Abstract

Objectives

Very little is known about variation in prescription drug use and spending. We examine variation in outpatient prescription use and spending for diabetes and hyperlipidemia in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system and its association with quality measures for these conditions.

Study Design and Methods

We compared outpatient prescription use, spending and quality of care across 135 VA Medical Centers (VAMCs) in 2008, including 2.3 million patients dispensed lipid-lowering medications and 981,031 dispensed diabetes medications. We calculated VAMC-level cost/patient for these medications, proportion of patients on brand-name drugs, and Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) scores for hyperlipidemia (LDL<100mg/dl) and diabetes (HgA1c>9 or not measured) at each facility.

Results

The median cost/patient for lipid-lowering agents in 2008 was $49.60 and varied from $39.68 in the least expensive quartile of VAMCs to $69.57 in the most expensive (p<0.001). For diabetes agents, median cost/patient was $158.34 and varied from $123.34 in the least expensive quartile to $198.31 in the most expensive (p<0.001). The proportion of patients dispensed brand name oral drugs in these classes in VAMCs in the most expensive quartile was twice that in the lowest quartile (p<0.001). There was no correlation between VAMC-level prescription spending and performance on HEDIS measures for lipid-lowering drugs (r=.12 and r=.07) or diabetes agents (r=-.10).

Conclusions

Despite a closely managed formulary, significant variation in prescription spending and use of brand name drugs exists in the VA. Although we could not explicitly risk adjust, there appears to be no association between spending on medications and quality of care.

Introduction

Geographic variation in health care utilization and spending in the US is well-documented.1, 2 Researchers reported two-fold variation, for example, in Medicare spending in 2006 across hospital referral regions, after accounting for differences in prices and disease prevalence, due largely to differences in the volume of health care services delivered.3 Most studies to date have shown that areas with higher Medicare spending perform no better than low spending areas on process quality of care and health outcome measures and may, in fact, perform worse.4, 5 Areas of health care that exhibit a high degree of regional variation in use and spending tend to be those in which clinical evidence is relatively weak and there is a lack of consensus-based treatment guidelines.6

One area where spending has increased dramatically in the last 15 years is for prescription drugs.7 Despite the debate over the value of this increased spending,8 few studies have examined regional variation in prescription drug use.9-16 Most of these studies were conducted with data from the late 1990s, focused on variation within limited geographic regions, and/or did not examine the association between prescription drug spending and health outcomes.

We chose the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as the setting in which to study variation in outpatient prescription drug use and spending, and focus here on facility-level variation. In the VA, we can isolate differences in prescription use independent of health system factors known to affect use, such as insurance coverage for prescription drugs and formularies. In addition, variation in drug spending will not be due to differences in price, because acquisition costs for medications generally do not vary between regions in the VA. Our objectives for this research were: 1) to assess the level of variation in outpatient prescription use and spending in the VA for two widely used therapeutic categories: lipid-lowering drugs and diabetes medications, and 2) to determine if VA Medical Centers (VAMCs) that spent more per patient for these medications performed better on routinely-collected quality measures for hyperlipidemia and diabetes.

Methods

Setting and data sources

The VA system is the one of the largest integrated health care systems in the U.S., with over 8 million Veterans enrolled and over 5 million receiving care.17, 18 In fiscal year (FY) 2008, the VA spent $3.1 billion on outpatient pharmaceuticals. Between 1996 and 2009, the VA transitioned from a decentralized system of more than 170 individual drug formularies to a single VA National Formulary (VANF).19, 20 Providers have access to all FDA-approved medications but must request and provide justification for non-formulary drugs prior to their use.

The VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Services’ database contains all individual VA outpatient pharmacy transactions in the U.S. We used aggregate outpatient pharmacy data for fiscal year 2008 to study prescription use and spending at 135 VAMCs nationwide. The database includes aggregate VAMC-level data on the cost for each dispensed product (acquisition cost to the VA), the number of unique patients receiving prescriptions, and the number of prescriptions and dosage units dispensed. We also obtained VAMC-level quality measures from the VA Office of Quality and Performance (explained below).

Population and drugs studied

We aggregated total prescription spending for lipid-lowering and diabetes medications (including insulin) at the VAMC-level. Each VAMC may include several hospitals and community-based clinics (e.g., VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, in Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 4, includes three different hospitals or divisions). VISN 15 (Missouri, Kansas, parts of Illinois) aggregates the prescription spending of its 6 VAMCs into two groups rather than at the facility-level as measured in the other regions of the country. We maintained the designation of these two groups as VAMCs for the purposes of the analysis of variation in spending.

