Abstract

Esthetic replacement and physiological tooth arrangement made the complete denture biologically compatible and desirable. Proper placement of tooth should be functional and esthetically pleasing to enhance the psychology of the patient. This article reviews the evolution of concepts for teeth selection and the recent techniques employed for selecting anterior teeth for complete dentures.

Keywords: Esthetics, Selection, Teeth

Introduction

Esthetics is the primary consideration for patients seeking prosthetic treatment. The size and form of the maxillary anterior teeth are important not only to dental esthetics but also to facial esthetics. The goal is to restore the maxillary anterior teeth in harmony with the facial appearance. However, there is little scientific data in the dental literature to use as a guide for defining the proper size and shape of anterior teeth or determining normal relationships for them [1]. According to Young “it is apparent that beauty, harmony, naturalness, and individuality are major qualities” of esthetics [2].

History of Anterior Teeth Selection

During the ivory age, teeth were selected, mostly by dimensional measurements, with slight consideration given to face form or other qualities.

The geometric classification of face form and profile, which was projected by Madame Schimmelpeinik in 1815 for artists use was considered in dentistry for esthetic teeth selection. The “correspondence and harmony” concept was projected by J.W. White in 1872. The basis of this concept was that the temperaments called for a characteristic association of the tooth form and color, and that harmony called for a corresponding proportion and size of tooth to that of the face, and a tooth color in harmony with facial complexion; that both form and color were modified to be in harmony with sex and age. The dentist problem was to correlate and supplement these various field values into a dental temperamental classification useful for selecting the tooth mould.

The “Temperamental technic” of selecting tooth form should be considered the fourth technique chronologically yet the first technique from the point of view of influence and universal acceptance [3]. The “Typal form concept” projected by W.R. Hall in 1887 [4]. Hall gave the first measurements of the typal tooth forms.

“Berry’s biometric ratio method”, was projected in 1906 [5]. He discovered that the proportions of the upper central incisor tooth had a definite proportional ratio to face proportions. The tooth was one sixteenth of the face width and one twentieth the face length.

Clapp’s “Tabular Dimension Table Method,” was presented around 1910 [6]. This method was based on selecting tooth size from the overall dimension of six anterior teeth and the vertical tooth space present in the patient. “Molar Tooth Basis,” was projected by Valderrama in 1913 [7]. According to this method, the tooth size was measured on a one-fourth increment of the size of a Bonwill triangle, and is determined by measuring the edentulous mandible.

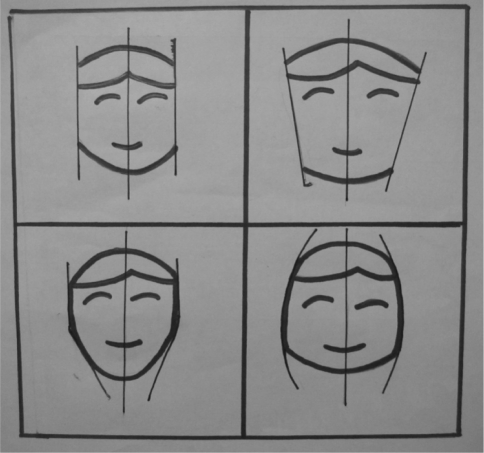

Cigrande in 1913 [8] used the outline form of the fingernail to select the outline form of the upper central incisor tooth. The size was modified to meet the requirements of tooth space and other relationship. Williams “Typal form method,” projected in 1914 [9]. He classified the facial form into square, tapering and ovoid forms (Fig. 1). Later the selection was based on “Mould Guide Sample Teeth”. “Wavrin Instrumental Guide Technique”, projected about 1920, which was a combination of Berry’s Biometric ratio method and the William’s typal form teeth [10].

Fig. 1.

Leon Williams Face Forms

In 1920 Nelson projected a technique for selecting a tooth mould and he called it as “Maxillary Arch Outline Form,” This technique assumed that the arch outline form was the valid method [11]. In 1936 “Wright’s Photometric Method” was projected. This was based on using a photograph of the patient with natural teeth, and establishing a ratio by comparative computation of measurements of like areas of the face and photograph [12].

The “Multiple Choice Method,” projected by Myerson in 1937 [13]. This was based on a need for a selective range in labial surface characteristics of transparent labial and mesial surfaces, varying surface color tone, and characterizations of teeth by time, wear. The “House Instrumental Method” of projecting typal outline and profile silhouettes onto the face by means of a telescopic projector instrument and silhouette form plates [14]. It was projected by House in 1939.

