Abstract

Physician reimbursement and the coding to support it are critically important to the sustained health of any physician's practice. This article reviews the recent history of physician reimbursement from the government and third-party payers and physician coding to support reimbursement. Explanations of terminology and documentation requirements are included.

Keywords: Reimbursement, Billing, CPT, ICD-9

Understanding physician reimbursement is critically important to the sustained health of any physician's practice. Reimbursement involves more than just what you get paid; it is a long, and often convoluted, process that starts when a patient first contacts your office (1). In order to appropriately maximize your reimbursement, it is imperative that you know the basics. This includes correct coding. The key to begin to understand this aspect of the business of medicine is to understand the basics of Medicare. While private payers vary in their reimbursement rates and policies, most are tied in some form to the Medicare system.

PHYSICIAN REIMBURSEMENT

Physician reimbursement from Medicare is a three-step process: 1) appropriate coding of the service provided by utilizing current procedural terminology (CPT®); 2) appropriate coding of the diagnosis using ICD-9 code; and 3) the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) determination of the appropriate fee based on the resources-based relative value scale (RBRVS).

CPT® is a proprietary product of the American Medical Association (AMA). CPT® is a uniform coding system that was developed in conjunction between physicians and the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), and was first published by the AMA in 1966. The initial purpose of the system was to help standardize terminology among physicians and to serve as a shorthand that would simplify medical records for physicians and record clerks. Since 1970, CPT® has undergone yearly updates based on changes in medical and surgical procedures and the development of new technology. For a new procedure or technology to receive a code, it must first meet criteria: It must be done by a reasonable number of the specialty that presents the code, be performed at reasonable frequency, be done throughout the country, and have peer-reviewed literature supporting its efficacy. It is important to remember that each CPT®code represents the typical patient. CPT® also uses a series of modifiers in addition to the original code to better describe the service provided. This allows not only for better data collection regarding the frequency and complexity of services, but also for appropriate reimbursement by Medicare.

Once a procedure or service receives a code, it needs to be valued for reimbursement purposes. Prior to 1992, physicians were reimbursed based on “usual, customary, and reasonable charges” (UCR). UCRs were based on the physician's most frequent charge for the service (usual), the average charge for that service in the area (customary), and the actual charge for the service (reasonable) (2). Individuals within the federal government, private insurers, and non-procedure-based medical specialties felt that this system perpetuated rising health care costs and inequities in medical care. These individuals believed that this system served as an incentive for physicians to inflate charges, even in those instances where actual costs were decreasing, and to continue the inequities in fees between proceduralists and non-proceduralists. In response to this, the federal government instituted the Medicare fee schedule, and Medicare implemented the RBRVS in 1992.

The Medicare fee schedule was based on the work of a research team led by William Hsiao, a Har-vard economist under contract to CMS (3–5). The Harvard study ranked procedures and services relative to each other based on the amount of physician work necessary to perform the procedure or service. Work was defined as a combination of the time used to perform the service and the complexity of the service (mental effort, knowledge, judgment and diagnostic acumen, technical skill, physical skill, psychological stress, and potential iatrogenic risk) (6). Work was then broken down into three time periods: pre-service, intra-service, and post-service.

Pre-service work for surgical procedures has come to be defined as the physician work provided from the day before, until the time of the operative procedure (i.e., skin incision). This may involve any or all of the following: hospital admission work-up; the preoperative evaluation, including the procedural work-up; review of records; communicating with other professionals, patient and family; obtaining consent; dressing, scrubbing, and waiting before the operative procedure; preparing patient and needed equipment for the operative procedure; and positioning the patient and other non “skin-to-skin” work done in the operating room prior to incision. Pre-service work does not include the consultation or evaluation at which the decision to provide the procedure was made.

Intra-service work includes all “skin-to-skin” work that is a necessary part of the procedure. The time measurement for the intra-service work is from the start of the skin incision until the incision is closed.

