Abstract

It is well established that bone maintenance and healing is compromised in alcoholics. Adult mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in bone marrow (BMSCs) and adipose tissue (ASCs) likely contribute to bone homeostasis and formation. Direct and indirect alcohol exposure inhibits osteoprogenitor cell function through a variety of proposed mechanisms. The goal of this study was to characterize the effects of chronic alcohol ingestion on the native number and in vitro growth characteristics and multipotentiality of adult BMSCs and ASCs in a rat model. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats received a liquid diet containing 36% ethanol (EtOH) or an isocaloric substitution of dextramaltose (control). After 4, 8, or 12 weeks of the diet, ASCs were harvested from epididymal adipose tissue and BMSCs from femoral and tibial bone marrow. Cell doublings per day (CDs) and doubling times (DT) were determined for primary cells (P0) and cell passages 1 through 6 (P1-6). Fibroblastic, (CFU-F), adipogenic (CFU-Ad) and osteogenic (CFU-Ob) colony forming unit frequencies were assessed for P0, P3, and P6. The CDs and DTs were lower and higher, respectively, for ASCs and BMSCs harvested from EtOH versus control rats at all time points. The CFU-F, CFU-Ad and CFU-Ob were significantly higher in ASCs harvested from control versus EtOH rats for P0, P3, and P6 at all times. Both CFU-Ad and CFU-Ob were significantly higher in P0 BMSCs harvested from control versus EtOH rats after 12 weeks of the diet. The CFU-Ob for P3 BMSCs from control rats was significantly higher than those from ETOH rats after 8 and 12 weeks on the diet. All three CFU frequencies in ASCs from EtOH rats tended to decrease with increasing diet duration. The ASC cell and colony morphology was different between control and EtOH cohorts in culture. These results emphasize the significant detrimental effects of chronic alcohol ingestion on the in vitro expansion and multipotentiality of adult MSCs. Maintenance of the effects through multiple cell passages in vitro suggests cells may be permanently compromised.

Keywords: Adipose, bone marrow, adult stromal cells, alcohol, bone

Introduction

Alcoholism is accompanied by a plethora of pathologic conditions including impaired bone formation and homeostasis (Chakkalakal et al., 2002; Trevisiol et al., 2007a) characterized by signification suppression of both bone healing and turnover (Gong and Wezeman, 2004a). Reservoirs of adult stromal cells in adult tissues have the capacity for tissue regeneration (Park et al., 2007). Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) from bone marrow, bone marrow-derived stromal cells (BMSCs) are extensively characterized (Prockop, 1997). Adipose tissue is also an abundant source of stromal cells, adipose tissue-derived stromal cells (ASCs) (Gimble and Guilak, 2003). Both cell types have potential utility for tissue engineering approaches to bone maintenance and healing (Cowan et al., 2004; Cowan et al., 2005; Hicok et al., 2004; Justesen et al., 2004; Lopez et al., 2009; McIntosh et al., 2009). The effects of chronic alcohol consumption on bone health are likely multi-faceted, and the specific mechanisms of alcoholic bone disease have yet to be fully elucidated (Gonzalez-Reimers et al., 2005). Compromise of normal adult stromal cell function by chronic alcoholism is a likely mechanism of impaired bone formation characteristic of alcoholic bone.

Osteoprogenitor cells are vital for local tissue maintenance, and they are recruited to sites of injury (Lee et al., 2009; Tasso et al., 2009). Available information supports that alcohol mediated bone changes are initiated at the two major bone cell types, osteoblasts and osteoclasts, as well as their precursors (Chen et al., 2008; Rosa et al., 2008). Ethanol directly inhibits normal adult stromal cell function and multipotentiality in vitro, and systemic administration of ethanol inhibits osteoinduction by osteogenic progenitor cells in vivo (Cui et al., 2006; Dyer et al., 1998; Gong and Wezeman, 2004b; Rosa et al., 2008; Trevisiol et al., 2007b). Since ~70 million progenitor cells are required to produce a cubic centimeter of bone (Muschler and Midura, 2002), ethanol-induced reduction in adult stromal cell number expansion capacity and/or multipotentiality will significantly compromise bone structure and function.

There are distinct differences between BMSC and ASC isolation protocols, in vitro expansion, and multipotential efficiency (Sakaguchi et al., 2005; Yoshimura et al., 2007). Additionally, effects mediated by ethanol consumption may not be identical between the two cell types. The rat is an established model to investigate both the physiologic effects of alcohol consumption and adult stromal cell behavior and therapeutic applications. In order to develop mechanisms to reverse or prevent the effects of chronic alcoholism on adult stromal cell osteogenesis, it is critical to ascertain the specific temporal effects of chronic, high dose alcohol ingestion on adult stromal cell numbers, as well as expansion and multipotential. Further, knowledge of potential disparate alcohol effects on the two progenitor cell types and whether they resolve under ideal culture conditions is vital to therapies to restore normal stromal cell function. This study was designed to address these specific scientific questions and test the hypothesis that chronic, high dose alcohol ingestion reduces the number, and in vitro expansion rate and multipotentiality of adult BMSCs and ASCs.

Materials and Methods

General

Prior to study initiation, all procedures performed were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. A total of 30 male 12-week old Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were paired by body weight and assigned to two liquid diet cohorts, alcohol and control. Rats were allowed 7 days to become acclimated to the environment before beginning the research protocol. Feeding pairs then received Lieber-DeCarli liquid diets (DYETS Inc., Bethlehem, PA) containing either 36% ethanol (EtOH) or an isocaloric substitution of dextramaltose for ethanol (control). The Lieber-De Carli liquid diet without ethanol was administered 3 days before beginning the study to allow the animals to become accustomed to the diet. Animals fed alcohol were acclimated to the diet over a 1 week period by feeding ethanol at 12% ethanol derived calories (EDC) for three days, 24% EDC for three days and then 36% EDC for the remainder of the study. Rats were housed in individual shoe-box cages and fresh diet was provided daily between 7:00 and 9:00 AM. Animal housing was temperature and humidity controlled with a 12-hr light/dark cycle, and lights on from 6 AM to 6 PM. Food consumption was measured daily and rats were weighed weekly. The diets were prepared fresh daily. Within diet cohorts, animals received the diets for 4, 8, or 12 weeks (n=5/diet/time) at which time they were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation at 9:00 AM. Serum was collected immediately post-mortem via cardiac puncture and serum ethanol levels were determined with a commercially available kit (Synchron LX20 EtOH, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA) and Beckman Coutler DXC 600 Pro. Serum protein and total packed cell volume were also measured.

