Abstract

Background

Ewing sarcoma (ES) is the second most common bone tumor in children, and survival of those with metastatic ES has not improved. Previous studies have shown a survival benefit to whole lung irradiation in patients with pulmonary metastases and may be given either before, after, or instead of surgical pulmonary metastasectomy (PM). The contribution of surgery compared with irradiation in ES has not previously been studied.

Methods

A retrospective review of patients younger than 21 years (median age, 16 years) treated at a single institution (1990–2006) was performed. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using log-rank test and a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. P ≤ .05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Eighty patients with ES were identified. Of these, 31 (39%) had pulmonary metastases. Nine patients had incomplete details of their full treatment regimen, but the following groups could be defined from the remainder: resection alone (n = 5), radiation alone (n = 3), radiation and resection (n = 3), or chemotherapy alone (n = 11). There were 24 deaths overall, with a median overall survival (OS) of 2.7 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–5.2) years. Patients who had PM had the best OS (80%), whereas those who underwent radiation to the lung without PM compared with chemotherapy only for pulmonary metastasis both had similar OS of 0% at 5 years (P = .002). Patients who had radiation followed by PM for lung metastasis had a 5-year OS of 65%. Patients with PM had a longer OS compared with those without lung resection (P < .0001).

Conclusion

These data suggest a possible benefit for ES patients who undergo surgical resection of lung metastases.

Keywords: Metastasis, Pulmonary, Ewing sarcoma, Surgery, Metastasectomy

1. Background

Multidisciplinary treatment for pediatric Ewing sarcoma (ES) has resulted in improved outcome in patients with localized disease. These patients have estimated 5-year survival rates of about 70% [1–3]. However, for patients with metastatic disease, survival has not improved over the past 2 decades, with survival at about 25% [1,2]. Previous studies have shown that resection of pulmonary metastases of sarcoma, particularly osteosarcoma, has improved survival [4]. Because radiation to the lung has also shown improvement in survival in metastatic ES, standard Ewing protocols include radiation in addition to surgery [5]. There have been no studies to date that compare outcomes of surgery vs radiation therapy in the treatment of pulmonary metastases in ES.

At the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, patients with pulmonary metastases of ES have preferentially undergone whole lung radiation as the primary modality of treatment for their pulmonary disease as prescribed by the protocols of the Children’s Oncology Group. However, we have maintained an aggressive surgical approach to pulmonary metastases in this patient population, in both patients who have and have not undergone radiotherapy. Our study aims to show the impact of resection of pulmonary metastasis, compared with radiation therapy, on patient OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS) in pediatric ES patients.

2. Patients and methods

This study is a retrospective review of all ES patients identified treated at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between the years of 1990 and 2006 who were 21 years or younger at the time of initial diagnosis. All patients with primary bony Ewing sarcoma was included. A subset of these patients identified with lung metastasis as their first or only site of lung metastasis were studied. Demographic data including age, sex, and race were collected. Other variables examined included site of primary tumor (pelvic vs nonpelvic), the location of first identified metastases, and type of treatment—surgery and/or radiation. All patients received neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, but this was not uniform for the patients studied.

Log-rank test and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model were applied, and Kaplan-Meier curves were generated. Primary outcomes for demographic data were OS and RFS. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to death or last follow-up, whichever came first. Data are quoted as median (95% confidence interval [CI]). P ≤.05 was regarded as significant.

3. Results

A total of 80 children with ES were identified, and of these, 31 (39%) patients had pulmonary metastases. Nine patients had incomplete details of their full treatment regimen; but the following groups could be defined from the remainder: resection alone (n = 5), radiation alone (n = 3), radiation and resection (n = 3), or chemotherapy alone (n = 11). Overall, there were 24 deaths, with a median OS of 2.7 (95% CI, 1.7–5.2) years.

Univariate analysis showed no association of median OS with male sex (3.5 [95% CI, 3.3-NA) vs 1.7 [ 1.3–4.5] years; P = 0.2) or race (white; 2.7 [1.8–5.6] vs NA 2.5 [1.6-NA] years; P = 0.6). There was no significant difference in survival in patients when stratified by age (eg, <10 years vs >10 years (2 [1.7-NA] vs 3.3 [1.7–5.6] years; P = .94).

