Abstract

Objectives

Because of difficulties associated with pediatric speech testing, most pediatric cochlear implant (CI) speech studies necessarily involve basic and simple perceptual tasks. There are relatively few studies regarding Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users' perception of more difficult speech materials (e.g., words and sentences produced by multiple talkers). Difficult speech materials and tests necessarily require older pediatric CI users, who may have different etiologies of hearing loss, duration of deafness, CI experience. The present study investigated how pediatric CI patient demographics influence speech recognition performance with relatively difficult test materials and methods.

Method

In this study, open-set recognition of multi-talker (two males and two females) Mandarin Chinese disyllables and sentences were measured in 37 Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users. Subjects were grouped according to etiology of deafness and previous acoustic hearing experience. Group 1 subjects were all congenitally deafened with little-to-no acoustic hearing experience. Group 2 subjects were not congenitally deafened and had substantial acoustic hearing experience prior to implantation. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed within each group using subject demographics such as age at implantation and age at testing.

Results

Pediatric CI performance was generally quite good. For Group 1, mean performance was 82.3% correct for disyllables and 82.8% correct for sentences. For Group 2, mean performance was 76.6% correct for disyllables and 84.4% correct for sentences. For Group 1, multiple linear regression analyses showed that age at implantation predicted disyllable recognition, and that age at implantation and age at testing predicted sentence recognition. For Group 2, neither age at implantation nor age at testing predicted disyllable or sentence recognition. Performance was significantly better with the female than with the male talkers.

Conclusions

Consistent with previous studies' findings, early implantation provided a significant advantage for profoundly deaf children. Performance for both groups was generally quite good for the relatively difficult materials and tasks, suggesting that open-set word and sentence recognition may be useful in evaluating speech performance with older pediatric CI users. Differences in disyllable recognition between Groups 1 and 2 may reflect differences in adaptation to electric stimulation. The Group 1 subjects developed speech patterns exclusively via electric stimulation, while the Group 2 subjects adapted to electric stimulation relative to previous acoustic patterns.

Keywords: cochlear implant, children, speech, Mandarin Chinese, pediatric

1. Introduction

Cochlear implants (CIs) can restore hearing sensation to patients with profound sensorineural hearing loss. Many post-lingually deafened adult CI users are capable of high levels of speech understanding. CIs allow deaf children to acquire similarly high levels of speech understanding [1]. Similar to adult CI populations, there is a wide variability in pediatric patient outcomes [2]. While many studies have explored pediatric CI patient performance [2–5], most of these studies have focused on English speech perception by English-speaking pediatric CI users. Previous studies with French [6,7], Belgian [8], and Dutch [9–11] pediatric patients showed that cochlear implantation greatly benefited the speech development of these profoundly deaf children.

The majority of native Mandarin-speaking CI users were implanted as children. Most Chinese pediatric CI users are pre-lingually deafened, i.e., they did not acquire speech before deafness, typically because of congenital hearing loss. There is a sensitive period for development of the human central auditory pathways, beyond which there is limited plasticity [12]. Therefore, implantation at an early age is crucial for pre-lingually deafened CI users' speech development. Other pediatric CI users may have acquired speech through acoustic hearing (aided or unaided) before deafness. For these (typically) late-implanted pediatric patients, CI outcomes may depend on the duration and quality of acoustic hearing during auditory development. Extended auditory deprivation due to hearing loss may limit the benefit of cochlear implantation. Alternatively, post-lingually deafened pediatric CI users may greatly benefit from implantation if there was sufficient exposure to acoustic hearing. In general, little is known about differences in speech performance between pre- and post-lingually deafened Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users.

English, French, German and Dutch are non-tonal, Indo-European languages. In contrast, Chinese (which is spoken by the greatest number of people in the world) is a tonal, Sino-Tibetan language. Mandarin Chinese syllables are produced with one of four lexical tones: Tone 1 (high-flat), Tone 2 (rising), Tone 3 (falling-rising), and Tone 4 (falling). The same syllable produced with different tones can have vastly different meanings [13,14]. Fundamental frequency (F0) cues contribute strongly to Chinese tone recognition, which in turn contributes strongly to Chinese sentence recognition. Because CI devices typically provide only 12 – 22 spectral channels (too few to support good frequency resolution), Chinese tone recognition is difficult and CI users must rely more strongly on amplitude and duration cues [15].

Most CI speech perception studies (with adults or children) research have been conducted with English-speaking subjects. There are comparatively few CI studies with Chinese CI users. Several Taiwanese studies have investigated Mandarin Chinese-speaking CI users' speech perception. Huang et al. [13] evaluated speech performance and auditory function in four adult, Mandarin-speaking, post-lingually deafened users of Cochlear's Nucleus-22 device; they found significant and continuous improvement in all subjects' speech perception and auditory capabilities after implantation. Wu and colleagues [14] reported a negative correlation between Chinese vowel, word, sentence recognition and age at implantation for Chinese pediatric CI users. Peng et al. [16] found that pre-lingually deafened pediatric CI users exhibited poor Mandarin Chinese tone recognition and tone production. Wang et al. [17] found long-term benefit for cochlear implantation in a longitudinal study with Taiwanese pediatric CI users. Recent studies have focused on the contribution of Chinese tone recognition to CI users' understanding of Mandarin Chinese [18–20].

