Abstract

Cellular senescence has emerged as a biological response to two major pathophysiological states of our being: cancer and aging. In the course of the transformation of a normal cell to a cancerous cell, senescence is frequently induced to suppress tumor development. In aged individuals, senescence is found in cells that have exhausted their replication potential. The similarity in these responses suggests that understanding how senescence is mediated can provide insight into both cancer and aging. One environmental factor that is implicated in both of these states is tissue hypoxia, which increases with aging and can inhibit senescence. Hypoxia is particularly important in normal physiology to maintain the stem cell niche; but at the same time, hypoxic inhibition of an essential tumor suppressor response can theoretically contribute to cancer initiation.

Introduction

Cellular senescence is a programmed response designed to remove damaged cells from the proliferative population as they age. Senescence can be induced by many stimuli, including telomere uncapping and shortening, DNA damage, oncogene activity, and oxidative stress, and is thought to provide a means to permanently arrest cells. As such, senescence serves a critical role as a tumor suppressor response that is mediated by classic tumor suppressor pathways, and is necessarily inactivated early in the transformation process (1).

Signals leading to senescence depend primarily on the p53 and pRb pathways both for induction and maintenance of cell cycle arrest (1). Seemingly different types of stresses lead to a common senescent phenotype through convergence upon these pathways. Telomere erosion, for example, is perceived by cells as DNA damage, and thus activates a typical DNA damage response involving p53 (2). Oncogene activity can affect both p53 and pRb through several mechanisms, including inducing a DNA damage response due to hyperreplication (3), or by inducing the expression of CDKN2A or CDKN2B (4, 5), that impinge upon pRb activity or p53 stability, respectively.

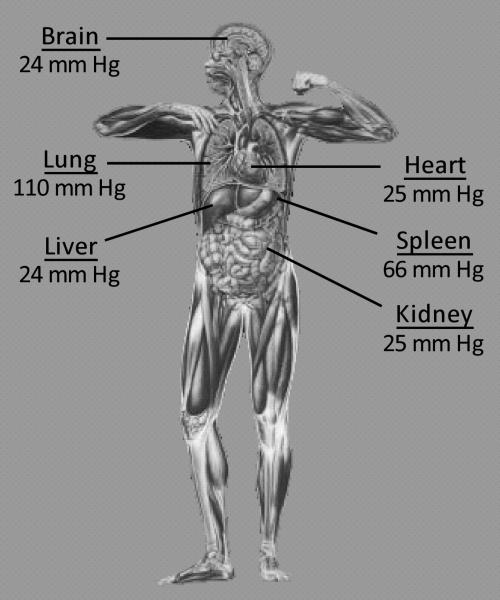

An underappreciated factor in the regulation of senescence is oxygen. Atmospheric pO2, which is common in standard tissue culture incubators, is roughly 160 mm Hg. In contrast, the partial pressure of oxygen in the body is significantly lower, even as it varies widely in different organs (figure 1). The pO2 in the in the alveoli of the lungs is 110 mm Hg, while the median pO2 in the brain, liver, and heart is near 24 mm Hg (6). Thus, much of our understanding of senescence comes from studies that have been performed in what is effectively hyperoxia, which itself can be a potent inducer of senescence (7). Intriguingly, various studies have shown that senescence from many different stimuli can be averted under lower levels of oxygen (8-10). This is true for replicative senescence as well as stress- and oncogene-induced senescence. Therefore in order to understand how and when senescence is induced in vivo, it is critical to understand the role of oxygen in regulating senescence.

Figure 1.

Levels of normal oxygen content in various organs throughout the body.

The goal of this review is to highlight recent and historical observations that contribute to the understanding of how hypoxia can modulate senescence. Insights into mediators of senescence in a number of different systems have recently come to light. Interestingly, independent connections to physiological hypoxia pull many of these novel mechanisms together onto a common playing field and will be discussed here.

