Abstract

Nicotine has been found to produce dose-dependent increases in impulsive choice (preference for smaller, sooner reinforcers relative to larger, later reinforcers) in rats. Such increases could be produced by either of two behavioral mechanisms: (1) an increase in delay discounting (i.e., exacerbating the impact of differences in reinforcer delays) which would increase the value of a sooner reinforcer relative to a later one, or (2) a decrease in magnitude sensitivity (i.e., diminishing the impact of differences in reinforcer magnitudes) which would increase the value of a smaller reinforcer relative to a larger one. To isolate which of these two behavioral mechanisms was likely responsible for nicotine’s effect on impulsive choice, we manipulated reinforcer delay and magnitude using a concurrent, variable interval (VI 30 s, VI 30 s) schedule of reinforcement with 2 groups of Long-Evans rats (n = 6 per group). For one group, choices were made between a 1-s delay and a 9-s delay to 2 food pellets. For a second group, choices were made between 1 pellet and 3 pellets. Nicotine (vehicle, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 0.56 and 0.74 mg/kg) produced dose-dependent decreases in preference for large versus small magnitude reinforcers and had no consistent effect on preference for short versus long delays. This suggests that nicotine decreases sensitivity to reinforcer magnitude.

Keywords: Nicotine, Rats, Intertemporal Choice, Impulsive Choice, Variable Interval, Concurrent Chains

1. Introduction

An intertemporal choice is a choice between two or more alternatives that differ in reinforcer magnitude, reinforcer delay, or both reinforcer magnitude and delay (Loewenstein and Elster, 1992). Perhaps the most commonly studied intertemporal choices are impulsive choices: choices for a smaller-sooner reinforcer over a larger-later reinforcer (for review see Frederick et al., 2002). Anecdotal evidence for a relationship between nicotine and impulsive choice has been accumulating for many years. In 1952 Reader’s Digest published “Cancer by the Carton”, a public alert to the health dangers of smoking. About 15 years later, every package of cigarettes sold in the United States was required to prominently display a health warning. As knowledge of the health benefits of smoking abstinence spread, so too did the prevalence of smoking. Millions of people, on a daily basis, seemed to be choosing a smaller-sooner reinforcer (an immediate cigarette) over a larger-later reinforcer: delayed health benefits.

Bickel et al. (1999) used a delay-discounting task to compare impulsive choices made by smokers, non-smokers, and ex-smokers. In this task, human participants made choices between $1000 after a delay versus some amount of money to be delivered immediately (all consequences were hypothetical). By adjusting the immediate amount of money, Bickel et al. determined the immediate amount of money that was equally preferred to $1000 after a particular delay, a so-called indifference point. This process was repeated using six other delays ranging from 1 week to 25 years, thus yielding seven indifference points. Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic discounting equation was fitted to the data:

| (1) |

where V represents the current value of a delayed reinforcer, M represents the reinforcer magnitude1 (in USD, in this case), D represents the delay to the reinforcer, and k is a free parameter which reflects the rate at which the reinforcer loses value with increases in delay – thus k indicates the degree of delay discounting.

Bickel et al. (1999) found a median k for smokers of 0.054. The degree of discounting for both never-smokers (those who reported to have never smoked a single cigarette) and ex-smokers (those who reported to have smoked previously but abstained for at least 1 year) was identical: 0.007. This correlation between smoking and impulsive choice suggests that either impulsive people are more likely to smoke (and not quit), or that nicotine increases impulsive choice. Dallery and Locey (2005) addressed this issue by examining the effects of acute and chronic nicotine administration on choice in an impulsive-choice procedure with rats. The logic of the impulsive-choice procedure was similar to the human delay-discounting task, with rats making repeated choices between a single food pellet delayed 1 second and 3 food pellets after an adjusting delay. Once an indifference delay was determined for each rat, nicotine was administered to each rat 10 minutes prior to the behavioral task. Dallery and Locey found a dose-dependent increase in impulsive choice for all rats. Although this finding does not eliminate the possibility that more impulsive people are more likely to smoke, it does suggest that those who smoke may become more impulsive as a direct result of the nicotine.

