Abstract

We assessed the contribution of angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] to captopril-induced cardiovascular protection in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) chronically treated with the nitric oxide synthesis inhibitor L-NAME (SHR-L). L-NAME (80 mg/L) administration for three weeks increased mean arterial pressure (MAP) from 196 ± 6 mmHg to 229 ± 3 mmHg (p<0.05). Treatment of SHR-L with Ang-(1-7) antagonist, [D-Ala7]-Angiotensin-(1-7) (A779; 744 μg/kg/day ip) further elevated MAP to 253 ± 6 mmHg (p<0.05 vs. SHR-L or SHR). Moreover, A779 treatment attenuated the reduction in MAP and proteinuria by either captopril (300 mg/L in drinking water) or hydralazine (1.5 mg/kg/day ip). In isolated perfused hearts, the recovery of left ventricular function from global ischemia was enhanced by captopril or hydralazine treatment, and was exacerbated with A779. The Ang-(1-7) antagonist attenuated the beneficial effects of captopril and hydralazine on cardiac function. Recovery from global ischemia was also improved in isolated SHR-L hearts acutely perfused with captopril during both the perfusion and reperfusion periods. The acute administration of A779 reduced the beneficial actions of captopril to improve recovery following ischemia. We conclude that during periods of reduced nitric oxide availability, endogenous Ang-(1-7) plays a protective role to effectively buffer the increase in blood pressure and renal injury, as well as the recovery from cardiac ischemia. Moreover, Ang-(1-7) contributes to the blood pressure lowering and tissue protective actions of captopril and hydralazine in a model of severe hypertension and end-organ damage.

Keywords: nitric oxide, heart, A-779, ischemia, hydralazine

INTRODUCTION

Angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] is an alternative peptide product of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) that exhibits blood pressure lowering actions, as well as beneficial effects on end organ damage (1–3) Ang-(1-7) is formed from either Ang I by endopeptidases (neprilysin and prolyl oligopeptidase) or Ang II by carboxypeptidases such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (4–8). The effects of Ang-(1-7) are mediated through the G protein-coupled receptor Mas and involve activation of vasodilatory prostaglandins and nitric oxide (NO) (9–11). Acute immunoneutralization of endogenous Ang-(1-7) reverses the antihypertensive effects of short-term Ang II blockade (12). Moreover, acute Ang-(1-7) receptor blockade stimulates a vasoconstrictor response in dietary salt-restricted SHR and [mRen-2]27transgenic hypertensive rats (13;14). As chronic ACE inhibition or angiotensin II type-1 (AT1) blockade increase the circulating levels of Ang-(1-7), at least part of the therapeutic effects may be mediated through endogenous Ang-(1-7) (15). Blockade of AT(1-7) receptors acutely reversed as much as 32% of the blood pressure-lowering effect of losartan (16). Moreover, increased levels of Ang-(1-7) following ACE inhibition contributes to the improvement in the baroreceptor reflex (17). Chronic AT1 receptor blockade increases expression of ACE2 and Ang-(1-7), as well as the pressure-independent prevention of vascular remodeling in SHR (18). Conversely, ACE2-deficient mice exhibit cardiac dysfunction while Ang-(1-7) improves the recovery after cardiac failure (19;20). Ang-(1-7) treatment mimics the beneficial effects of captopril to attenuate the development of vascular, renal and cardiac dysfunction in L-NAME-treated spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR-LNAME), as well as in hypertensive and normotensive animals type I induced diabetes (21–23). The present study determined whether endogenous Ang-(1-7) contributes to the beneficial effects of long-term ACE inhibition with captopril in the nitric oxide (NO) deficient SHR-LNAME utilizing the Ang-(1-7) antagonist D-Ala7-[Ang-1-7] (D-Ala or A779). To account for the blood pressure-lowering effects of captopril, we also assessed the influence of A779 on the effects of the vasodilator hydralazine.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Chronic studies

Treatment protocol

17-week old male SHR were used in this study in 6 treatment groups: Group 1 was SHR that had L-NAME in their drinking water (80 mg/L for 3 weeks; SHR-LNAME); Group 2 was SHR-LNAME that received captopril in drinking water (300 mg/L) for 3 weeks; Group 3 was SHR-LNAME treated rats that received daily intraperitoneal (ip) injections of hydralazine (1.5 mg/kg/day ip) for 3 weeks. Group 4 was SHR-LNAME treated rats that received daily injections of Ang-(1-7) antagonist [D-Ala7]-Angiotensin-(1-7) (A779), (744 μg/kg/day ip); Groups 5 and 6 were SHR-LNAME that received daily A779 treatment (744 μg/kg/day ip) with either captopril or hydralazine, respectively. The analyses of the various treatment groups were performed in a blinded manner by the investigators. The present studies are in accordance to the NIH guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, 1985) and sanctioned by Kuwait University Research.

Urine/plasma and tissue analysis

At the end of the 4-week treatment period, animals were placed in metabolic cages and food and water were provided ad libitum. The urine collection was carried out for 24 hours, with the sample collection tube immersed in ice-cold water. Total protein was determined as reported (23). At the end of the collection period, the animals were sacrificed by decapitation and trunk blood was collected along. The kidneys and brains were removed, the dorsal medulla separated and frozen on dry ice. The plasma, whole kidney and dorsal medullar were extracted for angiotensin peptides and assayed by three separate RIAs for angiotensin peptides by the Hypertension Core Assay Laboratory of Wake Forest UniversitySchool of Medicine as described (24).

For cytokines, kidneys were homogenized in phosphate buffered saline containing 1% Triton-X-100, kept on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to remove debris. The levels of the IL-6, IL-10 and TGF-β were directly assessed in lysate supernatants by ELISA (Coulter-Immunotech SA, Paris France).

