Abstract

Dialysate calcium (Ca) concentration should be viewed as part of the integrated therapeutic regimen to control renal osteodystrophy and maintain normal mineral metabolism. The goals of this integrated approach are to keep the patient in a mild positive Ca mass balance (CaMB), to maintain normal serum Ca levels, to control plasma parathyroid hormone values to two to three times above normal levels, and to avoid soft-tissue calcifications. Thus, a correct net CaMB during hemodialysis (HD) is crucial in the treatment of renal osteodystrophy. Very few studies have been published which measured CaMBs in bicarbonate HD. This is mainly due to the technical difficulties in achieving an accurate measurement of CaMBs owing to the need for the collection of the total spent dialysate or of a proportional aliquot of it. Whereas no doubt exists about the fact that an inlet dialysate Ca concentration (CaD) of 1.75 mmol/L leads to a positive CaMB, more controversial is this issue, when dealing with a CaD of 1.50 mmol/L and, even more, when dealing with a CaD of 1.25 mmol/L. Another important issue is the appropriate CaD in long-hour slow-flow nocturnal HD. Finally, which CaMB should we study: ionized CaMB or total CaMB? This issue is largely discussed in the review.

Disturbances in mineral and bone metabolism are highly prevalent and are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among chronic kidney disease patients. To address this issue, current guidelines recommend a number of therapeutic strategies, such as the use of phosphate binders, vitamin D analogues, or calcimimetics [1]. However, in current practice, little attention is paid to the dialysate calcium (Ca) concentration. On the contrary, it should be viewed as part of the integrated therapeutic regimen to control renal osteodystrophy and maintain normal mineral metabolism. The goals of this integrated approach are to keep the patient in a mild positive Ca mass balance (CaMB), to maintain normal serum Ca levels, to control plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) values from two to three times above normal levels, and to avoid soft-tissue calcifications [2]. Thus, a correct net CaMB during hemodialysis (HD) is crucial in the treatment of renal osteodystrophy.

CaMB during HD is influenced by both diffusive and convective transport. The driving force which determines the diffusive transport is given mainly by the inlet dialyzer diffusion concentration gradient between the ionized calcium (iCa) levels in the dialysate and in the plasma water. It is expressed as

| (1) |

where 1.12 is the Gibbs-Donnan factor [3, 4].

CaMB is influenced also by the convective transport. CaMBs, which can be expressed as iCaMBs and total CaMBs, (tCaMBs) can be calculated as follows (tCaMB is taken as an example):

| (2) |

Solute removal during dialysis is expressed as a negative number, whereas solute gain is expressed as a positive number.

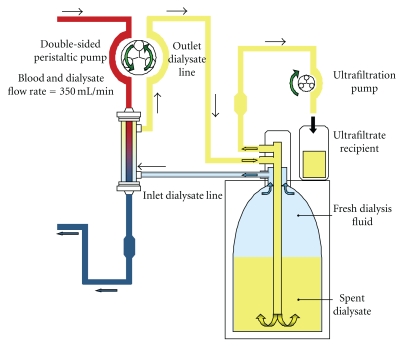

Total spent dialysate and ultrafiltrate can be collected in a calibrated tank. Partial dialysate collection can be performed via a time-driven sampling pump in the waste tubing. This system regularly collects a constant volume of fluid consisting of spent dialysate and ultrafiltrate [14]. Very recently, the GENIUS single-pass batch dialysis system (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany) was utilized in studies on CaMBs [9, 11, 12]. It was chosen because it offers the opportunity of effecting mass balances of any solute in a very precise way, at variance with those obtained with the standard single-pass dialysis systems, which are always at risk of systematic errors [15]. The characteristics of the GENIUS dialysis system are shown in Figure 1 and have been described elsewhere [16].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the GENIUS single-pass batch dialysis system.

Very few studies have been published which measured CaMBs in bicarbonate HD [5–13]. This is mainly due to the technical difficulties in achieving an accurate measurement of CaMBs owing to the need for the collection of the total spent dialysate or of a proportional aliquot of it [14].