Unlike pre-service work, post-service work varies depending on the magnitude of the procedure. In an effort to accurately assign the amount of post-procedure work, specific CPT® codes have been assigned specific global periods. There are currently three post-procedural global periods: 0 days, 10 days and 90 days. Routine post-procedure care includes physician work following skin closure that is done on the day of the procedure, including non-“skin-to-skin” work in the OR. This includes patient stabilization in the recovery room, communicating with the patient and other professionals (including written and telephone reports and orders), and patient visits on the day of the procedure. For a surgical service with a global period of 10 or 90 days, the post-service work includes all of the above, as well as postoperative hospital care, including the intensive care unit if needed; other inhospital visits; discharge day management services; and office visits within the assigned global period of 10 or 90 days (7).

For non-surgical services such as office evaluation and management (E & M), the pre-service work includes preparing to see the patient, reviewing records, and communicating with other professionals. The intra-service work includes the work provided while the physician is with the patient and/or family. This includes the time in which the physician obtains the history, performs a physical evaluation, and counsels the patient. The post-service work for non-procedural services includes arranging for further services; reviewing results of studies; and communicating further with the patient, family, and other professionals, including written and telephone reports as well as calls to the patient.

While the study by Hsiao and colleagues initially valued only 200 codes and ranked them according to physician work (4), the Relative Value Update Committee (RUC) subsequently valued and ranked each CPT® code relative to other codes. New codes were valued using provider surveys to obtain an appropriate work value. These surveys allow for individuals who perform the procedures to value pre-, intra-, and post-service work relative to established codes. According to federal law, the relative value of codes is reviewed every 5 years by the RUC, allowing for corrections in the relativity of the codes. Currently, physician work is not the only value used to calculate a Relative Value Unit (RVU).

While the Work RVUs (wRVUs) make up the majority of the total RVUs (tRVUs) for a specific CPT® code, RVUs are also calculated for practice expense (peRVU) and malpractice expense (mRVU) for each code. Similar to wRVUs, peRVUs are calculated based on the amount of resources used in the pre-, intra- and post-service time. This includes not only the nursing and ancillary staff key to the procedure or service, but also supplies used during the pre- and post-procedure period. If the procedure is performed in the office, intra-service personnel and supplies are included. For procedures done in a facility (usually a hospital) these costs are reimbursed based on the DRG (Part A), and are paid to the health care facility, not to the physician. Malpractice Expense RVUs are calculated from actual malpractice premium data obtained throughout the country. Using previous CMS claims, a value for each CPT® code is determined based on a risk factor for the dominant specialty that provides service (8).

Final physician reimbursement by CMS is then multiplied by a geographic practice cost index (GPCI), which is intended to adjust payments for differences in physician practice costs across geographic areas. For a given service, multiplying the service-specific Physician Work, Practice Expense, and Malpractice Expense RVUs by their respective GPCIs determines the payment amount in a given geographic area. Next, these three products are added, yielding a geographically adjusted RVU total for the service. This number is then converted to dollars by a conversion factor, which in 2006 was $37.8975 per RVU and currently is stable for 2007. As an example, in 2004, for CPT® code 44140 (Colectomy, partial; with anastamosis) ((wRVU * wGPCI) + (peRVU * peGPCI)+ (mRVU * mGPCI)}* 37.8975 = $ CMS reimbursement. The amount paid varies by region:

San Francisco, CA

(20.97 wRVU * 1.068 wGPCI) + (8.69 peRVU * 1.458 peGPCI) + (2.58 mRVU * 0.669 mGPCI) * 37.8975 = $1394.33

Boston, MA

(20.97 wRVU * 1.041 wGPCI) + (8.69 peRVU * 1.239 peGPCI) + (2.58 mRVU * 0.803 mGPCI) * 37.8975 = $1313.85

New Orleans, LA

(20.97 wRVU * 1.0 wGPCI) + (8.69 peRVU * 0.945 peGPCI) + (2.58 mRVU * 1.240 mGPCI) * 37.8975 = $1227.17