“Stein’s coordinated size technic,” projected in 1940 [15]. This was based on the coronal index of 70–100, commonly used in prosthetics on four model teeth representing the range of maximum frequency of use, and on the common variability in size of individual natural teeth.

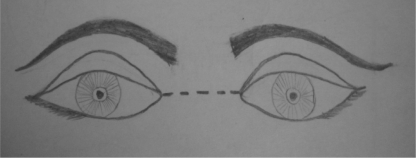

“Anthropometric Cephalic Index Method,” projected by Sears in 1941 [16]. This was based on the fact that width of the upper central incisor could be determined by dividing either the transverse circumference of the head by 13 (Fig. 2) or the bizygomatic width by 3.3. The tooth length was in proportion to the face length.

Fig. 2.

Sear’s anthropometric cephalic index method

“Frame Harmony Method,” projected by the Justi Company in 1949 [17]. The basis of the method is the size and proportions of the teeth are in harmony with the general proportions of the skeleton. The overall tooth size is selected by the mathematical formula, one seventeenth the total dimension of the upper and lower bearing areas, with the dimensions of the individual anterior teeth correlated with a developed table of tooth dimensions to give the indicated overall dimension. The “Bioform technic” was projected by Dentists Supply Company in 1950 which is based on the House classification [18]. The “Selection Indicator Instrument method,” projected by the Dentists’ Supply Company, which is correlated with Williams’ and Houses’ typal tooth form theory and the tabular table technic [19].

The “Automatic Instant Selector Guide” of the Austenal company projected in 1951. This technique correlates form, size, and appearance in such a manner that a single reading only is required to select the appropriate tooth mold based on dimensions of denture space and harmony of face and tooth form. The dentogenic concept of teeth selection was put forth by Frush and Fischer in 1955 [20].

Concepts of Teeth Selection

White’s Concept

This method was based on a 5th century BC concept attributed to Hippocrates. Temperamental types were sanguine, nervous, billious and lymphatic named for the physiologic functions of blood, nerves, bile and lymph of the individual. Artificial teeth were arbitrarily selected to suit the patient’s temperament. A “bilious” individual would be expected to have short, broad, tapering incisor teeth, whereas a “sanguineous” individual would possess long, thin, and narrow teeth [21].

H.Pound’s Concept [22]

Evaluates tooth width by “measuring the distance from zygoma to zygoma, one to one half inches back of the lateral corner of the eyes”

|

Length is a measure of the distance from the hairline to the lower edge of the bone of the chin with the face at rest.

|

Dentogenic Concept [23]

Tooth selection using the concepts of dentogenics is based on the age, sex and personality of the patient putforth by Frush and Fisher 1955. This concept has been explained as the prosthodontic appearance interpretation of three vital factors which every patient possess. The factors are sex, personality and age of the patient.

Winkler’s Concept [24]

This concept emphasises on three points. The biological-physiological, biomechanical and the psychological viewpoint. The biological-physiological view point stated the importance of harmony of the facial musculature and physiological limit with teeth arrangement. Biomechanical shows the mechanical limitations in placement of anterior teeth. Psychological view is based on esthetics and facial appearance.

Leon William’s Concept [9]

William formulated a method called the law of harmony. He believed that a relationship exists between the inverted face form and the form of maxillary central incisor in most people. He described three typal forms of teeth as square, tapering, ovoid.

Factors to be Considered in Selecting the Size [25]

Nine anatomical entities are used as guides to select anterior teeth according to size.

Size of the Face The width of the anterior teeth in accordance with the face can be calculated as below.Average width of the maxillary central incisor = 1/16th of the width of the face measured between the zygoma.Combined width of the six maxillary anterior teeth = slightly less than 1/3rd of the bizygomatic breadth of the face.The face bow can be used as a calliper to record the bizygomatic breadth. The trubyte tooth indicator is useful in determining the size of the maxillary central incisors. It can be determined by placing the indicator on the patient’s face, allowing the nose to come through the center triangle. Center the pupil in the eyeslots, and hold the indicator with its central line coinciding with the median line. Slide the side indicator bar until it touches the face and the width of the upper central tooth can be read in millimetres. The length of the tooth can be determined by sliding the bottom indicator bar up to position immediatly underneath the chin with lips at rest and the length of the upper central incisor in millimetres.

