Abstract

Transition metal-catalyzed N-atom transfer reactions of azides provide efficient ways to construct new carbon–nitrogen and sulfur–nitrogen bonds. These reactions are inherently green: no additive besides catalyst is needed to form the nitrenoid reactive intermediate, and the by-product of the reaction is environmentally benign N2 gas. As such, azides can be useful precursors for transition metal-catalyzed N-atom transfer to sulfides, olefins and C–H bonds. These methods offer competitive selectivities and comparable substrate scope as alternative processes to generate metal nitrenoids.

Introduction

Azides participate in a wide range of reactions that construct new carbon–nitrogen or nitrogen–heteroatom bonds.1 Their reactivity has motivated considerable research interest since the discovery of phenyl azide in 1864.2 Azides have enjoyed a renaissance in recent years since their potential was recognized for use in “click” reactions, which rapidly increase molecular complexity by bringing together two molecules together in a reliable and stereoselective fashion.3,4 Their use in transition metal-catalyzed N-atom transfer reactions, however, has garnered considerably less attention than other nitrenoid precursors despite the attractiveness of azides.5–7 Their appeal stems from (1) their ready availability from sodium azide;8,9 (2) they require no additive besides catalyst to form the nitrenoid reactive intermediate; and (3) the by-product of the N-atom transfer reaction is N2 gas. These positive attributes provide motivation to develop high yielding and stereoselective N-atom transfer reactions, and this perspective describes the recent progress to achieve these atom-economical and environmentally benign processes.

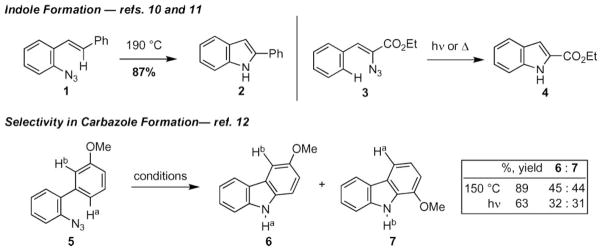

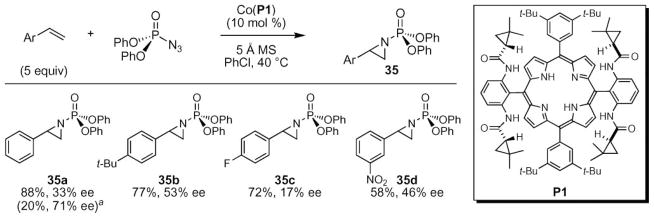

Azides were recognized early as nitrene precursors.1,10,11 Thermolysis or photolysis of biaryl azides was reported by Smith and co-workers in 1951 to afford substituted carbazoles.11d This result was extended to styryl azides (e.g. 1) by Sundberg and co-workers and to vinyl azides (e.g. 3) by Hemetsberger and co-workers. While good to excellent yields can be achieved with aryl- or vinyl substituents, carbazole formation is not generally selective: thermolysis or photolysis of biaryl azide 5 produced a 1 : 1 mixture of the two possible carbazole products (Scheme 1).12

Scheme 1.

Representative examples of intramolecular C–H bond amination to afford indoles or carbazoles.

The reactivity of the aryl azide depends on the identity of the ortho-substituent. When a methylene spacer was placed in between the two π-systems, the temperature controlled the amount of electrophilic cyclization versus C–H bond amination: at 190 °C, azepine 9 was formed; whereas, flash vacuum pyrolysis (350 °C) produced 10 and acridine 11 (Scheme 2).13 Extending the spacer length by an additional methylene eliminates azepine formation to produce indoline 13 or indole 2, albeit with reduced yields.14b,15,16 In contrast to aryl azides, few selective intramolecular cyclizations of nitrenes derived from sulfonyl-,17 acyl-,18 or phosphoryl19 azides exist. Even fewer synthetically useful examples of intermolecular thermal or photochemical N-atom transfer have been reported.18,20–22

Scheme 2.

Examples of intramolecular sp3-C–H bond amination processes.

Thermal- and photochemical reactions of azides demonstrated their potential as precursors for nitrenes. While these reactions do provide access to a variety of N-heterocycles, they are limited by the hyper reactivity of the nitrene, which can lead to poor selectivity and extensive decomposition. Attenuating the reactivity of the nitrene by developing transition metal-catalyzed decomposition reactions of azides to provide nitrenoids would address these limitations. The development of mild, low temperature reactions would enable azides to realize their potential in N-atom transfer reactions.

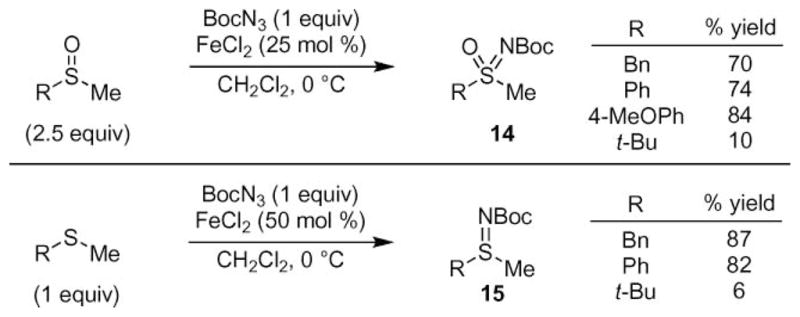

Transition-metal catalyzed N -atom transfer to sulfides

The thermal or photochemical transfer of nitrene from an azide to the sulfur-atom in a sulfide or sulfoxide produces sulfoximides and sulfimides.23 Due to the harsh conditions required to liberate nitrene, however, the yield of these processes is low. These unproductive side reactions and the hazards associated with the thermolysis of azides make this reaction a good target for catalysis. Iron(II) chloride was reported by Bach and co-workers to dramatically improve the synthetic efficiency of this process by reducing the reaction temperature from 90 °C to 0 °C (Scheme 3).24,25 These mild conditions allowed tert-butoxycarbonyl azide (Boc–N3) to be used as the source of the nitrogen-atom. In addition to sulfides and sulfoxides, other nucleophiles could be used in this reaction including silyl enol ethers, although the yield was modest.

Scheme 3.

Examples of intermolecular C–H Bond amination reactions.

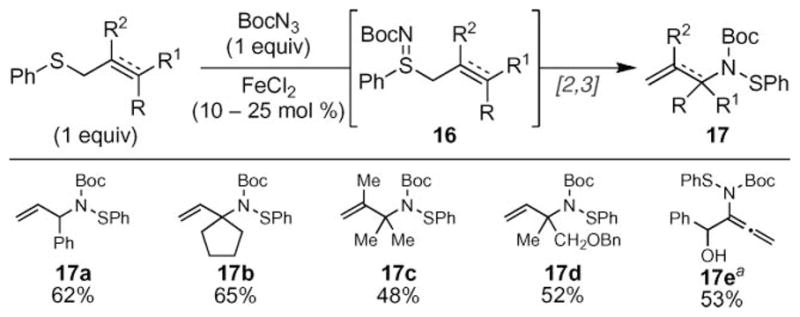

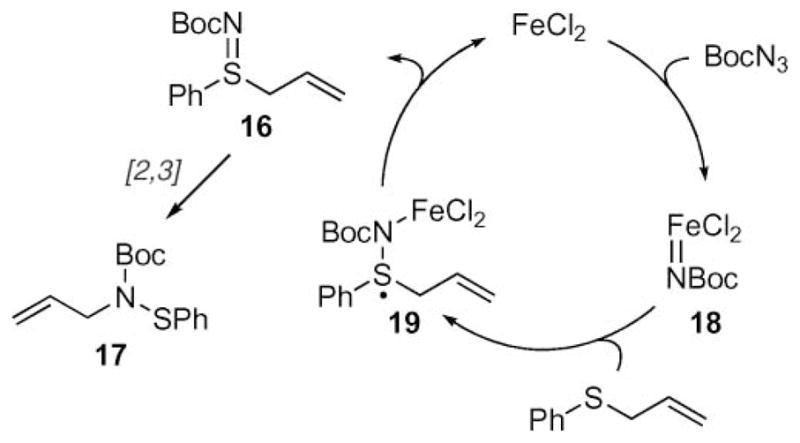

The synthetic potential of this transformation was realized when allylic sulfides were used as substrates (Scheme 4).26 Bach and co-workers reported that FeCl2-catalyzed N-atom transfer to the allylic sulfide was followed by a facile [2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement to efficiently produce α-substituted allylic amines 17 in a stereochemically defined manner. While the functional group tolerance of this reaction was broad, the synthetic utility of this transformation was diminished by the low reactivity of chiral α-substituted allylic sulfides. Van Vranken and co-workers extended this reaction to include propargylic substrates to enable access to N-allenylsulfenamides (e.g. 17e).27

Scheme 4.

Bach reaction: tandem sulfimination–[2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement. adppeFeCl2 (10 mol%) used; see ref. 27.

The observed reactivity trends led the authors to report that the mechanism of this transformation involved a redox process (Scheme 5).26 Iron-mediated decomposition of Boc-azide produces iron nitrenoid 18, which is followed by a stepwise N-atom transfer to form 16 via the iron(III) intermediate 19. A subsequent [2,3] rearrangement furnishes the allylic amine. This stepwise mechanism accounts for the formation of the sulfonamide and ulfenamide by-products, which are commonly observed.

Scheme 5.

Proposed mechanism of the Bach reaction.

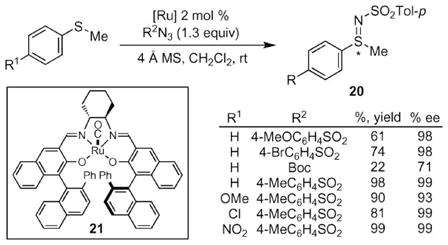

Since the initial report of this transfer reaction by Bach in 1998, synthetic efforts have been aimed at achieving the asymmetric N-atom transfer to sulfides. If allylic sulfides could be used, this reaction would enable the synthesis of chiral, non-racemic allylic amines from achiral sulfides. In 2001, Katsuki and co-workers reported that ruthenium salen complexes effectively catalyzed the sulfimidation of alkyl aryl sulfides with excellent enantioselectivity (eqn (1)).28,29 While several different arylsulfonyl azides exhibited excellent enantioselectivities, Boc-azide afforded the iminosulfide in reduced yield. This reaction tolerated a variety of functional groups including nitro- and methoxy groups, but was limited to aryl alkyl sulfides: benzyl methyl sulfide reacted slowly and with reduced selectivity.

|

(1) |

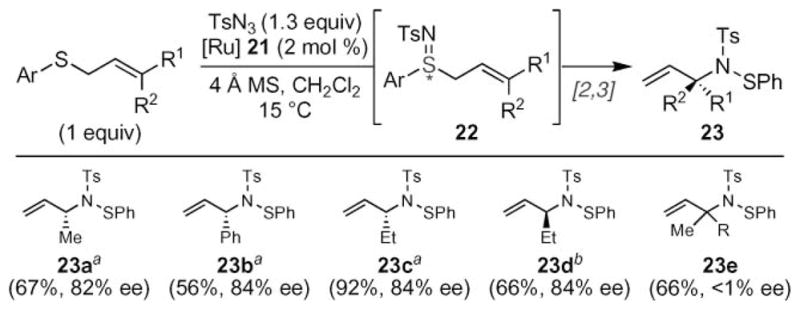

The enantioselective imidation of allylic sulfides using ruthenium salen complexes triggered a [2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement to produce allylic amines with enantioselectivities greater than 80% ee (Scheme 6).30 While the initial N-atom transfer to the sulfide occurred with % ee greater than 90%, some loss of optical activity occurred in the sigmatropic rearrangement. The resulting N-arylthioarylsulfonamides were hydrolyzed to allylic amines upon exposure to KOH in methanol without loss of optical activity. The reaction tolerated a broad range of aryl sulfide substituents as well as either E- or Z-olefin substituents. Importantly, the reaction was stereospecific: the chirality of 23c and 23d depended on the identity of the olefin isomer. Since nitrenoid transfer to the starting allylic sulfide was identical for either the E- or Z-isomer, the authors interpreted these results to indicate that the transition state of the subsequent [2,3] rearrangement is unique to the starting olefin isomer. While trisubstituted olefins did participate in the reaction, no chiral induction of the [2,3] rearrangement was observed. The lack of stereoselectivity led the authors to conclude that multiple reaction mechanisms are possible in the rearrangement.

