Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Treatment of Nighttime GERD

Nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common condition in the United States, affecting 10% of adults according to a national random-sample telephone survey.1 In another telephone survey, of 1000 adults with heartburn, 79% of respondents said that they experienced symptoms at night; of the respondents with nighttime heartburn, 75% said that symptoms affected their sleep and 40% believed that the symptoms affected their ability to function the following day, illustrating that nocturnal GERD can have a substantial impact on quality of life.2 The national random survey showed that persons with nocturnal GERD had significantly more pain than did respondents with hypertension and diabetes (P <.001) and experienced pain similar to persons with angina and congestive heart failure.1

In addition to the pain and quality-of-life consequences, nocturnal GERD is associated with other health risks, including esophagitis and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Esophageal pH monitoring over a 24-hour period has shown that an increased number of recumbent reflux episodes greater than 5 minutes in duration is the best measure for predicting patients that have erosive versus nonerosive esophagitis.3 A population-based case control study in Sweden revealed a nearly 8-fold increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma among individuals with recurrent reflux (heartburn, regurgitation, or both at least weekly) versus those without reflux. The relative risk increased to 10.8-fold among persons with nocturnal symptoms, showing a strong association between the two conditions.4

Etiology of GERD

Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) are thought to be the primary mechanism of GERD. However, TLESRs do not appear to be the cause of reflux disease, based on esophageal manometry and pH monitoring of individuals with and without GERD.5 Bredenoord and colleagues found that among 12 patients with GERD and 12 controls, the patients with GERD swallowed more air, belched more, and had more acid reflux than controls over a 24-hour period.6 However, a 600 mL air infusion did not significantly increase the incidence of acid and weakly acidic reflux episodes in either group. Observed increases in TLESRs were attributed solely to an increase in gas reflux-associated TLESRs. The authors therefore concluded that air swallowing was not causing the reflux in these patients.

Although the causes of nocturnal GERD remain undefined, both genetic and nongenetic factors have been implicated in its development. Persons with respiratory conditions are at an increased risk of having GERD. Asthma was associated with a 60% increase in the incidence of GERD after adjusting for use of asthma medication in a population-based study of more than 65,000 persons in Norway.7 In the same study, severity of reflux symptoms increased significantly with the degree of breathlessness. Body weight is also a significant factor: overweight and obese persons are significantly more likely to have reflux symptoms. Even within the normal weight range, gaining the weight equivalent to an increase in body-mass index (BMI) of 3.5 triples a woman's risk of having frequent reflux symptoms compared with women who maintain their weight.8

Nocturnal GERD

As reflected in the differential risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma between patients with GERD and nocturnal GERD, the timing of reflux symptoms appears to significantly affect their clinical significance. Although nocturnal reflux events occur less frequently than daytime events, they appear to be more severe. During the day, reflux generally occurs in short bursts after a meal. Nocturnal events are more prolonged and therefore expose the esophagus to acid for a longer period of time. Physiological responses to esophageal acid exposure also differ between night and day.9,10 During the day, the body responds to acid exposure by increasing salivary flow and peristalsis. These actions, which help clear the reflux and promote acid neutralization, do not occur at night, leading to prolonged acid exposure.

Evaluated treatments for nocturnal GERD have ranged from lifestyle changes to pharmacologic therapy. In a meta-analysis of 100 studies evaluating lifestyle modifications, weight loss appeared to provide a significant benefit, improving both esophageal pH profiles and GERD symptoms.11 Changing one's sleep position reduced the duration of esophageal acid exposure. However, neither dietary changes nor abstinence from tobacco and alcohol appeared to improve symptoms of GERD.

Over-the-counter medications are a popular treatment option among patients, although they often do not provide adequate relief. In the national telephone survey, 71% of respondents with nocturnal heartburn reported using over-the-counter medication, though only 29% considered these treatments extremely effective.2 Satisfaction with prescription agents was somewhat better: 41% had used prescription medications for GERD and 49% considered their treatment extremely effective.

