Abstract

Alton Ochsner was a giant of American surgery. His career encompassed patient care, teaching, and research as symbolized on the original seal of the Ochsner Clinic. His ideas were innovative and groundbreaking on many fronts, making him and the Ochsner Clinic nationally and internationally known. Examination of his card file, a simple metal box with 3 × 5 index cards and subject dividers, gives extraordinary insight into the professional interests of this remarkable physician and surgeon.

Keywords: Card file, history, Ochsner

INTRODUCTION

The history of the Ochsner Clinic and its namesake founder has been well chronicled.1–3 Recordings of excerpts of his lectures have been made available by the Ochsner Division of Philanthropy and give yet more insight into his philosophies and character.4 I was not fortunate to have known Dr Alton Ochsner during his lifetime. However, I did have the privilege of receiving fellowship training at the Ochsner Clinic under Dr John Ochsner and have benefited from the Ochsner tradition. In the late 1990s I received Alton Ochsner's card file from John Ochsner. After several years on my library shelf, I examined it while researching an article on Rudolph Matas,5 whom Alton Ochnser succeeded as Chairman of the Department of Surgery of Tulane University School of Medicine.6 It was a pleasant surprise to find a unique profile of medical history and insight into a giant of American surgery.7,8 That card file is the basis for this contribution.

THE CARD FILE

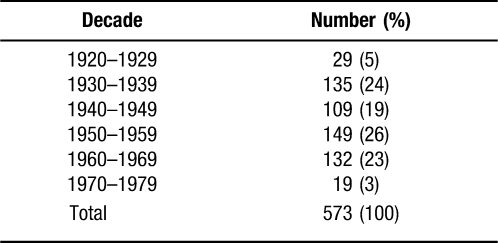

The card file is a simple metal box (Figure 1) with subject dividers and references typed on one side of plain or lined 3 × 5 index cards. Minor corrections of references and notes were made in pencil by Alton Ochsner. There are 74 subject sections that contain a total of 573 individual card references and 49 cross-references from a given section to others (Table 1). All were authored by Alton Ochsner. The references are to articles, monographs, book chapters, and presentations. All were published. The card file covers nearly 50 years, with the earliest entry being 1923 and the latest being 1971. It spanned such major 20th century events as the Great Depression and World War II. Broken down by decade, the most prolific period was 1950–1959 (Table 2). Not surprisingly, the topics most populated are “Cancer Lung” followed by “Medicine, General” and “Cancer Bronchogenic.” Of particular interest are those topics relating to medical history, medical education and surgical training, and professional ethics. These topics are covered across several sections (Education Medical; Executive Obsolescence; Group Hospitalization; Group Practice; Medicine, General; and Surgery). All are nonclinical in scope. These sections cover his ideas across the wide spectrum of medicine as a profession.

Figure 1.

Alton Ochsner's card file

(courtesy of the author).

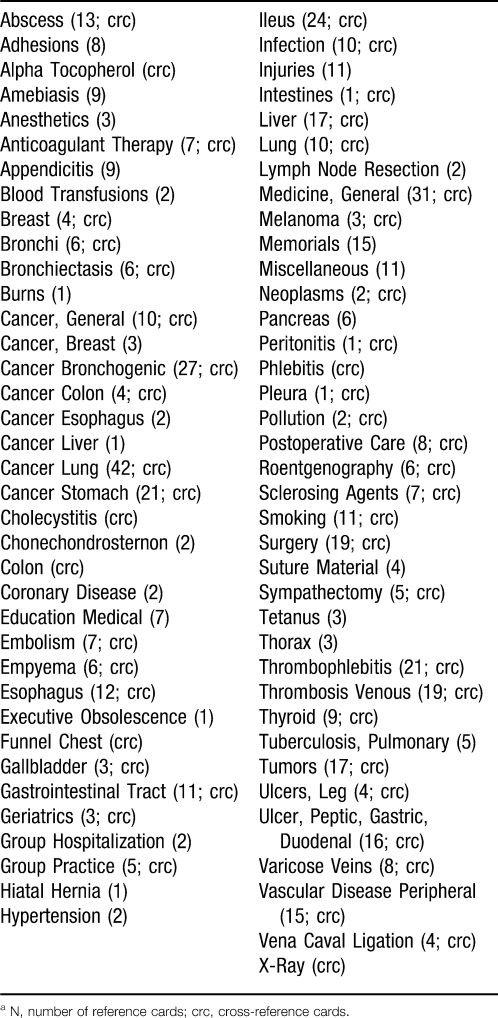

Table 1.