Equation 1 has also proven effective in describing and predicting risky choice (Mazur, 1984). A risky choice is a choice for a more variable rate of reinforcement over a less variable rate of reinforcement (Bateson and Kacelnik, 1995; McNamara and Houston, 1992). If nicotine increases delay discounting (k), then it should increase preference for a variable delay over a fixed delay just as it increases preference for a smaller-sooner reinforcer over a larger-later reinforcer. Locey and Dallery (2009) found no such increases in risky choice, in rats, comparing an adjusting delay to a variable delay of 1 s (p=.5) and 19 s (p=.5). In this initial experiment, a single food pellet was arranged for both alternatives. Locey and Dallery (2009) next replicated the risky-choice experiment but introduced different reinforcer magnitudes: finding the adjusting delay to 3 pellets that was equally preferred to 1 pellet delayed either 1 s or 19 s. With this one change in the procedure, nicotine showed a dose-dependent increase in risky choice very similar to the change observed in the Dallery and Locey (2005) impulsive-choice procedure. These findings suggest that nicotine only affects intertemporal choice when the choice alternatives differ in reinforcer magnitude.

The present experiment was designed to further explore what effects nicotine might have on these two behavioral mechanisms of intertemporal choice: delay sensitivity (or delay discounting2) and magnitude sensitivity. Previous attempts to disambiguate the effects of psychomotor stimulants on sensitivity to reinforcer magnitude and delay have met with mixed results. Pitts and Febbo (2004) found that amphetamine decreased sensitivity to reinforcer delay without impacting sensitivity to reinforcer magnitude. Roesch, Takahashi, Gugsa, Bissonette, and Schoenbaum (2007) found that cocaine increased sensitivity to both reinforcer magnitude and delay. Da Costa Araújo et al. (2010) proposed likely separate neural mechanisms involved with changes in magnitude versus delay sensitivity.

In the present study, concurrent variable interval (VI) schedules of equal duration (30 s) were used to arrange choices between different delays to food in one group and different amounts of food in the other group. If nicotine decreases magnitude sensitivity but has no effect on delay sensitivity, this should be revealed by dose-dependent decreases in relative preference for the lever associated with the large amount of food (for the magnitude group) and no dose-dependent changes in relative preference for the short delay alternative (for the delay group).

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Twelve experimentally naïve Long-Evans hooded male rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in separate cages under a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle with continuous access to water. Each rat was maintained at 85% of its free-feeding weight as determined at postnatal day 150. Supplemental food was provided in each rat’s home cage following each session. The weight of food supplements were calculated daily for each rat, using the difference between each rat’s pre-session weight and its 85% weight.

2.2 Apparatus

Seven experimental chambers (30.5 cm L × 24 cm W × 29 cm H) in sound-attenuating boxes were used. Each chamber had two (2 cm L × 4.5 cm W) non-retractable levers 7 cm from the chamber floor. Each lever required a force of approximately 0.30 N to register a response. A 5 cm × 5 cm × 3 cm food receptacle was located 3.5 cm from each of the two levers and 1.5 cm from the chamber floor. The food receptacle was connected to an automated pellet dispenser containing 45 mg Precision Noyes food pellets (Formula PJPPP). Three horizontally-aligned lights (0.8 cm diameter), separated by 0.7 cm, were centered 7 cm above each lever. From left to right, the lights were colored red, yellow, and green. A ventilation fan within each chamber and white noise from an external speaker masked extraneous sounds. A 28V yellow house light was mounted 1.5 cm from the ceiling on the wall opposite the intelligence panel. Med-PC™ hardware and software controlled data collection and experimental events.

2.3 Procedure

2.3.1 Training

Lever pressing was initially trained on a conjoint fixed-ratio (FR) 1, random-time (RT) 100-s schedule. The houselight was turned on for the duration of each training session. Training trials began with the onset of all three left-lever lights. In the initial trial, both levers were active so that a single response on either lever resulted in immediate delivery of 1 food pellet. The RT schedule was initiated at the beginning of each trial so that a single pellet was delivered, response-independently, approximately every 100 s. Both response-dependent and response-independent food deliveries were accompanied by the termination of all three lever lights. After a 2-s feeding period, the lights were illuminated and a new trial began. After two consecutive presses of one lever, that lever was deactivated until the other lever was pressed. After a total of 60 food deliveries, the session was terminated. Training sessions were conducted for 1 week, at the end of which all response rates were above 10 per minute.

