Abstract

Siah proteins function as E3 ubiquitin ligase enzymes to target the degradation of diverse protein substrates. To characterize the physiological roles of Siah2, we have generated and analyzed Siah2 mutant mice. In contrast to Siah1a knockout mice, which are growth retarded and exhibit defects in spermatogenesis, Siah2 mutant mice are fertile and largely phenotypically normal. While previous studies implicate Siah2 in the regulation of TRAF2, Vav1, OBF-1, and DCC, we find that a variety of responses mediated by these proteins are unaffected by loss of Siah2. However, we have identified an expansion of myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow of Siah2 mutant mice. Consistent with this, we show that Siah2 mutant bone marrow produces more osteoclasts in vitro than wild-type bone marrow. The observation that combined Siah2 and Siah1a mutation causes embryonic and neonatal lethality demonstrates that the highly homologous Siah proteins have partially overlapping functions in vivo.

Tagging proteins with polyubiquitin chains, termed ubiquitination, induces their proteolytic degradation via the proteasome. Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis functions as a rapid means of regulating cellular protein levels and is an important regulatory mechanism in diverse cellular processes. The RING domain-containing Siah (seven in absentia homologue) proteins are involved in selecting substrates for ubiquitination. Siah family proteins can mediate E3 ubiquitin ligase activity either through direct binding to substrates (17) or by functioning as the essential RING domain subunit of larger E3 complexes (26-28, 31, 47). To date, no other ubiquitin ligases that exhibit this dual function have been identified. Overexpression of Siah proteins induces the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of diverse protein substrates, including nuclear transcription factors (β-catenin and c-myb), a transcriptional coactivator (OBF-1), a corepressor (N-CoR), a cell surface receptor (DCC), cytoplasmic signal transduction molecules (TIEG-1, TRAF2, and Numb), an antiapoptotic protein (Bag-1), a microtubule motor protein (Kid), and a protein involved in synaptic vesicle function in neurons (synaptophysin) (4, 13, 17, 20, 21, 24, 28, 31, 42, 44, 48, 53, 56, 60). While these biochemical studies implicate the Siah proteins in numerous signaling pathways, the physiological relevance of these observations remains unclear.

Mice have three unlinked Siah genes—termed Siah1a, Siah1b, and Siah2 (8)—while humans have single SIAH1 and SIAH2 genes (19). Siah1a and Siah1b (collectively Siah1) encode 282-amino-acid proteins that differ from one another at only 6 amino acid residues (98% identical). Siah2 encodes a 325-amino-acid protein that, with the exception of a longer and divergent N-terminal region, is 85% identical to Siah1 proteins. Consistent with this high degree of homology, both Siah1a and Siah2 can target DCC for proteolytic degradation, suggesting that the Siah proteins may have overlapping functions (21). However, the observation that TRAF2 is degraded by Siah2, but not by Siah1a, demonstrates that some biochemical functions of the Siah proteins are unique to individual family members (17).

Siah2 has been implicated in the regulation of the activity of a number of molecules that control development and activation of the immune system. We previously demonstrated that the Siah proteins share structural similarity with TRAF proteins (36). TRAFs are a family of signaling adaptor proteins (TRAF1 to -6) that play important roles in innate and adaptive immunity by mediating signal transduction from a variety of receptors of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily and the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily (23). Overexpression of Siah2 induces the degradation of TRAF2 and inhibits TNF alpha (TNF-α)-induced NF-κB and Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) activation (17). Siah2 overexpression also inhibits signaling by Vav1 (14), a protein necessary for antigen receptor signaling in B and T cells (49, 61). Finally, Siah2 interacts with the B-cell-specific transcriptional coactivator OBF-1 (4).

In order to understand the physiological roles of the Siah protein family, we aim to generate mice with mutations in each of the Siah genes, singly and in combination. We have previously shown that Siah1a knockout mice exhibit severe growth retardation, frequently exhibit early lethality, and exhibit a block in meiotic cell division during meiosis I of spermatogenesis (9). In the present study we characterize hematopoiesis in Siah2 mutant mice and analyze signaling and cellular responses that are mediated by TRAF, Vav1, and OBF-1 proteins. In contrast to the deleterious effects of Siah1a mutation, mice lacking Siah2 are largely phenotypically normal. Combined mutation of Siah2 and Siah1a induces neonatal lethality, confirming the prediction that Siah proteins have partially overlapping functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

Unless otherwise stated, antibodies were from BD Pharmingen. The following anti-mouse antibodies were used in this study: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD28 (37.51), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), anti-Mac-1 (M1/70), anti-F4/80 (Caltag), and anti-immunoglobulin M (anti-IgM) (Fab′)2 fragments (ICN).

Generation of Siah2 mutant mice.

The Siah2 targeting construct was generated by insertion of a neomycin resistance gene cassette (NeoR) into the BamHI restriction site of a fragment of Siah2 genomic DNA (see Fig. 1A) isolated from a 129Sv genomic λ phage library (8). A thymidine kinase (TK) resistance gene cassette was inserted at the 5′ end of the targeting construct to allow for negative selection. Transfection of J1 embryonic stem (ES) cells (25) and selection of drug-resistant colonies was as previously described (9). Genomic DNA from resistant clones was digested with EcoRI, and Southern blots were probed with a 1-kb PCR fragment that lies 3′ of the region of DNA used in the targeting construct. Homologous recombination introduces a new EcoRI site, leading to a size shift of the hybridizing band from 13.2 to 3.7 kb. Four targeted clones were isolated from 400 clones screened. Several male chimeras (95 to 100% agouti coat color) were derived by injection of clone 8.4 targeted ES cells into C57BL/6J blastocysts. Two chimeras transmitted both agouti coat color and the targeted allele to progeny when mated to C57BL/6J mice. Analyses of homozygous mutant mice were performed on both the 129Sv genetic background and on mice whose genes had been backcrossed to the C57BL/6J background for 13 generations.

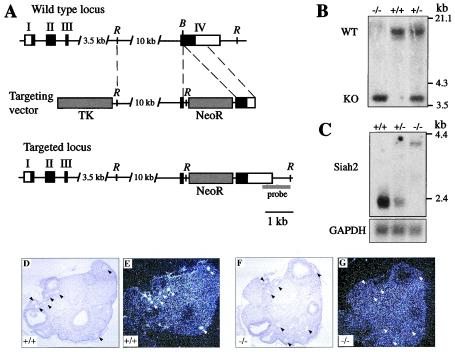

FIG. 1.

Disruption of Siah2 by gene targeting. (A) Exons I, II, III, and IV of Siah2 are depicted as rectangles, the coding region of Siah2 is shown in black, and untranslated regions are shown in white. The targeting construct containing a TK gene cassette and a neomycin resistance gene cassette (NeoR) is depicted. DNA fragments used as the left and right arms of homology are represented by dashed lines. Homologous recombination yields the targeted locus in which the NeoR cassette is inserted into exon IV and introduces a new EcoRI restriction site. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes: B, BamHI; R, EcoRI. (B) Southern blot genotyping of progeny derived from an intercross of Siah2 heterozygous mice. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and Southern blotted with a 1-kb probe located 3′ of the region of DNA used in the targeting construct (probe in panel A). The positions of the 13.2-kb wild-type (WT) and 3.7-kb knockout (KO) alleles are shown. The migration positions of known DNA molecular size markers are shown. (C) Northern blot analysis of 3 μg of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from brains of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous (−/−) Siah2 mutant mice. A 410-bp ScaI-DraI fragment derived from the 3′-untranslated region of exon IV of Siah2 was used as a probe. Probing with a fragment from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene served as a loading and transfer control. The migration positions of known RNA molecular size markers are shown. (D to G) Analysis of wild-type (D and E) and Siah2 mutant (F and G) ovaries by in situ hybridization using an antisense riboprobe derived from nucleotides 1159 to 1786 of the Siah2 cDNA. This probe includes the final 110 bp of the Siah2 coding region and extends into the 3′-untranslated region of exon IV. (D and F) Light-field illumination. Black triangles mark the positions of selected developing ovarian follicles. (E and G) Dark-field illumination. White triangles mark the positions of the selected developing ovarian follicles marked in panels D and F. Note the absence of Siah2 expression in ovaries from Siah2−/− mice.

Primary cell culture and proliferation assays.

Mouse embryo fibroblasts were generated and cultured as previously described (12).

Single-cell lymphocyte suspensions were prepared from spleen, thymus, or lymph nodes (mesenteric, inguinal, or axilliary) by crushing organs through a wire mesh and passing them through a 40-μm-pore-size cell strainer (Becton Dickinson). Red blood cells were removed from spleen suspensions by incubation for 5 min at room temperature in red cell lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 1 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 7.2]), followed by two washes in phosphate-buffered saline-2% fetal bovine serum (PBS-2% FBS). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 250 μM l-asparagine, 13 μM folic acid, penicillin (500 IU/ml), streptomycin (500 μg/ml) and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Cultures were initiated at starting cell densities of 2 × 106 splenocytes or lymphocytes/ml or 107 thymocytes/ml. Cultures were mitogenically stimulated by addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli 0111:B4; Sigma), anti-IgM (Fab′)2 fragments, or concanavalin A (ConA) (Sigma) by plating in wells that had been coated for several hours with anti-CD3 with or without anti-CD28 antibodies, or by plating in wells containing 3T3 fibroblasts expressing mCD40L (50) which had previously been cell cycle arrested by treatment with 30 Gy of gamma radiation (137Cs source; 0.75 Gy/min). For proliferation assays, cells were cultured in 200-μl volumes in 96-well plates. After 2 days, 1 μCi of [6-3H]thymidine (29 Ci/mmol; Amersham) was added for the final 16 h of culture before harvesting onto glass filter paper with several washes of water (Filtermate 196 Harvester; Packard). Incorporated radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting using Readysafe scintillant (Beckman-Coulter) and a Tri-carb 2100TR liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard).