Blood samples were also taken from a group of SHR-LNAME that received daily Ang-(1-7) treatments (576 μg/kg/day) as a comparison with previous studies for the peptides measurements (22).

Blood pressure measurement

Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and the left femoral artery was exposed surgically at the end of the 4 week period. A catheter was inserted and connected to a pressure transducer for blood pressure measurement expressed as mm Hg.

Heart perfusion studies-chronically treated hearts

Rats were anesthetized with Intraval Sodium (40 mg/kg body weight), hearts were rapidly removed after intravenous heparinization (1000 U/kg body weight) and mounted on a ML870B2 Langendorff System (ADI Instruments, USA) perfused initially with a constant pressure perfusion of 50 mm Hg with oxygenated (95% O2 + 5% CO2) KH buffer (37°C). A water-filled balloon was placed into the left ventricle connected to a Statham pressure transducer (P23Db) and volume adjusted to a baseline end-diastolic pressure of 5 mm Hg. Both the left ventricular developed pressure (Pmax) and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) were assessed continuously. Coronary flow (CF) was assessed by an electromagnetic flow probe set in the inflow tubing above the aortic perfusion cannula. The perfusion pressure was obtained from a flow probe in a branch of the aortic cannula by a Statham pressure transducer. Pressure was maintained at a 50 mm Hg by a perfusion pressure control module. This system permits accurate adjustment of perfusion pressure between 5–300 mmHg to an accuracy of ± 1 mm Hg. Hearts were perfused (30 minutes) following by 40 minutes of ischemia (I) and subsequently a 30 minute period of reperfusion (R). Left ventricular contractility and hemodynamics following I/R period were established as previously described (22).

Acute heart perfusion with captopril and Ang-(1-7)

A separate group of SHR-LNAME was used for the acute studies. Hearts from SHR-LNAME were removed and mounted on the Langendorff perfusion system as described above. Seven groups were studied: Group 1A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer for 30 minutes (perfusion) and then subjected to 40 minutes of ischemia (I) followed by a period of 30 minutes reperfusion (Re); Group 2A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer containing Ang-(1-7) (0.22 pM) during perfusion before I/R; Group 3A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer containing Ang-(1-7) during reperfusion after ischemia; Group 4A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer containing captopril (30 μM) during perfusion before ischemia; Group 5A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer containing captopril + A779 (115 nM) during perfusion before ischemia; Group 6A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer containing captopril during reperfusion after ischemia; Group 7A was hearts that were perfused with KH buffer containing captopril + A779 during reperfusion after ischemia.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM of ‘n’ number of experiments. MAP, plasma and tissue angiotensin peptides, serum hormones, urine volume and protein results were analyzed and figures constructed using Graph pad Prism software version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The mean values were compared using an analysis of variance with subsequent Bonferroni’s post hoc test. For unequal variances in the tissue and plasma peptide values, log transformations were used prior to analysis. The difference was considered to be significant p ≤ 0.05. Heart reperfusion values were compared with their respective baseline controls using a two tailed, paired t-test. The comparison between different experimental groups was performed with a general factorial analysis of variance. The software program SPSS for Windows (V.6.0.1; SPSS Inc. Evanston, Illinois, USA) was utilized for statistical analysis. Additional comparisons were achieved using univariate Scheffes’ confidence intervals for the parametric estimates.

Drugs

L-NAME, A779, captopril, and hydralazine, were obtained from Sigma Biochemical (USA).

RESULTS

Mean arterial pressure (MAP)

As shown in Table 1, oral administration of L-NAME orally (80 mg/L) for three weeks markedly elevated mean arterial pressure (MAP). Treatment with either captopril or hydralazine significantly attenuated the elevation in MAP due to L-NAME. The administration of the Ang-(1-7) receptor antagonist A779 further increased MAP. The combination of captopril and A779 reversed the effects of captopril in reducing MAP. The beneficial effect of hydralazine on MAP was also inhibited in part by the co-administration of A779.

Table 1.

Effect on MAP and Proteinuria

| Groups studied | MAP (mmHg) | Animal Body Weight (g) | Urine Volume (mL/24hrs) | Urine Protein (mg/24hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SHR-LNAME | 229 ± 2 | 348 ± 18 | 31 ± 13 | 148 ± 2 |

| 2. +Captopril | 197 ± 5* | 329 ± 17 | 28 ± 4 | 89 ± 5* |

| 3. +Hydralazine | 172 ± 5* | 333 ± 8 | 22 ± 7 | 83 ± 4* |

| 4. +A779 | 253 ± 6* | 243 ± 19* | 24 ± 5 | 157 ± 2 |

| 5. +Captopril/A779 | 223 ± 4# | 346 ± 15 | 39 ± 8 | 139 ± 44 |

| 6. +Hydralazine/A779 | 224 ± 2§ | 317 ± 11 | 20 ± 4 | 178 ± 23§ |

Data presented as Mean ± SEM (N = 6 – 8),

Value significantly different from SHR-LNAME p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Hydralazine, p < 0.05.

Urine volume and proteinuria

Urine volume and urinary protein were measured in all the groups studied (Table 1). There were no differences in urine volume among groups. Chronic treatment of the SHR-LNAME animals with captopril or hydralazine resulted in a similar reduction in urinary protein (Table 1). Although A779 alone did not influence proteinuria in the SHR-LNAME, the beneficial effects of both captopril and hydralazine to reduce proteinuria were significantly attenuated in the groups that were co-administered the Ang-(1-7) antagonist (Table 1).

