Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterised by a strong desmoplastic reaction where the stromal compartment often accounts for more than half of the tumor volume. Pancreatic stellate cells (PSC) are a central mediator of desmoplasia. There is increasing evidence that the desmoplasia is contributing to the poor therapeutic response of PDAC. We show that PSC promote radioprotection and stimulate proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells (PCC) in direct coculture. Our in vivo studies demonstrate PSC dependent radioprotection in response to a single dose and to fractionated radiation. Abrogating β1-integrin signaling abolishes the PSC mediated radioprotection in PCC. Furthermore, this effect is independent of PI3K, but dependent on FAK. Taken together we demonstrate for the first time that PSC promote radioprotection of PCC in a β1-integrin dependent manner.

Keywords: Pancreatic stellate cells, radiation, pancreatic cancer, stroma, β1-integrin

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the major malignancies in the Western world (1). PDAC is characterised by a late stage diagnosis, rapid development of metastasis (1) and a pronounced fibrotic reaction known as desmoplasia (2). This enrichment and activation of the stromal compartment surrounding and infiltrating the cancer is believed to have a detrimental effect on the response to chemo- and radiotherapy (3, 4). Nevertheless, radiotherapy was shown to be effective especially in the treatment of locally advanced disease as recently shown in a randomised trial (ECOG-4201) and even complete pathological treatment response was reported (5).

In recent years pancreatic stellate cells (PSC) gained interest as these are believed to drive the desmoplastic reaction. PSC differentiate from a quiescent state into activated myofibroblast-like cells in response to oxidative stress as well as secreted growth factors and cytokines from tumor cells (3). Activated PSC produce extra cellular matrix (ECM) proteins that modulate the stroma and stimulate fibrosis (6-8). PSC moreover express various growth factors, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases involved in stimulating proliferation, migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells (PCC) (9, 10). Altogether, it is becoming increasingly clear that PSC contribute to the malignant phenotype of PDAC.

Cell adhesion to the ECM is crucial for regulation of tissue homoestasis and cell fate, and is mediated through the integrin family of transmembrane surface receptors (11). Integrins are known to modulate the cellular response to genotoxic injury, and β1-integrin in particular is implicated in mediating cell survival in response to radiation in different cancer cell lines (12-14). Hence, desmoplasia-induced changes in composition of the ECM surrounding PDAC are likely to impact on the PCC through integrin signaling.

In this study we investigated the effects of radiation on PCC in the presence of a stromal component, the PSC, in vitro and in vivo. In both conditions PSC mediated radioprotection of PCC.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Panc-1 and MiaPaCa-2 were obtained from ATCC and PSN-1 through an MTA with Merck & Co., Inc. (West Point, PA). LTC-14 was kindly provided by Dr. G. Sparmann, Rostock, Germany. The human pancreatic stellate cell line, hPSC, and cell culture conditions are described in Suppl. Figure 1.

Clonogenic survival assay

For coculture assays hPSC were allowed to attach ON prior to plating of PCC in fresh medium. For LTC-14-PCC cocultures both cell lines were seeded simultaneously. All mono- and cocultures were incubated for 5h prior to radiation in a cesium source irradiator (IBL 637, CIS Bio International) at a dose rate of 0.98 Gy/min. β1-integrin blocking antibody (MAB17781, R&D Systems) or 20μM LY294002 (Calbiochem) was added to cells 2h prior to radiation. Colonies were stained with crystal violet (Pro-Lab Diagnostia) 10–14 days later and counted. The surviving fraction was calculated as described previously (15). The protection enhancement ratio (PER) was used to quantify radiosensitization and was calculated as described in Suppl. Figure 4.

In vivo experiments

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with current UK legislation under an approved project license. Female nude mice were divided into two groups receiving injections subcutaneously into the flank with 1*106 PSN-1 with or without 4*106 LTC-14. Animals were assigned randomly to receive a 6 Gy single dose in one experiment or 3.5 Gy on three consecutive days in another experiment under anaesthesia when the tumors had attained a volume of 50 mm3. Tumor growth was measured regularly by callipers. In the single dose experiment one animal in the PSN-1 control group was terminated at day 5 due to gait restraint. The tumor growth curve was extrapolated to day 7 by fitting to the linear growth equation (y=ax+b) according to the trend of the other five growth curves in this group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism. Comparisons were made between whole clonogenic survival curves by use of the F-test. For all other significance testing a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post test was used. Statistical difference was denoted as follows: *: P<0.05, **: P<0.001, ***: P<0.0001. All data is presented as mean ± standard error.

siRNA transfection

Cells were transfected with β1-integrin and/or FAK siGENOME SMART pool or control siRNA (Dharmacon). DharmaFect 4 (Dharmacon) and siRNA were used according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Cells were added to the transfection mix and incubated for 48 hrs before seeding for clonogenic assays or lysed for Western blot.

