Abstract

Underrepresentation of HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans in clinical trials seriously limits our understanding of the benefits and risks of treatment in these populations. This qualitative study examined factors that racial/ethnic minority patients consider when making decisions regarding research participation. Thirty-five HIV-infected Hispanic and African American patients enrolled in clinical research protocols at the National Institutes of Health were recruited to participate in focus groups and in-depth interviews. The sample of mostly men (n = 22), had a mean age of 45, nearly equal representation of race/ethnicity, and diagnosed 2 to 22 years ago. Baseline questionnaires included demographics and measures of social support and acculturation. Interviewers had similar racial/ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds as the participants. Four major themes around participants’ decisions to enroll in clinical trials emerged: Enhancers, Barriers, Beliefs, and Psychosocial Context. Results may help researchers develop strategies to facilitate inclusion of HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans into clinical trials.

Keywords: African American/Black, clinical research, decision-making, health disparities, Hispanic/Latino, HIV

The realities of health disparities are well documented (Caban, 1995; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2009), the HIV epidemic is a health crisis for African Americans and a serious threat to the Hispanic community. Because HIV disproportionately affects Hispanics and African Americans in the United States, it is imperative that they are adequately represented in HIV-related research. In 2007, African Americans accounted for 51% (42,655) of the new HIV cases and 44% of the 455,636 estimated AIDS cases in the United States (CDC, 2010), while making up only about 13.5% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). As of July 2008, Hispanics accounted for 15% of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009), yet according to the CDC (2009), Hispanics accounted for 18% of the new cases of HIV. The purpose of this exploratory study was to examine the decision-making processes of HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans about enrolling in clinical research.

Background and Significance

Minority underrepresentation in clinical trials is of significant concern because it prohibits generalizability of results (Stone, Mauch, Steger, Janas, & Craven, 1997; Wendler et al., 2006). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services identified the underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities and women in clinical research as a major issue (Caban, 1995), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has required inclusion of women and minorities with a plan for outreach and recruitment in all clinical trials (NIH, 2001). Murthy, Krumholz, and Gross (2004) analyzed the National Cancer Institute-sponsored Clinical Trial Group therapeutic trials from 2000–2002 and found that, over the 10-year period since Congress mandated inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities and women in clinical trials, racial/ethnic minorities continued to be underrepresented. The researchers suggested designing studies specifically for racial/ethnic groups that experience a higher incidence of disease. Their work focused on cancer, but the same recommendation could be applied to many other diseases including HIV.

Wright et al. (2004) developed a questionnaire to identify the factors associated with enrolling in a clinical trial. The questionnaire was pilot tested using focus groups and then administered to 189 patients, physicians, and clinical research associates. This study did not include race/ethnicity data. Overall, 7% of the patients thought they should make their own decision about enrolling in a clinical trial, 5% thought the doctor should make the decision, 20% thought the doctor should make the decision with patient input, 36% thought the doctor and patient should make the decision together, and 33% thought the patient should make the decision and ask for the doctor’s opinion.

Data from the HIV Cost and Service Utilization Study (Gifford et al., 2002) demonstrated that neither trust nor involvement in decision-making were independently associated with participation in a clinical trial. Racial/ethnic underrepresentation also existed in this study. Shedlin, Decena, and Oliver-Velez (2005) studied acculturation among new immigrants and found that language was a key obstacle in their lives. Therefore, in the case of Hispanics, eliminating language and cultural barriers could increase participation in clinical trials (Allen et al., 2001).