Plasma, kidney and brain tissue angiotensins

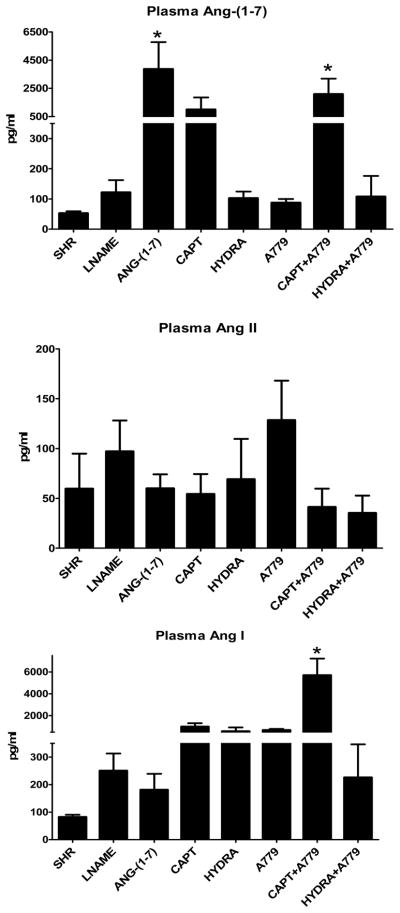

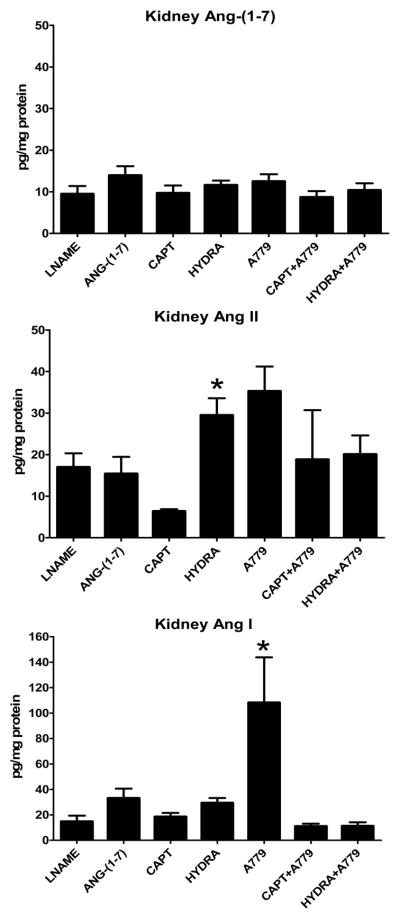

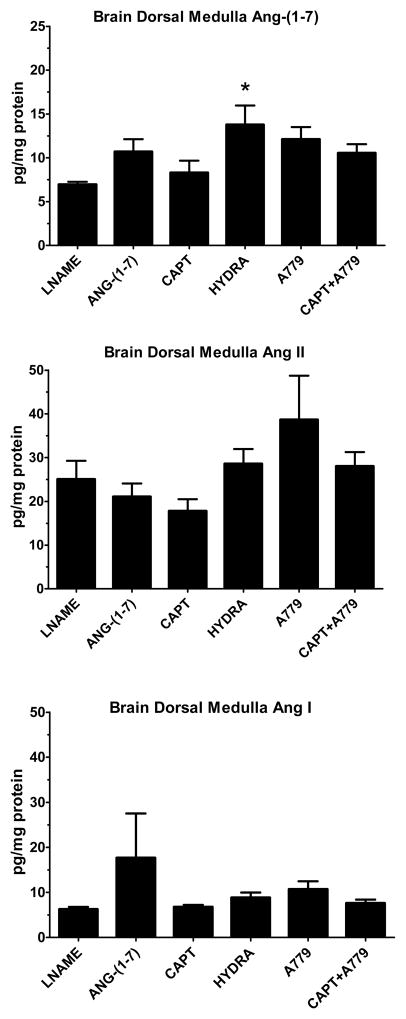

Chronic Ang-(1-7) treatment increased plasma Ang-(1-7) levels ~25 fold in comparison to the SHR-LNAME (Figure 1). A similar elevation of plasma Ang-(1-7) to exogenous administration of the peptide occurred for both the captopril and the captopril/A779 groups, although the only the latter group reached significance versus the SHR-LNAME. No significant differences in plasma Ang-(1-7) were detected following hydralazine or A779 treatment either alone or in combination. There were no significant differences in plasma Ang II following Ang-(1-7) or in the other treated SHR-LNAME groups (Figure 1). Plasma Ang I was significantly elevated only in the captopril/A779 group as compared to SHR-LNAME (Figure 1). In contrast to the circulation, there were no changes in kidney tissue Ang-(1-7) among any of the treatment groups (Figure 2). Renal levels of Ang II tended to decline with captopril treatment, but were significantly higher following the hydralazine regimen as compared to the SHR-LNAME rats (Figure 2). Renal Ang I was elevated only in the A779-treated group relative to the SHR-LNAME controls (Figure 2). All three angiotensin peptides were detected in tissue extracts from the brain dorsal medulla (Figure 3). Medullary tissue levels of Ang-(1-7) were higher in the hydralazine-treated groups as compared to SHR-LNAME controls. There were no significant changes in the medullary content of either Ang II or Ang I among any of the groups in comparison to SHR-LNAME (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Plasma angiotensin concentrations in SHR, SHR-LNAME, SHR-LNAME infused with Ang-(1-7), SHR-LNAME and captopril (CAPT), SHR-LNAME and hydralazine (HYDRA), SHR-LNAME and A779, captopril and A779 (CAPT + A779), hydralazine and A779 (HYDRA + A779). (Mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group). *P<0.05 versus SHR-LNAME.

Figure 2.