Little Rock, AR

(20.97 wRVU * 1.000 wGPCI) + (8.69 peRVU * 0.847 peGPCI) + (2.58 mRVU * 0.389 mGPCI) * 37.8975 = $ 1111.69

While Medicare is an extremely large and, at times, unwieldy way to manage healthcare and healthcare-related costs, understanding it is key to understanding both hospital and physician reimbursement by private payers. Most private payers today use CPT® codes to identify physician services. While private payers do not have to follow the rules set forth by the federal government (for instance, they often do not recognize surgical modifiers), they find that CPT® is a well-established and familiar system allowing for correct physician coding. Private payers in non-capitated contracts often set reimbursement based on a percentage of the Medicare fee schedule. The percentage reimbursement will often vary by region. The larger payers have taken this one step further, using Medicare to develop their own fee schedule. Again using CPT® terminology, companies will adjust payment based on the individual service provided: for example, paying E&M codes 105%, office based procedures 110%, and surgical procedures 115% of Medicare. This is often modified regionally based on the rules of supply and demand. In areas with a paucity of a specific specialty, reimbursement is high, as opposed to a saturated market where the insurance company can play one physician or group against another to obtain a favorable contract.

E & M CODING

Physicians can bill or code for a number of different types of patient encounters. The most common non-procedural encounters are evaluation and management services, or E & M, codes and include outpatient activities such as office/outpatient visits, outpatient consultations, inpatient hospital visits, inpatient consultations, and management of patients in observation or critical case status (1).

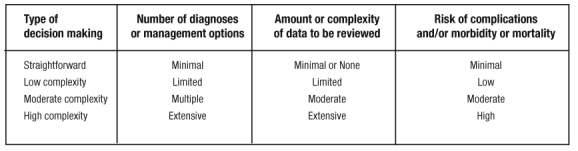

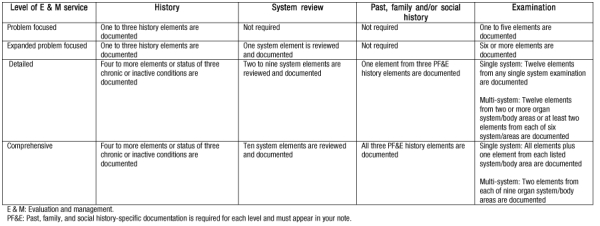

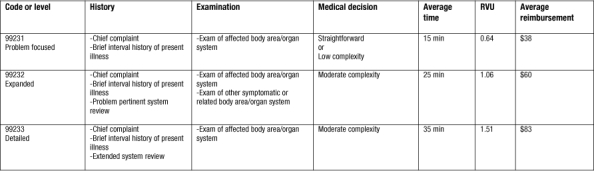

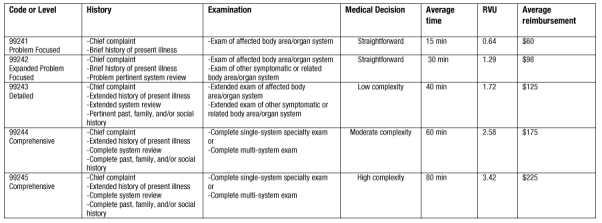

The different levels of E & M codes are determined based on the history, examination, and medical decision making. Medical decision making refers to the complexity of establishing a diagnosis and/or selecting a management option. This component should be documented in the Plan portion of your prognosis note. The types of medical decision making (Table 1) include straightforward, low, moderate, or high complexity. Straightforward is one self-limited or minor problem such as a cold, insect bite, or sore throat. Low complexity is two or more self-limited or minor problems or one stable chronic illness, such as well-controlled hypertension or non-insulin dependent diabetes, cataract, benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), or an acute uncomplicated illness or injury such as cystitis, allergic rhinitis, or simple sprain. Moderate complexity is one or more chronic illnesses with mild exacerbation or progression or side effects of treatment, or two or more stable chronic illnesses or undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis, e.g., a lump in the breast; an acute illness with systemic symptoms such as pyelonephritis, pneumonitis, or colitis; or acute complicated injury such as head injury with a brief loss of consciousness. High complexity is one or more chronic illnesses with severe exacerbation or progression or side effects of treatment, or acute or chronic illnesses or injuries that pose a threat to life or body function, e.g., multiple trauma; acute myocardial infarct; pulmonary embolism; acute renal failure; or psychiatric illness with potential to hurt self or others (Tables 2–4). Also included in medical decision making is the use of adjunct testing. As expected, the invasiveness and potential for morbidity associated with a test increase per E & M level, from blood tests and chest X-ray to cardiac catheterization and endoscopy on the upper end.