Bone marrow macrophages (BMM) were obtained by flushing femurs with a 23-guage needle and culturing whole bone marrow preparations for 3 days at a starting density of 106 cells/ml in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 30% L-cell-conditioned medium (a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor [M-CSF], prepared as described in reference 43), penicillin (500 IU/ml), streptomycin (500 μg/ml), and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Nonadherent cells were removed and transferred to 96-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well, and BMM were grown to confluence over 5 days. Fresh medium was added on the third day. Cells were starved of M-CSF for 24 h by growth in the absence of L-cell-conditioned medium prior to restimulation with recombinant human CSF-1 (Chiron) with or without LPS (E. coli 0111:B4; Sigma), poly(I) · poly(C) (Calbiochem), recombinant mouse TNF-α (BD Pharmingen), or beta interferon (IFN-β) (BD Pharmingen). DNA synthesis was assessed by the addition of 1 μCi of[6-3H]thymidine for the final 8 h of culture. Cells were lysed by freeze-thawing three times, and incorporated radioactivity was quantitated as described above.

Osteoclasts were generated from bone marrow cells by culturing white blood cells at a starting density of 105 cells per well on a 48-well plate. Cells were grown in α-modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (500 IU/ml), streptomycin (500 μg/ml), and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-RANKL fusion protein (100 ng/ml; purified from a construct kindly provided by F. Patrick Ross, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Mo.) and human CSF-1 (20 ng/ml; Genetics Institute Inc.) were added to cultures to induce osteoclastogenesis. Cultures initiated with GST plus CSF-1 did not yield osteoclasts (data not shown). Fresh medium was added every 3 days. After 7 days, cells were fixed for 5 min at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed in a 1:1 mixture of acetone and methanol, and dried before TRAP staining (37). Osteoclasts were scored as TRAP+ multinuclear (more than three nuclei) cells.

Colony-forming cell assays.

For agar colony-forming assays, 5 × 104 whole bone marrow cells were cultured in 0.3% agar in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 20% FCS and either recombinant human granulocyte CSF (G-CSF) (1,000 U/ml; Amgen), recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) (1,000 U/ml; Peprotech), recombinant murine M-CSF (20 ng/ml; Peprotech), recombinant murine IL-3 (1,000 U/ml; Peprotech) or stem cell factor (SCF)(approximately 100 ng/ml, derived from BHK-SCF-conditioned medium [gift of S Collins, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Wash.]), and recombinant human G-CSF (1,000 U/ml). Colonies were counted after 7 days of culture. Agar colonies were fixed and floated onto glass slides, air dried, and stained with hematoxylin to allow differential counting of colony types. For methylcellulose colony-forming assays, 5 × 104 whole bone marrow cells were cultured in 3% methylcellulose supplemented with 20% FCS, recombinant murine IL-3 (1,000 U/ml; Peprotech), recombinant murine IL-6 (1,000 U/ml; Peprotech), SCF (as above), and recombinant murine erythropoietin (2 U/ml; Janssen-Cilag). Colonies were counted after 12 days of culture.

In vivo antibody responses.

Mice received intraperitoneal injections with 10 μg of (4-hydroxy-3-mitrophenyl)acetyl (NP)-LPS in PBS or 100 μg of NP-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) precipitated on alum as previously described (41). Serum samples from nonimmunized or immunized mice were obtained by eye bleeding. Clots were formed overnight at 4°C, and serum was recovered by centrifugation for 1 min at 15,700 × g in a microcentrifuge. Ninety-six-well enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates (Costar) were coated for 4 h at room temperature with NP20-bovine serum albumin (BSA) (15 μg/ml) (41) in PBS. Plates were washed with three washes each of (i) PBS containing a small amount of Tween 20, (ii) PBS, and then (iii) water. Serial dilutions of serum samples were incubated overnight at room temperature and washed as above, and anti-mouse IgG1 or IgM horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) was added for 4 h at room temperature. All serum and antibody incubations were conducted in block solution (PBS, 1% FBS, 0.05% Tween 20, 2% skim milk powder). Following a final series of washes, horseradish peroxidase was detected by incubation in the dark for 30 to 40 min at room temperature with 0.01% hydrogen peroxide and 2′2-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid) (0.54 mg/ml; Sigma) dissolved in 0.1 M citric acid (pH 4.4). Color development was quantitated by measurement of absorbance at 405 nm minus absorbance at 490 nm.

NF-κB and JNK assays.

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) stimulated with recombinant murine TNF-α (0.2 ng/ml; Promega) were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and harvested as described below for analysis of NF-κB DNA binding activity by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and for JNK activation by Western blotting.

Nuclear extracts for EMSA were prepared by incubating cells for 15 min on ice in cytoplasmic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, KOH [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, leupeptin [10 μg/ml], aprotinin [10 μg/ml], pepstatin [1 μg/ml], 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]), and this was followed by addition of NP-40 to 0.59% final concentration, vortexing, and spinning in a microcentrifuge at 15,700 × g. The nuclear pellet was extracted for 20 min on ice with frequent agitation in protein extraction buffer (420 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, leupeptin [10 μg/ml], aprotinin [10 μg/ml], pepstatin [1 μg/ml], 0.5 mM PMSF). Lysates were centrifuged in a microcentrifuge at 15,700 × g and 4°C for 10 min to remove insoluble material. Cleared protein lysates were quantitated using the Dc protein assay (Bio-Rad) using BSA as a standard. EMSA reactions were undertaken in a 15-μl total volume, comprising 5 μg of nuclear protein extract, 1 μl (1 × 104 to 3 × 104 cpm) of 32P-end-labeled κB3 probe (16), 1 μg of BSA, 1 μg of poly(dI:dC) (Sigma) and an appropriate volume of 5× NF-κB binding buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 25% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM dithiothreitol). The volume of 5× NF-κB binding buffer was calculated by assuming that the nuclear extract added to the reaction mixture represents a 1× contribution of binding buffer. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min and then run on a native 5% polyacrylamide-Tris-borate-EDTA gel at 200 V, before drying and autoradiography.

Lysates for analysis of JNK phosphorylation were prepared by lysis of cells on ice in JNK lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, leupeptin [10 μg/ml], aprotinin [10 μg/ml], pepstatin [1 μg/ml], 0.5 mM PMSF). Lysates were cleared and quantitated as described above, and 30 μg of protein extract was analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody that detects doubly phosphorylated (active) JNK (V793A; Promega).

Additional techniques.

In situ hybridization (7, 8), bone histomorphometry, and von Kossa staining (39), alizarin red-S and Alcian blue staining (32), motoneuron apoptosis assays (33), and hematopoietic reconstitution (12) were all performed as described in the indicated references.

RESULTS

Generation of Siah2-null mice.

We generated a targeting vector designed to inactivate the Siah2 gene by way of insertion of a neomycin resistance gene cassette (NeoR) into exon IV (Fig. 1A). This insertion is predicted to truncate the Siah2 protein at amino acid residue 180. As truncating mutations in Drosophila sina (at positions equivalent to amino acids 219 and 221 in mouse Siah2) generate null alleles (6), homologous recombination is expected to abolish Siah2 function. We screened J1 ES cells (25) using a positive (neomycin resistance) and negative (TK) selection strategy to enrich for homologous recombinant ES cell clones. Of 400 clones screened by Southern blotting, 4 clones displayed the predicted size shift of the hybridizing band. Germ line-transmitting chimeras yielded Siah2 heterozygotes, which were intercrossed to produce progeny of all three genotypes (Fig. 1B).

Northern blotting using a probe isolated from the 3′ untranslated region of Siah2 revealed that expression of Siah2 mRNA is abolished by the mutation (Fig. 1C). This probe also hybridized with a weakly expressed larger transcript in heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice. This band was also detected using a probe spanning exons I and II and using a NeoR probe, suggesting that this transcript results from read-through of the NeoR cassette (data not shown). Siah2 mRNA is expressed at low levels in most mouse tissues (8). We generated polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies that recognize recombinant and overexpressed Siah2 in Western blotting and immunoprecipitation (17), but these were of insufficient sensitivity to detect endogenous Siah2 protein in any tissue or cell line derived from wild-type mice (data not shown). To further confirm loss of Siah2 expression, we performed in situ hybridization to developing ovarian follicles, a site where Siah2 mRNA is normally strongly expressed (7). When an antisense riboprobe located 3′ of the insertion site was used for this analysis we found that expression of Siah2 mRNA was lost in mutant mice (Fig. 1F and G) while being evident in wild-type mice (Fig. 1D and E), confirming that targeting of the locus was successful. Siah1 protein expression is not altered in MEFs, lymphocytes, or tissues from Siah2 mutant mice (reference 12 and data not shown).