Oxygen and oxidative stress

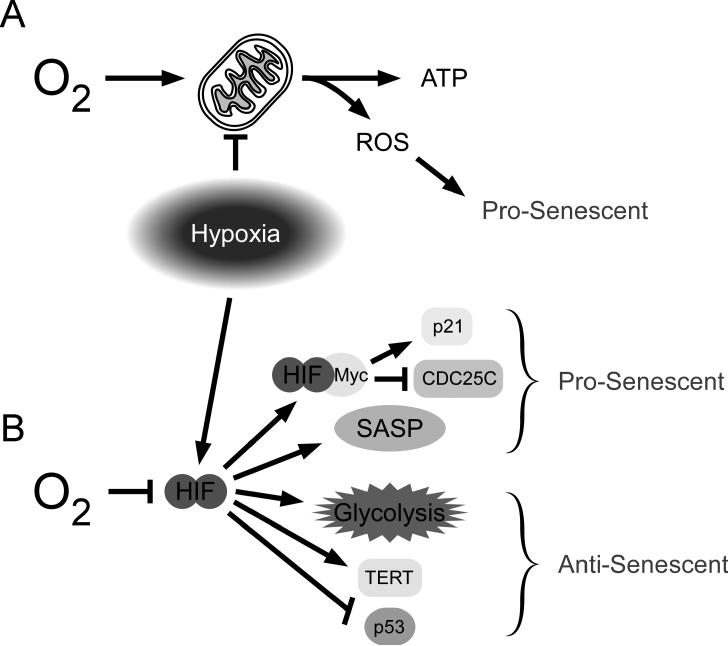

Supraphysiological levels of oxygen result in oxidative stress through the increased production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) (11). The classic model of senescence from hyperoxia is that ROS play a causative role in inducing senescence (7, 12). Conversely under lower oxygen, decreases in ROS rescue senescence (Figure 2a) (9, 10). There are several pieces of evidence that support this oxidative stress model. The first are the direct experiments of adding potent oxidizing agents (such as H2O2) or reducing agents (such as N-acetyl cysteine) to cells and observing induction or inhibition of senescence, respectively (8, 13, 14). Second, other inducers of senescence, such as oncogene activity, have been shown to increase intracellular ROS in a manner that is required to bring about senescence (8). Finally, senescence that is alleviated by culturing cells under low oxygen can be reinstated by inducing oxidative stress (e.g. with H2O2 or ionizing radiation) (15, 16). Thus, one mechanism that explains the reduction of senescence under low oxygen may simply be a reduction in oxidative stress.

Figure 2.

Hypoxia modulates senescence in a variety of ways. A. Excess oxygen feeds the mitochondria and produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can promote senescence. Reduced oxygen can reduce damaging ROS. B. Hypoxia leads to the stabilization of HIF, which impacts many pathways that can affect senescence. Binding to Myc can induce p21 expression and inhibit CDC25C, thereby promoting cell cycle arrest. HIF transcriptionally controls a number of genes in the senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) that can promote senescence in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. In contrast, HIF also promotes glycolysis and reduces oxidative phosphorylation through transcriptional regulation of glycolytic enzymes. HIF can induce expression of the telomerase active subunit (TERT) and negatively regulate p53 at several levels. These latter effects are all inhibitory to senescence.

The modulation of ROS by oxygen levels and the effects of ROS on senescence, however, remain controversial topics. A host of recent reports challenge the notion that ROS decrease under hypoxia, and in fact suggest that an increase in ROS is necessary for some of the classic molecular responses to hypoxia in mammalian cells (see below) (17-21). Furthermore, Klimova and colleagues have observed an uncoupling of mitochondrial ROS and senescence (22). They found that decreasing mitochondrial ROS through the expression of anti-oxidant proteins was insufficient to inhibit senescence induced by hyperoxia in human lung fibroblasts (though inactivation of p53 and Rb did abrogate this response). What is unclear, though, is whether non-mitochondrial ROS are sufficient to induce senescence, highlighting the idea that the location of ROS is as important as overall levels. Along these lines, Yang and Hekimi have recently found that mutants in subunits of complex I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in C. elegans lead to increases in mitochondrial superoxide but not overall ROS levels, and can increase longevity. Mild treatment with the prooxidant paraquat also increases lifespan (23). Together these studies argue that the link between hyperoxia, ROS, and senescence is more complex than the classic model predicts and suggest low doses of ROS in the right place may even be beneficial to lifespan.

Oxygen and Molecular Adaptations

Hypoxia in cancer has been most well studied as a confounding factor in standard treatment regimens (24). Tumors that grow beyond a size of a few millimeters physically outgrow their normal blood supply and develop regions of hypoxia and hypoglycemia. This sets off a series of events that take advantage of normal cellular stress response machinery intended to relieve cells of their stressful environment through altered gene expression. The best understood of these responses is that of the hypoxia inducible factors (HIF), which comprise a family of hetrodimeric transcriptional regulators that target many genes associated with glucose metabolism, angiogenesis, and erythropoiesis, to name a few (25). The net result for normal tissues responding to hypoxia is increased tissue oxygenation and a return to homeostasis; neoplastic tissues however engage in a vicious cycle of growth and starvation. Hypoxia has been shown to increase tumor aggressiveness and metastasis, and is correlated with decreased survival in a host of different cancers (26).