Kidney tissue concentrations of angiotensins in SHR-LNAME, SHR-LNAME infused with Ang-(1-7), SHR-LNAME and captopril (CAPT), SHR-LNAME and hydralazine (HYDRA), SHR-LNAME and A779, captopril and A779 (CAPT + A779), hydralazine and A779 (HYDRA + A779). (Mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group). *P<0.05 versus SHR-LNAME.

Figure 3.

Brain dorsal medullary concentrations of angiotensins in SHR-LNAME, SHR-LNAME infused with Ang-(1-7), SHR-LNAME and captopril (CAPT), SHR-LNAME and hydralazine (HYDRA), SHR-LNAME and A779, captopril and A779 (CAPT + A779). (Mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group). *P<0.05 versus SHR-LNAME.

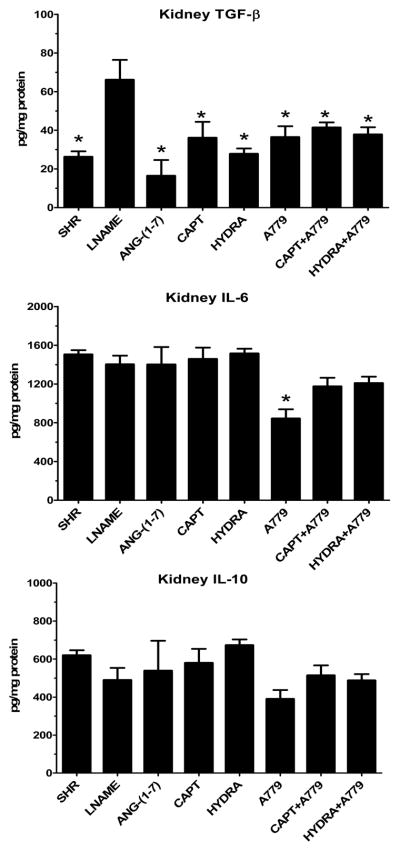

Kidney tissue cytokines

Tissue cytokines TGF-β, IL-6 and IL-10 were assessed in the kidneys from the control SHR, SHR-LNAME and other treated groups. As shown in Figure 4, the renal content of TGF-β was significantly higher following LNAME administration as compared to the SHR control or those treated with Ang-(1-7), captopril and hydralazine. TGF-β levels were also lower in the A779 and hydralazine/A779 groups as compared to SHR-LNAME alone (Figure 4). Renal levels of IL-6 were similar among the various groups except for the A779-treated rats which exhibited significantly lower levels of IL-6 compared to SHR-LNAME (Figure 4). Finally, the renal tissue levels of IL-10 were similar among all groups except for the A779 group that exhibited expression compared to the hydralazine treated rats (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kidney tissue of the cytokines TGF-β, IL-6 and IL10 in SHR, SHR-LNAME, SHR-LNAME infused with Ang-(1-7), SHR-LNAME and captopril (CAPT), SHR-LNAME and hydralazine (HYDRA), SHR-LNAME and A779, captopril and A779 (CAPT + A779), hydralazine and A779 (HYDRA + A779). (Mean ± SEM, n = 4–8 per group). *P<0.05 versus SHR-LNAME.

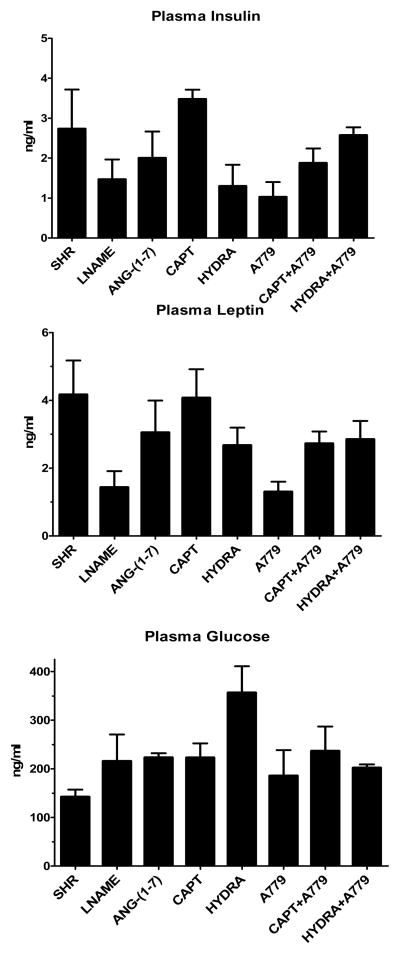

Metabolic hormone profile

Insulin, leptin and glucose levels were measured in plasma samples collected at the end of the study. There were no individual differences within each group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Plasma concentrations of insulin, leptin and glucose in SHR, SHR-LNAME, SHR-LNAME infused with Ang-(1-7), SHR-LNAME and captopril (CAPT), SHR-LNAME and hydralazine (HYDRA), SHR-LNAME and A779, captopril and A779 (CAPT + A779), hydralazine and A779 (HYDRA + A779). (Mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group). *P<0.05 versus SHR-LNAME.

Cardiac recovery from ischemia/reperfusion

Tables 2 and 3 provide the values for Pmax, LVEDP and coronary flow for the chronic treatment among the six groups of SHR. A779 alone did not alter the recovery in cardiac function as compared with SHR-LNAME. The combined administration of either captopril or hydralazine with A779 to SHR-LNAME significantly inhibited the recovery in Pmax (Table 2) and coronary flow (Table 3) compared to captopril or hydralazine treatments alone. For LVEDP, the improvement with hydralazine was attenuated by the A779 treatment; however, there was continued improvement in the LVEDP in hearts treated with the combination of captopril plus A779.

Table 2.

