Abstract

Low-income youth experience social-emotional problems linked to chronic stress that are exacerbated by lack of access to care. Drumming is a non-verbal, universal activity that builds upon a collectivistic aspect of diverse cultures and does not bear the stigma of therapy. A pretest-post-test non-equivalent control group design was used to assess the effects of 12 weeks of school counselor-led drumming on social-emotional behavior in two fifth-grade intervention classrooms versus two standard education control classrooms. The weekly intervention integrated rhythmic and group counseling activities to build skills, such as emotion management, focus and listening. The Teacher's Report Form was used to assess each of 101 participants (n = 54 experimental, n = 47 control, 90% Latino, 53.5% female, mean age 10.5 years, range 10–12 years). There was 100% retention. ANOVA testing showed that intervention classrooms improved significantly compared to the control group in broad-band scales (total problems (P < .01), internalizing problems (P < .02)), narrow-band syndrome scales (withdrawn/depression (P < .02), attention problems (P < .01), inattention subscale (P < .001)), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-oriented scales (anxiety problems (P < .01), attention deficit/hyperactivity problems (P < .01), inattention subscale (P < .001), oppositional defiant problems (P < .03)), and other scales (post-traumatic stress problems (P < .01), sluggish cognitive tempo (P < .001)). Participation in group drumming led to significant improvements in multiple domains of social-emotional behavior. This sustainable intervention can foster positive youth development and increase student-counselor interaction. These findings underscore the potential value of the arts as a therapeutic tool.

1. Introduction

Children under age 18 years represent a quarter of the total population of the USA (74 million) [1]; 39% are low-income, that is, living in families earning less than double the federal poverty level [2]. Although European Americans represent the largest number of low-income children (26%, 10.9 million), other groups are more disproportionately represented: Latino (61%, 9.4 million), African American (60%, 6.5 million), American Indian (57%, 0.3 million), Asian American (30%, 0.9 million), children of immigrant parents (58%, 7.4 million), children of native-born parents (35%, 20.2 million) [2].

1.1. Mental Health Needs of Low-Income Youth

Low-income youth are commonly exposed to stressors [3–12] that are well-established risk factors for behavior problems and school failure in the general youth population [13]. Correspondingly, socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with internalizing (e.g., depressive, anxious, somatizing, post-traumatic stress) and externalizing (e.g., antisocial, aggressive, delinquent, substance abusing) behavior in children and adolescents [3, 9, 14–22]. The burden of chronic stress held by low-income youth is compounded by poor access to health and mental health care [1, 22–26]. Moreover, low-income families may be reluctant to obtain services, for reasons ranging from stigma and attitude towards treatment [27, 28] to psychosocial and legal ramifications of reporting problems [12, 29, 30]. Minority youth, in particular, are at greater risk of encountering the “triple threat" of suboptimal health, lack of access to care and inferior services [26].

Notwithstanding, relatively few mental health interventions have targeted low-income youth, and most aim to reduce a single problem behavior or deficit [31–37] in contrast to a positive development approach of increasing core assets that may influence a range of problem behaviors [38, 39]. Positive youth development interventions facilitate positive outcomes through developmentally appropriate achievements intended to address the “whole child" [39].

1.2. Group Drumming for Positive Development, Cultural Relevance and Stress Reduction

Group drumming is a recreational music making activity that builds social-emotional assets consistent with a positive youth development approach. It is conducted in a circle and often led by a facilitator whose role is to maximize a sense of community through rhythmic dialogue. Group drumming is inclusive; it is non-verbal, universal, and does not require previous experience for participation. Furthermore, group drumming is culturally relevant; it is an integral part of diverse cultures, and supports the value of collectivism, shared by non-European-based cultures [40].

Previous studies of adults [41–43] and adolescents [44] have shown the biopsychosocial efficacy of group drumming, using protocols involving reflection and self-disclosure to reduce stress. These studies found neuroendocrine and immune changes that were indicative of reduced stress in normal adults with no previous experience in drumming [41], reduced burnout and improved mood in long-term care workers and nurses [42, 43], and improved social-emotional functioning in adolescents from a court-referred residential treatment center [44]. Other art forms used in therapeutic contexts with adults and children have also been linked with improvement in biopsychosocial indicators of stress [45–62].

The unique effectiveness of group drumming with reflection and self-disclosure [41], versus group drumming without these components, suggests the possible added benefit of integrating counseling activities with group drumming to reduce social and emotional manifestations of stress in low-income youth. Social–emotional skill building delivered in a framework of drumming may also confer benefits without the stigma of therapy.

1.3. Theoretical Rationale

According to Social Cognitive Theory, group drumming combined with group counseling activities would foster individual self-efficacy and positive outcome expectations through enactive attainment, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion and reduction of physiological arousal [63]. Furthermore, collective efficacy may grow through a shared sense of purpose [63]. In support of this notion, Paulo Freire's Empowerment Education Theory of Dialogue and Praxis asserts that the development of empathy through common experience enables more meaningful reflection and dialogue, which in turn sets the stage for action, or empowerment [64, 65].

1.4. Research Objective

In summary, low-income youth are in need of interventions to address social and emotional behavior linked to chronic stress. Therefore, could a school-based group drumming program, integrated with activities from group counseling, improve social and emotional behavior in low-income children?

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Population

Upon written approval by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Los Angeles, as well as the Program Evaluation and Research Branch of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), we utilized a pretest-post-test non-equivalent control group design to assess the effects of 12 weeks of school-counselor-led drumming, aimed at social and emotional skill building, on problem behavior in low-income fifth graders. Fifth graders were targeted for early intervention because they would be old enough to benefit from rhythm-based therapeutic activities involving reflection, and their peer-centric developmental stage would lend itself well to group activities [66]. The study was conducted in spring of 2007 at Napa Street Elementary School in the LAUSD. Students at the school were 89% Latino [67], of which ∼90% were US born [68], 75% were of Mexican ethnicity [68] and 66% were English learners [67]. Ninety-seven percent of the students in the school participated in the reduced-price lunch program, a statewide index of socioeconomic disadvantage [67].

2.2. Recruitment

Students from all four fifth-grade classes in the school were recruited for the study. Since there were two classes in each of two different academic scheduling tracks, one class from each track was assigned to the experimental condition, and the other class from each track was assigned to the standard education control condition. Assignment to treatment conditions was not randomized, due to school administrative constraints. The students were told that the study was being conducted to see how drumming might affect their experience in school. They were also told that one group would get weekly drumming for 12 weeks, while the other group would get two sessions after the end of the study.

Of 106 students, 101 obtained parental consent for participation (95%). In one case, non-participation was due to parent refusal. In four cases, consent forms were not returned, and parents could not be contacted. Students that did not have consent to participate went into the control classrooms during the intervention.