We chose to study lipid-lowering and diabetes medications, which are commonly used medications, available in both brand and generic form, and treat conditions with objectively-measured quality outcomes (Table 1). For lipid-lowering medications we excluded bile acid sequestrants because of the likelihood that these agents are used for conditions other than hyperlipidemia (e.g., cholestyramine for chronic diarrhea or pruritis). We also excluded niacin products, because the VA recommends the use of brand-name Niaspan (long-acting niacin) over “nutritional” generics, and these agents are used clinically primarily for HDL and triglyceride control rather than LDL control.

Table 1.

Prescription drugs included in the study sample.

| Diabetes Drugs (VA Classes HS501 and HS502) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Name | Number of Veterans who use in VA (FY2008) | Acquisition Cost per Unit ($) (FY2008) | Brand or Generic |

| Miglitol (Glyset) | 308 | $0.46 | Brand |

| Sitagliptin (Januvia) | 1,523 | 3.31 | Brand |

| Pioglitazone (Actos) | 38,030 | 2.72 | Brand |

| Rosiglitazone (Avandia) | 68,008 | 2.57 | Brand |

| Nateglinide (Starlix) | 271 | 0.72 | Brand |

| Repaglinide (Prandin) | 1,410 | 0.69 | Brand |

| Acarbose | 18,898 | 0.41 | Generic |

| Chlorpropamide | 183 | 0.12 | Generic |

| Tolazamide | 637 | 0.16 | Generic |

| Tolbutamide | 205 | 0.13 | Generic |

| Glimepiride | 2,653 | 0.12 | Generic |

| Glipizide | 276,297 | 0.03 | Generic |

| Glyburide | 246,505 | 0.04 | Generic |

| Glyburide/Metformin | 15,647 | 0.11 | Generic |

| Metformin | 562,541 | 0.05 | Generic |

| Insulin | 315,172 | * | Brand |

| Lipid-Lowering Drugs (VA Class CV350, excluding Bile Acids) | |||

| Number of Veterans who use in VA (FY2008) | Acquisition Cost per Unit ($) (FY2008) | Brand or Generic | |

| Atorvastatin (Lipitor) | 52,228 | $2.27 | Brand |

| Rosuvastatin (Crestor) | 136,451 | 0.99 | Brand |

| Ezetimibe (Zetia) | 54,594 | 1.60 | Brand |

| Ezetimibe/Simvastatin (Vytorin) | 57,257 | 1.20 | Brand |

| Fluvastatin (Lescol) | 21,118 | 1.25 | Brand |

| Lovastatin | 151,604 | 0.21 | Generic |

| Lovastatin/niacin (Advicor) | 118 | 0.65 | Brand |

| Pravastatin | 117,193 | 0.17 | Generic |

| Simvastatin | 1,834,299 | 0.08 | Generic |

| Gemfibrozil | 209,545 | 0.07 | Generic |

| Fenofibrate | 28,220 | 0.52 | Generic |

Insulin product ‘units’ include multiple doses, as opposed to the oral hypoglycemic medications listed in the table, for which one unit is typically one dose. Therefore we do not provide unit costs.

Notes: Table indicates those drugs included in our sample, their average cost across VAMCs, and whether they are brand or generic. VA formulary agents are bolded (note: number of users may not add to total users by class, since patients may use more than one agent). Combination metformin/rosiglitazone and metformin/sitaglipitin are not listed above since they each had 5 users across the VA in FY08, although they are included in the sample.

Outcome variables

Drug Spending

Our main drug spending variable was the cost/patient in FY2008 for lipid-lowering and diabetes medications. We divided the total amount spent by each VAMC for these medication classes (i.e. acquisition cost for all dispensed units/pills in the class) by the number of unique patients dispensed these medications. For example, if a VAMC dispensed 100,000 pills of simvastatin at an acquisition cost of $.08 per pill, then the total amount spent by that VAMC would be $8,000. Since VA acquisition cost varies little across VAMCs, and PBM data include only drug costs and not pharmacy labor, supply, or overhead costs, differences in spending among VAMCs should reflect differences in prescribing practices (e.g., type of medicine and intensity of use) rather than differences in drug price or labor costs.

Our primary interest was estimating the extent of variation in spending due to prescribing differences as opposed to differences in adherence, which would affect the number of prescriptions filled and thus total cost per patient. Thus, we also calculated a second VAMC-level spending variable: average cost per 30-day prescription. The average cost per prescription at a VAMC depends on what drugs are filled (i.e., medication choice), rather than on the total days of supply dispensed in the year. VAMCs using more expensive, brand name agents will have higher average cost per prescription than those facilities that use fewer brand name agents, regardless of whether patients miss certain doses during the year or are on one or two agents to control their disease. We compare our two spending measures and assume that if they are highly correlated that VAMC-level spending differences are not driven by differences in adherence.