Table 1 summarizes CaMBs obtained in the most relevant studies in bicarbonate HD [5–13]. Whereas no doubt exists about the fact that an inlet dialysate Ca concentration (CaD) of 1.75 mmol/L leads to a positive CaMB [5–9], more controversial is this issue, when dealing with a CaD of 1.50 mmol/L [5, 8–12] and, even more, when dealing with a CaD of 1.25 mmol/L [6–11, 13]. Worth noting, very recently Basile et al. showed that a CaD of 1.375 mmol/L was able to keep the patient in a mild positive tCaMB to maintain normal plasma Ca levels and not to stimulate PTH secretion [11].

Table 1.

Ca mass balances in bicarbonate HD with different inlet dialysate Ca concentration (CaD).

| Authors | Hours | Number of patients | CaD (mmol/L) | Calcium mass balance (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malberti et al. [5] | 4 | 20 | 1.75 | +80 ± 164 |

| Hou et al. [6] | 4 | 7 | 1.75 | +876 ± 92 |

| Fabrizi et al. [7] | 3 | 6 | 1.75 | +308 ± 52 |

| Al-Heijaili et al. [8] | 4 | 13 | 1.75 | +584 ± 196 |

| Karohl et al. [9] | 4 | 23 | 1.75 | +405 ± 413 |

| Malberti et al. [5] | 4 | 20 | 1.50 | −112 ± 80 |

| Malberti et al. [10] | 4 | 11 | 1.50 | −204 ± 124 |

| Al-Heijaili et al. [8] | 4 | 13 | 1.50 | −80 ± 64 |

| Karohl et al. [9] | 4 | 23 | 1.50 | +46 ± 400 |

| Basile et al. [11] | 4 | 22 | 1.50 | +293 ± 228 |

| Basile et al. [12] | 4 | 11 | 1.50 | +285 ± 137 |

| Basile et al. [12] | 8 | 11 | 1.50 | +298 ± 132 |

| Al-Heijaili et al. [8] | 8 | 13 | 1.50 | −171 ± 287 |

| Basile et al. [11] | 4 | 22 | 1.375 | +182 ± 125 |

| Basile et al. [11] | 4 | 22 | 1.25 | +75 ± 122 |

| Hou et al. [6] | 4 | 7 | 1.25 | +216 ± 136 |

| Fabrizi et al. [7] | 3 | 6 | 1.25 | −6 ± 36 |

| Malberti and Ravani [10] | 4 | 11 | 1.25 | −324 ± 156 |

| Al-Heijaili et al. [8] | 4 | 13 | 1.25 | −328 ± 108 |

| Karohl et al. [9] | 4 | 23 | 1.25 | −468 ± 563 |

| Sigrist and McIntyre [13] | 4 | 52 | 1.25 | −188 ± 232 |

| Karohl et al. [9] | 4 | 23 | 1.00 | −578 ± 389 |

Means ± SD. Solute removal during dialysis is expressed as a negative number, whereas solute gain is expressed as a positive number.

Another important issue is the appropriate CaD in long-hour slow-flow nocturnal HD. This issue has been addressed in very few studies [8, 12]. Al-Hejaili et al. showed that in order to remain in positive CaMB in long-hour slow-flow HD a patient requires the CaD to be in excess of 1.50 mmol/L [8]. By contrast, Basile et al. showed that, when using a CaD of 1.50 mmol/L, both treatments (4 h and 8 h) always achieved a positive iCaMB for the patients [12].

