Abstract

Objective

There are numerous challenges to successfully integrating palliative care in the ICU. Our primary goal was to describe and compare the quality of palliative care delivered in an ICU as rated by physicians and nurses working in that ICU.

Design

Multi-site study using self-report questionnaires.

Setting

Thirteen hospitals throughout the United States.

Participants

Convenience sample of 188 physicians working in critical care (attending physicians, critical care fellows, resident physicians) and 289 critical care nurses.

Measurements

Clinicians provided overall ratings of the care delivered by either nurses or physicians in their ICU for each of seven domains of ICU palliative care using a 0–10 scale (0 indicating the worst possible and 10 indicating the best possible care). Analyses included descriptive statistics to characterize measurement characteristics of the 10 items, paired Wilcoxon tests comparing item ratings for the domain of symptom management with all other item ratings, and regression analyses assessing differences in ratings within and between clinical disciplines. We used p<0.001 to denote statistical significance to address multiple comparisons.

Main Results

The ten items demonstrated good content validity with few missing responses, ceiling or floor effects. Items receiving the lowest ratings assessed spiritual support for families, emotional support for ICU clinicians, and palliative-care education for ICU clinicians. All but two items were rated significantly lower than the item assessing symptom management (p<0.001). Nurses rated nursing care significantly higher (p<0.001) than physicians rated physician care in five domains. In addition, while nurses and physicians gave comparable ratings to palliative care delivered by nurses, nurses’ and physicians’ ratings of physician care were significantly different, with nurse ratings of this care lower than physician ratings on all but one domain.

Conclusion

Our study supports the content validity of the 10 overall rating items and supports the need for improvement in several aspects of palliative care including spiritual support for families, emotional support for clinicians, and clinician education about palliative care in the ICU. Further, our findings provide some preliminary support for surveying ICU clinicians as one way to assess the quality of palliative care in the ICU.

Keywords: palliative care, end-of-life care, dying, death, quality of care

Introduction

Approximately 20% of Americans die in the ICU or shortly after a stay in the ICU and therefore palliative care is an important aspect of an ICU clinician’s daily scope of practice.1 The importance of palliative care in the ICU has also been supported by a number of recent statements from critical care professional societies,2, 3 and its successful integration into care in the ICU has been shown to be associated with a number of key outcomes. These outcomes include improved quality of dying and death, shorter ICU length of stay for patients who die in the ICU, and reductions in family psychological symptoms following a patient’s death.4–7

In order to improve palliative care in ICU settings, it is necessary to specify and measure those aspects of palliative care that contribute to high quality care.8 A recent report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Critical Care End-of-Life Peer Work Group identified seven specific palliative care domains.9 These domains were developed through extensive literature review as well as iterative and collaborative expert consensus process. The domains included: 1) patient- and family-centered decision making; 2) communication within the team and with patients and families; 3) continuity of care; 4) emotional and practical support for families; 5) symptom management and comfort care; 6) spiritual support of patients and families; and 7) emotional and organizational support for ICU clinicians.10 Such domains form the basis for a comprehensive approach to measuring the quality of palliative care in the ICU.

In addition to developing measurement items that represent these domains, it is also important to select respondents who have participated in and can evaluate palliative care in the ICU. Patients and their families are important sources of such evaluation and should generally be considered the “gold standard”. Unfortunately, patient and family report data are often challenging to obtain. Patients are typically too ill or sedated to respond to surveys.11 Family members are often dealing with depression and anxiety12 and their perspectives may represent their own experiences, rather than those of the patient.13–16 There is also evidence that bias introduced by low family response rates results in an over-estimation of the quality of palliative care in the ICU.17 In addition, evaluations by patients and families may be limited by the lack of prior experience with ICU care or by low expectations for quality of care. ICU clinicians are less likely to have these limitations. Prior studies have shown that family members have given higher ratings of quality of end-of-life care than ICU nurses or resident physicians, suggesting that clinicians may be more critical raters of the quality of ICU palliative care.18, 19 Finally, although the medical record may provide useful information about quality of end-of-life care, it can only reflect the documentation of such care and such documentation may be limited.20, 21

Clinicians are in a unique position to evaluate the quality of palliative care. They can place their assessments within a framework of prior experiences and may be able to assess care that is not always well documented in the medical record. Some prior studies have examined clinicians’ ratings of quality of dying and death for critically ill patients, 19, 22, 23 but to date there are few assessments of ICU clinicians’ perceptions of palliative care quality in their ICUs. 24, 25 These prior studies have shown interesting differences between ratings of nurses and the rating of physicians, suggesting this comparison may be instructive.