ASC Isolation

Immediately post-mortem, epididymal adipose tissue was aseptically harvested and then weighed. The ASCs were isolated according to published methods (Arrigoni et al., 2009; Gimble et al., 2007; Sgodda et al., 2007; Tholpady et al., 2003; Yoshimura et al., 2007). Briefly, epididymal adipose tissue was minced into small pieces with a #10 scalpel blade and then washed three times by suspending the tissue in an equal volume of PBS, vigorously agitating, and then allowing it to separate into 2 phases at room temperature. The infranatant containing hemopoietic cells was removed after each wash. Tissue was then digested in an equal volume of 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) in PBS at 37° C with gentle agitation (75 rpm) for 90 min. The suspension was vigorously agitated and then centrifuged at 1200 rpm (200 g) for 5 min to pellet the stromal vascular fraction (SVF). After digestion, the collagenase was neutralized by resuspending the pellet in an equal volume of 1% BSA and then centrifuging at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was then resuspended in stromal media consisting of DMEM-Ham’s F12 (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (MP Biomedical, Irvine, CA) and 20% characterized fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT). A small aliquot of the cell suspension was centrifuged and resuspended in an equal volume of red cell lysis buffer for 5 min. Total nucleated cell numbers per unit weight of adipose tissue was determined using trypan blue staining and hemocytometer assessment.

BMSC Isolation

Bone marrow was aseptically harvested from femora and tibiae of each rat immediately post mortem according to established methods (Lennon and Caplan, 2006). All soft tissue was removed from the bones and both bone ends were excised. Stromal medium (10 ml) from 5 ml heparinized syringes and 25-gauge needle was passed through the medullary cavity into a sterile centrifuge tube The marrow isolate was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min (200 g), and the pellet was resuspended in 5-ml of stromal medium. Total nucleated cell number was determined as described above.

ASC and BMSC In Vitro Growth Rates

Cell doublings (CD) and doubling times (DT) for P0-P6 of all animals were determined as previously reported (Vidal et al., 2006). Cells were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) on 96-well plates in duplicate in stromal medium. Seeding density was 2 × 104 nucleated cells/cm2 for ASCs and 5 × 104 cells/cm2 for BMSCs. The BMSCs from rats on the EtOH diet for 12 weeks required 20% fetal bovine serum in the stromal medium for detectable expansion, so 20% FBS was used for the BMSCs from control rats as well. The CD and DT were determined after 2, 4, and 6 days of culture for each passage according to the following formulae (Rainaldi et al., 1991; Vidal et al., 2006):

1) CD = ln(Nf/Ni)/ ln(2) 2) DT = CT/CD

CD = cell doublings, Nf = final cell number, Ni = initial cell number, DT = doubling time, CT = culture time. The DT data was log10 transformed prior to statistical analysis.

Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) Assays

Serial limit dilution assays to quantify fibroblast (CFU-F), adipogenic (CFU-Ad), and osteogenic (CFU-Ob) CFUs for P0, P3, and P6 were performed according to previous methods (Wu et al., 2000). Media changes were performed every 3 days. Positive CFU-F and CFU-Ad wells were defined as wells that contained at least 5 colonies and positive CFU-Ob wells contained at least 1 colony. Colonies measuring less than 600 µm in diameter and poorly stained colonies were not counted. Colony formation was assessed with bright field light microscopy at a magnification of 20× (Model DM5000, Leica Microcystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL).

The CFU frequency was determined using the following formula: F=e−x

F = fraction of negative wells, e = natural logarithm constant 2.71,×= number of CFUs per well. Based on a Poisson distribution of a clonal cell lineage, the value of F0 = 0.37 occurs when the number of total number of ASCs or BMSCs within a well contains a single CFU (Bellows and Aubin, 1989).

Fibroblastic Stromal cell Frequency (CFU-F)

For CFU-F assays, cells were maintained in stromal medium for a total of 14 days. Cultures were rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then fixed for 20 minutes in 1% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. The cells were stained in 0.1% toluidine blue in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour and subsequently gently rinsed 3 times with tap water.

Adipogenic Stromal Cell Frequency (CFU-A)

Cells were cultured in stromal medium for 7 days and then for 3 days in adipogenic induction medium consisting of DMEM-Ham’s F12, 10% FBS, 1% antibiotic/antimycotic, 33µmol/L biotin, 17µmol/L pantothenate, 1µmol/L insulin, 1µmol/L dexamethasone, 0.5 mmol/L isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), and 5µmol/L rosiglitazone (Avandia™, Glaxo Smith Kline). The cells were then cultured in the same medium minus IBMX and rosiglitazone for 10 days. Colonies were fixed for 20 min in 1% paraformaldehyde at room temperature and then stained with Oil Red O for 20 min followed by 3 distilled water rinses.

Osteogenic Stromal Cell Frequency (CFU-Ob)

For CFU-Ob assays, cells were first cultured for 7 days in stomal medium and then for 15 days in osteogenic induction medium consisting of DMEM-Ham’s F12, 10% FBS, 1% antibiotic/antimycotic, 10mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, 20 mmol/L dexamethasone, and 50 µg/mL sodium 2-phosphate ascorbate. Plates were fixed in 70% ethanol following 3 rinses with 150 mM NaCl. Colonies were stained with 2% Alizarin Red (pH 4.2) for 10 min at room temperature and then rinsed 5 times with distilled water.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (SAS 9.1.3, Cary, NC), and the Type I error was maintained at p = 0.05 for all comparisons. Outcome measures were assessed with MANOVA models and Tukey’s studentized range test for pairwise multiple comparisons of the means. Diet, week, cell type, passage, and day interactions were evaluated. Due to lack of significant effects of day and passage for DT and CD, data were collapsed over these two factors. The DT and CFU data was log10 transformed prior to analysis. Serum protein, packed cell volume, and adipose tissue weight were evaluated with ANOVA models. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

