Abstract

A 65-year-old Hispanic man receiving peritoneal dialysis presented to the emergency department complaining of the sudden onset of numbness and tingling of the right side of his body and face with associated nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and blurry vision. Further testing revealed a large, mobile mass on his mitral valve, leading to a diagnosis of endocarditis with embolic phenomena. The presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of endocarditis are discussed here.

Keywords: Embolic phenomena, endocarditis, infective endocarditis

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old Hispanic man presented to the emergency department complaining of the sudden onset of numbness and tingling of the right side of his body and face with associated nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and blurry vision. He also complained of a 1-day history of generalized weakness and mild headache but denied fever, dyspnea, anorexia, weight loss, or any flulike symptoms.

His past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and end-stage renal disease managed with peritoneal dialysis. Three months prior to admission, the patient underwent a fistulogram and revascularization of his arteriovenous fistula that was reserved for emergent hemodialysis.

Vital signs included a blood pressure of 174/108 mmHg and a heart rate of 104 beats per minute. On physical examination, a right facial droop with ptosis of the right eye was evident along with decreased strength (4/5) and sensation in the right upper and lower extremities. The cardiovascular examination revealed normal first and second heart sounds; no murmurs were appreciated. Routine laboratory testing yielded a white blood cell count of 13.8 × 103/µL with a differential of 86.2% granulocytes, an elevated blood urea nitrogen level of 30 mg/dL, and a serum creatinine level of 11.2 mg/dL. The remainder of his results were unremarkable.

A noncontrast computed tomography of the brain did not reveal any significant abnormalities. In particular, there was no evidence of an acute cerebrovascular infarction or intracranial hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography and computed tomographic angiography also yielded no abnormalities. However, in light of the patient's signs and symptoms, brainstem infarction was still suspected and a diagnosis of basilar artery stroke was made following consultation with Neurology. Further evaluation with transthoracic echocardiogram was recommended.

Which of the following abnormalities is most likely, given the patient's presentation and transthoracic echocardiogram findings shown here (Figures 1 and 2)?

Figure 1.

2-dimensional echocardiogram.

Figure 2.

2-dimensional echocardiogram with Doppler ultrasound.

(A) Mural thrombus

(B) Valvular vegetation

(C) Atrial myxoma

(D) Valve ring abscess

ANSWER

The correct answer is (B), valvular vegetation.

The transthoracic echocardiogram showed a pedunculated echogenic mass, 1.5 × 0.7 cm in size, affixed to the anterior mitral valve leaflet. The mass was mobile within the left ventricle and likely represented valvular vegetation. There was also associated mild to moderate mitral regurgitation. A presumptive diagnosis of subacute bacterial endocarditis was made on the basis of the echocardiogram. Vegetations that are >10 mm in diameter and those located on the mitral valve are more likely to embolize than vegetations that are smaller or nonmitral.1–3 Arterial emboli are clinically apparent in up to 50% of patients with endocarditis.

A mural thrombus most commonly occurs in the left ventricle and appears as an echodense structure, usually in the apical region associated with regional wall motion abnormalities.4 An atrial myxoma can be diagnosed by the appearance of a well-circumscribed mobile mass with attachments to the atrial septum.5 The mass described here is attached to a mitral valve leaflet. A valve ring abscess is diagnosed as an echo-free area within the echodense valvular ring region and occurs more commonly in the aortic root or aortic valve area.6

CLINICAL COURSE OF CASE PATIENT

After the echocardiogram was interpreted, blood cultures were collected and the infectious disease team was consulted for further management recommendations. The large size of the vegetation (>10 mm) along with its hypermobile nature and increased risk of embolization were indications for cardiac surgical intervention. However, the patient's recent history of stroke, combined with his comorbidities, made him an unfavorable surgical candidate.

It was suspected that inoculation could have occurred during the arteriovenous fistula declotting procedure 3 months earlier. The patient is currently receiving vancomycin and gentamicin at doses adjusted for his renal function.

