Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea is an underrecognized and underdiagnosed medical condition, with a myriad of negative consequences on patients' health and society as a whole. Symptoms include daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, and restless sleep. While the “gold standard” of diagnosis is by polysomnography, a detailed history and focused physical examination may help uncover previously undiagnosed cases. Undetected obstructive sleep apnea can lead to hypertension, heart disease, depression, and even death. Several modalities exist for treating obstructive sleep apnea, including continuous positive airway pressure, oral appliances, and several surgical procedures. However, conservative approaches, such as weight loss and alcohol and tobacco cessation, are also strongly encouraged in the patient with obstructive sleep apnea. With increased awareness, both the medical community and society as a whole can begin to address this disease and help relieve the negative sequelae that result from it.

Keywords: Apnea, continuous positive airway pressure, polysomnography, snoring, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

Ochsner Main Campus: Sleep Medicine.

Sleep studies are available at the Ochsner Sleep Center on the Main Campus: a fully accredited 8-bed sleep laboratory open 7 nights a week. A sleep study can be facilitated through the Ochsner Sleep Center or ordered directly by a referring provider. All sleep study requests are screened by a certified sleep physician, and additional diagnostic elements—such as a parasomnia montage, electroencephalography, and transcutaneous CO2 monitoring—may be included in the testing. All elements of testing comply with the standards set by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Testing is also available at our Baton Rouge and North Shore locations.

Ochsner's Main Campus Sleep Center now has three specialty-trained sleep physicians readily available for referrals and consultations. They provide evaluations for all sleep-related symptoms and sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea, narcolepsy, restless legs syndrome, and insomnia); self-referrals are also welcome. The evaluation for suspected obstructive sleep apnea involves a thorough history, including medical comorbidities, and a focused upper airway examination for sources of potential obstruction. Patients are provided an in-depth review of sleep study results, and a treatment plan is tailored specifically to their needs. Ochsner sleep physicians have expertise in managing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel, and AutoPAP machines. The Ochsner Clinic also maintains a wide range of masks and equipment for patients to handle and even try. CPAP setup is facilitated with a wide range of home health companies, including Ochsner Durable Medical Equipment. Ochsner's goal is to provide the best quality of sleep care to patients as well as to support community health providers in caring for their patients' needs.

Sleep laboratory requests can be ordered directly into the Ochsner Clinical Workstation, and Sleep Center appointments can be made through Mainframe. For more information, the Ochsner sleep physicians can be contacted at 504-842-6860. Main Campus sleep physicians include Stuart Busby, MD, Katherine Smith, MD, and Elizabeth Bouldin, MD. The Main Campus clinic is located just inside the front entrance on the ground floor, at 1514 Jefferson Hwy., New Orleans, LA 70121.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is defined as the occurrence of at least 5 episodes per hour of sleep during which respiration temporarily ceases.1 Although OSA is a relatively common medical condition, it is believed that more than 85% of patients with clinically significant OSA have never been diagnosed.2 This is thought to reflect the fact that many patients with symptoms of OSA are not aware of their heavy snoring and nocturnal arousals.3 The cardinal features of OSA include signs of disturbed sleep such as snoring and restlessness, interruptions of regular respiratory patterns during sleep, and daytime symptoms such as fatigue or trouble concentrating that are attributable to disrupted sleep patterns at night.

It is estimated that as many as 1 of 5 adults has at least mild symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea, while 1 of 15 has moderate to severe symptoms.4 Although extensive studies have not been conducted that analyze the variability of OSA incidence by race, data support the fact that the prevalence of OSA is as high, if not higher, among African Americans as it is among Caucasians.4-6 Prevalence tends to be lower among people of Asian descent.7 Most population-based studies support the existence of a twofold to threefold greater risk of OSA in men than in women.8 Patients aged 65 through 95 years are also at significantly increased risk of developing symptoms.6,9 With the continuous rise in average life expectancies seen in Western countries, OSA is sure to pose a significant health challenge in years to come.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

OSA is caused by repetitive bouts of upper airway obstruction during sleep as a result of the narrowing of respiratory passages.3 The most common site of obstruction is the nasopharynx.10 It is important to differentiate OSA from the less common central sleep apnea, which is caused by an imbalance in the brain's respiratory control centers during sleep. While the pathogenesis of OSA is thought to be multifactorial, anatomic defects are thought to play a major role.3

Certain physical characteristics that may contribute to OSA include obesity, thickened lateral pharyngeal walls, nasal congestion, enlarged uvula, facial malformations, micrognathia, macroglossia, and tonsillar hypertrophy.1-3,10 Obesity contributes to airway narrowing through fatty infiltration of the tongue, soft palate, or other areas surrounding the airway.11