Proton Pump Inhibitor Treatment for Nocturnal GERD

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) act by suppressing acid secretion and minimizing intragastric volume and the effects of acidic gastric refluxate on the esophageal mucosa. Although H2-receptor antagonists are also used for treating GERD, a meta-analysis of 7635 patients in 43 randomized trials showed that PPIs offer more complete and faster symptom relief.12 Delayed-release PPIs provide effective acid control during the day, but many patients still have significant gastric acidity at night. Omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate (Zegerid®, Santarus, Inc.) is an immediate-release oral PPI, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, which has demonstrated efficacy in patients with nocturnal GERD.

In an open-label, randomized crossover study of 36 patients with nocturnal GERD, once-daily immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 40 mg taken at bedtime provided better nocturnal acid control than once-daily or twice-daily delayed-release pantoprazole as measured by median pH (4.7, 2.0, and 1.7, respectively; P<.001), percentage of time with pH >4 (55%, 27%, and 34%, respectively; P<.001), and proportion of patients with nocturnal acid breakthrough (53%, 78%, and 75%, respectively; P<.001).13

In a separate study of 54 patients, gastric pH monitoring showed that once-daily bedtime dosing of immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 40 mg provided better nocturnal gastric acid control than once-daily bedtime dosing of lansoprazole 30 mg as measured by the proportion of time with gastric pH greater than 4 (53.4% vs 34.2%; P<.001) and median gastric pH (4.04 vs 2.09; P<.001) during the nighttime interval (2200-600 hrs). Although immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate provided superior gastric acid control compared to esomeprazole 40 mg during the first half of the night, when pathological acid reflux is more frequent, both agents performed comparably in terms of overall control of nocturnal gastric acidity.14

References

- 1.Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, et al. The impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:45–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaker R, Castell DO, Schoenfeld PS, Spechler SJ. Nighttime heartburn is an underappreciated clinical problem that impacts sleep and daytime function: the results of a Gallup survey conducted on behalf of the American Gastroenterological Association. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1487–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orr WC, Allen ML, Robinson M. The pattern of nocturnal and diurnal esophageal acid exposure in the pathogenesis of erosive mucosal damage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwakiri K, Hayashi Y, Kotoyori M, et al. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) are the major mechanism of gastroesophageal reflux but are not the cause of reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1072–1077. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Air swallowing, belching, and reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1721–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordenstedt H, Nilsson M, Johansson S, et al. The relation between gastroesophageal reflux and respiratory symptoms in a population-based study: the Nord-Trondelag health survey. Chest. 2006;129:1051–1056. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.4.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA., Jr. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2340–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orr WC. Sleep issues in gastroesophageal reflux disease: beyond simple heartburn control. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2003;3(Suppl 4):S22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, Mishra A, Naik SR. Inclusion of supine period in short-duration pH monitoring is essential in diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:764–772. doi: 10.1007/BF02213133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965–971. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, et al. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798–1810. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castell D, Bagin R, Goldlust B, Major J, Hepburn B. Comparison of the effects of omeprazole immediate-release powder for oral suspension and pantoprazole delayed-release tablets on nocturnal acid breakthrough in patients with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1467–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz PO, Ballard ED, Koch FK, Bagin RG, Gautille TC. Nocturnal gastric acidity after bedtime dosing of proton pump inhibitors in patients with nighttime GERD symtpoms. Presented at Digestive Disease Week 2006; Los Angeles, California. 2006. May 20-25.

Bravo pH Testing On and Off Treatment With Immediate-Release Omeprazole

A Review of: Effect of PPI Therapy on Symptom Association Using Four-Day Bravo pH Recording Combining 48-Hour Periods Off and On Therapy

CP Garrean, N Gonsalves, I Hirano

Although 24-hour monitoring can be informative, longer monitoring periods have been evaluated and may provide a more complete picture of the gastric acidity as it occurs over time. The Bravo® pH monitoring system (Medtronic) is a wireless device that allows the collection of 48 hours of pH data. Among 90 consecutive patients with persistent reflux symptoms, the system successfully collected pH data over 48 hours in 90% of patients.1 The frequency of reflux events and the proportion of time with pH less than 4 were similar in the first 24 hours and the second 24 hours in 74.4% of patients. Although various adverse effects, including the sensation of a foreign body and chest discomfort or pain, were reported by nearly two-thirds of patients during the study, no patients withdrew because of them. Early endoscopic removal of the capsule was required in 3 patients due to chest pain.