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Infective endocarditis (IE), previously referred to as bacterial endocarditis, is defined as an infection of the endocardial surface of the heart that may include 1 or more heart valves, the mural endocardium, or a septal defect. It generally occurs as a consequence of turbulence or trauma to the endothelial surface of the heart. Transient bacteremia then leads to seeding of lesions with adherent bacteria, which causes IE to develop.

Microbiology and Risk Factors

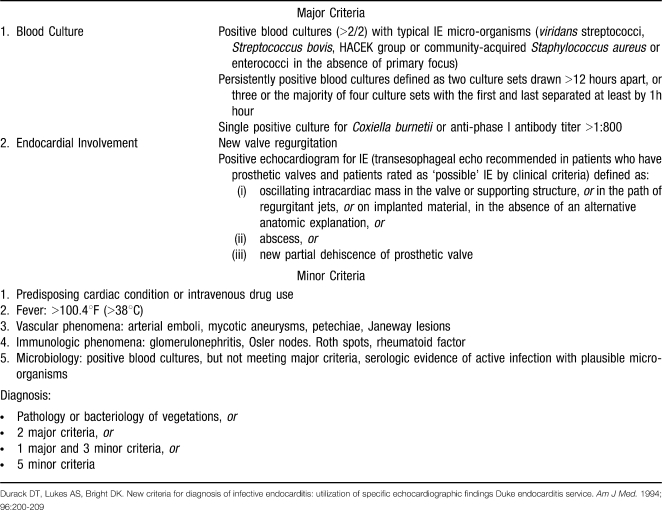

Although the pathogens vary with the clinical types of endocarditis, staphylococci and streptococci account for the majority of cases (42% and 40%, respectively).7 Other less common pathogens include Enterococcus, HACEK organisms (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella), non-HACEK gram-negative bacteria, and fungi. The Duke criteria (Table), a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic scheme based on clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic findings, define the following organisms as “typical causes” of IE: Staphylococcus aureus, viridans streptococci, Streptococcus bovis, Enterococcus, and HACEK organisms.8,9

MODIFIED DUKE CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

A number of factors predispose a patient to the development of IE, with the most common being injection drug use, prosthetic heart valves, and structural heart disease. Classically, injection drug use is associated with right-sided IE, with the most common pathogen being S aureus, many of which are methicillin resistant.10 Prosthetic valve endocarditis has the greatest risk of occurring during the initial 3 months after surgery. The type of prosthetic valve does not have an impact on the development of IE.11 The majority of patients with IE have a pre-existing structural heart defect, the most common of which is mitral valve prolapse.12 Other risk factors associated with IE include a history of IE, hemodialysis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical syndrome of IE is highly variable and can range between acute and subacute presentations. The most common clinical and laboratory features of IE include fever, heart murmur, anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated C-reactive protein.13 Physical examination should include a careful cardiac examination for signs of new, regurgitant murmurs or heart failure. Attention should also be paid to noncardiac manifestations such as petechiae, Osler nodes (painful palpable nodules on the tips of the fingers), Roth spots (round retinal hemorrhages with white centers), Janeway lesions (nontender, erythematous lesions on the palms and soles), and splinter hemorrhages (small, asymptomatic linear hemorrhages under the nails). Patients with IE may also present with signs and symptoms secondary to embolic phenomena (e.g., stroke, as in our patient), systemic immune reactions (glomerulonephritis and arthritis), and shortness of breath (septic pulmonary infarcts).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IE is established with certainty only by a positive culture for vegetation or embolus or by histologic confirmation of a vegetation or embolus. In most cases, this is obtained only at cardiac surgery or autopsy. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) may confirm the diagnosis of IE if vegetation is detected. However, TTE has a relatively low sensitivity for vegetations in IE. If TTE has negative findings and IE is still suspected, transesophageal echocardiography is usually warranted. It is also reasonable to begin diagnosis with transesophageal echocardiography in high-risk patients (e.g., those with prosthetic heart valves or prior endocarditis) or if there is high clinical suspicion of IE.8