2.3.2 Concurrent VI Baseline

Rats were randomly assigned to either the magnitude (n=6) or delay (n=6) group. In the magnitude group, choices resulted in either 1 pellet (if the “small lever” was chosen) or 3 pellets (if the “large lever” was chosen). In the delay group choices resulted in 2 pellets after a 1-s delay (“short lever”) or a 9-s delay (“long lever”). For both groups, after a 10-m blackout, sessions began with the illumination of the houselight, a yellow light above the left lever, and a red light above the right lever. The houselight remained on for the duration of each session. Each trial consisted of a concurrent (VI 30 s, VI 30 s) schedule. During the concurrent schedule, the two lever lights flashed on a synchronized 0.5-s on-off cycle. The VI schedules were 20-element Fleshler-Hoffman distributions (Fleshler and Hoffman, 1962) from which intervals were selected without replacement to ensure greater daily consistency in reinforcement rate. For the magnitude group, one lever was the “small lever” and one was the “large lever” (counterbalanced across rats; the left lever was “large” for Rats 180-182). For the delay group, one lever was the “short lever” and one was the “long lever” (also counterbalanced; the left lever was “short” for Rats 186-188). Completing the VI on the small or large lever resulted in both lever lights being turned off and an immediate delivery of 1 food pellet (small lever) or 3 food pellets (large lever). For the delay group, completing the VI on the short or long lever produced a 1-s (short lever) or 9-s (long lever) delay. During the delay, the lever light above the not-chosen lever was turned off and the light above the chosen lever remained on for the duration of the delay. The delay ended with the delivery of 2 food pellets regardless of which lever had been chosen. For both groups, a new trial began with the onset of both lever lights 35 s after each VI completion.

VI timers were only active from the onset of a trial to the completion of either VI. New trials began with a new interval for the previously chosen lever and a continuation of the active interval on the not-chosen lever. Sessions were terminated after 20 min (about 30 total trials). The baseline condition lasted for 75 sessions for all rats.

2.3.3 Acute Drug Regimen

The same procedure described in the baseline was used throughout the drug regimen. Nicotine was dissolved in a potassium-phosphate solution (1.13 g/L monobasic KPO4, 7.33 g/L dibasic KPO4, 9 g/L NaCl in distilled H2O; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to adjust pH to 7.4. Subjects were administered nicotine by subcutaneous injection immediately prior to the 10-m pre-session blackout period. Doses were 0.74, 0.56, 0.3, 0.1, and 0.03 mg/kg nicotine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Doses of nicotine were calculated as the base and injection volume was based on body weight at the time of injection (1 ml/kg). Injections occurred twice per week (Wednesday and Saturday). During each phase, rats experienced two cycles of each dose in descending order with each cycle preceded by a vehicle injection.

3. Results

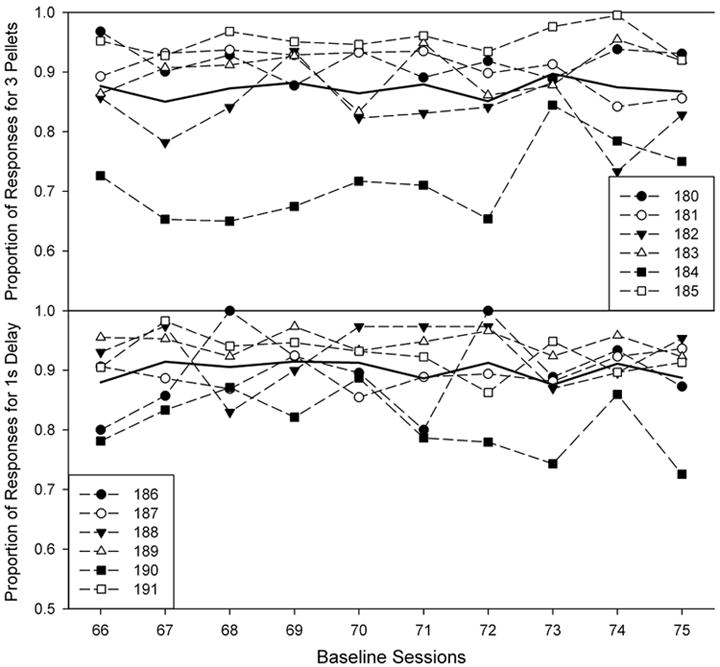

Figure 1 shows the proportion of responses for the preferred alternative during the final 10 sessions of the baseline condition for each rat and for the group mean. The top panel shows response proportions for the large alternative (for the magnitude group) and the bottom panel shows response proportions for the short-delay alternative. Note the y-axes begin at 0.5 as session preference was never for the small or long delay for any rat. Although there is some variability across rats (e.g., Rat 184), preference, in general, was high (80% or more for most rats) and thus similar between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Proportion of responses on the more preferred alternative during the final 10 sessions of the baseline condition for each rat. The top panel shows proportion of responses on the large (3-pellet) lever for all rats in the magnitude group. The bottom panel shows proportion of responses on the short delay (1 s) lever. Note truncated y-axis.