Table 1.

Medical decision making.

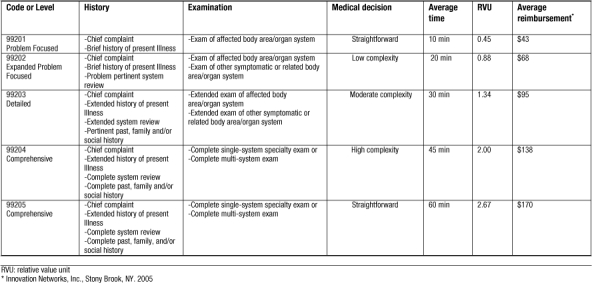

Table 2.

Office/outpatient visits: new patient.

Medicare also utilizes additional E & M guidelines for teaching physicians. Teaching (billing) physicians must document that they were physically present and participating during the key component of the service rendered, verify pertinent findings in the resident's notes, and personally document modifications or enhancements to the resident's notes. This can be at the end of the resident's note or in a separate progress note. If the resident performs a minor procedure such as suturing, the teaching physician must be physically present during the entire procedure and document his or her presence in order to bill for the service. Medical students are allowed to document only the history component of any service. The teaching physician must perform the examination and provide decision making.

Coding for services differentiates whether the patient is a new or established patient to the physician completing the code. A new patient is one who has not received any professional services from the physician, or another physician of the same specialty who has belonged to the same group practice within the past three years. For new patients, documentation of all three key components is required (Table 5).

Table 5.

Medicare's required documentation components.

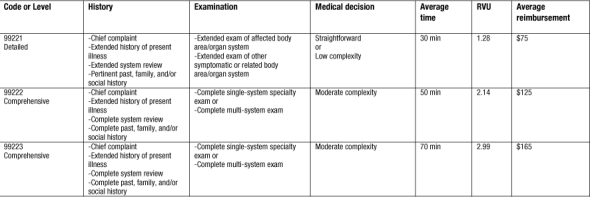

A consultation is a service provided by a physician whose opinion or advice regarding evaluation and/ or management of a specific problem is required by another physician or other appropriate source. Services are provided in the physician's office or in an outpatient or other ambulatory facility, including hospital observation services. A request in the form of a consultation note from the attending physician must be documented in the medical record and communicated to the requesting physician or other appropriate source.

The history component of an E & M service describes the development of the patient's present illness from the first signs and symptoms, or from the previous encounter, to the present. Elements include location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms.

System review is an inventory of body symptoms obtained through a series of questions. Elements include cardiovascular, respiratory, eyes, ears, nose, throat, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, integumentary, neurological, psychiatric, endocrine, hematologic, lymphatic, allergic, immunologic, and constitutional (vital signs, general appearance).

Past history includes the patient's past experience with illness, operations, injuries, and treatments. Family history is a review of medical events in the patient's family, including diseases that may be hereditary or place the patient at risk. Social history is an age-appropriate review of past and current activities and habits (Tables 6,7).

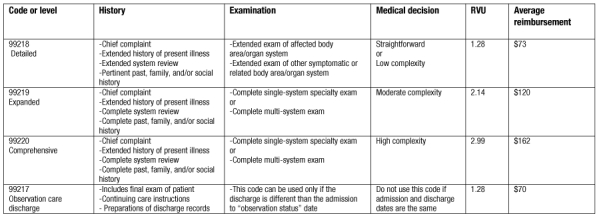

Table 6.

