Abstract

Purpose

To develop a non-contrast MR angiography (MRA) method for comprehensive evaluation of abdominopelvic arteries in a single 3D acquisition.

Materials and Methods

A non-contrast MRA (NC MRA) pulse sequence was developed using 4 inversion-recovery (IR) pulses and 3D balanced steady-state free precession (b-SSFP) readout to provide arterial imaging from renal to external iliac arteries. Respiratory triggered, high spatial resolution (1.3 × 1.3 × 1.7 mm3) non-contrast angiograms were obtained in seven volunteers and ten patients referred for gadolinium-enhanced MRA (CE MRA). Images were assessed for diagnostic quality by two radiologists. Quantitative measurements of arterial signal contrast were also performed.

Results

NC MRA imaging was successfully completed in all subjects in 7.0 ± 2.3 minutes. In controls, image quality of NC MRA averaged 2.79 ± 0.39 on a scale of 0 to 3, where 3 is maximum. Image quality of NC MRA (2.65 ± 0.41) was comparable to that of CE MRA (2.9 ± 0.32) in all patients. Contrast ratio measurements in patients demonstrated that NC MRA provides arterial contrast comparable to source CE MRA images with adequate venous and excellent background tissue suppression.

Conclusion

The proposed non-contrast MRA pulse sequence provides high quality visualization of abdominopelvic arteries within clinically feasible scan times.

Keywords: non-contrast MRA, abdominal MRA, bSSFP

Introduction

Non-invasive assessment of aortoiliac and renal arteries is crucial for diagnosis of renal artery stenosis, and inflow peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Contrast-enhanced MR angiography (CE MRA) is a primary non-invasive tool for evaluation of vascular pathology in the abdomen and pelvis (1, 2). However, recent safety concerns associated with gadolinium-based contrast agents (3) have spurred a renewed interest in non-contrast MRA (NC MRA) techniques (4).

Pre-conditioning radio-frequency (RF) pulses for background tissue suppression and inflow of unsaturated arterial blood for high vascular signal have been previously used in non-contrast angiographic techniques (5, 6). Inflow-based NC MRA with 3D balanced steady-state free precession (b-SSFP) readout and a slice-selective (SS) inversion recovery (IR) pulse has been developed for evaluation of renal arteries (7) and validated in patients with renal artery stenosis (8–11) and renal transplants (12). IR b-SSFP MRA is typically performed axially with 100 – 120 mm craniocaudal coverage, with a single SS-IR pulse applied transversely to completely overlay the imaging slab and to extend inferiorly for venous suppression. The superior-inferior distance from renal arteries to distal external iliac arteries is on the order of 300 mm. Thus, conventional IR b-SSFP MRA is inadequate for comprehensive assessment of abdominal and pelvic arteries. One approach to extend the coverage is to perform coronal imaging (13), allowing for extended visualization of the aorta. However, it is challenging to find an inversion time that is sufficient to allow unsaturated arterial blood to reach the distal iliac arteries without substantially compromising background suppression. To our knowledge an NC MRA technique that can provide craniocaudal coverage from renal to distal iliac arteries with adequate background suppression in a single acquisition has not been reported.

In this study, the craniocaudal spatial coverage of IR b-SSFP MRA was extended by utilizing four IR pre-conditioning pulses. The objectives of this work were to develop an NC MRA pulse sequence for extended coverage of the abdominopelvic arteries and to evaluate its performance in healthy controls and patients.

Materials and Methods

Quadruple IR Pulse Sequence

The quadruple IR pulse scheme was designed to achieve: i) craniocaudal coverage of the abdominopelvic arteries from suprarenal aorta to distal iliac arteries and ii) adequate background suppression. Figure 1a illustrates the pulse sequence. First, a non-selective (NS) IR pulse is applied with inversion time TI to invert the longitudinal magnetization (Mz) of all tissues. Immediately after the NS-IR pulse, an oblique sagittal slice-selective (SS) IR pulse overlying the aorta is applied to re-invert aortic spins between the top of the FOV and the aortic bifurcation to equilibrium magnetization (M0). By "pre-filling" fully-magnetized arterial spins up to the aortic bifurcation, the time needed for fresh arterial spins to arrive at the distal iliac arteries is reduced. Arterial coverage beyond the aortic bifurcation is governed by TI and the flow rate of arterial blood.

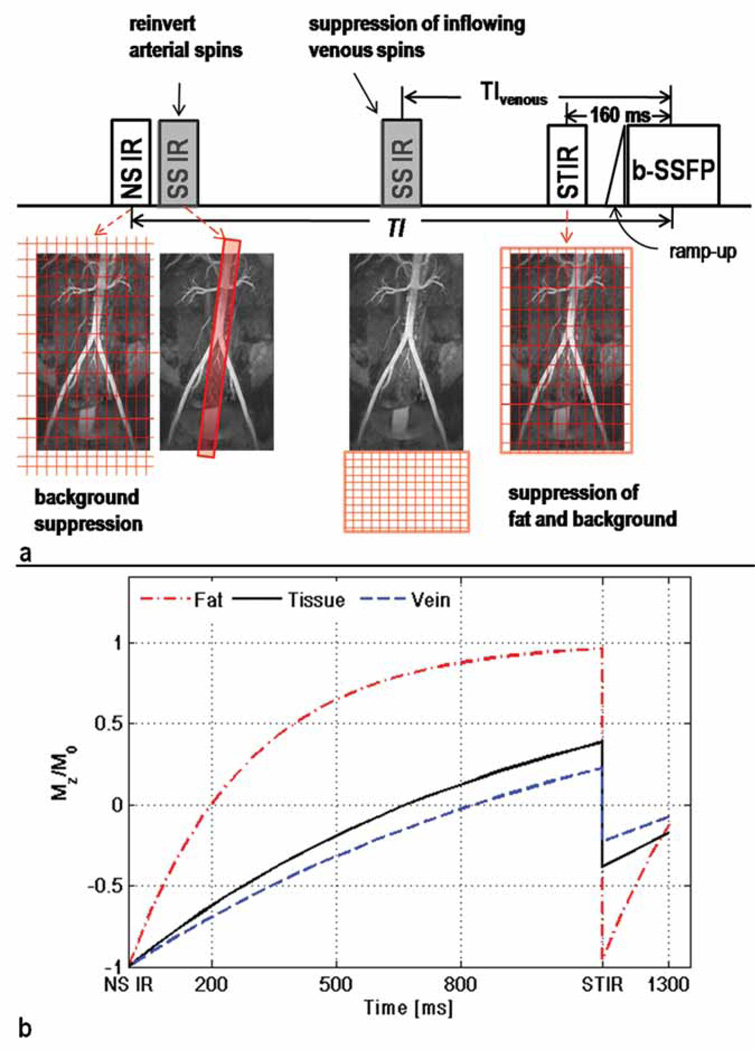

Figure 1.