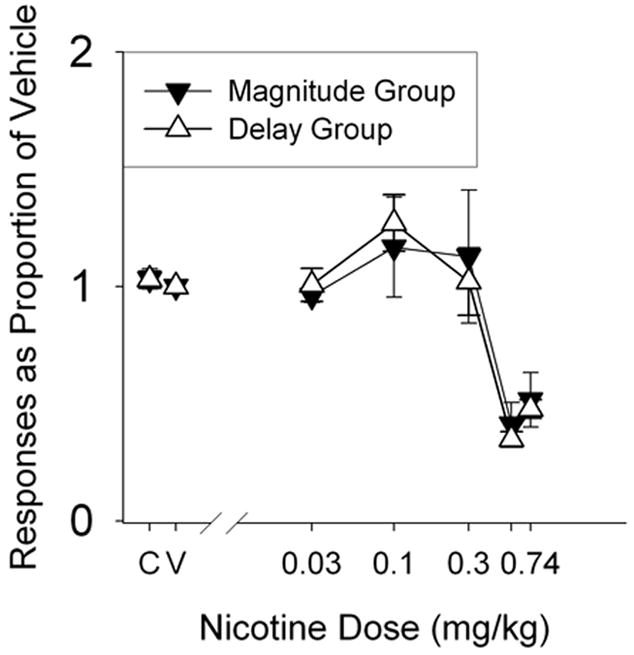

Figure 2 shows the overall rate of responding (on both levers) as a proportion of responding under vehicle as a function of nicotine dose. Filled triangles indicate the mean response rate for the magnitude group and open triangles indicate the mean response rate for the delay group. Although there are some differences across groups, nicotine produced minor increases in response rates at moderate doses and large reductions in responding at large doses.

Figure 2.

Responses on both levers for the magnitude (closed triangles) and delay (open triangles) groups, as a proportion of responses under vehicle, for each nicotine dose. “C” and “V” indicate control (no injection) and vehicle (potassium phosphate) injection, respectively. Vertical lines represent standard errors of the mean.