As the patient falls asleep, muscles of the nasopharynx begin to relax and the surrounding tissue collapses, causing compromise of the airway.3,12,13 As oxygen levels in the body start to drop and carbon dioxide levels rise, the patient is aroused from sleep; this causes an increase in sympathetic tone and subsequent contraction of nasopharyngeal tissue, which allows alleviation of the obstruction.2 Upon the patient's falling back to sleep, however, the airway is again subjected to narrowing until the patient is aroused from sleep once again. The cycle continues throughout the night, causing decreased time spent in rapid eye movement sleep and an overall decrease in quality of sleep.3,12-14 Because of the gravity-dependent factors discussed above, most obstructive symptoms happen in the supine position.15

Contributing to the anatomic causes of this disorder is a well-defined neural component. Several studies have confirmed that natural responses to negative pharyngeal pressure are already diminished during sleep.12,16 Furthermore, sleep disruption itself can lead to a further reduction in upper airway muscle activation, causing exacerbation of the aforementioned symptoms.17

Several studies have also explored the effects of repetitive short cycles of oxygen saturation that are followed by rapid reoxygenation. Periods of hypoxemia inhibit synthesis of nitrous oxide, a potent vasodilator, directly influencing vascular beds. Furthermore, episodes of hypoxia cause activation of various inflammatory cells that are potentially damaging to endothelial cells and predispose patients to the development of atherosclerotic lesions.2,18

RISK FACTORS

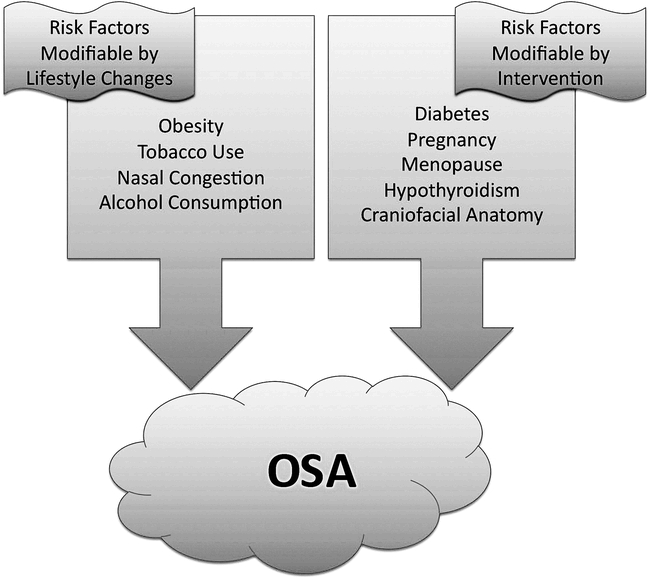

Several factors place patients at increased risk for developing OSA. Genetic factors affecting craniofacial anatomy have been linked with increased risk and severity of disease. Although many subtle hard and soft tissue factors (mandibular positioning, abnormal soft palate, tonsillar hypertrophy) can increase a patient's vulnerability for OSA,19 short mandibular body length seems to have the strongest association with disease.20 Other risks associated with OSA include nasal congestion, pregnancy, menopause, hypothyroidism, and diabetes. OSA is 3 times more prevalent in patients with insulin resistance than it is in the general population (Figure).21

Figure. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Social factors also play an important role in the development of OSA. Alcohol and tobacco use have strong associations with the development and progression of obstructive symptoms.19 Alcohol, as well as benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants, preferentially inhibit upper airway muscle activity while also depressing the respiratory centers of the brain. Tobacco use alone causes a threefold increase in risk of OSA, as observed in smokers compared to nonsmokers.22

While the conditions discussed above are all known risk factors for OSA, the most widely accepted and researched risk factor is obesity. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study showed that a 1 standard deviation increase in any measure of body habitus is associated with a fourfold increase in OSA disease risk.19 Excess body weight has been associated with acceleration of OSA, with a reduced time course of progression to moderate or severe disease.19

Obstructive sleep apnea itself can serve as a risk factor for the progression of other disease processes and should therefore receive careful attention by physicians. One study2 showed that patients with OSA are more likely to develop higher rates of hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, stroke, and even death.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS

A thorough history and physical examination will often elucidate some of the signs and symptoms of OSA. Common symptoms include snoring, awakening from sleep with a sense of choking, morning headaches, fitful sleep, decreased libido, as well as a history of hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, diabetes, or gastroesophageal reflux disease.23 Despite being a defining feature of OSA, alleged absence of daytime somnolence is not sufficient to dismiss the diagnosis of OSA, as often somnolence may go unnoticed or be underestimated because of its chronicity. Because of the nonspecific and variable features of OSA, its diagnosis based on a clinician's subjective analysis alone is inaccurate.24

