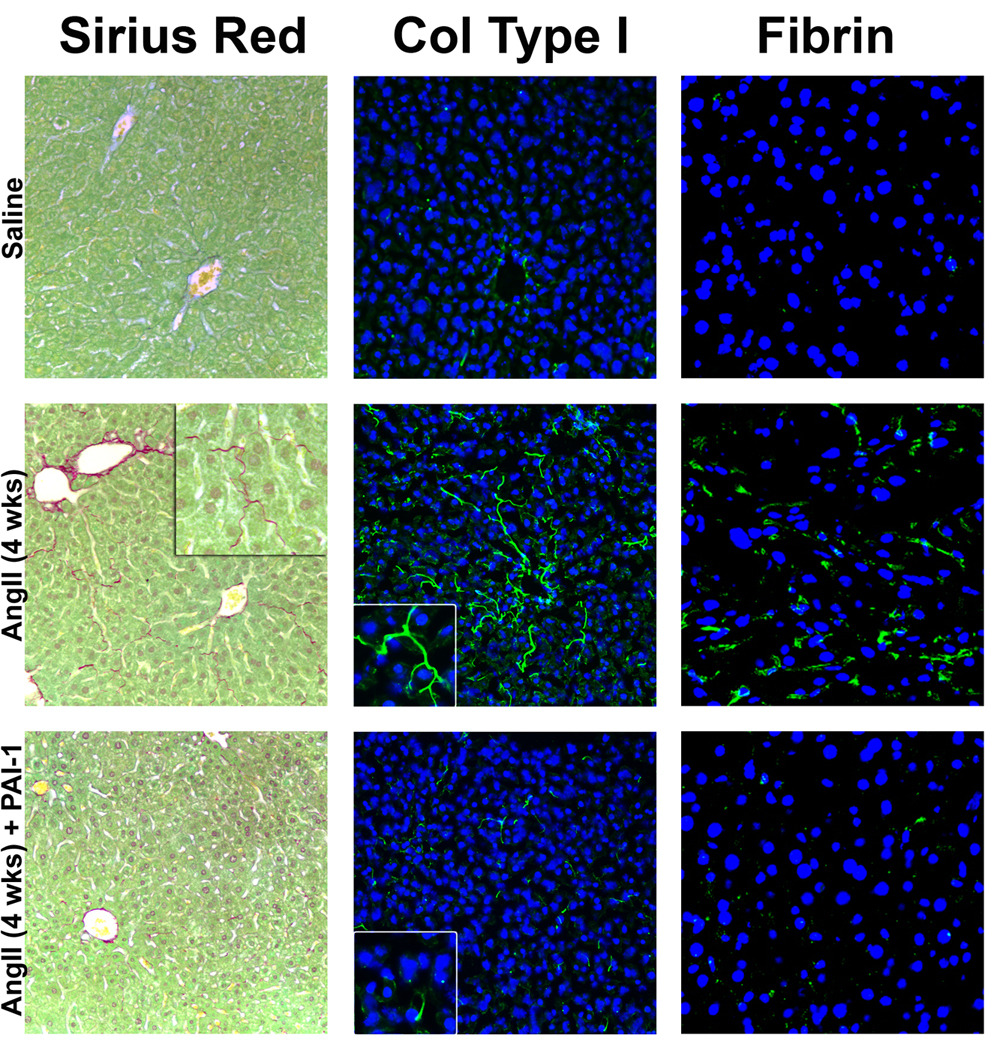

Figure 1. Photomicrographs of livers after 4 weeks of AngII administration.

Mice were treated as described in Materials and Methods. Representative photomicrographs of Sirius Red (200×, inset 400× left) and immunofluorescent collagen type I (Col type I, 200×, insets 400× middle) stains are shown. For immunofluorescent detection of hepatic fibrin (green) against a blue nuclear stain (400×, right), representative confocal photomicrographs are shown.