Several reasons have been documented for the underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials, including mistrust, not being informed about clinical trials, language barriers, fear of experimentation or of being guinea pigs, and conspiracy theories (Cargill & Stone, 2005; Corbie-Smith, Thomas, Williams, & Moody-Ayers, 1999; Newman, Duan, Rudy, & Anton, 2004; Stone et al., 1997; Wendler et al., 2006). In the majority of studies that investigated trust, the Tuskegee study played a significant role in the decision of African Americans not to participate in a study. The Tuskegee study is well known for impacting the relationship between African Americans and medical research but it is not the only source of this distrust. Although particular historical events have less direct influence on trust for other ethnic groups, racial discrimination is still an issue influencing willingness to participate (Powe & Gary, 2004). A study by Ross, Essien, and Torres (2006) found that Hispanics also believed in a conspiracy theory based on their own experiences with racism. For both Hispanics and African Americans, family played a key role in the participant’s decision not to enroll in a clinical trial (Ellington, Wahab, Sahami, Field, & Mooney, 2003). A comprehensive literature search by Wendler et al. (2006) found that lack of access to research accounted for minority underrepresentation, not that racial/ethnic minorities were less willing than non-minorities to participate in medical research.

There is limited research on how HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans decide to participate in clinical trials. Mueller (2004) used face-to-face interviews to explore how patients with HIV gave consent to enroll into a clinical trial and identified three contingencies (clinical, social, and technical) that patients used in deciding to enroll in a clinical trial. Clinical contingency occurs because of the uncertainties a patient experiences during illness. Helping others (altruism) is the force behind social contingency. Technical contingency is the value that the patient places on the clinical trial.

The objective of this study was to examine the factors HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans use when making decisions about enrolling in a clinical trial. Specifically, this study aimed to identify enhancers, barriers, and beliefs as they pertain to decision-making for HIV clinical trials participation. Qualitative research methods were selected because they provide the insight required to develop hypotheses to understand and model phenomena for testing in larger samples and to develop interventions to improve representation of minorities in clinical trials.

Method

Design

This was a qualitative study designed to examine the decision-making process among a purposive sample of minority patients who were enrolled in an active National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) HIV clinical trial. This study was intentionally conducted with racial/ethnic minorities currently participating in clinical research at NIH in order to gain insight into what influenced their decisions to enroll. The specific qualitative data collection procedures used were focus groups and in-depth interviews. By design, this exploratory study conducted one focus group for each gender and racial/ethnic-specific subgroup. An iterative process designed to identify common themes across individuals and focus groups will be discussed in the analysis section.

Sample

Study inclusion criteria required that participants were involved in some form of active treatment, which could be a placebo-controlled trial or an active-comparison trial with or without randomization. Participation solely in a natural history study, which is a study that does not offer intervention or treatment but follows the natural progression of the disease, was an exclusion criterion.

Procedures

The NIAID Institutional Review Board approved this study. Before data collection began, the patient signed a written consent document describing the purpose and activities of the study and was provided with a copy of the consent form. The statement that withdrawal from the study would not affect the health care subsequently received was included in the consent document. For their time, participants received remuneration in the amount of $50 for each phase.

The study design included two phases: focus groups and in-depth interviews. Participants had the option of participating in (a) a focus group, (b) an in-depth interview, or (c) both. Focus groups were conducted in a facility that specialized in focus groups located close to the NIH campus. In-depth interviews were conducted on the NIH campus.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete the following forms: demographic, acculturation scale (Hispanics only), and social support. Each participant was given the option to independently fill out the questionnaire or to receive assistance from a research team member. The surveys included demographics and clinical characteristics, a two-item measure social support, and a four-item Short Acculturation Scale (SAS). The SAS was adapted from Marin Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, and Perez-Stable (1987), validated by Wallen, Feldman, and Anliker (2002) and administered to Hispanic/Latino participants to document their language preferences as a proxy measure for acculturation. Values ranging from 1 (respondent speaks Spanish 100% of the time) to 5 (respondent speaks English 100% of the time) were assigned to each of the four acculturation items. Scores for each item were summed to create an acculturation scale with possible scores ranging from 4 to 20. The higher the combined score, the more acculturated the respondent. The mean for the acculturation scale was 2.3, indicating a low acculturation score. The data suggest that the longer the participant was in the United States, the more acculturated s/he became (0.64, p < 0.01). Also the higher the acculturation score the longer s/he had been diagnosed. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency in this study was 0.91.