a) Pulse sequence diagram of NC MRA with quadruple IR preparation. An NS-IR pulse is applied with inversion time TI for background suppression. Subsequently, the aorta is reinverted by an SS-IR pulse, prescribed sagittally. A third SS-IR pulse with inversion time TIvenous is applied inferiorly to the imaging FOV for suppression of inflowing venous blood. A STIR pulse is applied with inversion time of 160 ms for fat suppression and additional attenuation of background tissues. The b-SSFP readout is preceded by 10 linearly increasing excitation pulses (ramp-up) to accelerate the approach to steady-state. The 3D b-SSFP imaging is performed with 90° excitation pulses and linear k-space ordering to further attenuate background tissues which have relatively low T2. The center of k-space is acquired a time interval TI after to the first inversion.

b) Plots of Mz/M0 as function of time after IR pulses for three types of background tissues: veins, tissue, and fat. Mz was calculated for background tissues outside the sagittally oriented IR slab, which do not experience the first SS IR (in gray) and are not excited by the second SS-IR (in gray). The choice of TI (1300 ms) guarantees near complete suppression of background signals at the center of k-space. Background spins within the sagittal SS-IR slab will appear as a ‘band’ of brighter signal compared to the rest of the background.

Subsequent to the NS-IR, Mz of background (e.g., fat, muscle, veins) outside of the sagittal SS-IR excitation slab undergoes magnetization recovery until a short tau IR (STIR) pulse with TI 160 ms is applied to suppress fat and further attenuate background signals. A second SS-IR pulse, positioned axially and caudal to the FOV, is applied prior to the STIR pulse with inversion time TIvenous for suppression of inflowing spins from femoral veins. Imaging is performed with oblique coronal 3D b-SSFP readout with 90° excitation RF pulses and linear k-space ordering to further attenuate background signals. Note that background spins within the sagittal SS-IR excitation slab are fully magnetized prior to the STIR pulse; their signal will be attenuated by the STIR and b-SSFP readout.

Selection of IR Pulse Timing Parameters

In this subsection, we describe preliminary in vivo and numerical experiments used to design the pulse sequence for NC MRA studies.

TI for Background Suppression and Arterial Coverage

Both arterial coverage and magnitude of background Mz are a function of TI: longer TI extends coverage at the cost of increased background signal and vice versa. We performed in vivo velocity measurements to estimate TI necessary for sufficient coverage and numerical simulations to calculate TI for adequate background suppression.

To identify TI for sufficient arterial inflow, mean arterial velocity over one cardiac cycle was measured at the origin of the iliac arteries in 14 patients (7 female, 7 male; age range 29–93, mean age 65) undergoing chest or peripheral MRA. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was waived. Measurements were performed with electrocardiogram (ECG) gated phase contrast MRI (2D FLASH, TR 65.3 ms, TE 5.07 ms, FA 20°, TA 18–24 sec, through-plane velocity encoding 100–120 cm/s). Flow velocities were measured using Siemens Argus software with regions of interest drawn to encompass the entire vessel lumen, excluding the vessel wall. Individual patient measurements were averaged to calculate mean arterial velocity, Vavg, across all subjects. To obtain arterial visibility from the renal to the distal iliac arteries, the entire length of the iliac arteries which measure on the order of 200 mm has to be filled with unsaturated arterial blood. Assuming constant arterial velocity, a rough estimate of TI for sufficient coverage was calculated by TI = 200mm/Vavg.

In the preliminary study of 14 patients (5 without pathology, 1 with dissecting descending aorta, 3 with infrarenal aneurysm, 3 with enlarged thoracic aorta, 2 with iliac stenosis) presence and severity of disease varied considerably, resulting in a wide range of measured velocities, varying from 4.7 to 23.2 cm/s, with Vavg = 13.8 ± 4.8 cm/s. To calculate TI appropriate for volunteers without pathology, two patients whose measurements were obtained within abdominal aortic aneurysms were excluded from analysis, resulting in Vavg = 15.2 ± 3.1 cm/s and TI for suitable coverage of approximately 1300 ms. For subsequent in vivo NC MRA imaging, TI was set to 1300 ms when no disease was suspected and was prolonged by 400 ms when indications for reduced flow rates were present.

To examine whether the TI values identified for sufficient coverage should theoretically provide adequate background suppression, Mz at the center of k-space was calculated using the Bloch equation governing T1 relaxation for three types of background (veins, tissue, and fat). Plots (Fig. 1b) of Mz as a function of time after IR pulses demonstrate near complete suppression of background signals at the center of k-space with TI = 1300 ms. When TI is prolonged to 1700 ms (plot not shown), background Mz increases compared to the 1300 ms case as follows: venous Mz from 0.07M0 to 0.27M0, tissue Mz from 0.17M0 to 0.35M0, and fat Mz from 0.13M0 to 0.14M0. These values imply that background signal will be brighter with TI = 1700 ms, but will remain sufficiently low for satisfactory arterial conspicuity. All results were calculated assuming complete inversion of magnetization by IR pulses, ideal slice profile of SS-IR, and tissue T1 966 ms (14), fat T1 288 ms (15), and venous T1 1200 ms (16).