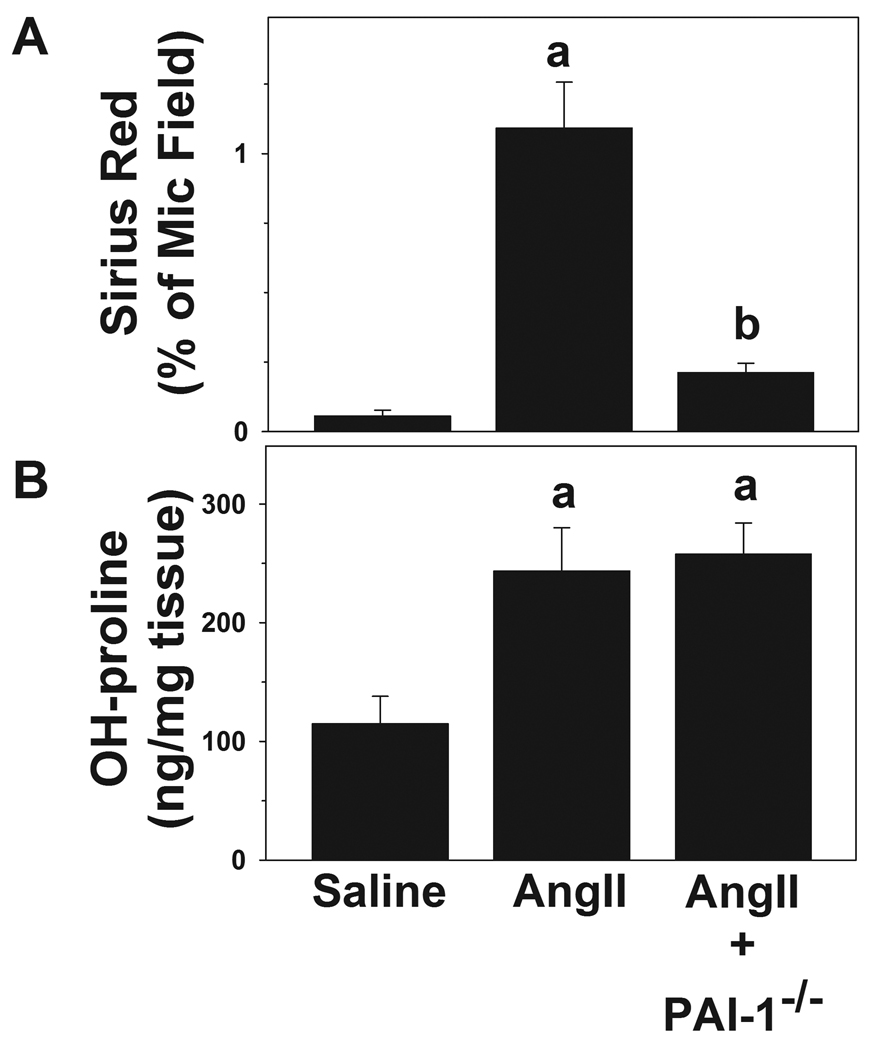

Although AngII infusion caused no detectable changes in histologic and plasma indices of hepatic injury and inflammation (Table 2), it significantly increased the deposition of fine Sirius red-positive fibers (Figure 1, left column) in the sinusoids of the liver lobule (i.e., perisinusoidal fibrosis) with values ~6-fold higher than controls (Figure 2A). PAI-1−/− mice were protected from this effect of AngII (Figure 1, lower left panel), blunting the increase in Sirius red staining caused by AngII by over 75% (Figure 2A). Hepatic hydroxyproline content was significantly increased by AngII (~2-fold) in both wt and in PAI-1−/− mice (Figure 2B). Although Sirius red staining is indicative of collagen fibers, it is not necessarily specific for collagen fibers associated with hepatic fibrosis (i.e., type I collagen). To validate the accumulation of type I collagen fibers after AngII infusion, collagen type I protein was detected via immunofluorescence (Figure 1, center panel). Collagen type I fibers (Figure 1, center column) were detected in the sinusoids, analogous to the Sirius red staining (Figure 1, left column). PAI-1−/− mice were protected from this effect of AngII (Figure 1, lower middle panel). Hepatic fibrosis includes the accumulation of not only collagen ECM, but also other matrices [25]. PAI-1 is known to play a key role in the regulation of fibrin ECM. The effect of AngII on fibrin accumulation was therefore determined (Figure 1, right column). In wild-type mice, chronic AngII infusion caused fibrin to accumulate in sinusoidal spaces of the liver lobule (Figure 1, right middle panel). PAI-1−/− mice were protected from this effect of AngII (Figure 1, right bottom panel).

Figure 2. Effect AngII on indices of hepatic fibrosis in liver.

Mice were treated as described in Materials and Methods. Image analysis of Sirius Red positive staining (A) and colorimetric quantitation of hydroxyproline (OH-pro) content in liver tissue (B) are shown. Quantitative data are means ± SEM (n= 4–7) and are expressed as % of microscope field for Sirius Red and as µg/mg tissue for hydroxyproline. a, p < 0.05 compared to saline; b, p < 0.05 compared to wild-type animals + AngII.