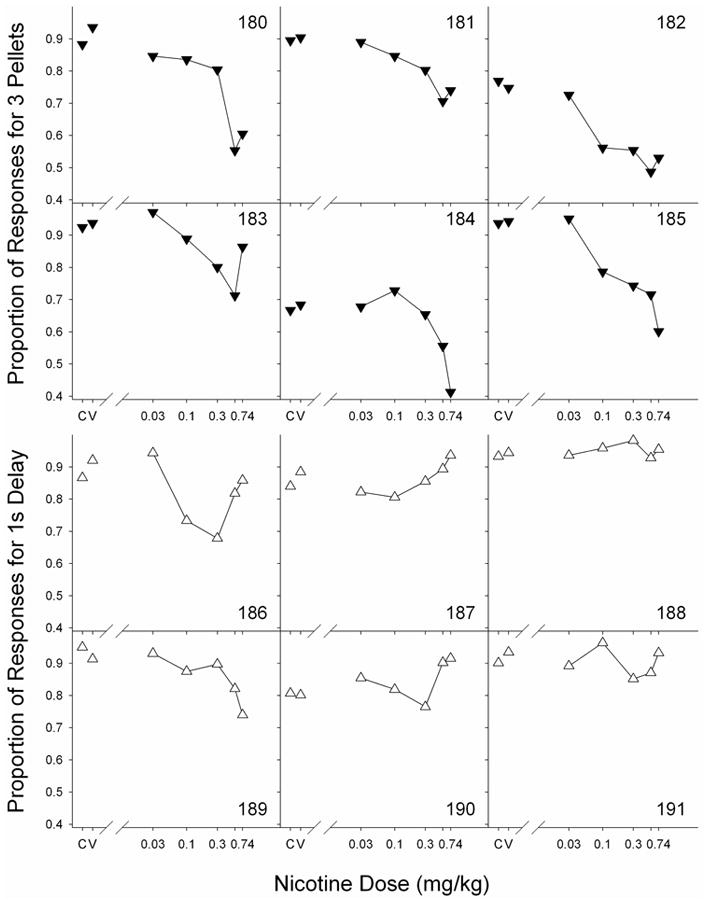

Figure 3 shows the proportion of responses for the preferred alternative, for each rat, as a function of nicotine dose during the acute drug regimen. The top six panels show the proportion of responses for the large alternative (for the magnitude group) and the bottom six panels shows the proportion of responses for the short-delay alternative (for the delay group). “C” and “V” indicate control (no injection) and vehicle (potassium phosphate) injection, respectively. The unlabeled tick mark (between 0.3 and 0.74) indicates 0.56 ml/kg nicotine. Again, note the y-axis begins at 0.4 given that 0.5 would indicate indifference between the two alternatives. For the magnitude group, several rats approached (Rat 180 and 185) or dropped below (Rat 182 and 184) the 0.5 indifference point. The mean results for each group are shown in Figure 4 for ease of comparison. Note the y-axis begins at 0.5 in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Proportion of responses on the typically more preferred alternative as a function of nicotine dose. The top 6 panels show proportion of responses on the large (3-pellet) lever for each of the 6 rats in the magnitude group. The bottom 6 panels show proportion of responses on the short (1-s) lever for each of the 6 rats in the delay group. “C” and “V” indicate control (no injection) and vehicle (potassium phosphate) injection, respectively. Note truncated y-axis.

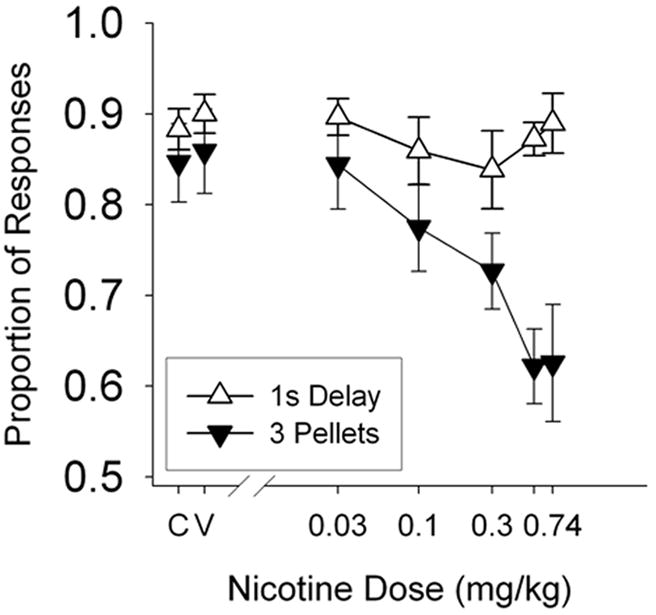

Figure 4.

Proportion of responses on the typically more preferred alternative as a function of nicotine dose. The open triangles show the average proportion of responses on the short (1-s) lever for the delay group. The closed triangles show the average proportion of responses on the large (3-pellet) lever for the magnitude group. “C” and “V” indicate control (no injection) and vehicle (potassium phosphate) injection, respectively. Vertical lines represent standard errors of the mean. Note truncated y-axis.

Regardless of differences in preference under vehicle and no-drug conditions, nicotine produced similar dose-dependent decreases in the proportion of responses for the large lever across all rats in the magnitude group. Friedman ANOVA indicated a significant effect of dose on choice proportions in the magnitude group (F = 30.71, p < 0.0001). Dunn’s multiple-comparison test indicated a significant effect of 0.56 mg/kg and 0.74 mg/kg relative to vehicle (D = 30, 27; p < 0.05). For the delay group, there seemed to be a slight decrease in preference for two rats (Rat 186 and 189) as a function of dose. For the other 4 rats there was either a slight increase or no effect of dose. Friedman ANOVA indicated no significant effect of dose on choice proportions in the delay group (F = 3.5, p = .744). Dunn’s multiple comparison test indicated no significant effects of any dose relative to vehicle (p > 0.05).