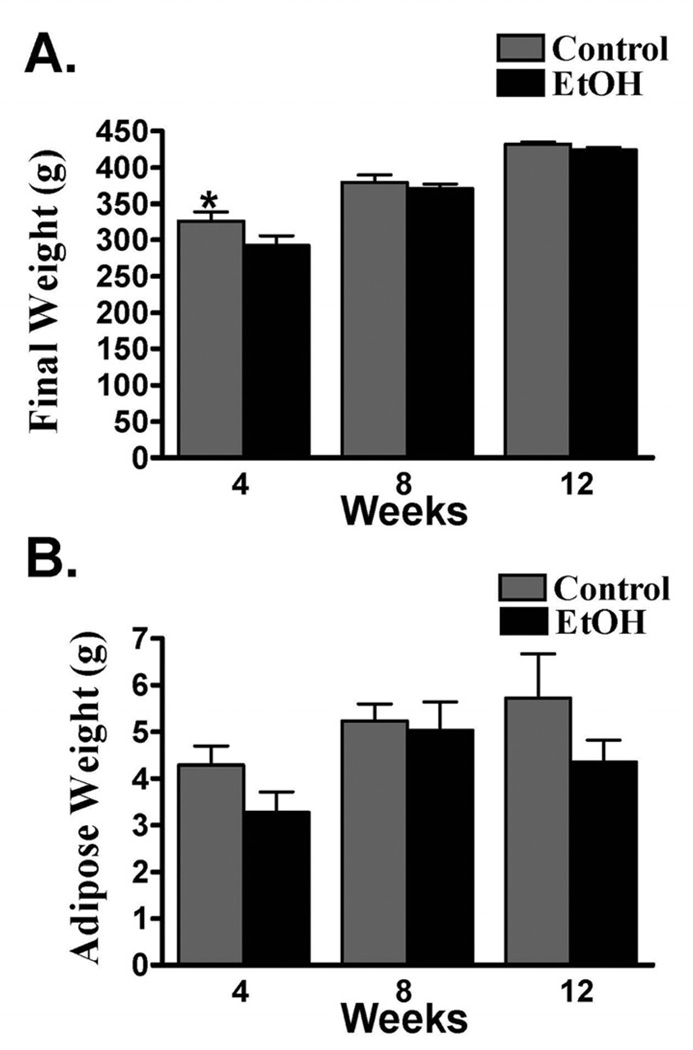

All rats were bright, alert and responsive during the study, and there was no gross post-mortem evidence of hepatic failure. Control rats (326 ± 12.7g) weighed significantly more than EtOH rats (292 ± 13.5 g) after 4 weeks of the diet. There were no other significant differences in weight between the diet cohorts over the remainder of the study (Fig. 1A, Table 1). The serum protein and packed cell volume were not significantly different within or between diet cohorts at any time during the study. Similarly, epididymal fat weight was not significantly different between cohorts or across time points (Fig. 1B), though the mean weight of epididymal fat was higher in the control cohort at each time point. Additionally, the fat from EtOH rats had a translucent versus a loculated appearance and was more friable than control animals. Serum ethanol concentrations in EtOH rats after 4 (21.6 ± 4.13 mmol/L), 8 (32.7±6.46 mmol/L), and 12 (36.2±3.49 mmol/L) weeks were greater than the human intoxication level of 17.4 mmol/L.

Figure 1.

Mean ± SEM rat weight (A) and epididymal adipose weight (B) after 4, 8, or 12 weeks of a 37% EtOH or isocaloric liquid diet. * = Significant difference between diet cohorts within time points.

Table 1.

Weekly diet consumption, animal weight, and ethanol consumption (mean ± SEM) for rats on a 36% EtOH (treatment) or isocaloric (control) liquid diet

| Diet Intake (ml) | Weight (g) | Ethanol Intake (g/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Treatment | |