Quality of Care

VA collects Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures at each facility using independent reviewers from the External Peer Review Program (EPRP) who examine cross-sectional random samples of medical records.21 We used facility-level HEDIS measures obtained from the VA Office of Quality and Performance (OQP) to measure quality of care for hyperlipidemia and diabetes.22 Lipid-lowering and diabetes therapy are associated with improvements in these intermediate measures.23-25 Evidence on the association between surrogate measures and outcomes such as mortality is mixed;26 however, these measures are currently accepted quality metrics and are used to evaluate the performance of physicians, institutions and health plans.

a) Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) <100mg/dl

Data is abstracted on the percent of patients age 18-75 with a diagnosis of diabetes, and patients with ischemic heart disease, who have had a full lipid panel during the past year and whose most recent LDL is <100.

b) Hemoglobin A1c (HgA1c) >9 or not measured (poor control) in the past year

EPRP abstracts data on the percent of patients age 18-75 with a diagnosis of diabetes having HgA1c of >9 or for whom A1c testing was not conducted. This measure is the most up to date clinical measure of diabetes control used and reported by OQP. For ease of comparison across the two conditions, we reverse scored the HgA1C measurements (1-HEDIS score), so that a higher score represented better quality of care.

Independent variables

We expected drug spending to be associated with the level of brand name drug use. For lipid-lowering agents, we measured the percent of patients on lipid-lowering therapy at each facility receiving brand name drugs. We classified rosuvastatin (Crestor), atorvastatin (Lipitor), Fluvastatin (Lescol) and ezetimibe (Zetia/Vytorin), which are non-formulary in the VA, as brand name agents and examined variation in prescribing of these agents. For diabetes medications we measured the percent of patients on diabetes medication who received thiazolidinediones (i.e., Actos, Avandia), which are a brand-only class of oral hypoglycemics.

To examine whether patient-level and facility-level differences might explain the variation, we obtained facility-level data on organization characteristics from VA administrative sources, such as the percent of patients over age 65, the total number of outpatient visits, and the percent of uninsured patients seen as outpatients at each VAMC in 2008. In addition, we stratified facilities by “complexity” rating (complexity level of 1a or 1b on the VA Allocation Resource Center complexity scale). The VA rates each VAMC on this 5-level scale, with high complexity facilities seeing the largest volume of patients and having the highest patient risk. Patient risk is based on all VA patient diagnoses and uses the same Diagnostic Cost Group (DxCG) risk scores found in Medicare. In addition, high complexity facilities employ a higher relative number and breadth of specialists, offer the highest level of ICU care (based on type of services provided and availability of subspecialty services), train more medical residents, and engage in more research activities. These variables are combined in a weighted average using established methodology to create these ratings.27 More complex VAMCs have been shown to be more likely to have year-round emergency room access, academic physicians, formal residency training in primary care, local clinical champions and designated nurses for quality improvement.28 Facility characteristics included in the VA complexity ratings have previously been used to measure facility complexity in VA research.29

Statistical Analysis

We categorized VAMCs into spending quartiles and used Kruskal-Wallis tests to assess differences in the median cost per patient across each quartile for lipid-lowering and diabetes agents. We also used Kruskal-Wallis and chi square tests to assess differences in VAMC characteristics across quartiles. We used analysis of variance to test for differences in the mean proportion of patients using brand name non-formulary drugs across the quartiles. We used spearman correlation coefficients and scatter plots to examine the relationship between cost per patient for lipid-lowering and diabetes agents at each VAMC. We also used spearman correlation coefficients and scatter plots to compare spending at each VAMC for lipid-lowering and diabetes agents with HEDIS quality scores for hyperlipidemia and diabetes, respectively.

To better characterize the independent effect of facility-level cost/patient on quality outcomes, we used logistic regression to model the probability of being in the highest quartile of quality for lipid-lowering and diabetes medications separately. Our primary independent variable was the cost/patient at the VAMC-level used as a continuous measure, and we included all facility characteristics described above as additional covariates in the analysis. We used SAS Version 9.2 for all analyses.

Results

Overall, 135 VAMCs were included in the analysis, representing 2.3 million Veterans dispensed lipid-lowering medication and 981,031 dispensed diabetes medications in FY08. Table 1 lists each of the medications studied, along with the number of unique pharmacy users, the medications’ average unit acquisition cost, and whether they are brand or generic medications. Generic agents were available at 10-20% of the acquisition cost of brand name drugs, on average.

Table 2 lists additional characteristics of the VAMCs, overall and by quartile of drug spending. For lipid-lowering agents, VAMCs in the most expensive quartiles had slightly fewer outpatient visits and Veterans on the medications (p>.05), but the proportion of patients age 65 and over was the same as in the less expensive quartiles. For the diabetes analysis, VAMCs in the most expensive quartile had a lower proportion of patients using insulin compared to VAMCs in the least expensive quartile (p=0.049) and a lower proportion of patients overall on diabetes medications (19.8% vs. 21.1%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.38).