Phenotypic analysis of Siah2 mutant mice.

Siah2 homozygous mutant mice were born at the expected Mendelian frequency from intercrosses of Siah2 heterozygous mice (29 Siah2+/+:57 Siah2+/−:31 Siah2−/−) and, unlike Siah1a mutant mice, did not exhibit growth retardation or early lethality. Siah2 mutant mice appear outwardly normal and healthy. As Siah1a mutant male mice exhibit a block in spermatogenesis (9) and Siah2 is highly expressed in germ cells in the ovary and testis (7), we analyzed reproductive tissues in Siah2 mutant mice. Both male and female Siah2 mutant mice are fertile and exhibit no histological abnormalities in ovaries (Fig. 1D and F) or testes (Fig. 2A and B).

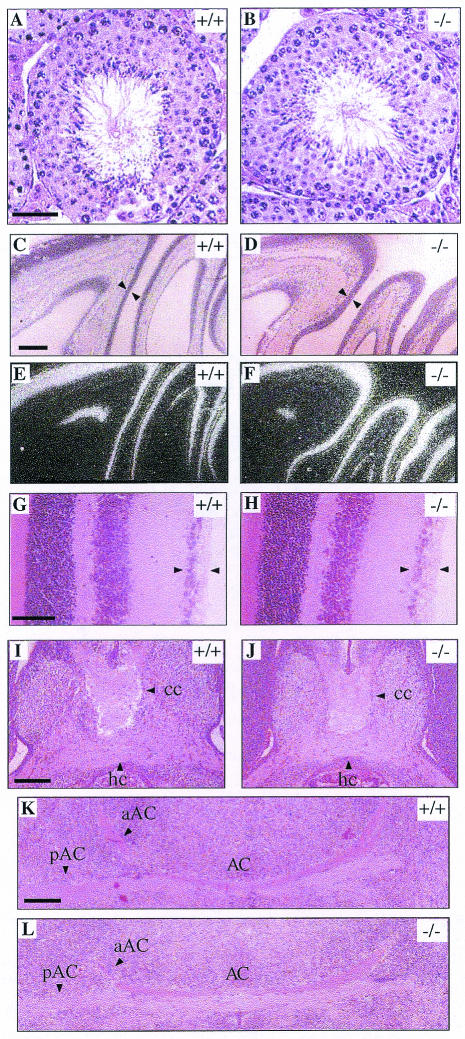

FIG. 2.

Histological analysis of Siah2 mutant mice. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of seminiferous tubules from adult wild-type (A) and Siah2−/− (B) mice. Note the presence of elongated spermatids and spermatozoa in wild-type and Siah2−/− mice. These cells are absent in Siah1a−/− mice (9). (C to F) Olfactory neuroepithelium in adult wild-type (C and E) and Siah2−/− (D and F) mice. Olfactory epithelium is marked by triangles in hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections (C and D) and by in situ hybridization, using an antisense riboprobe corresponding to nucleotides 242 to 958 of the olfactory marker protein cDNA, in dark-field illumination of sections (E and F). (G and H) Retina from adult wild-type (G) and Siah2−/− (H) mice. The ganglion cell layer is marked by arrowheads in these hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections. (I to K) Horizontal sections through brains of wild-type (I and K) and Siah2−/− (J and L) E18.5 embryos displaying axonal commissures of the corpus callosum (cc), hippocampal commissure (hc) (I and J), and posterior (pAC) and anterior (aAC) arms of the anterior commissure (AC) (K and L). The rostral part ofthe brain is shown at the top (C to F and I to L) or to the right (G and H). Scale bars: 50 μm (A to H) and 200 μm (I to L).

A number of studies link Siah2 to various aspects of neural function. Firstly, Siah2 is highly expressed in the olfactory neuroepithelium (8) and has been proposed to regulate apoptosis of olfactory neuronal cells by inducing the degradation of the antiapoptotic protein Bag-1 (42). While we have not excluded subtle differences in cellular turnover, the olfactory epithelium of mutant Siah2 adult (Fig. 2C and D) and neonatal (data not shown) mice appeared histologically normal and exhibited normal expression of a marker of olfactory neuronal epithelium cells, OMP (Fig. 2E and F) (15). Secondly, Siah2 has been implicated in eye development in Xenopus laevis (5) and Siah2 is highly expressed in the ganglion cell layer of the mouse retina during embryogenesis (8). Siah2 mutant mice reach for objects (such as a cage top) when lowered towards them, indicating that they are able to see, and display no histological abnormalities in any structures of the eye, including the retinal ganglion cell layer (Fig. 2G and D). Thirdly, to investigate the hypothesis that Siah2 regulates neuronal apoptosis (42) we investigated the survival of motoneurons following unilateral transection of the facial nerve of adult mice (33). After 14 days, counting the number of apoptotic cells in the facial nucleus of the lesioned side in comparison to the unlesioned side revealed no significant difference in specific motoneuron apoptosis between wild-type mice (20.9% ± 5.2%; n = 3 mice) and Siah2 mutant mice (15.2% ± 1.3%; n = 4 mice). Fourthly, findings that Siah2 can degrade the cell surface receptor DCC implicate Siah2 in the regulation of axonal path finding (21). However, axonal connections in the brain whose formation depends on DCC (10), including those of the corpus callosum (Fig. 2I and J), hippocampal commissure (Fig. 2I and J), and anterior commissure (Fig. 2K and L), are histologically normal in Siah2 mutant mice. All other organs of Siah2 mutant mice appeared to be histologically normal (data not shown).

Functional redundancy between Siah2 and Siah1a in vivo.

To investigate the effect of combined mutation of two of the three highly homologous murine Siah genes, we crossed heterozygous and homozygous Siah2 mutations into Siah1a mutant genetic backgrounds. While Siah1a−/− mice are born at normal Mendelian frequency, approximately 70% of pups die during the nursing period (9). We find that loss of a single copy of Siah2 enhances this phenotype with all Siah2+/− Siah1a−/− pups dying before weaning. Twelve of sixteen pups died within 1 day of birth, and 15 of these pups were dead by day 5. This phenotype of synthetic lethality was further enhanced by the loss of both copies of the Siah2 gene. Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− pups were born at a sub-Mendelian ratio from the intercross of Siah2−/− Siah1a+/− mice (35 Siah2−/− Siah1a+/+:57 Siah2−/− Siah1a+/−:19 Siah2−/− Siah1a−/−, or 1:1.6:0.5) and all died within hours of birth. Siah2 Siah1a double-mutant pups were the same weight at birth as Siah1a single-mutant pups, were born alive, exhibited normal breathing and reflexes, and did not exhibit any overt histological defects (data not shown). The cause of death of Siah2 Siah1a mutant mice remains to be identified. These findings demonstrate that as well as having unique functions, Siah2 and Siah1a perform partially overlapping functions in vivo.

Normal immune system development in the absence of Siah2 or both Siah2 and Siah1a.

As Siah2 has been implicated in regulating the activity of proteins that are important in immunity—including TRAF2, OBF-1, Vav1, and NF-κB—we analyzed hematopoietic development in Siah2 mutant mice. Loss of Siah2 did not affect the cellularity of thymus, spleen, lymph node, or bone marrow (data not shown), and flow cytometry demonstrated that the percentages of cells in each tissue that expressed T-cell markers (CD4 and CD8), B-cell markers (B220, IgM, and IgD), granulocyte and monocyte markers (Gr-1, Mac-1, and F4/80), or the erythroid marker TER-119 were unchanged in Siah2−/− mice (Table 1). To investigate the effect of combined mutation of Siah2 and Siah1a on hematopoiesis, fetal liver cells from Siah2−/− or Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− embryos (CD45.2 allotype) were adoptively transferred into irradiated host mice (CD45.1 allotype) and the hematopoietic system was analyzed after long-term reconstitution. Antibodies against CD45.2 and B-cell (B220), T-cell (CD4 and CD8), and myeloid (Mac-1) lineage markers demonstrated that fetal liver cells from Siah2−/− or Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− embryos functioned equivalently in reconstituting the hematopoietic system of lethally irradiated mice (Table 2). Thus, Siah2 and Siah1a are dispensable for steady-state hematopoiesis.