TIvenous for Suppression of Inflowing Venous Blood

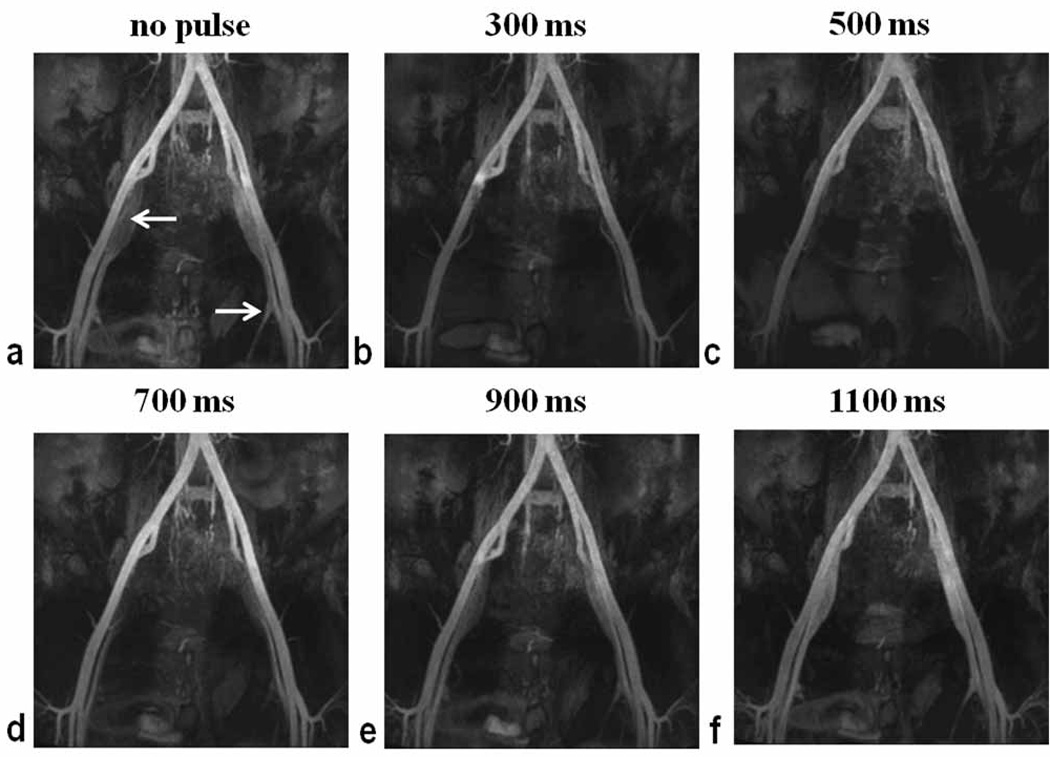

Given the unknown efficacy of the IR pulses outside the FOV, a range of TIvenous values were tested in two volunteers (2 male, ages 30 and 49) to empirically determine TIvenous for optimal suppression of inflowing venous blood from femoral veins. NC MRA was performed with the following settings for TIvenous of the caudal SS-IR pulse: none, 300 ms, 500 ms, 700 ms, 900 ms, and 1100 ms. Signal intensity of the iliac veins was assessed to determine TIvenous yielding minimal venous signal. TIvenous of 500 ms provided best suppression (Fig. 2) and was used for subsequent in vivo NC MRA imaging.

Figure 2.

Maximum intensity projection images of left and right iliac arteries and veins obtained with NC MRA in a male volunteer (age 30). Signal intensity of left and right common and external iliac veins was assessed for the following settings of the caudal SS-IR pulse: none (a), TIvenous 300 ms (b), TIvenous 500 ms (c), TIvenous 700 ms (d), TIvenous 900 ms (e), and TIvenous 1100 ms (f). Best suppression of inflowing venous blood was obtained with TIvenous = 500 ms. Arrows denote the location of external iliac veins.

Human Subject Scanning

Following the determination of our imaging protocol, seven healthy volunteers (1 female, 6 male, age range 23 – 52 yrs; mean age 34 yrs) and 10 patients (4 female, 6 male; age range 57 – 85 yrs; mean age 73 yrs) were studied with the proposed NC MRA technique. Patients were referred for clinical CE MRA for suspected claudication (n=7) or aortic aneurysm (n=3). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Imaging was performed on a whole-body 1.5T system (Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany; maximum gradient strength = 45 mT/m; slew rate = 200 T/m/s). Radio-frequency excitation was performed using the body coil; two body coil arrays and a spine coil array were employed for signal reception.

NC MRA

A three-plane dark-blood Half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) scout scan was used for image planning. Subsequently, NC MRA was performed using an oblique coronal imaging slab, oriented along the abdominal aorta, with respiratory bellows for triggering (20% end expiration). Imaging parameters included: TR 1 respiratory cycle, TE 1.7 ms, FA 90°, BW 1042 Hz/pixel, 60 k-space lines per shot, 2 shots per partition, generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA)(17) effective acceleration factor 2.7, FOV 400 mm × 400 mm, 60–80 partitions, nominal slice thickness 1.7 mm, acquisition matrix = 320 × 307, slice resolution 65 %, phase oversampling 10 %, slice oversampling 20–40 %, spatial resolution 1.3 mm × 1.3 mm × 1.7 mm. IR parameters included: NS IR pulse with TI between 1300 ms and 1700 ms as detailed below; 20–60 mm thick IR pulse oriented in oblique sagittal plane overlying the abdominal aorta (inversion time 1280ms); 200 mm thick SS-IR pulse positioned axially immediately inferior to the FOV(TIvenous = 500 ms); STIR with inversion time 160 ms.

All volunteers underwent imaging using the aforementioned protocol. In addition, one of the control subjects (male, age 29) was imaged with the sagittal SS-IR pulse turned off to illustrate the utility of the re-inversion pulse. The effect of the position and thickness of this pulse was further investigated in a volunteer with known scoliosis (female, age 51). Imaging was performed with TI = 1300 ms for two positions of the sagittal slab and repeated with TI = 1500 ms to illustrate the influence of TI on arterial visibility and background suppression. Four patients were imaged with TI = 1300 ms; in six patients TI = 1700 ms was used in view of indications of reduced flow rates (e.g., age ≥ 70years, known aneurysm).

CE MRA

Bolus-chase gadolinium-enhanced MRA was acquired after injection of 30 mL of dilute contrast (22.5 mL Gd-DTPA) initially at 2 mL/s for 20 mL of dilution, then at 1 mL/s for 10 mL of dilution and a 20-mL saline flush. Timing was based on time-to-peak enhancement of the distal infrarenal aorta and a standard formula (18). The 3D T1-weighted FLASH sequence was performed with the following parameters: TR/TE 2.9/0.9 ms, FA 25°, nominal voxel size 1.4 mm × 1.3 mm × 1.4 mm, slice resolution 62%.

Image Quality Assessment

Qualitative Assessment

All data were de-identified and randomized for blinded review by two radiologists with 4 and 5 years MRA experience who independently scored the images. Source images were used for both NC MRA and CE MRA evaluation. Eight vascular segments per subject (suprarenal artery, right and left renal artery, infrarenal artery, right and left common iliac, right and left external iliac) were assessed for diagnostic quality on a 4-point scale (0 = non-diagnostic, 1 = partially evaluable, 2 = mostly evaluable, 3 = fully evaluable). Presence of artifacts was recorded on per segment basis. Each image received an overall diagnostic-quality score based on the same scale.

Quantitative Assessment

Prior to quantitative assessment, 5mm thick axial reconstructions of all 3D data sets were obtained on an independent workstation (Leonardo, Siemens Healthcare). Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was performed on 12 of the resultant slices, grouped in 4 sets of 3, representative of the following arterial segments: suprarenal, infrarenal, common iliac, and external iliac. Arterial (SA) and venous (SV) signal intensities were estimated as the mean intensity of all pixels contained within ROIs drawn to include the entire vessel lumen. Common and external iliac SA and SV were calculated by averaging the intensities of the left and the right branches. ROIs for background signal (SB) estimation were placed over the right lobe of the liver for suprarenal slices and over the iliopsoas muscle for all remaining segments.

Signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise ratio measurements were not performed due to the spatially inhomogeneous (i.e., g-factor) noise produced by GRAPPA reconstruction. Instead, relative signal contrast ratio between artery and background muscle, CRA-B (= (SA−SB)/SA), as well as between artery and vein, CRA-V (= (SA−SV)/SA), were estimated for source NC MRA images and for source and subtraction CE MRA images. To evaluate the efficacy of venous suppression, vein-to-background contrast, CRV-B (= (SV−SB)/SA), was also measured. Mean CRA-B, CRA-V, and CRV-B across all patients were calculated for the above-identified segments; individual segment measurements were averaged to obtain overall contrast ratios for the entire image.

Craniocaudal Arterial Coverage

Maximal visible length of the common and external iliac arteries obtained with NC MRA was measured as a fraction of total “Iliac” length. The latter was defined from aortic bifurcation to origin of profunda femoris. One radiologist reviewed the axial reconstruction images and recorded the last slice position in which the iliac segments were diagnostic. Visible length of the iliacs was measured between this slice position and the aortic bifurcation. Longitudinal views of the iliac segments, obtained by curved multi-planar reconstructions, were used for all measurements to control for differences in vessel geometry and orientation of the imaging slab.

Statistical Analysis

Diagnostic quality scores of NC MRA images obtained in patients were compared to the reference standard (CE MRA) with a Wilcoxon signed rank test. A paired Student’s t-test was performed to determine the statistical significance of differences in CA-B, CA-V, and CV-B between: a) source NC MRA and source CE MRA, and b) source NC MRA and subtraction CE MRA. In all tests, a P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Microsoft Office Excel version 12 was used for all analyses.

Results

Non-contrast angiograms were successfully obtained with quadruple IR b-SSFP in all subjects. NC MRA scan duration was respiratory-rate dependent and averaged 7.0 ± 2.3 minutes.