Table 2.

Characteristics of VAMCs and spending and use outcome measures (shaded) for fiscal year 2008 overall and by quartile of spending.

| Quartiles of Spending | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | (1) Lowest | (2) | (3) | (4) Highest | |

| Lipid-Lowering Agents | |||||

| Percent of Veterans 65+ a | 46.8 | 46.0 | 47.9 | 46.7 | 46.5 |

| Number of outpatient visits a | 364,398 | 401,474 | 360,687 | 391,816 | 347,159 |

| Percent of Veterans without insurance | 42.6 | 41.8 | 39.7 | 44.8 | 44.9 |

| Number of Veterans on lipid-lowering agents | 15,656 | 18,244 | 15,018 | 16,703 | 14,377 |

| Percent of Veterans on lipid-lowering agentsb | 49.8 | 51.6 | 49.7 | 49.4 | 50.8 |

| Percent high complexity VAMCs(1a or 1b)c | 35.6 | 46.9 | 22.86 | 38.2 | 35.3 |

| Cost/Patient ($) ** | 49.60 | 39.68 | 47.31 | 55.76 | 69.57 |

| Cost/30-Day Prescription ($) ** | 5.22 | 4.06 | 4.86 | 5.68 | 7.12 |

| Brand-name agents (mean % of patients)** | 11.4 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 12.7 | 15.5 |

| Diabetes Agents | |||||

| Percent of Veterans 65+a | 46.8 | 45.5 | 46.8 | 49.0 | 45.5 |

| Number of outpatient visits a | 364,398 | 415,791 | 337,061 | 335,692 | 362,845 |

| Percent of Veterans without insurance | 42.6 | 44.8 | 40.2 | 43.1 | 43.6 |

| Number of Veterans on diabetes agents | 6,540 | 6,961 | 6,466 | 6,352 | 6,352 |

| Percent of Veterans on diabetes agentsb | 20.5 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 19.8 |

| Percent of Veterans on diabetes agents using who use Insulin* | 32.9 | 33.3 | 34.1 | 32.8 | 31.0 |

| Percent high complexity VAMCs(1a or 1b)c | 35.6 | 45.5 | 29.4 | 38.2 | 29.4 |

| Cost/Patient ($) ** | 158.34 | 123.34 | 146.47 | 172.53 | 198.31 |

| Cost/30-Day Prescription ($) ** | 10.65 | 8.67 | 9.83 | 11.47 | 13.24 |

| Thiazolidinedione use (mean % of patients) ** | 9.0 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 13.0 |

N= 135. Note that spending quartiles are calculated separately for each class. All values are median VAMC values, unless otherwise noted (e.g. number of outpatient visits is the median number of outpatient visits at VAMCs, for the overall sample of 135 VAMCs and for VAMCs in each quartile.)

The denominator is all Veterans enrolled in the VAMC.

The denominator is all Veterans filling at least 1 prescription of any kind

The percent of all VAMCs in the sample that are rated 1a or 1b on the VA complexity scale

p<.05 for overall difference across the quartiles

p <.001 for overall difference across the quartiles

For patients on lipid-lowering agents in FY08, the median cost per patient per year was $49.60 (IQR $42.80 to $61.00) and ranged from $23.50 to $125.00. VAMCs in the most expensive quartile had a median cost per patient of $69.57, which was 75% higher than VAMCs in the least expensive quartile ($39.68) (Table 2). The median cost per patient per year for diabetes agents was $158.34 (IQR $136.23 to $182.13) and ranged across VAMCs from $106.95 to a high of $306.58. VAMCs in the most expensive quartile had median costs per patient of $198.31, 60% higher than VAMCs in the least expensive quartile ($123.34). Calculations using cost per 30-day prescription showed similar levels of variation, and the two measures were highly correlated (r>0.95). The percentage of patients on brand name oral medications was highest in the VAMCs with the highest prescription spending for both lipid-lowering and diabetes medications (p<0.001), with percentages in the highest quartile more than twice that in the lowest quartile for lipid-lowering drugs and almost twice the percentage for oral diabetes medications(Table 2).