Size of the Maxillary Arch The mould selectors are used to make measurements of the maxillary cast. Measurements are made from the crest of the incisive papilla to the hamular notches and from one hamular notch to the opposite side hamular notch. The combined length of the three legs of the triangle in millimetres is used as the selector. The circular slide rule indicates the anterior and posterior tooth size.The universal mould selectors are commonly used. The measurements are made from the midline of the maxillary occlusal rim to the distal of the cuspid eminence. An arrow designates on the selector which mould is indicated. When discrepancies exist between the face size and arch size, the selection of anterior tooth should be governed more by face size than arch size, since resorbed tissue can leave one astray.

Incisive Papilla and the Canine Eminence or the Buccal Frenum If the canine eminences are discernible a line can be placed on the cast at the distal termination of the eminence. If eminences are not discernible attachments of buccal frenum are used as guide. A line placed slightly anterior to the buccal frenum will be distal to the eminence. A flexible ruler is used and the distance between the two canine eminences at their distal side through the anterior of the incisive papilla is measured in millimetres and this measurement gives the combined width of the six anterior teeth.Another method of marking the canine eminence is to place the fabricated occlusal rim in the patient’s mouth and ask the patient to relax with the lips closed. With a sharp marker, mark at the corner of the lips. The vertical line drawn from this mark coincides with the pupil of the eye. The distance between the marks following the contour of the arch marked in millimetres is the combined width of six maxillary anterior teeth.

Maxillomandibular Relations Any disproportion in size between the maxillary and mandibular arches influences the length, width and position of the teeth. This is of importance in class II and class III maxillomandibular relations.

Contour of the Residual Ridge The artificial teeth should be placed to follow the contour of the residual ridges that existed when natural tooth were present. As resorption occurs there is alteration in the contours of the ridge.

Vertical Distance Between the Ridges The length of the teeth is determined by the available space between the existing ridges. It is advisable to use a tooth long enough to eliminate the display of the denture base.

Lips Labial surface of the maxillary anterior teeth supports the relaxed lip. Frequently incisal edges extends inferior to or slightly below the lip margin. When the teeth are in occlusion and lips closed the labial incisal third of the maxillary anterior teeth supports the superior border of the lower lip. In speech, incisal edges of maxillary anterior teeth contacts the lower lip at the junction of the moist and dry surfaces of the vermilion border [26].

Nasal Width as a Guide Boucher [27] and Hoffman et al. [28, 29] referred to the nasal index as a guide to select the anterior teeth as it relates the inter alar width to the space available for setting the anterior teeth.Wehner et al. [30] suggested that the “parallel lines” extended from the lateral surface of the ala of the nose onto the labial surface of the upper occlusal rim could be used to give an estimation of the midline vertical axis of the upper canine teeth.Kern [31] made measurements on 509 dried skulls and found that most of the measurements of nasal width are equal to or within 0.5 mm of the measurements of the four maxillary anterior teeth.Mavroskoufis and G.M. Ritchie [32] gave a formula for the selection of the mesiodistal width of the anterior artificial teeth (A = N + 7 mm) where N is the nasal width.