TABLE 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of hematopoietic lineages in wild-type and Siah2 mutant micea

| Organ and lineage marker(s) | % Positive white blood cells (mean ± SD) from mice

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Siah2−/− | |

| Thymus | ||

| CD4+ CD8+ | 86.4 ± 2.0 | 87.1 ± 0.9 |

| CD4+ CD8− | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.6 |

| CD8+ CD4− | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| Spleen | ||

| CD4+ CD8− | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 11.6 ± 0.2 |

| CD8+ CD4− | 11.1 ± 1.7 | 10.1 ± 0.4 |

| B220+ IgM+ | 52.1 ± 3.0 | 53.2 ± 1.0 |

| B220+ IgD+ | 50.8 ± 3.0 | 59.9 ± 2.0 |

| Mesenteric lymph node | ||

| CD4+ CD8− | 38.7 ± 2.5 | 36.3 ± 5.6 |

| CD8+ CD4− | 19.0 ± 2.3 | 22.8 ± 2.2 |

| B220+ IgM+ | 25.9 ± 3.2 | 24.9 ± 5.7 |

| B220+ IgD+ | 24.9 ± 2.4 | 21.5 ± 4.4 |

| Bone marrow | ||

| B220+ IgM− | 17.6 ± 1.0 | 21.2 ± 2.0 |

| B220+ IgM+ | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 9.7 ± 0.4 |

| B220+ IgD+ | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 0.7 |

| Mac-1+ | 38.3 ± 3.7 | 39.2 ± 2.4 |

| Gr-1+ | 45.8 ± 3.0 | 44.5 ± 1.5 |

| Mac-1+Gr-1high | 18.3 ± 2.3 | 16.4 ± 1.0 |

| F4/80+ | 47.3 ± 2.7 | 48.5 ± 2.8 |

| TER-119+ | 24.3 ± 4.0 | 23.9 ± 1.4 |

Three 8-week-old female mice of each genotype were analyzed. Data are percentages of white blood cells positive for the indicated markers.

TABLE 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of reconstitution of hematopoietic lineages in irradiated mice by Siah2−/− and Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− fetal liver cellsa

| Organ and lineage marker | % Positive cells (mean ± SD) from mice

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Siah2−/− | Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− | |

| Thymus | ||

| CD45.2+ | 97.4 ± 0.5 | 93.9 ± 6.2 |

| CD4+ | 77.9 ± 2.3 | 75.9 ± 4.2 |

| CD8+ | 79.9 ± 1.1 | 78.3 ± 3.7 |

| Spleen | ||

| CD45.2+ | 90.1 ± 4.8 | 87.0 ± 1.3 |

| CD4+ | 18.3 ± 1.1 | 13.0 ± 0.5 |

| CD8+ | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 1.1 |

| B220+ | 58.0 ± 1.2 | 59.2 ± 0.1 |

| Bone marrow | ||

| CD45.2+ | 70.9 ± 4.8 | 73.3 ± 4.3 |

| B220+ | 43.0 ± 5.5 | 35.9 ± 6.9 |

| Mac-1+ | 43.9 ± 6.7 | 46.8 ± 1.8 |

Data represent the results of an analysis of three recipient mice 19 weeks after adoptive transfer of fetal liver cells from Siah2−/− or Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− embryos and are percentages of total white blood cells that are derived from donor fetal livers (CD45.2+) and percentages of CD45.2+ cells that express the indicated T, B, and myeloid lineage markers.

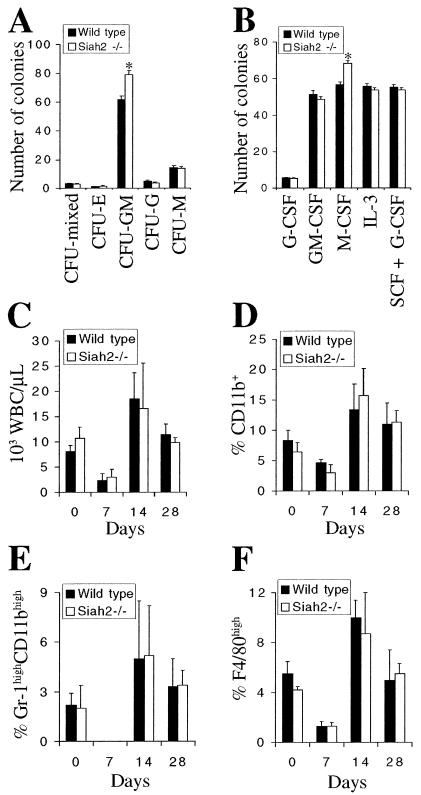

Interestingly, semisolid colony-forming cell assays revealed that bone marrow from Siah2 mutant mice contains an expanded myeloid progenitor compartment. Siah2−/− bone marrow yielded 28% more CFU-GM colonies than wild-type bone marrow in 12-day methylcellulose colony-forming cell assays (Fig. 3A). This assay uses a cocktail of IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and erythropoietin to support growth of all myeloid and erythroid lineage progenitors. The frequencies of the earliest progenitor cell in the myeloid-erythroid lineage (CFU-mixed lineage) and of committed erythroid (CFU-E), granulocyte (CFU-G), and macrophage (CFU-M) progenitor cells were unaffected by loss of Siah2 under this cytokine stimulation (Fig. 3A). To further define the cell type that is expanded in Siah2 mutant mice, we assessed colony formation in 7-day agar colony-forming cell assays using cytokines that induce growth of defined lineages. In these assays, Siah2−/− bone marrow generated 20% more colonies than wild-type bone marrow in response to M-CSF but not in response to G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-3, or G-CSF plus SCF (Fig. 3B). Granulocyte, macrophage, and granulocyte-macrophage colonies were present in the same percentages in M-CSF cultures derived from each genotype (data not shown), demonstrating that the observed increase in colony number in response to M-CSF does not result from expansion of a single specific myeloid cell type.

FIG. 3.

Expansion of myeloid progenitors in Siah2 mutant mice. (A) Twelve-day methylcellulose colony-forming cell assay of bone marrow from wild-type and Siah2−/− mice. Bone marrow was obtained from six mice of each genotype, and each sample was cultured in duplicate with IL-3 (1,000 U/ml), IL-6 (1,000 U/ml), SCF (approximately 100 ng/ml), and erythropoietin (2 U/ml). Colony type was assigned based on distinctive morphology, and mean colony numbers are shown (error bars, standard errors of the means). *, statistically significant difference between genotypes (P < 0.00003; Student's t test). (B) Seven-day agar colony-forming cell assay of bone marrow from wild-type and Siah2−/− mice. Bone marrow was obtained from six mice of each genotype, and each sample was cultured in duplicate. Data represent mean numbers of colonies (error bars, standard errors of the means) after 7 days of culture with either G-CSF (1,000 U/ml), GM-CSF (1,000 U/ml), M-CSF (20 ng/ml), IL-3 (1,000 U/ml), or SCF (approximately 100 ng/ml) and G-CSF (1,000 U/ml). *, statistically significant difference between genotypes (P < 0.001; Student's t test). (C to F) Hematopoietic recovery assay after intraperitoneal injection of wild-type and Siah2−/− mice with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg of body weight). Peripheral blood was analyzed at the time of injection (day 0) and 7, 14, and 28 days after injection for total white blood cell counts (C), percentage of white blood cells expressing the common myeloid marker CD11b (D), high levels of Gr-1 and CD11b (markers of mature granulocytes) (E), or high levels of F4/80 (marker of macrophages) (F). Data represent means + standard deviations (error bars) from analysis of five wild-type and four Siah2−/− mice.

The expansion of myeloid progenitor cells does not alter steady-state levels of myeloid lineages in vivo, as the frequency of expression of myeloid markers (Mac-1, F4/80, and Gr-1) is normal in bone marrow (Table 1) and spleen and peripheral blood (data not shown) of Siah2 mutant mice. To investigate whether myeloid defects may be apparent during non-steady-state hematopoiesis, we monitored hematopoietic recovery after elimination of progenitor cells and mature lineages by injection of 5-fluorouracil. The recovery of white blood cell counts (Fig. 3C) and of frequency of expression of myeloid cell (Fig. 3D), mature granulocyte (Fig. 3E), and macrophage (Fig. 3F) markers were equivalent in wild-type and Siah2−/− mice. Red blood cell and platelet counts, and B- and T-cell frequencies, also recovered normally (data not shown). Thus, even during hematopoietic system repopulation, mechanisms of homeostasis appear to act to maintain the normal production of mature myeloid cells from an expanded population of progenitor cells in Siah2 mutant mice.

Enhanced osteoclast production in vitro, but normal in vivo bone metabolism, in Siah2−/− mice.

Hematopoietic colonies elicited by M-CSF in semisolid medium contain osteoclast progenitors capable of both proliferation and differentiation in vitro (58). To assess whether the expansion of M-CSF-responsive colony-forming cells in Siah2 mutant mice might affect osteoclast production, we induced in vitro osteoclast formation from bone marrow in the presence of human CSF-1 (the human homologue of mouse M-CSF which can functionally substitute for M-CSF in mouse cells) and using purified GST-RANKL as the osteoclastogenic stimulus (37). Bone marrow from Siah2 mutant mice yielded almost twice as many osteoclasts as bone marrow from wild-type mice in these cultures (Fig. 4A). Cultures from wild-type and Siah2−/− mice that were grown in the absence of GST-RANKL yielded equivalent numbers of adherent cells (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that the enhanced formation of osteoclasts does not simply reflect an increase in proliferation of Siah2−/− cells in response to CSF-1. In light of this finding, and of the observations that Siah2 mRNA is highly expressed in cartilage undergoing endochronal ossification (8), we analyzed skeletal development in Siah2−/− mice. Alizarin red-S and Alcian blue staining of wild-type and Siah2 mutant embryonic-day-17.5 (E17.5) embryos revealed no differences between genotypes in cartilage and bone development (Fig. 4C). Similarly, histomorphometric analysis of tibiae from Siah2 mutant mice revealed no alterations in bone size, structure, or numbers or in activity of osteoclasts or osteoblasts in vivo (Fig. 4D and Table 3). Thus, the enhanced formation of osteoclasts observed in vitro is not reflected in vivo in Siah2−/− mice.