Effect on post ischemic recovery in global contractility

| Groups studied | Pmax (mmHg) | LVEDP (mmHg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Reperfusion | % R | Control | Reperfusion | % R | |

| 1. SHR-LNAME | 58 ± 24 | NR | NR | 12 ± 1 | 64 ± 1 | 542 ± 27 |

| 2. +Captopril | 60 ± 6 | 35 ± 2 | 58 ± 4* | 10 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 418 ± 47* |

| 3. +Hydralazine | 64 ± 8 | 30 ± 4 | 47 ± 4* | 12 ± 3 | 33 ± 2 | 304 ± 53* |

| 4. +A779 | 54 ± 7 | NR | NR | 11 ± 1 | 60 ± 4 | 532 ± 36 |

| 5. +Captopril/A779 | 36 ± 9 | 7 ± 2 | 19 ± 4*# | 12 ± 1 | 45 ± 3 | 369 ± 21*# |

| 6. +Hydralazine/A779 | 57 ± 2 | NR | NR§ | 12 ± 1 | 59 ± 5 | 493 ± 56§ |

The data were computed at 30 minute reperfusion, and expressed as mean ± SEM (N = 6 – 8).

Pmax=Left ventricular developed pressure; LVEDP = Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; % R = % Recovery (reperfusion/control); NR = No Recovery after ischemia.

Value significantly different from SHR-LNAME, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Hydralazine, p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Effect on post ischemic recovery in coronary flow

| Groups studied | Coronary Flow (ml.min−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Reperfusion | % R | |

| 1. SHR-LNAME | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 10 ± 1 |

| 2. +Captopril | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 63 ± 2* |

| 3. +Hydralazine | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 45 ± 2* |

| 4 +A779 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 14 ± 3 |

| 5. +Captopril/A779 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 14 ± 2# |

| 6. +Hydralazine/A779 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 18 ± 2*§ |

The data were computed at 30 minute reperfusion, and expressed as mean ± SEM (N = 6 – 8).

% R= % Recovery (reperfusion/control); NR=No Recovery after ischemia.

Value significantly different from SHR-LNAME, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Hydralazine, p < 0.05.

Tables 4 and 5 provide the actual values for Pmax, LVEDP and coronary flow from the acute treatment study in the SHR-LNAME groups. The acute administration of Ang-(1-7) in either the perfusion or reperfusion (Re) buffers improved recovery of Pmax, LVEDP (Table 4) and coronary flow (Table 5). Similarly, captopril improved cardiac function in either the perfusion or reperfusion (Re) periods. The co-administration of A779 reversed the effects of captopril on Pmax and LVEDP (Table 4), as well as coronary flow. The administration of A779 alone exacerbated recovery for both Pmax and LVEDP (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect on post ischemic recovery in global contractility-acute study

| Groups studied | Pmax (mmHg) | LVEDP (mmHg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Reperfusion | % R | Control | Reperfusion | % R | |

| 1A. SHR-LNAME | 217 ± 18 | 11 ± 6 | 6 ± 3 | 13 ± 1 | 116 ± 8 | 916 ± 81 |

| 2A. +Ang-(1-7) | 199 ± 13 | 82 ± 9 | 42 ± 6* | 13 ± 1 | 74 ± 9 | 587 ± 29* |

| 3A. +Ang-(1-7) Re | 215± 14 | 111 ± 9 | 52 ± 4* | 13± 2 | 61 ± 7 | 469 ± 75* |

| 4A. +Captopril | 133 ± 14 | 73 ± 11 | 56 ± 9* | 13 ± 1 | 84 ± 4 | 643 ± 37* |

| 5A. +Captopril/A779 | 164 ± 20 | 10 ± 1 | 6 ± 1# | 11± 1 | 103 ± 4 | 936 ± 80# |

| 6A. +Captopril Re | 188 ± 32 | 71 ± 16 | 37± 3* | 13 ± 1 | 65 ± 4 | 515 ± 53* |

| 7A. +Captopril/A779 Re | 226 ± 27 | 8 ± 6 | 3 ± 2§ | 13 ± 2 | 127 ± 16 | 980 ± 53§ |

| 8A. +A779 | 174 ± 14 | NR | NR | 11 ± 1 | 126 ± 12 | 1148± 63* |

| 9A +A779 Re | 184 ± 22 | NR | NR | 13 ± 2 | 136 ± 22 | 1054± 75* |

The data were computed at 30 minute reperfusion, and expressed as mean ± SEM (N = 6 – 8).

Pmax = Left ventricular developed pressure; LVEDP = Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; Re = Reperfusion; % R = % Recovery (reperfusion/control)

Value significantly different from SHR-LNAME, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril Perfusion, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril Reperfusion (RE), p < 0.05.

Table 5.

Effect on post ischemic recovery in coronary flow-acute study

| Groups studied | Coronary Flow (ml.min−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Reperfusion | % R | |

| 1A. SHR-LNAME | 13 ± 1.6 | 2± 0.5 | 15 ± 4 |

| 2A. +Ang-(1-7) | 7 ± 0.2 | 3 ± 0.3 | 40± 3* |

| 3A. +Ang-(1-7) Re | 9 ± 1.6 | 5± 0.8 | 48 ± 2* |

| 4A. +Captopril | 8 ± 0.5 | 3 ± 0.2 | 44 ± 1* |

| 5A. +Captopril/A779 | 7 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.4 | 11 ± 4# |

| 6A. +Captopril Re | 8± 0.7 | 4 ± 0.8 | 52 ± 9* |

| 7A. +Captopril/A779 Re | 9 ± 0.6 | 2 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 1*§ |

| 8A. +A779 | 11 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.3 | 10 ± 3 |

| 9A. +A779 Re | 9 ± 22 | 1 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 2 |

The data were computed at 30 minute reperfusion, and expressed as mean ± SEM (N = 6 – 8).

% R= % Recovery (reperfusion/control); Re = reperfusion

Value significantly different from SHR-LNAME, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril Perfusion, p < 0.05.