2.3. Demographics of Participants

Demographic characteristics of the four classes can be found in Table 1. Of 101 participants in the study, 47 (46.5%) were male and 54 (53.5%) were female. Ninety-one (90%) were Latino, five (5%) were African American, two (2%) were Filipino, two (2%) were European American and one (1%) was Asian; these percentages reflected the racial/ethnic demographics of the school [67]. The mean student age was 10.5 years (range 10–12 years). The 10 non-Latino students were spread across all four classrooms. In total, 54 students received the intervention and 47 students were in the standard education control group. There were no significant differences in the proportion of boys versus girls across the four classes. The two experimental group teachers were a European American male, age 43 years, and a Latina, age 33 years; the two control group teachers were European American females, ages 30 and 32 years. There was no loss of student or teacher participation in either the experimental or control groups.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the four classrooms.

| TE1 (n = 24) | TE2 (n = 22) | TE3 (n = 30) | TE4 (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | D | CN | D | CN |

| Sex | ||||

| Girls | 11 (45.8%) | 13 (59.1%) | 15 (50.0%) | 15 (60.0%) |

| Boys | 13 (54.2%) | 9 (40.9%) | 15 (50.0%) | 10 (40.0%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 10.58 (0.58) | 10.46 (0.67) | 10.43 (0.57) | 10.48 (0.51) |

| Race/ethnicity | 23 Latino | 21 Latino | 25 Latino | 22 Latino |

| 1 European American | 1 Asian | 3 African American | 2 African American | |

| 2 Filipino | 1 European American |

TE: teacher; D: drumming; CN: control.

2.4. Building Support from the School Community

Prior to the beginning of the study, all faculty and a few staff from Napa Street Elementary School attended a free in-service drumming workshop at Remo Recreational Music Center in North Hollywood, California. The purpose of this was to increase support for the pilot study from the overall faculty and, in particular, to increase compliance from those that would be involved in the study.

2.5. Assessment

The quantitative assessment instrument utilized was the Teacher's Report Form (TRF)—the teacher version of the Child Behavior Checklist—which yields a variety of scales of adaptive functioning derived from a mixed list of 120 factor-loaded items [69]. The TRF asks teachers to rate each of their students on problem behaviors over the past 2 months, with three possible response choices: 0 = not true (as far as you know), 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true. TRF scale scores have been standardized based on normative data from children 6–18 years of age, and the instrument has been subjected to extensive reliability and validity testing [69]. Use of the TRF has been reported in >1000 peer-reviewed publications [70] and its robustness has been demonstrated in multicultural settings as well [71].

The wide range of problem behavior scales offered by the TRF was advantageous, given that the study was exploratory in nature and intended to inform the focus of assessments in future research. The TRF yields three broad-band scales: Total Problems (an aggregate of all items on the rating form), Internalizing Problems (a composite of scores from three narrow-band syndrome scales: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints) and Externalizing Problems (a composite of scores from two narrow-band syndrome scales: Rule-Breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behavior). The TRF also derives three other narrow-band syndrome scales: Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems. In addition, it offers two subscales for the syndrome scale of Attention Problems: Inattention and Hyperactivity-Impulsivity. This set of empirically based scales constitutes the core of the TRF.

Items on the TRF can also be used to generate six scales that are consistent with categories from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), for the American Psychiatric Association [72]: Affective Problems, Anxiety Problems, Somatic Problems, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems, Oppositional Defiant Problems, and Conduct Problems. Furthermore, the TRF offers two subscales for the DSM-oriented scale of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems: Inattention and Hyperactivity-Impulsivity. Finally, four other scales can be scored using TRF items: Obsessive-Compulsive Problems, Post-traumatic Stress Problems, Sluggish Cognitive Tempo, and Positive Qualities.

Both experimental and control teachers completed a TRF for each student in her or his class within a 2-week window, immediately prior to the start of the study and immediately upon completion of the study. There was no missing data.

2.6. Protocol Development

The group drumming protocol was co-developed by a drum circle facilitator, a public health educator and the school counselor—a licensed clinical social worker familiar with the social, emotional and cultural needs of the research population. The intervention was solely administered by the school counselor and delivered to a whole classroom of students at a time, including the teacher—in order to foster indirect benefits to students through stress reduction, observational learning, and/or carryover of session themes to the classroom. Prior to delivering the intervention, the counselor attended a weekend training session on drum circle facilitation and practiced facilitating drum circles under supervision with five classrooms of students at two socioeconomically similar elementary schools in the LAUSD. This served to confirm the feasibility of working with a whole classroom of students at a time.

To control for the integrity of the rhythmic component of the intervention, the drum circle facilitator, who was experienced in working with children, served as a silent participant observer during the sessions and offered suggestions for improvement during debriefing meetings. A lesson plan was outlined in advance of each session based upon the previous one, and it was delivered with consistency to both classrooms designated to receive the intervention. Upon completion of the study, a scripted manual was developed for future research use.

2.7. Intervention

The intervention took place during the school day, right after lunch, for 40–45 min weekly, over a 12-week period. It consisted of a hybrid of activities used in contemporary drum circles and in group counseling with school-age pupils, to maximize development of social and emotional skills through guided interaction, reflection, and self-disclosure. Drums and rhythms were chosen to reflect cultural diversity; drumming activities emphasized process and not performance. Session themes included various combinations of positive behavior, team building, positive risk taking, self-esteem, awareness of others, leadership, sense of self, expressing feelings, managing anger, managing stress, empathy and gratitude. “Focus and listening" was a constant theme.

Each session began with the whole group playing an ongoing rhythm pattern to release stress, energize and establish a sense of community. Focus and listening was encouraged throughout the program via the use of non-verbal cues and “call and response"-type activities, which required the echoing back of an improvised rhythm played by a member of the group. Rhythmic activities were also used as the basis for lessons corresponding with session themes. For example, in the session on positive behavior, participants would simultaneously speak and beat the affirmation, “I am responsible, I do the right thing"; this was followed by a group discussion of the meaning of the affirmation for integration and internalization. In the session on sense of self and awareness of others, children shared their favorite color, food and animal while drumming to the syllables of the words. In the session on expressing feelings and managing anger, the group brainstormed ways to manage anger, learned a spoken “calm down mantra", and then expressed feelings on the drums. In the session on team building and positive risk taking, hand shakers were systematically passed around the circle in increasingly rapid succession until many dropped; this was followed by a discussion of the acceptability of making mistakes in the learning process and how it feels to give and receive. In the session on leadership, empathy and gratitude, when students were given an opportunity to lead a call and response from the center of the circle, other students were asked how the leader may have felt, which segued into a discussion of empathy and gratitude.