| 1 | 68.4 ± 5.14 | 67.8 ± 4.83 | 266 ± 7.56 | 246 ± 7.07 | 99.0 ± 6.82 | |

| 2 | 93.8 ± 4.27 | 78.6 ± 1.76 | 284 ± 6.43 | 257 ± 6.95 | 110 ± 2.53 | |

| 3 | 84.4 ± 6.28 | 75.4 ± 3.69 | 318 ± 5.52 | 271 ± 6.13 | 100 ± 6.02 | |

| 4 | 77.4 ± 2.08 | 86.1 ± 4.23 | 326 ± 12.7 | 292 ± 13.5 | 106 ± 3.13 | |

| 5 | 71.1 ± 0.540 | 84.0 ± 3.18 | 341 ± 5.85 | 312 ± 6.45 | 96.8 ± 4.94 | |

| 6 | 71.7 ± 0.63 | 87.1 ± 3.89 | 352 ± 4.43 | 330 ± 3.31 | 94.9 ± 11.7 | |

| 7 | 72.9 ± 0.366 | 88.2 ± 3.09 | 360 ± 4.41 | 341 ± 4.62 | 93.0 ± 6.68 | |

| 8 | 74.1 ± 0.296 | 89.9 ± 2.30 | 380 ± 10.3 | 371 ± 5.68 | 87.2 ± 4.04 | |

| 9 | 75.9 ± 0.569 | 82.7 ± 2.28 | 396 ± 2.97 | 370 ± 2.70 | 80.4 ± 8.44 | |

| 10 | 84.7 ± 1.70 | 82.0 ± 2.74 | 406 ± 4.60 | 372 ± 3.92 | 79.2 ± 6.98 | |

| 11 | 85.9 ± 0.78 | 83.7 ± 3.23 | 417 ± 4.75 | 388 ± 5.20 | 72.2 ± 6.79 | |

| 12 | 82.6 ± 2.27 | 87.2 ± 2.92 | 432 ± 3.07 | 424 ± 2.82 | 74.0 ± 10.4 | |

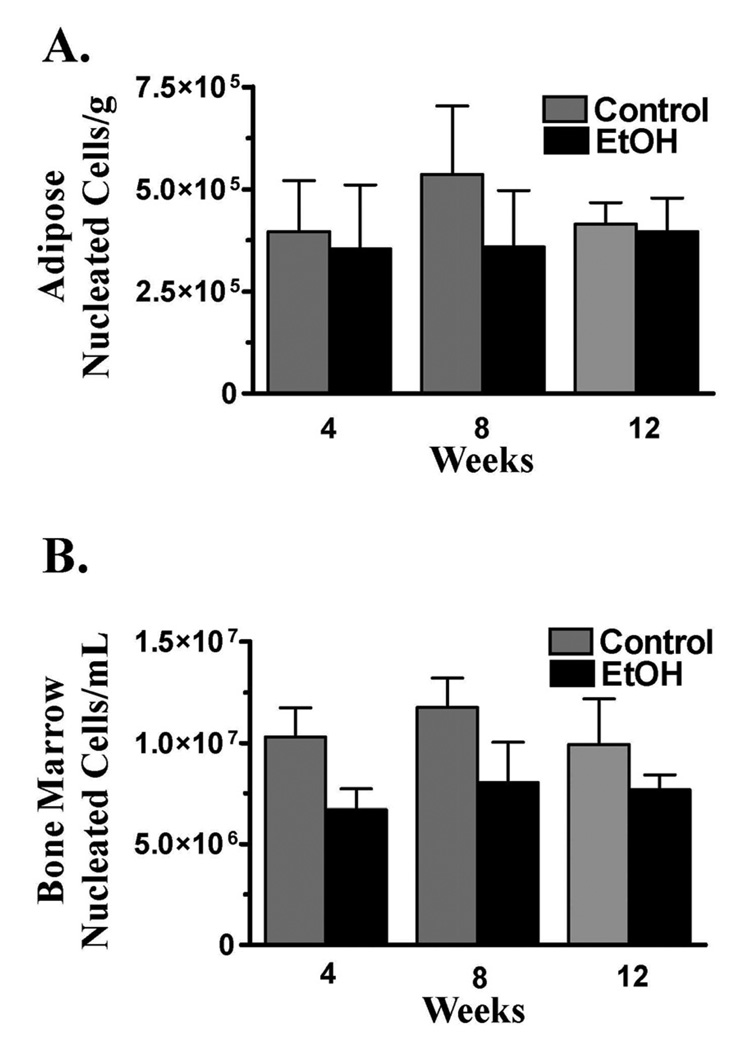

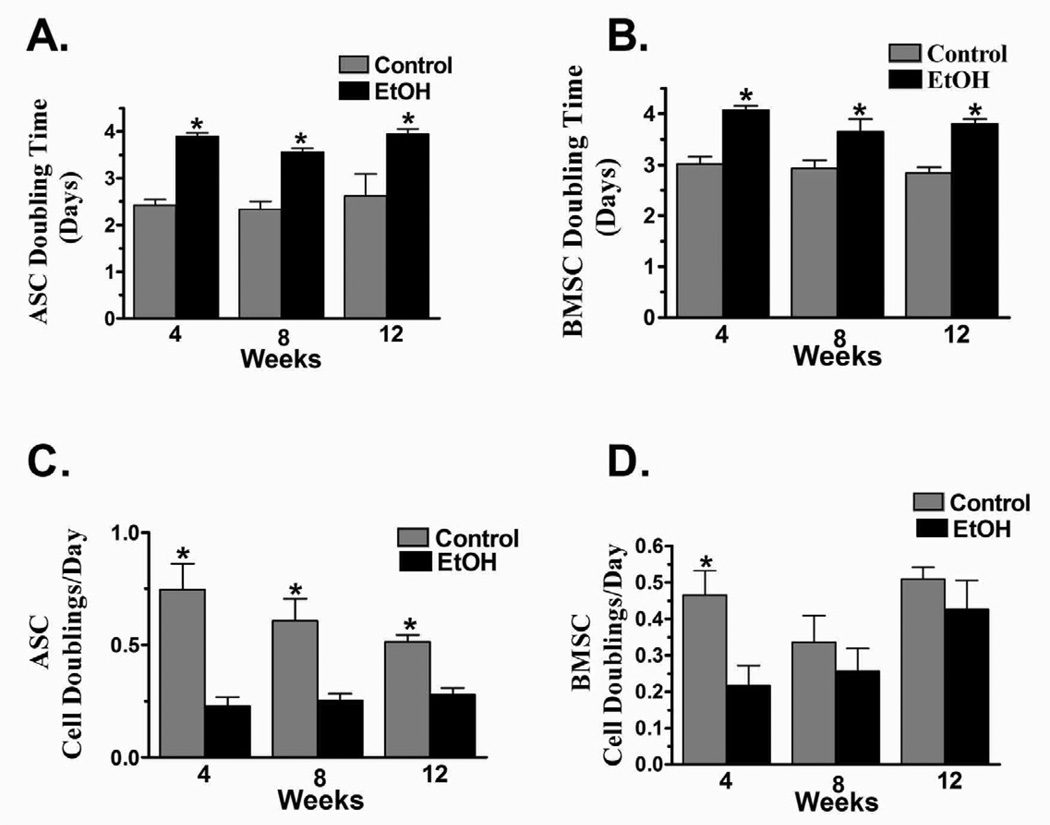

There were no differences between cohorts in the number of nucleated cells harvested from adipose or bone marrow at any point during the study (Fig. 2) The DTs for ASCs harvested from control rats was significantly lower than that for those harvested from EtOH rats after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of the diet (Fig. 3A–B). The CDs were significantly higher for control ASCs compared to EtOH cohorts at each time point, but, though higher, the CDs where not significantly different between BMSC diet cohorts after 8 or 12 weeks (Fig. 3 C–D).

Figure 2.

Number of nucleated cells (mean ± SEM) harvested from epididymal adipose (A) or combined femoral and tibial bone marrow (B) after 4, 8, or 12 weeks of a 37% EtOH or isocaloric liquid diet. * = Significant difference between diet cohorts within time points.

Figure 3.

Mean ± doubling time and cell doublings/day for ASCs (A, C) and BMSCs (B, D) after 4, 8, or 12 weeks of a 37% EtOH or isocaloric liquid diet. * = Significant difference between diet cohorts within time points.

Cells cultured in osteogenic and adipogenic media developed calcified colonies and intracellular lipid droplets, respectively, as anticipated while those in stromal media did not undergo any phenotypic changes detectable with light microscopy. The CFU-F, CFU-Ad CFU-Ob were significantly higher for ASCs harvested from control versus EtOH rats for P0, P3 and P6 after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of the diet (Table 2). The P0 CFU-Ad and CFU-Ob and P3 CFU-Ob were significantly higher for BMSCs harvested from control versus EtOH rats after 12 weeks of the diet while the P3 CFU-Ob was significantly higher in control BMSCs after 8 weeks on the diet. Effects of diet duration on CFU frequencies were significant in the ASC EtOH diet cohort (Table 2). Specifically, the CFU-F was significantly lower after 12 weeks of the diet compared to 4 and 8 weeks in all three passages evaluated. The ASC CFU-Ad was significantly lower after 12 weeks compared to 4 and 8 weeks, and after 8 weeks compared to 4 weeks in P3 and P6, respectively. The CFU-Ob was significantly lower after 12 weeks compared to 4 and 8 weeks in P0, and P6 week 12 CFU-Ob was significantly lower than week 8 which was in turn significantly lower than week 4.

Table 2.

Colony forming unit frequencies (mean ± SEM) following culture in stromal (CFU-F), adipogenic (Ad), and osteogenic (Ob) induction media for adult adipose derived (ASC) and bone marrow derived (BMSC) stromal cells harvested from adult rats after 4, 8, or 12 weeks of a liquiddiet containing 36% EtOH or an isocaloric substitution of maltodextrose. All results are reported as ratios of one CFU per the indicated number of cells.

| Colony Forming Unit Frequency | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passage | 0 | 3 | 6 | ||||||||

| Week | Cell Type | Diet Cohort | CFU-F | CFU-Ad | CFU-Ob | CFU-F | CFU-Ad | CFU-Ob | CFU-F | CFU-Ad | CFU-Ob |

| 4 | ASC | Control | 16.3 ± 2.50* | 17.9 ± 1.38* | 16.8 ± 2.39* | 16.9 ± 3.16* | 23.2 ± 1.35* | 19.9 ± 2.34* | 30.6 ± 2.06* | 37.1 ± 9.82* | 32.3 ± 5.12* |

| 4 | ASC | EtOH | 36.1 ± 5.95a | 60.1 ± 12.4 | 43.2 ± 5.19a | 59.3 ± 11.5a | 60.5 ± 12.2a | 42.6 ± 7.22 | 55.7 ± 7.50a | 62.0 ± 12.0a | 53.6 ± 8.85a |

| 4 | BMSC | Control | 346 ± 11.9 | 357 ± 14.6 | 124 ± 10.0 | 404 ± 11.7 | 428 ± 36.9 | 165 ± 12.1 | 383 ± 11.9 | 411 ± 43.9 | 372 ± 55.6 |