Section Headings in the Card Filea

Table 2.

Alton Ochsner Card File: References by Decade

Dr Ochsner's appreciation of medical history is illustrated in the “Memorials” section. His articles regarding Rudolph Matas, whom he called “that unfailing and inexhaustible source of knowledge,”9 are especially poignant.10–13

THORACIC AND VASCULAR SURGERY

His surgical career was all encompassing. Specialization would evolve during his lifetime. It is worthwhile to look at 2 clinical arenas in which his pupil, Michael E. DeBakey, and his son, John L. Ochsner, would become renowned. In fact, Michael DeBakey was coauthor on 107 of the clinical contributions. John Ochsner would receive training under DeBakey in Houston. Several sections, when grouped together, give a solid profile of thoracic surgery of that era. These sections include Bronchi; Bronchiectasis; Cancer Bronchogenic; Cancer Esophagus; Cancer Lung; Chonechondrosternon; Coronary Disease; Empyema; Esophagus; Funnel Chest; Lung; Pleura; Pollution; Smoking; Thorax; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary; and Tumors. These references sum to 154, or 27% of the overall total.

With regard to peripheral vascular disease, the following sections give an interesting profile in the evolution of vascular surgery as a specialty: Alpha Tocopherol; Anticoagulant Therapy; Embolism; Phlebitis; Sclerosing Agents; Sympathectomy; Thrombophlebitis; Thrombosis Venous; Ulcers, Leg; Varicose Veins; Vascular Disease Peripheral; and Vena Caval Ligation. These sections sum to 97, or 17% of the overall total.

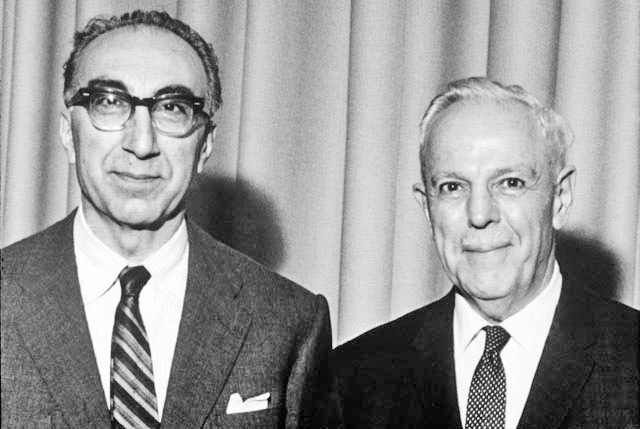

The collaborative treatises of Ochsner and DeBakey (Figure 2) on coronary artery disease in 193714 and peripheral vascular disease in 1939 and 194015,16 were lengthy, detailed, and comprehensive for the day. Thoracic and vascular surgery accounted for nearly half (44%) of his reference cards. Clearly, this simple analysis could be applied in regard to other areas such as surgical oncology or gastrointestinal surgery and would likely reveal similar results, demonstrating the depth of his surgical career.

Figure 2.

Alton Ochsner (right) and Michael DeBakey (left)

(courtesy of Ochsner Medical Library and Archives, reproduced with permission).

OBSERVATIONS

When the individual cards are examined, it is of interest to note the coauthors, subject matter, date, journal name, and language. The diversity of the publications gives testimony to the depth of his professional career and illustrates the wide breadth of his interests and influence. This breadth of knowledge and influence was remarkable. No topics were too petty to discover. No subject was too unimportant on which to elaborate. No journal was too small in which to publish. No case was too isolated to report. No group, venue, or forum was too minor to address. This card file is local, regional, national, and international in scope. In addition to the nation as a whole, Ochsner shared his knowledge and medical information with cities, states, and foreign countries. Ever the educator, he was published in 17 different state medical journals and authored “Surgery” for Britannica's Book of the Year from 1959 to 1963. He stressed the importance of the National Library of Medicine in 195617 and surveyed the readership of the journal Surgery, which he edited, to better determine what surgical information would best serve its readers in 1960.18