To date, most Chinese pediatric CI studies have evaluated speech understanding in terms of language awareness [21], lexical tone production and perception [22,23], Cantonese word recognition [24], as well as closed-set Mandarin early speech perception [25]. Because of general difficulties associated with testing children (e.g., limited language development, subject attention, etc.), very few studies have evaluated Chinese CI users' open-set word or sentence recognition with multiple talkers. Understanding words and sentences is essential to daily life, and may better reflect the ultimate benefit of implantation for pediatric patients. Some Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users may be old enough to understand more difficult or complex speech materials (e.g., words and sentences produced by multiple talkers). Older pediatric CI users may also have different etiologies of hearing loss. Some may be congenitally deafened and implanted at an early age, while others may have experienced significant amounts of acoustic hearing (aided or unaided) before implantation. As such, speech pattern development may be different across pediatric CI users. Pre-lingually deafened CI users develop speech patterns exclusively via electric hearing. Other CI users may adapt novel electric stimulation patterns to previous acoustic patterns; depending on age at onset of hearing loss and/or the severity of hearing loss, these acoustic patterns may (or may not) be sufficient for adaptation. Different types of speech tests may elicit differences between pediatric CI users. Word recognition may be more sensitive to the peripheral representation, while sentence recognition may depend greatly on contextual cues.

In this study, speech recognition was measured in Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users to see how patient demographics influence performance with relatively difficult test materials and methods. Subjects were grouped according to etiology of deafness and previous acoustic hearing experience. Group 1 subjects were all congenitally deafened with little-to-no acoustic hearing experience. Group 2 subjects were not congenitally deafened and had substantial acoustic hearing experience prior to implantation. Open-set multi-talker (2 male and 2 female talkers) disyllabic word and sentence recognition was measured in each subject. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to see whether patient demographics (e.g., age at implantation, age at testing) predicted speech performance.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Thirty-seven pediatric CI users participated in this study. All subjects were implanted at the Shanghai Eye, Ear, Nose & Throat (EENT) hospital; this study was conducted in the Vision and Audition Center of the Shanghai EENT hospital. Subject inclusion criteria consisted of bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss, no evidence of mental retardation, at least 6 years old and Mandarin Chinese as the native language. The profound hearing loss was confirmed using auditory brainstem response (ABR). The morphologies of middle and inner ear were evaluated with high resolution computer tomography (HRCT) and all showed no pathological CT findings.

Table 1 shows demographic details for all subjects. There were 21 male and 16 female subjects. Across all subjects, the mean age at testing was 8.6 years (range: 6.0–17.9 years), the mean age at implantation was 4.2 years (range: 1.2–17.5 years), and the mean amount of CI experience was 4.4 years (range: 0.3–11.1 years). All but two subjects were implanted with Cochlear's Nucleus-24 device (ACE strategy); two subjects were implanted with Advanced Bionics' HiRes 90K device (Fidelity 120 strategy). All subjects were unilateral CI users. Five subjects were implanted in the left ear, and thirty-two subjects were implanted in the right ear.

Table 1.

CI subject demographics. Abbreviations: F = Female, M = Male, AAT = Age at testing (year), AAI = Age at implantation (year), CI exp = Amount of cochlear implant experience (years), Nuc-24 = Nucleus-24, ACE = Advance combination encoder, F120 = Fidelity 120.

| Group 1 | Gender | AAT | AAI | CI exp | Etiology | Device | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 6.00 | 3.50 | 2.50 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 2 | M | 6.25 | 4.75 | 1.50 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 3 | F | 6.25 | 3.75 | 2.50 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 4 | M | 6.33 | 1.58 | 4.75 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 5 | M | 6.33 | 1.50 | 4.83 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 6 | M | 6.33 | 1.08 | 5.25 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 7 | M | 6.42 | 2.42 | 4.00 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 8 | M | 6.58 | 1.50 | 5.08 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 9 | F | 6.58 | 1.50 | 5.08 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 10 | M | 6.67 | 4.33 | 2.33 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 11 | F | 6.67 | 1.50 | 5.17 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 12 | F | 6.67 | 1.33 | 5.33 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 13 | F | 7.50 | 5.50 | 2.00 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 14 | F | 7.50 | 1.17 | 6.33 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 15 | F | 7.58 | 1.58 | 6.00 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 16 | M | 7.67 | 1.58 | 6.08 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 17 | F | 7.75 | 1.50 | 6.25 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 18 | M | 7.92 | 2.00 | 5.92 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 19 | M | 8.17 | 2.08 | 6.08 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 20 | M | 8.42 | 2.17 | 6.25 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 21 | F | 8.50 | 2.25 | 6.25 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 22 | M | 8.75 | 1.75 | 7.00 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 23 | F | 9.08 | 5.17 | 3.92 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 24 | F | 10.50 | 2.42 | 8.08 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 25 | F | 11.75 | 2.58 | 9.17 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 26 | M | 13.50 | 2.42 | 11.08 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 27 | F | 14.50 | 7.67 | 6.83 | congenital | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 27 subjects | 14F, 13M | ||||||

| Mean | 8.01 | 2.61 | 5.39 |

| Group 2 | Gender | AAT | AAI | CI exp | Etiology | Device | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | M | 6.42 | 5.50 | 0.92 | LVAS | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 29 | M | 6.83 | 5.33 | 1.50 | unknown | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 30 | M | 7.08 | 4.58 | 2.50 | LVAS | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 31 | M | 7.83 | 6.83 | 1.00 | LVAS | HiRes 90K | F120 |

| 32 | M | 8.25 | 6.17 | 2.08 | unknown | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 33 | F | 8.42 | 4.50 | 3.92 | LVAS | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 34 | M | 11.75 | 8.00 | 3.75 | LVAS | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 35 | M | 13.25 | 12.08 | 1.17 | unknown | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 36 | M | 13.33 | 13.08 | 0.25 | unknown | Nuc-24 | ACE |