In this study, trust was not directly explored, that is, participants were not asked specifically about trust issues. However, the focus group moderator and the interviewer for the in-depth interviews were provided with probes in the event that a participant raised the issue.

Focus group

A research contractor assisted with scheduling focus groups, finding a focus group site within the community setting, and data collection. Two moderators (the principal investigator [PI] and a research contractor) and at least one facilitator led each focus group; groups lasted 2 hours and were conducted at an offsite location. A moderator led the discussion with a Moderator’s Guide that included pre-selected questions and probes. The questions were grouped in categories recommended by Krueger (1998a): opening; introductory, transition, key, and closing. The facilitator took notes, made observations and managed the equipment (tape recorder, microphones, etc.). After the focus group ended, the participants were given pizza. Using the principles of racial/ethnic concordance (Saha, Komaromy, Koepsell, & Bindman, 1999), moderators and facilitators with similar racial/ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds as the participants were selected and trained to conduct the focus groups. This selection of moderators was essential to facilitate communication and identify cultural nuances.

A total of four focus groups with HIV-infected patients were conducted over a period of 30 days. English-speakers were defined as participants who spoke English 75–100% of the time. Spanish-speakers self-identified as speaking Spanish 75–100% of the time. Participants who spoke both Spanish and English were asked which language focus group they preferred. In the focus groups with Hispanics, the participants frequently switched language of preference between English and Spanish. If participants indicated a desire to participate in an in-depth interview, they were able to do so.

The focus group moderator’s guide was developed to answer research questions and was divided into two main sections called Process and Questions (Wallen & Rivera-Goba, 2003). The Process Section, or setting the stage, was composed of three parts: introduction of everyone present, description of the focus group purpose, and helpful hints for running the focus group. The Questions Section, or data collection, included four sub-sections. In the first section, Introductory Questions asked participants to share something about themselves that made them proud. In the second section, a Transition Activity consisting of a warm-up exercise, also known as an ice-breaker, invited participants to create a collage that reminded them of someone in the community that was infected with HIV. The purpose of these two sections was to make the participants feel comfortable and to have them begin to think about people in the community (Wallen & Rivera-Goba, 2003). In the third section, the Key Questions explored the concept of decision-making. Examples of questions asked in this section included, “What influenced your decision to participate in a research study?” (Probe, “What would make you decide to participate in a research study?”) and “What are some important issues we should be aware of regarding how Hispanics/African Americans decide whether or not to participate in research?” In the final section, the Closing Question, participants were asked for input about what they would do differently if they were conducting this study.

In-depth interview

Twenty-four in-depth interviews were conducted (12 with African American/Blacks and 12 with Hispanics/Latinos). The interviews were semi-structured and consisted of open-ended questions. The interviewer was matched to the race/ethnicity of the patient (concordance) and a bilingual researcher conducted the Spanish-language interviews. Participants who completed an in-depth interview and expressed interest in participating in a focus group were allowed to do so.

The in-depth interview guide consisted of questions that had a specific focus around issues related to illness/condition, experiences with health care prior to enrolling in a research study, and present experiences. Participants were asked questions like, “Walk me through your thoughts and experiences as you made the decision to participate in a clinical trial,” were asked about influences that would foster or hinder participation in research, and were encouraged to share anything not already discussed about the research experience. A linguist with expertise in scientific terminology translated all written materials into Spanish.

Data Collection

The study was open to all HIV-infected patients participating in an appropriate study at NIH. Most of the patients were recruited from an outpatient specialty research clinic. Three recruitment mechanisms were used to enroll potential participants. First, nurses from the outpatient specialty clinic reviewed the list of patients returning to the clinic in 2 weeks for follow-up visits and identified potential participants. When contacting the patient about the upcoming appointment, the nurses introduced the study. If the patient expressed interest, the nurse provided him/her with the name and contact information of the PI. A second approach consisted of English- and Spanish-language posters advertising the study and posted at NIH-approved locations near the clinics, metro (train stations), and elevators. Third, the PI and/or an associate investigator were available during clinic hours to speak with patients directly. Once patients expressed interest in participating in the study, they were informed of study details and a consent form was provided in English or Spanish, based on the patient’s language preference.

