Abstract

Introduction

Examine psychological functioning and beliefs about medicine in adolescents with HIV-1 on HAART in a community-based directly observed therapy (DOT) pilot feasibility study.

Methods

Youth with behaviorally-acquired HIV (n=20; 65% female; median age 21 years) with adherence problems, received once-daily DOT. Youth were assessed at baseline, week 12 (post-DOT) and week 24 (follow-up).

Results

Baseline to week 12 comparisons: 55% of youth reported clinical depressive symptoms compared to 27% at week 12 with sustained improvements at week 24. Substance use: Borderline clinical range (Tscore=68), with clinical but statistically non-significant improvement (Tscore=61). Hopelessness scores reflected optimism for the future. Coping strategies showed significantly decreased Cognitive Avoidance (p=0.02), Emotional Discharge (p=0.004), and Acceptance/Resignation (“nothing I can do,” p=0.004); Positive Reappraisal and Seeking Support emerged. Aside from depressive symptoms, week 12 improvements were not sustained at week 24. DOT adherence was predicted by higher baseline depression (p=0.05), Beliefs About Medicine (p=0.006) and Perceived Threat of illness scores (p=0.03).

Discussion

Youth with behaviorally-acquired HIV and adherence problems who participated in a community-based DOT intervention reported clinically improved depressive symptoms, and temporarily reduced substance use and negative coping strategies. Depressive symptoms, Beliefs About Medicine and viewing HIV as a threat predicted better DOT adherence.

Keywords: HIV, adolescent, psychological functioning, directly observed therapy (DOT), adherence

INTRODUCTION

Poor adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is associated with increased mortality [1] and remains a challenge in HIV management, especially in youth with behaviorally acquired HIV. Barriers to adherence for youth with HIV include psychological functioning, substance use, and beliefs about medication [2, 3].

Directly observed therapy (DOT) for adults with HIV demonstrated mixed findings and experience in pediatric and adolescent medical populations is limited. Successful HAART adherence through DOT would provide better HIV disease control, reduce risk of transmission, and potentially prevent development and spread of viral resistance.

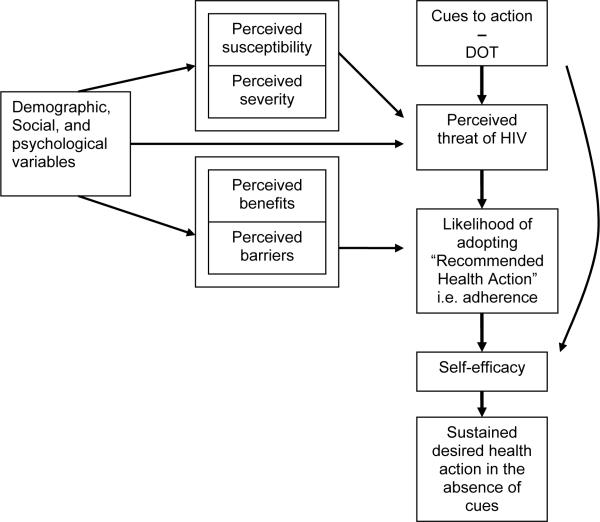

Previous DOT studies utilized a Medical Model, which fails to address psychosocial influences on adherence. This study utilized combined aspects of the Health Beliefs Model (HBM) [4] and Self-Efficacy Theory [5] (Figure 1). HBM [4] posits the determinants of adopting a behavior change are the perceived threat of disease and whether benefits outweigh barriers to adopting the behavior. A cue to action [4] also is required (e.g., DOT). Thus, adolescents will respond to the perceived threat of AIDS by adhering to HAART through DOT, resulting in enhanced belief in his/her ability (self-efficacy) to adhere and sustain adherence when tempted not to (barrier). Self-efficacy is enhanced when adherence is maintained as the cue to action (DOT) is gradually reduced and ultimately discontinued [4,5].

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of DOT − Health Beliefs Model + Self-Efficacy Theory

Psychological factors assessed within a community-based DOT pilot feasibility study in youth with HIV previously non-adherent to HAART are reported. Within the HBM-Self Efficacy framework, we hypothesized DOT participation would improve coping strategies around barriers to adherence, enhance self-efficacy, reduce depressive symptoms, and improve adherence.