| 37 | F | 17.92 | 17.50 | 0.42 | unknown | HiRes 90K | F120 |

| 10 subjects | 2F, 8M | ||||||

| Mean | 10.11 | 8.36 | 1.75 |

| All | Gender | AAT | AAI | CI exp | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 subjects | 16F, 21M | ||||||

| Mean | 8.57 | 4.17 | 4.41 |

Subjects were divided into two groups according to the etiology of deafness and the amount of previous acoustic hearing experience. Group 1 consisted of 27 subjects. All subjects in Group 1 were congenitally deafened and diagnosed with severe or profound sensorineural hearing loss, as confirmed by objective auditory testing (ABR). Ten subjects in Group 1 were given high-power hearing aids (HAs) for several months before implantation to see whether there was potential low-frequency acoustic hearing (there was not). The remaining 17 subjects in Group 1 were implanted soon after diagnosis of severe sensorineural hearing loss and did not use HAs prior to implantation. Given the congenital deafness and the very limited exposure to acoustic hearing, Group 1 subjects would be generally considered to be pre-lingually deafened. For Group 1, the mean age at testing was 8.0 years (range: 6.0–14.5 years), the mean age at implantation was 2.6 years (range: 1.1–7.7 years), and the mean amount of CI experience (age at testing – age at implantation) was 5.4 years (range: 1.5–11.1 years).

Group 2 consisted of 10 subjects. Etiology of deafness varied across Group 2 subjects; none were congenitally deafened. Nine of the 10 subjects used HAs before receiving their CIs; the mean HA use was 5.2 years (range: 2.0–8.5 years). The remaining subject was implanted immediately after diagnosis of profound hearing and did not use HAs prior to implantation. For Group 2, the mean age of testing was 10.1 years (range: 6.4–17.9 years), the mean age of implantation was 8.4 years (range: 4.5–17.5 years), and the mean amount of CI experience was 1.8 years (range: 0.3–3.9 years).

2.2 Stimuli

The Zhanghua Mandarin Speech Test Materials (MSTMs) were used for testing [26]. The Zhanghua MSTMs consists of 4 batteries of test materials and 1 battery of practice materials. Each test battery consists of 1 dissyllabic test list (50 disyllables) and 1 sentence test list (10 sentences, 50 keywords per list). Disyllables consisted of both nouns and verbs; an example list is shown in Appendix 1. Sentences consisted of 2 to 11 words (2 to 8 keywords), and example list is shown in Appendix 2. Each sentence list contained both questions and statements. The speech materials used in the dissyllabic and sentence test lists were generally easy and familiar in daily life. The dissyllabic test lists were phonemically balanced in three dimensions: vowels, consonants and Chinese tones. Disyllable and sentence test lists were normed for equal difficulty with native Chinese Mandarin-speaking normal-hearing (NH) listeners [26,27]. Therefore, while the contents of the four batteries of test materials may have been different, the test batteries met the basic requirements for developing speech testing materials: familiarity, homogeneity, phonemic balance and equivalence [28]. The practice battery contained 1 disyllabic practice list (10 disyllables) and 1 sentence practice list (5 sentences).

All speech materials were digitally recorded at East Radio Shanghai, and produced by four experienced Mandarin broadcasters (two males and two females). Each talker produced the battery of practice materials and but only one battery of test materials (randomly selected). Recordings were made in a sound-treated booth using a high-quality microphone (Electro-voice RE20) connected a mixing desk (Soundcraft MBI Series 5). Speech stimuli were digitized (16-bit sampling at 44.1 kHz) and stored on compact disk. The mean F0 (across disyllables and sentences) was 181 Hz for Male 1, 156 Hz for Male 2, 259 Hz for Female 1 and 213 Hz for Female 2.

2.3 Procedures

Subjects were seated midway between two loudspeakers in a sound-treated room. The distance between the two loudspeakers was 1.5 m and the loudspeaker height was adjusted to be at the subject's ear level. Stimuli were presented at 65 dBA (comfortably loud) via compact disc player connected to an audiometer (GSI 61), connected to the loudspeakers. Before formal testing, subjects were given the practice battery to familiarize them with the test procedure. Each subject was tested using all four test batteries; the batteries were presented in a pseudo-random order with the constraint that two talkers of the same gender were not tested sequentially. Performance was scored according to the percent of disyllables or keywords correctly identified in each test. Performance was averaged across the two male and two female talkers to determine the percent correct for each talker gender.

For most subjects, a parent or guardian was present during testing to reduce subject anxiety. During testing, a dissyllabic (or sentence) test list was randomly selected from the stimulus set and presented to the subject, who was instructed to repeat what was heard. The entire test session was administered by the same experimenter. The experimenter judged the CI subject's response via high-quality headphones connected to the audiometer; the examiner was also able to see the subject through the booth window and therefore could also lip-read the subject's response. Performance was scored in terms of percent correct disyllables or keywords in sentences. For each subject, the total amount of time for testing was 40–60 minutes. All test materials were presented one time (without repeat) and no feedback was provided regarding the correctness of the response. Subjects were allowed to take breaks any time they felt fatigued.