FIG. 4.

Osteoclast formation and analysis of bone structure in Siah2 mutant mice. (A) Bone marrow cells from wild-type or Siah2−/− mice were cultured in 48-well plates at a starting density of 105 cells/well in the presence of CSF-1 (20 ng/ml) and GST-RANKL fusion protein (100 ng/ml) for 7 days. Osteoclast formation was assessed by TRAP staining. TRAP+ multinuclear cells (three or more nuclei) were scored as osteoclasts. Data represent means + standard error of means (SEM) derived from four independent experiments. In each experiment, bone marrows from two or three mice were pooled and osteoclast formation was induced in five separate wells. Statistically significant differences between genotypes are depicted (*, P < 0.001; Student's t test). (B) Bone marrow cells pooled from three wild-type and three Siah2−/− mice were cultured in the presence of human CSF-1 (10,000 U/ml) on 35-mm-diameter bacterial petri dishes at a starting cell density (1.2 × 106 cells/dish) equivalent to that of cultures in panel A. Medium was replaced every 3 days, and the number of adherent cells was determined at day 7 by harvesting in 0.54 mM EDTA in PBS. Data represent mean numbers of cells per plate + SEM (error bars) and are derived from six separate cultures of each genotype. (C) Alizarin red-S (bone) and Alcian blue (cartilage) staining of wild-type and Siah2−/− E17.5 embryos. (D) Representative sections of tibiae from 10-week-old female wild-type and Siah2−/− mice, stained by a modification of the von Kossa technique (bone is stained black).

TABLE 3.

Histomorphometric analysis of bone structure and remodelling in Siah2 mutant micea

| Parameter | Mean ± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type mice | Siah2−/− mice | |

| Femoral length (mm) | 14.5 ± 0.3 | 14.3 ± 0.2 |

| Femoral width (mm) | 1.45 ± 0.10 | 1.31 ± 0.05 |

| Cortical thickness (μm) | 101 ± 3 | 97 ± 6 |

| Trabecular bone volume (%) | 6.9 ± 2.4 | 5.9 ± 1.1 |

| Trabecular no. (per mm) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| Trabecular thickness (μm) | 28.8 ± 4.0 | 28.0 ± 2.4 |

| Trabecular separation (μm) | 686 ± 184 | 571 ± 105 |

| Osteoblast surface (%) | 25.3 ± 2.0 | 31.5 ± 3.4 |

| Osteoid vol/bone vol (%) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 0.7 |

| Osteoid thickness (μm) | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| Mineral appositional rate (μm/day) | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

| Mineralizing surface (%) | 14.0 ± 3.2 | 19.9 ± 3.6 |

| Osteoclast surface (%) | 10.2 ± 0.9 | 13.1 ± 2.0 |

| Osteoclast no. (per mm of BPM) | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

Data are means ± standard errors of the means from an analysis of metaphyseal regions of tibiae from 8-week-old wild-type (n = 8) and Siah2−/− (n = 7) mice. No statistically significant difference among mice of different genotypes was found for any parameter (by ANOVA and Fisher's post hoc test). BPM, bone perimeter.

Normal TNF-α-mediated signaling and cellular response in Siah2 mutant primary cells.

Since our previous structural, biochemical, and genetic observations implicate Siah2 in the degradation of TRAF2 (17, 36), we focused further analysis of Siah2 deficient mice on signaling and cellular events that are mediated by TRAF2 and other TRAF proteins.

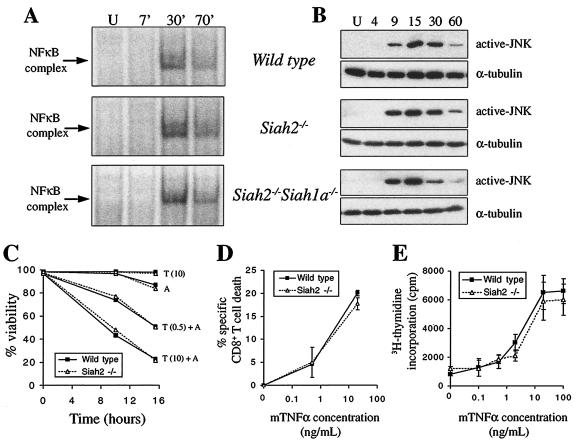

TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB is mediated by TRAF2 and TRAF5 (46, 59), and TNF-α-induced JNK activation is completely eliminated by loss of TRAF2 (59). As we have shown that Siah2 regulates TRAF2 abundance in response to treatment with TNF-α plus actinomycin D or cycloheximide, and that overexpression of Siah2 inhibits TNF-α-induced NF-κB and JNK activation (17), it was of interest to determine whether TRAF2-mediated signal transduction is altered in Siah2 mutant cells. We hypothesized that Siah2 may degrade TRAF2 in response to activation of TNF-α receptors and may thus serve to limit the duration or magnitude of TNF-α signaling responses. However, stimulation of wild-type and Siah2−/− primary MEFs with submaximal doses of TNF-α revealed identical magnitude and time course of NF-κB and JNK activation in each genotype (Fig. 5A and B). Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− MEFs similarly displayed normal activation of NF-κB and JNK in response to TNF-α (Fig. 5A and B). Thus, signal transduction by TRAF2 is not altered by loss of Siah2 and Siah1a in primary cells.

FIG. 5.

Normal TNF-α signaling and cellular responses in Siah2 mutant primary cells. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from wild-type, Siah2−/−, and Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− MEFs that were unstimulated (U) or treated with a submaximal dose of TNF-α (0.2 ng/ml) for 7, 30, or 70 min. NF-κB binding activity was analyzed by EMSA after incubation of nuclear extracts (5 μg of total protein) at room temperature for 20 min with 32P-radiolabeled κB3 double-stranded oligonucleotide. In each experiment, two or three independent MEF preparations of each genotype were pooled prior to stimulation. (B) Pools of MEFs (as in panel A) were treated with a submaximal dose of TNF-α (0.2 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods (minutes), and JNK activation was analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody that specifically detects doubly phosphorylated JNK. (C) Wild-type or Siah2−/− MEFs were treated with either TNF-α (10 ng/ml) [T(10)] or TNF-α (0.5 ng/ml) [T(0.5)] in the presence or absence of actinomycin D (1 μg/ml) (A). Cellular viability was assessed after 10 and 16 h by flow cytometry and exclusion of propidium iodide by viable cells. Data represent averages of duplicate determinations (range, less than 10% of the mean [not shown]) for each treatment, and similar results were seen in two independent experiments. (D) Lymph node T cells pooled from two 8-week-old wild-type or Siah2−/− mice were activated in vitro for 2 days with ConA (5 μg/ml), washed with α-methylmannoside (100 μg/ml) to remove ConA, and cultured for a further 2 days with IL-2 (100 U/ml). Cells were treated with TNF-α (0.5 or 20 ng/ml) for 48 h and analyzed by flow cytometry using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD4, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD8, and 7-AAD. Specific CD8+-T-cell death was determined by calculating the percentage of total viable cells (exclusion of 7-AAD) that stained positive for CD8 in untreated cultures minus the percentage in TNF-α-treated cultures. Data represent means ± standard deviations (error bars) of triplicate cultures for each treatment. (E) Thymocytes from 8-week-old wild-type or Siah2−/− mice were cultured in vitro for 64 h in the presence of a submitogenic dose of ConA (0.5 μg/ml) and increasing concentrations of TNF-α. Proliferation was analyzed by [3H]thymidine incorporation for the final 16 h of culture. Data represent means ± standard deviations (error bars) of triplicate activations from each of three mice of each genotype.

TNF-α induces signals that can lead either to apoptosis or to cellular activation, proliferation, and differentiation (29). Most cell types are resistant to the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α due to the NF-κB-mediated induction of prosurvival signaling pathways (3, 55). Treatment with actinomycin D or cycloheximide renders cells sensitive to apoptosis in response to TNF-α due to inhibition of NF-κB-induced expression of antiapoptotic genes. TRAF2 mutant MEFs are hypersensitive to apoptosis induced by TNF-α plus cycloheximide (59) and overexpression of Siah2 sensitized cells to the same treatment (17). However, wild-type and Siah2 mutant MEFs were equally sensitive to apoptosis induced by TNF-α plus actinomycin D (Fig. 5C) or cycloheximide (data not shown). Mitogenically activated CD8+ T cells undergo apoptosis in response to TNF-α in the absence of RNA or protein synthesis inhibitors, a physiological process that contributes to downregulation of immune responses in vivo by removing activated T cells (38, 45, 62). Activated CD8+ T cells from wild-type and Siah2 knockout mice were equally sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α (Fig. 5D). Finally, thymocytes treated in vitro with submitogenic doses of ConA are induced to proliferate when the TNFR2 receptor is stimulated with TNF-α (51, 52). Thymocytes from Siah2 mutant mice proliferated equivalently to wild-type thymocytes when stimulated with TNF-α and ConA (Fig. 5E). These findings demonstrate that loss of Siah2 does not modulate the sensitivity of MEFs or T cells to TNF-α-mediated apoptotic or proliferative responses.