Finally, which CaMB should we study: iCaMB or tCaMB? A very recent study by Basile et al. [11] confirmed and extended data already published by Argiles et al. [14]: mean tCaMBs were less positive than mean iCaMBs for each of the CaD studied (1.25, 1.375 and 1.50 mmol/L), even though their difference did not reach the level of statistical significance [11]. When pooling all the 66 experiments (22 patients undergoing one experimental bicarbonate HD session with the three CaD), a mean difference of 9.8 percent between tCaMBs and iCaMBs was obtained [11]. This difference was less striking (4.7 percent), but statistically significant (P < .006), when comparing the ratios iCa/tCa of the fresh and spent dialysate obtained in the kinetic studies [11]. The figure of 4.7 percent was close to the values obtained by Argiles et al. [14]: the mean percent differences in their study were 8.3 and 5.0 between the ratios iCa/tCa of the fresh and spent dialysate, when using, respectively, a CaD of 1.25 and 1.50 mmol/L [14]. Furthermore, Argiles et al. claimed that phosphate captured by the dialysate fluid during its passage through the dialyzer may be responsible for such a shift between Ca pools [14]. Even though this is true, complexing of iCa by phosphate is probably only part of the truth. Actually, other anions may complex iCa, such as lactate, citrate, bicarbonate, and sulphate [17]. Furthermore, kinetic studies by Basile et al. showed that the main factor leading to precipitation of Ca complexes is probably the large difference in pH existing between the inlet dialysate and the ultrafiltrate recipient (Figure 1) [11]. In fact, Moore observed a decrease in iCa of ultrafiltrates above pH 7.3–7.6; this most likely represents a solubility (kinetic) problem related to variable precipitation of certain Ca complexes [17].

References

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) Kidney International. Supplement. 2009;113:S1–S130. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nouri P, Nikakhtar B, Llach F. Differential diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy. In: Nissenson AN, Fine RN, editors. Handbook of Dialysis Therapy. 4th edition. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: WB Saunders; 2008. pp. 965–986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosticardo GM. The diffusion gradient between ionized calcium in dialysate and plasma water-corrected for Gibbs-Donnan factor is the main driving force of net calcium balance during haemodialysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25(10):3458–3459. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotch F, Levin NW, Kotanko P. Calcium balance in dialysis is best managed by adjusting dialysate calcium guided by kinetic modeling of the interrelationship between calcium intake, dose of vitamin D analogues and the dialysate calcium concentration. Blood Purification. 2010;29(2):163–176. doi: 10.1159/000245924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malberti F, Surian M, Minetti L. Dialysate calcium concentration decrease exacerbates secondary hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients given calcium carbonate as a phosphate binder. Journal of Nephrology. 1991;4(2):75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou SH, Zhao J, Ellman CF, et al. Calcium and phosphorus fluxes during hemodialysis with low calcium dialysate. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1991;18(2):217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabrizi F, Bacchini G, Di Filippo S, Pontoriero G, Locatelli F. Intradialytic calcium balances with different calcium dialysate levels: Effects on cardiovascular stability and parathyroid function. Nephron. 1996;72(4):530–535. doi: 10.1159/000188934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Hejaili F, Kortas C, Leitch R, et al. Nocturnal but not short hours quotidian hemodialysis requires an elevated dialysate calcium concentration. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2003;14(9):2322–2328. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000083044.42480.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karohl C, De Paiva Paschoal J, De Castro MCM, et al. Effects of bone remodelling on calcium mass transfer during haemodialysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25(4):1244–1251. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malberti F, Ravani P. The choice of the dialysate calcium concentration in the management of patients of haemodialysis and haemodiafiltration. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2003;18(supplement 7):37–40. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basile C, Libutti P, Di Turo AL, et al. Comparison among different dialysate calcium concentrations in bicarbonate hemodialysis. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basile C, Libutti P, Di Turo AL, et al. Calcium mass balances during standard bicarbonate hemodialysis and long-hour slow-flow bicarbonate hemodialysis. Journal of Nephrology. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.6385. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sigrist M, McIntyre CW. Calcium exposure and removal in chronic hemodialysis patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2006;16(1):41–46. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argiles A, Mion CM, Thomas M. Calcium balance and intact PTH variations during haemodiafiltration. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 1995;10(11):2083–2089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basile C, Libutti P, Di Turo AL, et al. Haemodynamic stability in standard bicarbonate haemodialysis and long-hour slow-flow bicarbonate haemodialysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(1):252–258. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eloot S, Van Biesen W, Dhondt A, et al. Impact of hemodialysis duration on the removal of uremic retention solutes. Kidney International. 2008;73(6):765–770. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore EW. Ionized calcium in normal serum, ultrafiltrates, and whole blood determined by ion-exchange electrodes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1970;49(2):318–334. doi: 10.1172/JCI106241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]