Initial inpatient hospital visits: new or established patient.

Table 7.

Subsequent inpatient hospital visits: new or established patient.

Physical examination utilizes the following body areas: cardiovascular, respiratory, eyes, ears, nose, throat, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, skin, neurologic, psychiatric, hematologic, lymphatic, immunologic, and constitutional. Specific abnormal and relevant negative findings of the examination of the affected or symptomatic body area or organ system must be documented in the note. A notation of “abnormal” is insufficient without additional clarification. Abnormal or unexpected findings of the examination of an unaffected or asymptomatic body area or organ system should be described. A brief notation indicating “normal” or “negative” is insufficient to document normal findings related to unaffected body areas or asymptomatic organ systems. If an organ system or body area is deferred during a specific portion of the examination, such as a pelvic or rectal exam, you must document “deferred” and the reason it was deferred. Simply noting “deferred” is not enough.

Observation care codes (Table 8) are used to report encounters with the patient by the admitting physician. The patient is designated as “observational status” by the hospital. These codes are used per day with admission and discharge dates that are different. Do not use these codes for post-operative recovery. Documentation of all three key components is required.

Table 8.

Observation care visits: new or established patient.

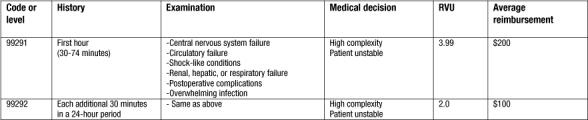

Critical care codes (Table 9) are used to report the total duration of time spent by a physician providing constant attention to an unstable critically ill patient, or an unstable critically injured patient, even if the time spent by the physician providing critical care services on that date is not continuous (the physician need not be constantly at bedside per se, but must be engaged in physician work directly related to the individual patient's care). The total time spent must be documented in the patient's medical record. Services included in critical care are interpretation of cardiac output measurements, chest X-rays, blood gases, gastric intubation, temporary transcutaneous pacing, ventilator management, vascular access procedures, or information data stored in computers (ECGs, blood pressures, hematologic data).

Table 9.

Critical care visits: new or established patient.

Knowledge of physician reimbursement and coding is critical to maximizing practice income while avoiding the potential for fraud. While the process may be convoluted and cumbersome, each provider must spend the time to understand the system. This article has attempted to provide basic information that will hopefully serve as a stimulant for further learning.

Table 3.

Office/outpatient visits: established patient.

Table 4.

Office/outpatient consultation visits: new or established patient.

REFERENCES

- Margolin D. Health care economics. 2006. pp. 727–734. In: Wolff BG, Fleshman JW, Beck DE, Pemberton JH, Wexner SD, eds. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Blount L. L., Waters J. M., Gold R. S. Methods of insurance reimbursement. 2001. pp. 6–7. In Blount LL, Waters JM, eds. Mastering the Reimbursement Process. Chicago: AMA Press.

- Hsiao W. C., Braun P., Dunn D., Becker E. R. Resource-based relative values. An overview. JAMA. 1988;260:2347–2353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao W. C., Couch N. P., Causino N., Becker E. R., Ketcham T. R., Verrilli D. K. Resource-based relative values for invasive procedures performed by eight surgical specialties. JAMA. 1988;260:2418–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao W. C., Yntema D. B., Braun P., Dunn D., Spencer C. Measurement and analysis of intraservice work. JAMA. 1988;260:2361–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao W. C., Braun P., Becker E. R., Thomas S. R. The resource-based relative value scale. Toward the development of an alternative physician payment system. JAMA. 1987;258:799–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry C. RUC Research Subcommittee. The use of intensity measures in the development of physician work relative value units (RVUs) January 14, 2004. Unpublished monograph presented at the AMA Relative Value Update Committee Annual Meeting, Scottsdale, AZ.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. “Physician Fee Schedule Overview.” 26 December 2006. Available: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/. Accessed 26 January 2007.