Western blotting

As described previously (15). Antibodies used were β1-integrin (ab52971, Abcam), Akt, p-Akt and FAK (#9272, #9271 and #3285, Cell Signaling), P-FAK (Invitrogen), GAPDH and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Results

Coculture of tumor and stellate cells

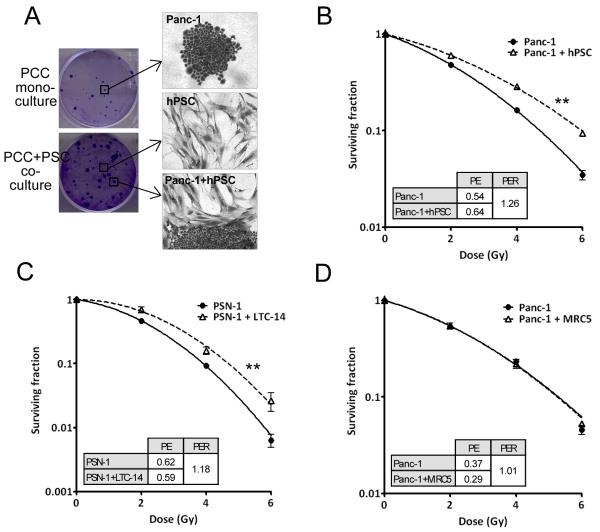

We set up a clonogenic survival assay for PCC directly cocultured with PSC. PSC were grown as a monolayer prior to seeding of PCC. The PCC colonies grown on top were clearly distinguishable from the PSC monolayer by means of crystal violet staining (Figure 1A) and by immunofluorescence staining with PSC and PCC specific markers (Suppl Figure 1A). The larger size of PCC colonies in cocultured dishes indicated increased PCC proliferation (Figure 1A), which was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis showing fewer cells in G1 (Suppl. Figure 1B). This observation is in line with previous reports demonstrating increased PCC proliferation in response to PSC conditioned medium (9, 10).

Figure 1.

A, Tumor cell colonies from a clonogenic survival assay with PCC in monoculture and PCC in coculture with PSC. Clonogenic survival curves of B, Panc-1 coculture with hPSC. **, F-test P=0.001, and C, PSN-1 coculture with LTC-14. **, F-test P=0.001. D, Panc-1 coculture with MRC5 fibroblasts. Graphs are representative of at least three independent experiments. Error bars are contained within the points. Inserts show PE: plating efficiency and PER: protection enhancement ratio.

Radiosensitivity studies

The radiosensitivity of different PCC was investigated in monoculture and in coculture with PSC. We discovered that PSC increased the clonogenic survival of PCC, an observation that applied to several different PSC (hPSC and LTC-14) and PCC (Panc-1, PSN-1 and MiaPaCa-2) (Figure 1B,C, Suppl. Figure 2A). The clonogenic survival curves of PSC alone are shown in the supplementary data (Suppl. Figure 2B). Conditioned PSC medium did not radioprotect the PCC but a PSC feeder layer created by giving a lethal dose of radiation was indeed able to do so suggesting a direct contact between the cells is required (Suppl. Figure 2C-F). The increased PCC survival was specific to PSC as the human fibroblast cell line MRC5 did not change the response to radiation (Figure 1D). Together these data demonstrate that the survival of PCC after radiation is enhanced by direct coculture with PSC, and that this response is specific to PSC rather than a general mesenchymal cell response.