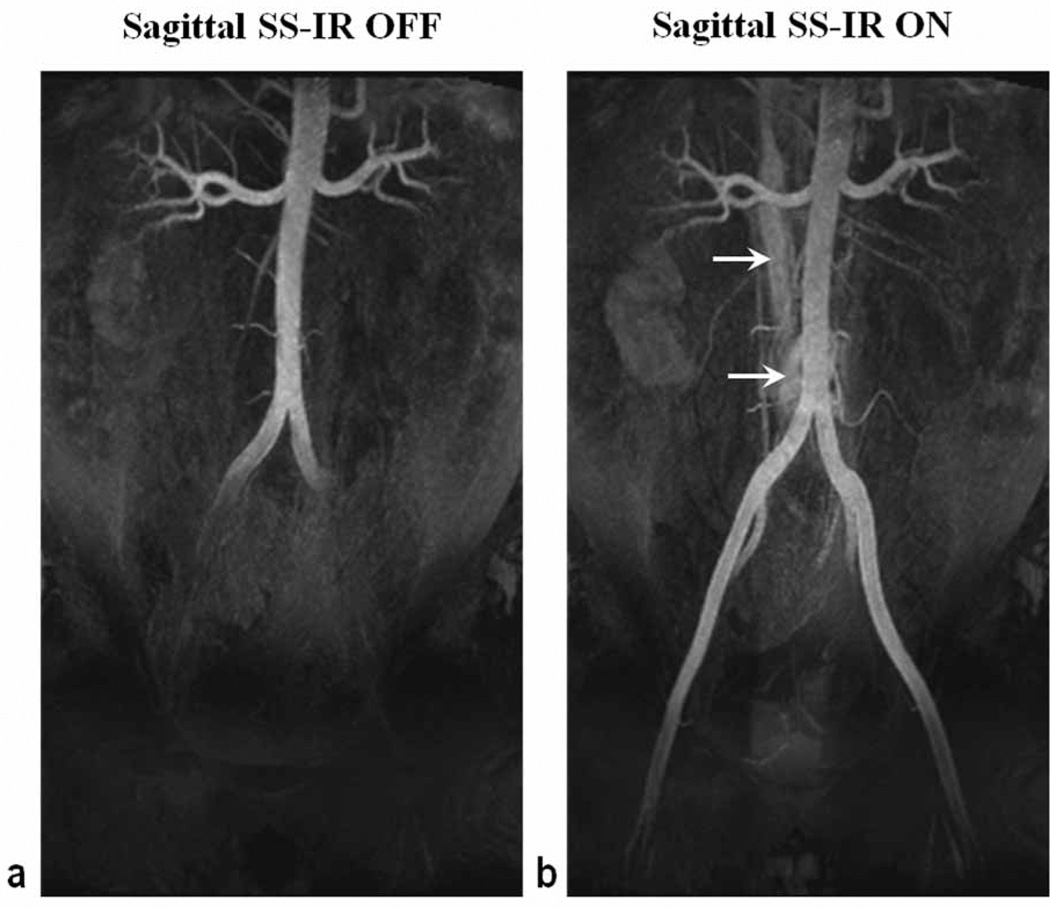

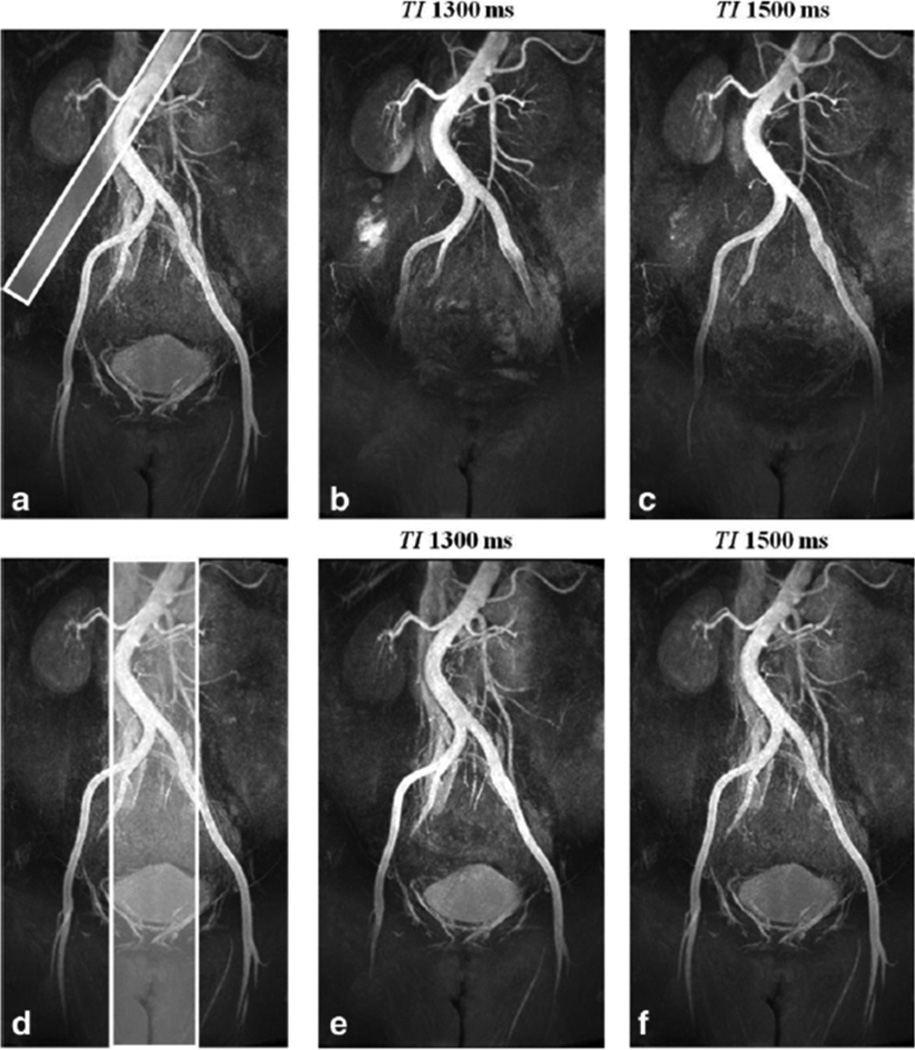

Effect of sagittal SS-IR Pulse on Craniocaudal Coverage and Image Contrast

Figure 3 shows representative NC MRA images acquired with and without the SS-IR pulse, with all other parameters the same. With TI set to 1300 ms in both cases, the application of the SS-IR pulse increased craniocaudal coverage by approximately 170 mm without prolonging inflow time at the expense of brighter background coincident with the location of the reinversion pulse. Figure 4 shows results obtained in the volunteer who presented with scoliosis. When the reinversion slab overlaid only half of the infrarenal aorta (Fig. 4a), arterial coverage was limited to the common iliac arteries with TI of 1300 ms (Fig. 4b). Coverage, measured distally to the aortic bifurcation, was extended from 140 mm to 185 mm when TI was prolonged to 1500 ms (Fig. 4c). It was also possible to extend arterial conspicuity without increasing TI by simply re-orienting and enlarging the SS reinverion pulse to overlay the entire infrarenal aorta (Fig. 4e). However, with a thicker SS-IR pulse, CRA-V decreased by approximately 20% due to reinversion of the vena cava. Reduced contrast between left renal artery and kidney cortex was also observed.

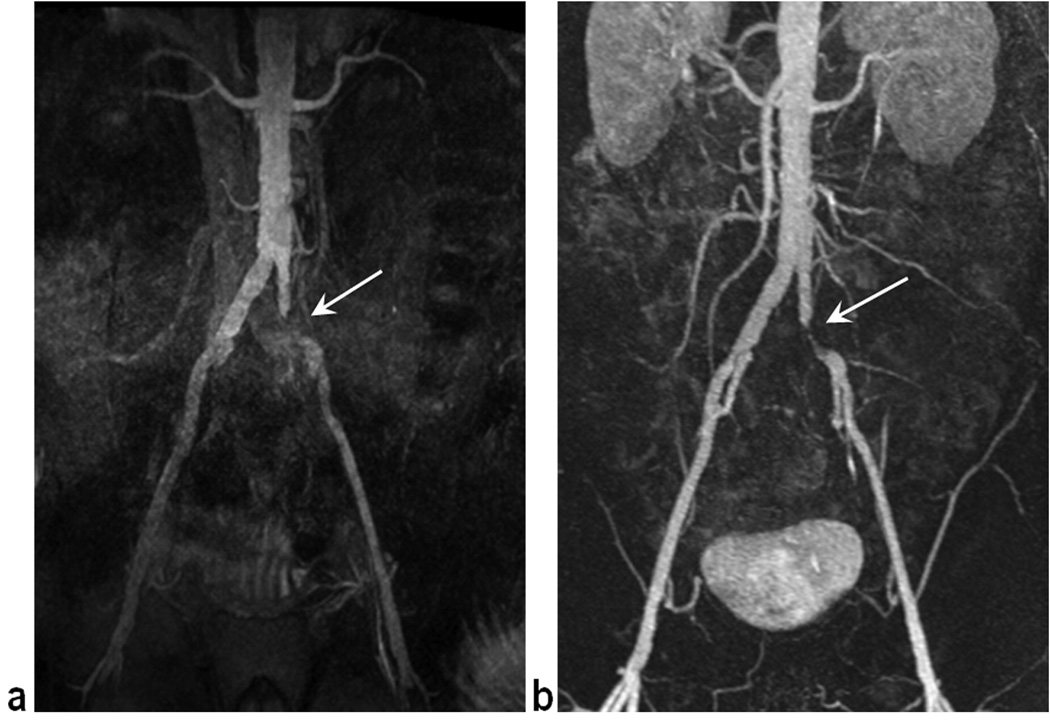

Figure 3.

Representative NC MRA images, obtained in a 29 year old male volunteer without (a) and with (b) the sagittal SS-IR pulse, demonstrate the utility of the re-inversion pulse to reduce the time needed to achieve complete filling of fully magnetized arterial spins from renal to distal iliac arteries. With all other parameters kept the same, the application of the SS-IR pulse increased craniocaudal coverage by approximately 170 mm without prolonging inflow time at the expense of brighter background (arrows) coincident with the location of the reinversion pulse. Both images were acquired with TI = 1300 ms.

Figure 4.

NC MRA obtained in a 51 year old female volunteer with scoliosis. When a 20-mm thick SS-IR pulse overlaid only half of the infrarenal aorta (a), arterial coverage was limited to the common iliac arteries with TI of 1300 ms (b). Coverage, distal to the bifurcation, increased from 140 to 185 mm with TI = 1500 ms (c). With a 75-mm thick SS-IR pulse (d), overlaying the entire infrarenal aorta, arterial conspicuity extended distally to the origin of the profunda femoris artery for both TI of 1300 ms (e) and 1500 ms (f). The thicker inversion resulted in reduced contrast between left renal artery and kidney cortex and a 20% decrease in artery-to-vein contrast (CRA-V) due to reinversion of the vena cava.

Image Quality

Volunteers

In the seven volunteers overall image quality (Table 1) averaged 2.79 ± 0.39 on a scale of 0 to 3, where 3 is maximum. Using individual reader evaluations a total of 112 segments were assessed, of which 86% (96/112) were rated fully evaluable (score = 3). Fifteen (13%) segments received a score of 2 (mostly evaluable), occurring in the external iliac arteries (n=4) and the suprarenal aorta (n=11). The latter exhibited reduced signal intensity likely caused by rapid flow of blood through an off-resonance region. One (1%) segment, part of an external iliac artery, was judged partially evaluable due to insufficient inflow of unsaturated blood.