| 4 | BMSC | EtOH | 452 ± 36.7 | 383 ± 11.9 | 149 ± 15.1 | 417 ± 24.0 | 470 ± 82.0 | 224 ± 42.6 | 464 ± 27.0 | 509 ± 1.02 | 468 ± 91.5 |

| 8 | ASC | Control | 28.0 ± 11.7* | 24.2 ± 4.01* | 23.9 ± 1.72* | 27.3 ± 3.14* | 27.0 ± 2.38* | 31.4 ± 2.35* | 20.1 ± 1.54* | 35.4 ± 4.40* | 28.5 ± 1.38* |

| 8 | ASC | EtOH | 49.5 ± 10.3a | 76.6 ± 18.5 | 74.4 ± 7.68a | 65.6 ± 6.91a | 78.5 ± 6.42a | 71.4 ± 2.17 | 77.3 ± 18.4a | 80.1 ± 5.92b | 76.1 ± 7.17b |

| 8 | BMSC | Control | 328 ± 5.89 | 446 ± 25.7 | 339 ± 13.6 | 316 ± 6.94 | 441 ± 27.8 | 331 ± 51.7* | 336 ± 2.71 | 485 ± 23.4 | 375 ± 41.6 |

| 8 | BMSC | EtOH | 402 ± 30.9 | 552 ± 76.6 | 399 ± 32.1 | 437 ± 29.4 | 488 ± 21.1 | 485 ± 23.3 | 441 ± 29.4 | 485 ± 23.2 | 431 ± 33.6 |

| 12 | ASC | Control | 51.5 ± 2.41* | 127 ± 13.3* | 78.5 ± 3.51* | 64.6 ± 19.4* | 85.0 ± 11.0* | 121 ± 12.1* | 98.0 ± 17.4* | 202 ± 18.5* | 93.3 ± 8.40* |

| 12 | ASC | EtOH | 343 ± 68.0b | 448 ± 35.9 | 355 ± 58.5b | 896 ± 61.1b | 448 ± 35.9b | 362 ± 60.0 | 859 ± 91.7b | 523 ± 67.2a/b | 452 ± 65.4c |

| 12 | BMSC | Control | 647 ± 7.45 | 552 ± 65.9* | 561 ± 78.8* | 616 ± 14.7 | 712 ± 44.2 | 552 ± 54.11* | 593 ± 63.8 | 743 ± 30.4 | 613 ± 29.1 |

| 12 | BMSC | EtOH | 756 ± 29.2 | 800 ± 83.11 | 754 ± 18.0 | 737 ± 21.1 | 768 ± 32.4 | 742 ± 33.0 | 767 ± 18.8 | 779 ± 58.9 | 775 ± 26.0 |

Significant differences between diet cohorts within cell passages, time points, and lineages. Different letter superscripts within cell type, diet, and lineage indicate significant differences among time points (p < 0.05).