METHODS

Primary outcomes of this 4-site, 24-week pilot study (Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 1036B) examining acceptability and feasibility of community-based DOT in youth with HIV are reported elsewhere [6]. Secondary aims, reported herein, included assessment of depression, hopelessness, emotional and behavioral problems, substance use, coping style, and beliefs about medication at baseline, week 12 (post-DOT) and week 24 (follow-up). The protocol was Institutional Review Board approved with written consent obtained per respective institutional guidelines.

Participants

Youth, age 16–24 years, with HIV acquired via high-risk behavior with documented adherence problems continuing, re-initiating, or changing HAART.

Psychological Assessment Instruments

All instruments have established reliability and validity [7–11] and were administered via interview to assure comprehension and completeness.

Depression

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II) [7].

Coping

Coping Responses Inventory (CRI) [8]. Youth were instructed to respond to “Difficulty adhering to HIV medications as prescribed.”

Hopelessness

Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) [9].

Emotional and Behavioral Problems

Adult Self-Report (ASR) [10]. Contains Internalizing and Externalizing scales, 8 clinical subscales, alcohol and substance use frequency.

Beliefs About Medicine

Beliefs About Medicine Scale (BAMS) [11]. Four subscales: Perceived Threat; Positive Outcome Expectancy; Negative Outcome Expectancy; Intent (proxy for self-efficacy). Except for Negative Outcome Expectancy, higher scores reflect positive outcomes.

Analyses

DOT “success” was defined as >90% DOT visit adherence with successful weaning to self-administered therapy (SAT) [6]. Week 12 and 24 outcome comparisons to Baseline used Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Adherent versus non-adherent comparisons used Fisher's Exact Test. Univariate logistic regression identified predictors of adherence to DOT. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 [12].

RESULTS

Twenty youth enrolled between April 2006–2007 (median age 21years (range, 18–24), primarily female (65%), African American (75%; Hispanic, 20%), high school graduate (75%), unemployed (75%), with documented mental health diagnosis 55% (depressive disorder 50%)). Youth reported frequent (≥4 times/week) use of alcohol (10%) and marijuana (40%), but no intravenous drug use. Participants initiated HAART a median of two years (range 0–7.5 years) prior to enrollment; 45% were receiving HAART at entry. Median CD4 count was 227 cells/mm3 (range, 10–443); median viral load was 4.61 log10 copies/mL (range, 1.04–5.75).

Reported adherence barriers included problems with medical insurance (20%) and transportation to keep clinic appointments (15%) or pick up medications (10%). Of those on HAART, forgetting, worrying people would find out about their HIV, and falling asleep before taking their medications were reported by 44% respectively as frequent (≥1–2 times/week) reasons for non-adherence; 55% reported needing a break from medications.

Earliest complete transition from DOT to SAT was week 12. Week 12 median DOT visit adherence was 83%. Six participants were DOT successes; three sustained >93% SAT medication adherence at week 24.

Psychological functioning outcomes are shown in Table 1. No assessed behavioral domain emerged as clinically or statistically significant. Primary coping mechanisms reported at baseline included Cognitive Avoidance (55%), Emotional Discharge (25%), and Seeking Alternative Reward (20%). A secondary coping mechanism, Acceptance/Resignation, significantly decreased at week 12. Youth viewed HIV as a threat, held positive outcome expectations (benefits), lower negative outcome expectations (consequences), and high positive intentions (self-efficacy), which associated with adherence to DOT.

Table 1.

Psychological Outcomes: Baseline Comparisons to Week 12 and Week 24.

| Variable | Baseline (n=20) | Week 12 (n=14) | p-value1 | Week 24 (n=12) | p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression BDI-II Total Score, Clinical range n(%) | 11(55) | 4(27) | 0.23* | 4(33) | 0.40* |