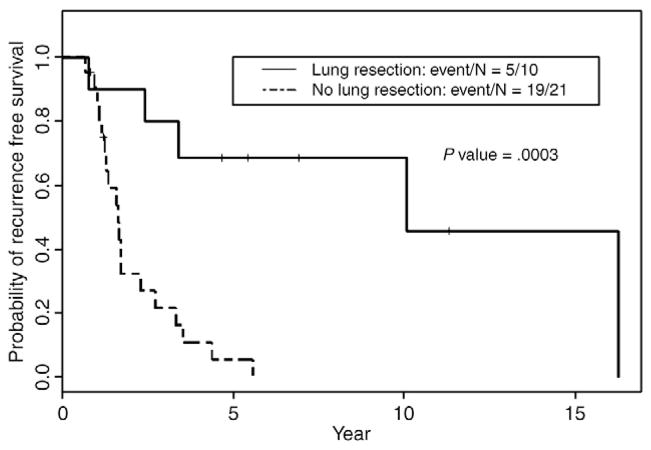

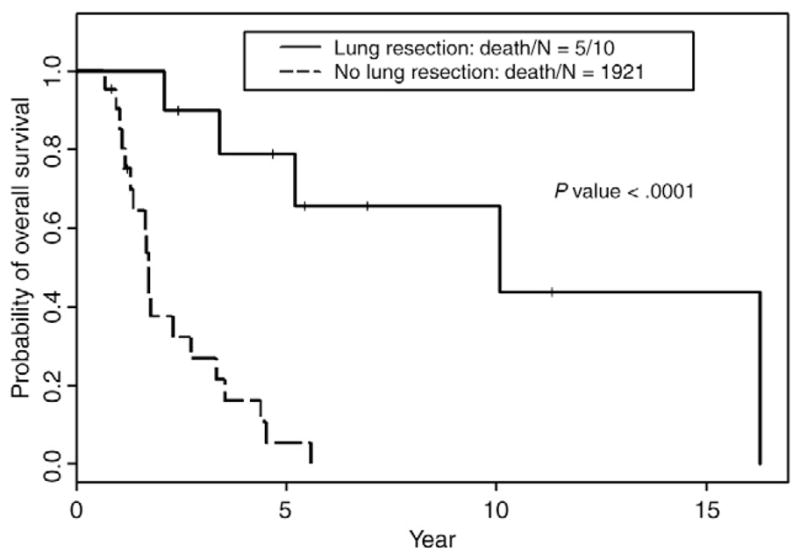

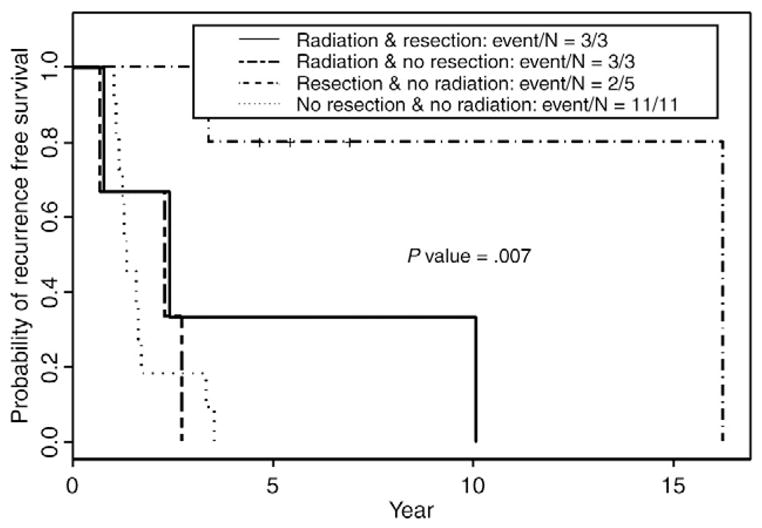

Patients with ES who underwent surgical resection of all lung metastasis (n = 10) had improved OS and DFS compared with those without lung resection (n = 21) (P < .0001 and P = .003, Figs. 1 and 2). There was no statistical difference in OS between those who underwent radiation and those who did not (Table 1). Using multivariate Cox analysis, lung resection was associated with improved OS. Previous studies have shown that lung only and lung plus other metastasis in ES do not have statistically different survival [6], and therefore, all were included. Furthermore, patients who had not undergone resection of their pulmonary nodules but had received chemotherapy and radiotherapy only were subject to a greater risk of death (hazard ratio, 15.1 [95% CI, 2.6–86.8]; P = .002). Patients with ES who underwent pulmonary resection but no radiation had the longest OS and DFS, when compared with radiation-alone patients who had the worse prognosis (Figs. 3 and 4). Patients with ES who underwent a combination of radiation and surgery fell in between (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of OS comparing ES patients who underwent surgical metastasectomy (n = 10) and those who did not (n = 21).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of RFS comparing ES patients who underwent surgical metastasectomy (n = 10) and those who did not (n = 21).