Effect of AngII on key indices of inflammation and fibrosis in wt and PAI-1−/− mice

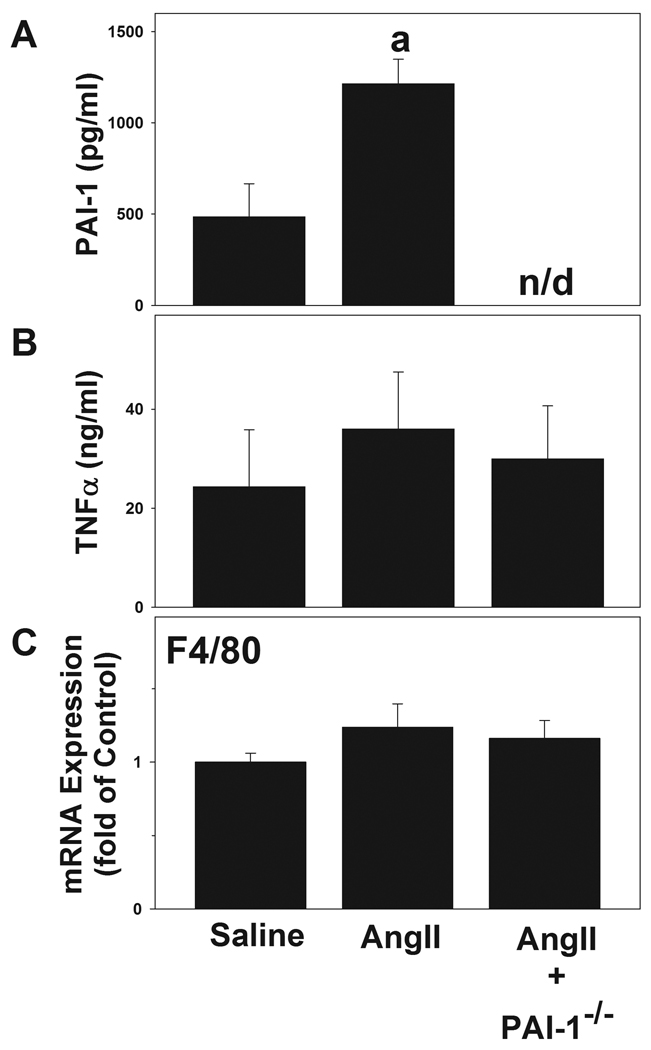

The effect of AngII on hepatic expression of key genes of the RAS (angiotensinogen, AT1R and ACE) was determined in samples from wild-type and PAI-1−/− mice via real-time RT-PCR. There was no significant effect of AngII administration on angiotensinogen (1.3 ± 0.3 fold over saline) and AT1R (0.9 ± 0.2 fold) expression in wild-type mice. The expression of ACE was significantly increased (2.7 ± 0.5 fold) by AngII infusion in wild-type mice. This effect of AngII infusion was not significantly altered in PAI-1−/− mice compared to wild-types. It has been shown previously that acute phase proteins like PAI-1 and TNFα are elevated in rats after exposure to AngII [5, 26]. In line with previous studies in the rat, AngII infusion significantly elevated plasma levels of PAI-1 (Figure 3A). However, in contrast to results in rats, no changes in circulating TNFα protein levels were observed after treatment with AngII either in the wild-type or in PAI-1 deficient mice (Figure 3B). Circulating levels of HGF protein in saline-infused animals were normal (188 ± 29 pg/ml); this variable was not significantly altered by AngII infusion. Expression of the Kupffer cell marker F4/80 increases with the activation of macrophages [27]. No increase F4/80 expression was noted after AngII administration (Figure 3C). Similar results were observed with immunohistochemical detection of F4/80 in liver tissue (data not shown).

Figure 3. Effect of AngII on indices of hepatic inflammation.

Mice were treated as described in Materials and Methods. Panels A and B depict results for circulating levels of PAI-1 and TNFα in plasma. Panel C shows hepatic mRNA expression of F4/80. Quantitative data are means ± SEM (n = 4–7) and are expressed as pg/ml or ng/ml plasma for PAI-1 and TNFα respectively and as fold of control for F4/80 expression. a, p < 0.05 compared to saline; b, p < 0.05 compared to wild-type animals + AngII.