In this study, we piloted ten items providing overall ratings of the quality of palliative care in the ICU from physicians and nurses. These items were based on the seven domains described above.9 Our goal was two-fold: 1) to examine the items’ content validity; and 2) to use the items to describe the quality of palliative care in the ICU from the perspective of ICU physicians and nurses in order to identify potential targets for quality improvement. To explore the items’ content validity, we examined each item’s distributional characteristics. To describe the quality of palliative care, we examined 1) mean scores for each item as compared with the item assessing symptom management, with the rationale that that symptom management is a standard and primary skill of palliative care;2, 26–28 2) item ratings of the quality of palliative care delivered by the respondent’s discipline (e.g., physicians rating physician care) as compared with ratings by respondents from another discipline (e.g., nurses rating physician care); and 3) within the physician group, house staff item ratings as compared with attending physician item ratings.

Methods

Sample

Using a self-report questionnaire, we conducted a multi-site study with nurses, attending physicians and house staff (i.e., residents, fellows) assessing the quality of palliative care provided by physicians and nurses in their ICU. Thirteen hospitals throughout the United States participated as part of a convenience sample. Seven of the thirteen sites were university-affiliated medical centers and the remaining were community hospitals.

Survey Items

The ten items that are used in this study were selected from a longer survey that included 61 items in the physician version and 63 items in nurse version. The full set of items was designed to sample each of the seven domains of quality care developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Critical Care End-of-Life Peer Work Group and was based on the 53 items in that report.9 Investigators (JRC, JN, JL, DER, MML) piloted the items through repeated administration, developing the questionnaire’s face validity through this process. Items were written to assess care provided in the ICU generally rather than to assess the care of a specific patient.

Prior to selecting the summary items as the focus of this analysis, we completed factor analytic studies using all items in an attempt to identify empirically-derived domains and consider creating a multi-item scale that produced a single score. These analyses did not identify solutions that met acceptable standards for scale development (data not shown). Consequently, we chose to report only scores for the summary-item ratings that were developed to represent each of the seven domains and we do not propose development of a multi-item score from these items at this time.

The summary items (the focus of the present report) asked respondents to evaluate the overall quality of care in each of the seven quality-of-care domains. In four of the domains, a single question is used; in three of the domains, two questions are used. The domains with two items allowed us to assess dual features of that domain (i.e., continuity of care among caregivers or colleagues, communication of goals of care with team or patients/families; emotional or educational support to ICU clinicians). Each of the ten overall rating items were examined separately. The summary rating items use a 0–10 scale with 0 indicating the worst possible care and 10 indicating the best possible care. Respondents were asked to rate each of the 10 summary items once for care delivered by doctors and once for care delivered by nurses. The full survey is in the public domain and available online (https://depts.washington.edu/eolcare).

Data Collection

Questionnaire data were collected from November, 2003 to December, 2004. At each ICU, we contacted medical and nursing directors or their designees to gain permission and access to physicians and nurses working in the ICU. A research nurse performed site visits over one to two days at each participating ICU. To encourage participation, she provided lunch at each site and invited clinicians to complete surveys at that time. In addition, surveys were available at the nursing stations of each ICU for clinicians who could not attend the lunch session. All site visits occurred during daytime hours.

Volunteer participants completed questionnaires anonymously and no sign-ups or logs were kept of potential participants. It was not feasible to assess the number of potentially eligible clinicians at each site due to the diverse staffing patterns in the different ICUs. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rhode Island Hospital and approved or determined to be exempt from institutional review at the other institutions.

Analyses

Content validity

Content validity is supported when an instrument is appropriate relative to its intended use. 29 Appropriateness may be determined by examining the distributional characteristics of an instrument or items; these characteristics may include the number of valid responses, the use of the full range of scores with little skew, and few ceiling scores (scores at the very top of the response scale) and floor scores (scores at the very bottom of the response scale).30 We used descriptive statistics (% missing responses, skew, % scores of “0”, % scores of “10”) to assess each item’s performance in comparison with the following standards: 1) 5% or less missing responses; 2) distributions with skew less than +/−1.00; 3) 5% or less of floor scores of “0”; and 4) 5% or less of ceiling scores of “10”.

Quality of palliative care

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) were used to assess survey responses provided by physicians and nurses for both their own evaluations and evaluations of care provided by other clinicians. To compare quality ratings for all domains with ratings of symptom management, we used paired Wilcoxon tests. To compare ratings within and across disciplines, we used robust regression analyses controlling for site with dummy indicators and respondent type (physician vs. nurse or house staff vs. attending) as the predictor. Because these items have not been previously validated, we do not have an estimate of their minimum clinically important difference. We have therefore reported effect sizes using Cohen’s d. We chose a stringent p value for significance (p<=0.001) to account for the large number of comparisons.