Data Analysis

According to Cohen, Kahn, and Steeves (2000), data analysis is not a separate step after the data have been collected. Rather, analysis begins during interviews when researchers are actively involved in listening and thinking about the meanings of what participants say. This leads to a more careful analysis in which transcripts are thoroughly read as the researcher becomes increasingly immersed in the data. Cohen et al. (2000) also describe a three-phase approach to data analysis. In the first phase, essential characteristics from the data are identified. This is the coding of the data. In the second phase, data are transformed or reduced. Here, the researcher has to decide which data are significant and which are not. The third phase is thematic analysis. This is the phase where the researcher sees themes begin to emerge. Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns within each group, determining similarities and differences across groups. At this point, the qualitative computer software (NVivo) was used as an additional tool to index and continue narrowing the themes. Quantitative data analysis is descriptive and exploratory in nature to describe the study sample.

Content analysis was used for the qualitative data. Transcript-based analysis of the data is considered to be the most rigorous choice for analyzing information generated during focus groups (Krueger, 1998b). Field notes taken by the facilitator during focus groups and debriefing sessions with the moderators and facilitators were also examined. All audio-recorded tapes were transcribed verbatim by independent, trained consultants. Interviews conducted in Spanish were first transcribed in Spanish and then translated into English. After each transcript was completed, the members of the research team conducted a secondary review of the audiotapes and transcripts to check for accuracy using guidelines provided by the PI. The analysis plan consisted of identifying the four following steps: general ideas, choice and meaning of the words, context, and consistency of responses. For this study, three themes were pre-specified: enhancers, barriers, and beliefs. The PI and three other team members conducted the data analysis. Transcripts from in-depth interview and focus groups were read several times. Initial review was for understanding content followed by identifying patterns and then developing the subthemes. Those responsible for analysis first conducted independent reviews and then the team met to discuss the identified patterns. This process continued until the final subthemes emerged.

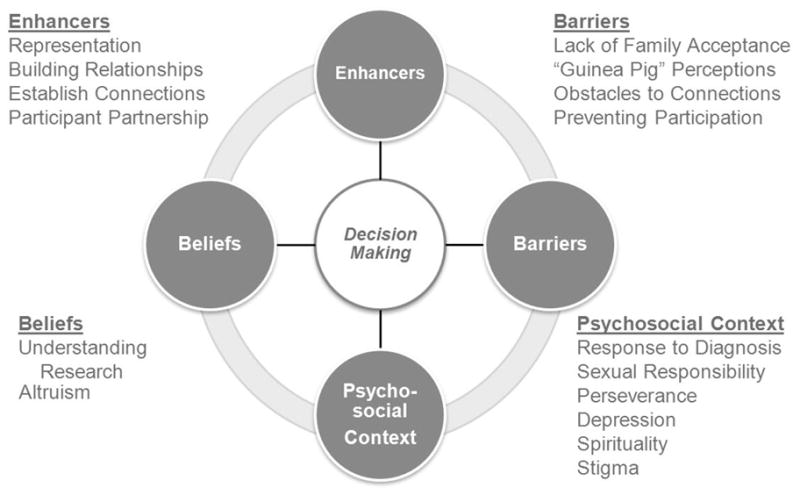

Enhancers are the factors that determine if the participant will enroll in a clinical trial. The more enhancers (positive factors) present, the more likely the person will participate in research. Participants provided specifics as to what would increase the likelihood of participation. Barriers are those factors that would prevent or keep an individual from participating in research. Beliefs are the ideas and viewpoints that the participant held that influenced their decisions.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total sample of 35 participants (24 in-depth interviews and 21 focus group members with 9 participants who participated in both) completed the study. The study sample was predominantly male (62.9%), had a mean age of 45 years (SD = 10), and was almost equally divided in terms of race/ethnicity (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| Characteristics | Total sample (N = 35) | In-depth Interview (n= 24) | Focus Group (n = 21) | In-depth Interview and Focus Group (n = 9) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||||||