Value significantly different from Captopril Reperfusion (Re), p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In SHR that exhibit endothelial dysfunction produced by chronic inhibition of NO with LNAME, Ang-(1-7) receptor blockade attenuates the beneficial effects of captopril or hydralazine treatment on blood pressure, cardiac and renal damage. Our previous studies in the SHR-LNAME rat revealed that chronic treatment with Ang-(1-7) produced a significant decrease in blood pressure comparable to that of an ACE inhibitor, improved recovery of cardiac function following global ischemia, and lessened the extent of proteinuria associated with the severe hypertension in this model of NO deficiency (22). These observations are consistent with the present findings that plasma Ang-(1-7) following captopril treatment approach the plasma content obtained with daily treatment of exogenous Ang-(1-7). Surprisingly, the Ang-(1-7) antagonist A779 also reversed part of the beneficial actions of hydralazine despite the lack of an increase in plasma Ang-(1-7) following hydralazine treatment. Neither captopril nor hydralazine altered the kidney tissue concentrations of Ang-(1-7); however, hydralazine treatment was associated with a significant increase in dorsal medullary levels of Ang-(1-7). Finally, renal tissue levels of TGF-β were increased following LNAME and were reduced by Ang-(1-7) treatment, as well as captopril and hydralazine.

Plasma levels of Ang-(1-7) increased 5-fold with captopril and 25-fold with daily administration of exogenous Ang-(1-7) in the SHR-LNAME group. The plasma levels of Ang-(1-7) attained in this study are higher than those reported by Strawn and colleagues where the peptide was given intravenously via osmotic minipump (25). Van der Wouden reported that a similar dose of Ang-(1-7) increased plasma Ang-(1-7) 14 to 40-fold in the adriamycin model of renal injury with exaggerated proteinuria (26). It is possible that the significant reduction in glomerular filtration in both the SHR-LNAME and adriamycin-treated rats would reduce clearance of the peptide thereby contributing to higher circulating levels. In the study by Van der Wouden study, A779 treatment did not attenuate the effects of an ACE inhibitor to improve proteinuria and exogenous Ang-(1-7) had no effect on its own (26). Moreover, ACE inhibition offered a comparable benefit to an AT1 receptor antagonist suggesting that Ang-(1-7) does not influence renal injury in this model (26). The previous study also reported that ACE inhibition effectively lowered plasma Ang II levels. In contrast, the present data reveal no differences in plasma Ang II among groups, suggesting that the protective effects of the treatments in our study may not necessarily reflect changes in circulating Ang II.

Chronic treatment with NOS inhibitor L-NAME significantly increased proteinuria and exacerbated the hypertension. In previous studies, captopril treatment was more effective than Ang-(1-7) in protecting the SHR-LNAME kidneys as proteinuria following captopril was reduced to that of the control SHR (22). Since the combination of Ang-(1-7) with captopril did not have additive effects on proteinuria, we suggested that both decreased Ang II and increased Ang-(1-7) may play a role in this effect (22). In the present study, both captopril and hydralazine produced comparable reductions in urinary protein and MAP that were completely reversed by the Ang-(1-7) receptor antagonist. These findings argue that reductions in Ang II may not be involved in the reversal of the renal injury associated with these two agents. Moreover, the attenuated proteinuria cannot be dissociated from lessening of renal injury due to lower MAP in the treated animals since co-administration of A779 blocked the reduction in MAP by either captopril or hydralazine. In further support of a role for Ang-(1-7), we find no significant effect of captopril or hydralazine on plasma and kidney levels of Ang II. Although there was no effect on renal Ang-(1-7) levels, the large increases in circulating Ang-(1-7) occurring with either captopril or exogenous Ang-(1-7) suggest that perhaps maximal effects are achieved in both situations. However, we did not determine whether higher doses of the ACE inhibitor would cause a further reduction in blood pressure and proteinuria, and the extent that the Ang-(1-7) antagonist would reverse these effects. The present data suggest that increased circulating Ang-(1-7) is likely responsible for the beneficial effects of captopril within the heart and kidney directly. Indeed, Wang and colleagues demonstrate that circulating rather than tissue levels of Ang-(1-7) were more beneficial to the heart following induced myocardial infarction (27). Finally, we note that treatment with Ang-(1-7), captopril or hydralazine reduced the pro-fibrotic cytokine TGF-β within the kidney of the SHR-LNAME rats. These data support several studies in various tissues including the heart, lung, aorta and breast tumor cells that the anti-fibrotic actions of Ang-(1-7) area associated with a reduction in TGF-β expression (28–32).

In contrast to the ACE inhibitor, hydralazine did not elevate Ang-(1-7) content in the plasma or kidney. Ang-(1-7) is known to stimulate NO which may contribute to the anti-hypertensive and vasodilatory effects of the peptide (33–36). The mechanism of action for hydralazine may also involve NO through the upregulation of cGMP, as well as antioxidant actions (37–40). Although evidence for the direct release of NO in response to hydralazine is lacking, a delayed increase in cGMP does occur (41). The report that hydralazine may sensitize or at least maintain NO sensitivity in vascular tissue via inhibition of an NAD(P)H oxidase provides a potential mechanism for an indirect enhancement of the actions of NO (37). Therefore, hydralazine may potentiate the NO-dependent responses evoked by Ang-(1-7). Thus, different mechanisms appear to participate in the protection mediated by hydralazine versus captopril.