Results

A total of 289 nurses and 188 physicians (83 attending physicians, 104 residents/fellows, 1 physician with unreported status) completed the survey at 15 ICUs in 13 institutions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| ICU Type | Academic Affiliation | # Beds | Physicians (n=188) | Nurses (n=289) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | ||||

| Site 1 | X | 8 | 9 | 23 |

| Site 2 | X | 8 | 19 | 22 |

| Site 3 | X | 14 | 22 | 23 |

| Site 4 | X | 14 | 19 | 21 |

| Site 5 | X | 18 | 6 | 16 |

| Site 6 | X | 14 | 7 | 20 |

| Site 7 | 12 | 17 | 13 | |

| Surgical | ||||

| Site 8 | X | 24 | 16 | 17 |

| Site 9 | X | 16 | 13 | 30 |

| General/Combined/Other | ||||

| Site 10 | 16 | 20 | 20 | |

| Site 11 | 9 | 7 | 11 | |

| Site 12 | 27 | 13 | 22 | |

| Site 13 | 24 | 7 | 21 | |

| Site 14 | 12 | 9 | 14 | |

| Site 15 | X | 9 | 4 | 16 |

Content validity

Item completion rates for all items and for all respondents (i.e., physicians, nurses) ranged from 94.1% to 99.5% for physicians and 95.8% to 99.7% for nurses. (Table 2) With the exception of two items reported by physicians, all items met our expectation that 95% or more of participants answered each item (i.e., “How well does your organization support the provision of emotional support for nurses caring for dying patients?”, “How well does your organization support the provision of education about palliative care for nurses?”). Item distributions generally met the requirement of skew not exceeding +/− I.00 with the following exceptions: two items answered by physician respondents assessing continuity of care (nurses’ communication with colleagues about patient/family emotional needs, physicians’ communication of goals of care to next caregivers) and four items answered by nurse respondents assessing continuity of care (nurses’ communication with colleagues about patient/family emotional needs; nurses’ attention to patients/families’ emotional and practical needs; nurses’ symptom management and comfort care; and nurses’ support for patients/families’ spiritual needs). Skew ranged from −1.41 to −1.04, with a larger proportion of responses in the higher response categories for these skewed distributions.

Table 2.

Item distributional characteristics: Nurse and physician respondents

| NURSE RESPONDENTS | PHYSICIAN RESPONDENTS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Valid % | % “0” | % “10” | Skew | N | Valid % | % “0” | % “10” | Skew | |

| Communication Within the Team and with Patients and Families | ||||||||||

| How well do physicians in your ICU communicate with members of the clinical team to clarify goals of care? | 285 | 98.6% | 0.3 | 3.5 | −.449 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.0 | 10.1 | −.524 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU communicate with members of the clinical team to clarify goals of care? | 287 | 99.3% | 0.0 | 12.8 | −.839 | 185 | 98.4% | 0.0 | 9.6 | −.980 |

| How well do physicians in your ICU communicate with patients and families about goals of care and treatment? | 286 | 99.0% | 0.3 | 5.5 | −.558 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.0 | 10.6 | −.486 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU communicate with patients and families about goals of care and treatment? | 287 | 99.3% | 0.0 | 14.2 | −.762 | 184 | 97.9% | 0.0 | 12.8 | −.641 |

| Patient and family centered decision making | ||||||||||

| How well do physicians in your ICU elicit and respect patient’s and/or families preference regarding goals of care and treatment? | 285 | 98.6% | 0.3 | 9.3 | −.576 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.0 | 13.8 | −.745 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU elicit and respect patient’s and/or families preference regarding goals of care and treatment? | 287 | 99.3% | 0.0 | 15.9 | −.618 | 184 | 97.9% | 0.0 | 15.4 | −.858 |

| Continuity of Care | ||||||||||

| How well do physicians in your ICU communicate with colleagues about the patient’s and/or family’s emotional needs? | 282 | 97.6% | 1.7 | 4.5 | −.293 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.0 | 4.8 | −.631 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU communicate with colleagues about the patient’s and/or family’s emotional needs? | 287 | 99.3% | 0.0 | 13.8 | −1.328 | 183 | 97.3% | 0.0 | 10.1 | −1.410 |

| How well do physicians in your ICU communicate the goals of care to the next care givers? | 283 | 97.9% | 2.1 | 7.3 | −.540 | 186 | 98.9% | 0.0 | 6.4 | −1.138 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU communicate the goals of care to the next care givers? | 287 | 99.3% | 0.0 | 18.0 | −.893 | 182 | 96.8% | 0.0 | 13.3 | −.989 |

| Emotional and Practical Support for Patients and Families | ||||||||||

| How well do physicians in your ICU pay attention to emotional and practical needs of dying patients and their families? | 286 | 99.0% | 1.0 | 5.5 | −.321 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.0 | 8.0 | −.716 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU pay attention to emotional and practical needs of dying patients and their families? | 288 | 99.7% | 0.0 | 23.2 | −1.308 | 185 | 98.4% | 0.0 | 17.0 | −.724 |