OSA can be measured by using an apnea-hypopnea index, which records the number of times per hour of sleep that a patient experiences an abnormally low respiratory rate or complete cessation of breathing.9 Typically, an apnea-hypopnea index of 5 or more is sufficient for a diagnosis of OSA. Polysomnography, also known as a “sleep study,” is the current “gold-standard” of OSA diagnostic testing. In polysomnography, the patient is kept overnight and is monitored for several physiologic variables in a sleep laboratory. Variables monitored include body position, limb movement, oxygen saturation, cardiac rhythm and rate, respiratory effort, brain activity, eye movements, and stages of sleep.25 While a positive polysomnography study result reinforces a previous clinical diagnosis of OSA, current literature dictates that a negative polysomnography result, with strong clinical suspicion of OSA, does not rule out the disease because of the high levels of variability, technician error, and lack of standardization involved in testing.26 Additional diagnostic modalities for OSA include portable sleep monitors, radiographic studies for anatomic analysis, and empiric treatment.27 It is important to remember that OSA can occur and progress over relatively short periods of time, and its association with significant morbidity, coupled with the relatively low risk and high reward of therapy, merits a thorough workup and treatment plan.9

MANAGEMENT

Treatment of OSA depends on the severity, duration, and cause of the patient's symptoms as well as the patient's lifestyle, comorbidities, and overall health.28 Nonetheless, certain measures should be undertaken by nearly all persons affected by OSA. Overweight patients should be encouraged to undergo a weight-loss regimen. Studies25,29 have shown that a 10% weight loss is associated with a 26% reduction in apnea-hypopnea index scores. For severely obese patients, bariatric surgery (ie, gastric banding, gastric bypass, gastroplasty) may be considered, as studies30 have shown that symptoms of OSA can be relieved in up to 86% of patients undergoing such operations.

Other lifestyle changes that may help modify the signs and symptoms of OSA include cessation of alcohol and tobacco use, as well as the use of a lateral sleeping position.25,28 Furthermore, the use of benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants should be avoided.

Despite their proven efficacy, conservative approaches for treating OSA often fall short in providing clinically significant results. Treatment of OSA reduces health care utilization, medical costs, and even mortality.31-33 Therefore, patients should not shy away from therapeutic options, and medical practitioners should not hesitate to implement treatment regimens in addressing the problem of OSA.

First-line therapy for most patients with OSA continues to be the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). This therapy maintains adequate airway patency; it not only immediately reverses apnea and hypopnea, but it also decreases somnolence and increases quality of life, alertness, and mood.25,28 However, patient compliance levels average only 50% to 60% because of the frustrations associated with CPAP machines, including mask leaks, nasal congestion, and sleep disruption. More advanced machines such as the bilevel positive airway pressure and automatic positive airway pressure variants remain experimental, as they are more expensive and are not covered by most insurance plans for treatment of OSA.

A commonly implemented alternative to CPAP involves the use of oral appliances designed to advance the mandible forward. Such devices decrease arousal and the apnea-hypopnea index while increasing arterial oxygen saturation.34 Furthermore, patients tend to have a stronger preference for oral appliances.35 Many clinicians, however, still consider oral appliances to be a suboptimal alternative to CPAP.25

For those patients receiving little benefit from CPAP or oral appliances, surgery may be considered. The most commonly implemented surgical procedure for treatment of OSA is uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, where the palatine tonsils, as well as uvula and posterior palate, are resected and tonsillar pillars are reoriented in hopes of establishing a larger airway.25 The small number of trials conducted with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty measure the overall effectiveness of the procedure at around 50%. Because the procedure has been associated with complications such as postoperative pain, bleeding, nasopharyngeal stenosis, and vocal changes, patients may explore other surgical options.25,35 Other techniques used include laser-assisted uvuloplasty, tonsillectomy, hyoid suspension, partial resection of the tongue base, and maxillomandibular advancement.25 While laser-assisted uvuloplasty is the least invasive of the procedures listed, studies investigating the effectiveness of the more invasive maxillomandibular advancement have been promising, with success rates between 75% and 100%.36 Nasal surgery may be recommended when nasal obstruction or congestion is thought to be the major cause of symptoms.25,28,36 Tracheotomy is the definitive form of treatment for patients with severe life-threatening sleep apnea who are unresponsive to other treatment options.28

CONCLUSION

OSA is an important public health concern. While only 1 in 5 patients has at least mild OSA and only 1 in 15 has moderate to severe OSA, the societal impacts are often much greater. Disturbed sleep patterns lead to increased levels of daytime somnolence, which can cause days of missed work and increased levels of motor vehicle and occupational accidents. Furthermore, as discussed above, OSA can both worsen existing medical conditions and influence the onset of new disease. It is estimated that untreated OSA adds approximately $3.4 billion annually to health care costs in the United States.33 Given that the condition is undiagnosed for 85% of patients with sleep apnea, it is important for clinicians and patients alike to recognize and deal with the early signs and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea.