| < 40 | 10 | 28.6 | 7 | 29.2 | 5 | 23.8 | 3 | 25.0 |

| 40–55 | 19 | 54.3 | 15 | 62.5 | 12 | 57.1 | 7 | 58.3 |

| > 55 | 6 | 17.1 | 2 | 8.3 | 4 | 19.0 | 2 | 16.7 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 13 | 37.1 | 9 | 37.5 | 9 | 42.9 | 5 | 41.7 |

| Male | 22 | 62.9 | 15 | 62.5 | 12 | 57.1 | 7 | 58.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 17 | 48.6 | 12 | 50 | 7 | 33.3 | 5 | 41.7 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 18 | 51.4 | 12 | 50 | 14 | 66.7 | 7 | 58.3 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 8 | 22.9 | 5 | 20.8 | 3 | 14.3 | 3 | 25.0 |

| Black/African American | 19 | 54.3 | 12 | 50 | 14 | 66.7 | 7 | 58.3 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| More than one race | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 16.7 | 4 | 19.0 | 2 | 16.7 |

| Unknown/Not reported | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

A total of four gender and racial/ethnic specific focus groups were conducted: The first focus group consisted of seven African American males, the second consisted of seven African American females, the third consisted of two Hispanic females (although we would have liked to have had a larger focus group, the researchers felt committed to acknowledging the participants’ time and commitment to the study and decided not to cancel this focus group), and the fourth consisted of five Hispanic males. In total, 21 study participants attended focus groups. The two focus groups with Hispanics were conducted in Spanish.

All Hispanic participants, regardless of country of origin, spoke Spanish to some degree. None of the Hispanic participants felt most comfortable speaking English only, although some had been in the United States all their lives. The participants represented seven Hispanic countries and no demographic differences were observed by ethnic sub-group.

Themes

The objective of this study was to understand participants’ perceptions around the three main themes of enhancers, barriers, and beliefs as they related to decision-making. This objective was directly related to understanding the decision-making process of enrolling in clinical research. The data provided themes under these categories as well as identified a fourth theme, psychosocial context, which emerged from the data (as shown in Figure 1). Examples of the participants’ quotes around the four main themes are provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing minority decision-making in HIV clinical trials.

Table 2.

Participant Perceptions

| Themes | Exemplars |

|---|---|

| Enhancers | Well because there’s not enough African Americans period in studies…. I’m [not] going to just hold to that Tuskegee thing, I just think we’re ignorant to a lot of things. (Representation) The kindness and the certainty with which they speak, the assurance with which they speak, and that they don’t see you as a victim, that they don’t see you as, “oh, poor thing, she is here,” but rather they look at you face-to-face, without, well, without making you feel like a trapped animal, at least that’s what I think. (Building Relationships) You know actually, when I first came here, I thought I was gonna be dealing with, you know all these…crazy scientists…I think there’s like a comfort level here. There’s like a welcome. (Establishing Connection) I just wanted to make a mark in this world because this is such an epidemic, the HIV and the AIDS. I would like to leave my mark on the HIV and AIDS virus as a fighter against this thing even if my name never shows up in any magazine or any book. It’s not the front of the scene; it’s what’s happening behind the scenes. I felt compelled to be a part of the cure or at least the control factor of these things. (Participant Partnership) |

| Barriers | She [mother] didn’t have the knowledge of how she could catch it and all this stuff. She wasn’t reading on it and every time he [brother] touched something she used to wipe it off. She used to bleach the toilet. She was scared to touch him. (Lack of Family Acceptance) If I had a client who was African American, she knew about Tuskegee…. If I had a client that was from Latin America, it was because of the fact that in those countries, you don’t trust the government. You don’t trust the government. And I think that’s basically the biggest thing with minority groups. So at one time, I didn’t trust the government. Not that I trust it now. (“Guinea Pig” Perceptions) As soon as the conversation started, you know, I think you can tell. You know, by the way the person talks to you, the way they, you know, whether it be body language, or what comes out of their mouth, you know, the way they look at you. You know different things. (Obstacles to Connection) The medication is…is one factor. The invasiveness of the study is another factor. (Preventing Participation) |