The recovery of left ventricular function following global ischemia was improved in animals treated long-term with Ang-(1-7) or captopril in SHR-LNAME as previously reported (22). In the present study, both hydralazine and captopril increased the recovery from ischemia in terms of Pmax, LVEDP and coronary flow; these indices were partially reversed by Ang-(1-7) blockade. We previously reported that the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin reversed the improvement in recovery due to Ang-(1-7) which is consistent with the actions of the peptide to stimulate prostaglandins (22). However, we do not know the mechanisms underlying the effects of hydralazine versus captopril in the present study. It was interesting to note that the Ang-(1-7) antagonist A779 reduced LVEDP further in the captopril-treated group. Perhaps the high levels of Ang-(1-7) in this group have a biphasic action on cardiac function. In this regard, De Mello et al. (42) reported that Ang-(1-7) exhibits biphasic effects on arrithymias in a model of cardiac failure. The effects of acute treatment with Ang-(1-7) or captopril were also studied after global cardiac ischemia. Ang-(1-7) in either the perfusion or reperfusion buffer improved the Pmax, LVEDP and coronary flow. Similar effects were obtained in the presence of captopril with either the perfusion or reperfusion buffers, and these beneficial effects were reversed with A779 co-treatment. The present data suggests that the actions of Ang-(1-7) at least in terms of cardiac function appear to contribute to both acute and chronic effects of captopril.

In conclusion, the condition of impaired NO synthesis accompanied by severe hypertension and end-organ damage, chronic administration of Ang-(1-7) clearly provides a protective effect on vascular, heart and kidney function. Many of the effects of Ang-(1-7) mimic chronic treatment with captopril and the effects of both treatments have been shown to involve both NO- and prostaglandin-dependent mechanisms. The present findings further confirm these overlapping mechanisms by illustrating that an increase in circulating Ang-(1-7) occurs in response to 4 week captopril treatment and that Ang-(1-7) receptor blockade over this time period reverses the protective actions of the ACE inhibitor. The mechanisms of hydralazine action on the vasculature and for lowering MAP are not fully elucidated and will require further study. On the basis of the present data, we conclude that Ang-(1-7) contributes to many of the beneficial effects of this vasodilator; however, this is not a result of elevated circulating or renal tissue levels of the peptide. Interactions through NO availability or upregulation of the Ang-(1-7)/Mas receptor by hydralazine remain possible explanations for further exploration. Taken together with previous reports, the present data provide compelling evidence for a major contribution of Ang-(1-7) to the blood pressure lowering and end-organ protection provided by ACE inhibition and hydralazine treatment in a severe form of hypertensive resulting from NO deficiency.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Kuwait University Research Administration (RM 02/03) and NIH grants HL-51952 and HL-56973.