REFERENCES

- Basner R. C. Continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1751–1758. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct066953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Adachi T., Koshino Y., Somers V. K. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Circ J. 2009;73(8):1363–1370. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor L. D. Obstructive sleep apnea. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(8):2279–2286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T., Peppard P. E., Gottlieb D. J. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1217–1239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S., Klauber M. R., Stepnowsky C., Estline E., Chinn A., Fell R. Sleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):1946–1949. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline S. Epidemiology of sleep-disordered breathing. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;19(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ip M. S. M., Lam B., Mok Y. W., Ip T. Y., Lam W. K. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in middle-aged Chinese women in Hong Kong. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:A636. [Google Scholar]

- Strohl K., Redline S. Recognition of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(2 Pt 1):274–289. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T., Shahar E., Nieto F. J., et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(8):893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D. L., Launois S. H., Isono S., Feroah T. R., Whitelaw W. A., Remmers J. E. Pharyngeal narrowing and closing pressures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148(3):606–611. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter W. C., Gampper T., Gay S. B., Suratt P. M. Enlargement of the lateral pharyngeal fat pad space in pigs increases upper airway resistance. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79(3):726–731. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R. L., Mohiaddin R. H., Lowell D. G., et al. Sites and sizes of fat deposits around the pharynx in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea and weight matched controls. Eur Respir J. 1989;2(7):13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe A. A., Ono T., Ferguson K. A., Pae E. K., Ryan C. F., Fleetham J. A. Cephalometric comparisons of craniofacial and upper airway structure by skeletal subtype and gender in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110(6):653–664. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)80043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangel D. J., Mezzanotte W. S., Sandberg E. J., White D. P. Influences of NREM sleep on the activity of tonic vs. inspiratory phasic muscles in normal men. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73(3):1058–1066. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.3.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. E., Marshall I., Douglas N. J. The effect of posture on airway caliber with the sleep-apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(2):721–724. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel R. B., Trinder J., Malhotra A., et al. Within-breath control of genioglossal muscle activation in humans: effect of sleep-wake state. J Physiol. 2003;550(Pt 3):899–910. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.038810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgel D. W., Harasick T. Fluctuation in timing of upper airway and chest wall inspiratory muscle activity in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69(2):443–450. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S., Taylor C. T., McNicholas W. T. Selective activation of inflammatory pathways by intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2660–2667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.556746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjabi N. M. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):136–143. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles P. G., Vig P. S., Weyant R. J., Forrest T. D., Rockette H. E., Jr Craniofacial structure and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome—a qualitative analysis and meta-analysis of the literature. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;109(2):163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson K., Ayas N. T. The public health and safety consequences of sleep disorders. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85(1):179–183. doi: 10.1139/y06-095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter D. W., Young T. B., Bidwell T. R., Badr M. S., Palta M. Smoking as a risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(19):2219–2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervin R. D. Sleepiness, fatigue, tiredness, and lack of energy in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118(2):372–379. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner S., Szalai J., Hoffstein V. Is history and physical examination a good screening test for sleep apnea? Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):356–359. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemons W. W. Obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):498–504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber C., O'Brien C., Schluter J., Davies S., Leatherman J., Mahowald M. Single night studies in obstructive apnea. Sleep. 1991;14(5):383–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn O., Brack T., Russi E. W., Bloch K. E. A continuous positive airway pressure trial as a novel approach to the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2006;129(1):67–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips B., Kryger M. H. Management of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: overview. In: Kryger M. H., Roth T., Dement W. C., editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2005. pp. 1109–1121. 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Peppard P. E., Young T., Palta M., et al. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disoriented breathing. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3015–3021. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald H., Avidor Y., Braunwald E., et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. Erratum in: JAMA. 2005;293(14):1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Rodriguez F., Peña-Griñan N., Reyes-Nuñez N., et al. Mortality in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea patients treated with positive airway pressure. Chest. 2005;128(2):624–633. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahammam A., Delaive K., Ronald J., Manfreda J., Roos L., Kryger M. H. Health care utilization in males with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome two years after diagnosis and treatment. Sleep. 1999;22(6):740–747. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur V., Blough D. K., Sandblom R. E., et al. The medical cost of undiagnosed sleep apnea. Sleep. 1999;22(5):749–755. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotsopoulos H., Chen C., Qian J., Cistulli P. A. Oral appliance therapy improves symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:743–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-208OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles T. L., Lasserson T. J., Smith B., White J., Wright J. J., Cates C. J. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006. p. CD001106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wilhelmsson B., Tegelberg A., Walker-Engstrom M. L., et al. A prospective randomized study of a dental appliance compared with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119(4):503–509. doi: 10.1080/00016489950181071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]