Scheme 6.

Asymmetric tandem sulfimination–[2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement. aAllyl sulfide approximately a 90 : 10 mixture of E : Z. bAllyl sulfide approximately a 10 : 90 E : Z.

Transition metal-catalyzed N -atom transfer to olefins

Aziridination

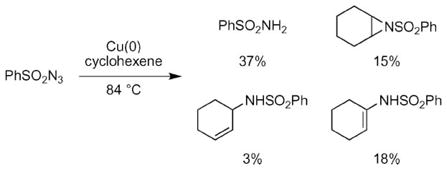

In 1967, Kwart and Khan reported the first metal-catalyzed nitrogen-atom transfer from an azide to an olefin (eqn (2)).31 They reported that copper powder promoted the decomposition of benzenesulfonyl azide in cyclohexene. In addition to cyclohexene aziridine, they also obtained C–H amination products as well as benzenesulfonamide. The product distribution is consistent with a nitrene or metal nitrenoid reactive intermediate.32 A radical mechanism could also account for the observed products.33 After these reports, Migita and co-workers reported palladium-catalyzed N-atom transfer reactions to olefins,34 and Groves and co-workers reported a stoichiometric N-atom transfer from a nitridomanganese(V) porphyrin to cycloalkenes.35

|

(2) |

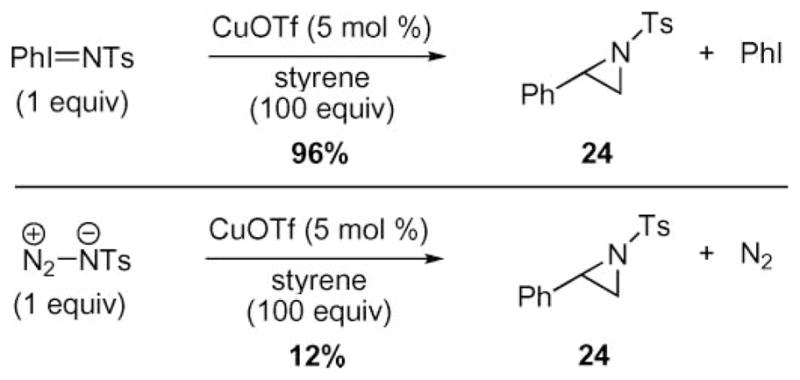

After these seminal reports, the use of iminoiodinanes supplanted azides as nitrene precursors in metal-mediated N-atom transfer reactions to olefins.36 Evans and Faul and co-workers found that tosyl azide was not as effective of a nitrene precursor as Ph=NTs—use of the iminoiodinane produced phenyl aziridine 24 in 96% yield whereas, using tosyl azide as the nitrene precursor produced only a 12% yield of 24 (Scheme 7).36b36d These observations were subsequently echoed by Jacobsen and coworkers in their report of copper diimine-catalyzed aziridination of olefins.36c While these iodine(III) reagents dramatically improved the efficiency of N-atom transfer to olefins, they were not as atom economical or green as azides because a stoichiometric quantity of iodobenzene was also produced.

Scheme 7.

Comparison of the efficiency of copper-catalyzed nitrenoid transfer to styrene.

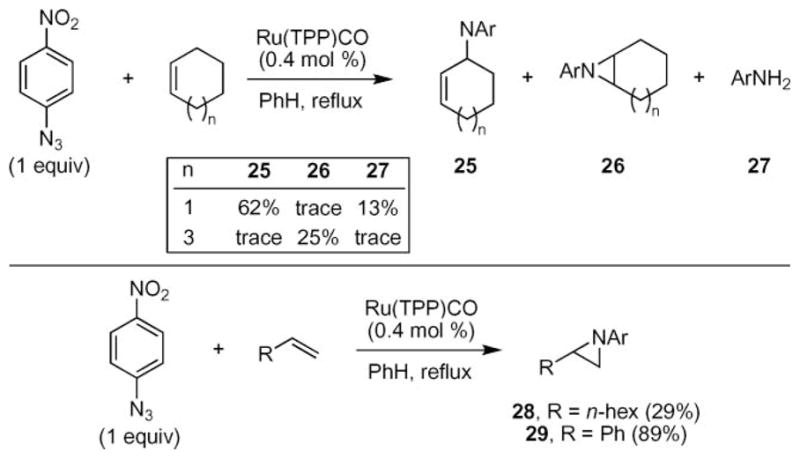

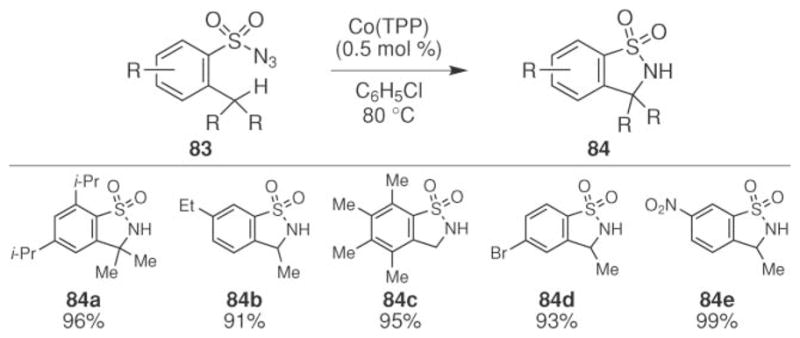

Inspired by the aforementioned reports of stoichiometric N-atom transfer from azides to olefins using transition metal porphyrins, Cenini and co-workers investigated the possibility of a catalytic reaction of aryl azides with olefins in the presence of metal porphyrin catalysts.37 An examination of a wide range of metal porphyrins revealed that nitrene transfer from p-nitrophenyl azide to cycloalkenes was catalyzed only by ruthenium- and cobalt complexes. The best results were obtained with ruthenium tetraphenylporphyrin (RuTPPCO) and cobalt octaethylporphyrin (CoOEP).38 The electronic nature of the aryl azide influenced the product distribution: when the nitro-group was substituted with a methoxy group, the only product observed was the corresponding aniline. Reduction of the aryl azide to the aniline is a common byproduct observed in the thermal- or photochemical decomposition of azides.14 Formation of this product has been attributed to the intermediacy of a divalent nitrogen reactive intermediate.14,39

Using the most active ruthenium tetraphenylporphyrin complex, N-atom transfer to a variety of olefins was attempted (Scheme 8).37 Similar to the results of Kwart and Khan,31,32 a range of products were observed for cyclohexene. Switching the olefin to cyclooctene resulted in the formation of aziridine 26 as the major product in 25% yield. The major by-products were p-nitroaniline and the azo compound. Monosubstituted olefins also produced aziridines as the major product: 1-hexene formed aziridine 28 in 29% yield. Substrates lacking α-protons provided more promising results: styrene afforded 29 as the only product in 89% yield. trans-Stilbene, on the other hand, did not produce any amination products.

Scheme 8.

Ruthenium porphyrin-catalyzed aziridine formation from aryl azides.

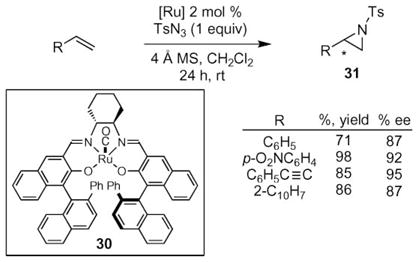

Substantial research effort by the Katsuki and Zhang groups has resulted in the development of methods that achieve the asymmetric formation of aziridines from monosubstituted styrenes with excellent yields and very good enantioselectivities. Prior to their work, two seminal reports by Jacobsen and Mueller,36c,40 established that asymmetric N-atom transfer from azides to olefins could be achieved with modest enantioselectivities. Katsuki and co-workers reported that the asymmetric formation of aziridines from sulfonyl azides could be achieved using a chiral ruthenium(II) salen complex (eqn (3)).41 This complex was previously shown to catalyze the formation of iminosulfides with excellent enantioselectivities and large turnover numbers. Because iminosulfide formation was believed to occur via N-atom transfer, the authors anticipated that aziridines could be formed from nucleophilic olefins. N-Tosyl aziridines were formed from terminal conjugated olefins with good yields and high enantioselectivity. Non-conjugated olefins (e.g. 1-octene) or trisubstituted olefins did not produce aziridines.

|

(3) |

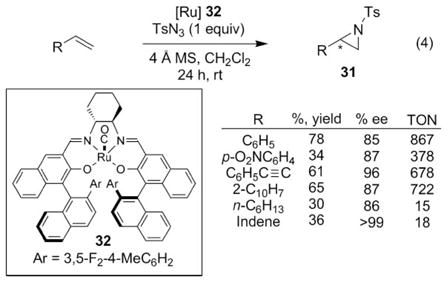

After examining crystal structures of 30, Katsuki and coworkers designed a new ruthenium(II) salen complex, 32, which they anticipated would be a more reactive aziridination catalyst that would suppress the undesired allylic C–H bond amination reaction.42 A crystal structure of 30 showed that the meta-hydrogens on the phenyl group were close (3.59 Å) to the N-atom of a bound acetonitrile ligand. Since acetonitrile would be replaced with the nitrene group when exposed to an azide, the meta-hydrogens might react with the nitrene to decompose the catalyst. Replacing these meta-hydrogens with fluorine atoms would render the catalyst more robust by eliminating this potential decomposition pathway. In line with this hypothesis, higher turnover numbers (TON) without attenuation of enantioselectivity was observed when ruthenium salen 32 was used to catalyze the aziridination of terminal olefins (eqn (4)). For the aziridination of para-nitrostyrene, a turnover number of 5 was observed using 30, whereas, a TON of 34 was observed using the fluorinated 32.

|

(4) |

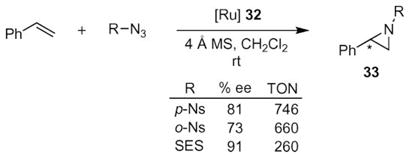

One weakness these aziridination reactions share is that efficient reaction rates occurred only when para-tolylsulfonyl azide was used. Relatively harsh conditions (e.g. NaNp, DME)43 are required to remove this group from the aziridine product. The discovery of a more active and robust catalyst enabled the Katsuki group to examine other azides bearing more easily removable groups on nitrogen (eqn (5)).44,45 They examined nitrobenzenesulfonyl azide (NsN3) and 2-(trimethylsilyl)ethanesulfonyl azide (SESN3) as a potential sources for the nitrenoid because both the p-Ns-group46,47 and SES-group48,49 can be removed under mild conditions. While both azides were shown to be competent sources of nitrene, higher enantioselectivities were observed when SES–N3 was used. Significantly higher turnover numbers, however, were obtained using p-NsN3 —up to 746 as compared to 260 for SESN3.

|

(5) |

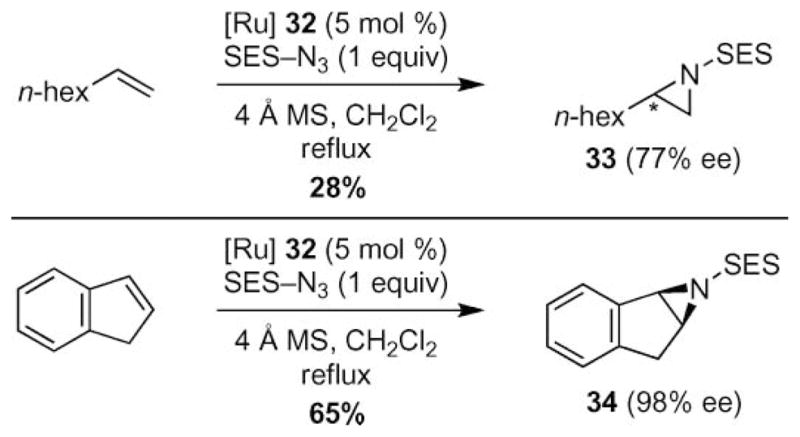

With this more reactive catalyst, aziridination of non-conjugated olefins could be achieved (Scheme 9).42,45 The fluorinated ruthenium salen complex (32) successfully catalyzed the formation of aziridines 33 and 34 from alkyl substituted alkenes although higher temperatures were required (eqn (4)). No competing allylic C–H bond amination was reported under these conditions. Even disubstituted alkenes, such as indene, were competent substrates.