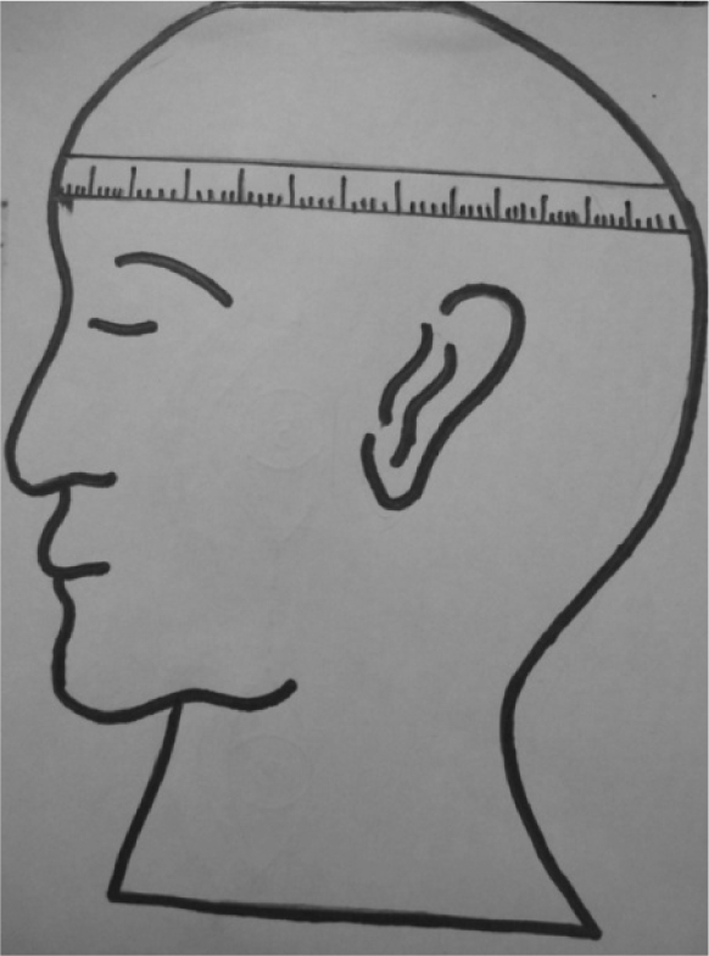

Inner Canthal Distance as a Guide The inner canthal distance (Fig. 3) is defined as the distance between the medial angles of the palpebral fissures [33]. Abdullah in 2002 [34] has proposed a formula to calculate the width of the central incisor from the inner canthal distance. The ICD was found to be greater than the combined width of maxillary central incisors. Thus the ICD was multiplied by 0.618. the resultant product was then divided by 2 to obtain the width of a single central incisor. FCIW = ICD/2 × 0.618.

Fig. 3.

Inter canthal distance

Form of Teeth

Three factors are used as guides in the selection of anterior tooth form.

Form and Contour of the Face The shape of the artificial tooth should harmonise with the patient’s facial form [35]. The classification of tooth forms by Leon Williams, though not scientifically correct, is undoubtedly the simplest and the most useful guide. Leon Williams claimed that the shape of the upper incisors bears a definitive relationship to the shape of the face. He classified the form of the human face into three types: square, tapering and ovoid forms.The operator imagines two lines, one on either side of the face, running about 2.5 cm in front of the tragus of the ear and through the angle of the jaw.

Square––lines are almost parallel

Tapering––lines converge towards the chin

Ovoid––lines diverge towards the chin

The other method of determining the tooth shape is by the use of a trubyte tooth indicator. Place the indicator on the patient’s face, allowing the nose to come through the central triangle. Center the pupils of the eye in the eye slots and hold the indicator with its central line coinciding with the median line of the face.In Square form––the sides of the face will approximately follow the vertical lines of the indicator. In square tapering, the upper third of the lower 2/3rds will taper inward. In tapering faces, the side of the face from the forehead to the angle of the jaw will taper at an inward diagonal. Ovoid faces will be best determined by examination of the curved outline of the face against the straight vertical of the indicator.

Facial Profile To determine the facial profile, observe the relative straightness or curvature. The facial profile is determined by three points. The forehead, the base of the nose and the prominent point of the chin [36].

Straight—three points are in line

Curved—points of the forehead or chin are recessive.

Based on these three points the profile can be straight, convex or concave. The labial surface of the tooth viewed from mesial should show a contour similar to that when viewed in profile. The labial surface of the tooth when viewed from the incisal should show a convexity or flatness similar to that seen when the face is viewed from under the chin or from the top of the head.

Sex Curved facial features are associated with feminity, and square features are associated with masculinity [37]. Since there is harmony between tooth form and face form, it follows that tooth of female are ovoid or tapering than square.

Color of Anterior Teeth

Bilmeyer and Saltzman defined color as the result of the physical modification of light by colorants as observed by the human eye and interpreted by the brain [38]. Light is physical, colorants are chemical, the eye is physiologic, and the brain, of course, is psychologic. Actually, the eye as a receptor interfaced with the brain as an interpreter is psychological in nature. The definition of color is indicative of the variables inherent in seeing and controlling color.

When a tooth is viewed for the purpose of determining its color, two principle colors––yellow and grey––are evident. The yellow is more dominant in the gingival third and the grey is more prominent in the incisal third. The position of the patient and source of light are very important in color selection [38]. The patient should be in upright position. The dentist should be in a position so that the teeth are viewed in a plane perpendicular to the dentist plane of vision. White light of wavelength between 380 and 750 nm in the electromagnetic spectrum is considered suitable. Eyes fatigue to color perception very rapidly, for this reason they should not be focused on a tooth more than few seconds. The teeth and the shade guide should be placed at a distance of 6–8 feet.