3. Results

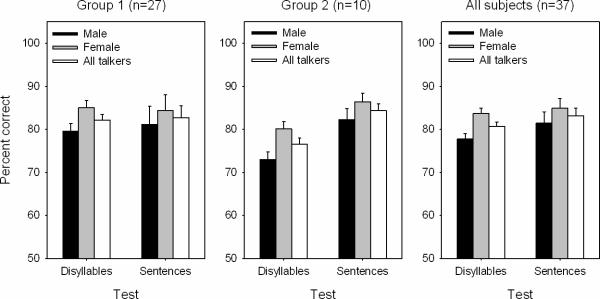

Figure 1 shows mean disyllable and sentence recognition performance with different talkers for Group 1 (left), Group 2 (middle) and all subjects (right). For Group 1, mean performance was 82.3% correct for disyllables and 82.8% correct for sentences. A two-way repeated measures analyses of variance (RM ANOVA), with talker (Female 1, Female 2, Male 1, and Male 2) and test (disyllable or sentence recognition) as factors, showed a significant effect for talker [F(3,78)=11.94, p<0.001], but not for test [F(1,78)=0.03, p=0.855]; however, there was a significant interaction between talker gender and test [F(3,78)=3.64, p=0.016]. Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that Group 1 disyllable recognition was significantly better with Female 1 than with Male 1 or Male 2 (adjusted p<0.001), and better with Female 2 than with Male 2 (adjusted p=0.024); there were no significant differences between the remaining talkers. Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that Group 1 sentence recognition was not significantly affected by talker.

Figure 1.

Mean disyllable and sentence recognition performance with different talkers for Group 1 (left), Group 2 (middle) and all subjects (right). The error bars show one standard error of the mean.

For Group 2, mean performance was 76.6% correct for disyllables and 84.4% correct for sentences. A two-way RM ANOVA, with talker and test as factors, showed significant effects for talker [F(3,27)=7.83, p<0.001] and test [F(1,27)=18.25, p=0.002]; there were no significant interactions [F(3,27)=1.38, p=0.271]. Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that Group 2 disyllable recognition was significantly better with Female 1 than with Male 1 (adjusted p=0.033) or Male 2 (adjusted p<0.001); there were no significant differences between the remaining talkers. Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that Group 2 sentence recognition was not significantly affected by talker.

Across all subjects, a two-way RM ANOVA, with talker and test as factors, showed a significant effect for talker gender [F(1,36)=50.01, p<0.001], but not for test material [F(1,36)=1.39, p=0.246]; there was a significant interaction [F(1,36)=6.81, p=0.013]. Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that both disyllable and sentence recognition was significantly better with female than with male talkers (adjusted p<0.001).

To see what demographic factors may have contributed to performance, single and multiple linear regression analyses were performed on disyllable and sentence recognition data; the results are shown in Table 2. Across all subjects, single linear regression analyses showed a weak but significant correlation between age at implantation and disyllable recognition (r2=0.17, p=0.015); there was no correlation between age at implantation and sentence recognition. For Group 1, single linear regression analyses showed that both disyllable (r2=0.58, p p<0.001) and sentence recognition (r2=0.60, p<0.001) were strongly and significantly correlated with age at implantation. For Group 2, single linear regression analyses showed that neither disyllable recognition nor sentence recognition was significantly correlated with age at implantation.

Table 2.

Results of single (top) and multiple linear regression analyses (bottom) performed on disyllable and sentence recognition data. Significant p-values are shown in bold and italic. Abbreviations: AAT = Age at testing, AAI = Age at implantation, dF = degrees of freedom, res = residual.

| Subject | Test | Single linear regression fit | r2 | AAT | AAI | dF,res | F-ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Disyllable | 84.5 − (0.91*AAI) | 0.17 | 0.015 | 1,35 | 6.554 | 0.015 | |

| Sentence | 87.0 − (0.92*AAI) | 0.04 | 0.258 | 1,35 | 1.324 | 0.258 | ||

| Group 1 | Disyllable | 93.2 − (4.20*AAI) | 0.58 | <0.001 | 1,25 | 34.553 | <0.001 | |

| Sentence | 108.2 − (9.73*AAI) | 0.60 | <0.001 | 1,25 | 36.730 | <0.001 | ||

| Group 2 | Disyllable | 72.5 + (0.49*AAI) | 0.17 | 0.238 | 1,25 | 1.618 | 0.238 | |

| Sentence | 77.3 + (0.84*AAI) | 0.30 | 0.105 | 1,25 | 3.348 | 0.105 |

| Subject | Test | Multiple linear regression fit | r2 | AAT | AAI | dF,res | F-ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Disyllable | 81.6 + (0.47*AAT) − (1.17*AAI) | 0.17 | 0.487 | 0.030 | 2,34 | 3.477 | 0.042 |

| Sentence | 70.8 + (2.59*AAT) − (2.36*AAI) | 0.12 | 0.082 | 0.042 | 2,34 | 2.306 | 1.115 | |

| Group 1 | Disyllable | 94.8 − (0.24*AAT) − (4.07*AAI) | 0.58 | 0.686 | <0.001 | 2,24 | 16.775 | <0.001 |

| Sentence | 87.4 + (3.15*AAT) − (11.42*AAI) | 0.69 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 2,24 | 27.192 | <0.001 | |

| Group 2 | Disyllable | 67.3 + (1.65*AAT) − (0.88*AAI) | 0.28 | 0.333 | 0.54 | 2,7 | 1.357 | 0.318 |

| Sentence | 82.9 − (1.77*AAT) + (2.31*AAI) | 0.37 | 0.395 | 0.212 | 2,7 | 2.048 | 0.199 |

Across all subjects, multiple linear regression analyses showed a weak but significant correlation between age at implantation and disyllable recognition (r2=0.17, p=0.042); there was no correlation between age at implantation and sentence recognition. For both disyllables and sentences, age at implantation was significantly weighted while age at testing was not. For Group 1, age at implantation strongly predicted disyllable recognition (r2=0.58, p p<0.001), while age at testing and age at implantation strongly predicted sentence recognition (r2=0.69; p=0.01 for age at testing and p<0.001 for age at implantation). For Group 2, neither age at testing nor age at implantation predicted disyllable or sentence recognition.