| Symptom Management and Comfort Care | ||||||||||

| How well do physicians in your ICU manage symptoms and provide comfort care? | 286 | 99.0% | 0.7 | 11.1 | −.734 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.0 | 20.7 | −.424 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU manage symptoms and provide comfort care? | 287 | 99.3% | 0.0 | 27.7 | −1.054 | 185 | 98.4% | 0.0 | 26.1 | −.574 |

| Spiritual Support for Patients and Families | ||||||||||

| How well do physicians in your ICU assess the spiritual/religious needs of the patients and families? | 285 | 98.6% | 4.2 | 2.4 | −.076 | 187 | 99.5% | 0.5 | 5.3 | −.420 |

| How well do nurses in your ICU assess the spiritual/religious needs of the patients and families? | 288 | 99.7% | 0.0 | 15.9 | −1.044 | 183 | 97.3% | 0.0 | 8.5 | −.496 |

| Emotional and Organizational Support for ICU Clinicians | ||||||||||

| How well does your organization support the provision of emotional support for physicians caring for dying patients? | 279 | 96.5% | 8.0 | 0.7 | −.060 | 186 | 98.9% | 3.7 | 2.1 | −.196 |

| How well does your organization support the provision of emotional support for nurses caring for dying patients? | 287 | 99.3% | 2.8 | 6.2 | −.406 | 177 | 94.1% | 1.1 | 2.7 | −.528 |

| How well does your organization support the provision of education about palliative care for physicians? | 277 | 95.8% | 5.9 | 1.7 | −.063 | 186 | 98.9% | 1.1 | 3.2 | −.441 |

| How well does your organization support the provision of education about palliative care for nurses? | 287 | 99.3% | 2.4 | 3.5 | −.403 | 177 | 94.1% | 0.0 | 3.2 | −.759 |

Endorsements of floor scores of “0” ranged from 0% to 3.7% for physician-completed items and from 0% to 8.0% for nurse-completed items. Only two items completed by nurses had more than 5% of scores at the response scales’ floor: “How well does your organization support the provision of emotional support for physicians caring for dying patients?”(8.0%) and “How well does your organization support the provision of education about palliative care for physicians?” (5.9%). Endorsement of ceiling scores of “10” ranged from 2.1% to 26.1% for physician respondents and from 0.7% to 27.7% for nurse respondents. Ceiling scores exceeded 5% on 14 of the 20 items. The item with the highest ceiling scores was “How well do nurses in your ICU manage symptoms and provide comfort care?”(physician respondents = 26.1%; nurse respondents = 27.7%)

Comparison of each item to the symptom management item

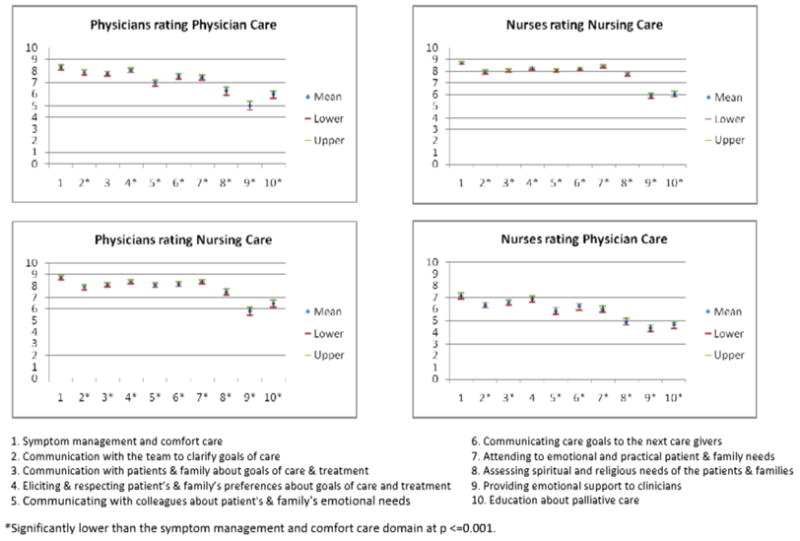

Ratings in each of the ten summary items were all significantly lower than ratings for symptom management, our standard for comparison, with two exceptions: 1) physician ratings of their own ability to communicate goals of care to patients and families; 2) nurse ratings of physicians’ ability to elicit and respect patients’ and families’ preferences about goals of care and treatments. The significantly lower scores in comparison to symptom management persisted regardless of the respondent pattern (i.e., nurses evaluating nursing care; nurses evaluating physician care; physicians evaluating physician care, physicians evaluating nursing care) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ICU clinician ratings of the quality of ICU palliative care comparing the domain of symptom management versus the other six domains of ICU palliative care