Scheme 9.

Increased substrate scope with perfluorinated ruthenium–salen 32 catalyst.

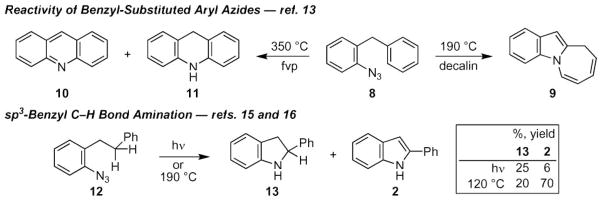

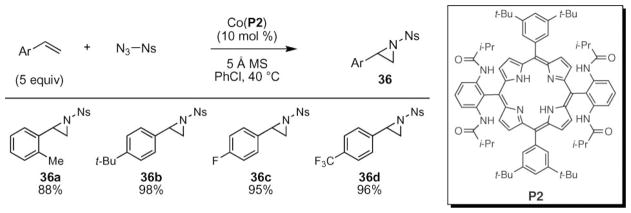

The Zhang group has pursued complementary approaches to the synthesis of chiral aziridines from azides. Like the Katsuki group, Zhang and co-workers have been motivated to develop a reaction wherein the product aziridine contains an easily removable group on nitrogen. Towards this end, they have developed several aziridination methods that employ diphenylphophoryl- or nosyl azide.

The Zhang group chose diphenylphosphoryl azide as their nitrogen-atom source because the nitrogen–phosphorous bond in the product aziridine is readily hydrolyzed.50–52 Low catalyst loads and high chemical yields were realized when a D2-symmetric chiral porphyrin was used as a ligand for cobalt (Scheme 10).52 This ligand contains chiral, non-racemic cyclopropyl-substituted amide side chains, which prevent the cobalt amido complex from decomposing in the reaction. It is easily synthesized from a tetrabromo-substituted porphyrin through a palladium-catalyzed quadruple amidation.53 While the asymmetric induction for diphenylphosphoryl N-atom transfer was moderate, it does represent a launching point for future method development.

Scheme 10.

Asymmetric cobalt-catalyzed aziridination of styrenes using phosphoryl azide. a20 mol% DMAP added.

Increased yields and broader substrate scope was observed when the azide substituent was changed from diphenylphosphoryl to sulfonyl.54 For this transformation, a non-chiral tetraamide porphyrin P2 was used as the ligand on cobalt. While cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin did not react with the sulfonyl azide, efficient N-atom transfer was obtained with the cobalt P2 porphyrin complex. A variety of substituted styrenes were reported to demonstrate the broad scope of their method (Scheme 11). They found that changing the electronic- or steric nature of the styrene did not lead to attenuated yields. Their optimized conditions tolerated substrates with ortho-substituents as well as strongly electron-withdrawing groups. N-Atom transfer from para-nosylazide was possible to a broader range of substrates than using diphosphoryl azide. One weakness of this system, however, was that aliphatic and disubstituted styrenes were not tolerated as substrates.

Scheme 11.

Scope of cobalt-catalyzed aziridination of styrenes using para-nosyl azide.

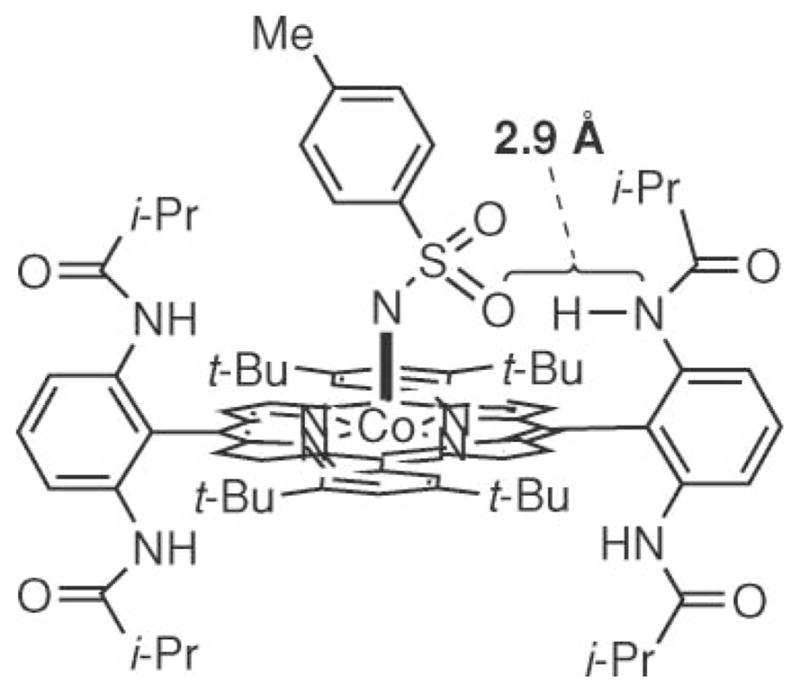

A model was suggested to account for the enhanced reactivity of the cobalt P2 complex.54 The cobalt porphyrin complex was designed to place the amide N–H bond close to the SO2 group present on the nitrene (Fig. 1). The subsequent hydrogen bond formation was anticipated to stabilize the formation of the postulated metal nitrenoid intermediate and enhance its electrophilicity. While no experimental evidence was provided to back up these assertions, computational modeling produced a minimal geometry of the cobalt nitrenoid that had an N–H–O bond distance of 2.9 Å. This short distance indicates that significant hydrogen bonding could occur between the nitrenoid and the amide. This hydrogen-bonding model may account for the increased reactivity of the cobalt P1 complex for the aziridination of styrenes with phosphoryl azide.

Fig. 1.

H-Bonding explanation for increased catalyst efficiency and lifetime.

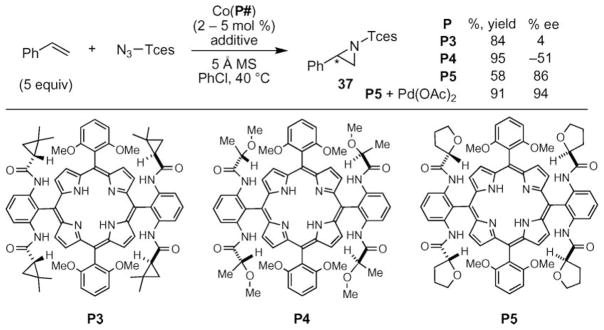

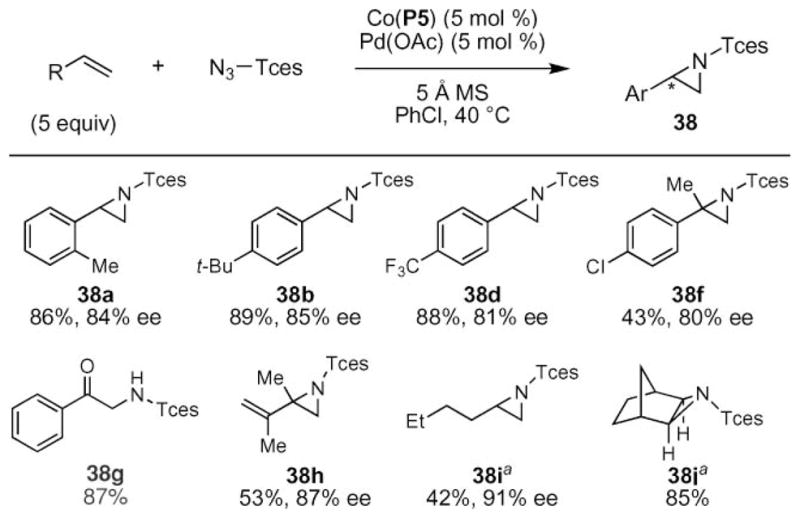

An important advance was realized by the Zhang group when they used their D2 symmetric cobalt porphyrin complex to catalyze the formation of aziridines from trichloroethoxysulfonyl (TCES) azide and an alkene (Scheme 12).55 In pursuit of discovering conditions that provided chiral aziridines with easily removable groups on nitrogen, the Zhang group found that trichloroethoxy-sulfonyl azide was a promising nitrene source. Optimization of the porphyrin ligand revealed that the highest yields and enantioselectivity could be achieved using porphyrin P5. While higher yields were observed using other D2-symmetric porphyrins, this porphyrin afforded the highest enantioselectivities. Examination of additives revealed that the addition of palladium acetate led to improved yields without loss of enantioselectivity.

Scheme 12.

Optimization of cobalt-catalyzed aziridination of styrene using Tces–azide.

These optimized conditions enabled a large range of alkenes to be transformed into aziridines with high yields and good enantioselectivities (Scheme 13). A screen of styrenes revealed that the electronic nature of the styrene did not affect the yield or selectivity of the process. The nitrenoid could be transferred to styrenes with ortho-substitution as well as gem-disubstituted styrenes to give 38e and 38f. For the latter substrates, attenuated yields were obtained without much diminishment of enantioselectivity. Even aryl-substituted silyl enol ethers could be used as substrates, as in 38g, although no enantioselectivity was observed. Even dienes and alkyl-substituted olefins were tolerated as substrates.55 This report by Zhang is the first to show that these substrates could be converted to aziridines without competing side reactions, such as dimerization of the nitrenoid and allylic C–H bond amination of the olefin.

Scheme 13.

Scope of cobalt-catalyzed aziridination of styrenes using Tces–Azide. aPdOAc2 (5 mol%) used.

Aminochlorination/aminoalkoxylation

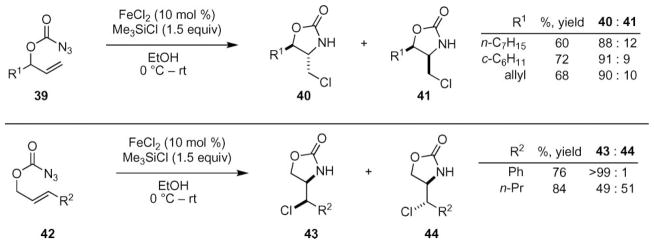

The intramolecular aminochlorination of an olefin can be achieved using substoichiometric amounts of iron(II) chloride to decompose azidoformates (Scheme 14).56,57 Bach and co-workers reported that monosubstituted alkenes 39 could be transformed to oxazolidinones diastereoselectively using 10–30 mol% of FeCl2 in the presence of a slight excess of trimethylsilylchloride (1.5 equiv). Irrespective of the R-group, the diastereoselectivity of the reaction was consistently about 9 : 1. Propargyl substrates are also tolerated as substrates. Insight into the mechanism of this transformation was gained from the reactivity of disubsituted alkenes 42. While nearly perfect stereochemical fidelity was obtained with a phenyl substituent, the n-propyl substrate afforded a 1 : 1 mixture of products.