Prakash and Clouse demonstrated that two-day wireless pH monitoring is more effective than one-day monitoring in detecting abnormal esophageal acid exposure and reflux symptom association.2 Monitoring can be done while patients are off-therapy or on-therapy, though controversy remains regarding the best method. Although off-therapy testing may yield the greatest symptom association, on-therapy testing can evaluate the efficacy of treatment by measuring the normalization of esophageal acid exposure.

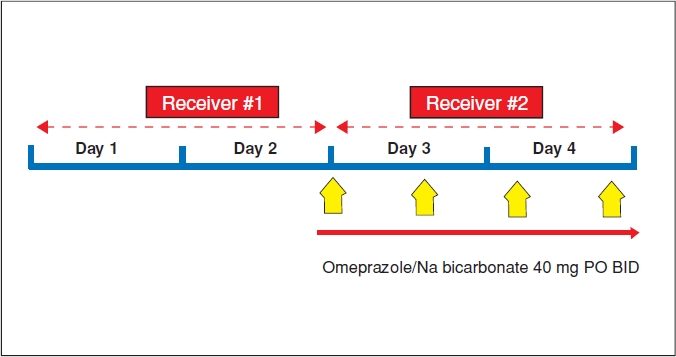

Using a modified monitoring technique, both offtreatment and on-treatment measurements can be taken. In this 4-day test, two separate receivers are calibrated to a single Bravo pH capsule and measurements are taken during periods when the patient is on and off therapy.3 In a study presented at the 2006 annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, Garrean and colleagues used this method to measure the effect of PPI therapy on symptom association in 12 patients with refractory heartburn (n=6), chest pain (n=4), chronic cough (n=1) or chronic laryngeal symptoms (n=1).4 An additional 3 patients were excluded from analysis due to premature detachment of the capsule or due to a malfunction in data transmission. Patients were off-therapy for the first two days then received omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate 40 mg twice a day for days 3 and 4. See Figure 1. Patients were encouraged to continue their usual daily activities and diet. During the study, patients documented their sleep patterns, food intake, medication use, symptoms (including heartburn, regurgitation, or chest pain), and any adverse effects of the capsule. To analyze symptom association, the investigators calculated two indices: the symptom index (SI), defined as the ratio of reflux-associated symptoms to the total number of symptoms in a 24-hour period, and the symptom association probability (SAP), which was manually calculated using 2-minute windows of symptom and reflux events.

Figure 1.

pH recording protocol in the study by Garrean and associates.

Abnormal esophageal acid exposure, defined as greater than 5.3% of a 24-hour period, was detected in 7 patients (58%) off therapy versus only 1 patient (8%) on therapy, indicating that persistent abnormal esophageal acid reflux is uncommon on twice-daily immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate. The proportion of time with esophageal pH less than 4 was significantly decreased on day 4 compared to day 1 (P<.01; Figure 2). On day 4 of monitoring, 5 patients had an esophageal pH less than 4 for less than 1% of the time, while 3 patients (25%) had no time with a pH less than 4.

Figure 2.

Percentage of time with esophageal pH less than 4 for each day of the 4-day study.

- PPI

- proton-pump inhibitor.

Comparing the reported symptoms with the pH recordings revealed both non-reflux-associated symptoms (SAP <95%) and reflux-associated symptoms (Figure 3). The SAP decreased significantly on day 4 versus day 1 (P<.05), and 7 patients (58%) continued to experience non-reflux-associated symptoms while on PPI therapy (SAP <95%). See Figure 4. Although the SI also decreased after PPI therapy, this reduction did not reach statistical significance. These findings indicate that PPI therapy substantially reduces the yield of symptomassociation indices.

Figure 3.

Sample 4-day esophageal pH recording off and on proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

- HB

- heartburn.

Figure 4.

(A) Symptom index and (B) symptom association probability (SAP) for each day of the 4-day study.

*P<0.05 Day 1 vs Day 4

These recent studies show that treating nocturnal GERD with PPIs such as immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate appears to effectively control gastric and esophageal acidity. The use of advanced monitoring techniques in patients both on and off treatment should continue to provide important information about the effectiveness of treatments for reducing reflux and its associated symptoms.