Respondents rating care by their own discipline

Respondents in both disciplines (nurses and physicians) rating care provided by their own discipline gave the highest ratings to symptom management (nurse mean = 8.61, physician mean = 8.32) and to eliciting and respecting patients’ and families’ preferences about goals of care and treatment (nurse mean = 8.11, physician mean = 8.05). They gave the lowest ratings regarding care by their own discipline to spiritual support for families (nurse mean = 7.89, physician mean = 6.26), emotional support for clinicians caring for dying patients (nurse mean = 5.95, physician mean = 5.02), and education about palliative care (nurse mean = 5.76, physician mean = 5.97) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nurse and physician ratings within disciplines*

| Nurses rating Nursing Care (n=289) | Physicians rating Physician Care (n=188) | Effect Size: Cohen’s d | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | ||||

| Domain 1: | Symptom management and comfort care | 8.61 (1.28) | 8.32 (1.28) | 0.23 | 0.007 |

| Domain 2a: | Communication about goals of care: within the team | 7.96 (1.45) | 7.87 (1.33) | 0.06 | 0.392 |

| Domain 2b: | Communication about goals of care: with patients and families | 8.02 (1.42) | 7.78 (1.38) | 0.17 | 0.046 |

| Domain 3: | Patient- and family-centered decision-making | 8.11 (1.33) | 8.05 (1.39) | 0.04 | 0.472 |

| Domain 4a: | Continuity of care: with colleagues | 8.04 (1.51) | 6.96 (1.78) | 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Domain 4b: | Continuity of care: with caregivers | 8.25 (1.35) | 7.53 (1.58) | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Domain 5: | Emotional and practical support for patients and families | 8.43 (1.41) | 7.43 (1.61) | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Domain 6: | Spiritual support for patients and families | 7.89 (1.71) | 6.26 (2.14) | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Domain 7a: | Emotional and organizational support to ICU clinicians; emotional | 5.95 (2.63) | 5.02 (2.47) | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Domain 7b: | Emotional and organizational support to ICU clinicians; educational | 5.76 (2.53) | 5.97 (2.15) | 0.09 | 0.413 |

p values based on robust regression analyses controlling for site

Nurses rating nurses compared to physicians rating physicians

Nurses’ ratings of care by nurses were significantly higher than physicians’ ratings of care by physicians on 5 of the 10 items (p <0.001): continuity of care with colleagues, continuity of care with the next caregivers, emotional and practical support for the patient and family, spiritual support for the patient and family, and emotional support for clinicians Effect sizes for these significant differences ranged from 0.36 to 0.84, qualifying as small (0.20), medium (0.50) and large (0.80) effects using Cohen d 31 (Table 3).

Ratings of own compared to rating of other discipline

Nurses’ ratings of physician care were significantly lower than physicians’ ratings of physician care at p < 0.001 on all except one item (provision of emotional support for clinicians caring for dying patients, p = 0.009; Table 4). Effect sizes were moderate to large, ranging from 0.54 to 0.92. In contrast, nursing care was rated similarly by both nurses and physicians (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nurse and physician ratings within and across disciplines*

| Ratings of Physician Care | Ratings of Nursing Care | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses’ Ratings (n=289) | Physicians’ Ratings (n =188) | Effect Size: Cohen’s d | P1 | Nurses’ Ratings (n=289) | Physicians’ Ratings (n =188) | Effect Size: Cohen’s d | P2 | ||

| Domain 1: | Symptom management and comfort care | 7.12 (2.07) | 8.32 (1.28) | 0.70 | <0.001 | 8.61 (1.28) | 8.75 (1.04) | 0.12 | 0.259 |

| Domain 2a: | Communication about goals of care: within the team | 6.33 (1.96) | 7.87 (1.33) | 0.92 | <0.001 | 7.96 (1.45) | 7.91 (1.41) | 0.03 | 0.822 |

| Domain 2b: | Communication about goals of care: with patients and families | 6.54 (2.02) | 7.78 (1.38) | 0.72 | <0.001 | 8.02 (1.42) | 8.10 (1.29) | 0.06 | 0.439 |

| Domain 3: | Patient- and family- centered decision-making | 6.85 (2.09) | 8.05 (1.39) | 0.68 | <0.001 | 8.11 (1.33) | 8.35 (1.21) | 0.19 | 0.072 |

| Domain 4a: | Continuity of care: with colleagues | 5.82 (2.40) | 6.96 (1.78) | 0.54 | <0.001 | 8.04 (1.51) | 8.09 (1.39) | 0.03 | 0.636 |

| Domain 4b: | Continuity of care: with caregivers | 6.20 (2.38) | 7.53 (1.58) | 0.66 | <0.001 | 8.25 (1.35) | 8.17 (1.35) | 0.06 | 0.641 |

| Domain 5: | Emotional and practical support for patients and families | 5.99 (2.36) | 7.43 (1.61) | 0.71 | <0.001 | 8.43 (1.41) | 8.38 (1.22) | 0.04 | 0.696 |

| Domain 6: | Spiritual support for patients and families | 4.91 (2.53) | 6.26 (2.14) | 0.58 | <0.001 | 7.89 (1.71) | 7.47 (1.68) | 0.25 | 0.004 |

| Domain 7a: | Emotional and organizational support to ICU clinicians; emotional | 4.33 (2.55) | 5.02 (2.47) | 0.28 | 0.009 | 5.95 (2.63) | 5.84 (2.48) | 0.04 | 0.517 |

| Domain 7b: | Emotional and organizational support to ICU clinicians; educational | 4.63 (2.57) | 5.97 (2.15) | 0.57 | <0.001 | 5.76 (2.53) | 6.49 (2.03) | 0.32 | 0.002 |

p values based on robust regression analyses controlling for site

P values compare nurses’ ratings of physician care with physician ratings of physician care.