Scheme 14.

Fe(II)-catalyed intramolecular aminochlorination of olefins.

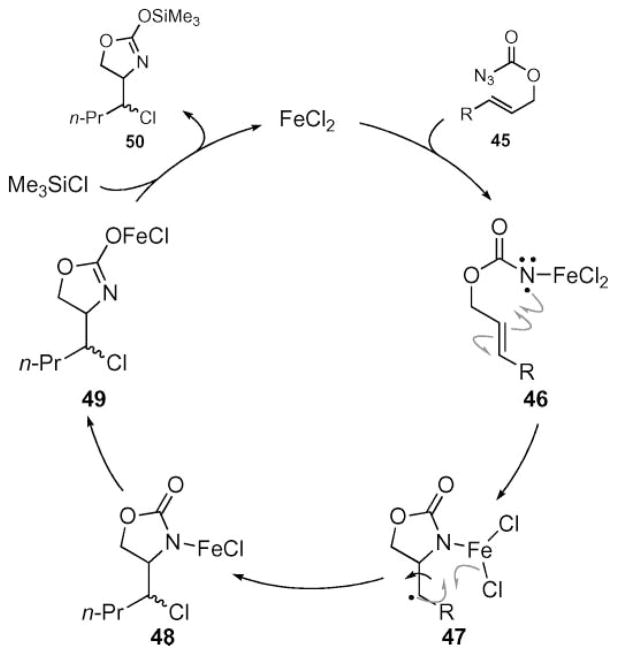

To account for the lack of stereospecificity, Bach and co-workers proposed a mechanism involving the intermediacy of radical intermediates (Scheme 15).56,57 Iron-mediated decomposition of the azidoformate produced Fe(III) nitrene 46, which underwent a 5-exo-trig cyclization to give 47. Even though chlorination was proposed to occur intramolecularly, this atom-transfer process occurred more slowly than bond rotation. Experiments to determine the lifetime of radical 47, were not successful.

Scheme 15.

Proposed mechanism of Fe(II)-catalyzed intramolecular aminochlorination.

C–H bond amination

Achieving the selective transformation of an unactivated C–H bond to a C–N bond would enable the rapid functionalization of readily available hydrocarbons. The use of azides as the nitrogen source in C–H bond amination reactions has motivated several research groups because the only by-product of C–N bond formation is N2. Azides also do not require additives to access divalent nitrogen, or to neutralize by-products of the activation. Together, these attributes simplify purification of the reaction mixture as well as ensure that the pH of the reaction remains constant to eliminate the need of base. Consequently, the resulting process has the potential to be quite environmentally benign if the appropriate solvent/catalyst pairing is discovered. Towards the goal of achieving selective C–H bond amination significant progress has been made in the functionalization of both sp2- and sp3-C–H bonds.

Functionalization of sp2-C–H bonds

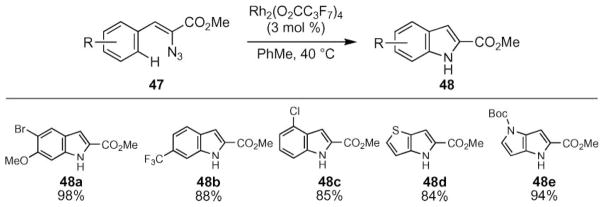

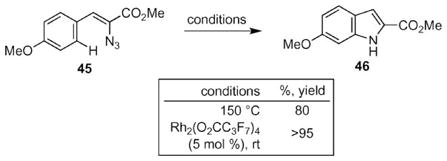

The Hemetsberger–Knittel–Moody indole reaction represents a rapid synthesis of 2-carboxylate-substituted indoles in two-steps from commercially available aryl aldehydes.10 Thermolysis of the vinyl azide substrate produces the indole in good yields. The Driver group reported that the rate of reaction could be accelerated by rhodium(II) perfluorobutyrate to form indoles at ambient temperature (eqn (6)).58 Other rhodium(II) tetracarboxylate complexes, such as Rh2 (OAc)4 and other transition metal salts (e.g. FeX2, ZnX2, CuX2, AgX, AuX) were found to be ineffective as catalysts.

|

(6) |

Rhodium(II) perfluorobutyrate proved to be an effective catalyst to enable the synthesis of a range of indoles 48 from vinyl azides 47 (Scheme 16). The reaction tolerated a variety of functional groups, including halogen-, trifluoromethyl-, and methoxy substituents as well thiophenes, furans, and pyrroles. The Lewis acidity of the rhodium(II) carboxylate limited the substrate scope to those that contained non-Lewis basic functional groups: azides bearing cyano-, and dimethylamino groups did not produce indoles.

Scheme 16.

Representative examples of rhodium(II)-catalyzed indole formation.

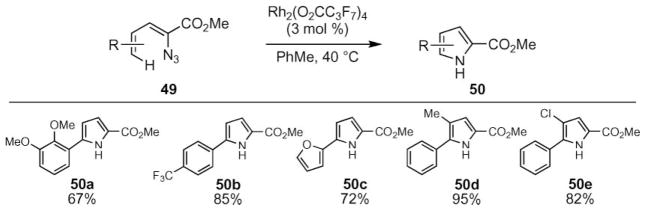

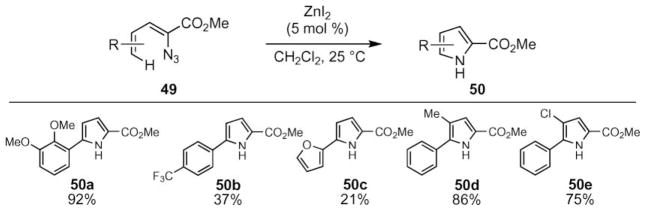

Rhodium(II)-catalyzed N-heterocycle formation was extended to include pyrroles (Scheme 17).59 The functional group tolerance of this reaction mirrored the indole reaction and a variety of di-and trisubstituted pyrroles could be produced in good yield.

Scheme 17.

Representative examples of rhodium(II)-catalyzed pyrrole formation.

In contrast to indole synthesis, a variety of transition metal salts were able to catalyze pyrrole formation (Scheme 18).59 In addition to rhodium(II) carboxylates, copper(II) triflate and zinc iodide were found to be competent catalysts. In the presence of 5 mol% of zinc iodide, the pyrrole formation occurred readily at room temperature. Comparison of reaction conversions revealed different substrate preferences: higher yields were obtained with dienylazides bearing electron-deficient aryl groups using rhodium perfluorobutyrate (50b, 50c), while zinc iodide was preferred for substrates with electron-donating dienyl azide substituents (e.g. 50a).

Scheme 18.

Representative examples of zinc-catalyzed pyrrole formation.

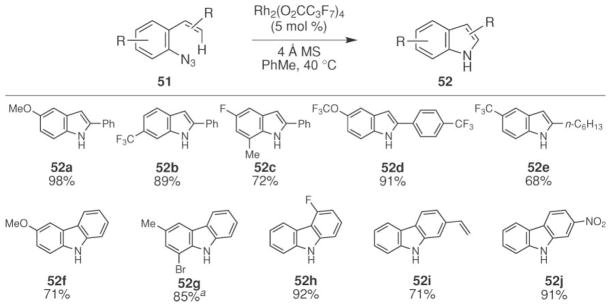

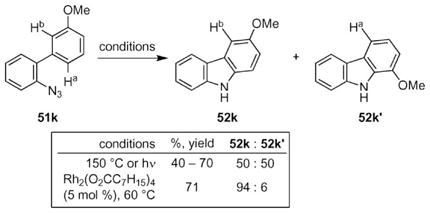

The Driver group also developed a complementary synthesis of N-heterocycles with C2-aryl or alkyl substituents from aryl azides 51 through the construction of the C2 C–N bond (Scheme 19).60 While the analogous thermal and photochemical reactions are known,11 they are rarely used to make N-heterocycles because the rate of decomposition of the aryl nitrene competes61 with the desired C–H amination reaction. Using rhodium(II) perfluorobutyrate or octanoate as catalyst, a range of indoles (52) were formed at 60 °C from aryl azides (51). In addition to indoles, a variety of carbazoles could be formed from the corresponding biaryl azides.62

Scheme 19.

Representative examples of rhodium(II)-catalyzed indole and carbazole formation from aryl azides. aReaction performed on multi-gram scale.

Examination of the reactivity of biaryl azides revealed a significant advantage to using rhodium(II) carboxylates as catalysts to form N-heterocycles (eqn (7)).62 Thermolysis or photolysis of biaryl azide 51k produced a nearly 50 : 50 mixture of the two possible carbazoles.12 In contrast, rhodium(II) octanoate significantly improved the selectively to form carbazole 52k as the major product. The Driver group interpreted this selectivity as evidence that the metal complex was involved in the C–N bond forming step of the mechanism.

|

(7) |

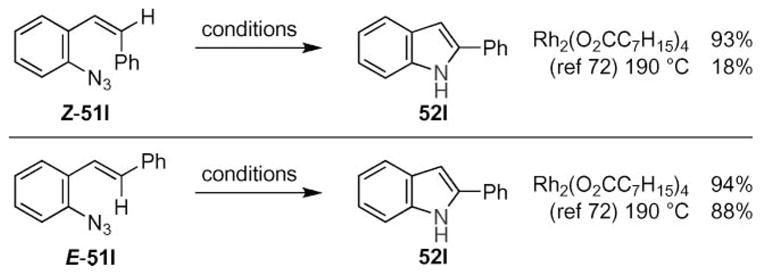

Further insight into the mechanism was obtained from the observed reactivity of both the E- and Z-styryl azide isomers 51l (Scheme 20). While the E-isomer was found to readily produce 2-phenylindole, Smith and co-workers reported that thermolysis of the Z-isomer resulted in the formation of a tarry substance in addition to a significantly lower yield of indole.63 In contrast, exposure of either the E- or the Z-isomer to 5 mol% of rhodium(II) carboxylate produced 2-phenylindole cleanly. The Driver group interpreted this result as evidence that indole formation occurred through a stepwise process where C–N bond formation preceded C–H bond cleavage.

Scheme 20.

Stereospecificity of rhodium(II)-catalyzed indole formation from aryl azides.