References

- 1.Ahlawat SK, Novak DJ, Williams DC, Maher KA, Barton F, Benjamin SB. Day-to-day variability in acid reflux patterns using the BRAVO pH monitoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:20–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000190753.25750.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Value of extended recording time with wireless pH monitoring in evaluating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:329–334. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirano I, Zhang Q, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Four-day Bravo pH capsule monitoring with and without proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00529-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrean CP, Gonsalves N, Hirano I. Las Vegas: Nevada; Oct 20-25, 2006. Effect of PPI therapy on symptom association using four-day Bravo pH recording combining 48-hour periods off and on PPI. American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting 2006. [Google Scholar]

Commentary

Traditionally, a catheter-based system has been used to assess potential abnormal esophageal acid exposure in patients presenting with various GERD-associated symptoms. These systems have historically been problematic in that patients do not tolerate them well, due to the physical discomfort associated with catheter placement. Monitoring with these systems generally prevents patients from going to work or performing daily activities, which can affect the sensitivity of the test. At best, catheter-based systems are able to detect abnormal acid with a sensitivity of only 70–80%.

Because of these factors, monitoring with the Bravo pH system represents, in my opinion, a great advancement in increasing the sensitivity of esophageal acid monitoring. If patients are more likely to conduct their daily activities in a normal fashion and maintain their normal diet, the monitoring is more representative of their real-life levels of acid exposure. Furthermore, whereas catheter-based systems only provide monitoring for one day, the Bravo system monitors for extended periods and provides information on the day-to-day variability in acid exposure that some patients experience. In this manner, the Bravo system provides a much better understanding of whether or not patients are experiencing abnormal acid exposure in their regular lives.

In addition, because the Bravo capsule may stay in place for up to 7 days, it can provide clinicians with an opportunity to study patients both off and on therapy. If patients are studied off therapy for the first two days, they can then begin receiving their medication in order to gauge the effect of treatment on abnormal esophageal acid exposure. Dr. Hirano at Northwestern University is the leader in this type of monitoring and has presented abstracts over the last several years, looking at the results of continuous monitoring off and on therapy. He and his colleagues have shown that it is feasible for use in the clinical setting.

This particular abstract goes beyond feasibility of off- and on-therapy monitoring to examine symptom association. The study examines events of reflux both off and on therapy and determines the likelihood that a patient who is on therapy might still have abnormal reflux events and whether or not those events are associated with symptoms. This is information that will help in the management of patients, particularly those that may continue to have symptoms despite active therapy. Overall, this is a step forward in our care of patients who not only have reflux but may also have some difficult-to-treat reflux symptoms.

In terms of intermittent or on-demand therapy, this study shows that, at least for the two days of the study that patients are on therapy, this method or pattern of administration is most likely effective. This is an important conclusion in that we have prior studies showing that patients often take their medications on demand, regardless of how they are prescribed. As data accumulate regarding on-demand therapy, it will most likely evolve as an alternative to continuous treatment, rather than an add-on therapy. In this study of immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate, we can see that it is an effective agent in suppressing gastric acid in the two-day span of monitoring, which shows it to be a viable alternative, providing comprehensive relief.

The next step for this research will be to perform a similar study on a much larger scale. Here, with a population of only 15 patients, Dr. Hirano and his colleagues have nicely shown that 1) Bravo pH monitoring is useful and 2) treatment with immediate-release omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate effectively suppresses acid exposure and symptoms. If these results and benefits can be replicated in a large-scale study, and I have no doubt that they will, this kind of monitoring and therapy will become an important part of our overall treatment strategies. It will be of particular importance to examine this technique of monitoring and therapy in our patients with extraesophageal symptoms and refractory GERD, with whom we are currently struggling to achieve effective treatment.

Suggested Reading

- Charbel S, Khandwala F, Vaezi MF. The role of esophageal pH monitoring in symptomatic patients on PPI therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano I, Zhang Q, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Four-day Bravo pH capsule monitoring with and without proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00529-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakil N. Novel methods of using proton-pump inhibitors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:S85–S88. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(02)00043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JE. The patient with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PO. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and extraesophageal disease. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2005;5:S31–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]