| Mild range n (%) | 6 (30) | 1(7) | - | 1 (8) | - |

| Moderate range n (%) | 4 (20) | 2 (13) | 2 (17) | - | |

| Severe range n (%) | 1 (5) | 1(7) | 1 (8) | - | |

| Hopelessness Total Score3 (Mdn) | 3 | 1 | 0.10 | 2.5 | 0.78 |

| Clinically At-Risk (score ≥9) n (%) | 2(10) | 1(7) | - | 1(8) | - |

| Emotional/Behavioral Functioning (ASR) ** | - | - | - | - | |

| #Days Substance Use/Frequency | 68 | 61 | 0.24* | 65 | 0.67 |

| Primary Coping Style *** | |||||

| Cognitive Avoidance (Mdn T-score) | 67 | 58 | 0.02 | 65 | 0.79 |

| Emotional Discharge (Mdn T-score) | 63 | 53 | 0.004 | 56 | 0.12 |

| Seek Alternate Reward (Mdn T-score) | 58 | 51 | 0.29 | 56 | 0.65 |

| Acceptance Resignation (Mdn T-score) | 55 | 45 | 0.004 | 52 | |

| Positive Reappraisal n (%) | - | 3 (21) | - | 1(7) | - |

| Seek Support n (%) | - | 5 (7) | - | 1(8) | - |

| Beliefs About Medicine (BAMS) | |||||

| Perceive Threat of Illness (Mdn, range) | 45.5 (15–71) | 42 (22–61) | 0.61 | 46 (19–55) | 0.77 |

| Positive Outcome Expectation (Mdn, range) | 119.5 (64–136) | 124 (103–140) | 0.16 | 124 (86–140) | 0.21 |

| Negative Outcome Expectation (Mdn, range) | 37.5 (13–71) | 26 (13–45) | 0.21 | 31 (16–52) | 0.61 |

| Intent (Mdn, range) | 47.5 (37–49) | 45 (7–49) | 0.39 | 46 (37–49) | 0.57 |

| Total Score (Mdn, range) | 276 (156–315) | 277 (205–277) | 0.73 | 265 (233–314) | 0.61 |

Baseline to Week 12 Comparison

Baseline to Week 24 Comparison

Statistically non-significant, but clinically significant change

Reported scores in minimal clinical range; Total score ≥9 indicates clinical risk.

T-score, M=50, SD=10; Borderline Clinical Significance = 65–69; Clinical Significance ≥70; No domain/subdomain clinically/statistically significant

T-score, M=50, SD=10; 41–45=somewhat<avg., 46–54=avg., 55–59=somewhat>avg., 60–65 well>avg, ≥66 considerably>avg.

- Not applicable, N/A

Although not statistically significant, clinical improvements in depression scores and substance use/number of days used were observed at week 12. Aside from depressive symptoms, no other week 12 improvements were sustained. BAMS scores remained consistent over time.

Predictors of Adherence to DOT

Baseline predictors of DOT adherence included: Higher depression score (OR=1.15, CI95 0.98–1.35, p=0.046), higher BAMS Total score (OR=1.08, CI95 1.00–1.17, p=0.006), and higher BAMS Perceived Threat of Illness score (OR=1.09, CI95 1.00–1.20, p=0.03).

DISCUSSION

This community-based DOT pilot study designed for youth with HIV with known HAART adherence difficulties demonstrated feasibility and acceptability (details and health outcomes reported elsewhere) [6]. Secondary aims assessed psychosocial factors and identified barriers to and potential predictors of DOT adherence. Following DOT, clinically improved depressive symptoms, relatively decreased substance use, reduced passive coping strategies, and new active coping practices were observed. Greater baseline depressive symptoms, global Beliefs About Medicine and perceiving HIV as a threat predicted DOT adherence.

This cohort generally reported optimism for their future. Despite identifying HIV as a threat, youth endorsed general positive health outcome expectation. Although acknowledging negative consequences associated with medication adherence, youth expressed high self-efficacy (intent) to adhere. No change in these domains over time (sustained hope, positive health outcome expectation and self-efficacy in relation to adherence despite continued perceived threat of HIV), combined with the identified DOT predictors, support the proposed HBM- Self-Efficacy framework upon which this study was based.

Although the observed improvement in post-DOT depressive symptoms was not statistically significant, it was clinically significant, suggesting a potential indirect benefit of daily DOT interaction. Thus, DOT may be well-suited to youth with co-morbid HIV and clinical depression.

DOT participation was associated with temporarily reduced avoidant coping behaviors and emotional discharge, while introducing problem-approach strategies (positive reappraisal and seeking support) in relation to adherence, suggesting a potential shift in appraisal of their disease (able to do something about it) and means by which to better manage it. Neither improvements in depression nor coping style associated with improved HAART adherence alone.

Study Limitations

Results are limited by the high discontinuation rate, as well as factors inherent with small sample size, and may not generalize to all youth with HIV. Psychological outcomes were reliant on self-report, subject to response bias and inability to verify accuracy. Nonetheless, significant findings are robust and should strengthen with increased sample size.