4. Discussion

In general, the present Mandarin-speaking, pediatric CI subjects scored well on the relatively difficult open-set, multi-talker disyllable and sentence recognition tasks. Age at implantation best predicted performance, especially for Group 1, while both age at implantation and age at testing predicted Group 1 sentence recognition performance. Performance was generally better with the female rather than the male talkers. Below we discuss the results in greater detail.

All of the present subjects were aged six years or older, beyond the critical period of central auditory processing development (3.5 years [12]). This allowed for testing with relatively difficult speech measures (open-set disyllable and sentence recognition), rather than somewhat easy tests used in previous pediatric Chinese CI studies. For clinical evaluation of English-speaking CI users, there are a number of standard and/or commonly-used speech materials, e.g. PB (phonetically balanced)-50 word lists, Northwestern University Tests Number 6 (NU-6) [29], Hearing in Noise Test (HINT) sentences [30], etc. For children, there are the PBK-50 word lists and the WIPI (Word Intelligibility by Picture Identification Test) [29]. Adult materials such as HINT sentences have been modified to be age-appropriate for pediatric listeners (HINT-C) [31]. Note that none of these materials was developed to measure CI patient performance. Currently, there are no standardized speech materials to test CI users' Mandarin speech recognition in China. The fact that the majority of implant recipients in China are children further complicates matters, as age-appropriate test materials have not been developed for pediatric Chinese CI users.

In the present study, the Zhanghua MSTMs were used. The test materials were all familiar and widely used in daily life. The words used in the disyllable tests were phonemically balanced across lists; the words used in the sentences were phonetically balanced across lists. Performance-intensity functions were used to analyze the validity of the test materials [32,33]. The validity of the dissyllable test lists was further evaluated in subjects with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss [34]. Therefore, the test materials fulfilled the basic criteria for speech recognition testing. However, the Zhanghua MSTMs were evaluated using only adult NH listeners; the materials were never evaluated with adult or pediatric CI users. Nonetheless, the present results suggest that the Zhanghua MSTMs were not overly difficult. Mean recognition (across all subjects and talkers) was 80.1% correct for disyllables (range = 58%–92% correct) and 83.2% correct for sentences (range = 33.5%–100% correct), well within the range of performance observed for adult CI users. For example, mean single-syllable vowel and tone recognition for Mandarin-speaking adult and adolescent CI users was 90% and 63% correct, respectively [35]. For sentence recognition, the mean recognition of Mandarin Hearing in Noise Test (M-HINT) sentences for adult Mandarin CI users was 69.21% correct (range: 14.8–99.1% correct; from unpublished pilot data collected at Communication and Auditory Neuroscience, House Ear Institute), comparable to the present sentence recognition scores. The slightly better performance observed with MSTMs sentences was probably due to the fact that there are more words in each sentence for M-HINT sentences (10 words each sentence) and the speaking rate for M-HINT sentences is also relatively fast (4.5 words per second). Note that in this study, the age at testing was significantly contributed to Group 1 sentence recognition performance, suggesting that some adjustment to the sentence materials may be needed. Still, performance in the present study was quite comparable to performance with adult CI users, suggesting that while the Zhanghua MSTMs may need to be adjusted to be age-appropriate, the present pediatric CI users did not have great difficulty with the materials. Compared to the relatively easy speech measures typically used to evaluate pediatric performance in Mandarin CI users, the greater difficulty associated with the Zhanghua MSTMs allowed for greater sensitivity to subject demographics (e.g., etiology of deafness, age at implantation, age at testing, etc.).

The present speech performance was comparable to that of previous studies with Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users. For example, Han et al. [23] measured closed-set lexical tone perception in 20 pediatric Mandarin CI users (age at testing: 3.5–16.5 years; age at implantation: 1.3–13.5 years). Mean tone recognition scores at baseline (HiRes strategy), one, three, and six months (HiRes 120 strategy) were 74%, 75%, 75% and 82% correct, respectively; six of the twenty subjects scored >90% correct. Wu et al. [36] measured open-set Mandarin word recognition using the Mandarin Lexical Neighborhood Test (M-LNT) in 28 congenitally deafened children (age at implantation: 1.1–8.2 years; age at testing: 6.0–12.6 years ). For CI subjects implanted younger than 3 years old, mean word recognition was 80.0% and 70.5 % correct for the easy and hard versions of the M-LNT, respectively. For CI subjects implanted older than 3 years old, mean word recognition was 62.5% and 59.1% correct for the easy and hard versions of the M-LNT, respectively.

The present results are also comparable to those with English-speaking pediatric CI users. Frisch and Pisoni [1] measured open-set English word recognition performance in prelingually deafened, pediatric CI users (age at implantation: 2.6–8.9 years; age at testing: 4.5–10.8 years) using the Lexical Neighborhood Test (LNT). Mean word recognition scores were 52% and 39% correct for the easy and hard word lists, respectively, much lower than M-LNT performance in Wu et al. [36] or the disyllable recognition performance in the present study. Chin et al. [37] measured minimal pairs perception (MP1 test) in pediatric CI users (age at implantation: 1.4–5.3 years; age at testing: 4.8–7.8 years); mean performance was 88.1% correct. Peng et al. [38] measured intonation recognition in 26 pre-lingually deafened CI users (age at implantation: 1.5–6.3 years; age at testing: 7.48–20.7 years); mean performance was 70.1% correct. Thus the present results seem comparable to those with similar speech measures, similarly-aged subjects, and are even comparable to those with different listening tasks and/or language.