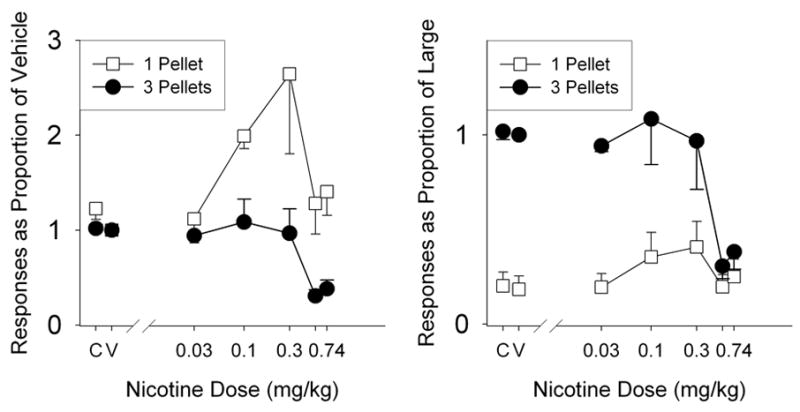

The dose-dependent decrease in preference for the large alternative seen in Figures 3 and 4 could have been accomplished by any of several changes in responding. For instance, both an increase in responding for the small alternative or a decrease in responding for the large alternative could have produced the effects seen in those figures. To more closely examine the effects seen in Figure 3 and 4, Figure 5 shows mean response data for the magnitude group. Both panels show responses for the large lever (closed circles) and small lever (open squares) as a function of nicotine dose during the acute drug regimen. The general effects seen in both panels are representative of the individual effects found for all six rats in the magnitude group. The left panel shows responses as a proportion of responses under vehicle administration (as shown in Figure 2). The right panel shows responses as a proportion of responses on the large lever under vehicle administration. Both panels show that moderate doses of nicotine (0.1 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg) increased responding on the small lever and had little effect on large-lever responding. Large doses of nicotine (0.56 mg/kg and 0.74 mg/kg), however, greatly reduced large lever responding and had little effect on small lever responses, relative to vehicle. As such, the effects seen in Figure 3 seem to be the result of two distinct processes: increases in responding on the small lever at moderate doses and extreme decreases in responding on the large lever at large doses.

Figure 5.

Responses for the large (3-pellet, closed circles) and small (1-pellet, open squares) levers as a proportion of responses on that lever under vehicle (left panel) or as a proportion of responses on the large lever under vehicle (right panel) for each nicotine dose. Vertical lines represent standard errors of the mean. Note the different y-axis in each panel.

4. Discussion

Baseline preference for the large reinforcer and for the short delay was fairly extreme in both groups as shown in Figure 1. This can also be seen for control and vehicle sessions in Figures 3 and 4. For both the magnitude and delay groups, preference during vehicle sessions was at or above 90% for 4 of the 6 rats. As such, the present procedure was not ideal for detecting increases in magnitude or delay sensitivity which could only increase preference by 10% or less for most of the rats. However, given the findings from Locey and Dallery (2009) – which indicated that nicotine likely decreased magnitude sensitivity – the extreme preference during baseline proved useful. Such extreme preference allowed a sensitive measure of the extent to which nicotine might decrease preference towards indifference.

Across rats in the magnitude group, nicotine produced a decrease in preference for the large alternative. Note that the two rats which showed an apparent bias for the lever assigned to the small magnitude (rat 182 and 184 which showed much lower preferences during baseline than all the others), ultimately preferred the small (1-pellet) lever under the most effective dose of nicotine (0.56 ml/kg for Rat 182 and 0.74 ml/kg for Rat 184).

Despite the general lack of effect of nicotine for the delay group, that group proved to be an essential control in the present experiment. Because the procedure used a baseline of extreme preference for the large magnitude reinforcer (an average of about 85% under vehicle and control in Figure 5), any observed change in preference might have been the result of a decrease in stimulus control rather than a decrease in magnitude sensitivity. However, if that were the case, there should have been a comparable decrease for the delay group, but there was not. Similar alternative explanations, such as a simple rate-dependent effect (Branch, 1984; Sanger and Blackman, 1976), are also ruled out due to the similarity of baseline performances and the dissimilarity in the effects of nicotine between the two groups. As such, the present experiment provides support for the interpretation that nicotine increases impulsive choice by decreasing sensitivity to reinforcer magnitude.

Nevertheless, the concurrent-VIs procedure used in this experiment does have its limitations. Due to the performance ceiling produced by the extreme baseline preference, the present procedure would not be ideal for assessing pharmacological manipulations that produce an increase in either magnitude or delay sensitivity. Also, because of the need for a control group to rule out alternative explanations (as described above), the present procedure would also not be ideal for assessing pharmacological manipulations that produce decreases in both magnitude and delay sensitivity. However, for drugs which primarily affect impulsive choice by decreasing delay sensitivity alone or magnitude sensitivity alone, as seems to be the case with nicotine, the present procedure might be a useful choice.