| Beliefs | Not just for me, speaking in terms of things outside of me, it is also to help many others that do not have the opportunity I have to be in this study or who are afraid to be in this study. (Altruism) I think the biggest right is the fact that you know you don’t have to participate and that you can choose to remove yourself from it at whatever time you want. (Understanding Research) |

| Psychosocial Context | Ummm, my life has changed since that moment [when diagnosed with HIV] and it has been for the better. I have never blamed myself of anything or regretted anything. Since I knew that I was HIV positive for me it was like a turn of life (like the tables turned), from one view of life to another. I never experienced any emotional problems. On the contrary I felt more secure in myself. I gave thanks to God for life and for giving me an opportunity because life does not end there. On the contrary, it was the moment to say, “I can and have to continue on.” (Response to Diagnosis) But it wouldn’t have crossed my mind. I knew that it was in my hands, you REALLY, REALLY, know that I could actually put somebody in the situation that I was in. I decided I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want to do that. (Sexual Responsibility) I was enabled through the volunteer experience to actually see people that were continuing to lead, live, you know, successful lives and … it wasn’t necessarily a death sentence that once it had been. (Perseverance) …because I was very, very depressed. I had a lot of anxiety. I wanted so much not to know, not to know about HIV to refuse being a mother, refuse to live in that way that, even though here I didn’t feel it, I didn’t feel as much rejection as in my country, but it was hard. (Depression) …especially if people do not have some kind of spiritual foundation, even a family foundation of support, it can be very difficult, it can be extremely difficult. (Spirituality) Estoy participando porque de alguna manera yo creo en la cura que se rompa el estigma, que se rompa todo lo negativo que hay alrededor del VIH. [I am participating because somehow I believe in the cure that breaks the stigma, all of that negativity surrounding HIV is broken.] (Stigma) |

Enhancers

Participants provided specifics as to what would increase their likelihood of participation. Four sub-themes of enhancers were identified: representation, building relationships, establishing connections, and participant partnerships. Within representation, participants identified the need for more racial/ethnic minorities to participate in research and more racial/ethnic minority researchers to be involved in the research process, including a role in gathering the data. They wanted people who “looked liked them” and Hispanics wanted people who spoke their language. In general they also preferred interviewers who were of their same gender. In building relationship, participants expressed their desire to be active partners in the research process. In the category of establishing connections, participants described the importance of being made comfortable by the researcher, being treated with respect, and trusting the researcher as precursors to engaging in a study. Within the subtheme of participant partnership, participants discussed how their contributions to the research were important to them because they believed in finding the cure for HIV.

Barriers

Barriers described by this cohort were negative reasons or perceptions associated with research that they had to overcome in order to enroll. These included lack of family acceptance, “guinea pig” perceptions, and obstacles to connection and preventing participation. Because of concern about not having the support and acceptance they wanted from their families concerning the HIV diagnosis, participants often kept information about their HIV status and/or their sexual orientation from their families. This led to strained relationships and worry that the family would find out they were HIV-infected if they participated in a research study. African Americans cited the Tuskegee study as an example of people being used as guinea pigs in research. In spite of this, these participants opted to participate in research and the determining factor was trust in their primary providers. Not feeling comfortable, feeling unwelcomed, or feeling disrespected by the research staff contributed to not trusting research and researchers and were perceived as obstacles to establishing connections with the research. Participants strongly emphasized the desire that researchers “not talk down to them,” that is, mistreat them based on misperceptions regarding income, race, and ethnicity and disease status.