His thoughts on graduate training in surgery, published in 1938, demonstrate sound principles that are very relevant today.19,20 He clearly had a passion for medical education,21–23 surgical training,19,24 and organized medicine.25 He held the profession in the highest esteem.26,27 He believed a reciprocal relationship existed between physicians and patients to their mutual benefit.28 He believed that both general practitioners (now primary care physicians) and specialists, working together, offered optimal patient care,29,30 and that scrupulously honest reporting of results led to true advances in the inexact science of medicine.31 He advocated practicing medicine based on laboratory research and sound scientific principles and not empirical evidence.32 His article detailing the hospital's treatment of patients' relatives is a classic treatise that should be read by all physicians and surgeons, and it is a tribute to the Ochsner Clinic.33 His perspective was global and he believed the brotherhood of medicine transcended geographical and societal borders. He encouraged involvement in political and cultural affairs as well as reaching across barriers with medicine as a bridge.34–37

He was in favor of group hospitalization plans in the 1930s.38,39 His 1945 article regarding the post-World War II problems and challenges facing medicine was prophetic.40 His comments at the time on government-controlled health care are not unlike those heard today, 65 years later: “It would be extremely undesirable for the program to be controlled by the government because the character of the medicine practiced would be definitely inferior, much more expensive, and less efficient.” Also, “The principle of free choice of physicians and hospital by the patient must be assured to the end that the responsibility of the individual physician to the individual patient will always be maintained.” He was an advocate of group practice and thought it to be a significant advantage as specialization and Medicare impacted medicine.41,42 In 1966 he predicted that one day the entire medical record could be put on tape, saving paper and space, noting “the practice of medicine is going to become increasingly more difficult.”42

Three articles offer a unique trilogy encompassing the seasons of one's entire professional life. Aptly titled “The Joy of Working,”43 “Success in Medicine,”44 and “Prevention of Executive Obsolescence,”45 these contributions detail timeless wisdom.

His writings reveal definitive opinions about a variety of important topics, both clinical and nonclinical. The lessons he shared are as timely today as they were when he shared them. These contributions demonstrate a career of professional leadership and one individual's guidebook for a life in medicine.

Ochsner recognized the importance of medical history. Besides his writings on Rudolph Matas, Ochsner wrote historical perspectives on surgical teaching in the United States,46 Tulane University School of Medicine,47 the role of serendipity in medical breakthroughs,48 the evolution of surgery,49 vascular surgery,50 surgery in the South,51 thoracic surgery,52 and suture material.53 Without his writings, many of us may have never known about the lives and contributions of C. Jeff Miller,54 Christian Fenger,55 William David Haggard,56 Arthur Wilburn Allen,57 Rawley Martin Penick,58 Frederick Amassa Coller,59 and Harold L. Foss.60

The clinical topics are interesting and engaging reading. For those interested in medical history, the card file is a unique text of surgical history. Perusal through the sections provides a mental picture of the clinical challenges that were faced and the efforts undertaken to overcome them. His seminal work on lung cancer, its relationship to smoking, and the surgical approach to treatment are contained in the sections mentioned previously. On the reference card for the initial report of the association between smoking and lung cancer61 is the handwritten notation: “first mention of tobacco as possible cause.” Additionally, he attacked tobacco on all fronts, ranging from the importance of an accurate patient smoking history62 to the influence of smoking on sexuality and pregnancy.63 He felt obligated to treat the whole patient,64 and in 1969 he presented a simple but elegant plea to rid society of tobacco.65

Many of the ideas presented were clearly preeminent. In the 1920s, contributions involved blood transfusions, prevention of adhesions, contrast bronchography, treatment of ileus, and skin grafting. In the 1930s, contributions included treatment of amebiasis, conservative treatment of appendiceal peritonitis, operability of colon cancer, surgical therapy of coronary artery disease, postoperative care, value of diagnostic x-rays, and peripheral arterial disease. In the 1940s and 1950s, he embraced end-of-life care for cancer patients, anticoagulation and vena caval interruption for the treatment of pulmonary emboli, association of venous thrombosis and orthopedic surgery, and postphlebitic syndrome. The excellent 1948 review of surgical practice in the United States is comprehensive and forward thinking.66 He pointed out the importance of psychiatry in the practice of surgery in 1950 with wisdom, sensitivity, and practicality.67 He discussed the importance of keeping employees well and active long before corporate wellness programs became commonplace.68 In 1962 he accurately predicted the future regarding organ transplants, heart valve replacement, cancer screening, chemotherapy, risk factor modification for heart disease, endarterectomy and stenting, vascular bypass, anesthesia, and cerebral imaging.69 His contributions in the 1960s and 1970s involved thermal energy in cancer treatment, relationship of hormones and breast cancer, and strategies for smoking cessation. Importantly, he proffered his experience in avoiding operative emergencies in 1969 with sage counsel.70