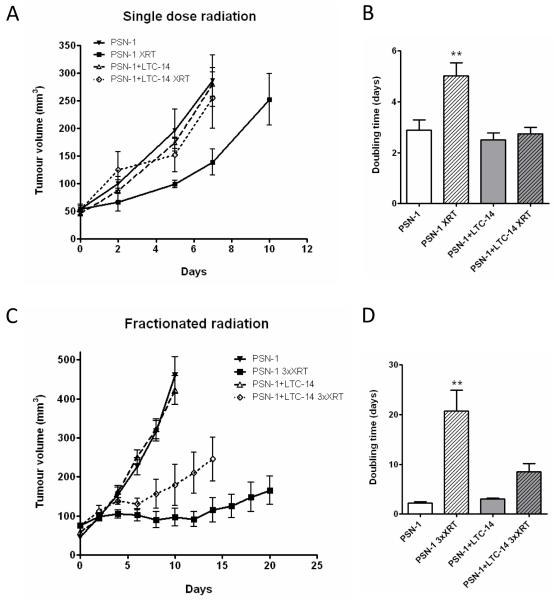

Tumor response to radiation in vivo

We investigated the effect of PSC on PCC in vivo, and observed a faster tumor development in animals coinjected with PSN-1 and LTC-14 compared to PSN-1 alone. PSN-1 tumors on average took 23 days to reach 50 mm3 versus 15 days for PSN-1+LTC-14 tumors (t-test, p=0.008). Importantly, PSC alone did not form tumors during a six month period. A single dose radiation induced a growth delay only in the PCC tumors (Figure 2A). Fractionated radiation induced a growth delay in both groups but the response was less pronounced in the PCC+PSC group (Figure 2C). A significant increase in the tumor doubling time was observed in the PSN-1+XRT group only in both experiments (Figure 2B, D). These findings are in accordance with our tissue culture observations (Figure 1) and confirm that PSC have a radioprotective effect on PCC both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2.

Tumor growth was measured in mice injected with PSN-1 alone or PSN-1+LTC-14. The animals were randomised and radiated when tumor volume reached 50 mm3. A, Single dose of 6 Gy (XRT), n=6 animals per group. B, Tumor doubling time. **, ANOVA, P<0.001 C, Three 3.5 Gy doses given on consecutive days (3xXRT), n=4 or 5 animals per group. D, as in B.

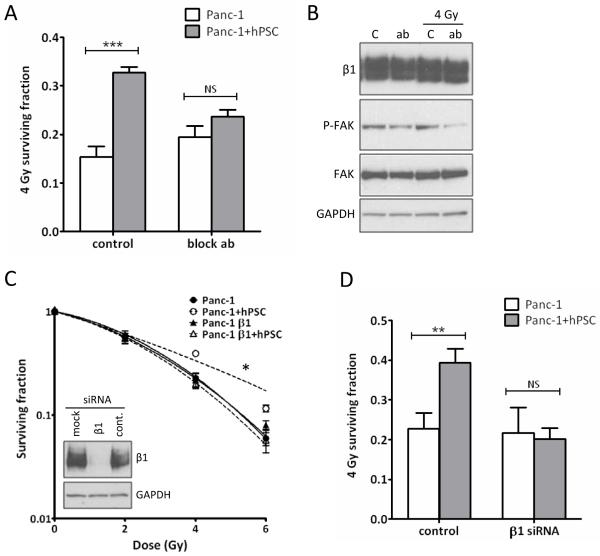

Integrin signaling

PSC produce ECM proteins known to activate signaling through β1-integrins (16). We therefore treated mono- or cocultured PCC with a β1-integrin blocking antibody prior to radiation and the PSC-mediated radioprotective effect was significantly reduced (Figure 3A). Phosphorylated FAK, a downstream adaptor protein of β1-integrin, was reduced after exposure to the blocking antibody (Figure 3B). The effect of blocking β1-integrin in PCC only was investigated by siRNA knock down (Figure 3C). When cocultured with untransfected hPSC, Panc-1 cells were sensitized to radiation (Figure 3C,D). The overall survival of monocultured Panc-1 remained unchanged in response to both blocking antibody and β1-integrin siRNA (Figure 3A,D). We conclude that β1-integrin in PCC is involved in the PSC-mediated radioprotection. This observation could not be attributed to changes in surface expression of β1-integrin in PCC and PSC in mono- and coculture (Suppl. Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Blocking β1-integrin signaling. A, The 4 Gy surviving fraction of mono- versus cocultured Panc-1 cells treated with β1-integrin blocking antibody. ***, ANOVA, P<0.0001. B, Western blot of Panc-1 exposed to blocking antibody (ab) for 2 hrs (two left lanes) and for 2 hrs prior to 4 Gy radiation followed by 16 hrs incubation (two right lanes). C: no antibody control. C, Western blot of β1-integrin siRNA transfected Panc-1 and clonogenic survival assay of transfected cells cocultured with hPSC. *, F-test P=0.039. D, 4 Gy surviving fraction from C. **, ANOVA, P<0.001. NS: not significant. PE and PER values are in Suppl. Figure 4.