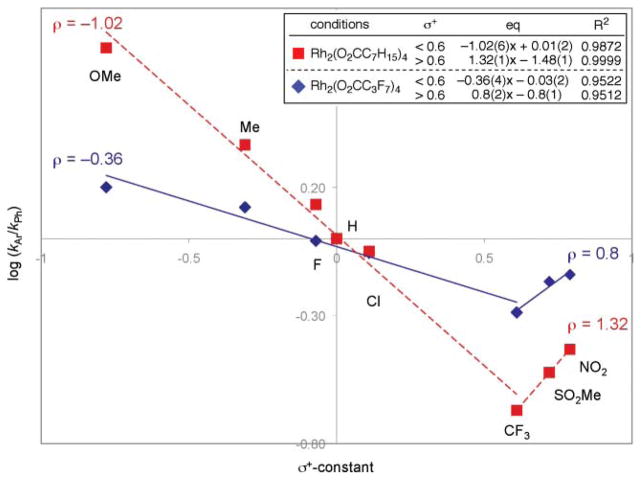

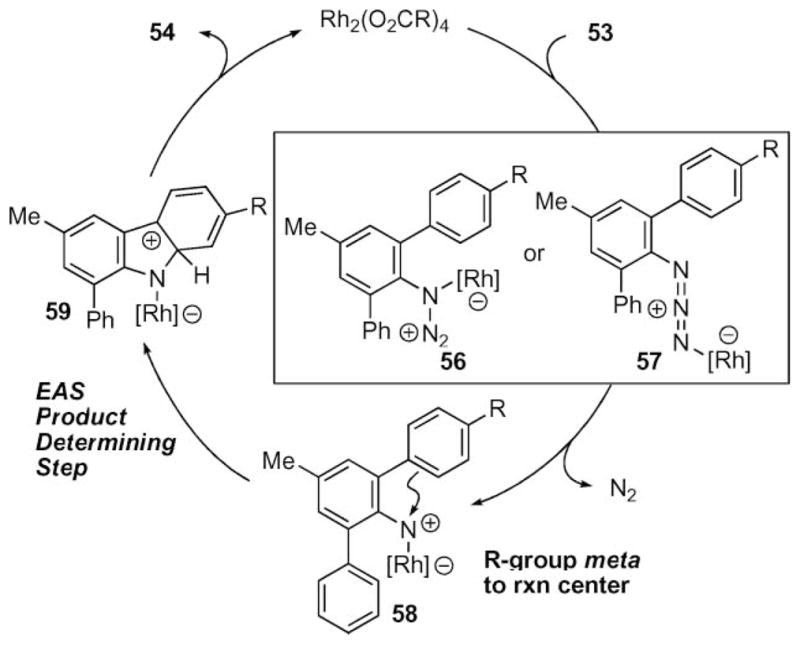

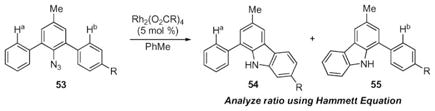

Further insight into the mechanism came from a study on the reactivity of triaryl azides 53 (eqn (8)).64 The ratio of products would be analyzed using the Hammett equation, and the results were anticipated to provide insight into the nature of C–N bond formation. The original hypothesis was that C–N bond formation occurred through electrophilic aromatic substitution and a linear correlation to σmeta-constants was expected. Because the methoxy-group is at the meta-position to the reaction center, it would act as an inductive electron-withdrawing group if an electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS) mechanism was occurring (Scheme 21).

Scheme 21.

Disproven electrophilic aromatic substitution mechanism for carbazole formation.

|

(8) |

In contrast to these expectations, no correlation with σmeta-constants was observed. On the basis of this data, electrophilic aromatic substitution was eliminated as the mechanism for C–N bond formation. Instead, bisecting straight lines were observed when the product ratios were plotted against Hammett σ+-constants (Fig. 2).65 Related V-shaped graphs have been interpreted as evidence for a change in the identity of the rate-determining step, or as evidence that a change in the mechanism is occurring.66

Fig. 2.

Relationship of carbazole product ratio with Hammett equation.

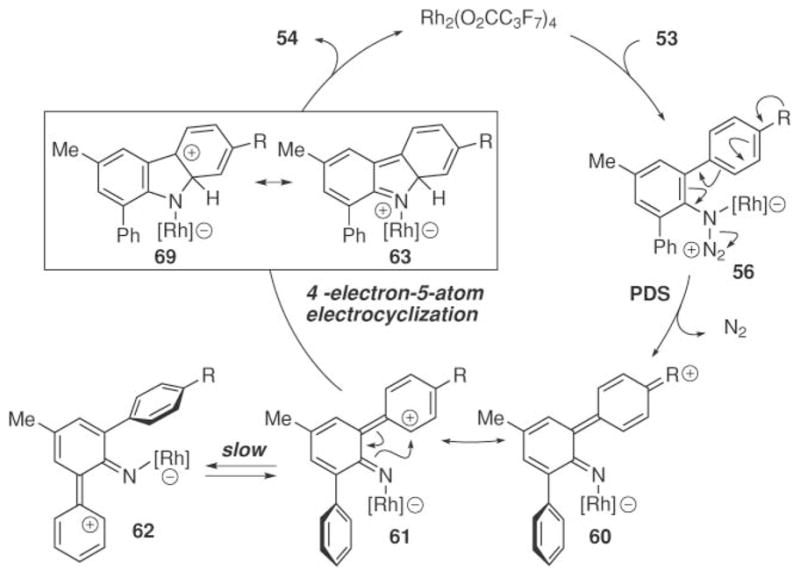

The Driver group interpreted the correlation with σ+-constants as evidence that the product-determining step occurred before C–N bond formation (Scheme 22). Linear correlation with σ+- constants would be expected if the more electron-rich aryl group assists in the formation of the rhodium nitrenoid (56 to 60). Considering the rhodium nitrenoid as ortho-azaquinoid 60 provides an explanation for the selectivity in C–N bond formation. A resonance structure of the resulting ortho-azaquinoid (61) places the positive charge on the ortho-carbon to trigger a four-π-electron-five-atom electrocyclization67 to form the C–N bond in 69. This electrocyclization must occur faster than tautomerization of the metalloimine (61 to 62),68 which would abolish selectivity in C–N bond formation. A 1,5-hydride shift from 63 then affords the carbazole product.

Scheme 22.

4π-Electron-5-atom-electrocyclization mechanism for carbazole formation.

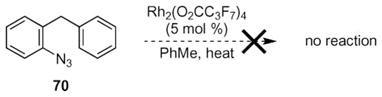

The requirement of a contiguous π-system was examined with 70 (eqn (9)). If electron assistance was required for rhodium nitrenoid formation, azide 70 was expected not to react. As anticipated, exposure 70 to reaction conditions resulted in no reaction.

|

(9) |

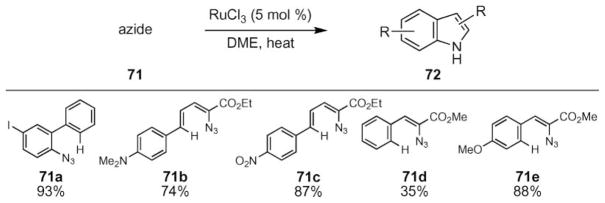

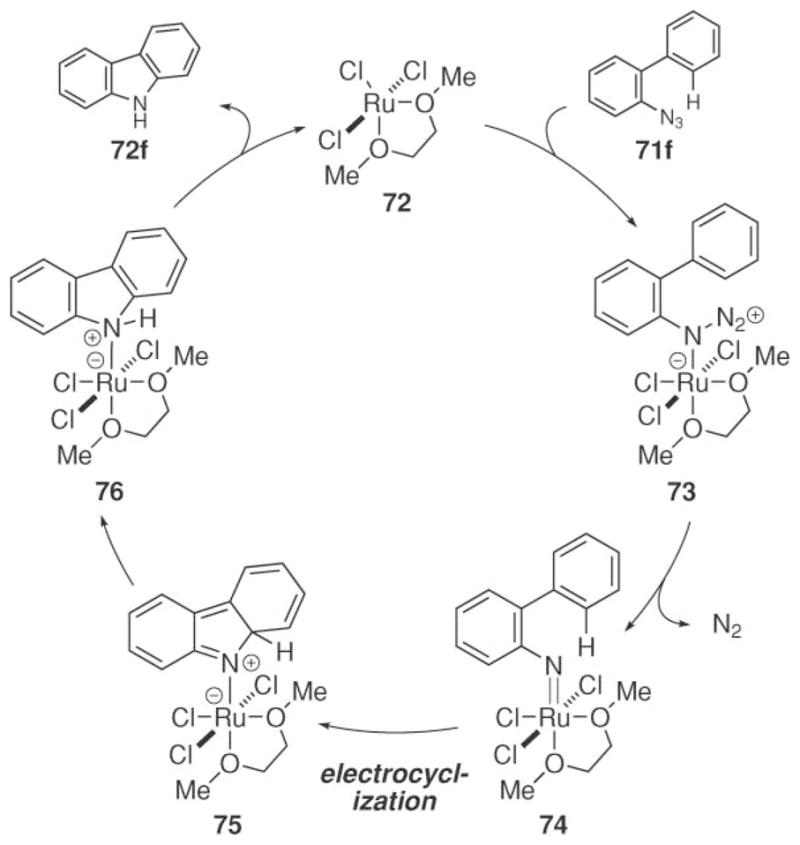

The Jia group recently reported that ruthenium trichloride could be used as a catalyst to promote N-heterocycle formation from aryl- and vinyl azides (Scheme 23).69 While carbazole and pyrrole formation occurred at 85 °C, slightly higher temperatures (105 °C) were required to form indoles from vinyl azides 71. In comparison to the use of rhodium(II) carboxylate complexes, slightly elevated temperatures were required to form the desired N-heterocycle. This limitation is mitigated by the significantly reduced cost of the catalyst and increased functional group tolerance of the reaction—Lewis basic groups such as dimethylamine (71b) were allowed. The stereoselectivity of this Ru-catalyzed N-heterocycle formation has not yet been reported.

Scheme 23.

Representative examples of ruthenium(III)-catalyzed N-heterocycle formation.

To provide insight into the mechanism of this process, density functional theory calculations were performed on a variety of possible reactive intermediates.69 The Jia group interpreted these calculations to suggest that a Ru(III)/Ru(V) catalytic cycle occurs and that the C–N bond is formed through a similar electro-cyclization mechanism as reported by Driver and co-workers (Scheme 24). In support of this mechanism, aryl azide 70 did not react when exposed to ruthenium trichloride.

Scheme 24.

Potential electrocyclization mechanism for ruthenium(III)-catalyzed carbazole formation.

Towards a general aliphatic C–H bond amination method

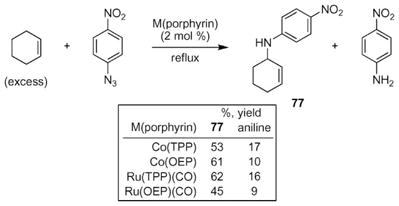

In 1999, ruthenium- and cobalt porphyrin complexes were reported by Cenini and co-workers to catalyze sp3-C–H bond amination reactions using para-nitrophenylazide as the source of the nitrogen-atom.37,38 While cycloheptene and cyclooctene were effectively converted to the corresponding aziridine, exposure of cyclohexene to either catalyst formed allyl amine 77 (eqn (10)). The major by-product was reduction of the azide to form para-nitroaniline. The product distribution was affected by the electronic nature of the aryl azide: when an electron-rich azide was used (e.g. p-methoxyphenylazide), the yield of allylic C–H bond amination was reduced.

|

(10) |

Cobalt(II)-catalyzed benzylic C–H bond amination was also investigated using para-nitrophenylazide (Scheme 25).70,71 While a variety of cobalt(II) porphyrins catalyzed the formation of amine 78, empirical evidence revealed that changing the hydrocarbon substrate required a screen of different porphyrin ligands to achieve the highest yield.

Scheme 25.

Cobalt-catalyzed sp3-C–H bond amination.