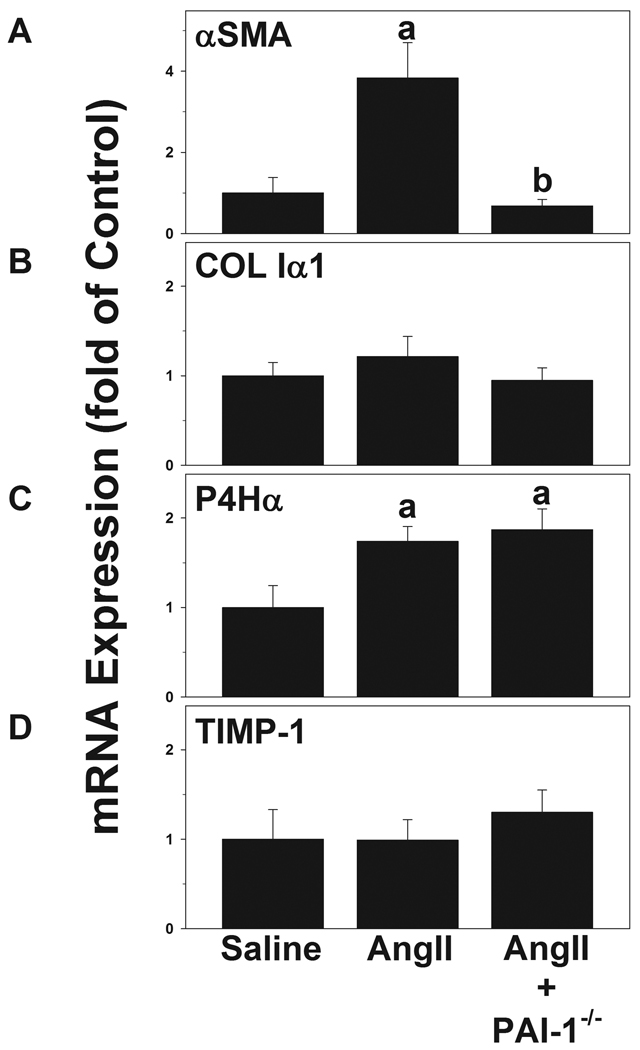

The effect of AngII on hepatic expression of key pro-fibrotic genes was determined in samples from wild-type and PAI-1−/− mice via real-time RT-PCR (Figure 4). Increases in the expression of αSMA and collagen Iα1 are indicative of stellate cell activation and de novo collagen synthesis in the liver, respectively. In addition to de novo synthesis, collagen ECM accumulation is also regulated at the level of post-translational modification by prolyl 4-hydroxylase and by the inhibition of ECM degradation by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). The expression of the alpha chain of prolyl 4-hydroxylase (P4Hα) and the major inhibitor of collagenases (TIMP-1) [28], was therefore also determined by real-time RT-PCR. Here, AngII significantly induced the hepatic expression of αSMA and P4Hα in wild-type mice, while not affecting hepatic mRNA expression of collagen Iα1 or TIMP1 (Figure 4). TIMP-1 protein, as determined by ELISA, was also unaffected by AngII infusion under these conditions (data not shown). In PAI-1−/− mice, the increase in αSMA expression caused by AngII was completely attenuated, but the increase in P4Hα was unchanged (Figure 4). Levels of TGFβ and TIMP-2 mRNA expression were also unaffected by AngII infusion or by knocking out PAI-1 (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effect of angiotensin on the expression of pro-fibrotic genes.

Mice were treated and Real-time RT-PCR for αSMA (A), COL Iα1 (B), P4Hα (C) and TIMP-1 (D) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Quantitative data are means ± SEM (n = 4–7) and are expressed as fold of control. a, p < 0.05 compared to saline; b, p < 0.05 compared to wild-type animals + AngII.