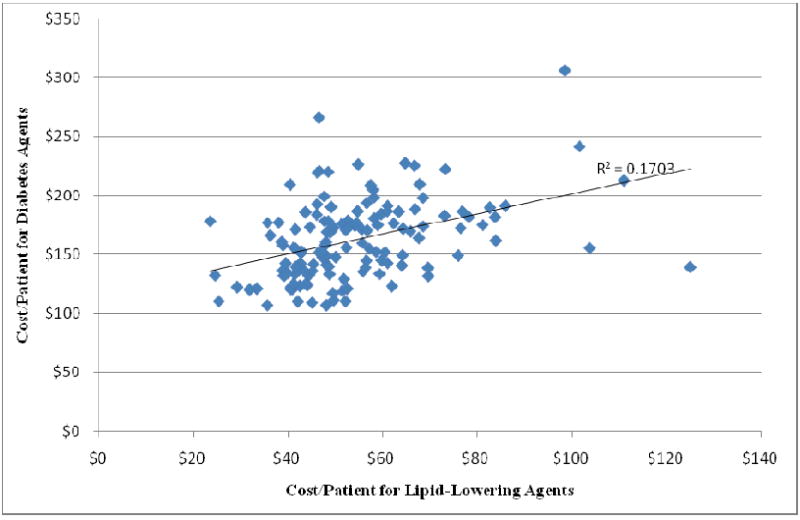

There was a moderate correlation between VAMC-level cost/patient for lipid-lowering drugs and cost/patient for diabetes agents (r=0.41, p<.001) (Figure 1). Nearly half (47.1%) of VAMCs in the highest quartile for lipid-lowering drugs were also in the highest quartile for diabetes drugs (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Relationship between cost/patient for lipid-lowering and diabetes agents. Each data point represents one VAMC (r=0.41, p <.001).

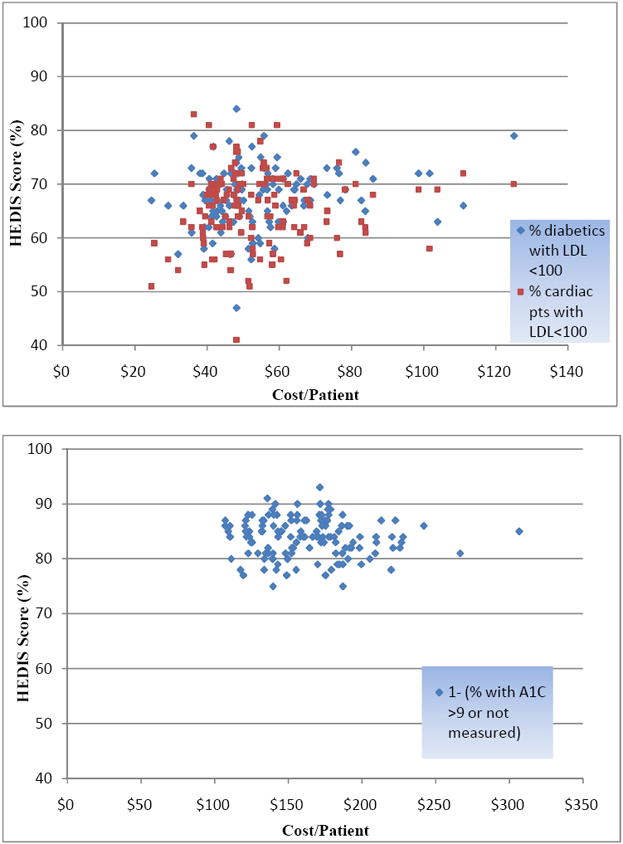

There was no statistically significant relationship between average prescription spending and performance on disease-specific HEDIS scores across VAMCs for lipid-lowering drugs (r=0.12, p=0.16 for diabetics with LDL <100; r=0.07, p=0.42 for heart disease patients with LDL<100) and diabetes agents (r= -0.10, p=0.27 for diabetics with A1C>9) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The cost/patient for lipid-lowering (top) and diabetes (bottom) agents for FY 2008 in VAMCs and HEDIS quality of care measurements at each facility. Each dot represents one VAMC. For lipid-lowering agents, two separate HEDIS measures are included, represented by different shaded dots

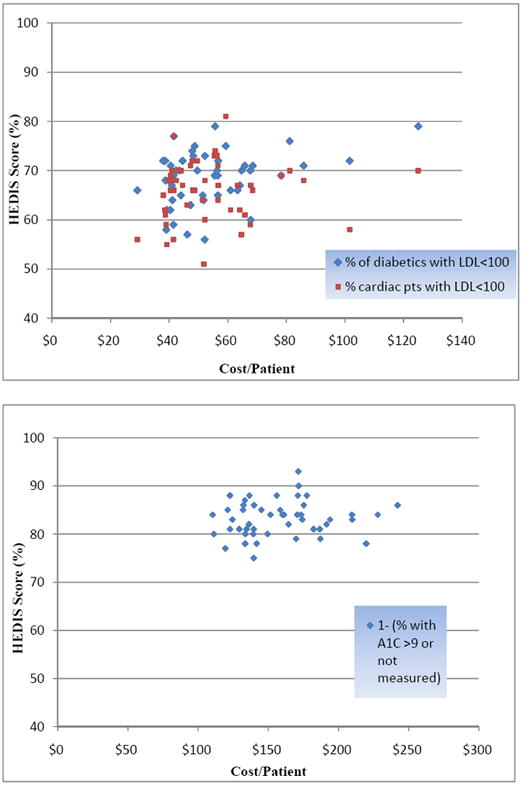

When we limited the analysis to VAMCs rated as high complexity facilities, the correlation between spending and quality approached statistical significance for lipid-lowering drugs, although it remained weak (r=0.28, p=0.06 for diabetics with LDL <100; r=0.12, p=0.40 for heart disease patients with LDL<100). There remained no relationship between spending and performance for diabetes measures (r=0.10, p=0.49 for A1c>9) (Figure 3). A similar lack of correlation was found between cost per 30-day prescription and quality of care (data not shown).