P values compare nurses’ ratings of nurse care with physician ratings of nurse care.

Ratings of house staff compared to attending physicians

House staff rated physician care significantly higher only on the patient and family centered decision making item and the effect size was moderate (0.52). We found trends toward higher ratings by house staff (at a p value < 0.05, but > 0.001) for six additional items (Table 5).

Table 5.

Attending and Housestaff ratings of physician care

| Attendings’ Ratings (n=83) | House staff’s Ratings (n=104) | Effect Size: Cohen’s d | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: | Symptom management and comfort care | 8.14 (1.33) | 8.48 (1.22) | 0.27 | 0.020 |

| Domain 2a: | Communication about goals of care: within the team | 7.72 (1.34) | 7.99 (1.33) | 0.20 | 0.225 |

| Domain 2b: | Communication about goals of care: with patients and families | 7.53 (1.55) | 7.99 (1.21) | 0.33 | 0.036 |

| Domain 3: | Patient- and family-centered decision-making | 7.66 (1.60) | 8.38 (1.10) | 0.52 | 0.001 |

| Domain 4a: | Continuity of care: with colleagues | 6.65 (1.90) | 7.21 (1.64) | 0.32 | 0.189 |

| Domain 4b: | Continuity of care: with caregivers | 7.12 (1.85) | 7.83 (1.26) | 0.45 | 0.017 |

| Domain 5: | Emotional and practical support for patients and families | 7.22 (1.75) | 7.62 (1.46) | 0.25 | 0.030 |

| Domain 6: | Spiritual support for patients and families | 6.05 (2.23) | 6.45 (2.06) | 0.19 | 0.184 |

| Domain 7a: | Emotional and organizational support to ICU clinicians; emotional | 4.60 (2.53) | 5.34 (2.37) | 0.30 | 0.043 |

| Domain 7b: | Emotional and organizational support to ICU clinicians; educational | 5.34 (2.25) | 6.47 (1.95) | 0.54 | 0.005 |

p values based on robust regression analyses controlling for site

Discussion

We had two primary goals in this study: 1) to evaluate the content validity of the 10 overall rating items assessing 7 domains central to the delivery of palliative care; and 2) to use these 10 overall rating items to assess the quality of palliative care delivered in the ICU as rated by clinicians working in the ICU. In our analyses of item measurement characteristics, we found the rating items met most of the criteria that support the appropriateness definition associated with content validity: few missing responses, little skew, and minimal floor effects. The one critieria that was unmet was the percent of ceiling scores. Seventy percent of items (14/20) had ceiling scores greater than 5% and 45% of items (9/20) had ceiling scores greater than 10%. While ceiling scores limit the items’ ability to demonstrate additional quality improvement, they are unlikely to undermine the appropriateness of the items to provide a measure of the current quality of palliative care.

In our analyses comparing aspects of palliative care to the domain of symptom management, we found opportunities for improvement. All domains except one were rated as significantly lower than the domain of symptom management. We noted that three domains in particular received relatively lower ratings: the provision of education about palliative care to clinicians, the assessment of spiritual and religious needs of the patient and family, and the provision of emotional support for clinicians caring for dying patients.

Previous research has also supported a need for improvement in these domains. The low rating for ICU clinician education in palliative care is consistent with the Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care which noted a lack of training in end-of-life care for ICU clinicians.32 Spiritual support is an important and under-achieved aspect of comprehensive care in the ICU, and the assessment of spiritual and religious needs of patients and families are important first steps in being able to provide spiritual support.33, 34 Additionally, spiritual and religious needs’ assessments of patients and families are important because family satisfaction with spiritual care is an important predictor of family satisfaction with their overall ICU care.33 The low ratings in the domain of emotional support for clinicians are concerning since caring for dying patients is a strong risk factor for burnout,35 and poor support may lead to higher levels of burnout. Addressing emotional support for ICU clinicians may be an important step in ensuring an adequate critical care workforce in the future.36, 25 Ratings of this domain are especially meaningful as clinicians are in the best position to evaluate it, as opposed to other domains that might be better evaluated by patients or families.37