Effect of AngII on ECM metabolism and angiogenesis in wt and PAI-1−/− mice

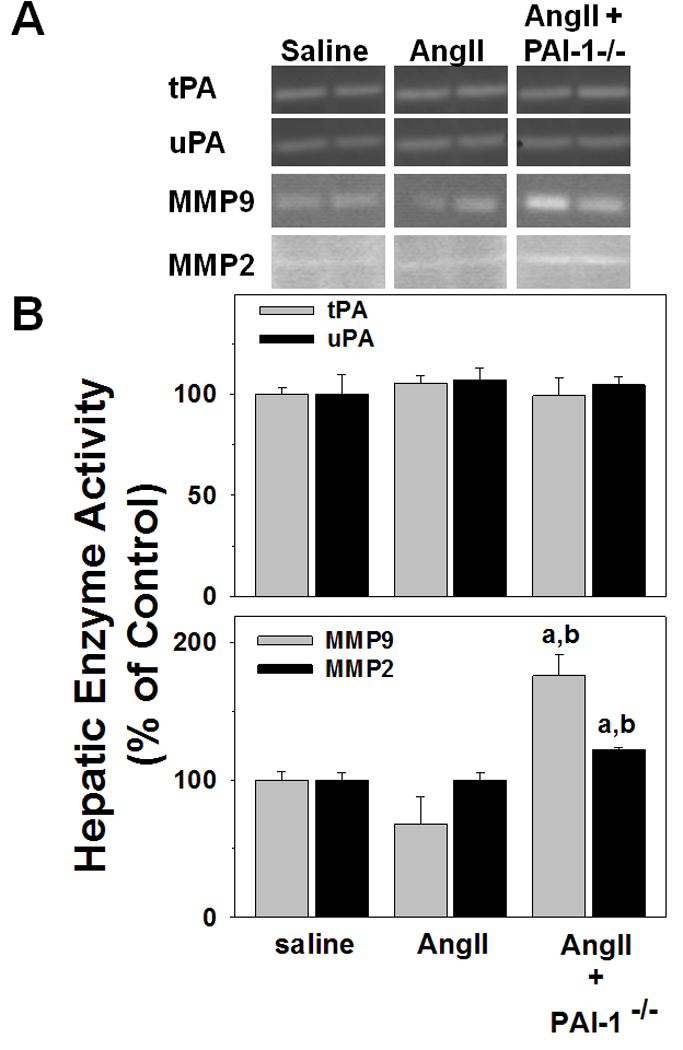

PAI-1 is a major inhibitor of both uPA and tPA, which in turn activate MMPs via plasmin [11, 15]. Changes in MMP activity may also alter ECM accumulation. The effect of AngII on the activity of uPA/tPA as well as MMP9 and MMP2 in livers was therefore determined by zymography. Figure 5 depicts representative zymograms (Panel A) and densitometric analysis (Panel B). AngII did not significantly affect the zymographic activity of any of these enzymes in wild-type mice (Figure 5). In contrast, MMP2 and MMP9 activities were significantly increased in PAI-1−/− mice exposed to AngII (Figure 5). AngII has been shown in previous studies to promote angiogenesis in endothelial cells [29]. Accordingly, the effect of AngII on the expression of known indices of angiogenesis (CD31 and Tie2) were determined. Figure 6 depicts representative photomicrographs of immunofluorescent CD31 detection (Panel A) and quantitative analysis of hepatic CD31 and Tie2 mRNA expression (Panel B). AngII significantly increased CD31 staining and CD31 and Tie2 mRNA expression in liver. In PAI-1−/− mice, this increase in markers of angiogenesis caused by AngII was significantly blunted.

Figure 5. Hepatic uPA/tPA and MMP activity after AngII.

Mice were treated and zymography was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Panel A shows representative zymography bands from the same gel, while Panel B depicts respective summary results of image analysis of gelatinase activity. Quantitative data are means ± SEM (n = 4–7) and are expressed as fold of control. a, p < 0.05 compared to saline; b, p < 0.05 compared to wild-type animals + AngII.

Figure 6. Effect of AngII on markers of angiogenesis.

Mice were treated and Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Panel A: Representative confocal photomicrographs (400×) depicting immunofluorescent detection of hepatic CD31 against a DAPI nuclear stain are shown. Panel B: Real-time RT-PCR for CD31 and Tie2. Quantitative data are means ± SEM (n = 4–7) and are expressed as fold of control. a, p < 0.05 compared to saline; b, p < 0.05 compared to wild-type animals + AngII.

Discussion

AngII is generated from its precursors by endothelial cells, followed by proteolytic activation by circulating angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). As mentioned in the Introduction, AngII is a classic endocrine hormone that plays a central role in the regulation of blood pressure and sodium homeostasis [30]. AngII is also known to have a number of blood pressure-independent actions including mitogenic and trophic effects on cell growth [31]. Indeed, the profound cardioprotection observed with RAS inhibitors in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study appeared to be mediated more by direct prevention of cardiac remodeling than by their antipressor effects [32, 33]. Recent in vivo studies have also demonstrated that the RAS may be involved in fibrotic (i.e. remodeling) responses in other organs, including liver [4]. For example, it has been shown in a recent study that gain-of-function polymorphisms in the AGTR1 gene increase the risk of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [34]. However, the mechanisms by which AngII mediates hepatic fibrogenesis are incompletely understood. As discussed below, most models of AngII-mediated hepatic fibrosis involve both inflammation and fibrosis, which blurs the relative direct versus indirect (i.e., via inflammation) roles of AngII.