Another limitation of the current procedure was its use of only a single ratio of magnitudes (3:1) and delays (9:1). The 3:1 magnitude ratio was chosen for consistency with previous research (Dallery & Locey, 2005; Locey & Dallery 2009). The 9:1 delay ratio was used because it produced a similar degree of preference for the 1s delay as the 3:1 food ratio produced for the 3-pellet alternative (as shown in Figure 1). Although these ratios produced distinct effects across groups, future research might benefit from multiple paired groups with different ratios that generate less extreme baseline preferences.

Given that Figure 3 (in conjunction with Figure 4) demonstrates that nicotine decreases magnitude sensitivity, the question remains as to how this is accomplished. Is it the case that nicotine increases the apparent magnitude of small reinforcers or does nicotine decrease the apparent magnitude of large reinforcers? The answer appears to be: yes, nicotine does both. Figure 5 shows that under moderate doses (0.1 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg) nicotine increased small lever responses while having no effect on large lever responses. However, at the largest doses (0.56 mg/kg and 0.74 mg/kg) nicotine had no effect on small lever responses but greatly suppressed large lever responses. In the absence of the delay group results, the effects shown in Figure 5 might be interpreted as being unrelated to magnitude sensitivity, and instead being the by-product of moderate doses increasing lower response rates. Similarly, the right panel shows that response rates converge on the largest doses of nicotine, an effect that would be predicted if those doses were eliminating stimulus control. However, such interpretations are not consistent with the lack of similar effects for the delay group – as indicated by the minimal effect on preference in Figures 3 and 4.

Other more complicated explanations could be concocted to account for the differences found between the magnitude and delay groups. However, the most parsimonious explanation would seem to be that (1) nicotine had no consistent effect on sensitivity to reinforcer delay, (2) nicotine decreased sensitivity to reinforcer magnitude, and (3) that decrease in reinforcer magnitude sensitivity was accomplished by both (a) an increase in apparent magnitude of smaller reinforcers at moderate doses of nicotine and (b) a decrease in apparent magnitude of larger reinforcers at larger doses of nicotine. Such an explanation is consistent with the present results, the correlation between smoking and impulsive choice found by Bickel et al. (1999), the nicotine-induced increases in impulsive choice found by Dallery and Locey (2005), the lack of a nicotine effect on risky choice found by Locey and Dallery (2009), and the nicotine-induced increases in risky choice with different reinforcer amounts found by Locey and Dallery (2009).

Statements about changes in impulsive choice are frequently considered synonymous with statements about changes in delay discounting. This is potentially due to the past success of Equation 1 in describing intertemporal choice. If Equation 1 is used to account for how reinforcer delay and reinforcer magnitude contribute to reinforcer value, then any change in value while those parameters are held constant is most easily interpreted as a change in k – the delay discounting parameter. As such, changes in impulsive choice found with opioids (Kirby et al., 1999; Madden et al., 1997, 1999), alcohol (Petry, 2001; Vuchinich and Simpson, 1998), cocaine (Coffey et al., 2003), and nicotine (Bickel et al., 1999; Dallery and Locey, 2005) have all been discussed in terms of correlations between drug use (or administration) and delay discounting. Working within the framework of Equation 1, such conclusions were inevitable. However, the present experiment suggests that a new framework may be needed. Locey and Dallery (2009) proposed adding a magnitude sensitivity parameter to Equation 1 to account for changes in magnitude sensitivity such as those observed in the present experiment.

Given that nicotine decreases magnitude sensitivity, rather than increasing delay discounting, what are the implications of this for smokers? Considering that most smokers maintain only low to moderate doses of nicotine in their body at any given time, nicotine is likely increasing the apparent magnitude (and thus value) of small reinforcers rather than decreasing the apparent magnitude (and thus value) of large reinforcers (as shown in Figure 5). This suggests that smoking cigarettes may be maintained by the indirect effect of nicotine increasing the value of other small reinforcers, rather than the direct effects of nicotine (e.g., the sensation produced by the drug). Indeed, as noted by Caggiula et al. (2001, 2002), this might help to explain why nicotine self-administration is difficult to obtain in rats unless visual stimuli (small reinforcers) are associated with the nicotine infusions (see also Donny et al., 2003; Raiff and Dallery, 2006, 2009).