Normal lymphocyte proliferation, antibody production and macrophage activation in Siah2 mutant mice.

It is possible that Siah2 may regulate degradation of TRAF proteins other than TRAF2. Since TRAF family proteins transduce signals from a range of receptors in diverse cell types, loss of Siah2 expression may have phenotypic consequences that are cell type and/or stimulus specific. To address this possibility we examined a range of known TRAF-mediated cellular responses in Siah2 mutant mice and cells.

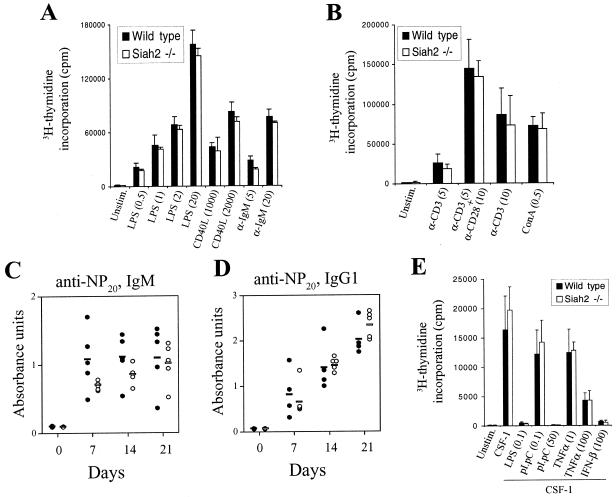

To assess TRAF-mediated lymphocyte proliferation in Siah2−/− mice, splenocytes were activated in vitro with LPS, which requires TRAF6 for induction of B-cell proliferation (30), or with CD40L, which requires TRAF2, TRAF5, and TRAF6 for optimal B-cell proliferative responses (30, 34, 35). B-cell proliferation in response to submaximal and maximal doses of both mitogens was unaltered by loss of Siah2 (Fig. 6A). Siah2 is also proposed to function as a negative regulator of Vav1 signaling (14). Vav1 is necessary for B- and T-lymphocyte proliferative responses to antigen receptor activation, but not for proliferation induced by other mitogens (11, 49, 61). To analyze Vav1-mediated proliferative responses in Siah2 mutant mice, splenic B cells were activated with agonistic antibodies against IgM (Fig. 6A) and T cells were activated with agonistic antibodies against the T-cell receptor subunit CD3ɛ or with ConA, which induces cross-linking of the T-cell receptor (Fig. 6B). Loss of Siah2 did not affect B- or T-cell proliferation in response to antigen receptor activation. Thus, loss of Siah2, which is proposed to function as a negative regulator of TRAF and Vav1 signaling, does not enhance TRAF- and Vav1-mediated lymphocyte proliferative responses.

FIG. 6.

Normal TRAF-, Vav1-, and OBF-1-mediated responses in Siah2 mutant mice and primary cells. (A) B-cell proliferation. Splenic white blood cells from 8-week-old wild-type or Siah2−/− mice were activated in vitro for 72 h with LPS (0.5, 1, 2, and 20 μg/ml) or anti-IgM (5 and 20 μg/ml) or by culture on irradiated 3T3 fibroblasts expressing CD40L (1,000 and 2,000 irradiated cells per well). Proliferation was analyzed by [3H]thymidine incorporation for the final 16 h of culture. Data represent the means + standard deviations (SD) (error bars) of triplicate activations from each of three mice of each genotype. (B) T-cell proliferation was analyzed as in panel A after stimulation of splenic white blood cells in 96-well plates with ConA (0.5 μg/ml) or by culture in wells coated with anti-CD3 (5 and 10 μg/ml) or anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml) antibodies. (C and D) Wild-type (•) or Siah2−/− (○) mice received intraperitoneal injections with 10 μg of the T-independent antigen NP-LPS (C) or with 100 μg of the T-dependent antigen NP-KLH precipitated on alum (D). Serum samples were obtained at time points after immunization and analyzed using an anti-NP and IgM-specific ELISA (C) or an anti-NP and IgG1-specific ELISA. Each circle in panel C represents the absorbance reading obtained from a 1:1,585 dilution of serum from an immunized mouse (the absorbance reading was linear with respect to dilution over the range 1:500 to 1:5,000), and each circle in panel D represents the absorbance reading obtained from a 1:10,000 dilution of serum from an immunized mouse (the absorbance reading was linear with respect to dilution over the range 1:3,170 to 1:31,700). Mean values are shown by horizontal lines. (E) Confluent BMM pooled from two wild-type or Siah2−/− mice were starved of M-CSF for 24 h prior to stimulation for a further 24 h with recombinant CSF-1 (10,000 U/ml) alone or in combination with LPS (0.1 μg/ml), poly(I) · poly(C) (pI.pC, 0.1 or 50 μg/ml), TNF-α (1 or 100 ng/ml), or IFN-β (100 U/ml). DNA synthesis was measured by incorporation of [3H]thymidine for the final 8 h of culture. Data represent means + SD (error bars) of triplicate stimulations.

We analyzed in vivo antibody production in Siah2 mutant mice for two reasons. Firstly, TRAF2 and TRAF3 mutant mice display defects in T-cell-dependent, but not T-cell-independent, antibody production (35, 57). Secondly, like Siah1a, Siah2 also interacts with OBF-1 (4). While the significance of this interaction has yet to be investigated, it is possible that Siah2 may regulate OBF-1 function during germinal center formation and may thus regulate adaptive antibody-mediated immunity. Wild-type or Siah2−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH to induce T-cell-dependent antibody responses (40), or with NP-LPS to induce T-cell-independent antibody responses (2). Serum samples were obtained at time intervals after immunization and analyzed using ELISA to detect NP-specific antibodies. The T-cell-independent response was monitored using serum IgM specific for NP, and this was found at equivalent levels in wild-type and Siah2−/− mice over the course of the response (Fig. 6C). Similarly, levels of NP-binding IgG1 were used to monitor the T-cell-dependent response, and again, no differences were observed between mice (Fig. 6D). Thus, TRAF2, TRAF3, and OBF-1 function normally during responses to antigens in Siah2 mutant mice.

Finally, TRAF-mediated signaling is important in macrophage activation induced by bacterially produced LPS, virally produced double-stranded RNA [mimicked by synthetic poly(I) · poly(C)], and endogenous inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α (1, 18). Macrophages respond to these activating stimuli by undergoing G1-phase cell cycle arrest and secreting cytokines and toxic nitric oxide (1, 54). The antiproliferative effects of activation of TRAF-dependent receptors are mediated by the production of IFN-α/β(18, 22). To analyze the role of Siah2 in antiproliferative TRAF-mediated signaling, BMM derived from wild-type and Siah2−/− mice were stimulated for 24 h with recombinant human CSF-1 in the presence or absence of LPS, poly(I) · poly(C), TNF-α, or IFN-β and proliferation was assessed by incubation with [3H]thymidine for the final 8 h of culture. Antiproliferative responses induced by all stimuli were equivalent in wild-type and Siah2−/− macrophages (Fig. 6E).

In conclusion, a number of well-characterized in vivo and ex vivo TRAF-mediated responses are unaffected by mutation of Siah2.

DISCUSSION

Highly conserved Siah homologues have been identified in all multicellular organisms examined. Biochemical studies of Siah proteins in plants, flies, mice, and humans have demonstrated that these proteins function as E3 ubiquitin ligase enzymes. However, the physiological processes that are regulated by vertebrate Siah proteins remain largely unclear. Siah2 is the most divergent member of the mouse Siah protein family, with Siah1a and Siah1b differing from one another at only a few amino acid positions. It is therefore surprising that mutation of Siah2 induces only very minor phenotypic consequences while Siah1a mutation results in severe growth retardation, early lethality, and spermatogenic defects.

The expression patterns of Siah1 and Siah2 genes yield few clues as to their specific functions. Mouse Siah1a, Siah1b, and Siah2 appear to be ubiquitously expressed (8; unpublished observations). High Siah1 expression in testes (7) correlates with the spermatogenic phenotype in Siah1a mutant mice (9). In contrast, sites of high Siah2 expression, including ovaries, testes, cartilage, and retinal and olfactory neuroepithelia (7, 8), are histologically normal in Siah2 mutant mice.