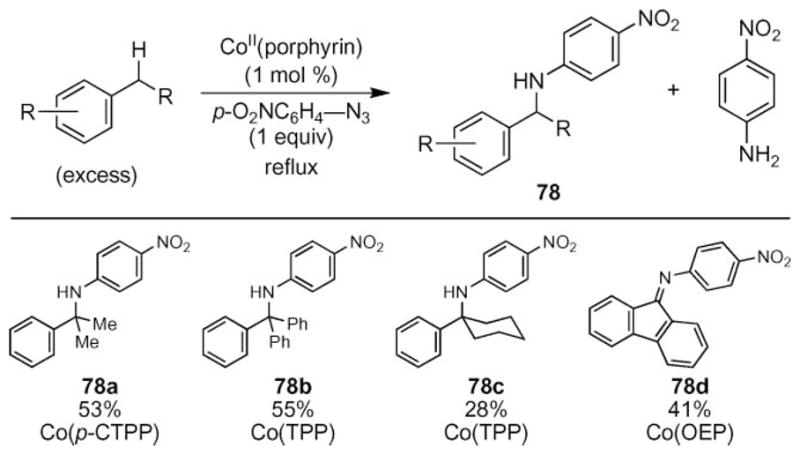

Further insight into the mechanism of allylic C–H bond amination came from the isolation of a ruthenium diimido complex 80 (Scheme 26).72 Exposure of ruthenium tetraphenyl porphyrin to aryl azide 79 resulted in the formation of diimido complex 80, whose structure was determined by X-ray crystallography.73 This complex catalyzed N-atom transfer from aryl azide to cyclohexene. Exposure of an excess of cyclohexene to 80 resulted in the formation of allylic amine 82 and 1,3-cyclohexadiene. X-Ray crystallography revealed that the ruthenium product was diamide complex 81. This complex was also a competent amination catalyst. Reaction of 81 and cyclohexene produced allylic amine and cyclohexane. The ruthenium was then oxidized to produce the diimide complex to complete the catalytic cycle. This data contrasts with the kinetic and mechanistic data obtained from Cenini’s previous study of cobalt porphyrin-catalyzed N-atom transfer to alkenes.38,71

Scheme 26.

Characterization and reactivity of ruthenium porphyrin reactive intermediates.

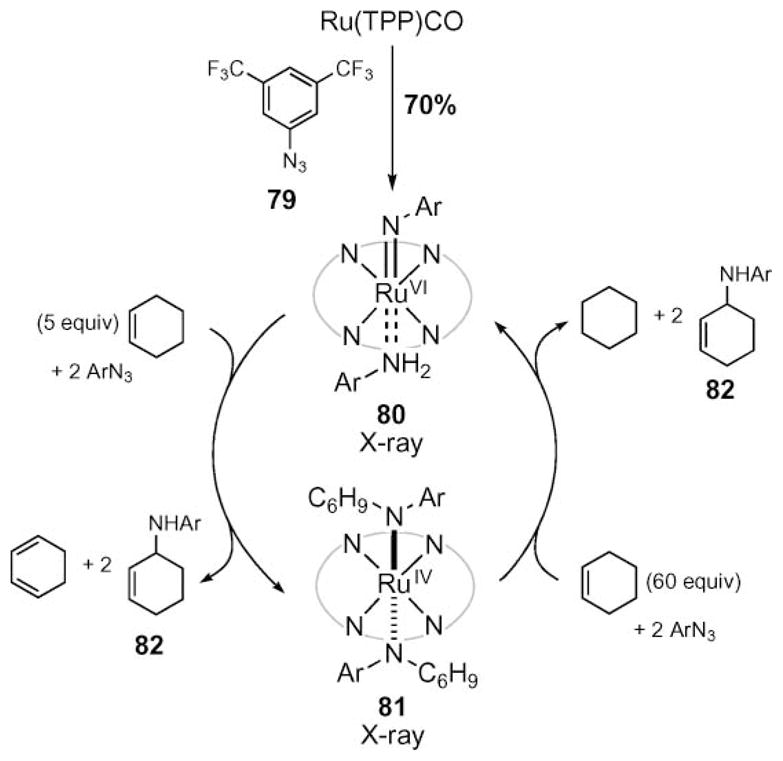

Significant advances in this field have been achieved by the Zhang group.74–76 They reported both intra- and intermolecular sp3-C–H bond amination using cobalt(II) porphyrin complexes. In 2007, they reported that cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin catalyzed the intramolecular amination of benzylic C–H bonds (Scheme 27).74 Cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin emerged as the best catalyst from a series of transition metal porphyrin complexes. No reaction, or in-efficient reaction rates were observed using vanadium(IV), iron(III), copper(II), chromium(III), zinc(II), manganese(III), nickel(II), or ruthenium(II) porphyrin complexes. The optimal reaction conditions were determined to only require 0.5 mol% of Co(TPP) to decompose the aryl sulfonyl azide. The scope of benzyl C–H bond amination was found to be broad. Tertiary-, secondary-, and primary C–H bonds could be functionalized to produce N-heterocycle 84. In addition to alkyl groups, the reaction also tolerated bromo- and nitro-substituents.

Scheme 27.

Cobalt-catalyzed intramolecular sp3-C–H bond amination of arylsulfonyl azides.

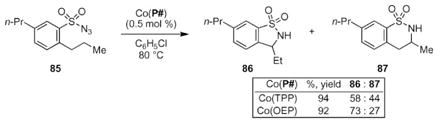

The Zhang group investigated the selectivity of their C–H bond amination by screening aryl sulfonyl azide 85 (eqn (11)).74 The Du Bois group has reported that the related sulfonamide nitrenoid rhodium complexes prefer reaction with C–H bonds to form six-membered N-heterocycles.77 To compare the selectivity of their cobalt-catalyzed process, the Zhang group investigated 85, which contains two reaction centers. Amination of the weaker benzylic C–H bond would produce a five-membered ring, whereas reaction with the β-C–H bond would produce a six-membered ring. The Zhang group reported that the ratio of 86 to 87 depended on the identity of the porphyrin ligand, with Co(OEP) promoting a more selective reaction. Control of the product ratio indicates that the metal complex is involved in the C–N bond-forming step of the mechanism.

|

(11) |

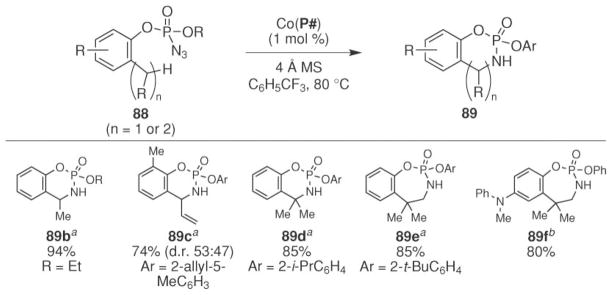

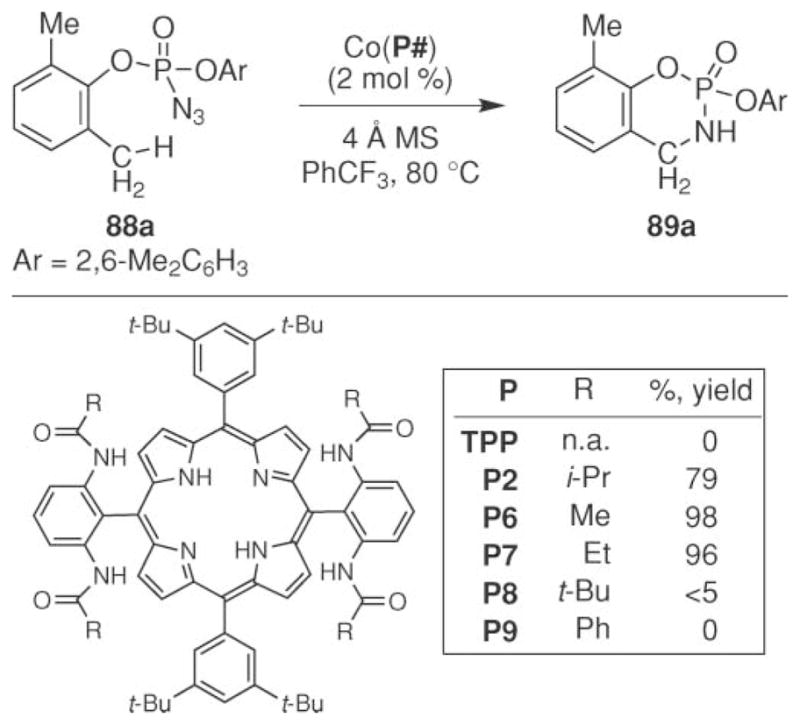

The Zhang group also reported that intramolecular benzylic C–H bond amination could be accomplished from aryl phosphoryl azides (Scheme 28).75 The optimal reaction conditions were determined using azide 88a. The Zhang group found that the reaction efficiency strongly depended on the identity of the porphyrin ligand. In contrast to their sulfonyl azide study, cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin was found to be inactive. Instead, effective conversion to phosphoramidite 89a was accomplished using the catalyst formed from porphyrins P2, P6, or P7. The higher activity of these complexes was attributed to their participation in hydrogen bonding of the amide N–H with the oxide of the phosphoryl group on the nitrenoid.54 The yield of the process depended on the steric nature of the R group on the amide. The highest yields were observed with a methyl- or ethyl substituent. Increasing the size of the amide (R =i-Pr) resulted in a diminished yield. Further increasing the size to a t-Bu group completely inhibited the reaction. No product formation was also observed with an N-phenylamide (P9) ligand.

Scheme 28.

Cobalt-catalyzed intramolecular sp3 C–H bond amination of arylphosphoryl azides.

The scope of this reaction was quite broad (Scheme 29).75 The reaction could form either a six- or a seven-membered ring, the latter ring size being particularly noteworthy for C–H bond amination because it is rarely observed. Six-membered phosphoramidites could be formed in high yield from primary, secondary-, or tertiary benzylic C–H bonds. The successful conversion of 88c revealed that aziridination was not a competitive reaction. Even phosphoryl azides containing Lewis basic groups such as a tertiary amine (88f) were competent substrates. If the benzylic position was fully substituted, seven-membered ring formation readily occurred without increasing the catalyst loading or reaction temperature. The cyclic phophoramidite amination products can be reduced with LiAlH4 or methanolyzed to produce value added amine-containing products.75

Scheme 29.

Cobalt-catalyzed intramolecular sp3 C–H bond amination of arylphosphoryl azides. a2 mol% Co(P6) used. b2 mol% Co(P2) used.

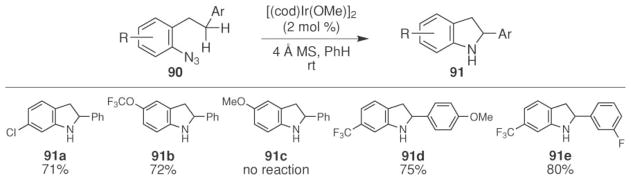

In addition to phosphoryl- and sulfinylazides, intramolecular benzylic C–H bond amination of aryl azides is also possible. The Driver group found that iridium(I) catalyzed the formation of indolines 91 from electron-deficient aryl azides 90 at room temperature (Scheme 30).16 Cyclooctadiene iridium methoxide dimer was identified empirically from a screen of nearly 200 different transition metal salts and complexes known to catalyze the functionalization of C–H bonds. Indoline formation was sensitive to the electronic nature of the starting azide. While electron-deficient aryl azides were efficiently converted, no reaction was observed with electron-rich substrates. In contrast, the reaction was not affected by the electronic nature of the β-aryl substituent: good conversions were observed with both electron-rich and electron-poor substituents. One weakness of this method was the strict requirement for Schlenk experimental techniques: in the absence of rigorous air and water exclusion, the major product of the reaction was aniline.

Scheme 30.

Iridium(I)-catalyzed indoline formation from aryl azides.

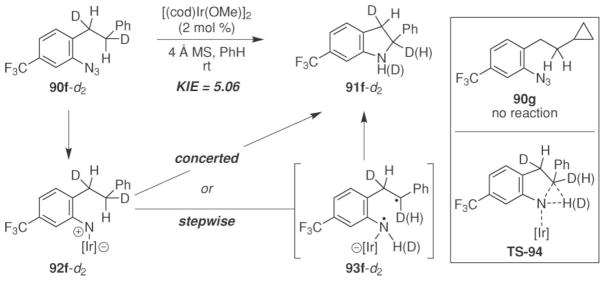

A primary kinetic effect was observed in the intramolecular competition experiment of 91f- d2 (Scheme 31). 16 Driver and co-workers interpreted this result as evidence that C–H bond amination occurred stepwise through either an H-atom abstraction–radical recombination through diradical 93f-d2 or a concerted mechanism via TS-94. Unfortunately, the lack of reactivity of the cyclopropyl-substituted 90g prevented further mechanistic conclusions to be drawn.