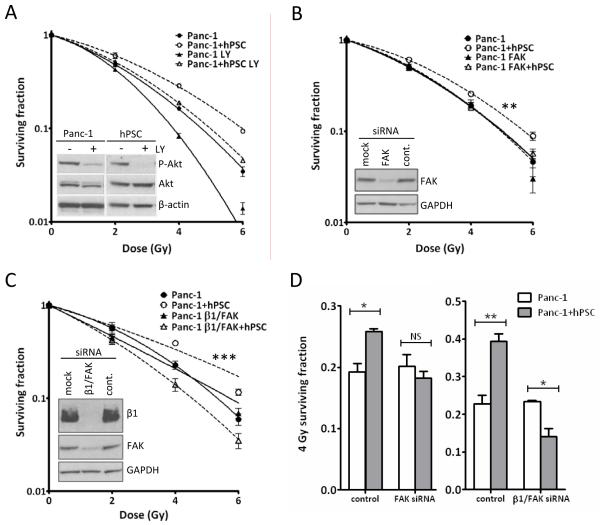

Downstream signaling from β1-integrin

To determine the intracellular signaling involved in this response we blocked two downstream kinases of β1-integrin, Akt and FAK. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 reduced P-Akt levels in both Panc-1 and hPSC (Figure 4A). LY294002 sensitized mono- and cocultured Panc-1 to radiation (Figure 4A), but did not affect the radiosensitivity of the hPSC (data not shown). Blocking PI3K did not impact on the radioprotective effect of PSC precluding Akt as the downstream kinase of β1-integrin mediating the stroma response in the tumor cells. Knockdown of FAK had no effect on the radiation response of Panc-1, but prevented PSC mediated radioprotection (Figure 4B,D). β1-integrin/FAK double knockdown likewise caused loss of the PSC-mediated radioprotection without a significant effect on the radiosensitivity of Panc-1 in monoculture (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Signaling downstream of β1-integrin. Clonogenic survival curves of Panc-1 cells in response to A, 2 hrs LY294002 treatment, B, FAK siRNA knockdown. **, F-test P=0.0004 and C, β1-integrin/FAK double knock down. ***, F-test P<0.0001. Graphs are representative of at least two independent experiments. Inserted Western blots show response to the given treatments. D, 4 Gy surviving fractions from B (*, ANOVA, P<0.05) and C (**, ANOVA, P<0.001 and *, P<0.05). NS: not significant.

Discussion

The tumor microenvironment is an important component when studying PCC and their response to therapeutics. It is now accepted that PSC stimulate the growth of PCC and vice versa hence contributing to the malignant phenotype of PCC (3, 9, 10), which was confirmed in our study. We are the first to report increased radiation survival of PCC in coculture with PSC in clonogenic assays, the gold standard to measure radiosensitivity, as well as in vivo using a single dose and fractionated radiation.

Conditioned medium from radiated PSC was reported to enhance proliferation of PCC (17), but clonogenic survival of PCC was not altered by conditioned media from PSC in our hands. Furthermore, PCC were protected from postradiation (100 Gy) apoptosis by conditioned media from PSC (9). The significance of these data is however limited because proliferation does not predict survival after radiotherapy (18) and apoptosis is not a predominant type of cell death after radiation in solid tumors (19). We investigated whether radiation-induced DNA damage was repaired more efficiently in PCC in the presence of PSC, as this could improve survival. Residual 53BP1 foci in PCC were counted up to 24 hours after radiation of mono- and cocultures (Suppl. Figure 3). Our findings revealed no differences in DNA repair kinetics concluding that they do not form part of this radioprotective response.

Our in vivo data showed that the doubling time of PCC tumors increased significantly in response to single dose radiation compared to that of PCC+PSC tumors. Importantly, the observed radioprotective effect of PSC on PCC could neither be attributed to a significant contribution of the PSC to the tumour volume at the time of randomisation (Suppl. Figure 6) nor to a higher metabolic demand on the tissue due to the difference of total cell number injected (Suppl. Figure 7). Fractionated radiation further increased the observed difference, and this is clinically important because typically patients have fractionated radiotherapy over 5-6 weeks. Additionally, radiotherapy is known to enhance desmoplasia in PDAC(17). Therefore, inhibition of the radioprotective effect of PSC is predicted to increase the efficacy of radiotherapy for patients with PDAC throughout the entire course of therapy.