How we file, store, and retrieve knowledge has changed over the years. For many of us, the card file (and later, the reprint file) was a useful method to organize information and remain current. It is worthwhile to recognize how Alton Ochsner filed and stored information and then shared this knowledge with the world. His clinical works are well known. His nonclinical works are consistent with empathy and humanism, much like those of his predecessor Matas.13 He was dedicated to his profession and his namesake institution. The amount of knowledge in a simple, small metal box with index cards is truly remarkable, and study of it provides an insightful look into its author and the associated medical history. It is a part of the tradition, heritage, and legacy of the Ochsner Clinic. We should continue to embrace it.

EPILOGUE

The Alton Ochsner card file resides in the Ochsner Medical Library and Archives. The articles referenced in it can be obtained through the Ochsner Medical Library and Archives. They are available without charge as a benefit of lifetime membership in the Ochsner Alumni Association. Selections from this collection make for extraordinary reading, and it is worthwhile to examine the references of the individual articles for additional sources of interesting information. A published collection of these writings would be an important legacy to the future.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge Dr. John Ochsner for allowing me to be a guardian of the card file, and Ms. Judith Gardner, MLIS, and staff at the Ochsner Medical Library and Archives for their assistance in the research for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caldwell G. M. Early History of the Ochsner Medical Center. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilds J. Ochsner's: An Informal History of the South's Largest Private Medical Center. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilds J., Harkey I. Alton Ochsner, Surgeon of the South. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes J. Lessons & Reflections from a Life in Medicine: Excerpts from Lectures by Alton Ochsner, M.D. New Orleans, LA: Alton Ochsner Medical Foundation Division of Philanthropy; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trotter M. C. Rudolph Matas and the first aneurysmorrhaphy: “a fine account of this operation.”. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51((6)):1569–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeBakey M. E. Historical perspectives of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery: Alton Ochsner, MD (1896–1981) J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130((3)):875–876. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ochsner J. L. Giants. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;106((5)):769–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy J. D. Dr. Ochsner the teacher. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;84((1)):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochsner A. Women benefactors of Tulane. Bull Tulane Med Fac. 1950;9((4)):140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochsner A. Dr. Rudolph Matas. Arch Surg. 1956;72((1)):1–19. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01270190003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochsner A. Dr. Rudolph Matas. Bull Tulane Med Fac. 1958;17((2)):69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ochsner A. Rudolph Matas (1860–1957) J Thoracic Surg. 1958;36((5)):621–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ochsner A. Rudolph Matas: scientist, scholar, and humanist. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1962;3((1)):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochsner A., DeBakey M. The surgical treatment of coronary disease. Surgery. 1937;2((3)):428–455. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochsner A., DeBakey M. The rational consideration of peripheral vascular disease based on physiologic principles. JAMA. 1939;112:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochsner A., DeBakey M. Peripheral vascular disease: a critical survey of its conservative and radical treatment. SG&O. 1940;70:1058–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochsner A. The National Library of Medicine. Surgery. 1956;40((4)):787. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochsner A. Re-evaluation of the activities of surgery (editorial). Surgery. 1960;47:691–692. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochsner A. Graduate training for surgery. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1938;23:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochsner A. The value and need of coordination in the teaching of surgery. J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1937;12:86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochsner A. Introduction. Ochsner Clinic Issue. Postgrad Med. 1953;14:369. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ochsner A. To specialize or not to specialize. Bull Tulane Med Fac. 1954;13((2)):49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochsner A. The value of postgraduate education. Postgrad Med. 1957;21((2)):205–208. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1957.11691403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochsner A. Training of a vascular surgeon. Arch Surg. 1957;74((1)):1–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1957.01280070005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochsner A. A report to our founders. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1953;38:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochsner A. Looking into the future. New Orleans Med Surg J. 1932;84((12)):945–948. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochsner A. Correct speech. Surgery. 1939;6((3)):449–451. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochsner A. The physician and his patient: their reciprocal relationships. New Orleans Med Surg J. 1929;82((5)):257–261. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochsner A. What should one expect of his physician and surgeon? J Missouri State Med Assoc. 1931;28:306–309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochsner A. The need for teamwork in medical care. Group Practice. 1968;17:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochsner A. Judgment, accuracy and honesty in medical reporting. Mississippi Valley Med J. 1959;81:45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochsner A. Empiricism in medicine. SG&O. 1937;65:393–394. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochsner A. Obligation of the hospital to the patient's relatives. Hospitals. 1961;35:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ochsner A. Responsibility of medicine in the future. West J Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1964;72:52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochsner A. The physician's role in international affairs. Univ Mich Med Cent J. 1965;31:272–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochsner A. The physician's obligation to society. Am Surg. 1967;33((8)):604–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochsner A. The place of the physician in society. Synapse (Tulane School of Medicine) 1967;1 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ochsner A. Does group hospitalization help the practitioners of medicine? Trans Am Hosp Assoc. 1936;38:500–502. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ochsner A. Group hospitalization pays doctors' fees. Mod Hosp. 1936;46:74. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ochsner A. Whither anon. Ann Surg. 1945;121((4)):385–394. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194504000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ochsner A. The role of management in medicine. Proceedings from the 38th Annual Conference, Medical Group Management Association. 1964;12:4–5. In: October 20, 1964; New Orleans, LA: [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ochsner A. The future of group practice. Am J Surg. 1966;112((5)):666–669. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(66)90101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ochsner A. The joy of working. SD J Med Pharm. 1960;13((12)) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ochsner A. Success in medicine. Tr Am Acad Ophth Otol. 1967;71:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ochsner A. Prevention of executive obsolescence. J Am Geriat Soc. 1968;16((10)):1077–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ochsner A. The evolution of surgical teaching in the United States. South Med J. 1929;22((1)):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ochsner A. School of Medicine, Tulane University of Louisiana. SG&O. 1933;57:815–819. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ochsner A. The influence of serendipity on medicine. J Med Assoc Alabama. 1946;15:357–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ochsner A. Modern concepts of surgery. Bull Tulane Med Fac. 1951;10((2)):63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ochsner A. Symposium on vascular surgery [foreword] Surg Clin North Am. 1953;33:943–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ochsner A. Development of surgery in the south. JAMA. 1959;171((17)):2321–2326. doi: 10.1001/jama.1959.73010350015008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ochsner A. History of thoracic surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 1966;46((6)):1353–1376. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)38076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ochsner A. History of suture material. In: Mennie A. T., editor. Report of the Proceedings of the Symposium at the Royal College of Surgeons. London: Davis & Geck; 1971. pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ochsner A. C. Jeff Miller. SG&O. 1936;62:1024–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ochsner A. Christian Fenger. South Med J. 1938;31((4)):447–451. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mason J. M., Ochsner A. William David Haggard. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1940;25:111–112. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ochsner A. Arthur Wilburn Allen 1887–1959. Surgery. 1958;44((6)):1116–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ochsner A. Rawley Martin Penick, Jr. 1898–1963. Trans Am Surg Assoc. 1963;81:435–436. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ochsner A. Frederick Amassa Coller, M.D. 1887–1964. Surgery. 1965;57((4)):630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ochsner A. Harold L. Foss, M.D. Bull Geisinger. 1968;20:12. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ochsner A., DeBakey M. Primary pulmonary malignancy; treatment by total pneumonectomy; analysis of 79 collected cases and presentation of 7 personal cases. SG&O. 1939;68:435–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ochsner A. Accuracy and reliability of medical records. Surgery. 1960;48((6)):1155–1156. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ochsner A. Influence of smoking on sexuality and pregnancy. Med Aspects Hum Sex. 1971;5:78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ochsner A. Care of the cancer patient after he returns home. JAMA. 1948;137:1582–1585. doi: 10.1001/jama.1948.82890520001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ochsner A. The time is now. Med Trib. 1969;10:48. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ochsner A. Present day surgical practice in the United States. Practitioner. 1948;160:145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ochsner A. The importance of psychiatry in surgery. Dig Neurol Psychiatiatr. 1950;18:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ochsner A. The value of health inventory. Americanos. 1957;1:5. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ochsner A. Surgical advances of the next twenty years. World Wide Abstracts. 1962;5:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ochsner A. Avoiding operative emergencies. Hosp Med. 1969;5:6–15. [Google Scholar]