We also found that palliative care delivered by nurses as rated by nurses was significantly higher than physician care rated by physicians. These higher ratings for nurses may be due to the fact that ICU nurses are the clinicians that spend the most time at the bedside. They therefore play important roles supporting patients and families in the domains identified here.38–40 Higher ratings for nurses are supported by surveys of clinician barriers to high quality palliative in the ICU documenting that physicians experience more barriers than nurses, especially in the areas of clinician training in communication and palliative care.41

Interestingly, nurse delivery of palliative care was rated similarly regardless of rater but physician delivery of palliative care was rated significantly differently depending on rater. Physicians consistently rated physician care higher than did nurses rating physician care. This discrepancy between raters for physician care suggests the need for improved communication among clinicians providing palliative care in the ICU.42, 43 Several studies suggest that current interdisciplinary collaboration about end-of-life care in the ICU is variable and often poor. For example, a study from France showed that collaboration about end-of-life decision-making between physicians and nurses occurred only 27% of the time as reported by nurses and 50% as reported by physicians.44 A more recent study from Europe found that physicians reported that nurses were involved in end-of-life decisions in three-quarters of cases involving withholding or withdrawing life support, but there was significant variability between northern and southern Europe.45 A transcontinental study of physicians found wide regional variability in the proportion of decisions about end-of-life care in the ICU in which physicians reported involving nurses with the U.S. reporting the lowest proportion of all countries studied.34 Furthermore, most of the interventions that have resulted in improvements of end-of-life care in the ICU have involved interdisciplinary teams in the interventions.4–7 Interventions that facilitate and support communication and collaboration within the context of an interdisciplinary approach may result in more concordant evaluations of, and improvements in, ICU palliative care.

In our analysis comparing house staff and attending ratings, we found that house staff rated one item significantly higher (at our stringent p value of 0.001): patient- and family-centered decision making. In addition, there were trends for higher ratings by housestaff on six other items. These findings are in contrast to an earlier study that showed that house staff rated the quality of dying for patients in the ICU significantly lower than attending physicians.19 It is difficult to reconcile these findings. It may be that house staff are exposed to more training about communication and emotional support and perceive these components of care as better than attendings while rating the overall dying experience as worse. Further study is needed to understand these differences.

A unique component of this study is the use of clinician ratings. Clinician ratings are not only more easily accessible than those of patients and families but, because clinicians take care of critically ill patients on a daily basis, they may be able to use their previous experiences to gauge the current delivery of palliative care. Since differences in ratings identify differences in perceptions of quality of palliative care, these ratings may also be useful to help target improvements in care that could help improve shared perceptions and mitigate conflict among ICU clinicians and between disciplines. This is important because prior research has shown that conflict among clinicians in the ICU about end-of-life care is common and harmful to patient care and clinician well-being.35, 46–48 In addition, research from outside the ICU setting suggests that improved interdisciplinary collaboration has a high likelihood of improving quality of palliative care.49, 50, 51 Finally, clinicians’ ratings may lead to interventions that are more likely to succeed in improving care because they are directed to resolving problems that are recognized and endorsed by clinicians.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the participating sites and the ICU clinicians who completed questionnaires volunteered for this study and therefore constituted a convenience sample that may not be representative of all ICU clinicians or hospital sites. We were unable to determine the denominator of eligible clinicians and therefore cannot calculate an accurate response rate. Therefore, our ability to generalize these findings broadly is limited. However, because we obtained responses from an interdisciplinary sample of nearly 500 ICU clinicians representing 13 institutions with diverse characteristics across the country, this study provides insight into the specific centers sampled and the items used to rate quality of palliative care. Second, in an effort to ensure anonymity in this initial use of these items, we collected very little demographic or professional characteristics about the clinicians surveyed and cannot assess whether these characteristics are associated with ratings of palliative care. Third, our findings are drawn from a novel set of items that needs to be studied further in order to understand its psychometric properties, including reliability, validity and responsiveness. Our data provide a first step in that process and our findings should be considered as exploratory. Finally, our approach of using symptom management as the “standard” is supported by some literature,2, 26–28 but also somewhat arbitrary and other standards could have been used.