Dimensions of Color

The factors controlling color can be controlled into three basic variables: observer variables, object variables and light source variables [39]. This is referred to as geometric metamerism or a conditional color match. The shade of the central incisor has been selected from an appropriate shade guide. In choosing this shade, the dentist should consider the age of the patient, the individual complexion pattern, and the patient’s desires. Acceptable color values of teeth always represent compromises between these three factors. The three dimensions of color are Hue, Value and chroma [40]. Hue describes the dominant color of an object. Value describes the lightness and darkness of a color. Chroma describes the degree of saturation of the particular color. The shade tabs usually includes these three dimensions to help the clinician and the laboratory technician to select an appropriate teeth to match the patient’s appearance.

Light is the origin of color- the primary in the triad of source, object, and observer- it is infrequently considered as such by people viewing color [41, 42]. Incandescent light, which is commonly used in the home and in most operatory lamps, emits a great deal of energy in the red yellow area of the spectrum and very little in the blue area. Therefore if we illuminate samples of red, yellow and blue under the incandescent light source, we will see that the red and yellow are very strong and highly saturated. While the blue is weak and lacking in saturation. Natural day light is considered to be a best source.

Other Pre-Extraction Records as a Guide

Photographs [43], diagnostic casts, teeth of close relatives, pre-extraction intra-oral radiographs and extracted teeth.

Discussion

Happiness is a state of mind. It is brought about by a feeling of well-being, security, harmonious relations with others, and confidence in one’s self. The dentist should render the patient, the confidence that none of these fine senses will be in jeopardy. The development of a pleasing oral and facial expression for the patient depends upon the dentist ability to replace the dentures, both in contour and color [22, 44]. Furnas [45] stated, “esthetics in full denture construction, as employed by at least 90 per cent of the men in general practice, can only said to be conspicuous by its absence.” This statement shows the importance of anterior teeth selection.

Imitating nature with denture involves the application of three basic principles, each one dependent upon the successful application of the others.

The anterior and posterior teeth should be replaced in the same natural position from which they came relative to the lips, the cheeks and the tongue.

The basic anatomy of the dental arches should be fashioned about these teeth in all its natural contours.

The exposed surfaces of the denture should then be tinted by an approved method to more closely imitate the color of living tissue. Color is dependent upon form, and successful color effects can only be made if the contours of the natural basic anatomy are present.

Certain proportion has evolved in history to describe the facial esthetics. Proportion is the study of harmony of structures in space [46–48]. The esthetic proportions are golden proportion [49] which exist from ancient times. Now in the recent years recurrent esthetic proportions are argued [50, 51]. Esthetics may continue to be ignored in favour of the mechanical principles of function, but not without sacrifice of a pleasing and harmonious expression.

Conclusion

Dental art does not occur automatically. It must be purposely and carefully incorporated into the treatment plan by the dentist. This artistry strives to soften the marks imposed upon the face by time and enables people to face their world with renewed enthusiasm and confidence. Art in collaboration with science of denture construction eases the geriatric patient in maintaining physical and psychological health.

References

- 1.Hasanreisoglu U, et al. An analysis of maxillary anterior teeth: facial and dental proportions. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;94:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomes VL, Gonclaves LC, do Prado CJ, et al. Correlation between facial measurements and mesiodistal width of the anterior teeth. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006;18:196–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2006.00019_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapp GW. How the science of esthetic tooth form selection was made easy. J Prosthet Dent. 1955;5:596. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(55)90085-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall WR. Shapes and sizes of teeth in American system of dentistry. Philadelphia: Lea Bros and co; 1887. p. 971. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry FH. Study of prosthetic art. Dent Mag. 1905;1:405. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clapp GW. Twentieth century mold book. New York: Dentist’s Supply co; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valderrama J. Fundamental errors in anatomic articulators. Dent Cosmos. 1913;55:1205–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graber RL. Esthetics of prosthetic dentistry. Dental Review. 1913;27:1085. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JL. A new classification of natural and artificial teeth. New York City: Dentists supply Co; 1914. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wavrin JA. A simple method of classifying face form. Dent Digest. 1920;26:331. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright WH. Selection and arrangement of artificial teeth for complete prosthetic dentures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1936;23:2291–2307. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson AA. The selection of mold and hue of teeth for artificial restoration. Dent Items Interest. 1925;5:775. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mycrson S. A new system for tooth selection. Cambridge: Ideal tooth, Inc; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 14.House MM. Form and color in denture art. Whittier: House and Loop; 1939. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein MF. Williams classification of artificial tooth forms. J Am Dent Assoc. 1936;23:512. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sears VH. Selection of anterior tooth for artificial dentures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1941;28:928. [Google Scholar]