Among the many genes regulated by the HIF proteins, a large subset is surprisingly associated with senescence (figure 2b). Such genes include cell cycle regulators, glycolytic enzymes, and a variety of secreted molecules. Interestingly, in spite of the observations that low oxygen reduces senescence, both genes that can promote and inhibit senescence are present in this group, suggesting that cell-type and context-specific responses are involved in determining whether certain signals will lead to senescence within a particular biological environment.

Hypoxia and cell cycle regulation

Hypoxia can induce cell cycle arrest in a variety of cell types. As for many stresses, though, it is the degree of hypoxia that is critical in determining the outcome. For example, reducing from atmospheric oxygen levels, primary fibroblasts undergo increased cell cycle progression (9, 10), until oxygen levels reach physiological hypoxia (on the order of 7.6 mm Hg). At that point and below, hypoxia induces a G1/S arrest that is dependent on HIF-1α mediated expression of the cell cycle regulators CDKN1A (p21) (27) and CDKN1B (p27) (28, 29), and HIF-1α mediated repression of CSC25A (30). Under anoxic conditions (<0.08 mm Hg), cell cycle arrest occurs in a HIF-1α independent manner, and at multiple points in the cell cycle (31, 32).

Interestingly, HIF-1α expression of many target genes occurs robustly at levels of oxygen (e.g. 15-50 mm Hg) that do not induce p21 or p27 (33), at which there are decreased levels of basal p53 compared to atmospheric oxygen (16), and at which cells demonstrate improved proliferation (9, 10). How then does HIF decide which target genes to activate and when (and thus whether to induce cell cycle arrest or not)? One possible mechanism to explain this dichotomy is the mechanism of gene regulation that HIF-1α employs on different genes. For example, expression of classic HIF-1α target genes (VEGF, GLUT1, PGK1, etc.) is dependent on sequence-specific binding of HIF-1α to hypoxia-responsive elements within promoter regions (34). Regulation of p21, however, has been attributed to a non-classical mechanism involving binding and displacement of Myc, which acts as a silencer in this case (27). Another possibility is that HIF-1α may target different genes through different mechanisms in different cell types. For example, recent evidence suggests that HIF-1α can activate TWIST in human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), leading to inhibition of p21 expression by displacement of E2A from the p21 promoter (35). Like primary fibroblasts, therefore, hypoxia in MSCs leads to evasion from senescence albeit via a different mechanism. Thus different gene regulation strategies may be employed by HIF-1α depending on the gene, the level of hypoxia, or the presence or absence of other cofactors within a given cell.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α can have opposing effects on the cell cycle and on cellular proliferation. The clearest example of this is in clear cell renal carcinoma, in which HIF-2α has been found to be a driver of tumor growth while HIF-1α may restrict proliferation (36, 37). At least one mechanism to explain this is that the HIF-α subunits differentially regulate the activity of c-Myc; HIF-1α antagonizes Myc while HIF-2α enhances Myc activity. It is unclear however whether these differences result in differences in for example p21 expression under hypoxia, or on the overall regulation of senescence in primary cells.

Hypoxia and metabolism

One of the classic adaptations that cells undergo when faced with decreased oxygen is the metabolic shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism. At the heart of this adaptation is HIF-1α -dependant transcriptional regulation of virtually all of the genes in the glycolytic pathway. These genes include the glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3, genes involved in glycolysis (PGI, PFK1, aldolase, TPI, GAPDH, PGK, PGM, enolase, PK, PFKFB1–4), and genes involved in decreasing mitochondrial function (PDK1 and MXI1) (for review, see (38)). In tumors, subjugation of this pathway even under non-hypoxic circumstances (the Warburg effect) is a common and tumor-promoting event (38).

In addition to providing an anaerobic source of ATP, glycolysis can also increase lifespan by decreasing oxidative stress. In support of this concept, both Phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI) and phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM) have been found in over-expression screens for genes that can bypass senescence, and depletion of these genes induces premature senescence (39). Thus another way that moderate hypoxia can suppress senescence is through the HIF-1α -mediated activation of the glycolytic pathway and concurrent inactivation of oxidative metabolism.