A basic limitation in fibrotic liver disease research is that no rodent model completely recapitulates the human disease. Indeed, rodents appear to be more resistant to hepatic fibrosis than humans. Thus, surrogate models of hepatic fibrosis (e.g., BDL and CCl4) are predominantly used. Whereas these models have many similarities to the human disease, there are also differences. Specifically, liver fibrosis in these animal models is accompanied by liver damage and inflammation that is far more severe than usually observed in human fibrotic diseases [19]. Indeed, chronic liver diseases in humans are generally associated with low (or even subclinical) elevations in transaminases [35]. In contrast, transaminases in the BDL and CCl4 models of fibrosis are generally >10-fold higher than in controls [19, 20]. Multiple models of liver fibrosis should therefore be employed to offer weight-of-evidence on potential mechanisms of action.

It has been shown in a previous model of BDL-induced hepatic fibrosis that knocking out PAI-1 protected from ECM accumulation and subsequent fibrosis [19]. In contrast, knocking out PAI-1 exacerbated liver damage in the CCl4 model [20]. The latter finding appears to be secondary to a role of PAI-1 in hepatic regeneration [20]. However, as mentioned above, liver damage in both models is more severe than generally seen in human fibrotic liver diseases. Here, the effect of knocking out PAI-1 in a less severe mouse model of fibrosis was investigated. Infusion of AngII in the current study caused mild perisinusoidal fibrosis in wild-type mice (Figure 1), more similar to early stages in humans, without causing any significant inflammation and hepatocellular death (Figures 1 – 3, Table 2). In most animal models of fibrosis, there is at least a detectable increase in hepatic inflammation [5, 36]. However, whether inflammation is required for fibrosis remains unclear, as some fibrotic diseases (e.g., hemachromatosis) do not possess a significant detectable inflammatory component (see Friedman [25] for review). These data here suggest an almost exclusive profibrotic role of AngII in the current model.

An increased accumulation of extracellular matrices can lead to fibrosis of the liver. However, these matrices not only include collagen, but also other components, including fibrin. In this model, it has been shown that AngII causes not only collagen to accumulate in mouse liver, but also fibrin ECM (Figure 1). PAI-1 is a major inhibitor of both tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and is therefore a key regulator of fibrinolysis by plasmin. In addition to regulating the accumulation of fibrinogen/fibrin in the extracellular space, plasmin can also directly degrade other ECM components such as laminin, proteoglycan, and type IV collagen. Plasmin can also indirectly degrade ECM via activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Thus, by impairing the plasminogen activating systems, PAI-1 can alter organ fibrogenesis.

A major source of regulation of hepatic fibrosis is the activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (HSC) and production of ECM by these cells. Key indicators of HSC activation are increases in expression levels of αSMA and collagen Iα1. However, as demonstrated in dual αSMA-RFP and collagen-EGFP reporter mice [37], these 2 genes are not always coexpressed in activated HSCs. Previous studies in rats have shown that AngII infusion can activate HSC [5], as well as enhance ECM synthesis caused by BDL [6]. Here, AngII infusion increased αSMA expression, but did not affect collagen Iα1 expression (Figure 4). These results indicate that AngII infusion did not cause hepatic fibrosis under these conditions by increasing de novo synthesis of collagen mRNA.

As mentioned in the Results section, de novo synthesis is not the sole mechanism by which collagen ECM accumulation is regulated [38]. Another point of regulation is post-translational modification by prolyl-4-hydroxylases; this step is critical for the stability of the collagen ECM triple helix [39]. AngII infusion significantly increased the expression of P4Hα, a key subunit for prolyl-4-hydroxylase (Figure 4), and also increased hydroxyproline content (Figure 2). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that AngII increased collagen deposition under these conditions, not via de novo synthesis, but rather by increasing proline hydroxylation. This working hypothesis is in line with published studies in other organs. For example, Ju et al. [40] showed that AT1 receptor blockade protected against collagen ECM accumulation in a model of post-myocardial infarction heart fibrosis. This protective effect was not mediated by blunting the increase in collagen mRNA expression, but rather by blocking the increase in prolyl hydroxylation of collagen protein [40].

Although AngII infusion likely increased collagen ECM by increasing the rate at which collagen is cross-linked into triple helices by prolyl-4-hydroxylase, the protective effect of knocking out PAI-1 cannot be explained by altering this effect of AngII. Specifically, although knocking-out PAI-1 blunted the accumulation of collagen fibers, it had no effect on the increase in P4Hα expression (Figure 4) or on hydroxyproline content caused by AngII (Figure 2). This apparent disconnect between Sirius red staining and proline hydroxylation potentially sheds light on the mechanism of protection in PAI-1 knockout mice under these conditions. The lack of difference between the two strains on this variable suggests that the major mechanism of protection in the PAI-1−/− mice was downstream from cross-linking and deposition of the collagen fibers.