- 17.A manual for plastic teeth (1949) H.D. Justi & sons Inc., Philadelphia, p 8

- 18.Trubyte bioform teeth (1950) Dentist Supply Co, New York City

- 19.Trubyte tooth indicator (1950) Dentist Supply Co, New York City

- 20.Frush JP, Fisher DR. Introduction to dentogenic restorations. J Prosthet dent. 1955;5:586–595. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(55)90084-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young HA. Selecting the anterior tooth mould. J Prosthet dent. 1954;4:748–760. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(54)90041-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pound E. Lost fine arts in the fallacy of ridges. J Prosthet Dent. 1954;4:6–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(54)90060-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frush JP, Fisher RD. The dynesthetic interpretation of dentogenic concept. J Prosthet Den. 1958;8:558–581. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(58)90043-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Land LS. Anterior tooth selection and guidelines complete denture esthetics. In: Winkler S, editor. Essentials of complete denture prosthodontics. 2. St. Louis: Ishiyaku Euro America Inc.; 1996. pp. 200–216. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heartwell CM, Rohn AO (2002) Tooth selection. In: Textbook of complete dentures, 5th ed. BC Decker, pp 305–319

- 26.Alexander LM. Clinical applications of concepts of functional anatomy and speech science to complete denture Prosthodontics. J prosthet dent. 1963;13:204–227. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(63)90165-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarb GA, Bolender CL, Hickey JC, Carlsson GE. Textbook on bouchers prosthodontic treatment for the elderly. 10. New Delhi: BI Publications Pvt Ltd; 1998. Selecting artificial teeth for the edentulous patient; pp. 330–351. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman W, Jr, Bomberg TJ, Hatch RA. Interalar width as guide in denture tooth selection. J Prosthet Dent. 1986;55:219–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(86)90348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes VL, et al. Interalar distance to estimate the combined width of the six maxillary anterior teeth in oral rehabilitation treatment. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21:26–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wehner PJ, Hickey JC, Boucher CO. Selection of artificial teeth. J prosthet dent. 1967;18:222–232. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(67)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kern BE. Anthropometric parameters of tooth selection. J Prosthet Dent. 1967;17(5):431–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(67)90140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mavroskoufis F, Ritchie GM. The face form as a guide for the selection of maxillary central incisor. J Prosthet Dent. 1980;43(5):501–505. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(80)90319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuoka N, Muramatsu A, Aaiji Y, et al. Discriminative thresholds of cephalometric indexes in the subjective evaluation of facial asymmetry. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdullah MA. Inner canthal distance and geometric progression as a predictor of maxillary central incisor width. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;88:16–20. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.126095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faure JC, Rieffe C, Maltha JC. The influence of different facial components on facial esthetics. Eur J Orthod. 2007;131:609–613. doi: 10.1093/ejo/24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis NC. Smile design. Dent Clin North Am. 2007;51:299–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JH. Dental esthetics. The pleasing appearance of artificial dentures. Bristol: John Wright and Sons, Ltd; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Billmeyer FW, Saltzman M. Principles of color technology. New York: John Wiley &sons Inc; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lombardi RE. The principles of visual perception and their clinical application to denture esthetics. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;23:358–382. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(73)80013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hegenbarth EA. Creative ceramic color: a practical system. Chicago: Quintessence publishing Co, Inc; 1989. pp. 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saleski CG. Color, light and shade matching. J Prosthet Dent. 1972;27:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(72)90033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sellen PN, Phil B, Jagger DC, Harrison A. Methods used to select artificial anterior teeth for the edentulous patient: a historical overview. Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mc Cord JF, Grant AA. Registration: stage III- selection of teeth . Br Dent J. 2000;188:660–661. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krajicek DD. Natural appearance for the individual denture patient. J Prosthet Dent. 1960;10:205. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(60)90041-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furnas IL. Esthetics in full denture construction. J Am Dent Assoc. 1936;23:3. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ricketts RM. The biologic significance of the divine proportion and the Fibonacci series. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:351–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marquardt SR, Stephen R. Marquardt on the golden Decagon and human facial beauty. Interview by Dr. Gottlieb. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36:339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levin EI. Dental esthetics and golden proportion. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;40:244–252. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(78)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qualtrough AJ, Burke FJ. A look at dental esthetics. Quintessence Int. 1994;25:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosentiel SF, Ward DH, Rashid RG. Dentists’ preferences of anterior tooth proportion–a web based study. J Prosthodont. 2000;9:123–136. doi: 10.1053/jopr.2000.19987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward DH. Proportional smile design using the recurring esthetic dental (red) proportion. Dent Clin North Am. 2001;45:143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]