Session activities promoted the following constructs found in effective positive youth development programs: social-emotional-cognitive-behavioral-moral competence, self-efficacy, clear standards for behavior, healthy bonding, opportunities for prosocial involvement and recognition, structure and consistency in program delivery [38]. A more complete description of the group drumming protocol and its development will be published in a separate article.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

To examine group differences in the current sample, based on changes in scores from baseline to post-intervention/control, difference scores for the TRF scales were calculated by subtracting post-intervention/control scores from baseline scores for all scales. Preliminary analyses to examine the potential effect of the sex of the child on baseline TRF scores did not reveal any differences across the four classes. As the current investigation used a quasi-experimental design and did not randomly assign classrooms to study conditions, the drumming and control classes were not combined. Therefore, a series of ANOVAs were conducted to examine the effect of teacher (TE1 versus TE2 versus TE3 versus TE4) on each of the TRF scales separately. In the event of a significant omnibus F, Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc tests were conducted to specify which groups differed. The distributions of the TRF difference scores were examined to ensure that assumptions for parametric analyses were met. To normalize the distributions, outliers were identified and excluded for individual scales as detailed below. As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell [73], distributions of scores were examined within each classroom; values >2 SD from the mean were considered outliers. Effect sizes are reported in the form of partial eta squared (η p 2).

3. Results

3.1. TRF Broad-Band Scales

Baseline, post-intervention/ control, and difference scores for TRF broad-band scales that were statistically significant are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean (standard deviation) TRF broad-band scale scores by classroom.

| TE1 (n = 24) | TE2 (n = 22) | TE3 (n = 30) | TE4 (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | D | CN | D | CN |

| TRF scale | ||||

| Baseline TO | 7.6 (7.9) | 15.5 (11.3) | 10.7 (9.0) | 18.0 (14.6) |

| Post-TO | 3.6 (3.2) | 17.4 (11.1) | 7.4 (7.9) | 20.4 (14.0) |

| Difference TO | 4.0 (7.9) | –1.9 (7.4) | 3.3 (6.2) | –2.4 (7.6) |

| Baseline IP | 2.3 (3.1) | 3.4 (2.5) | 4.3 (4.8) | 4.4 (4.1) |

| Post-IP | 1.3 (1.4) | 4.3 (2.8) | 2.3 (2.2) | 4.1 (3.4) |

| Difference IP | 1.0 (3.2) | –0.9 (3.1) | 2.0 (3.5) | 0.3 (2.6) |

TE: teacher; D: drumming; CN: control; TRF: Teacher's Report Form; Difference: difference score (post-intervention/control minus baseline); TO: total problems; IP: internalizing problems. A positive value for difference scores indicates improvement whereas a negative value indicates worsening of symptoms.

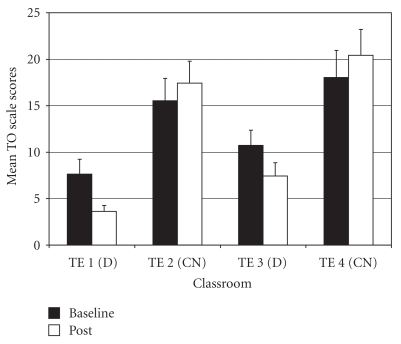

Total Problems (TO—an aggregate of all items on the rating form). For TO difference scores, there was an overall significant group difference (F(3,97) = 5.27, P < .01; η p 2 = 0.14). Post-hoc tests showed that drumming teacher TE1 rated students as improving more on TO scores than the two control teachers (TE2 and TE4) (Figure 1). Also, drumming teacher TE3 rated students as improving more on TO scores than control teacher TE4.

Figure 1.

Total problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

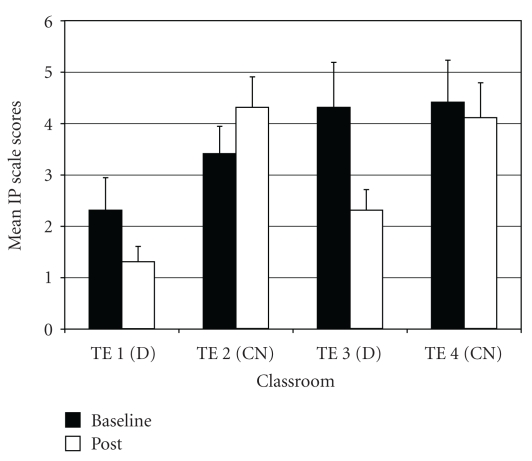

Internalizing Problems (IP—a composite of scores from three narrow-band syndrome scales: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints). For IP difference scores, the ANOVA showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,97) = 3.73, P < .02; η p 2 = 0.10). Post-hoc tests indicated that drumming teacher TE3 rated students as improving more on IP scores compared to control teacher TE2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Internalizing problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

Externalizing Problems (a composite of scores from two narrow-band syndrome scales: Rule-Breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behavior). Difference scores for externalizing problems were not significant between groups.

3.2. TRF Narrow-Band Syndrome Scales

Baseline, post-intervention/control and difference scores for TRF narrow-band syndrome scales that were statistically significant are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mean (standard deviation) TRF narrow-band syndrome scale scores by classroom.

| TE1 (n = 24) | TE2 (n = 22) | TE3 (n = 30) | TE4 (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | D | CN | D | CN |

| TRF scale | ||||

| Baseline WD | 0.6 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.9 (2.1) | 3.1 (3.0) |

| Post-WD | 0.1 (0.5) | 2.5 (2.1) | 1.1 (1.3) | 3.2 (2.6) |

| Difference WD | 0.5 (1.6) | –0.7 (2.4) | 0.8 (1.3) | –0.1 (1.6) |

| Baseline AP | 4.2 (4.6) | 9.7 (9.2) | 3.1 (4.6) | 9.1 (8.1) |

| Post-AP | 1.8 (2.3) | 10.8 (7.6) | 2.6 (4.1) | 10.6 (8.0) |

| Difference AP | 2.4 (4.0) | –1.1 (4.1) | 0.5 (2.3) | –1.5 (4.4) |

| Baseline IN | 3.2 (3.7) | 6.0 (5.5) | 1.5 (2.9) | 6.8 (7.1) |

| Post-IN | 1.0 (1.7) | 7.2 (4.9) | 0.8 (1.8) | 7.9 (6.5) |

| Difference IN | 2.2 (3.1) | –1.2 (3.3) | 0.7 (1.5) | –1.1 (3.7) |

TE: teacher; D: drumming; CN: control; TRF: Teacher's Report Form; Difference: difference score (post-intervention/control minus baseline); WD: withdrawn/depressed; AP: attention problems; IN: inattention (subscale of AP). A positive value for difference scores indicates improvement whereas a negative value indicates worsening of symptoms.