We aimed to identify elements of heterotypic signaling, which are specifically relevant for this form of microenvironment-mediated therapeutic resistance. We demonstrated that β1-integrin signaling in tumor cells is required for radioprotection by PSC. Integrins feed information to cancer cells from both ECM adhesion and soluble factors to be interpreted in the full context as a checkpoint for cell fate (11). The malignant phenotype of PCC grown on collagen I in vitro is enhanced and α2β1 integrin signaling is involved in this response (6, 16). These results point towards integrins as crucial components in PSC-PCC communication.

We further identified FAK as a downstream effector kinase in this response. Interestingly, dual β1-integrin/FAK knowkdown further radiosentised PCC in the presence of PSC whereas it did not in PCC only. This implies that β1-integrin and FAK do not act purely within the same cascade but also in parallel and that dual inhibition appears to block a rescue pathway. The mechanism behind this response will be investigated further in future in vivo experiments.

Altogether we provide evidence for PSC-mediated radioprotection of PCC through β1-integrin-FAK signaling. Targeting this pathway is predicted to enhance radiosensitiviy of PCC and may be successful to enhance the effects of radiotherapy in patients with PDAC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by MRC grant H3RMWX0

References

- 1.Philip PA, Mooney M, Jaffe D, Eckhardt G, Moore M, Meropol N, et al. Consensus report of the national cancer institute clinical trials planning meeting on pancreas cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5660–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masamune A, Watanabe T, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. Roles of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachem MG, Zhou S, Buck K, Schneiderhan W, Siech M. Pancreatic stellate cells--role in pancreas cancer. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery / Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2008;393:891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science (New York, NY. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunner TB, Scott-Brown M. The role of radiotherapy in multimodal treatment of pancreatic carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong T, Packham G, Murphy LB, Bateman AC, Conti JA, Fine DR, et al. Type I collagen promotes the malignant phenotype of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7427–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apte MV, Park S, Phillips PA, Santucci N, Goldstein D, Kumar RK, et al. Desmoplastic reaction in pancreatic cancer: role of pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas. 2004;29:179–87. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachem MG, Schunemann M, Ramadani M, Siech M, Beger H, Buck A, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:907–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A, et al. Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:918–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vonlaufen A, Joshi S, Qu C, Phillips PA, Xu Z, Parker NR, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells: partners in crime with pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2085–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Streuli CH, Akhtar N. Signal co-operation between integrins and other receptor systems. Biochem J. 2009;418:491–506. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordes N, Seidler J, Durzok R, Geinitz H, Brakebusch C. beta1-integrin-mediated signaling essentially contributes to cell survival after radiation-induced genotoxic injury. Oncogene. 2006;25:1378–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park CC, Zhang HJ, Yao ES, Park CJ, Bissell MJ. Beta1 integrin inhibition dramatically enhances radiotherapy efficacy in human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4398–405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodkinson PS, Elliott T, Wong WS, Rintoul RC, Mackinnon AC, Haslett C, et al. ECM overrides DNA damage-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in small-cell lung cancer cells through beta1 integrin-dependent activation of PI3-kinase. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1776–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantoni TS, Schendel RR, Rodel F, Niedobitek G, Al-Assar O, Masamune A, et al. Stromal SPARC expression and patient survival after chemoradiation for non-resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7 doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.11.6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grzesiak JJ, Bouvet M. The alpha2beta1 integrin mediates the malignant phenotype on type I collagen in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1311–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erkan M, Kleeff J, Gorbachevski A, Reiser C, Mitkus T, Esposito I, et al. Periostin creates a tumor-supportive microenvironment in the pancreas by sustaining fibrogenic stellate cell activity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1447–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banasiak D, Barnetson AR, Odell RA, Mameghan H, Russell PJ. Comparison between the clonogenic, MTT, and SRB assays for determining radiosensitivity in a panel of human bladder cancer cell lines and a ureteral cell line. Radiation oncology investigations. 1999;7:77–85. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6823(1999)7:2<77::AID-ROI3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown JM, Wouters BG. Apoptosis, p53, and tumor cell sensitivity to anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1391–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.