Hypoxia and SASP

Upon entering senescence cells demonstrate a number of characteristic phenotypic changes, including changes in cellular morphology and gene expression. These changes are what are commonly used to define the very state of senescence. One recent addition to the characterization of senescent cells is the observation that senescent cells display a unique secretory phenotype. This senescence-associated-secretory-phenotype ( SASP) includes the altered secretion of numerous inflammatory and immune-modulatory cytokines (such as IL-6, -7, and -8), growth and survival factors (such as GRO, HGF, and IGFBPs), and shed cell surface moleules (such as uPAR) (40). The effects of these changes are complex, and can conceivably promote both promalignant and prosenescent paracrine and autocrine responses.

The significance of a number of the proteins present in the SASP has been independently validated recently though genetic screens and other studies. For example, in order to identify the mechanisms of oncogene-induced and replicative senescence, Acosta et al. conducted a functional shRNA screen on human fibroblasts and looked for genes whose loss promoted bypass of senescence. They identified the chemokine receptor CXCR2 and its ligands IL-8 and GROα as critical mediators of senescence (41). A second group performed similar experiments to identify molecules essential for oncogenic B-Raf induced senescence and found an inflammatory network involving IL-6 and IL-8 (42). Finally, the plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI1), which has been used as a marker of senescence for several years, has recently been causatively linked to the induction of senescence downstream of p53 (43). PAI1 serves to inhibit the function of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator signaling through its receptor uPAR (44), and thus may be functionally similar to shedding of the receptor. All of these pathways have proven to be sufficient to induce senescence when activated.

Quite intriguingly, several of these genes are regulated by hypoxia in various systems. In particular, IL-8 and CXCR-2 have been found to be HIF-1α targets in prostate cancer cells (45), and GROα expression is increased in hypoxic pulmonary arteries (46). IL-6 is upregulated in chronically hypoxic carotid bodies (47), and PAI1 is a direct target of HIF-1α in many different cell-types (48-51). Thus once again, numerous pro-senescent pathways may be regulated by hypoxia and HIF-1α depending on the proper context.

Hypoxia and p53

A central mediator of senescence is the p53 tumor suppressor, a multifunctional transcription factor that is responsible for effecting cell cycle arrest and cell death programs downstream of a host of stimuli. One of these stimuli is hypoxia, although the level of hypoxia required to activate p53 is generally significantly more severe than that which is sufficient to induce HIF-1α (near anoxia for p53) (52). Even under mildly hypoxic conditions, however, when a cell is exposed to a p53-inducing genotoxic stess, an interaction between HIF-1α and p53 would have the potential to regulate senescence. Indeed, there are numerous reports which describe means by which components of these two pathways interact.

At the direct level, protein-protein interactions between p53 and HIF-1α have been described, which in general seem to promote p53 stabilization or HIF-1α degradation (53-58). Likely, maintaining p53 expression would have a pro-senescent effect. Indirectly, targets of each of p53 and HIF-1α have been found to cross-regulate each other. For example, the p53 target PML, which itself is both necessary and sufficient to induce senescence (59, 60), has been found to negatively regulate the translation of HIF-1α through the suppression of mTOR (61). Conversely, the HIF-1α target MIF can bind to p53 directly (62, 63) and inhibit many p53-dependent responses (64-67), senescence included (15). Collectively, p53 and HIF-1α demonstrate a number of mechanisms in which they act in opposing manners.

Hypoxia and telomerase

Senescence was, of course, first appreciated by Hayflick and colleagues, who observed that primary human cells proliferate for a finite period of time before arresting (68, 69). It wasn't until decades later, though, that it became clear that the root of this arrest was the shortening of telomeres that induced senescence (reviewed in (70)). In this light the observation that low oxygen can increase cellular lifespan raises the issue of the regulation of telomere length. Indeed another HIF-1α target is the telomerase active subunit hTERT (71, 72); and this mode of regulation has been hypothesized to be involved in cancer development. Recently, Bell et al. demonstrated that upregulation of telomerase by hypoxia could extend the lifespan of human fibroblasts by 10 population doublings (73), which is in accordance with the early observations by Packer and Fuehr that hypoxia can extend the lifespan of primary fibroblasts (9). Here again hypoxia acts to inhibit the senescent response.