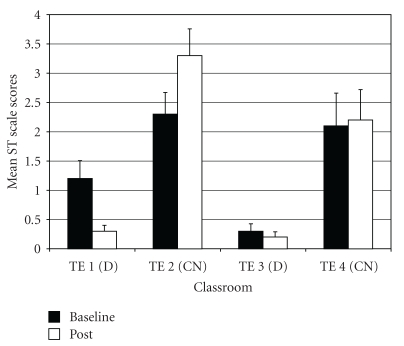

Withdrawn/Depressed (WD). For WD difference scores, two outliers were identified (both in drumming class 1). Exclusion of these outliers normalized the distribution. The ANOVA on WD difference scores showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,95) = 3.75, P < .02; η p 2 = 0.11). Post-hoc tests indicated that the two drumming teachers (TE1 and TE3) rated students as improving more on WD scores post-intervention compared to control teacher TE2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Withdrawn/depression—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

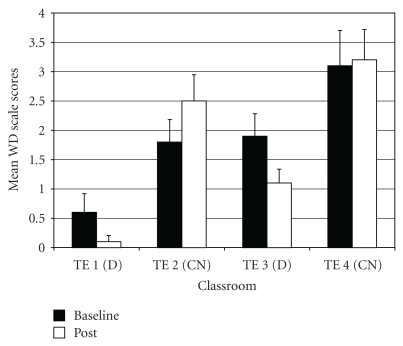

Attention Problems (AP). For AP difference scores, results of the ANOVA indicated a significant difference among groups (F(3,97) = 5.69, P < .01; η p 2 = 0.15). Post hoc tests showed that drumming teacher TE1 rated students as improving more on AP scores post-intervention relative to the two control teachers (TE2 and TE4) (Figure 4). In addition, drumming teacher TE3 rated students as improving more on AP scores compared to control teacher TE4.

Figure 4.

Attention problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

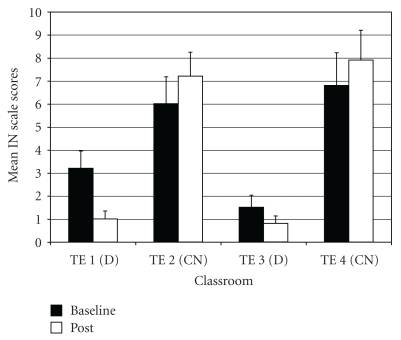

Inattention (IN—one of two subscales for Attention Problems; the other being Hyperactivity-Impulsivity). IN difference scores showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,97) = 7.16, P < .001; η p 2 = 0.18). Results of post-hoc tests indicated that the two drumming teachers (TE1 and TE3) rated students as improving more on IN scores post-intervention compared to the two control teachers (TE2 and TE4) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Inattention (subscale of attention problems)—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behavior, Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Subscale of Attention Problems. Difference scores for these syndrome scales were not significant between groups.

3.3. TRF DSM-Oriented Scales

Baseline, post-intervention/ control, and difference scores for TRF DSM-oriented scales that were statistically significant are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean (standard deviation) TRF DSM-oriented scale scores by classroom.

| TE1 (n = 24) | TE2 (n = 22) | TE3 (n = 30) | TE4 (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | D | CN | D | CN |

| TRF scale | ||||

| Baseline AN | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.7) |

| Post-AN | 0.04 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) |

| Difference AN | 0.46 (0.7) | –0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.8) | –0.1 (0.9) |

| Baseline AH | 2.5 (2.8) | 4.8 (4.7) | 1.9 (2.8) | 4.7 (4.5) |

| Post-AH | 1.1 (1.5) | 5.3 (4.3) | 1.5 (2.5) | 5.9 (4.8) |

| Difference AH | 1.4 (2.4) | –0.5 (1.9) | 0.4 (1.6) | –1.2 (2.9) |

| Baseline I | 1.7 (1.9) | 2.0 (2.1) | 0.5 (1.2) | 3.0 (3.3) |

| Post-I | 0.6 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.8) | 0.2 (0.6) | 3.6 (3.1) |

| Difference I | 1.1 (1.5) | –0.5 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.9) | –0.6 (1.8) |

| Baseline OD | 0.04 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.9 (2.0) | 0.6 (1.3) |

| Post OD | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.6) |

| Difference OD | –0.36 (0.2) | –0.1 (1.0) | 0.5 (1.2) | –0.3 (1.0) |

TE: teacher; D: drumming; CN: control; TRF: Teacher's Report Form; Difference: difference score (post-intervention/control minus baseline); AN: anxiety problems; AH: attention deficit/hyperactivity problems; I: inattention (subscale of AH); OD: oppositional defiant problems. A positive value for difference scores indicates improvement whereas a negative value indicates worsening of symptoms.

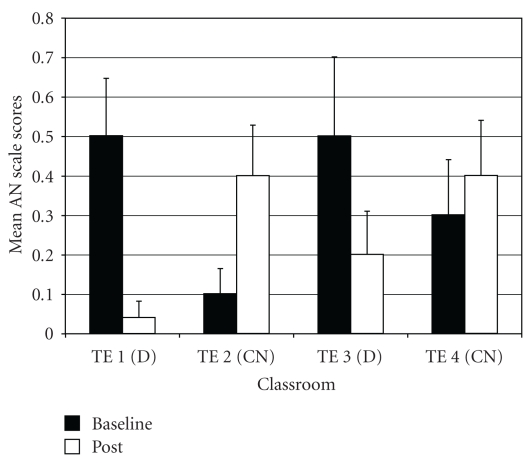

Anxiety Problems (AN). For AN difference scores, one outlier was identified (in drumming class 1); exclusion of this outlier normalized the distribution of AN scores. Results of the ANOVA on AN difference scores showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,96) = 4.97, P < .01; η p 2 = 0.15) Post-hoc tests indicated that the two drumming teachers (TE1 and TE3) rated students as improving more on AN scores post-intervention than control teacher TE2 (Figure 6). In addition, drumming teacher TE1 rated students as improving more on AN scores than control teacher TE4.

Figure 6.

Anxiety problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

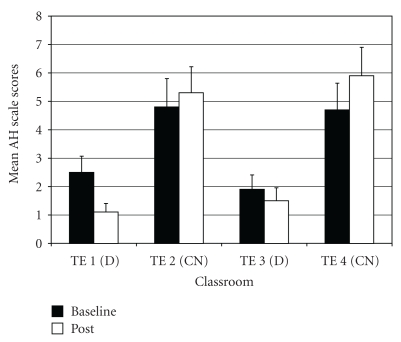

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems (AH). For AH difference scores, two outliers were identified (both in control class 4), and exclusion of these outliers normalized the distribution. The ANOVA on AH difference scores showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,95) = 5.96, P < .01; η p 2 = 0.14). Post-hoc tests indicated that drumming teacher TE1 rated students as improving more on AH scores compared to the two control teachers (TE2 and TE4) (Figure 7). In addition, drumming teacher TE3 rated students as improving more on AH scores relative to control teacher TE4.