Figure 3.

The cost/patient for lipid-lowering (top) and diabetes (bottom) agents for FY 2008 in VAMCs and HEDIS quality of care measurements at each facility, limited to facilities rated as complexity level 1a or 1b (high complexity).

In logistic regression models controlling for facility characteristics (displayed in table 2), there remained no relationship between prescription spending and being in the highest quartile of quality for lipid-lowering (OR=1.02, 95% CI 0.99, 1.04, p=0.19 for diabetics with LDL <100; OR=1.01, 95% CI 0.99, 1.04, p=0.27 for heart disease patients with LDL <100) or diabetes drugs (OR=1.00 95% CI 0.98, 1.01, p=0.61). Full results from the multivariate regression are included in appendix table 1.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first national study of variation in outpatient prescription spending among adults in the VA, and the first study to assess variation of this kind in a large nationwide sample. We found widespread variation in yearly drug spending for two commonly used categories of prescription drugs. This variation in outpatient prescription spending and use exists in the VA despite a closely-managed formulary with uniform drug prices, a commitment to a uniform prescription benefit, and clinical guidance for the appropriate use of non-formulary medications.20 Moreover, VAMCs with higher spending per patient for these medication classes performed no better on quality measures.

Our findings on variation in VA prescribing are relatively consistent with prior studies in the VA system that addressed variation in outpatient prescribing, although previous studies were limited to small segments of the VA or examined variation only across VISNs.12, 14, 15 Gao and Campbell used 2003 VA data to look at trends in prescription costs and touched briefly on regional variation in prescription spending, although they did not separate inpatient and outpatient spending and did not assess the relationship between spending and quality.13 In the only other study we are aware of examining facility-level variation in outpatient prescription use in the entire VA, Aspinall et al. reported regional variation in rates of antibiotic prescribing for Veterans with upper-respiratory infections.9 Health outcomes associated with medication treatment were not examined.

Variation in prescription drug spending within the VA cannot be attributed to differences in prices paid for drugs. Prices (i.e., unit costs) are generally negotiated at the national level and vary only slightly across VAMCs, unlike prescription prices outside of the VA which vary markedly across institutions and classes of payer (e.g., uninsured, Medicaid, private insurer).30-32 Prescription prices can also vary over short time intervals, even days, in the private sector and true prices are difficult to obtain because of undisclosed manufacturer rebates, which would affect the measurement of prescription spending variation outside the VA.

Nor can these differences in use and spending be attributed to differences in VAMC formularies. We found significant differences across VAMCs in the use of brand-name non-formulary agents despite the presence of a national formulary and guidance for the use of non-formulary drugs. One explanation for this variation may be that although the formulary is the same across the VA, the procedures for adjudicating non-formulary requests (the process by which providers ask to use non-formulary agents) may vary by VAMC. We found that VA facilities that spent more per patient for one drug class were more likely to spend more on the other class as well. The VA may consider disseminating throughout the system best practices in formulary management from VAMCs with low pharmacy costs who perform well on quality of care measures.

Patient-level factors could explain variation in prescribing if patients at certain facilities are more or less likely to require non-formulary medications, either because of more severe comorbid illness or differences in risk of side-effects. When we repeated our analysis using only VAMCs with the highest complexity rating, our results were similar; however, our use of aggregate data means we cannot control for individual-level factors that might affect the need for more expensive agents. Differences in facility characteristics across quartiles of spending do not seem large enough to explain the level of variation we observed. In fact, the lower percentage of patients using insulin at VAMCs in the most expensive quartile argues against the idea that sicker patients are leading to higher costs at these VAMCs. In addition, regression analyses adjusting for facility level factors did not change the relationship, or lack thereof, between spending and quality.

Provider prescribing patterns differ by specialty, practice setting, level of training, age, and academic affiliation and these factors could explain some of the documented variation. Studies show that much of the variation in medication choice and choice of generic vs. brand name drugs is related to unobserved physician factors.33 It is unclear to what extent pharmaceutical promotion to physicians, for example, influences the prescribing behavior of VA physicians. VA ethics rules prohibit acceptance of significant gifts from the pharmaceutical industry and generally VAs do not accept free samples, although there is variation across VAMCs in the level of access to pharmaceutical sales representatives. Of note, VA has no authority to limit interactions with industry representatives for those providers who have dual affiliations with non-VA organizations.