Hypoxia and OIS

Perhaps the most important implication of regulation of senescence by hypoxia is the impact on tumor suppression. Oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) plays a critical role in tumor suppression, acting as a fail-safe mechanism to avert inappropriate proliferation. Senescent cells remain permanently in a state of cell-cycle arrest that is enforced by the p53 and pRb tumor suppressor pathways. In primary human fibroblasts, for example, OIS by overexpression of H-Ras is induced rapidly following oncogene expression, and is associated with the accumulation of p53 and p16 (74). Results such as these have been reported for many different oncogenes in different cell types.

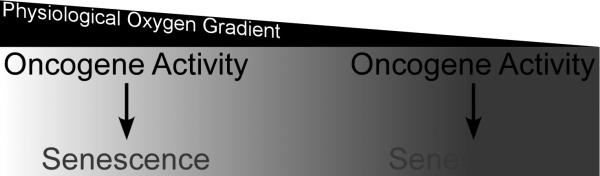

As mentioned, however, senescence due to H-Ras expression is dependent on ROS production and rescued under low oxygen conditions (~23 mm Hg) (8) that interestingly are within the range of normal for many tissues (figure 1). So how relevant is a tumor suppressor response that may be inhibited under certain in vivo conditions due to a tolerable oxygen environment? Is there tissue specificity to senescence due to tissue oxygenation? Are there microenvironments within tissues that are permissive to cells that would otherwise senesce? The answers may be drawn from the fact that the stress associated with culturing cells in atmospheric conditions (as well as other effects of “culture shock” (75)) contributes to the in vitro promotion of senescence. The same oncogenic mutation therefore may not induce senescence under physiological conditions in vivo in the absence of other signals or stresses (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Oxygen gradients regulate senescence such that within the physiological range of oxygen, a similar oncogenic stimulus may or may not induce senescence. As these gradients are different in different tissues, oxygen levels may contribute to tissue selectivity of oncogenesis.

One clinical manifestation that would support this concept is the melanocytic nevus, a benign tumor of melanocytes that is filled with cells that frequently harbors a mutation in the BRaf gene (76). BRaf, much like H-Ras and other potent oncogenes, induces senescence in cells in culture (77). Additionally, BRaf mutations can induce senescence in a physiological setting, in which Micholanglou et al. have observed robust senescent staining throughout specimens of nevi. This phenotype has also been modeled in mice (78). What is relevant about this example is that parts of the skin are mildly to severely hypoxic, with oxygen tensions in the dermis near 76 mm Hg, the epidermis ranging down to roughly 3.8 mm Hg, and portions of the sebaceous glands and hair follicles near anoxia (79). Melanocytes normally reside at the epidermal/dermal junction, and nevi often grow into the epidermis. So in this context, if a BRaf mutation occurs and induces senescence, how do nevi manifest fields of senescent cells? One possibility is that melanocytes with active BRaf continue to proliferate for some time (potentially promoted by the low oxygen environment in which they reside) before some other signal induces them to senesce. In this respect, in vivo conditions support the propagation of oncogene-activated cells.

An experimental model that provides another example is the case of loss of the VHL tumor suppressor. Recent studies have demonstrated that loss of VHL in mouse fibroblasts induces senescence in a pRb dependent manner (80). VHL is particularly relevant for this discussion, as it is the primary regulator of the HIF-α subunits under oxic conditions, directing proteasome-mediated degradation that inactivates HIF function (81). Loss of VHL has been found to induce senescence in a HIF-independent manner, through the regulation of p400 and p27, which promote the ability of pRB to effect cell cycle arrest and senescence (80). Furthering these studies, however, we have recently demonstrated that moderate hypoxia can again deactivate this senescence response (16). Additionally, loss of VHL in renal epithelia in vivo, where oxygen tensions are mildly to moderately hypoxic (~10-50mm Hg (82)) is insufficient to induce senescence, but does increase sensitivity to oxidizing agents such as paraquat, resulting in a robust senescent response when VHL loss is coupled with oxidative stress. These findings reinforce the idea that what has been typically been shown to induce senescence in atmospheric conditions in vitro, may be insufficient to do so in vivo due to the lower oxygen tension.