Figure 7.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

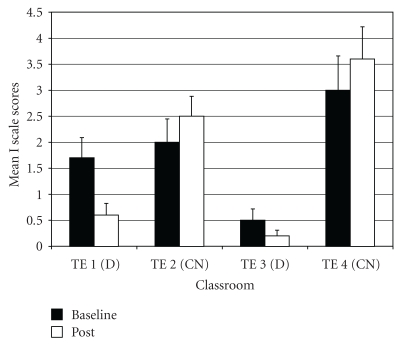

Inattention (I—one of two subscales for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems; the other being Hyperactivity-Impulsivity). For I difference scores, the ANOVA results showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,97) = 7.51, P < .001; η p 2 = 0.19). Post-hoc tests indicated that drumming teacher TE1 rated students as improving more on I scores than the two control teachers (TE2 and TE4) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Inattention (subscale of attention deficit/hyperactivity problems)—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

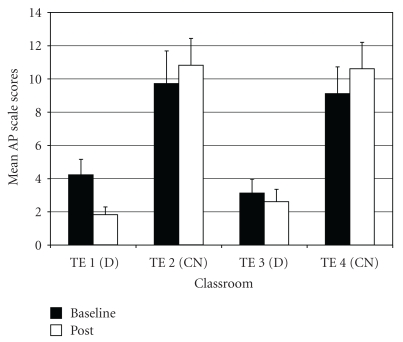

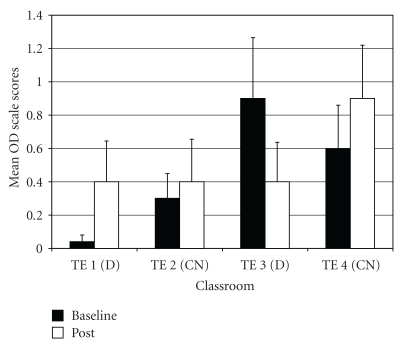

Oppositional Defiant Problems (OD). For OD difference scores, results of the ANOVA indicated a significant difference among groups (F(3,97) = 3.36, P < .03; η p 2 = 0.09). Post-hoc tests showed that drumming teacher TE3 rated students as improving more on OD scores than control teacher TE4 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Oppositional defiant problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

Affective Problems, Somatic Problems, Conduct Problems, Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Subscale of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems. Difference scores for these DSM-oriented scales were not significant between groups.

3.4. TRF Other Scales

Baseline, post-intervention/control, and difference scores for TRF other scales that were statistically significant are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean (standard deviation) TRF other scale scores by classroom.

| TE1 (n = 24) | TE2 (n = 22) | TE3 (n = 30) | TE4 (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | D | CN | D | CN |

| TRF Scale | ||||

| Baseline PT | 0.8 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.8 (2.1) | 2.9 (2.4) |

| Post- PT | 0.3 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.6 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.5) |

| Difference PT | 0.5 (1.6) | −0.9 (1.8) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.4 (1.8) |

| Baseline ST | 1.2 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.7) | 0.3 (0.7) | 2.1 (2.8) |

| Post-ST | 0.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (2.1) | 0.2 (0.5) | 2.2 (2.6) |

| Difference ST | 0.9 (1.4) | −1.0 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.3) | −0.1 (1.6) |

TE: teacher; D: drumming; CN: control; TRF: Teacher's Report Form; Difference: difference score (post-intervention/control minus baseline); PT: post-traumatic stress problems; ST: sluggish cognitive tempo. A positive value for difference scores indicates improvement whereas a negative value indicates worsening of symptoms.

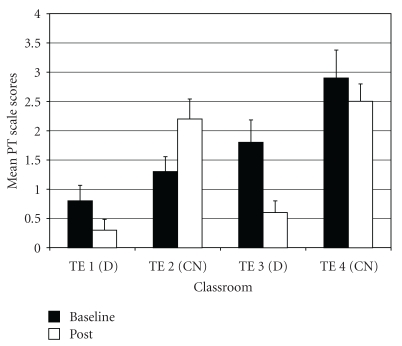

Post-Traumatic Stress Problems (PT). For PT difference scores, results of the ANOVA showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,97) = 6.40, P < .01; η p 2 = 0.17). Post-hoc tests indicated that drumming teachers TE1 and TE3 rated students as improving more on PT scores compared to control teacher TE2 (Figure 10). In addition, control teacher TE4 rated students as improving more on PT scores compared to the other control teacher TE2.

Figure 10.

Post-traumatic stress problems—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (ST). For ST difference scores, one outlier was identified (in control class 2). Exclusion of this outlier normalized the distribution. The ANOVA on ST difference scores showed a significant difference among groups (F(3,96) = 9.29, P < .001; η p 2 = 0.23). Post-hoc tests indicated that drumming teacher TE1 rated students as more improved on ST scores compared to the two control teachers (TE2 and TE4), as well as the other drumming teacher TE3 (Figure 11). Also, drumming teacher TE3 rated students as improving more on ST scores than control teacher TE2, and control teacher TE4 rated students as declining less on ST scores than the other control teacher TE2.

Figure 11.

Sluggish cognitive tempo—mean baseline and post-intervention/control scores by classroom.

Obsessive-Compulsive Problems, Positive Qualities. Difference scores for these other scales were not significant between groups.

4. Discussion

This pilot study investigated the impact of group drumming on social-emotional behavior in low-income, primarily Latino, children with the specific aim of identifying the range of behaviors that may show improvement with intervention. The TRF was utilized to assess a myriad of problem behaviors. Students in the school counselor-led drumming program improved significantly compared to the control group in multiple domains of social-emotional behavior. Significant changes were found in broad-band scales (total problems and internalizing problems), narrow-band syndrome scales (withdrawn/depression, attention problems, and inattention subscale), DSM-oriented scales (anxiety problems, attention deficit/hyperactivity problems, inattention subscale, and oppositional defiant problems), and other scales (post-traumatic stress problems and sluggish cognitive tempo). On each of these scales, at least one drumming class did better than at least one control class. These findings support our hypothesis that a school-based group drumming program, integrated with activities from group counseling, would improve social and emotional behavior in low-income children.