More research is needed to determine what small reinforcers are enhanced by nicotine. For instance, is the absolute magnitude of the reinforcer relevant or the value relative to other available reinforcers? Is the reinforcer-enhancement effect limited to sucrose pellets and stimulus lights, some broad class of reinforcers, or all reinforcers in general? The findings of Bickel et al. (1999) with hypothetical money suggest a potentially broad scope for this effect, but further empirical work is needed to address the issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julie Marusich, Steve Meredith, and Bethany Raiff for their assistance with this project. This research was supported by grant F31 DA021442 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Mazur’s original (1987) equation used A for reinforcer amount rather than M for reinforcer magnitude. Reinforcer magnitude is used in Equation 1 as it is more generally applicable (e.g., to choices between a whole candy bar and a piece of a candy bar). Similarly, a nicotine effect on magnitude sensitivity might be more plausible than an effect on amount sensitivity. For example, nicotine enhancing the value of small reinforcers seems more likely than nicotine enhancing the value of low-quantity reinforcers. However, the only magnitude manipulation in the current experiment was accomplished by manipulating amount (number of homogenous food pellets), and so whether amount or magnitude is more appropriate in this particular context remains an unanswered empirical question.

Portions of these data were presented at the 2008 meetings of the Association for Behavior Analysis and the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, and the 2010 meeting of the Society for the Quantitative Analysis of Behavior. Portions of this manuscript were included as part of the dissertation of the first author at the University of Florida.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bateson M, Kacelnik A. Preferences for fixed and variable food sources: Variability in amount and delay. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;63:313–329. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.63-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch MN. Rate dependency, behavioral mechanisms, and behavioral pharmacology. J Exp Anal Behav. 1984;42:511–522. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, et al. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Be. 2001;70:515–530. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, et al. Environmental stimuli promote acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:230–237. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2003;11:18–25. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Araújo S, Body S, Valencia Torres L, Olarte Sanchez CM, Bak VK, Deakin JFW, et al. Choice between reinforcer delays versus choice between reinforcer magnitudes: Differential Fos expression in the orbital prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens core. Behav Brain Res. 2010;213:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Locey ML. Effects of acute and chronic nicotine on impulsive choice in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2005;16:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200502000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Delay discounting predicts cigarette smoking in a laboratory model of abstinence reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Evans-Martin FF, Booth S, Gharib MA, et al. Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: Implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:68–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleshler M, Hoffman HS. A progression for generating variable-interval schedules. J Exp Anal Behav. 1962;5:529–530. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O’Donoghue T. Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. J Econ Lit. 2002;40:351–401. [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. Aperiodicity as a factor in choice. J Exp Anal Behav. 1964a;7:179–182. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1964.7-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. Secondary reinforcement and rate of primary reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1964b;7:27–36. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1964.7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locey ML, Dallery J. Isolating behavioral mechanisms of intertemporal choice: Nicotine effects on delay discounting and amount sensitivity. J Exp Anal Behav. 2009;91:213–223. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2009.91-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Elster J. Choice over time. Russell Sage; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using controls participants: Drug and monetary rewards. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 1997;5:256–262. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK, Jacobs EA. Discounting of delayed rewards in opioid-dependent outpatients: Exponential or hyperbolic discounting functions. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 1999;7:284–293. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. Tests of an equivalence rule for fixed and variable reinforcer delays. J Exp Psychol Anim B. 1984;10:426–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazur JE, Nevin JA, Rachlin H, editors. Quantitative analyses of behavior: the effects of delay and of intervening events on reinforcement value. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, N.J.: 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara JM, Houston AI. Risk-sensitive foraging: A review of the theory. BB Math Biol. 1992;54:355–378. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RC, Febbo SM. Quantitative analyses of methamphetamine’s effects on self-control choices: Implications for elucidating behavioral mechanisms of drug action. Behav Process. 2004;66:213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Judgment, decision, and choice. Freeman; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Raiff BR, Dallery J. Effects of acute and chronic nicotine on responses maintained by primary and conditioned reinforcers in rats. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2006;14:296–305. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiff BR, Dallery J. Responding maintained by primary reinforcing visual stimuli is increased by nicotine administration in rats. Behav Process. 2009;82:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch MR, Takahashi Y, Gugsa N, Bissonette GB, Schoenbaum G. Previous cocaine exposure makes rats hypersensitive to both delay and reward magnitude. J Neurosci. 2007;27:245–250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4080-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger DJ, Blackman DE. Rate-dependent effects of drugs: A review of the literature. Pharmacol Biochem Be. 1976;4:73–83. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(76)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Diagramming Schedules of Reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1958;1:67–68. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1958.1-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 1998;6:292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]