Scheme 31.

Potential mechanisms for Ir(I)-catalyzed indoline formation.

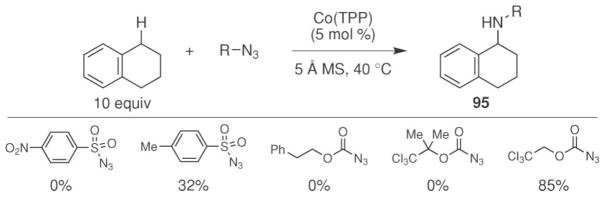

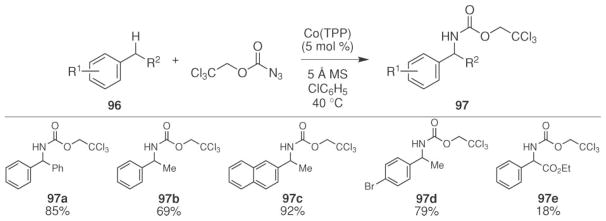

An important advance was realized by the Zhang group when they reported that intermolecular C–H bond functionalization could be achieved using Troc-azide as the N-atom source and the commercially available cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin complex as the catalyst (Scheme 32).76 To achieve this intermolecular reaction, a range of azides were screened as potential nitrogen-atom sources. Only tosyl-azide and Troc-azide were found to be competent starting materials and significantly higher yields were observed with Troc-azide. The facile removal of the Troc-protecting group from the product amine is another significant advantage offered by this process.78 This N-atom transfer reaction was sensitive to the electronic- and steric nature of the azide. Replacing the methyl group on the sulfonyl azide with a nitro group inhibited the reaction. Increasing the steric nature of the Troc-azide by adding two methyl substituents also resulted in no reaction.

Scheme 32.

Cobalt-catalyzed intermolecular benzylic C–H bond amination.

The scope of the reaction was examined using Troc-azide as the N-atom source (Scheme 33).76 The reaction worked best for the functionalization of secondary benzylic C–H bonds. Attenuating the electron density of the aryl substituent led to a slightly reduced yield (97d), whereas adding an ester group to the benzylic carbon (97e) led to a significantly lower yield. No reaction was observed with substrates containing primary benzylic C–H bonds (e.g. toluene) or non-benzylic C–H bonds (e.g. cyclohexane).

Scheme 33.

Scope of cobalt-catalyzed intermolecular benzylic C–H bond amination using Troc-N3.

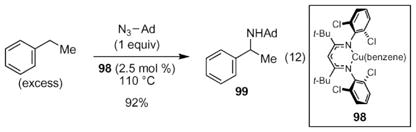

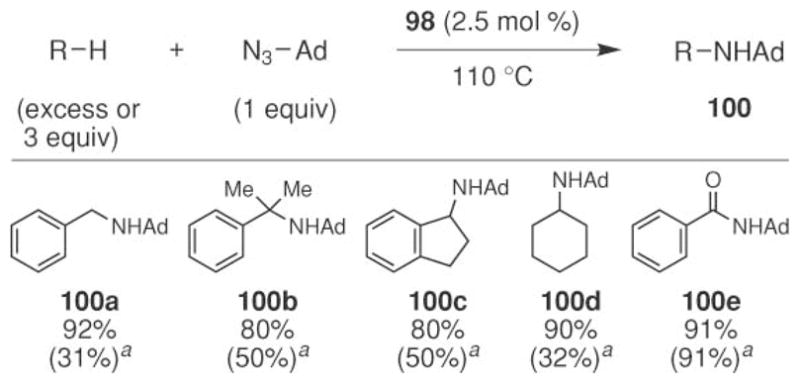

Intermolecular nitrene transfer was also recently reported by the Warren laboratory using a copper ketiminate complex 98 (eqn (12)).79 While this complex is not commercially available, it can be synthesized from Cu(Ot-Bu)2 using inert experimental techniques from copper tert-butoxide.80,81 The catalyst was quite selective: the reaction of ethylbenzene with adamantyl azide produced only benzyl amine 99.

|

(12) |

A variety of hydrocarbons were screened to investigate the scope of this reaction (Scheme 34).79 While higher yields were observed with secondary benzyl C–H bonds than primary or tertiary C–H bonds. For primary C–H bonds, the product amine reacted to afford adamantyl aldimine 100e. In addition to benzyl C–H bonds, cyclohexane could be converted to cyclohexyl amine. For this substrate, slightly longer reaction times were required. While excellent yields were observed if the reaction was performed neat in hydrocarbon, lowering the amount of the substrate to one equivalent resulted in diminished yields for toluene and cyclohexane. For more reactive C–H bonds (such as secondary benzylic C–H bonds) the yield was not as attenuated.

Scheme 34.

Scope of copper-catalyzed intermolecular sp3 C–H bond amination using adamantyl azide. a3 equiv of the alkane used.

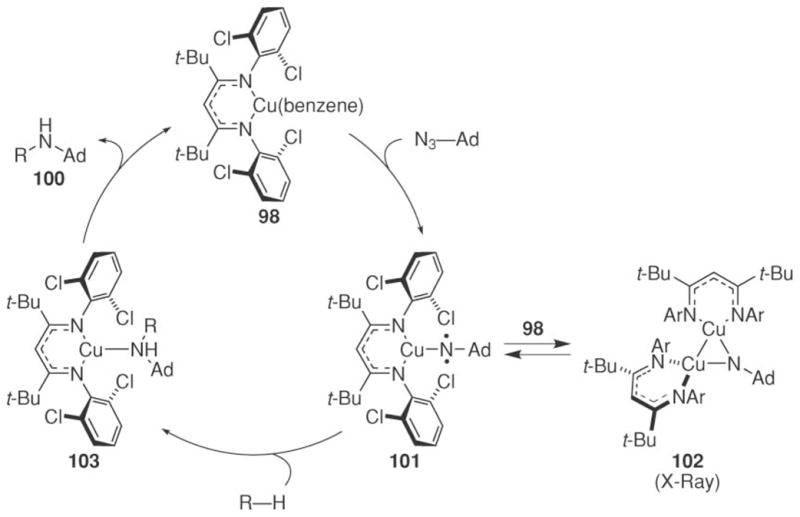

A catalytic cycle for this process was postulated on the basis of several isolated copper species (Scheme 35).79 Reaction of copper ketiminate with adamantyl azide forms copper nitrenoid 101. This species can react with an additional copper ketiminate to produce the isolable 102, or with a C–H bond to produce the copper amine 103. Dissociation of the amine regenerates the copper ketiminate complex. Density functional theory calculations were performed to investigate the nature of copper nitrenoid 101. The ground state of 101 was determined to be a singlet biradical and to exist 18 kcal mol−1 below the triplet state.

Scheme 35.

Potential mechanism for copper-catalyzed C–H bond amination of hydrocarbons.

Conclusions and future outlook

Substantial progress has been made in the development of transition metal-catalyzed N-atom transfer reactions using azides as the nitrogen-atom precursor. The attractiveness of azides in these processes stems from their ready accessibility, controllable reactivity, and environmentally benign by-products. High yields, good selectivities, and broad substrate scope prove that azides are excellent choices for the nitrenoid precursor in aziridination and sulfimination reactions. Because these reactions can be catalyzed by a range of different transition metal complexes, the reaction conditions can be tailored to match the demands of the process. Considerable strides have also been made using azides in C–H bond amination processes. Intramolecular processes that form new C–N bonds are appealing, alternative methods for the construction of N-heterocycles. Selective intermolecular C–H amination processes are just emerging and represent future targets for the development of new chemistry, which use azides with easily removable groups on nitrogen. Achieving transition metal-catalyzed intra- and intermolecular asymmetric C–H bond amination reactions also remains a future goal in this area. Tandem processes triggered by an initial N-atom transfer from azides to create multiple bonds also remain underdeveloped. The positive attributes of using azides will insure continued research interest for their use in N-atom transfer reactions.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health NIGMS (R01GM084945), Petroleum Research Fund administered by the American Chemical Society (46850-G1), and the University of Illinois at Chicago are acknowledged for their generous support of our research program. Mr. Benjamin J. Stokes is thanked for assistance in the preparation of this perspective.

Biography

Tom G. Driver is an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He received his Bachelor’s degree with L. K. Montgomery (Indiana University, 1999), and is his doctoral degree with K. A. Woerpel (University of California, Irvine, 2004). After a Ruth L. Kirschstein NIH funded postdoctoral fellowship with John E. Bercaw and Jay A. Labinger (Caltech, 2006), he started his independent academic career at UIC. Currently, the Driver group is focused on the development of new transition metal-catalyzed methods that create heterocycles from azides.

Tom G. Driver is an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He received his Bachelor’s degree with L. K. Montgomery (Indiana University, 1999), and is his doctoral degree with K. A. Woerpel (University of California, Irvine, 2004). After a Ruth L. Kirschstein NIH funded postdoctoral fellowship with John E. Bercaw and Jay A. Labinger (Caltech, 2006), he started his independent academic career at UIC. Currently, the Driver group is focused on the development of new transition metal-catalyzed methods that create heterocycles from azides.

References

- 1.For recent reviews on the reactivity of azides, see: Bräse S, Gil C, Knepper K, Zimmermann V. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:5188. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400657.Scriven EFV, Turnbull K. Chem Rev. 1988;88:297.L’abbé G. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1975;14:775.

- 2.(a) Grieβ P. Philos Trans R Soc London. 1864;13:377. [Google Scholar]; (b) Grieβ P. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1865;50:275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For reviews, see: Becer CR, Hoogenboom R, Schubert US. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:4900. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900755.Meldal M, Tornøe CW. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2952. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479.Moses JE, Moorhouse AD. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1249. doi: 10.1039/b613014n.Bock VD, Hiemstra H, Maarseveen JHv. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:51.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:2004. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5.

- 4.For original reports of copper-catalyzed “click” reactions, see: Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:2596. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4.Tornøe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j.

- 5.For reviews, see: Dauban P, Dodd RH. In: Amino Group Chemistry. Alfredo R Professor., editor. 2008. pp. 55–92.Davies HML, Manning JR. Nature. 2008;451:417. doi: 10.1038/nature06485.Du Bois J. Chemtracts. 2005;18:1.Espino CG, Du Bois J. In: Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Wiley; 2005. pp. 379–416.Du Bois J, Tomooka CS, Hong J, Carreira EM. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:364.Mansuy D. Pure Appl Chem. 1990;62:741.

- 6.For recent leading reports, see: Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9220. doi: 10.1021/ja8031955.Liang C, Collet F, Robert-Peillard F, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:343. doi: 10.1021/ja076519d.Fiori KW, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:562. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450.Harden JD, Ruppel JV, Gao GY, Zhang XP. Chem Commun. 2007:4644. doi: 10.1039/b710677g.Lebel H, Huard K, Lectard S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14198. doi: 10.1021/ja0552850.Espino CG, Du Bois J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:598–600.Dauban P, Sanière L, Tarrade A, Dodd RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7707. doi: 10.1021/ja010968a.and references therein.

- 7.For recent reviews of azide in transition metal-catalyzed N-atom transfer reactions, see: Collet F, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Chem Commun. 2009:5061. doi: 10.1039/b905820f.Cenini S, Gallo E, Caselli A, Ragaini F, Fantauzzi S, Piangiolino C. Coord Chem Rev. 2006;250:1234. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801148.Katsuki T. Chem Lett. 2005;34:1304.

- 8.For a review on the syntheses of azides, see ref. 1b pp. 301–321.