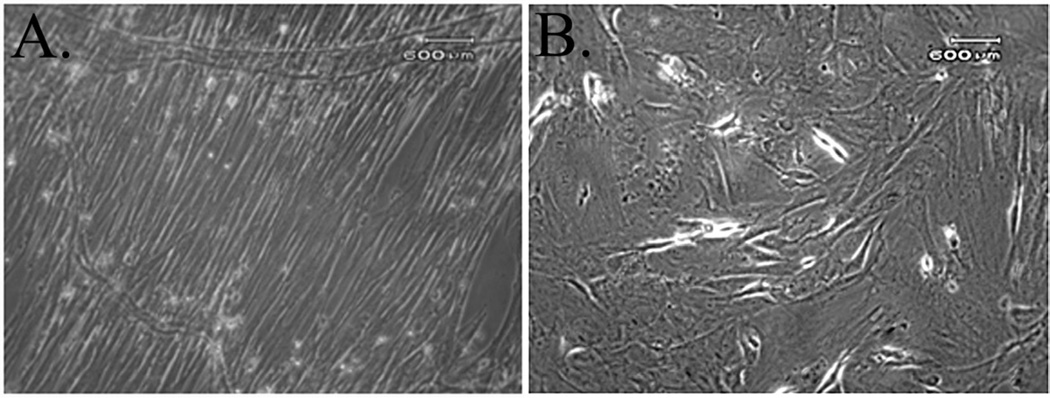

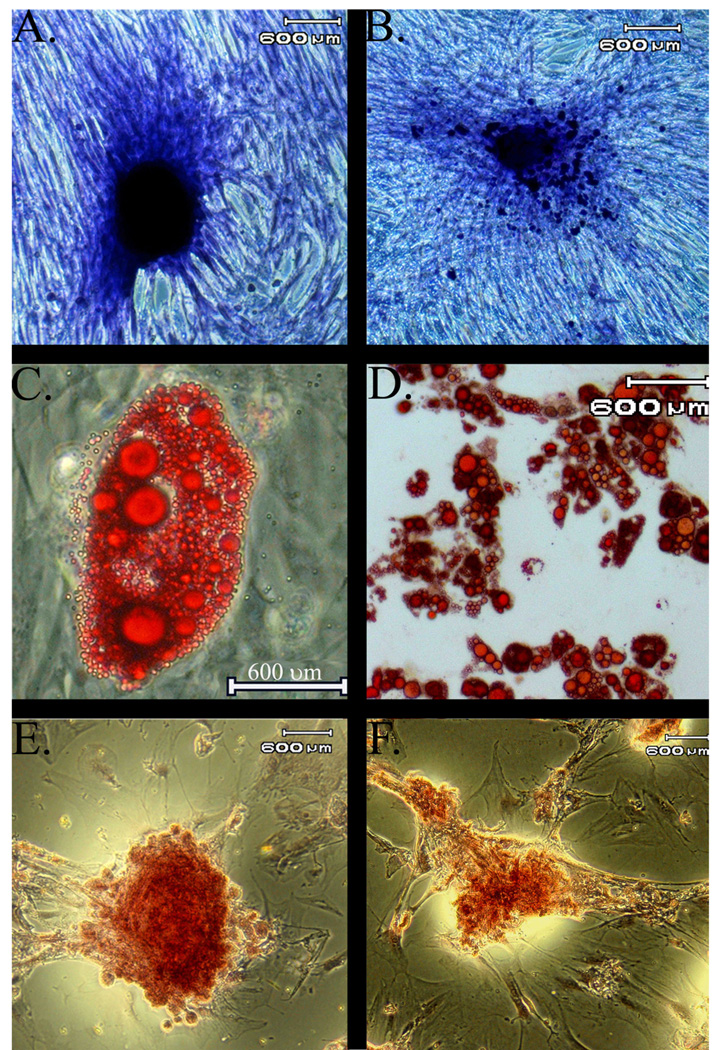

In addition to differences in CFU-F frequencies between diet cohorts, there were distinct differences in cell morphology (Fig. 4 A–B). The P0 adipose isolates from control rats at each time point were heterogenous, displaying both an elongated, spindle like morphology characteristic of a fibroblast phenotype and a flattened, polygonal shape with short or absent processes. The P0 adipose isolates from EtOH rats had less heterogenous P0 populations, and the majority of cells had a flattened polygonal shape. At each passage, colonies were apparent after 7 days in both cell types, and over the next 10 days, control ASC colonies increased in size while EtOH ASC colonies grew more slowly. As supported by the CFU-F data above, control ASCs had more plastic adherent cells for a given seeding density that subsequently developed into more colonies than EtOH ASCs after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of the diet for each passage (Fig. 5A–B).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs depicting different morphology between P0 ASCs harvested from control (A) versus EtOH (B) rats. The P0 adipose isolates from control rats at each time point were heterogenous, displaying both an elongated, spindle like morphology characteristic of a fibroblast phenotype and a flattened, polygonal shape with short or absent processes. The P0 adipose isolate from EtOH rats had less heterogenous P0 populations, and the majority of cells had a flattened polygonal shape.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of ASCs harvested from control (left) and EtOH rats (right) following culture in stromal (A,B), adipogenic (C,D), or osteogenic (E,F) media. Colonies from EtOH ASCs were smaller and less organized than those from control ASCs. Staining toluidine blue (A,B), Oil Red O (C,D), Alizarin Red (E,F).

Intracellular lipid droplets were apparent in all passages of control and EtOH ASCs after 3 days in adipogenic induction media at each time point. As in the CFU-F cultures, there were fewer plastic adherent cells in the EtOH ASCs for a given seeding density and subsequently fewer colonies. Lipid droplets increased in size and number with time in control ASCs (Fig. 5C–D), but the number and size did not increase to the same degree in EtOH ASCs when cells were cultured in adipogenic medium. Similarly, ASCs cultured in osteogenic medium went from a thin, elongated to an oval shape and aggregated into distinct colonies that stained positive for calcium for all passages and time points (Fig. 5E–F). Again, as evidenced by the CFU-Ob data above, there were fewer plastic adherent cells in EtOH ASCs, fewer colonies, and the colonies were smaller and less organized that control ASCs.

Discussion

Based on the results of this study, chronic, high dose EtOH ingestion negatively impacts in vitro expansion rates and multipotentiality of adult stromal cells in a rat model. Increased cell doubling times were apparent throughout multiple cell passages in ASCs and BMSCs from EtOH consumption cohorts. Inhibition of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation that increased with longer EtOH ingestion was most evident in ASCs, though effects were also apparent in BMSCs. A novel aspect of this investigation was that EtOH effects on two types of adult stromal cells from the same individuals following systemic exposure were determined in contrast to a number of studies in which direct in vitro EtOH application was evaluated. The model permits a direct assessment of variable periods of high dose EtOH ingestion on distinct adult stromal cell populations within individuals. Though not directly analogous, the information likely mirrors the in vivo health and potential of the stromal cells within the limits of an in vitro culture system. The results of this study support that high dose EtOH ingestion has detrimental effects on adult stromal cells.

The fact that the reduced expansion rate of both types of stromal cells was maintained up to 6 passages in vitro after as early as 4 weeks of high dose alcohol ingestion suggests potential mitotic inhibition. Assumptions inherent to DT determination are that all cells are dividing, have the same cycle times, and are uniformly distributed in the cell cycle. Observed increases in DTs may be a result of changes in one or all of these parameters. The DTs and associated CDs for control cells in this study are consistent with published information for adult rat ASCs (Arrigoni et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2008) and BMSCs (Neuhuber et al., 2008) making it unlikely that the liquid diet reduced the in vitro expansion capacity. Comparisons within this manuscript are limited to the paired observations reported here since plating density and culture conditions significantly affect doubling times (Arrigoni et al., 2009; Neuhuber et al., 2008). Greater reductions in cell expansion capacity with increased duration of alcohol ingestion may have been observed with a longer study design or a later observation point. The significantly longer stromal cell DTs from the EtOH cohorts in this study could account for delayed healing and poor tissue homeostasis observed in alcoholic patients.

The number of nucleated cells harvested from bone marrow or adipose was not significantly different between cohorts at any time point, despite a lower mean weight in the EtOH cohort after 4 weeks on the diet. The nucleated cell harvest does not represent the number of progenitor cells, but rather a cell population from which a heterogeneous population of progenitor cells is selected based on plastic affinity and culture conditions (Alhadlaq and Mao, 2004; Neubauer et al., 2004; Santa et al., 2004). The CFU-F, a representation of the actual potential progenitor cell frequency, was significantly lower in ASCs from EtOH cohorts for all passages and time points, though it was never different between BMSC diet cohorts. The number and potential of adult stromal cells varies with the parent tissue as well as the harvest location for a given tissue (Yoshimura et al., 2007). Effects of EtOH also vary between tissue types and within the same tissue at different anatomical sites (Kim et al., 2003). It is therefore not surprising that progenitor cell numbers from different tissues are variably affected by a high dose EtOH diet. Epididymal adipose was evaluated in this study since it is the purest white adipose tissue (WAT) depot (Petrovic et al., 2009), and it is an established animal model to evaluate the effects of alcohol consumption on WAT (Feng et al., 2008; Pravdova et al.; 2009, Yu et al., 2010,). White adipose tissue is also a highly active metabolic tissue (Pravdova and Fickova, 2006) that contains stromal vascular cells (Federico, et al, 2010), and visceral adipose is a more potent adverse metabolic risk agent than subcutaneous adipose tissue (Yu et al, 2010). Passage effects were not evident in this study, though decreased multipotentiality and cell proliferation has been reported for rat adult stromal cells between passages 5 and 10 (Lim et al., 2006; Yoshimura et al., 2007). Passage effects may have become evident with higher passage numbers.

Adult stromal cells from adipose tissue and bone marrow are critical for normal tissue maintenance, regeneration, and repair and progenitor cells from both undergo osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo (Tapp et al., 2008). The adipocyte is the most abundant stromal cell phenotype in adult bone marrow (Wezeman and Gong, 2001). Alcohol consumption is known to increase bone marrow adiposity in vivo (Maddalozzo et al., 2009) and the lineage commitment and differentiation of BMSCs toward the adipogenic pathway is promoted by alcohol in vitro (Wezeman and Gong, 2004). Delayed bone healing and osteoporosis have been attributed to this observed shift toward adipogenesis based on an apparent reciprocal relationship between osteogenesis and adipogenesis (Wezeman and Gong, 2004), although recent findings challenge this paradigm (Gimble et al., 2006). There is a high degree of transdifferentiation between marrow osteoblasts and adipocytes that suggests their derivation from a common multipotential precursor (Park et al., 1999). Hence, it is possible that preadipocytes contribute to bone formation and maintenance, and that inhibition of ASC osteogenesis by EtOH ingestion may contribute to abnormal bone maintenance and healing. The significantly reduced osteogenic capacity of P0 and P3 BMSCs after 12 weeks in the EtOH cohort and P3 BMSCS after 8 weeks are consistent with osteogenic inhibition of stromal cells that likely reflects the in vivo situation (Hausman et al., 2008).