Table 1.

Hazard ratio (HR) comparing age, surgical resection of lung metastasis, and radiation

| HR (95% CI) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | >10 vs <10 | 0.34 (0.05–2.29) | .27 |

| Lung resected | No vs yes | 15.11 (2.63–86.78) | .002 |

| Lung radiation | No vs yes | 1.35 (0.46–3.96) | .59 |

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of OS comparing ES patients in 4 different groups: “radiation and resection” (n = 3), “radiation no resection” (n = 3), “resection no radiation” (n = 5), and “no resection no radiation” (n = 11).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve of RFS comparing ES patients in 4 different groups: “radiation and resection” (n = 3), “radiation no resection” (n = 3), “resection no radiation” (n = 5), and “no resection no radiation” (n = 11).

4. Discussion

Currently, there is no standardized treatment for resection of pulmonary metastases among children with ES, and no prospective randomized trials comparing radiation to surgical therapy of lung metastasis has been reported. Our study is the first to attempt to address the question of which regional therapy provides the best outcome for ES patients with lung metastasis. A small series that combined multiple tumor histologies and examined outcomes for resected pulmonary metastases in children showed either improved or comparable outcomes to radiation, surgery, or other alternative therapies [7]. A further study in 24 patients with ES and pulmonary metastases found that those who had metastasectomy had a statistically better OS, although there were no patients who had received lung radiation [8].

Here we show that surgical resection of lung metastasis may be superior to a combination of radiation and surgery or radiation alone. However, this study may be flawed by a selection bias in the patients who had surgically resectable disease, because most of those who presented with pulmonary metastasis were treated with bilateral total lung irradiation as mandated per protocol. Patients treated “off-protocol” at our institution underwent aggressive surgical resection when lung function would not be compromised as a result of the surgery before, after, or without lung radiation. Surgical resection was done primarily by wedge resection, removing all visible and palpable lesions. In some patients, more than 10 lesions were resected in 1 hemithorax.

Although the cohort size in this study is small, it is the largest single-institution study of lung metastasis in ES. We are a tertiary referral center, and this may be a potential source of bias because patients have already been previously treated or have been resistant to front-line chemotherapy.

The data presented here show that surgery for pulmonary metastases in ES is warranted and should be strongly considered. This study should provide a platform for clinical trials of ES patients with pulmonary metastasis comparing radiation therapy to surgery.

References

- 1.Ludwig JA. Ewing sarcoma: historical perspectives, current state-of-the-art, and opportunities for targeted therapy in the future. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:412–8. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328303ba1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotterill SJ, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, et al. Prognostic factors in Ewing’s tumor of bone: analysis of 975 patients from the European intergroup cooperative Ewing’s sarcoma study group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3108–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subbiah V, Anderson P, Lazar AJ, et al. Ewing’s sarcoma: standard and experimental options. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2009;10:126–40. doi: 10.1007/s11864-009-0104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harting MT, Blakely ML, Jaffe N, et al. Long term survival after aggressive resection of pulmonary metastases among children and adolescents with osteosarcoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:194–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briccoli A, Rocca M, Ferrari S, et al. Surgery for lung metastases in Ewing’s sarcoma of bone. Eur J Cancer Surg. 2004;30:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miser J, Goldsby R, Chen Z, et al. Treatment of metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: evaluation of increasing the dose intensity of chemotherapy—a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:894–900. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tronc F, Conter C, Marec-Berard P, et al. Prognostic factors and long-term results of pulmonary metastasectomy for pediatric histologies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:1240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karnak I, Emin Senocak M, Kutluk T, et al. Pulmonary metastases in children: an analysis of surgical spectrum. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:151–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]