In addition to regulating the synthesis (de novo expression) and deposition (proline hydroxylation) of ECM, hepatic collagen fibrogenesis is also regulated at the level of degradation of ECM. This latter effect is mediated by the balance between enzymes that trigger ECM degradation (e.g., MMPs) and their inhibitors (e.g., TIMPs [41]). As mentioned in the Introduction, inhibiting PAI-1 can indirectly increase MMP activity. Indeed, there was a significant increase in hepatic MMP9 and MMP2 activities in PAI-1−/− mice after AngII infusion (Figure 5) without affecting TIMP1 mRNA (Figure 4), suggesting that blocking PAI-1 favored ECM degradation after AngII infusion. Furthermore, although collagen I is the major ECM component that accumulates during fibrosis, various other forms of ECM (e.g., fibrin, laminin etc) also build up in hepatic fibrogenesis [41]. Here, AngII infusion also increased the accumulation of extracellular fibrin ECM in the liver, an effect which was blocked in PAI-1−/− mice (Figure 1, right panel). These results are in line with previous studies in PAI-1−/− in a BDL model of hepatic fibrosis [19].

Angiogenesis and fibrosis are often concomitant events in liver pathology, and may be mechanistically-linked processes. Excessive ECM during fibrosis may increase hepatic resistance to blood flow, which can result in downstream tissue hypoxia. The hypoxia in turn may increase angiogenic factors and induce neovessel formation to recruit inflammatory and profibrogenic cells, which then further develop fibrogenesis. The RAS has also been implicated in angiogenesis (see [42] for review). Here, AngII infusion increased indices of angiogenesis (Figure 6), and this effect was completely attenuated in PAI-1 knockout mice. Previous work has shown that PAI-1 is proangiogenic under some conditions [43]. The results herein suggest that AngII-induced angiogenesis is dependent on PAI-1 induction. This effect of knocking out PAI-1 may also contribute to the antifibrotic effect observed under these conditions.

Summary and Conclusions

Taken together, the results of this study indicate that PAI-1 is involved in AngII-induced hepatic fibrosis. Blocking the activation of HSC and an increase in MMP activation in PAI-1 knockout mice most likely plays an important role in this mechanism. Previous studies have shown that PAI-1 has both a proinflammatory (e.g., [24]) and profibrotic (e.g., [19]) role in liver. However, as most models of hepatic fibrosis also increase inflammation, whether the profibrotic role of PAI-1 is secondary to its proinflammatory role remained unclear. ECM accumulation in the current model appears to be independent of robust liver injury and inflammation. The results of this study therefore support the hypothesis that PAI-1 is profibrotic in liver independent of its effect on liver damage. Since hypertension is an independent risk factor for hepatic fibrogenesis in several diseases (e.g., NAFLD [44]), mechanisms by which AngII exacerbates the development of fibrogenesis in other models may be of interest. This model may also be useful as a less severe model of human fibrotic liver disease.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA003624). JPK was supported by a predoctoral (F31) fellowship from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA017346) and JIB was supported by a postdoctoral (T32) fellowship from National Institute of Environmental Health Science (ES011564).

Abbreviations

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- AngII

angiotensin II

- ECM

extracellular matrices

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- H&E

hematoxylin & eosin

- αSMA

alpha-smooth muscle actin

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Juliane I. Beier, Email: juliane.beier@louisville.edu.

J Phillip Kaiser, Email: jpkais01@louisville.edu.

Luping Guo, Email: l0guo01@louisville.edu.

Manuel Martínez-Maldonado, Email: gene3m@gmail.com.

Gavin E. Arteel, Email: gavin.arteel@louisville.edu.