Table 1.

Image quality ratings for NC MRA in 7 volunteers and NC MRA and CE MRA in 10 patients.

| Arterial Segment | NC MRA (volunteers) |

NC MRA (patients) |

CE MRA (patients) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall image quality | 2.79 ± 0.39 | 2.65 ± 0.41 | 2.90 ± 0.32 |

| Suprarenal artery | 2.50 ± 0.41 | 2.50 ± 0.39 | 2.90 ± 0.32 |

| Left renal artery | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 2.82 ± 0.40 | 2.90 ± 0.32 |

| Right renal artery | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 2.82 ± 0.40 | 2.90 ± 0.32 |

| Infrarenal artery | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 2.90 ± 0.32 |

| Left com iliac artery | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 2.77 ± 0.47 | 2.94 ± 0.17 |

| Right com iliac artery | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 3.00 ± 0.00 |

| Left ext iliac artery | 2.71 ± 0.57 | 2.59 ± 0.49* | 3.00 ± 0.00* |

| Right ext iliac artery | 2.78 ± 0.39 | 2.50 ± 0.55* | 3.00 ± 0.00* |

p < 0.05.

Artery-to-background contrast, CRA-B, obtained in volunteers (Table 2) averaged 0.90 ± 0.03 with little variation across segments. Net CRA-V and CRV-B were 0.67 ± 0.12 and 0.23 ± 0.10, respectively, signifying adequate venous suppression.

Table 2.

Contrast ratios for NC MRA in volunteers (n = 7) and NC MRA and CE MRA in patients (n = 10)

| Arterial Segment | NC MRA volunteers |

NC MRA patients |

CE MRA (source) |

CE MRA (subtraction) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRA-B | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | |

| Overall | CRA-V | 0.67 ± 0.12 | 0.55 ± 0.17 | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 0.95 ± 0.03 |

| CRV-B | 0.23 ± 0.10 | 0.29 ± 0.13 | 0.10 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | |

| CRA-B | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.13 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | |

| Suprarenal | CRA-V | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 0.51 ± 0.19 | 0.75 ± 0.17 | 0.94 ± 0.06 |

| CRV-B | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 0.27 ± 0.17 | 0.07 ± 0.07 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | |

| CRA-B | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | |

| Infrarenal a | CRA-V | 0.60 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 0.75 ± 0.15 | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| CRV-B | 0.30 ± 0.30 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.10 ± 0.11 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | |

| CRA-B | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.02 | |

| Common iliac a. | CRA-V | 0.65 ± 0.15 | 0.56 ± 0.20 | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.96 ± 0.03 |

| CRV-B | 0.26 ± 0.14 | 0.30 ± 0.15 | 0.10 ± 0.08 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | |

| CRA-B | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | |

| External iliac a. | CRA-V | 0.77 ± 0.10 | 0.58 ± 0.24 | 0.66 ± 0.17 | 0.96 ± 0.02 |

| CRV-B | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.20 | 0.14 ± 0.11 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | |

Patients

In the ten patients, 82% (131/160) of all reviewed segments were rated as fully evaluable, while 24 (15%) received a score of 2. Five segments (3%), encountered in the common (n=1) and external (n=4) iliac arteries, were scored as partially evaluable. None were non-diagnostic. Overall image quality score of NC MRA (2.65 ± 0.41) was comparable to that of CE MRA (2.9 ± 0.32) with no statistically significant difference observed between the two (P>0.2). When image quality scores of NC MRA and CE MRA were compared on per segment basis (Table 1), statistically significant differences were found only for the left and right external iliac arteries, with readers describing the following artifacts: insufficient inflow (n=1) and air-filled bowel peristalsis (n = 2).

Overall artery-to-background contrast, CRA-B, with NC MRA averaged 0.84 ± 0.06, 14% lower than CRA-B of subtraction CE MRA. However, CRA-B of the non-contrast technique was comparable to that of source CE MRA with no statistically significant difference observed between the two (Table 2). CRA-V of NC MRA averaged 0.55 ± 0.17 and was significantly lower than CRA-V of both source and subtraction CE MRA.

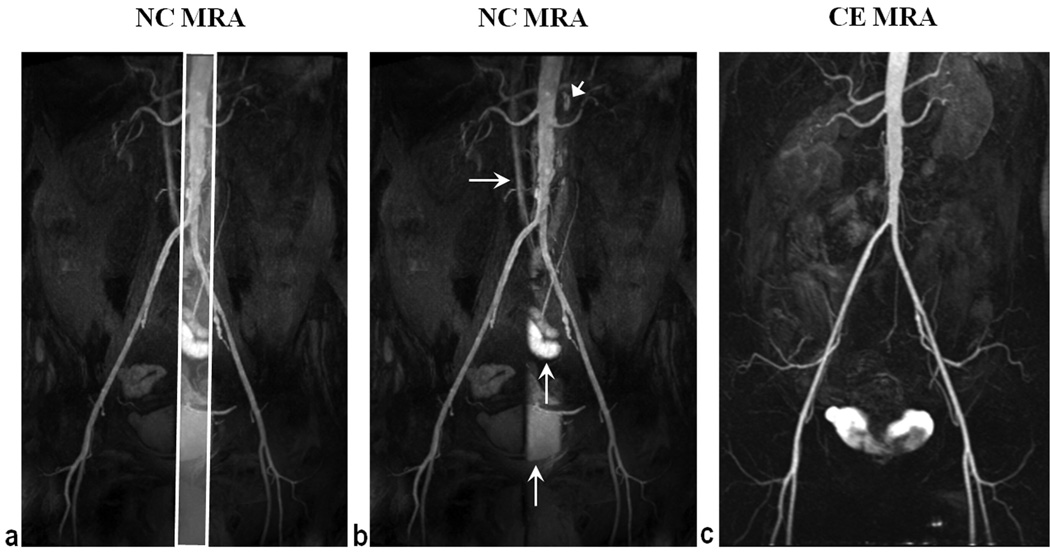

Fig. 5b shows a representative NC MRA image with the maximum image quality score obtained in a 66 year old patient. Overall artery-to-background signal contrast, CRA-B = 0.92, was comparable to subtraction (CRA-B = 0.98) and source (CRA-B = 0.86) CE MRA. Venous signal throughout the image was deemed low by both readers, signifying adequate venous suppression, confirmed by contrast ratio measurements (CRA-V = 0.78, CRV-B = 0.13). However, medium to high venous signal was observed in a portion of the vena cava due to the sagittal SS-IR pulse. Increased signal intensity, coincident with the location of the sagittal re-inversion pulse, was also encountered in lymph nodes, bladder, and bowel tissue.

Figure 5.