Summary

In addition to the well-established impact of hypoxia on tumor aggressiveness and therapy, recent findings suggest that normal tissue hypoxia can impact a primary response to tumor initiation, cellular senescence. These observations underscore the importance of studying biological processes in appropriate physiological conditions. At the molecular level, hypoxic activation of the HIF pathway can affect several mediators of senescence in complex ways, such that conflicting signals conceivably can be sent simultaneously. This is probably best demonstrated by the apparent opposing induction of p21 by HIF in numerous transformed or tumor cell lines, versus the downregulation of p53 and thereby p21 in primary cells. What distinguishes these two responses is critical for understanding the complexities of HIF biology and stress responses. At a larger level, however, these observations challenge the established models of what is sufficient to induce senescence in a physiological setting and remind us that experimental interpretations need to take into consideration the various contextual influences that may affect the senescence/survival balance. Moderate hypoxia, which is common throughout the body, has the potent effect of preventing the onset of senescence due to many well-studied stimuli.

An interesting corollary to this is that within tissues oxygen gradients often exist, with stem cells residing in the most hypoxic regions (83). It is tempting to think then that these cells, which are known to be more resistant to oxidative stress as a mechanism of self-preservation (84, 85), benefit from their hypoxic environments by avoiding senescence, which would be detrimental to the regenerative capacity of the tissue. These regions would also then be hypothetically more susceptible to oncogenic transformation, in support of some aspects of the tumor stem cell theory. From a therapeutic point of view, modulating tumor hypoxia may benefit not only classical treatment approaches, but may also allow reinstatement of the tumor suppressor function of senescence. Hopefully, further investigations along these lines will help illuminate what mechanisms drive cells to overcome this barrier to tumor development, and also aid in attempts to curb tumor progression through improved therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgement

S.M.W. is funded by the Ohio Cancer Research Associates. A.J.G. is funded by CA088480 from the NCI.