Literature Cited

- 1.Chappell MC. Emerging evidence for a functional angiotesin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin-(1-7) mas receptor axis; more than regulation of blood pressure? Hypertension. 2007;50(4):596–599. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.076216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1-7): an evolving story in cardiovascular regulation. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):515–521. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196268.08909.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Simoes e Silva AC. Recent advances in the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin(1-7)-Mas axis. Exp Physiol. 2008;93(5):519–527. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaltout HA, Westwood B, Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Figueroa J, Diz DI, Rose JC, Chappell MC. Angiotensin metabolism in renal proximal tubules, urine and serum of sheep: Evidence for ACE2-dependent processing of Angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;292:F82–F91. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00139.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allred AJ, Diz DI, Ferrario CM, Chappell MC. Pathways for angiotensin-(1-7) metabolism in pulmonary and renal tissues. Am J Physiol. 2000;279(5):F841–F850. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto K, Chappell MC, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. In vivo metabolism of angiotensin I by neutral endopeptidase (EC 3.4.24.11) in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1992;19:692–696. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos RAS, Brosnihan KB, Jacobsen DW, DiCorleto PE, Ferrario CM. Production of angiotensin-(1-7) by human vascular endothelium. Hypertension (Suppl II) 1992;19:56–61. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.2_suppl.ii56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garabelli PJ, Modrall JG, Penninger JM, Ferrario CM, Chappell MC. Distinct roles for angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and carboxypeptidase A in the processing of angiotensins in the murine heart. Exp Physiol. 2008;93(5):613–621. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de BI, Heringer-Walther S, Pinheiro SV, Lopes MT, Bader M, Mendes EP, Lemos VS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Schultheiss HP, Speth R, Walther T. Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(14):8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampaio WO, Henrique de CC, Santos RA, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1-7) counterregulates angiotensin II signaling in human endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2007;50(6):1093–1098. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gwathmey TM, Westwood BM, Pirro NT, Tang L, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. The Nuclear Angiotensin-(1-7) Receptor is Functionally Coupled to the Formation of Nitric Oxide. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299(5):F983–890. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00371.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer SN, Chappell MC, Yamada K, Ferrario CM. Endogenous inhibition of angiotensin-(1-7) reverses the antihypertensive effects of blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 1997;309(3):477–483. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyer SN, Averill DB, Chappell MC, Yamada K, Jones AG, Ferrario CM. Contribution of angiotensin-(1-7) to blood pressure regulation in salt-depleted hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2000;36:417–422. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iyer SN, Yamada K, Diz DI, Ferrario CM, Chappell MC. Evidence that prostaglandins mediate the antihypertensive actions of angiotensin-(1-7) during chronic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:109–117. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200007000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrario CM, Jessup JA, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Smith RD, Chappell MC. Effects of renin angiotensin system blockade on renal angiotensin-(1-7) forming enzymes and receptors. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2189–2196. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyer SN, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Diz DI, Ferrario CM. Vasodepressor actions of angiotensin-(1-7) unmasked during combined treatment with lisinopril and losartan. Hypertension. 1998;31:699–705. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.2.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancini GBJ, Henry GC, Macaya C, O’Neill BJ, Pucillo AL, Carere RG, Wargovich TJ, Mudra H, Luscher TF, Klibaner MI, Haber HE, Uprichard ACG, Pepine CJ, Pitt B. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with quinapril improves endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease: the TREND (trial on reversing ENdothelia dysfunction) study. Circulation. 1996;94:258–265. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igase M, Strawn WB, Gallagher PE, Geary RL, Ferrario CM. Vascular AT1 receptors but not arterial pressure regulate ace2 expression in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(3):H1013–H1019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00068.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loot AE, Roks AJM, Henning RH, Tio RA, Suurmeijer AHH, Boomsma F, vanGilst WH. Angiotensin-(1-7) attenuates the development of heart failure after myocardial infarction in rats. Circulation. 2002;105:1548–1550. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013847.07035.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dos-Santo AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, Scholey J, Bray MR, Ferrario CM, Backx PH, Manoukian AS, Chappell MC, Yagil Y, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benter IF, Yousif MHM, Cojocel C, Al-Maghrebi M, Diz DI. Angiotensin-(1-7) prevents diabetes-induced cardiovascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;292:H666–H672. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00372.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benter IF, Yousif MHM, Anim JT, Cojocel C, Diz DI. Angiotensin-(1-7) prevents development of severe hypertension and end-organ damage in spontaneously hypertensive rats treated with L-NAME. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H684–H691. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00632.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benter IF, Yousif MH, Dhaunsi GS, Kaur J, Chappell MC, Diz DI. Angiotensin-(1-7) prevents activation of NADPH oxidase and renal vascular dysfunction in diabetic hypertensive rats. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28(1):25–33. doi: 10.1159/000108758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Westwood BM, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC. Sex differences in circulating and renal angiotensins of hypertensive mRen(2). Lewis but not normotensive Lewis rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H10–H20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01277.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strawn WB, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1-7) reduces smooth muscle growth after vascular injury. Hypertension. 1999;33(Pt. II):207–211. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Wouden EA, Henning RH, Deelman LE, Roks AJ, Boomsma F, de ZD. Does angiotensin (1-7) contribute to the anti-proteinuric effect of ACE-inhibitors? J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2005;6(2):96–101. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2005.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Qian C, Roks AJ, Westermann D, Schumacher SM, Escher F, Schoemaker RG, Reudelhuber TL, van Gilst WH, Schultheiss HP, Tschöpe C, Walther T. Circulating rather than cardiac angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates cardioprotection after myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:286–293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.905968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng W, Chen W, Leng X, He JG, Ma H. Chronic angiotensin-(1-7) administration improves vascular remodeling after angioplasty through the regulation of the TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway in rabbits. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389(1):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Mao H, Katovich MJ. Chronic angiotensin-(1-7) prevents cardiac fibrosis in DOCA-salt model of hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2417–H2423. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01170.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shenoy V, Ferreira AJ, Qi Y, Fraga-Silva RA, Diez-Freire C, Dooies A, Jun JY, Sriramula S, Mariappan N, Pourang D, Venugopal CS, Francis J, Reudelhuber T, Santos RA, Patel JM, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiogenesis-(1-7)/Mas axis confers cardiopulmonary protection against lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1065–1072. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1840OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grobe JL, Der SS, Stewart JM, Meszaros JG, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ. ACE2 overexpression inhibits hypoxia-induced collagen production by cardiac fibroblasts. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113(8):357–364. doi: 10.1042/CS20070160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook KL, Metheny-Barlow LJ, Tallant EA, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1-7) reduces fibrosis in orthotopic breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2010;70(21):8319–8328. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brosnihan KB, Li P, Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-(1-7) dilates canine coronary arteries through kinins and nitric oxide. Hypertension. 1996;27:523–528. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren Y, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Vasodilator action of angiotensin-(1-7) on isolated rabbit afferent arterioles. Hypertension. 2002;39(3):799–802. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.104673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gwathmey TM, Shaltout HA, Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Figueroa JP, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Nuclear angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptors are functionally linked to nitric oxide production. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296(6):F1484–F1493. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90766.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sampaio WO, dos Santos RA, Faria-Silva R, de Mata Machado LT, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1-7) through receptor mas mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via Akt-dependent pathways. Hypertension. 2007;49:185–192. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251865.35728.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munzel T, Kurz S, Rajagopalan S, Thoenes M, Berrington WR, Thompson JA, Freeman BA, Harrison DG. Hydralazine prevents nitroglycerin tolerance by inhibiting activation of a membrane-bound NADH oxidase. A new action for an old drug. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(6):1465–1470. doi: 10.1172/JCI118935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidrio H, Gonzalez-Romo P, Alvarez E, Alcaide C, Orallo F. Hydralazine decreases sodium nitroprusside-induced rat aortic ring relaxation and increased cGMP production by rat aortic myocytes. Life Sci. 2005;77(24):3105–3116. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vidrio H, Fernandez G, Medina M, Alvarez E, Orallo F. Effects of hydrazine derivatives on vascular smooth muscle contractility, blood pressure and cGMP production in rats: comparison with hydralazine. Vascul Pharmacol. 2003;40(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daiber A, Oelze M, Coldewey M, Kaiser K, Huth C, Schildknecht S, Bachschmid M, Nazirisadeh Y, Ullrich V, Mulsch A, Munzel T, Tsilimingas N. Hydralazine is a powerful inhibitor of peroxynitrite formation as a possible explanation for its beneficial effects on prognosis in patients with congestive heart failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338(4):1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei S, Kasuya Y, Yanagisawa M, Kimura S, Masaki T, Goto K. Studies on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by hydralazine in porcine coronary artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;321(3):307–314. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Mello WC, Ferrario CM, Jessup JA. Beneficial versus harmful effects of Angiotensin (1-7) on impulse propagation and cardiac arrhythmias in the failing heart. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2007;8(2):74–80. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2007.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]