Primary rat adult stromal cell isolates consist of a morphologically heterogenous population with two major subpopulations: 1) spindle-shaped cells with processes that extend in opposite directions from the cell body, and 2) flat, polygonal cells with or without short processes (Neuhuber et al., 2008). After several passages, the heterogenous population evolves into a tightly packed, homogenous spindle-shaped population. As the cells lose multipotential with increasing passages in vitro, the majority assume a large, flat, polygonal shape (Lim et al., 2006; Neuhuber et al., 2008). In this study, all primary ASC isolates from EtOH rats had fewer spindle shaped cells, and a disproportionate amount of polygonal cells when compared to those from control rats. The altered cell phenotype population ratio may account for the smaller and less organized adipogenic and osteogenic colony formation. Since the morphology was apparent in primary isolates of EtOH ASCs, it appears to mirror the in vivo stromal cell population. The EtOH ASCs consistently had impaired multipotentiality in vitro, so the population shift may indicate loss of or reduced multipotentiality in vivo due to cell senescence and/or loss of inherent “stem cell” properties.

The composition and distribution of adipose tissue is altered by alcohol consumption (Alhadlaq and Mao, 2004; Maddalozzo et al., 2009). Though paired weights were not significantly different beyond 4 weeks of EtOH ingestion in this study, epididymal fat was less abundant and subjectively less dense in the EtOH cohort at each time point. The weight difference between diet cohorts after 4 weeks may reflect a period of diet acclimation since differences were not apparent after 8 or 12 weeks. As noted above, there were no differences in nucleated cells in the harvested, digested adipose tissue between cohorts, but the CFU-F was significantly lower in the EtOH cohort as were the CFU-Ad and CFU-Ob throughout the study. The lower number and multipotentiality of ASCs in EtOH animals may well reflect a compromised ability of adipose tissue to repair and regenerate in vivo.

The EtOH effect on ASCs after only 4 weeks in the EtOH cohort that was maintained up to 6 cell passages in this investigation suggests that EtOH has a greater effect on ASCs than BMSCs. This is further supported by the greater impact of diet exposure time on the ASC CFU frequencies compared to BMSC CFU frequencies. The apparent differences in sensitivity to alcohol ingestion between progenitor cell types may be related to the heterogenic cell populations evaluated (Böhrnsen et al., 2009) as well as the variable effects of alcohol on the metabolism of the parent tissue source. Chronic ethanol exposure in rats increases the rate of triglyceride degradation in adipose tissue and decreases glucose uptake in adipocytes (Yu et al., 2010). As indicated above, the predominant ASC phenotype isolated from EtOH rats in this study was most consistent with that of mature cells with less potential than the spindle shaped ASCs isolated from the control rats (Neuhuber et al., 2008). It is possible that the high dose alcohol ingestion in this study reduced the number of immature, multipotent cells in the adipose tissue and that the effect increased with time of exposure, potentially due to greater metabolic impact on adipose; however, evaluation of the metabolic changes in adipose was beyond the purview of this study. Mechanisms by which in vivo alcohol ingestion impairs in vitro stromal cell multipotentiality are the basis for future investigations.

The effects of chronic, high dose alcohol consumption on native stromal cell function have direct relevance to the mechanisms underlying the impaired bone formation in alcoholic patients and provide a promising target for therapeutic intervention. The current study design permitted evaluation of the effects of high dose EtOH ingestion on distinct adult stromal cell populations within individuals and between diet pairs. The results conclusively show significant inhibitory effects of high dose alcohol ingestion on native stromal cell capacity in vitro. It will be important to evaluate in vivo stromal cell behavior under comparable conditions. Further studies will also be toned to evaluate the potential for stromal cell recovery by alcohol cessation or therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by NIH-NIAAA Grants R15 # AA017546 (NKH, NDS, MJL) and ARC #AA09803 (NKH, SN, GJB, MJL)