Sub-volume MIP of NC MRA (a, b) and full volume MIP of subtraction CE MRA (c) obtained in a 66 year old patient. CRA-B = 0.92 for NC MRA, comparable to subtraction CE MRA (CRA-B = 0.98) and higher than source CE MRA (CRA-B = 0.86). Increased background signal intensity, coincident with the location (a) of the reinversion pulse, was observed with NC MRA in the vena cava (horizontal arrows), lymph nodes (arrow head), bowel, and bladder (vertical arrows). Anterior-posterior coverage of NC MRA was smaller than that of CE MRA causing the truncated appearance of the internal iliac arteries. NC MRA depicted mild infrarenal aortic atherosclerosis and left internal iliac artery origin stenosis in agreement with CE MRA.

Craniocaudal Coverage

Craniocaudal coverage obtained with NC MRA is summarized in Table 3. In volunteers, visualized arterial length distal to the bifurcation averaged 209 – 218 mm. Similar inflow distances were observed in patients, corresponding to optimal visualization of 93–96% of the full length of the iliac arteries. In patients, similar coverage was observed for the different TI values used (1300 and 1700 ms) likely due to variation of disease severity and cardiac output between the two groups.

Table 3.

Mean craniocaudal coverage of arterial inflow obtained with NC MRA volunteers (n =7) and patients (n=10)*

| Subject Group |

Iliac length (right) |

Total visible distance (right) |

% visible iliac segment (right) |

Iliac length (left) |

Total visible distance (left) |

% visible iliac segment (left) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteers (TI: 1300ms) | 217 ± 8 | 218 ± 34 | 94 ± 8 % | 205 ± 16 | 209 ± 48 | 93 ± 10 % |

| Patients (TI: 1300ms) | 212 ± 19 | 202 ± 25 | 96 ± 5 % | 211 ± 18 | 207 ± 55 | 93 ± 9 % |

| Patients (TI: 1700ms) | 228 ± 38 | 217 ± 40 | 95 ± 4 % | 216 ± 31 | 206 ± 32 | 95 ± 4 % |

Distance is measured in millimeters distal to the aortic bifurcation

The left external iliac artery was successfully completely visualized distal to severe stenosis of the common iliac artery in a 66 year old patient imaged with TI = 1300ms (Fig. 6). In an 80 year old patient (Fig. 7), near complete (96%) depiction of bilateral iliac arteries was obtained distal to an aortic aneurysm by extending TI to 1700ms and broadening the SS-IR pulse to completely cover the aneurysm. Suboptimal inflow occurred in one volunteer (visible left iliac 75%, visible right iliac 77%) and one patient without pathology (visible left iliac 82%, visible right iliac 91%) both imaged with TI 1300ms.

Figure 6.

In a 66 year old male patient, imaged with TI = 1300 ms, NC MRA (a) demonstrated complete visualization of the left iliac segment, distal to sever common iliac stenosis (arrows), confirmed by CE MRA (b). Overall image quality of NC MRA was undermined due to anterior-posterior aliasing. Note that NC MRA resulted in overestimation of stenosis severity.

Figure 7.

In an 80 year old male patient, 96% of the length of the iliac arteries was visualized distal to aortic aneurysm with prolonged TI of 1700 ms. The thickness of the SS-IR pulse was extended to completely overlie the aneurysm at the expense of near complete reinversion of the vena cava and partial reinversion of the right external iliac vein (arrows). In this patient CE MRA yielded poor image quality due to mistiming of the contrast injection and is not shown.

Vascular pathology was present in five patients. Left and right renal artery stenosis, mild infrarenal atherosclerosis, and infrarenal aortic aneurysm were identified by NC MRA in agreement with CE MRA findings. In one subject, common iliac stenosis was overestimated by NC MRA, compared to the reference CE MRA image (Fig. 6).

Discussion

This study describes a new NC MRA pulse sequence for assessment of abdominopelvic arteries, using four IR preconditioning pulses and 3D b-SSFP readout with respiratory trigger. The proposed technique is an extension of the previously described IR b-SSFP MRA sequence for renal angiography. The novelty of the quadruple IR b-SSFP method compared to the renal technique lies in the fact that arterial visualization was extended without prolonging inflow time.

Results obtained in controls and patients demonstrate the feasibility to achieve arterial visibility from suprarenal aorta to distal external iliac arteries with sufficient background suppression. As evidenced by CRA-B measurements NC MRA exhibited good static background attenuation in both controls and patients, comparable to CRA-B of source CE MRA. These results reflect the efficacy of the IR preconditioning for background nulling. The STIR pulse was essential for robust suppression of subcutaneous fat and short-T1 intestinal contents. A STIR pulse was chosen instead of a chemical-shift selective RF pulse, which is more sensitive to static field (B0) and transmit RF field (B1) inhomogeneities, especially given a large FOV. The STIR pulse combined with the b-SSFP readout with large excitation angles and linear k-space ordering maintained adequate static tissue suppression even when TI was prolonged for extended coverage.

Venous suppression was achieved by two separate mechanisms. Signal from venous spins that remain within the FOV throughout the entire experiment (i.e., venous blood that originally occupies the iliac veins and moves to the vena cava by the start of the readout) is attenuated by the NS-IR and the STIR pulses. Signal from inflowing venous blood, found primarily in the external and common iliac veins, is governed by the inversion time of the caudal SS-IR pulse. Overall venous suppression was adequate with external iliac veins exhibiting more favorable CRA-V and CRV-B compared to other segments. This was due to the reinversion effect of the sagittal SS-IR that frequently affected the vena cava and a portion of the common iliac veins.

Respiratory motion in the abdomen and pelvis poses a challenge to the robustness of non-contrast MRA techniques. In prior renal NC MRA studies (9, 10) motion artifacts have been controlled with navigator-gating, which has been reported to provide more robust motion suppression for liver (19) and biliary tree (20) assessment compared to bellows triggering. However, to our knowledge the reliability of navigator gating versus bellows triggering has not been compared in the context of abdominopelvic MRA. Furthermore, in our application the liver-to-diaphragm interface, where the navigator beam is typically positioned, is far from the magnet isocenter. Consequently, it may be difficult to accurately detect the diaphragmatic position for abdominopelvic NC MRA. In this study no significant motion degradation of image quality was observed using bellows triggering. Respiratory-triggered acquisitions, however, may lead to prolonged scan times in subjects with low breathing rates. In these cases it may be helpful to accelerate the pulse sequence using more advanced view ordering schemes (21, 22) or highly-accelerated parallel imaging (17) with a 32-element coil array at the expense of SNR or spatial resolution.

This technique has several challenging aspects that warrant discussion. As craniocaudal coverage beyond the aortic bifurcation is flow-dependent, insufficient conspicuity of the iliac arteries may be anticipated in patients with severely slow flow. In general, coverage may be extended by prolonging TI at the expense of increased background signal. Indicators of reduced cardiac output (e.g., hypotension, cardiac failure), monitoring heart rate, or measuring arterial flow velocity using phase contrast MRI prior to NC MRA may guide the selection of an appropriate TI and ensure robustness of the technique across a wide spectrum of vascular conditions and blood flow rates.