In addition, because of the fluid way in which VA providers cross in and out of the VA system, especially in academic centers, local area practice patterns (the same ones that affect private practice physicians) may affect VA physicians.34 VA physicians may, in fact, prescribe similarly to non-VA physicians in the same region. Additionally, some VA patients bring prescriptions from private physicians to the VA and ask VA providers to “re-prescribe” them, suggesting that the effect of local area practice patterns on patients may be as important to the VA as the effect on providers.

Our work has important limitations. Our data are aggregated at the facility-level, and, as discussed above, we cannot risk adjust each facility’s prescription use to understand how differences in patient or provider factors may affect facility-level variation. In addition, there can be legitimate reasons why patients require brand name drugs in the VA, and our data do not allow us to focus on the appropriateness of use. Second, we cannot account for non-VA prescription use in our analysis, although we believe that Veterans who fill prescriptions in the VA (and thus are included in our sample) often do so because of the lower copay for these medications and thus would be unlikely to fill the same prescriptions outside the VA. There are some Veterans who fill prescriptions outside the VA using the $4 generic programs from large pharmacy retailers; the VA does not, however, have data on use of these programs by Veterans. We believe the overall impact of these low-cost generics for Veterans who are filling prescriptions in the VA was likely small in FY 2008. Third, variation in spending across VAMCs might be related to differences in patient refill adherence. Given that the degree of variation in cost per patient was similar to cost per prescription, we are confident that differences in adherence are not driving our findings. Fourth, we believe that HEDIS measures for diabetes and hyperlipidemia are important facility-level measures of quality of care and thus use them in our analysis; however, there are factors aside from prescription use that would affect these quality scores and the use of two quality measures may not adequately assess overall quality of care for patients with diabetes or hyperlipidemia.

Conclusion

The VA system has been successful in providing high quality care to Veterans35-37 while maintaining low rates of growth in prescription spending.38 Yet, substantial variation remains in prescription drug spending across medical centers in the VA. Understanding the causal mechanisms underlying this variation can help target prescription quality improvement programs. Our findings also have important implications for prescription drug spending outside the VA, where use of closed formularies is much less common, rates of generic drug use are lower, and variation may be even greater in magnitude and overall cost implications even more profound.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This material is the result of work supported with resources from the Pittsburgh VA Medical Center. Dr. Donohue was supported by Grant Number KL2 RR024154 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Appendix Table 1.

Results from multivariate logistic regression modeling the probability of being in the highest quartile of quality for lipid management (two measures) and diabetes.

| Lipid-Lowering Agents | Diabetes Agents | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | % of patients with diabetes with LDl <100 | % of patients with heart disease with LDL<100 | % of patients with A1c in poor control | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Cost/Patient | 1.02 | 0.99-1.04 | .19 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.04 | .27 | 1.00 | 0.98-1.01 | .61 |

| Percent 65+ | 1.04 | 0.97-1.12 | .31 | 1.10 | 1.03-1.18 | .008 | 1.08 | 1.01-1.16 | .04 |

| Number of outpatient visits | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | .04 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | .63 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | .41 |

| Percent without insurance | 0.29 | 0.003-33.29 | .62 | 1.53 | 0.03-92.58 | .84 | 0.81 | 0.01-56.72 | .92 |

| High Complexity VAMC | 5.73 | 1.54-21.25 | .009 | 1.22 | 0.38-3.92 | .74 | 0.75 | 0.23-2.39 | .62 |

| Percent on lipid-lowering agents | 1.03 | 0.94-1.13 | .54 | 1.00 | 0.91-1.09 | .93 | |||

| Percent on diabetes agents | 0.99 | 0.86-1.15 | .92 | ||||||

| Percent using Insulin | 1.10 | 0.97-1.24 | .16 | ||||||

Notes: Unit of analysis is the VAMC. High Complexity VAMC is a dichotomous variable to indicate whether or not each VAMC is a high complexity facility. All other variables are used as continuous measures. C statistic is 0.692, 0.679, 0.680 for each of the logistic models (from left to right).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: “This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.”

Contributor Information

Walid F. Gellad, Core Investigator, VA Pittsburgh Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Associate Scientist, RAND Corporation.

Chester B. Good, Chair, VA PBM Strategic Healthcare Group Medical Advisory Panel, Co-Director, VA Center for Medication Safety, Professor of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

John C. Lowe, Associate Chief Consultant, Veterans Health Administration Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Assistant Professor of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh.