Many studies have compared performance between pre- and post-lingually deafened CI users [39–42]. For adults, speech performance is generally worse for pre-lingually deafened than post-lingually deafened CI users [43]. In this study with pediatric subjects, disyllable recognition was better for Group 1 than for Group 2. Given the demographics, Group 1 would be characterized as pre-lingually deafened, while Group 2 might be characterized as post-lingually deafened (although the completeness of language acquisition and onset of hearing loss are difficult to ascertain). The Group 1 subjects were implanted much earlier (mean – 2.61 years) than the Group 2 subjects (mean – 8.36 years). The speech pattern development via electric hearing for Group 1 may have been stronger than that with acoustic hearing for Group 2. Because of the later implantation, the Group 2 subjects necessarily had less CI experience. It is possible that greater experience might improve disyllable recognition. If the patterns learned during acoustic hearing did not contain sufficient high-frequency speech cues, restoring these cues via CI may eventually provide better performance. Alternatively, the Group 2 subjects needed to adapt to the electric patterns relative to the previous acoustic patterns. Again, more CI experience might allow for greater adaptation for Group 2. Sentence recognition was similar between Groups 1 and 2. Group 2 subjects may have effectively used contextual cues available in the sentences to compensate for the possibly poorer word recognition.

For Group 1, the age at implantation most strongly predicted speech performance. The effect of age at implantation on CI performance has been well documented Kileny et al. [5] found that speech understanding worsened with increasing age at implantation, and co-varied with the amount of CI experience. Snik et al. [9] similarly found that open-set speech recognition by pre-lingual CI users worsened with increasing age at implantation. Harrison et al. [44] reported that children implanted at an early age out-performed those implanted at a later age, even after long-term CI experience. Age at implantation has been previously correlated with pediatric CI users' speech understanding for many languages, including English [45], Belgian [8], and French [6]. Age at implantation has also been studied in pediatric Chinese-speaking CI users. Chinese speech production has been significantly correlated with age at implantation [16]. Cantonese [24] and Mandarin speech perception [14,16,23,36] has been significantly correlated with pediatric CI users' age at implantation. Sarant et al. [2] suggested that auditory deprivation could limit the development of auditory neural processing structures, or even degenerate these structures. There is an early, critical period for language development and acquisition [12], beyond which it becomes difficult to develop normal speech perception capabilities. The early deprivation of auditory stimulation and delay in tone acquisition limit Chinese tone perception by pre-lingual Mandarin-speaking children [46]. On average, Group 1 subjects were implanted at 2.6 years old, the youngest at 1.1 years old, well within the critical period for auditory development. In contrast, the mean age at implantation for Group 2 subjects was 8.4 years old, with the youngest implanted at 4.5 years old, well beyond this critical period. However, Group 2 subjects had some experience with acoustic hearing, mostly via HAs. This may have offset the later age at implantation, and may partly explain why age at testing and age at implantation did not affect speech performance.

The present data showed that pediatric CI subjects were sensitive to talker gender. While the difference in performance was small (5 percentage points, on average), mean recognition was significantly better with the female than with the male talkers. Note that there was a potential confound for the talker gender analyses, in that all talkers did not produce all the speech materials. Female 1 produced only disyllable and sentence lists 1; Male 1 produced only disyllable and sentence lists 2; Female 2 produced only disyllable and sentence lists 3; Male 2 produced only disyllable and sentence lists 4. It is possible that the observed talker gender effects reflect list difficulty. However, because the lists were balanced in terms of familiarity, homogeneity and phonemic/phonetic content, it seems unlikely that subjects performed better with particular lists rather than talkers. Also, performance with the female talkers was significantly better for both disyllable and sentence recognition, increasing the likelihood that CI subjects were sensitive to talker gender rather than test materials.

Previous studies have shown that different speaker characteristics (e.g., voice gender, talker F0) may significantly influence CI users' speech understanding [47]. While there may be optimal talkers due to patient-specific factors (e.g., location of implanted electrodes, frequency allocation, etc.), pediatric CI users' optimal pattern may be more strongly influenced by experience. In China, children (especially pre-schoolers) are nearly constantly accompanied by their mothers. Also, the strong majority of teachers in kindergartens and elementary schools are female. Thus, Chinese pediatric CI users have much greater exposure to female talkers, which may promote better speech understanding, even with unfamiliar female talkers.

5. Conclusions

The present study revealed several significant findings regarding Mandarin-speaking pediatric CI users' speech perception:

-

1)

In general, the present pediatric CI subjects (aged 6 and older) were capable of good open-set, multi-talker word and sentence recognition, suggesting that more difficult speech materials and tests may be appropriate for older pediatric CI users.

-

2)

Speech recognition was significantly better with the female talkers than with the male talkers.

-

3)

Age at implantation strongly predicted congenitally deafened (Group 1) CI subjects' disyllable and sentence recognition; age at testing also predicted Group 1 sentence recognition, suggesting a developmental component to these subjects' speech performance. For Group 2 (late implanted, with some previous acoustic experience), speech performance was not well-predicted by age at implantation or age at testing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the children who participated in this study. We are also grateful to Justin Aronoff for assistance with the statistical analyses. The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30872867) and NIH grant R01-DC004993.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1.