CONCLUSIONS

DOT appears to provide potential benefits for youth with HIV beyond improving adherence alone, especially for youth presenting with depression. While youth view HIV as a threat, other factors present as barriers to HAART adherence, despite perceived benefit of adherence and self-efficacy to adhere. DOT provides a multi-level intervention that addresses psychosocial factors, including coping strategies, which previously may have served as barriers to adherence. Outcomes of DOT with adolescents with HIV are promising and further investigation in a larger scale study is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C).

We extend our gratitude to the patients who participated in this study and provided us with their invaluable feedback and the participating sites and their site staff who made this study possible. We would like to especially acknowledge the DOT facilitators who were the arms, eyes and ears of this study and who worked tirelessly to support the study participants. We also appreciate the guidance provided by Helen Lowenthal, MSW and Jennifer Mitty, MD, Brown University, Providence, RI based on their experience providing DOT to HIV infected adults. The authors also thank Kristen A. Reikert, PhD, for granting permission to use and providing the Beliefs About Medicine Scale for this study. Lastly the contribution of each member of the protocol 1036B team is acknowledged and appreciated.

Participating sites: Children's Hospital of Michigan – Brianne Moore (DOT facilitator), Charnell Cromer (Study coordinator), Kathryn Wright MD (PI) and Elizabeth Secord MD (investigator)

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital – Joyce Fields and Abby Verbist (DOT facilitators), Jill Utech (Study coordinator), Aditya Gaur (PI)

University of Southern California, LA and Children's Hospital of LA –Roman Hernandez (DOT facilitator), Cathy Salata and Cecilia Lind (Study coordinators), Michael Neely MD (PI)

University of California, San Diego – Roberto “Hugo” Escudero (DOT facilitator), Kim Norris (study coordinator), Stephen Spector MD (PI)

P1036B Project Team: Protocol Chair – Aditya Gaur, MD

Protocol Vice Chairs – Patricia Flynn, MD; Marvin Belzer, MD

Protocol Psychologist – Patricia Garvie, PhD

NICHD Medical Officer – Bill G. Kapogiannis, MD; Audrey Rogers, MD, MPH

Investigators – George McSherry, MD; Patricia Emmanuel, MD

Clinical Trials Specialist – Kimberly Hudgens, MSHCA and Emily Demske

Protocol Statistician – Chengcheng Hu, PhD; Paula Britto, MS

Data Manager – Bobbie Graham, BS; Mary Caporale, MSc, MPH

DAIDS Medical Officer – Karin Klingman, MD

Protocol Virologist – Stephen Spector, MD

Field Representative – Jean Kaye, RN

Westat Representative – Marsha Johnson, RN, BSN/

Protocol Pharmacist – Lynette Purdue, PharmD

Laboratory Technologist – Bill Kabat, BS

Laboratory Data Coordinator – Heather Sprenger, MS

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- ASR

Adult Self-Report

- BAMS

Beliefs About Medicine Scale

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Ed.

- BHS

Beck Hopelessness Scale

- CRI

Coping Responses Inventory

- DOT

Directly Observed Therapy

- HAART

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HBM

Health Beliefs Model

- PACTG

Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group

- SAT

Self-Administered Therapy

- VL

Viral Load

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR, et al. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Apr 15;50(5):529–36. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819675e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Murphy DA, Sarr M, Durako SJ, Moscicki AB, Wilson CM, Muenz LR. Barriers to HAART adherence among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Mar;157(3):249–55. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, Muenz L, Ellen J. Prevalence and Interactions of Patient-Related Risks for Nonadherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Youth in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010 Feb;24(2):97–104. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984 Spr;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977 Mar;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gaur AH, Belzer M, Britto P, et al. Directly Observed Therapy for Non-adherent HIV-Infected Adolescents - Lessons Learned, Challenges Ahead. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2010 Sep;26(9):947–53. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. Second Edition Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Moos RH. Coping Responses Inventory - Adult Form Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Lutz, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Hopelessness Scale. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Reikert KA, Drotar D. Beliefs about medicine scale: Development, reliability and validity. J Clin Psychol Med S. 2002;9(2):177–84. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Statistical Analysis System. SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC: 2005. [Google Scholar]