In summary, our study suggests that, as perceived by the ICU clinicians, there are domains in which ICU palliative care needs targeted improvement including spiritual support for families, emotional support for clinicians, and clinician education about palliative care in the ICU. Further, there are significant differences between how nurses and physicians rate each others’ palliative care skills in the ICU with physicians’ care being rated more poorly than nurses’ care in this area. Our findings also support the importance of interdisciplinary communication and collaboration as an avenue to improve palliative care in the ICU. Finally, this study provides preliminary evidence supporting further evaluation of survey items assessing the quality of palliative care in the ICU as rated by physicians and nurses in that ICU.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by an R01 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (RO1-NR-05226) and a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Dr. Curtis received funding from NIH grants. Dr. Engelberg received funding from NIH. Dr. Levy received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. All other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American Academy of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–63. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;177(8):912–27. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123(1):266–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1530–5. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Measuring success of interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S341–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237048.30032.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2255–62. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S404–11. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson JE, Meier D, Oei EJ, et al. Self-reported symptom experience of critically ill cancer patients receiving intensive care. Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29:277–82. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radwany S, Albanese T, Clough L, Sims L, Mason H, Jahangiri S. End-of-Life Decision Making and Emotional Burden: Placing Family Meetings in Context. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2009;26(5):376–83. doi: 10.1177/1049909109338515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynn J, Teno L, Phillips R. Perception of family members of the dying experience of older and serious ill patients. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(2):97–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-2-199701150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerstel E, Engelberg RA, Koepsell T, Curtis JR. Duration of withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit and association with family satisfaction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(8):798–804. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1617OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whipple JK, Lewis KS, Quebbeman EJ, et al. Analysis of pain management in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy. 1995;15:592–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1995.tb02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addington-Hall J, McPherson C. After-death interviews with surrogates/bereaved family members: some issues of validity. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2001;22(3):784–90. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, Curtis JR. Potential for Response Bias in Family Surveys About End-of-Life Care in the ICU. Chest. 2009;136(6):1496–502. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(7):1413–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Quality of dying and death in two medical ICUs: perceptions of family and clinicians. Chest. 2005;127(5):1775–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirchhoff KT, Anumandla PR, Foth KT, Lues SN, Gilbertson-White SH. Documentation on withdrawal of life support in adult patients in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2004;13(4):328–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, Pronovost PJ. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: a practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(4):264–71. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178(3):269–75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodde NM, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR. Factors associated with nurse assessment of the quality of dying and death in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1648–53. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133018.60866.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon SE, Mitchell PH, Cain K. Patients, nurses and physician have different views of quality of critical care. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002 doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00173.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):422–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254722.50608.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mularski RA, Puntillo K, Varkey B, et al. Pain Management Within the Palliative and End-of-Life Care Experience in the ICU. Chest. 2009;135(5):1360–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mularski RA. Pain management in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(3):381–401. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perrin EB, Aronson NK, Alonso J, et al. Instrument review criteria. Medical Outcomes Trust Bulletin. 1995;3:I–IV. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU. Intensive Care Med; Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care; Brussels, Belgium. April 2003; 2004. pp. 770–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, Glavan B, Curtis JR. Spiritual care of families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1084–90. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259382.36414.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yaguchi A, Truog RD, Curtis JR, et al. International Differences in End-of-Life Attitudes in the Intensive Care Unit: Results of a Survey. Archives of internal medicine. 2005;165(17):1970–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175(7):698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JR, Puntillo K. Is there an epidemic of burnout and post-traumatic stress in critical care clinicians? American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175(7):634–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-194ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espinosa L, Young A, Symes L, Haile B, Walsh T. ICU nurses’ experiences in providing terminal care. Critical care nursing quarterly. 33(3):273–81. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3181d91424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirchhoff KT, Conradt KL, Anumandla PR. ICU nurses’ preparation of families for death of patients following withdrawal of ventilator support. Appl Nurs Res. 2003;16(2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(03)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamerson PA, Scheibmeir M, Bott MJ, Crighton F, Hinton RH, Cobb AK. The experiences of families with a relative in the intensive care unit. Heart and Lung. 1996;25(6):467–74. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(96)80049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClement SE, Desgner LF. Expert nursing behaviors in care of the dying adult in the intensive care unit. Heart and Lung. 1995;24(5):408–19. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld LA, et al. End-of-life care for the critically ill: A national intensive care unit survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2547–53. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtis JR, Shannon SE. Transcending the silos: toward an interdisciplinary approach to end-of-life care in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(1):15–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Mahony S, McHenry J, Blank AE, et al. Preliminary report of the integration of a palliative care team into an intensive care unit. Palliative medicine. 2009;24(2):154–65. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B, et al. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2003;167(10):1310–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-752OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benbenishty J, Ganz FD, Lippert A, et al. Nurse involvement in end-of-life decision making: the ETHICUS study. Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32(1):129–32. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Burns JP, et al. Conflict in the care of patients with prolonged stay in the ICU: types, sources, and predictors. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(9):1489–97. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180(9):853–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1614OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175(7):686–92. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinke LF, Shannon SE, Engelberg R, Dotolo D, Silvestri GA, Curtis JR. Nurses’ identification of important yet under-utilized end-of-life care skills for patients with life-limiting or terminal illnesses. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010;13(6):753–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinke LF, Shannon SE, Engelberg RA, Young JP, Curtis JR. Supporting hope and prognostic information: nurses’ perspectives on their role when patients have life-limiting prognoses. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;39(6):982–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S, Horton D. Medical decision-making in the nursing home: a comparison of physician and nurse perspectives. Journal of gerontological nursing. 2006;32(12):14–21. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20061201-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]