Example of disyllable test list.

| Number | Mandarin | Chinese Pinyin | English meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

shàng kè | class |

| 2 |

|

jí hé | put together |

| 3 |

|

dà mén | gate |

| 4 |

|

shè lì | found |

| 5 |

|

dān xīn | worry |

| 6 |

|

wàng jì | forget |

| 7 |

|

dào qiàn | sorry |

| 8 |

|

diàn chí | battery |

| 9 |

|

dì zhĭ | address |

| 10 |

|

ér tóng | child |

| 11 |

|

gē xīng | singer |

| 12 |

|

gŭ dài | old times |

| 13 |

|

cè shì | test |

| 14 |

|

hū xī | breath |

| 15 |

|

jià gé | price |

| 16 |

|

kāi chē | drive |

| 17 |

|

lè guān | positive |

| 18 |

|

pŭ shí | honest |

| 19 |

|

rè shŭi | hot water |

| 20 |

|

lǜ sè | green |

| 21 |

|

tú àn | pattern |

| 22 |

|

wēn nuăn | warm |

| 23 |

|

wŭ shù | kungfu |

| 24 |

|

xiāng dĕng | even |

| 25 |

|

yí dòng | move |

| 26 |

|

qū zhé | twisted |

| 27 |

|

zhēng duó | compete |

| 28 |

|

zhōu wéi | nearby |

| 29 |

|

zì diăn | dictionary |

| 30 |

|

băo hù | protect |

| 31 |

|

bàn fă | method |

| 32 |

|

gāng bĭ | pen |

| 33 |

|

biăo dá | express |

| 34 |

|

bào míng | apply |

| 35 |

|

hē jiŭ | drink |

| 36 |

|

măn yì | satisfaction |

| 37 |

|

rén mín | people |

| 38 |

|

nóng yào | bug spray |

| 39 |

|

jié yuē | saving |

| 40 |

|

fàng shŏu | release |

| 41 |

|

zhìdìng | draft |

| 42 |

|

huŏ zāi | blaze |

| 43 |

|

zhŏng lèi | sort |

| 44 |

|

zhuò zhĕ | author |

| 45 |

|

yăn yuán | actor |

| 46 |

|

chá yè | tea |

| 47 |

|

jīng shén | spirit |

| 48 |

|

tuìxiū | retire |

| 49 |

|

jiàng luò | land |

| 50 |

|

lĕng qì | air conditioner |

Appendix 2.

Example of sentence test list.

| Number | Mandarin Sentence | Number of keywords | Chinese Pinyin | English meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

2 | kuài qĭng jìn! | Please come in! |

| 2 |

|

2 | xiàn zài qĭ chuáng. | Get up now. |

| 3 |

|

3 | zhè shuāng xié tài xiăo le. | These shoes are too small. |

| 4 |

|

7 | tā qù yóu jú măi yóu piào. | He goes to the post office to buy stamps. |

| 5 |

|

7 | xīng qī tiān yì qĭ qù pá shān. | We will climb a mountain together on Sunday. |

| 6 |

|

6 | jiè de dōng xī wŏ yĭ jīng huá le. | I already returned all the things I borrowed. |

| 7 |

|

6 | qĭng liú xià nĭ de diàn huà hào mă. | Please leave your telephone number. |

| 8 |

|

5 | nĭ zĕn me zhī dào? | How do you know? |

| 9 |

|

4 | yŏu shén me shì er ma? | What do you need? |

| 10 |

|

8 | chē zhàn duì miàn shì shén me dì fāng? | What is the place across from the station? |