4.1. Implications

The results of this study suggest that group drumming combined with group counseling may be used effectively to mitigate internalizing problems in a low-income, predominantly Latino, population. This is important not only because Latino youth tend to report more internalizing problems than other youth [74–76], but also because these types of problems are even difficult for their caregivers [77] and physicians [17] to identify. In addition, children manifesting behavior problems in the attention spectrum (including sluggish cognitive tempo, which can be a proxy for inattention) [78] seem to respond well to this intervention.

The effectiveness of the intervention appears to have been due to the combination of drumming and counseling activities, based on surveys of the teacher participants and anecdotal reports by the school counselor, observer, and students involved in the study. In support of this assumption, Bittman et al. evaluated six different protocols (resting control, listening to drumming music, 50% instruction and 50% drumming activity, 20% instruction and 80% drumming activity, facilitated shamanic drumming, and composite drumming involving reflection and self-disclosure facilitated specifically by a music therapist) and found that only the composite protocol led to neuroendocrine and immune changes in adults, at a level indicative of stress reduction [41].

The strength of this intervention was reflected in its effectiveness within a realistic school context [79]. In the name of sustainability, a school counselor was used to deliver the intervention, rather than an expert drum circle facilitator. Moreover, an entire classroom of a mixed composition of up to 30 students was served at a time, despite the fact that a stronger effect may have been achieved by working with groups of 10–15 students at a time [41, 42, 80, 81] or by delivering it only to those screened for critical levels of need [82–86]. In addition, implementation took place during the school day after lunch, which is a difficult time of day to teach based upon an informal survey of elementary school teachers. Finally, study participants were in their spring semester of fifth grade—the most challenging time of year for the most potentially resistant group of elementary school students.

The findings of this study are consistent with other school-based, short-term, group interventions aimed at improving behavior in low-income youth [80–82, 85, 87, 88]. Enhancing school-based services can reduce barriers to mental health care [89, 90], as they are the primary source of such care for youth [90, 91]. School settings are ideally suited for preventive services, extended observation, and coordinated care [89]. School counselor-led group drumming, as conceived in this study, not only expands these possibilities in culturally relevant ways but also offers an additional area in which students can excel. The intrinsic value of drumming, and the opportunity to develop competence in it, may lead to continued participation [92], which may in itself be helpful given the social, emotional and academic benefits that have been linked to participation in music activities [93] and organized activities in general [94]. The National Education Association calls for the use of the arts as a “hook" to get the growing number of Latino students interested in school [95]. School counselor-led group drumming can not only serve as the “hook" but also close an opportunity gap that exists for low-income youth [96, 97].

4.2. Limitations

Several methodological issues in this pilot feasibility study need to be considered, and future studies should attempt to address these limitations. First, the effect sizes in the current study (η p 2 = 0.09–0.23) were small due to the sample size and inclusionary approach to recruitment; however, one cannot underestimate the practical value of a change in behavior of even one student in a classroom [84]. Smaller gains across a broader distribution of risk factors may also have larger public health value [86, 98], particularly given variations in behavioral responses to stress based on race, ethnicity, and gender [18, 99–101]. Furthermore, achieving an effect under challenging circumstances may increase the value of the finding [79]. The effect sizes reported in this study are comparable to those found in meta-analyses of other interventions reported in the literature [36, 86, 102, 103].

Second, random assignment of classrooms to treatment conditions was not feasible due to school administrative constraints; however, selection bias was probably minimized by the homogeneity of the study population. Third, teacher raters were not blinded to the group assignment of the students and, thus, may have been prone to reporting bias; this is a major limitation of the pilot study. Future studies should include cross-informant measures or utilize objective observers in order to corroborate findings. Fourth, the lack of an attention control group [104] and the necessary inclusion of a “gifted" class in the experimental group may have had unintended effects.

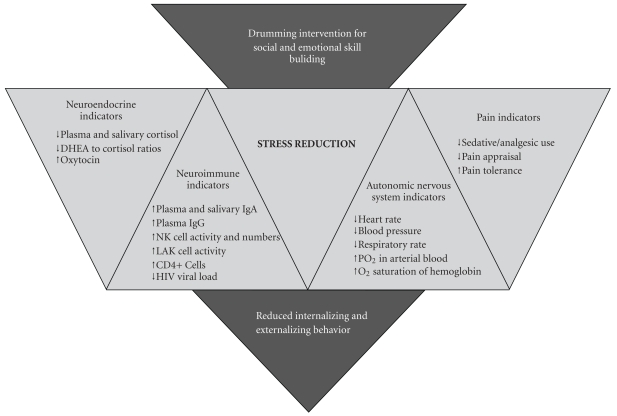

Finally, this study demonstrated that a group drumming intervention could improve social-emotional indicators of stress; however, in order to identify stress reduction more definitively as the possible mechanism, corresponding biological indicators should be measured. Figure 12 shows neuroendocrine, neuroimmune, autonomic nervous system, and pain indicators of stress reduction that have been associated with arts-based interventions in the scientific literature [41, 45–47, 49, 51–54, 56–58, 60].

Figure 12.

Stress reduction as the proposed mediator between the drumming intervention and reduced internalizing and externalizing behavior.

4.3. Future Research

The results of this study suggest that future investigations linking group drumming and social-emotional behavior in a low-income, primarily Latino, population should focus on assessment of problems in internalizing and attention spectrum domains. However, future studies should also involve larger samples, analyzed for effects on different subgroups of youth by race, ethnicity and gender, as differences in intervention effects have been reported in each of these areas [35, 80, 81, 86, 87]. In order to determine the integrity of results over time, follow up assessments would be necessary. It would also be useful to assess the extent to which a sustained or repeated intervention could mitigate behavior problems—such as substance abuse, gang involvement, and school dropout—that are not typically seen at the elementary school level. Additionally, while this study has demonstrated the effectiveness of group drumming for improving social-emotional behavior in a normative sample, future studies should assess its potential utility in a clinical population. The participants in this study were a non-referred population that showed baseline scores at or below the norm in all behavior scales; therefore, clinical significance cannot be inferred despite the statistically significant reductions in problem behaviors reflected in these scales [4, 9, 18, 69].

Future research should also investigate the effects of the group drumming intervention on academic performance [105, 106], particularly given a meta-analysis of 300+ studies that found academic achievement and behavior significantly improved by social-emotional learning [107]. The study reported here did not utilize the academic performance portion of the TRF, in an effort to reduce the burden on teacher respondents. Additionally, family participation may enhance the effects of the intervention, since family support has been shown to buffer internalizing and externalizing behavior in low-income youth [19, 21, 101, 108–111]. Group drumming lends itself well to family involvement, without the stigma of a mental health intervention [27, 28]. Finally, future studies should evaluate the relative efficacy of intervention delivery by other types of school personnel.