The authors are grateful to Yanru Zhang and Lin Xie for technical assistance and to Michael Kearney for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alhadlaq A, Mao JJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation and therapeutics. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:436–448. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigoni E, Lopa S, de Girolamo L, Stanco D, Brini AT. Isolation, characterization and osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells: from small to large animal models. Cell Tissue Res. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellows CG, Aubin JE. Determination of numbers of osteoprogenitors present in isolated fetal rat calvaria cells in vitro. Dev. Biol. 1989;33:8–13. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhrnsen F, Lindner U, Meier M, Gadallah A, Schlenke P, Hendrik L, Rohwedel J, Kramer J. Murine mesenchymal progenitor cells from different tissues differentiated via mesenchymal microspheres into the mesodermal direction. 2009;10:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakkalakal DA, Novak JR, Fritz ED, Mollner TJ, McVicker DL, Lybarger DL, McGuire MH, Donohue TM., Jr Chronic ethanol consumption results in deficient bone repair in rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:13–20. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JR, Shankar K, Nagarajan S, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. Protective effects of estradiol on ethanol-induced bone loss involve inhibition of reactive oxygen species generation in osteoblasts and downstream activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3/receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand signaling cascade. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:50–59. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CM, Aalami OO, Shi YY, Chou YF, Mari C, Thomas R, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 and retinoic acid accelerate in vivo bone formation, osteoclast recruitment, and bone turnover. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:645–658. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CM, Shi YY, Aalami OO, Chou YF, Mari C, Thomas R, et al. Adipose-derived adult stromal cells heal critical-size mouse calvarial defects. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:560–567. doi: 10.1038/nbt958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Wang Y, Saleh KJ, Wang GJ, Balian G. Alcohol-induced adipogenesis in a cloned bone-marrow stem cell. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;88 Suppl 3:148–154. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer SA, Buckendahl P, Sampson HW. Alcohol consumption inhibits osteoblastic cell proliferation and activity in vivo. Alcohol. 1998;16:337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federico A, D’Aiuto E, Borriello F, Barra G, Gravina AG, Romano M, De Palma R. Fat: a matter of disturbance for the immune system. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4762–4772. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i38.4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Gao L, Guan Q, Hou X, Wan Q, Wang X, Zhao J. Long-term moderate ethanol consumption restores insulin sensitivity in high-fat-fed rats by increasing SLC2A4 (GLUT4) in the adipose tissue by AMP-activated protein kinase activation. J Endocrin. 2008;199:95–104. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble J, Guilak F. Adipose-derived adult stem cells: isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:362–369. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA. Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Circ. Res. 2007;100:1249–1260. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble JM, Zvonic S, Floyd ZE, Kassem M, Nuttall ME. Playing with bone and fat. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;98:251–266. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Wezeman FH. Inhibitory effect of alcohol on osteogenic differentiation in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:468–479. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000118315.58404.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reimers E, Duran-Castellon MC, Martin-Olivera R, Lopez-Lirola A, Santolaria-Fernandez F, de la Vega-Prieto MJ, et al. Effect of zinc supplementation on ethanol-mediated bone alterations. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005;43:1497–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman DB, Park HJ, Hausman GJ. Isolation and culture of preadipocytes from rodent white adipose tissue. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;456:201–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-245-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicok KC, Du Laney TV, Zhou YS, Halvorsen YD, Hitt DC, Cooper LF, et al. Human adipose-derived adult stem cells produce osteoid in vivo. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:371–380. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justesen J, Pedersen SB, Stenderup K, Kassem M. Subcutaneous adipocytes can differentiate into bone-forming cells in vitro and in vivo. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:381–391. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Shim MS, Kim MK, Lee Y, Shin YG, Chung CH, et al. Effect of chronic alcohol ingestion on bone mineral density in males without liver cirrhosis. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2003;18:174–180. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2003.18.3.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Padmanabhan P, Ray P, Gambhir SS, Doyle T, Contag C, et al. Stem cell-mediated accelerated bone healing observed with in vivo molecular and small animal imaging technologies in a model of skeletal injury. J. Orthop Res. 2009;27:295–302. doi: 10.1002/jor.20736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon DP, Caplan AI. Isolation of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Hematol. 2006;34:1606–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JY, Jeun SS, Lee KJ, Oh JH, Kim SM, Park SI, et al. Multiple stem cell traits of expanded rat bone marrow stromal cells. Experimental Neurology. 2006;199:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MJ, McIntosh KR, Spencer ND, Borneman JN, Horswell R, Anderson P, et al. Acceleration of spinal fusion using syngeneic and allogeneic adult adipose derived stem cells in a rat model. J. Orthop. Res. 2009;27:366–373. doi: 10.1002/jor.20735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddalozzo GF, Turner RT, Edwards CH, Howe KS, Widrick JJ, Rosen CJ, et al. Alcohol alters whole body composition, inhibits bone formation, and increases bone marrow adiposity in rats. Osteoporos. Int. 2009;20:1529–1538. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0836-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh KR, Lopez MJ, Borneman JN, Spencer ND, Anderson PA, Gimble JM. Immunogenicity of Allogeneic Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in a Rat Spinal Fusion Model. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2009 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2008.0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer M, Fischbach C, Bauer-Kreisel P, Lieb E, Hacker M, Tessmar J, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor enhances PPARgamma ligand-induced adipogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhuber B, Swanger SA, Howard L, Mackay A, Fischer I. Effects of plating density and culture time on bone marrow stromal cell characteristics. Exp. Hematol. 2008;36:1176–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PC, Selvarajah S, Bayani J, Zielenska M, Squire JA. Stem cell enrichment approaches. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2007;17:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SR, Oreffo RO, Triffitt JT. Interconversion potential of cloned human marrow adipocytes in vitro. Bone. 1999;24:549–554. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct fromm classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7153–7164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravdova E, Fickova M. Alcohol intake modulates hormonal activity of adipose tissue. Endocr Regul. 2006;40:91–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravdova E, Macho L, Fickova M. Alcohol intake modifies leptin, adiponectin and resistin serum levels and their mRNA expressions in adipose tissue of rats. Endocr Regul. 2009;43:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainaldi G, Pinto B, Piras A, Vatteroni L, Simi S, Citti L. Reduction of proliferative heterogeneity of CHEF18 Chinese hamster cell line during the progression toward tumorigenicity. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. 1991;27A:949–952. doi: 10.1007/BF02631122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa ML, Beloti MM, Prando N, Queiroz RH, de Oliveira PT, Rosa AL. Chronic ethanol intake inhibits in vitro osteogenesis induced by osteoblasts differentiated from stem cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2008;28:205–211. doi: 10.1002/jat.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi Y, Sekiya I, Yagishita K, Muneta T. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues: superiority of synovium as a cell source. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2521–2529. doi: 10.1002/art.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa ML, Rojas CV, Minguell JJ. Signals from damaged but not undamaged skeletal muscle induce myogenic differentiation of rat bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;300:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgodda M, Aurich H, Kleist S, Aurich I, Konig S, Dollinger MM, et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from rat peritoneal adipose tissue in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:2875–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapp H, Hanley EN, Patt JC, Gruber HE. Adipose-Derived Stem Cells: Characterization and Current Application in Orthopaedic Tissue Repair. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood.) 2008 doi: 10.3181/0805/MR-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasso R, Augello A, Boccardo S, Salvi S, Carida M, Postiglione F, et al. Recruitment of a Host's Osteoprogenitor Cells Using Exogenous Mesenchymal Stem Cells Seeded on Porous Ceramic. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2009 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholpady SS, Katz AJ, Ogle RC. Mesenchymal stem cells from rat visceral fat exhibit multipotential differentiation in vitro. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell Evol. Biol. 2003;72:398–402. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisiol CH, Turner RT, Pfaff JE, Hunter JC, Menagh PJ, Hardin K, et al. Impaired osteoinduction in a rat model for chronic alcohol abuse. Bone. 2007a;41:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisiol CH, Turner RT, Pfaff JE, Hunter JC, Menagh PJ, Hardin K, et al. Impaired osteoinduction in a rat model for chronic alcohol abuse. Bone. 2007b;41:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal MA, Kilroy GE, Johnson JR, Lopez MJ, Moore RM, et al. Cell growth characteristics and differentiation frequency of adherent equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: adipogenic and osteogenic capacity. Vet. Surg. 2006;35:601–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2006.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wezeman FH, Gong Z. Bone marrow triglyceride accumulation and hormonal changes during long-term alcohol intake in male and female rats. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:1515–1522. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wezeman FH, Gong Z. Adipogenic effect of alcohol on human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:1091–1101. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130808.49262.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Prasad HS, Rohrer MD, Gimble JM. Frequency of stromal lineage colony forming units in bone marrow of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-null mice. Bone. 2000;26:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Liu Z, Liu L, Zhao C, Xiong F, Zhou C, et al. Neurospheres from rat adipose-derived stem cells could be induced into functional Schwann cell-like cells in vitro. BMC. Neurosci. 2008;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura H, Muneta T, Nimura A, Yokoyama A, Koga H, Sekiya I. Comparison of rat mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, synovium, periosteum, adipose tissue, and muscle. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:449–462. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0308-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HC, Cao MF, Jiang XY, Feng L, Zhao JJ, Gao L. Effects of chronic ethanol consumption on levels of adipokines in visceral adipose tissues and sera of rats. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2010;31:461–469. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]