Siah2 mutant mice exhibit an expansion of the bone marrow myeloid progenitor compartment. Methylcellulose assays revealed an increased number of CFU-GM colonies, while agar assays conducted under restricted cytokine stimulation revealed an increased number of colonies in response to M-CSF. These data suggest that at least in in vitro assays, Siah2 is important in the regulation of the myeloid progenitor compartment, in particular those progenitors that are responsive to M-CSF. Our observation of increased osteoclast yield in in vitro cultures of bone marrow from Siah2 mutant mice is consistent with previous findings that osteoclasts derive from an M-CSF-responsive myeloid lineage progenitor (58). The M-CSF phenotype appears to be restricted to an early myeloid progenitor cell type, since we observed no differences between wild-type and Siah2 mutant mice in (i) the yield of nonadherent BMM precursor cells after culture of bone marrow for 3 days in M-CSF (data not shown), (ii) the yield of adherent cells (mostly BMM) after culture of bone marrow for 7 days in CSF-1 (Fig. 4B), and (iii) the proliferation of M-CSF-starved BMM after restimulation with CSF-1 (Fig. 6E). The mechanism by which Siah2 regulates myelopoiesis is not clear. Real-time PCR analysis of Siah1 and Siah2 expression in fluorescence-activated cell sorter-purified hematopoietic cell populations did not reveal any obvious expression pattern that would indicate a myeloid lineage-specific function for Siah2. Siah genes appear to be expressed in all progenitor and mature hematopoietic cell populations (data not shown). In summary, while there is an expansion of myeloid progenitor cells in Siah2 mutant mice, homeostatic mechanisms appear to tightly control the production of mature cells to ensure that the total cellularity of hematopoietic tissues and the frequency of granulocytes, macrophages, and osteoclasts remain unaffected.

Overexpression studies have implicated Siah2 in the degradation or inhibition of the activity of a number of proteins that participate in diverse signaling pathways. These include DCC, Vav1, OBF-1, and TRAF2 (4, 14, 17, 20, 21, 53). In this study we focused our analysis of the effects of loss of Siah2 on cellular or physiological processes that are mediated by putative Siah2 targets. We showed that DCC-mediated formation of axonal commissures, Vav1-mediated proliferation of B and T lymphocytes, in vivo OBF-1-mediated antibody production, and a variety of signaling and cellular responses mediated by TRAF2 and other TRAF family proteins are unaltered in Siah2 mutant mice. Therefore, loss of Siah2 alone does not grossly alter a range of physiological processes that require putative Siah2 substrate proteins.

One explanation for the absence of phenotypes may be that the abundance of Siah2 substrate proteins are regulated by factors other than Siah2. Supporting this idea, protein abundance of TRAF2 in MEFs is unaffected by loss of Siah2, yet the half-life of exogenously expressed TRAF2 is longer in Siah2 mutant MEFs (17). These data are consistent with the notion that alterations in rates of transcription or translation may act to maintain normal steady-state abundance of Siah2 target proteins in Siah2 mutant mice.