Julie M. Donohue, Assistant Professor of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

References

- 1.Wennberg JE, Cooper MM. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United States. Chicago: AHA Press: Dartmouth Medical School. Center for Evaluative Clinical Sciences; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gawande A. The cost conundrum: What a Texas town can teach us about health care. The New Yorker. 2009 June;1:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Care Spending, Quality, and Outcomes: More Isn’t Always Better. [March 25, 2009];The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. 2009 February 27; 2009, at http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/atlases/Spending_Brief_022709.pdf. [PubMed]

- 4.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EtL. The Implications of Regional Variations in Medicare Spending. Part 2: Health Outcomes and Satisfaction with Care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasaitis L, Fisher ES, Skinner JS, Chandra A. Hospital Quality And Intensity Of Spending: Is There An Association? Health Aff. 2009;28:w566–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirovich B, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary Decision Making By Primary Care Physicians And The Cost Of U.S. Health Care. Health Aff. 2008;27:813–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartman M, Martin A, McDonnell P, Catlin A the National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National Health Spending In 2007: Slower Drug Spending Contributes To Lowest Rate Of Overall Growth Since 1998. Health Aff. 2009;28:246–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aitken M, Berndt ER, Cutler DM. Prescription Drug Spending Trends In The United States: Looking Beyond The Turning Point. Health Aff. 2009;28:w151–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aspinall SL, Berlin JA, Zhang Y, Metlay JP. Facility-level variation in antibiotic prescriptions for veterans with upper respiratory infections. Clin Ther. 2005;27:258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox ER, Motheral BR, Henderson RR, Mager D. Geographic variation in the prevalence of stimulant medication use among children 5 to 14 years old: results from a commercially insured US sample. Pediatrics. 2003;111:237–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois RW, Batchlor E, Wade S. Geographic Variation In The Use Of Medications: Is Uniformity Good News Or Bad? Health Aff. 2002;21:240–50. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fultz SL, Good CB, Kelley ME, Fine MJ. P&T. Vol. 29. 2004. Increased Costs of Diabetes Therapy not Related to Glycemic Control at Three Veterans Affairs Medical Outpatient Clinics; pp. 500–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, Campbell J. Trend and variation of prescription drug cost in the veterans health-care system. Health Serv Manage Res. 2008;21:14–22. doi: 10.1258/hsmr.2007.007009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1159–80. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez J, Meier J, Cunningham F, Siegel D. Antihypertensive medication use in the department of veterans affairs. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1095–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinman MA, Yang KY, Byron SC, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Variation in Outpatient Antibiotic Prescribing in the United States. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:861–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who Has Diabetes? Best Estimates of Diabetes Prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs Based on Computerized Patient Data. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:B10–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. VHA Enrollment, Patients and Expenditures. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Veterans Affairs Intranet Site; 2008. [Sept 1, 2009]. Available at http://vaww.va.gov/vhaopp/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. [August 1, 2009];2009 July; at http://www.pbm.va.gov/NationalFormulary.aspx.

- 20.Sales MM, Cunningham FE, Glassman PA, Valentino MA, Good CB. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration: 1995 to 2003. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS & Quality Measurement 2009. [April 10, 2009]; at http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/59/Default.aspx.

- 22.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Steinman MA, Peabody JW, Ayanian John Z. Quality of Ambulatory Care for Women and Men in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:762–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolen S, Feldman L, Vassy J, et al. Systematic Review: Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Oral Medications for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:386–99. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326:1423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gellad WF, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Implications of recent clinical trials on pay-for-performance. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:864–7. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefos T, LaVallee N, Holden F. Fairness in prospective payment: a clustering approach. Health Serv Res. 1992;27:239–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yano EM, Wright S, Cuerdon T. Organizational Complexity: Does it Reflect Differences in Structure and Management Process at Individual VAMCs? HSR&D 2009 National Meeting Abstracts. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang PY, Yano EM, Lee ML, Chang BL, Rubenstein LV. Variations in nurse practitioner use in Veterans Affairs primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:887–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank RG. Prescription drug prices: why do some pay more than others do? Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:115–28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gellad WF, Choudhry NK, Friedberg MW, Brookhart MA, Haas JS, Shrank William H. Variation in Drug Prices at Pharmacies: Are Prices Higher in Poorer Areas? Health Services Research. 2009;44:606–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redelmeier DA, Bell CM, Detsky AS, Pansegrau GK. Charges for Medical Care at Different Hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1417–22. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellerstein JK. The importance of the physician in the generic versus trade-name prescription decision. Rand J Econ. 1998;29:108–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashton CM, Petersen NJ, Souchek J, et al. Geographic Variations in Utilization Rates in Veterans Affairs Hospitals and Clinics. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:32–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH. Creating a culture of quality: the remarkable transformation of the department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:316–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:272–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Good CB, Valentino M. Access to affordable medications: the Department of Veterans Affairs pharmacy plan as a national model. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2129–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]