- 9.For alternative N2 -transfer procedures to make azides, see: Raushel J, Pitram SM, Fokin VV. Org Lett. 2008;10:3385. doi: 10.1021/ol8011088.Goddard-Borger ED, Stick RV. Org Lett. 2007;9:3797. doi: 10.1021/ol701581g.Liu CY, Knochel P. J Org Chem. 2007;72:7106. doi: 10.1021/jo070774z.Barral K, Moorhouse AD, Moses JE. Org Lett. 2007;9:1809. doi: 10.1021/ol070527h.Das J, Patil SN, Awasthi R, Narasimhulu CP, Trehan S. Synthesis. 2005:1801.Liu Q, Tor Y. Org Lett. 2003;5:2571. doi: 10.1021/ol034919+.

- 10.For leading references, see: Moody CJ. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, Ley S, editors. Vol. 7. Pergamon; Oxford: 1991. pp. 21–38.Moody CJ. Stud Nat Prod Chem. 1988;1:163.Hemetsberger H, Knittel D, Weidmann H. Monatsh Chem. 1970;101:161.

- 11.(a) Söderberg BCG. Curr Org Chem. 2000;4:727. (review) [Google Scholar]; (b) Sundberg RJ, Russell HF, Ligon WV, Jr, Lin L-S. J Org Chem. 1972;37:719. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith PAS, Hall JH. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:480. [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith PAS, Brown BB. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:2435. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swenton JS, Ikeler TJ, Williams BH. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:3103. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks MG, Jones G. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1983:1277. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For example, see: Gritsan NP, Platz MS. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3844. doi: 10.1021/cr040055+.Murata S, Tsubone Y, Kawai R, Eguchi D, Tomioka H. J Phys Org Chem. 2005;18:9.Smith PAS, Hall JH. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:480.Smith PAS, Brown BB. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:2438.

- 15.Murata S, Yoshidome R, Satoh Y, Kato N, Tomioka H. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1428. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun K, Sachwani R, Richert KJ, Driver TG. Org Lett. 2009;11:3598. doi: 10.1021/ol901317j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abramovitch RA, Holcomb WD, Thompson WM, Wake S. J Org Chem. 1984;49:5124.Abramovitch RA, Kress AO, McManus SP, Smith MR. J Org Chem. 1984;49:3114.cf.Abramovitch RA, Holcomb WD, Wake S. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:1525.Abramovitch RA, Knaus GN, Stowe RW. J Org Chem. 1974;39:2513.

- 18.cf.Cipollone A, Loreto MA, Pellacani L, Tardella PA. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2584.Lindley JM, McRobbie IM, Meth-Cohn O, Suschitzky H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:4513.Shingaki T, Inagaki M, Takebayashi M, Lwowski W. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1972;45:3567.Lwowski W, Maricich TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:3630.

- 19.cf.Maslak P. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:8201.Breslow R, Herman F, Schwabacher AW. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:5359.Breslow R, Feiring A, Herman F. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:5937.

- 20.cf.Anastassiou AG, Simmons HE, Marsh FD. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:2296.Marsh FD, Hermes ME. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:4506.

- 21.cf.Breslow DS. In: Nitrenes. Lwowski W, editor. Wiley Interscience; New York: 1970. pp. 245–303.Sloan MF, Renfrow WB, Breslow DS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964;5:2905.Dermer OC, Edmison MT. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:70.Curtius T. Angew Chem. 1913;26:134.

- 22.cf.Abramovitch RA, Knaus GN, Uma V. J Org Chem. 1974;39:1101.Abramovitch RA, Bailey TD, Takaya T, Uma V. J Org Chem. 1974;39:340.

- 23.cf.Ando W, Ogino N, Migita T. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1971;44:2278.Ando W, Yagihara T, Kondo S, Nakayama K, Yamato H, Nakaido S, Migita T. J Org Chem. 1971;36:1732.

- 24.Bach T, Körber C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bach T, Körber C. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:1033. doi: 10.1021/jo991569p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bach T, Körber C. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2358. doi: 10.1021/jo991569p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacci JP, Greenman KL, Van Vranken DL. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4955. doi: 10.1021/jo0340410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami M, Uchida T, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:7071. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita H, Uchida T, Lrie R, Katsuki T. Chem Lett. 2007;36:1092. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami M, Uchida T, Saito B, Katsuki T. Chirality. 2003;15:116. doi: 10.1002/chir.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwart H, Khan AA. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:1951. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwart H, Khan AA. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:1950. [Google Scholar]

- 33.For a discussion of alternative mechanisms, see: Breslow DS. In: Nitrenes. Lwowski W, editor. Wiley Interscience; New York: 1970. pp. 245–303.

- 34.For reports of Pd-catalyzed N-atom transfer from azides, see: Migita T, Chiba T, Takahashi K, Saitoh N, Nakaido S, Kosugi M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1982;55:3943.Migita T, Hongoh K, Naka H, Nakaido S, Kosugi M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1988;61:931.Migita T, Chiba M, Kosugi M, Nakaido S. Chem Lett. 1978:1403.

- 35.Groves JT, Takahashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:2073. [Google Scholar]

- 36.For leading references, see Nishikori H, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:9245.Evans DA, Faul MM, Bilodeau MT. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2742.Li Z, Conser KR, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:5326.Evans DA, Faul MM, Bilodeau MT. J Org Chem. 1991;56:6744.Mansuy D, Mahy JP, Dureault A, Bedi G, Battioni P. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1984:1161.

- 37.Cenini S, Tollari S, Penoni A, Cereda C. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 1999;137:135. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caselli A, Gallo E, Fantauzzi S, Morlacchi S, Ragaini F, Cenini S. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2008:3009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.For mechanistic studies of related cobalt(II) porphyrin catalyzed asymmetric N-atom transfer reactions, see: Caselli A, Gallo E, Ragaini F, Ricatto F, Abbiati G, Cenini S. Inorg Chim Acta. 2006;359:2924.Caselli A, Gallo E, Ragaini F, Oppezzo A, Cenini S. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:2142.

- 40.Mueller P, Baud C, Naegeli I. J Phys Org Chem. 1998;11:597. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Omura K, Murakami M, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Chem Lett. 2003;32:354. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omura K, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Chem Commun. 2004:2060. doi: 10.1039/b407693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergmeier SC, Seth PP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:6181. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawabata H, Omura K, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:1571. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawabata H, Omura K, Uchida T, Katsuki T. Chem–Asian J. 2007;2:248. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukuyama T, Jow CK, Cheung M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:6373. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukuyama T, Cheung M, Jow CK, Hidai Y, Kan T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5831. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinreb SM, Demko DM, Lessen TA, Demers JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:2099. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinreb SM, Chase CE, Wipf P, Venkatraman S. Org Synth. 1998;75:161. [Google Scholar]

- 50.(a) Jones S, Selitsianos D. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3128. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brands KMJ, Jobson RB, Conrad KM, Williams JM, Pipik B, Cameron M, Davies AJ, Houghton PG, Ashwood MS, Cottrell IF, Reamer RA, Kennedy DJ, Dolling UH, Reider PJ. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4771. doi: 10.1021/jo011170c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao GY, Jones JE, Vyas R, Harden JD, Zhang XP. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6655. doi: 10.1021/jo0609226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones JE, Ruppel JV, Gao GY, Moore TM, Zhang XP. J Org Chem. 2008;73:7260. doi: 10.1021/jo801151x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Y, Fields KB, Zhang XP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14718. doi: 10.1021/ja044889l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruppel JV, Jones JE, Huff CA, Kamble RM, Chen Y, Zhang XP. Org Lett. 2008;10:1995. doi: 10.1021/ol800588p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Subbarayan V, Ruppel JV, Zhu S, Perman JA, Zhang XP. Chem Commun. 2009:4266. doi: 10.1039/b905727g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bach T, Schlummer B, Harms K. Chem Commun. 2000:287. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bach T, Schlummer B, Harms K. Chem–Eur J. 2001;7:2581. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010618)7:12<2581::aid-chem25810>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stokes BJ, Dong H, Leslie BE, Pumphrey AL, Driver TG. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7500. doi: 10.1021/ja072219k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong H, Shen M, Redford JE, Stokes BJ, Pumphrey AL, Driver TG. Org Lett. 2007;9:5191. doi: 10.1021/ol702262f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen M, Leslie BE, Driver TG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:5056. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsao ML, Gritsan N, James TR, Platz MS, Hrovat DA, Borden WT. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9343. doi: 10.1021/ja0351591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stokes BJ, Jovanović B, Dong H, Richert KJ, Riell RD, Driver TG, Driver G. J Org Chem. 2009;74:3225. doi: 10.1021/jo9002536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith PAS, Rowe CD, Hansen DW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5169. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stokes BJ, Richert KJ, Driver TG, Driver TG. J Org Chem. 2009;74:6442. doi: 10.1021/jo901224k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.For the derivation of σ+-constants, see Stock LM, Brown HC. Adv Phys Org Chem. 1963;1:35.Brown HC, Okamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:4979.Brown HC, Okamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:1913.

- 66.For leading examples, see: Moss RA, Ma Y, Sauers RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13968. doi: 10.1021/ja0207605.Swansburg S, Buncel E, Lemieux RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6594.Huang R, Espenson JH. J Org Chem. 1999;64:6374. doi: 10.1021/jo990967p.Fuchs R, Carlton DM. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:104.

- 67.Reviews: Frontier AJ, Collison C. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:7577.Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:6479.Tius MA. Eur J Org Chem. 2005:2193.Harmata M. Chemtracts. 2005;17:416.

- 68.(a) Yamataka H, Ammal SC, Asano T, Ohga Y. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2005;78:1851. [Google Scholar]; (b) Boyd DR, Jennings WB, Waring LC. J Org Chem. 1986;51:992. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roberts JD, Hall GE, Middleton WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:4778. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shou WG, Li J, Guo T, Lin Z, Jia G. Organometallics. 2009;28:6847. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cenini S, Gallo E, Penoni A, Ragaini F, Tollari S. Chem Commun. 2000:2265. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ragaini F, Penoni A, Gallo E, Tollari S, Gotti CL, Lapadula M, Mangioni E, Cenini S. Chem–Eur J. 2003;9:249. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fantauzzi S, Gallo E, Caselli A, Ragaini F, Casati N, Macchi P, Cenini S. Chem Commun. 2009:3952. doi: 10.1039/b903238j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.For related isolated ruthenium imido complexes, see: Au SM, Zhang SB, Fung WH, Yu WY, Che CM, Cheung KK. Chem Commun. 1998:2677.Au SM, Fung WF, Cheng MC, Che CM, Peng SM. Chem Commun. 1997:1655.Wong KY, Che CM, Li CK, Chiu WH, Zhou ZY, Mak TCW. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1992:754.

- 74.Ruppel JV, Kamble RM, Zhang XP. Org Lett. 2007;9:4889. doi: 10.1021/ol702265h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu H, Tao J, Jones JE, Wojtas L, Zhang XP. Org Lett. 2010;12:1248. doi: 10.1021/ol100110z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu H, Subbarayan V, Tao J, Zhang XP. Organometallics. 2010;29:389. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Espino CG, Wehn PM, Chow J, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6935. [Google Scholar]

- 78.For reports of methods to deprotect Troc-amines, see: Dong Q, Anderson CE, Ciufolini MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5681.Hancock G, Galopin IJ, Morgan BA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:249.Just G, Grozinger K. Synthesis. 1976:457.

- 79.Badiei YM, Dinescu A, Dai X, Palomino RM, Heinemann FW, Cundari TR, Warren TH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:9961. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dai X, Warren TH. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10085. doi: 10.1021/ja047935q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Badiei YM, Warren TH. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:5989. [Google Scholar]