References

- [1].Frisch SA, Pisoni DB. Modeling spoken word recognition performance by pediatric cochlear implant users using feature identification. Ear Hear. 2000;21:578–589. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sarant JZ, Blamey PJ, Dowell RC, Clark GM, Gibson WP. Variation in speech perception scores among children with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2001;22:18–28. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Osberger MJ, Fisher L, Zimmerman-Phillips S, Geier L, Barker MJ. Speech recognition performance of older children with cochlear implants. Am J Otol. 1998;19:152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].O'Donoghue GM, Nikolopoulos TP, Archbold SM. Determinants of speech perception in children after cochlear implantation. Lancet. 2000;356:466–468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kileny PR, Zwolan TA, Ashbaugh C. The influence of age at implantation on performance with a cochlear implant in children. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:42–46. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Uziel AS, Sillon M, Vieu A, Artieres F, Piron JP, Daures JP, et al. Ten-year follow-up of a consecutive series of children with multichannel cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:615–628. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000281802.59444.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Uziel AS, Reuillard-Artieres F, Sillon M, Vieu A, Mondain M, Piron JP, et al. Speech-perception performance in prelingually deafened French children using the nucleus multichannel cochlear implant. Am J Otol. 1996;17:559–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Govaerts PJ, De Beukelaer C, Daemers K, De Ceulaer G, Yperman M, Somers T, et al. Outcome of cochlear implantation at different ages from 0 to 6 years. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:885–890. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Snik AF, Vermeulen AM, Brokx JP, van den Broek P. Long-term speech perception in children with cochlear implants compared with children with conventional hearing aids. Am J Otol. 1997;18:S129–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Snik AF, Vermeulen AM, Geelen CP, Brokx JP, van den Broek P. Speech perception performance of children with a cochlear implant compared to that of children with conventional hearing aids. II. Results of prelingually deaf children. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117:755–759. doi: 10.3109/00016489709113473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Snik AF, Vermeulen AM, Geelen CP, Brokx JP, van der Broek P. Speech perception performance of congenitally deaf patients with a cochlear implant: the effect of age at implantation. Am J Otol. 1997;18:S138–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sharma A, Dorman MF, Spahr AJ. A sensitive period for the development of the central auditory system in children with cochlear implants: implications for age of implantation. Ear Hear. 2002;23:532–539. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huang TS, Wang NM, Liu SY. Nucleus 22-channel cochlear mini-system implantations in Mandarin-speaking patients. Am J Otol. 1996;17:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wu JL, Yang HM. Speech perception of Mandarin Chinese speaking young children after cochlear implant use: effect of age at implantation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fu QJ, Zeng FG, Shannon RV, Soli SD. Importance of tonal envelope cues in Chinese speech recognition. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;104:505–510. doi: 10.1121/1.423251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Peng SC, Tomblin JB, Cheung H, Lin YS, Wang LS. Perception and production of mandarin tones in prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2004;25:251–264. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000130797.73809.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang NM, Huang TS, Wu CM, Kirk KI. Pediatric cochlear implantation in Taiwan: long-term communication outcomes. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Morton KD, Torrione PA, Jr., Throckmorton CS, Collins LM. Mandarin Chinese tone identification in cochlear implants: predictions from acoustic models. Hear Res. 2008;244:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lin YS, Peng SC. Effects of frequency allocation on lexical tone identification by Mandarin-speaking children with a cochlear implant. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:289–296. doi: 10.1080/00016480701596047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lin YS, Lu HP, Hung SC, Chang CP. Lexical tone identification and consonant recognition in acoustic simulations of cochlear implants. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:630–637. doi: 10.1080/00016480802032793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen X, Liu S, Liu B, Mo L, Kong Y, Liu H, et al. The effects of age at cochlear implantation and hearing aid trial on auditory performance of Chinese infants. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:263–270. doi: 10.3109/00016480903150528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Han D, Zhou N, Li Y, Chen X, Zhao X, Xu L. Tone production of Mandarin Chinese speaking children with cochlear implants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:875–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Han D, Liu B, Zhou N, Chen X, Kong Y, Liu H, et al. Lexical tone perception with HiResolution and HiResolution 120 sound-processing strategies in pediatric Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2009;30:169–177. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31819342cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lee KY, van Hasselt CA. Spoken word recognition in children with cochlear implants: a five-year study on speakers of a tonal language. Ear Hear. 2005;26:30S–37S. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200508001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zheng Y, Soli SD, Meng Z, Tao Y, Wang K, Xu K, et al. Assessment of Mandarin-speaking pediatric cochlear implant recipients with the Mandarin Early Speech Perception (MESP) test. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang H, Chen J, Wang S, Wang L, Guo LS, Zhao XY, et al. Edit and evaluation of Mandarin sentence materials for Chinese speech audiometry. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2005;40:774–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhang H, Wang S, Wang L, Chen J, Chen AT, Guo LS, et al. Development and equivalence evaluation of spondee lists of mandarin speech test materials. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;41:425–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tsai KS, Tseng LH, Wu CJ, Young ST. Development of a mandarin monosyllable recognition test. Ear Hear. 2009;30:90–99. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31818f28a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Penrod JP. Behavioral evaluation: peripheral hearing functions: speech threshold and recognition/discrimination testing. In: Katz J, editor. Handbook of Clinical Audiology. 4th edition Williams &Wilkins; Maryland: 1994. pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nilsson M, Soli SD, Sullivan JA. Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;95:1085–1099. doi: 10.1121/1.408469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nilsson MJ, Soli SD, Gelnett DJ. Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for children (HINT-C) Internal document, House Ear Institute. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang S, Zhang H, Wang L, Chen J, Ji C, Guo L, et al. Normative data of disyllabic Mandarin speech test materials for normally hearing people. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;21:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang H, Wang S, Chen J, Lin S, Wang L, Guo L. Performance-intensity function of mandarin monosyllable and sentence materials for normal-hearing subjects. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;22:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang S, Mannell R, Newall P, Zhang H, Han D. Development and evaluation of Mandarin disyllabic materials for speech audiometry in China. Int J Audiol. 2007;46:719–731. doi: 10.1080/14992020701558511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Luo X, Fu QJ, Wu HP, Hsu CJ. Concurrent-vowel and tone recognition by Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Hear Res. 2009;256:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wu JL, Lin CY, Yang HM, Lin YH. Effect of age at cochlear implantation on open-set word recognition in Mandarin speaking deaf children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chin SB, Finnegan KR, Chung BA. Relationships among types of speech intelligibility in pediatric users of cochlear implants. J Commun Disord. 2001;34:187–205. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(00)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Peng SC, Tomblin JB, Turner CW. Production and perception of speech intonation in pediatric cochlear implant recipients and individuals with normal hearing. Ear Hear. 2008;29:336–351. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318168d94d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Eisenberg LS. Use of the cochlear implant by the prelingually deaf. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1982;91:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gantz BJ, Tyler RS, Woodworth GG, Tye-Murray N, Fryauf-Bertschy H. Results of multichannel cochlear implants in congenital and acquired prelingual deafness in children: five-year follow-up. Am J Otol. 1994;15(Suppl 2):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Oh SH, Kim CS, Kang EJ, Lee DS, Lee HJ, Chang SO, et al. Speech perception after cochlear implantation over a 4-year time period. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:148–153. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000028111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Buckley KA, Tobey EA. Cross-modal plasticity and speech perception in pre- and postlingually deaf cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2011;32:2–15. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181e8534c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Santarelli R, De Filippi R, Genovese E, Arslan E. Cochlear implantation outcome in prelingually deafened young adults. A speech perception study. Audiol Neurootol. 2008;13:257–265. doi: 10.1159/000115435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Harrison RV, Gordon KA, Mount RJ. Is there a critical period for cochlear implantation in congenitally deaf children? Analyses of hearing and speech perception performance after implantation. Dev Psychobiol. 2005;46:252–261. doi: 10.1002/dev.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].O'Neill C, O'Donoghue GM, Archbold SM, Nikolopoulos TP, Sach T. Variations in gains in auditory performance from pediatric cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:44–48. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wei WI, Wong R, Hui Y, Au DK, Wong BY, Ho WK, et al. Chinese tonal language rehabilitation following cochlear implantation in children. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:218–221. doi: 10.1080/000164800750000955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Luo X, Fu QJ. Speaker normalization for chinese vowel recognition in cochlear implants. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52:1358–1361. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.847530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]