Secondly, it is important to ensure that the sagittal SS-IR pulse reinverts the entire volume of the abdominal aorta. Failure to do so may reduce arterial visibility distal to the aortic bifurcation. Obtaining scout images of the entire abdominal aorta with coverage up to the heart is therefore necessary for careful planning. The SS-IR pulse also results in a brighter background sagittal “band” that leads to partial visualization of pelvic organs (Fig. 5). Although this band did not degrade diagnostic quality, minimizing the width of the SS-IR pulse to avoid unnecessary enhancement of background and veins is advocated.

Thirdly, the b-SSFP readout is prone to off-resonance artifacts. Severe signal loss caused by bowel gas occurred in two arterial segments. Reduced signal intensity was frequently observed in the suprarenal aorta, likely due to rapid blood flow through an off-resonance region, given that during initial technical optimization of b-SSFP parameters, this signal loss was observed to deteriorate for longer inter-echo spacing. In this study, complete signal voids were prevented by shortening the excitation pulse duration and increasing the receiver bandwidth to achieve a short TR of 3.3 ms. In a small subset of volunteers the artifact was further reduced with ECG-triggering by acquiring the image during diastole. However, combined use of ECG-triggering and respiratory gating significantly prolongs the scan time and is impractical for clinical imaging. Previous inflow-based MRA studies (7–10) have utilized ECG-triggering to include at least one systolic period prior to data acquisition. In this study, TI was longer than a typical cardiac cycle and, therefore, guaranteed one systolic period prior to data acquisition.

To date, only a small number of subjects has been imaged with the proposed pulse sequence. However, initial technical development demonstrates promising results. Further studies in a larger patient population representative of the whole spectrum of vascular disease encountered in clinical practice are necessary to evaluate fully the clinical utility of the pulse sequence and to establish the intra- and inter-instrumental and study variability of the pulse sequence.

In conclusion, an NC MRA pulse sequence using four IR pulses with 3D b-SSFP readout has been developed for imaging of abdominopelvic arteries and appears promising based on the initial experience in seven healthy volunteers and ten patients. The proposed NC MRA provides high spatial resolution visualization of the aortoiliac and renal arteries with comprehensive craniocaudal coverage and sufficient background suppression in clinically feasible scan times.

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

National Institute of Health: HL092439

American Heart Association: 0730143N

References

- 1.Prince MR. Gadolinium-enhanced MR aortography. Radiology. 1994;191(1):155–164. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hany TF, Debatin JF, Leung DA, Pfammatter T. Evaluation of the aortoiliac and renal arteries: comparison of breath-hold, contrast-enhanced, three-dimensional MR angiography with conventional catheter angiography. Radiology. 1997;204(2):357–362. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grobner T, Prischl FC. Gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2007;72(3):260–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyazaki M, Lee VS. Nonenhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2008;248(1):20–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon WT, Sardashti M, Castillo M, Stomp GP. Multiple inversion recovery reduces static tissue signal in angiograms. Magn Reson Med. 1991;18(2):257–268. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910180202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mani S, Pauly J, Conolly S, Meyer C, Nishimura D. Background suppression with multiple inversion recovery nulling: applications to projective angiography. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(6):898–905. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katoh M, Buecker A, Stuber M, Gunther RW, Spuentrup E. Free-breathing renal MR angiography with steady-state free-precession (SSFP) and slab-selective spin inversion: initial results. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1272–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herborn CU, Watkins DM, Runge VM, Gendron JM, Montgomery ML, Naul LG. Renal arteries: comparison of steady-state free precession MR angiography and contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2006;239(1):263–268. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383050058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maki JH, Wilson GJ, Eubank WB, Glickerman DJ, Millan JA, Hoogeveen RM. Navigator-gated MR angiography of the renal arteries: a potential screening tool for renal artery stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):W540–W546. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyttenbach R, Braghetti A, Wyss M, et al. Renal artery assessment with nonenhanced steady-state free precession versus contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2007;245(1):186–195. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443061769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glockner JF, Takahashi N, Kawashima A, et al. Non-contrast renal artery MRA using an inflow inversion recovery steady state free precession technique (Inhance): comparison with 3D contrast-enhanced MRA. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(6):1411–1418. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Berg N, Sheehan J, et al. Renal transplant: nonenhanced renal MR angiography with magnetization-prepared steady-state free precession. Radiology. 2009;251(2):535–542. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2512081094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shonai T, Takahashi T, Ikeguchi H, Miyazaki M, Amano K, Yui M. Improved arterial visibility using short-tau inversion-recovery (STIR) fat suppression in non-contrast-enhanced time-spatial labeling inversion pulse (Time-SLIP) renal MR angiography (MRA) J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(6):1471–1477. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Bazelaire CM, Duhamel GD, Rofsky NM, Alsop DC. MR imaging relaxation times of abdominal and pelvic tissues measured in vivo at 3.0 T: preliminary results. Radiology. 2004;230(3):652–659. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold GE, Han E, Stainsby J, Wright G, Brittain J, Beaulieu C. Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0 T: relaxation times and image contrast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(2):343–351. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker DL, Tsuruda JS, Goodrich KC, Alexander AL, Buswell HR. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of cerebral arteries. A review. Invest Radiol. 1998;33(9):560–572. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, et al. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(6):1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Earls JP, Rofsky NM, DeCorato DR, Krinsky GA, Weinreb JC. Breath-hold single-dose gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR aortography: usefulness of a timing examination and MR power injector. Radiology. 1996;201(3):705–710. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zech CJ, Herrmann KA, Huber A, et al. High-resolution MR-imaging of the liver with T2-weighted sequences using integrated parallel imaging: comparison of prospective motion correction and respiratory triggering. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20(3):443–450. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morita S, Ueno E, Suzuki K, et al. Navigator-triggered prospective acquisition correction (PACE) technique vs. conventional respiratory-triggered technique for free-breathing 3D MRCP: an initial prospective comparative study using healthy volunteers. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(3):673–677. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saranathan M, Bayram E, Glockner J. Group-encoded Ungated Inversion Nulling for Non-contrast Enhancement in the Steady State (GUINNESS): a balanced SSFP-Dixon technique for breath-held non-contrast MRA. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Stockholm, Sweden. 2010. p. 3774. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takei N, Saranathan M, Miyoshi M, Tsukamoto T. Breathhold inhance inflow IR (BH-IFIR) with a novel 3D recessed fan beam view ordering. Proceedings of 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Stockholm, Sweden. 2010. p. 1417. [Google Scholar]