Treatment

Eradication of bacteria in IE is difficult because of the avascular nature of vegetations and the deficiency of host defenses in those areas. Therefore, therapy is bactericidal and prolonged. Antibiotics are usually given parenterally and are tailored based on the susceptibility of the causative organisms.14,15 In some cases, surgical intervention is required for effective treatment of the complications of IE. Indications for surgery include moderate to severe congestive heart failure due to valve dysfunction, persistent bacteremia despite optimal antibiotic therapy, partially dehisced unstable prosthetic valve, lack of effective microbicidal therapy (e.g., fungal or Brucella endocarditis), S aureus prosthetic valve endocarditis with an intracardiac complication, or relapse of prosthetic valve endocarditis after optimal antimicrobial therapy. Other situations in which surgery is to be strongly considered include perivalvular extension of infection, large (>10 mm diameter) hypermobile vegetations with increased risk of embolism, and persistent fever.16,17

REFERENCES

- 1.Di Salvo G., Habib G., Pergola V., et al. Echocardiography predicts embolic events in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37((4)):1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mügge A., Daniel W. G., Gunter F., Lichtlen P. R. Echocardiography in infective endocarditis: reassessment of prognostic implications of vegetation size determined by the transthoracic and the transesophageal approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14((3)):631–638. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vilacosta I., Graupner C., San Román J. A., et al. Risk of embolization after institution of antibiotic therapy for infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39((9)):1489–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeder G. S., Tajik A. J., Seward J. B. Left ventricular mural thrombus: two-dimensional echocardiographic diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56((2)):82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry L. S., King J. F., Zeft H. J., Manley J. C., Gross C. M., Wann L. S. Two-dimensional echocardiography in the diagnosis of left atrial myxoma. Br Heart J. 1981;45((6)):667–671. doi: 10.1136/hrt.45.6.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo G., Tamburino C., Greco G., et al. Echocardiographic detection of aortic valve ring abscesses. J Ultrasound Med. 1990;9((6)):319–323. doi: 10.7863/jum.1990.9.6.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler V. G., Jr, Miro J. M., Hoen B., et al. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: a consequence of medical progress. JAMA. 2005;293((24)):3012–3021. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.24.3012. Erratum in: JAMA. 2005;294(8):900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durack D. T., Lukes A. S., Bright D. K. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med. 1994;96((3)):200–209. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J. S., Sexton D. J., Mick N., et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis [published online ahead of print April 3, 2000] Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30((4)):633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. doi:10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathew J., Addai T., Anand A., Morrobel A., Maheshwari P., Freels S. Clinical features, site of involvement, bacteriologic findings, and outcome of infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155((15)):1641–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutledge R., Kim B. J., Applebaum R. E. Actuarial analysis of the risk of prosthetic valve endocarditis in 1,598 patients with mechanical and bioprosthetic valves. Arch Surg. 1985;120((4)):469–472. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390280061013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinsey D. S., Ratts T. E., Bisno A. L. Underlying cardiac lesions in adults with infective endocarditis: the changing spectrum. Am J Med. 1987;82((4)):681–688. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fauci A. S., Braunwald E., Kasper D. L., et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 789–798. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heldman A. W., Hartert T. V., Ray S. C., et al. Oral antibiotic treatment of right-sided staphylococcal endocarditis in injection drug users: prospective randomized comparison with parenteral therapy. Am J Med. 1996;101((1)):68–76. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehm S. J. Outpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy for endocarditis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998;12((4)):879–901. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonow R. O., Carabello B. A., Chatterjee K., et al. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease); Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48((3)):e1–e148. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.021. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(9):1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moon M. R., Stinson E. B., Miller D. C. Surgical treatment of endocarditis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1997;40((3)):239–264. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(97)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]