5. Conclusions

School counselor-led group drumming, integrated with activities from group counseling, appears to improve the social and emotional correlates of chronic stress in low-income children. Through a positive development approach, the program can increase core assets that may influence a wide spectrum of behaviors, thus yielding broad public health value. This sustainable program can increase student-counselor interaction, provide a feasible alternative to traditional counseling methods that may lose efficacy over time, and serve as a portal to mental health care for those with unmet needs. The results of this study underscore the potential value of the arts as a therapeutic tool.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following individuals who made this study possible: Mr Remo D. Belli, Dr Barry Bittman, Dr Jeffrey Gornbein, Ms Christine Stevens, Mr Mike DeMenno, Ms Karen Timko, Dr Petra Montante, Ms Ileana De Monte, Ms Giselle Friedman, Ms Olga Diaz, Ms Tina Gilmore, Ms Linda Gonzalez, Mr Rocky Sulka and the staff of Napa Street Elementary School.

References

- 1.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Census Bureau; 2008. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas-Hall A, Chau M. Basic Facts About Low-Income Children: Birth to Age 18. New York, NY, USA: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youngstrom E, Weist MD, Albus KE. Exploring violence exposure, stress, protective factors and behavioral problems among inner-city youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32(1-2):115–129. doi: 10.1023/a:1025607226122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veenema TG. Children’s exposure to community violence. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33(2):167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, García Coll C. The home environments of children in the United States part I: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Development. 2001;72(6):1844–1867. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dearing E, Taylor BA. Home improvements: within-family associations between income and the quality of children’s home environments. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28(5-6):427–444. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(2):179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC. Economic well-being and children's social adjustment: the role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development. 2002;73(3):935–951. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caplan S. Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: a dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice. 2007;8(2):93–106. doi: 10.1177/1527154407301751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan MM, Rehm R. Mental health of undocumented Mexican immigrants: a review of the literature. Advances in Nursing Science. 2005;28(3):240–251. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durlak JA. Common risk and protective factors in successful prevention programs. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):512–520. doi: 10.1037/h0080360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mcleod JD, Shanahan MJ. Trajectories of poverty and children’s mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37(3):207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eamon MK, Mulder C. Predicting antisocial behavior among Latino young adolescents: an ecological systems analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(1):117–127. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello EJ, Farmer EMZ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Erkanli A. Psychiatric disorders among American Indian and white youth in Appalachia: the great smoky mountains study. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(5):827–832. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarshis TP, Jutte DP, Huffman LC. Provider recognition of psychosocial problems in low-income Latino children. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(2):342–357. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant KE, Katz BN, Thomas KJ, et al. Psychological symptoms affecting low-income urban youth. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(6):613–634. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill HM, Madhere S. Exposure to community violence and African American children: a multidimensional model of risks and resources. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(1):26–43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loukas A, Prelow HM. Externalizing and internalizing problems in low-income Latino early adolescents: risk, resource, and protective factors. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(3):250–273. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hovey JD, King CA. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(9):1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadsworth ME, Achenbach TM. Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: testing two mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(6):1146–1153. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ku L, Waidmann T. How Race/Ethnicity, Immigration Status, and Language Affect Health Insurance Coverage, Access to Care and Quality of Care Among the Low Income Population. Washington, DC, USA: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zambrana RE, Logie LA. Latino child health: need for inclusion in the US national discourse. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(12):1827–1833. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avruch S, Machlin S, Bonin P, Ullman F. The demographic characteristics of Medicaid-eligible uninsured children. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(3):445–447. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):e286–e298. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ojeda VD, Bergstresser SM. Gender, race-ethnicity, and psychosocial barriers to mental health care: an examination of perceptions and attitudes among adults reporting unmet need. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49(3):317–334. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1547–1554. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis MJ, West B, Bautista L, Greenberg AM, Done-Perez I. Perceptions of service providers and community members on intimate partner violence within a Latino community. Health Education and Behavior. 2005;32(1):69–83. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3:151–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez MC, Morrobel D. A review of latino youth development research and a call for an asset orientation. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(2):107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weisz JR, Doss AJ, Hawley KM. Youth psychotherapy outcome research: a review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:337–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman WK, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):105–130. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merry S, McDowell H, Hetrick S, Bir J, Muller N. Psychological and/or educational interventions for the prevention of depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003380.pub2. Article ID CD003380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huey SJ, Jr., Polo AJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):262–301. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobler NS, Roona MR, Ochshorn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, Stackpole KM. School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;20(4):275–336. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy LA, Newman E, de Thomas CA, Chun V. Effectiveness of school-based prevention and intervention programs for children and adolescents with emotional disturbance: a meta-analysis. Journal of School Psychology. 2009;47(2):77–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JAM, Lonczak HS, Hawkins JD. Positive youth development in the United States: research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;591:98–124. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Berglund ML, Pollard JA, Arthur MW. Prevention science and positive youth development: competitive or cooperative frameworks? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(6):230–239. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Triandis HC. Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69(6):907–924. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bittman BB, Berk LS, Felten DL, et al. Composite effects of group drumming music therapy on modulation of neuroendocrine-immune parameters in normal subjects. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2001;7(1):38–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bittman BB, Bruhn KT, Stevens C, Westengard J, Umbach PO. Recreational music-making: a cost-effective group interdisciplinary strategy for reducing burnout and improving mood states in long-term care workers. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. 2003;19(3-4):4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bittman BB, Snyder C, Bruhn KT, et al. Recreational music-making: an integrative group intervention for reducing burnout and improving mood states in first year associate degree nursing students: insights and economic impact. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship. 2004;1(1, article 12) doi: 10.2202/1548-923x.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bittman BB, Dickson L, Coddington K. Creative musical expression as a catalyst for quality-of-life improvement in inner-city adolescents placed in a court-referred residential treatment program. Advances. 2009;24:8–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett MP, Lengacher C. Humor and laughter may influence health IV. humor and immune function. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(2):159–164. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berk LS, Felten DL, Tan SA, Bittman BB, Westengard J. Modulation of neuroimmune parameters during the eustress of humor-associated mirthful laughter. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2001;7(2):62–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuber M, Hilber SD, Mintzer LL, Castaneda M, Glover D, Zeltzer L. Laughter, humor and pain perception in children: a pilot study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(2):271–276. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi A-N, Lee MS, Lee J-S. Group music intervention reduces aggression and improves self-esteem in children with highly aggressive behavior: a pilot controlled trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;7(2):213–217. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilliard RE. Music therapy in hospice and palliative care: a review of the empirical data. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005;2(2):173–178. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pelletier CL. The effect of music on decreasing arousal due to stress: a meta-analysis. Journal of Music Therapy. 2004;41(3):192–214. doi: 10.1093/jmt/41.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E, Kwan Tse FY. Effect of music on depression levels and physiological responses in community-based older adults. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2009;18(4):285–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nilsson U. Soothing music can increase oxytocin levels during bed rest after open-heart surgery: randomised control trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(15):2153–2161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klassen JA, Liang Y, Tjosvold L, Klassen TP, Hartling L. Music for pain and anxiety in children undergoing medical procedures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8(2):117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nilsson U. The anxiety- and pain-reducing effects of music interventions: a systematic review. AORN Journal. 2008;87(4):780–807. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gold C, Voracek M, Wigram T. Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: a meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45(6):1054–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(6):823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smyth JM, Hockemeyer JR, Tulloch H. Expressive writing and post-traumatic stress disorder: effects on trauma symptoms, mood states, and cortisol reactivity. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(1):85–93. doi: 10.1348/135910707X250866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66(2):272–275. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116782.49850.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monti DA, Peterson C, Shakin Kunkel EJ, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(5):363–373. doi: 10.1002/pon.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walsh SM, Radcliffe RS, Castillo LC, Kumar AM, Broschard DM. A pilot study to test the effects of art-making classes for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34(1):p. 38. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E9-E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cruz RF, Sabers DL. Dance/movement therapy is more effective than previously reported. Art Psychotherapy. 1998;25:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: a review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(2):254–263. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallerstein N, Sanchez-Merki V, Dow L. Freirian praxis in health education and community organizing: a case study of an adolescent prevention program. In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick, NJ, USA: Rutgers University Press; 1997. pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, NY, USA: Seabury Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erikson EH. The Life Cycle Completed: A Review. New York, NY, USA: W.W. Norton; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 67.California Department of Education Policy and Evaluation Division. School Demographic Characteristics. 2007 Growth Academic Performance Index (API) Report. Sacramento, Calif, USA: California Department of Education; 2007. http://ayp.cde.ca.gov/reports/ACntRpt2007/2007GrthSchDem.aspx?allcds=19-647336018270. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Los Angeles Unified School District Planning, Assessment, and Research Division. Student National Origin Report: Napa Elementary—District 1. Los Angeles, Calif, USA: Los Angeles Unified School District; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-Informant Assessment. Burlington, Vt, USA: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berube RL, Achenbach TM. Bibliography of Published Studies Reporting Use of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) Burlington, Vt, USA: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rescorla LA, Achenbach TM, Ginzburg S, et al. Consistency of teacher-reported problems for students in 21 countries. School Psychology Review. 2007;36(1):91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 72.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. Washington, DC, USA: APA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th edition. Boston, Mass, USA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the Children’s Depression Inventory: a meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):578–588. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rew L, Thomas N, Horner SD, Resnick MD, Beuhring T. Correlates of recent suicide attempts in a triethnic group of adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33(4):361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alegría M, Canino G, Lai S, et al. Understanding caregivers’ help-seeking for Latino children’s mental health care use. Medical Care. 2004;42(5):447–455. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124248.64190.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Multicultural Supplement to the Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, Vt, USA: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prentice DA, Miller DT. When small effects are impressive. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cardemil EV, Reivich KJ, Beevers CG, Seligman MEP, James J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in low-income, minority children: two-year follow-up. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(2):313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cardemil EV, Reivich KJ, Seligman MEP. The prevention of depressive symptoms in low-income minority middle school students. Prevention & Treatment. 2002;5, article 8 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(5):603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fields SA, McNamara JR. The prevention of child and adolescent violence: a review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8(1):61–91. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lösel F, Beelmann A. Effects of child skills training in preventing antisocial behavior: a systematic review of randomized evaluations. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2003;587:84–109. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ginsburg GS, Drake KL. School-based treatment for anxious African-American adolescents: a controlled pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(7):768–775. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized latino immigrant children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, Epstein JA, Diaz T, Botvin EM. Effectiveness of culturally focused and generic skills training approaches to alcohol and drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: two-year follow-up results. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garrison EG, Roy IS, Azar V. Responding to the mental health needs of Latino children and families through school-based services. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19(2):199–219. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs. 1995;14(3):147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. The NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version 2.3 (DISC- 2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacobs JE, Vernon MK, Eccles J. Activity choices in middle childhood: the roles of gender, self-beliefs, and parents’ influence. In: Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, editors. Organized Activities as Contexts of Development. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- 93.O’Neill SA. Youth music engagement in diverse contexts. In: Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, editors. Organized Activities as Contexts of Development. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, Lord H. Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents. In: Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, editors. Organized Activities as Contexts of Development. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Verdugo R. A Report on the Status of Hispanics in Education: Overcoming a History of Neglect. Washington, DC, USA: National Education Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wimer C, Bouffard SM, Caronongan P, Dearing E, Simpkins S, Weiss H. What are Kids Getting Into These Days? Demographic Differences in Youth Out-of-School Time Participation. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Harvard Family Research Project; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keiper S, Sandene BA, Persky HR, Kuang M. The Nation's Report Card: Arts 2008—Music & Visual Arts (NCES 2009–488) Washington, DC, USA: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 98.McKinlay JB, Marceau LD. A tale of 3 tails. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(3):295–298. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schwab-Stone M, Chen C, Greenberger E, Silver D, Lichtman J, Voyce C. No safe Haven II: the effects of violence exposure on urban youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(4):359–367. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pastore DR, Fisher M, Friedman SB. Violence and mental health problems among urban high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;18:320–324. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O'Donnell L, O'Donnell C, Wardlaw DM, Stueve A. Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(1-2):37–49. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014317.20704.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, et al. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):156–183. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rooney BL, Murray DM. A meta-analysis of smoking prevention programs after adjustment for errors in the unit of analysis. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(1):48–64. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Flay BR, Collins LM. Historical review of school-based randomized trials for evaluating problem behavior prevention programs. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2005;599:115–146. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hoagwood KE, Olin SS, Kerker BD, Kratochwill TR, Crowe M, Saka N. Empirically based school interventions targeted at academic and mental health functioning. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2007;15(2):66–92. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Breslau N, Breslau J, Peterson E, et al. Change in teachers' ratings of attention problems and subsequent change in academic achievement: a prospective analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(1):159–166. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Durlak JA, Weissberg RP. A major meta-analysis of positive youth development programs. In: Proceedings of Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; August 2005; Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, Florsheim P. Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):436–457. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Smokowski PR, Bacallao ML. Acculturation, internalizing mental health symptoms, and self-esteem: cultural experiences of Latino adolescents in North Carolina. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;37(3):273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Grant KE, O’Koon JH, Davis TH, et al. Protective factors affecting low-income urban African American youth exposed to stress. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2000;20(4):388–417. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Zapert KM, Maton KI. A longitudinal study of stress-buffering effects for urban African-American male adolescent problem behaviors and mental health. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]