Finally, functional redundancy between Siah2 and Siah1 genes may obscure phenotypic consequences of loss of Siah2. We find that loss of a single copy of Siah2 enhances the phenotype of early lethality caused by Siah1a homozygous mutation. This phenotype is further enhanced by removal of both copies of Siah2, with Siah2−/− Siah1a−/− mice being born at sub-Mendelian frequency and subsequently dying within hours of birth. Thus, Siah1a and Siah2 appear to perform partially overlapping functions in vivo. Functional compensation by Siah1a and Siah1b may therefore maintain normal regulation of Siah2 substrate proteins in Siah2−/− mice. Our ongoing experiments aiming to generate Siah1b mutant mice and Siah double- and triple-mutant animals should further our understanding of the full repertoire of physiological functions of the Siah gene family.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael Sendtner for his generous collaboration with motoneuron apoptosis experiments and to David Haylock for performing differential counts of myeloid colonies. We also thank Hasem Habelhah, Ze'ev Ronai, David Sassoon, and Paul Hertzog for numerous helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants to D.D.L.B. and M.T.G. from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). L.E.P. is supported by a Special Fellowship of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, N.A.S. is supported by an R. D. Wright Fellowship of the NHMRC, and A.J.H. was supported by a guest scientist grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexopoulou, L., A. C. Holt, R. Medzhitov, and R. A. Flavell. 2001. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413:732-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr, T. A., and A. W. Heath. 1999. Enhanced in vivo immune responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide by exogenous CD40 stimulation. Infect. Immun. 67:3637-3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beg, A. A., and D. Baltimore. 1996. An essential role for NF-κB in preventing TNF-α-induced cell death. Science 274:782-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehm, J., Y. He, A. Greiner, L. Staudt, and T. Wirth. 2001. Regulation of BOB.1/OBF.1 stability by SIAH. EMBO J. 20:4153-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogdan, S., S. Senkel, F. Esser, G. U. Ryffel, and E. Pogge v. Strandmann. 2001. Misexpression of Xsiah-2 induces a small eye phenotype in Xenopus. Mech. Dev. 103:61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carthew, R. W., and G. M. Rubin. 1990. seven in absentia, a gene required for specification of R7 cell fate in the Drosophila eye. Cell 63:561-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Della, N. G., D. D. Bowtell, and F. Beck. 1995. Expression of Siah-2, a vertebrate homologue of Drosophila sina, in germ cells of the mouse ovary and testis. Cell Tissue Res. 279:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Della, N. G., P. V. Senior, and D. D. Bowtell. 1993. Isolation and characterisation of murine homologues of the Drosophila seven in absentia gene (sina). Development 117:1333-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickins, R. A., I. J. Frew, C. M. House, M. K. O'Bryan, A. J. Holloway, I. Haviv, N. Traficante, D. M. de Kretser, and D. D. Bowtell. 2002. The ubiquitin ligase component Siah1a is required for completion of meiosis I in male mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2294-2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazeli, A., S. L. Dickinson, M. L. Hermiston, R. V. Tighe, R. G. Steen, C. G. Small, E. T. Stoeckli, K. Keino-Masu, M. Masu, H. Rayburn, J. Simons, R. T. Bronson, J. I. Gordon, M. Tessier-Lavigne, and R. A. Weinberg. 1997. Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dcc) gene. Nature 386:796-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, K. D., Y. Y. Kong, H. Nishina, K. Tedford, L. E. Marengere, I. Kozieradzki, T. Sasaki, M. Starr, G. Chan, S. Gardener, M. P. Nghiem, D. Bouchard, M. Barbacid, A. Bernstein, and J. M. Penninger. 1998. Vav is a regulator of cytoskeletal reorganization mediated by the T-cell receptor. Curr. Biol. 8:554-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frew, I. J., R. A. Dickins, A. R. Cuddihy, M. Del Rosario, C. Reinhard, M. J. O'Connell, and D. D. Bowtell. 2002. Normal p53 function in primary cells deficient for Siah genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8155-8164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germani, A., H. Bruzzoni-Giovanelli, A. Fellous, S. Gisselbrecht, N. Varin-Blank, and F. Calvo. 2000. SIAH-1 interacts with α-tubulin and degrades the kinesin Kid by the proteasome pathway during mitosis. Oncogene 19:5997-6006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germani, A., F. Romero, M. Houlard, J. Camonis, S. Gisselbrecht, S. Fischer, and N. Varin-Blank. 1999. hSiah2 is a new Vav binding protein which inhibits Vav-mediated signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3798-3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graziadei, G. A., R. S. Stanley, and P. P. Graziadei. 1980. The olfactory marker protein in the olfactory system of the mouse during development. Neuroscience 5:1239-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grumont, R. J., I. B. Richardson, C. Gaff, and S. Gerondakis. 1993. rel/NF-κB nuclear complexes that bind κB sites in the murine c-rel promoter are required for constitutive c-rel transcription in B-cells. Cell Growth Differ. 4:731-743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habelhah, H., I. J. Frew, A. Laine, P. W. Janes, F. Relaix, D. Sassoon, D. D. Bowtell, and Z. Ronai. 2002. Stress-induced decrease in TRAF2 stability is mediated by Siah2. EMBO J. 21:5756-5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton, J. A., G. A. Whitty, I. Kola, and P. J. Hertzog. 1996. Endogenous IFN-αβ suppresses colony-stimulating factor (CSF)-1-stimulated macrophage DNA synthesis and mediates inhibitory effects of lipopolysaccharide and TNF-α. J. Immunol. 156:2553-2557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu, G., Y. L. Chung, T. Glover, V. Valentine, A. T. Look, and E. R. Fearon. 1997. Characterization of human homologs of the Drosophila seven in absentia (sina) gene. Genomics 46:103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu, G., and E. R. Fearon. 1999. Siah-1 N-terminal RING domain is required for proteolysis function, and C-terminal sequences regulate oligomerization and binding to target proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:724-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu, G., S. Zhang, M. Vidal, J. L. Baer, T. Xu, and E. R. Fearon. 1997. Mammalian homologs of seven in absentia regulate DCC via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 11:2701-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang, S. Y., P. J. Hertzog, K. A. Holland, S. H. Sumarsono, M. J. Tymms, J. A. Hamilton, G. Whitty, I. Bertoncello, and I. Kola. 1995. A null mutation in the gene encoding a type I interferon receptor component eliminates antiproliferative and antiviral responses to interferons α and β and alters macrophage responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11284-11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue, J., T. Ishida, N. Tsukamoto, N. Kobayashi, A. Naito, S. Azuma, and T. Yamamoto. 2000. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) family: adapter proteins that mediate cytokine signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 254:14-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnsen, S. A., M. Subramaniam, D. G. Monroe, R. Janknecht, and T. C. Spelsberg. 2002. Modulation of TGFβ/Smad transcriptional responses through targeted degradation of the TGFβ inducible early gene-1 by the human seven in absentia homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30754-30759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, E., T. H. Bestor, and R. Jaenisch. 1992. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69:915-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, S., Y. Li, R. W. Carthew, and Z. C. Lai. 1997. Photoreceptor cell differentiation requires regulated proteolysis of the transcriptional repressor Tramtrack. Cell. 90:469-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, S., C. Xu, and R. W. Carthew. 2002. Phyllopod acts as an adaptor protein to link the sina ubiquitin ligase to the substrate protein tramtrack. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:6854-6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, J., J. Stevens, C. A. Rote, H. J. Yost, Y. Hu, K. L. Neufeld, R. L. White, and N. Matsunami. 2001. Siah-1 mediates a novel β-catenin degradation pathway linking p53 to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Mol. Cell 7:927-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locksley, R. M., N. Killeen, and M. J. Lenardo. 2001. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell 104:487-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lomaga, M. A., W. C. Yeh, I. Sarosi, G. S. Duncan, C. Furlonger, A. Ho, S. Morony, C. Capparelli, G. Van, S. Kaufman, A. van der Heiden, A. Itie, A. Wakeham, W. Khoo, T. Sasaki, Z. Cao, J. M. Penninger, C. J. Paige, D. L. Lacey, C. R. Dunstan, W. J. Boyle, D. V. Goeddel, and T. W. Mak. 1999. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes Dev. 13:1015-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuzawa, S., and J. C. Reed. 2001. Siah-1, SIP, and Ebi collaborate in a novel pathway for β-catenin degradation linked to p53 responses. Mol. Cell 7:915-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLeod, M. J. 1980. Differential staining of cartilage and bone in whole mouse fetuses by alcian blue and alizarin red S. Teratology 22:299-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaelidis, T. M., M. Sendtner, J. D. Cooper, M. S. Airaksinen, B. Holtmann, M. Meyer, and H. Thoenen. 1996. Inactivation of bcl-2 results in progressive degeneration of motoneurons, sympathetic and sensory neurons during early postnatal development. Neuron 17:75-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakano, H., S. Sakon, H. Koseki, T. Takemori, K. Tada, M. Matsumoto, E. Munechika, T. Sakai, T. Shirasawa, H. Akiba, T. Kobata, S. M. Santee, C. F. Ware, P. D. Rennert, M. Taniguchi, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 1999. Targeted disruption of Traf5 gene causes defects in CD40- and CD27-mediated lymphocyte activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9803-9808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen, L. T., G. S. Duncan, C. Mirtsos, M. Ng, D. E. Speiser, A. Shahinian, M. W. Marino, T. W. Mak, P. S. Ohashi, and W. C. Yeh. 1999. TRAF2 deficiency results in hyperactivity of certain TNFR1 signals and impairment of CD40-mediated responses. Immunity 11:379-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polekhina, G., C. M. House, N. Traficante, J. P. Mackay, F. Relaix, D. A. Sassoon, M. W. Parker, and D. D. Bowtell. 2002. Siah ubiquitin ligase is structurally related to TRAF and modulates TNF-alpha signaling. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:68-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn, J. M., G. A. Whitty, R. J. Byrne, M. T. Gillespie, and J. A. Hamilton. 2002. The generation of highly enriched osteoclast-lineage cell populations. Bone 30:164-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarin, A., M. Conan-Cibotti, and P. A. Henkart. 1995. Cytotoxic effect of TNF and lymphotoxin on T lymphoblasts. J. Immunol. 155:3716-3718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sims, N. A., P. Clement-Lacroix, F. Da Ponte, Y. Bouali, N. Binart, R. Moriggl, V. Goffin, K. Coschigano, M. Gaillard-Kelly, J. Kopchick, R. Baron, and P. A. Kelly. 2000. Bone homeostasis in growth hormone receptor-null mice is restored by IGF-I but independent of Stat5. J. Clin. Investig. 106:1095-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith, K. G., A. Light, G. J. Nossal, and D. M. Tarlinton. 1997. The extent of affinity maturation differs between the memory and antibody-forming cell compartments in the primary immune response. EMBO J. 16:2996-3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith, K. G., U. Weiss, K. Rajewsky, G. J. Nossal, and D. M. Tarlinton. 1994. Bcl-2 increases memory B cell recruitment but does not perturb selection in germinal centers. Immunity 1:803-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sourisseau, T., C. Desbois, L. Debure, D. D. Bowtell, A. C. Cato, J. Schneikert, E. Moyse, and D. Michel. 2001. Alteration of the stability of Bag-1 protein in the control of olfactory neuronal apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 114:1409-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanley, E. R., and L. J. Guilbert. 1981. Methods for the purification, assay, characterization and target cell binding of a colony stimulating factor (CSF-1). J. Immunol. Methods 42:253-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Susini, L., B. J. Passer, N. Amzallag-Elbaz, T. Juven-Gershon, S. Prieur, N. Privat, M. Tuynder, M. C. Gendron, A. Israel, R. Amson, M. Oren, and A. Telerman. 2001. Siah-1 binds and regulates the function of Numb. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15067-15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sytwu, H. K., R. S. Liblau, and H. O. McDevitt. 1996. The roles of Fas/APO-1 (CD95) and TNF in antigen-induced programmed cell death in T cell receptor transgenic mice. Immunity 5:17-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tada, K., T. Okazaki, S. Sakon, T. Kobarai, K. Kurosawa, S. Yamaoka, H. Hashimoto, T. W. Mak, H. Yagita, K. Okumura, W. C. Yeh, and H. Nakano. 2001. Critical roles of TRAF2 and TRAF5 in tumor necrosis factor-induced NF-κB activation and protection from cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 276:36530-36534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang, A. H., T. P. Neufeld, E. Kwan, and G. M. Rubin. 1997. PHYL acts to down-regulate TTK88, a transcriptional repressor of neuronal cell fates, by a SINA-dependent mechanism. Cell 90:459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanikawa, J., E. Ichikawa-Iwata, C. Kanei-Ishii, A. Nakai, S. Matsuzawa, J. C. Reed, and S. Ishii. 2000. p53 suppresses the c-Myb-induced activation of heat shock transcription factor 3. J. Biol. Chem. 275:15578-15585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarakhovsky, A., M. Turner, S. Schaal, P. J. Mee, L. P. Duddy, K. Rajewsky, and V. L. Tybulewicz. 1995. Defective antigen receptor-mediated proliferation of B and T cells in the absence of Vav. Nature 374:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tarlinton, D. M., M. McLean, and G. J. Nossal. 1995. B1 and B2 cells differ in their potential to switch immunoglobulin isotype. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:3388-3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tartaglia, L. A., D. V. Goeddel, C. Reynolds, I. S. Figari, R. F. Weber, B. M. Fendly, and M. A. Palladino, Jr. 1993. Stimulation of human T-cell proliferation by specific activation of the 75-kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. J. Immunol. 151:4637-4641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tartaglia, L. A., R. F. Weber, I. S. Figari, C. Reynolds, M. A. Palladino, Jr., and D. V. Goeddel. 1991. The two different receptors for tumor necrosis factor mediate distinct cellular responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:9292-9296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiedt, R., B. A. Bartholdy, G. Matthias, J. W. Newell, and P. Matthias. 2001. The RING finger protein Siah-1 regulates the level of the transcriptional coactivator OBF-1. EMBO J. 20:4143-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vadiveloo, P. K., E. Keramidaris, W. A. Morrison, and A. G. Stewart. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide-induced cell cycle arrest in macrophages occurs independently of nitric oxide synthase II induction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1539:140-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Antwerp, D. J., S. J. Martin, T. Kafri, D. R. Green, and I. M. Verma. 1996. Suppression of TNF-α-induced apoptosis by NF-κB. Science 274:787-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wheeler, T. C., L. S. Chin, Y. Li, F. L. Roudabush, and L. Li. 2002. Regulation of synaptophysin degradation by mammalian homologues of seven in absentia. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10273-10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu, Y., G. Cheng, and D. Baltimore. 1996. Targeted disruption of TRAF3 leads to postnatal lethality and defective T-dependent immune responses. Immunity 5:407-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamazaki, H., T. Kunisada, T. Yamane, and S. I. Hayashi. 2001. Presence of osteoclast precursors in colonies cloned in the presence of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors. Exp. Hematol. 29:68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeh, W. C., A. Shahinian, D. Speiser, J. Kraunus, F. Billia, A. Wakeham, J. L. de la Pompa, D. Ferrick, B. Hum, N. Iscove, P. Ohashi, M. Rothe, D. V. Goeddel, and T. W. Mak. 1997. Early lethality, functional NF-κB activation, and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death in TRAF2-deficient mice. Immunity 7:715-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, J., M. G. Guenther, R. W. Carthew, and M. A. Lazar. 1998. Proteasomal regulation of nuclear receptor corepressor-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 12:1775-1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, R., F. W. Alt, L. Davidson, S. H. Orkin, and W. Swat. 1995. Defective signalling through the T- and B-cell antigen receptors in lymphoid cells lacking the vav proto-oncogene. Nature 374:470-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng, L., G. Fisher, R. E. Miller, J. Peschon, D. H. Lynch, and M. J. Lenardo. 1995. Induction of apoptosis in mature T cells by tumour necrosis factor. Nature 377:348-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]