Reference List

- 1.Friedman SL. J. Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. S38–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bataller R, Brenner DA. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mezzano SA, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Hypertension. 2001;38:635–638. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.094234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson JR, Clouston AD, Ando Y, Kelemen LI, Horn MJ, Adamson MD, Purdie DM, Powell EE. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:148–155. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bataller R, Gabele E, Schoonhoven R, Morris T, Lehnert M, Yang L, Brenner DA, Rippe RA. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G642–G651. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00037.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bataller R, Schwabe RF, Choi YH, Yang L, Paik YH, Lindquist J, Qian T, Schoonhoven R, Hagedorn CH, Lemasters JJ, Brenner DA. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1383–1394. doi: 10.1172/JCI18212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bataller R, Gabele E, Parsons CJ, Morris T, Yang L, Schoonhoven R, Brenner DA, Rippe RA. Hepatology. 2005;41:1046–1055. doi: 10.1002/hep.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katwa LC, Campbell SE, Tyagi SC, Lee SJ, Cicila GT, Weber KT. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1375–1386. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall RP, McAnulty RJ, Laurent GJ. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1999–2004. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9907004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown NJ, Vaughan DE. Adv. Intern. Med. 2000;45:419–429. 419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruithof EK. Enzyme. 1988;40:113–121. doi: 10.1159/000469153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liotta LA, Goldfarb RH, Brundage R, Siegal GP, Terranova V, Garbisa S. Cancer Res. 1981;41:4629–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mochan E, Keler T. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;800:312–315. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(84)90412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackay AR, Corbitt RH, Hartzler JL, Thorgeirsson UP. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5997–6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos-DeSimone N, Hahn-Dantona E, Sipley J, Nagase H, French DL, Quigley JP. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13066–13076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang LP, Takahara T, Yata Y, Furui K, Jin B, Kawada N, Watanabe A. J. Hepatol. 1999;31:703–711. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bueno MR, Daneri A, Armendariz-Borunda J. J. Hepatol. 2000;33:915–925. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyland H, Gentry J, Arthur MJ, Benyon RC. Hepatology. 1996;24:1172–1178. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergheim I, Guo L, Davis MA, Duveau I, Arteel GE. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;316:592–600. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Montfort C, Beier JI, Kaiser JP, Guo L, Joshi-Barve S, Pritchard MT, States JC, Arteel GE. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G657–G666. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00107.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beier JI, Guo L, von Montfort C, Kaiser JP, Joshi-Barve S, Arteel GE. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;325:801–808. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136721.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis AJ, Curry VA, Powell EK, Cawston TE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;201:94–101. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bezerra JA, Currier AR, Melin-Aldana H, Sabla G, Bugge TH, Kombrinck KW, Degen JL. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:921–929. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64039-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beier JI, Luyendyk JP, Guo L, von Montfort C, Staunton DE, Arteel GE. Hepatology. 2009;49:1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/hep.22847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman SL. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feener EP, Northrup JM, Aiello LP, King GL. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:1353–1362. doi: 10.1172/JCI117786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fickert P, Thueringer A, Moustafa T, Silbert D, Gumhold J, Tsybrovskyy O, Lebofsky M, Jaeschke H, Denk H, Trauner M. Lab Invest. 2010;90:844–852. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsons CJ, Bradford BU, Pan CQ, Cheung E, Schauer M, Knorr A, Krebs B, Kraft S, Zahn S, Brocks B, Feirt N, Mei B, Cho MS, Ramamoorthi R, Roldan G, Ng P, Lum P, Hirth-Dietrich C, Tomkinson A, Brenner DA. Hepatology. 2004;40:1106–1115. doi: 10.1002/hep.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otani A, Takagi H, Suzuma K, Honda Y. Circ. Res. 1998;82:619–628. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavras I, Gavras H. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2002;16 Suppl 2:S2–S6. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001392. S2–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes AD. J. Renin. Angiotensin. Aldosterone. Syst. 2000;1:125–130. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sleight P, Yusuf S, Pogue J, Tsuyuki R, Diaz R, Probstfield J. Lancet. 2001;358:2130–2131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arteel GE. Hepatology. 2004;40:263–265. doi: 10.1002/hep.20296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoneda M, Hotta K, Nozaki Y, Endo H, Uchiyama T, Mawatari H, Iida H, Kato S, Fujita K, Takahashi H, Kirikoshi H, Kobayashi N, Inamori M, Abe Y, Kubota K, Saito S, Maeyama S, Wada K, Nakajima A. Liver Int. 2009;29:1078–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calvaruso V, Craxi A. J. Viral Hepat. 2009;16:529–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo L, Richardson KS, Tucker LM, Doll MA, Hein DW, Arteel GE. Hepatology. 2004;40:583–589. doi: 10.1002/hep.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magness ST, Bataller R, Yang L, Brenner DA. Hepatology. 2004;40:1151–1159. doi: 10.1002/hep.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner DA, Westwick J, Breindl M. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:G589–G595. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.4.G589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myllyharju J. Ann. Med. 2008;40:402–417. doi: 10.1080/07853890801986594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ju H, Zhao S, Jassal DS, Dixon IM. Cardiovasc. Res. 1997;35:223–232. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arthur MJ. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G245–G249. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.2.G245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ushio-Fukai M. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;71:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devy L, Blacher S, Grignet-Debrus C, Bajou K, Masson V, Gerard RD, Gils A, Carmeliet G, Carmeliet P, Declerck PJ, Noel A, Foidart JM. FASEB J. 2002;16:147–154. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0552com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorrentino P, Terracciano L, D'Angelo S, Ferbo U, Bracigliano A, Vecchione R. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010;105:336–344. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]