References

- 1.Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. The signals and pathways activating cellular senescence. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:961–976. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng Y, Chan SS, Chang S. Telomere dysfunction and tumour suppression: the senescence connection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:450–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Micco R, Fumagalli M, Cicalese A, Piccinin S, Gasparini P, Luise C, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature. 2006;444:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature05327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agger K, Cloos PA, Rudkjaer L, Williams K, Andersen G, Christensen J, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase JMJD3 contributes to the activation of the INK4A-ARF locus in response to oncogene- and stress-induced senescence. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1171–1176. doi: 10.1101/gad.510809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barradas M, Anderton E, Acosta JC, Li S, Banito A, Rodriguez-Niedenfuhr M, et al. Histone demethylase JMJD3 contributes to epigenetic control of INK4a/ARF by oncogenic RAS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1177–1182. doi: 10.1101/gad.511109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Docke W, Lotze C. Mild hyperoxia shortens telomeres and inhibits proliferation of fibroblasts: a model for senescence? Exp Cell Res. 1995;220:186–193. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AC, Fenster BE, Ito H, Takeda K, Bae NS, Hirai T, et al. Ras proteins induce senescence by altering the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7936–7940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Packer L, Fuehr K. Low oxygen concentration extends the lifespan of cultured human diploid cells. Nature. 1977;267:423–425. doi: 10.1038/267423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–747. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuttle SW, Maity A, Oprysko PR, Kachur AV, Ayene IS, Biaglow JE, et al. Detection of reactive oxygen species via endogenous oxidative pentose phosphate cycle activity in response to oxygen concentration: implications for the mechanism of HIF-1alpha stabilization under moderate hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36790–36796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan H, Kaneko T, Matsuo M. Relevance of oxidative stress to the limited replicative capacity of cultured human diploid cells: the limit of cumulative population doublings increases under low concentrations of oxygen and decreases in response to aminotriazole. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;81:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01584-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q, Ames BN. Senescence-like growth arrest induced by hydrogen peroxide in human diploid fibroblast F65 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4130–4134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Q, Fischer A, Reagan JD, Yan LJ, Ames BN. Oxidative DNA damage and senescence of human diploid fibroblast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4337–4341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welford SM, Bedogni B, Gradin K, Poellinger L, Broome Powell M, Giaccia AJ. HIF1alpha delays premature senescence through the activation of MIF. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3366–3371. doi: 10.1101/gad.1471106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welford SM, Dorie MJ, Li X, Haase VH, Giaccia AJ. Renal oxygenation suppresses VHL loss-induced senescence that is caused by increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4595–4603. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01618-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klimova T, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial complex III regulates hypoxic activation of HIF. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:660–666. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunelle JK, Bell EL, Quesada NM, Vercauteren K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, et al. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, et al. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25130–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, et al. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansfield KD, Guzy RD, Pan Y, Young RM, Cash TP, Schumacker PT, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-alpha activation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klimova TA, Bell EL, Shroff EH, Weinberg FD, Snyder CM, Dimri GP, et al. Hyperoxia-induced premature senescence requires p53 and pRb, but not mitochondrial matrix ROS. Faseb J. 2009;23:783–794. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang W, Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatum JL, Kelloff GJ, Gillies RJ, Arbeit JM, Brown JM, Chao KS, et al. Hypoxia: importance in tumor biology, noninvasive measurement by imaging, and value of its measurement in the management of cancer therapy. Int J Radiat Biol. 2006;82:699–757. doi: 10.1080/09553000601002324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–634. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koshiji M, Kageyama Y, Pete EA, Horikawa I, Barrett JC, Huang LE. HIF-1alpha induces cell cycle arrest by functionally counteracting Myc. Embo J. 2004;23:1949–1956. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner LB, Li Q, Park MS, Flanagan WM, Semenza GL, Dang CV. Hypoxia inhibits G1/S transition through regulation of p27 expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7919–7926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goda N, Ryan HE, Khadivi B, McNulty W, Rickert RC, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is essential for cell cycle arrest during hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:359–369. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.359-369.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammer S, To KK, Yoo YG, Koshiji M, Huang LE. Hypoxic suppression of the cell cycle gene CDC25A in tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1919–1926. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.15.4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green SL, Freiberg RA, Giaccia AJ. p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1) regulate cell cycle reentry after hypoxic stress but are not necessary for hypoxia-induced arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1196–1206. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1196-1206.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammond EM, Green SL, Giaccia AJ. Comparison of hypoxia-induced replication arrest with hydroxyurea and aphidicolin-induced arrest. Mutat Res. 2003;532:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang BH, Rue E, Wang GL, Roe R, Semenza GL. Dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation properties of hypoxia- inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17771–17778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai CC, Chen YJ, Yew TL, Chen LL, Wang JY, Chiu CH, et al. Hypoxia inhibits senescence and maintains mesenchymal stem cell properties through downregulation of E2A-p21 by HIF-TWIST. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-287508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu CJ, Diehl JA, Simon MC. HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordan JD, Lal P, Dondeti VR, Letrero R, Parekh KN, Oquendo CE, et al. HIF-alpha effects on c-Myc distinguish two subtypes of sporadic VHL-deficient clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denko NC. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:705–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kondoh H, Lleonart ME, Gil J, Wang J, Degan P, Peters G, et al. Glycolytic enzymes can modulate cellular life span. Cancer Res. 2005;65:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Munoz DP, Goldstein J, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acosta JC, O'Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kortlever RM, Higgins PJ, Bernards R. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a critical downstream target of p53 in the induction of replicative senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:877–884. doi: 10.1038/ncb1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McMahon B, Kwaan HC. The plasminogen activator system and cancer. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2008;36:184–194. doi: 10.1159/000175156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maxwell PJ, Gallagher R, Seaton A, Wilson C, Scullin P, Pettigrew J, et al. HIF-1 and NF-kappaB-mediated upregulation of CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression promotes cell survival in hypoxic prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:7333–7345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burke DL, Frid MG, Kunrath CL, Karoor V, Anwar A, Wagner BD, et al. Sustained hypoxia promotes the development of a pulmonary artery-specific chronic inflammatory microenvironment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L238–250. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90591.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X, He L, Stensaas L, Dinger B, Fidone S. Adaptation to chronic hypoxia involves immune cell invasion and increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in rat carotid body. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L158–166. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90383.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fink T, Kazlauskas A, Poellinger L, Ebbesen P, Zachar V. Identification of a tightly regulated hypoxia-response element in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Blood. 2002;99:2077–2083. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kimura D, Imaizumi T, Tamo W, Sakai T, Ito K, Hatanaka R, et al. Hypoxia enhances the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human lung cancer cells, EBC-1. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2002;196:259–267. doi: 10.1620/tjem.196.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koong AC, Denko NC, Hudson KM, Schindler C, Swiersz L, Koch C, et al. Candidate genes for the hypoxic tumor phenotype. Cancer Res. 2000;60:883–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato M, Tanaka T, Maemura K, Uchiyama T, Sato H, Maeno T, et al. The PAI-1 gene as a direct target of endothelial PAS domain protein-1 in adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:209–215. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0296OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammond EM, Denko NC, Dorie MJ, Abraham RT, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia links ATR and p53 through replication arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1834–1843. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1834-1843.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravi R, Mookerjee B, Bhujwalla ZM, Sutter CH, Artemov D, Zeng Q, et al. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Genes Dev. 2000;14:34–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.An WG, Kanekal M, Simon MC, Maltepe E, Blagosklonny MV, Neckers LM. Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Nature. 1998;392:405–408. doi: 10.1038/32925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen D, Li M, Luo J, Gu W. Direct interactions between HIF-1 alpha and Mdm2 modulate p53 function. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13595–13598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blagosklonny MV, An WG, Romanova LY, Trepel J, Fojo T, Neckers L. p53 inhibits hypoxiainducible factor-stimulated transcription. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11995–11998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.11995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanchez-Puig N, Veprintsev DB, Fersht AR. Binding of natively unfolded HIF-1alpha ODD domain to p53. Mol Cell. 2005;17:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansson LO, Friedler A, Freund S, Rudiger S, Fersht AR. Two sequence motifs from HIF-1alpha bind to the DNA-binding site of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10305–10309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122347199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Stanchina E, Querido E, Narita M, Davuluri RV, Pandolfi PP, Ferbeyre G, et al. PML is a direct p53 target that modulates p53 effector functions. Mol Cell. 2004;13:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferbeyre G, de Stanchina E, Querido E, Baptiste N, Prives C, Lowe SW. PML is induced by oncogenic ras and promotes premature senescence. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2015–2027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernardi R, Guernah I, Jin D, Grisendi S, Alimonti A, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR. Nature. 2006;442:779–785. doi: 10.1038/nature05029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jung H, Seong HA, Ha H. Direct interaction between NM23-H1 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is critical for alleviation of MIF-mediated suppression of p53 activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32669–32679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jung H, Seong HA, Ha H. Critical role of cysteine residue 81 of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in MIF-induced inhibition of p53 activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20383–20396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hudson JD, Shoaibi MA, Maestro R, Carnero A, Hannon GJ, Beach DH. A proinflammatory cytokine inhibits p53 tumor suppressor activity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1375–1382. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fingerle-Rowson G, Petrenko O, Metz CN, Forsthuber TG, Mitchell R, Huss R, et al. The p53-dependent effects of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9354–9359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petrenko O, Fingerle-Rowson G, Peng T, Mitchell RA, Metz CN. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency is associated with altered cell growth and reduced susceptibility to Ras-mediated transformation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11078–11085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nemajerova A, Mena P, Fingerle-Rowson G, Moll UM, Petrenko O. Impaired DNA damage checkpoint response in MIF-deficient mice. Embo J. 2007;26:987–997. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hayflick L. The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stewart SA, Weinberg RA. Senescence: does it all happen at the ends? Oncogene. 2002;21:627–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nishi H, Nakada T, Kyo S, Inoue M, Shay JW, Isaka K. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates upregulation of telomerase (hTERT). Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6076–6083. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.6076-6083.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yatabe N, Kyo S, Maida Y, Nishi H, Nakamura M, Kanaya T, et al. HIF-1-mediated activation of telomerase in cervical cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:3708–3715. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Schumacker PT, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent extension of the replicative life span during hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5737–5745. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02265-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sherr CJ, DePinho RA. Cellular senescence: mitotic clock or culture shock? Cell. 2000;102:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CM, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dhomen N, Reis-Filho JS, da Rocha Dias S, Hayward R, Savage K, Delmas V, et al. Oncogenic Braf induces melanocyte senescence and melanoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Evans SM, Schrlau AE, Chalian AA, Zhang P, Koch CJ. Oxygen levels in normal and previously irradiated human skin as assessed by EF5 binding. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2596–2606. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Young AP, Schlisio S, Minamishima YA, Zhang Q, Li L, Grisanzio C, et al. VHL loss actuates a HIF-independent senescence programme mediated by Rb and p400. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:361–369. doi: 10.1038/ncb1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ohh M, Park CW, Ivan M, Hoffman MA, Kim TY, Huang LE, et al. Ubiquitination of hypoxiainducible factor requires direct binding to the beta-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:423–427. doi: 10.1038/35017054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brezis M, Rosen S. Hypoxia of the renal medulla--its implications for disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:647–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eliasson P, Jonsson JI. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: low in oxygen but a nice place to be. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:17–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, Matsuoka S, Takubo K, Hamaguchi I, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature02989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tothova Z, Kollipara R, Huntly BJ, Lee BH, Castrillon DH, Cullen DE, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]