Beliefs

Beliefs reflected the values from participants’ lived experiences that directly impacted their decision to participate in research. The sub-themes consisted of understanding research (they understood the purpose for conducting research and their roles as a research participant) and altruism (they were optimistic about finding a cure for HIV and felt strongly that their participation in research was contributing to this success). In addition to understanding the purpose of research, altruism fueled the desire to continue participating in research. These participants actively encouraged others in the community to become involved in research.

Psychosocial context

Participants in this study described the psychosocial context in which they responded to HIV infection, and several common themes emerged. This theme emerged from the data and provided a context for understanding how these individuals had struggled. Six sub-themes of psychosocial context where identified: response to diagnosis, sexual response, perseverance, depression, spirituality, and stigma. Many participants described the initial response to an HIV diagnosis as either preparing to die or being thankful for the disease (because it forced them to change their lifestyles); in either case it affected their personal goals. Participants were very concerned about the possibility of infecting someone else and, therefore, their sexual response was either to be “extra careful” or to avoid sexual relationships altogether. Some had been infected by people who knew they had HIV and had not shared it with them. When participants initially found out they were infected, they became depressed. They also described social discrimination and societal rejection experienced as a result of the stigma associated with being infected with HIV. Yet, in spite of discovering they had been infected with HIV and realizing that their lives had changed, participants decided to persevere and maintain a positive attitude. Overall, spirituality played a key role in the lives of these participants. Many turned to God for strength to deal with the disease while others blamed God for getting the disease. All of the sub-themes impacted the participants’ day-to-day lives and influenced their decisions to participate in research.

Discussion

This HIV study builds upon Mueller’s (2004) work by exploring participant thoughts and experiences around enrolling in clinical trials. Specifically, participants were asked what they hoped or expected to get from participating in research studies, what care and services they hoped to receive from their research professionals (nurses and doctors), and what they knew about the rights and responsibilities of human subjects participating in research studies. Our participants were fully aware that they were involved in a research study and able to articulate their rights and responsibilities as research participants.

For some, therapeutic misconception may have been a factor in deciding to enroll in a clinical trial. Described by Lidz and Appelbaum (2002), therapeutic misconception occurs when patients believe that participation in a clinical trial will provide the same treatment that they would receive in a non-research clinical encounter. In this case, the patient may not understand that there is a difference between clinical trial participation and receiving treatment. At times, patients can confuse the discussion with a physician about being in a clinical trial as a recommendation by the physician to enroll in the study (Bosk, 2002). Confounding the matter, the patient may give decision-making ability to a professional (in this case a physician) who they trust (Bosk, 2002). Although a trusting relationship with a health care provider was instrumental in the decision to participate in a clinical trial, it was not a blind trust. For all the participants, the provider provided information about research being done at the NIH, but it was up to the participant to follow-up with the referral.

Several studies have focused on decision-making in Hispanic patients with cancer. Ellington et al. (2003) conducted four focus groups related to participation in randomized cancer clinical trials with a total of 25 Hispanics. The four themes that emerged in their study were provider-patient relationship (personal and respectful), provider-patient communication (narrative stories to explain the decision-making process), informational and support needs (family involvement in decision-making), and discrimination (patient perceptions that the doctor thought they were low-income). In another paper by the same authors (Ellington et al., 2005), eight focus groups were conducted with 55 participants (25 Spanish-speakers and 30 English-speakers). In addition to the previous themes, faith/spirituality played a significant role with Spanish-speaking participants but not with English-speakers. Our study also included a focus group component. Similar themes emerged around the concepts of relationship with provider, respect, trust, and communication.

Research regarding the health behaviors of individuals of Hispanic/Latino descent in the United States must consider the general cultural heterogeneity of the population. The term Latino/Hispanic is representative of 22 different countries; they are not a homogenous group (Rivera-Goba & Nieto, 2007). For African Americans, social barriers associated with mistrust must be addressed (Allen et al., 2001). Treatment barriers such as providers making assumptions that patients will not adhere to treatment plans and, therefore, not offering them clinical research information must also be eliminated (Allen et al., 2001).

These data may help researchers develop strategies to facilitate inclusion of HIV-infected Hispanics and African Americans in clinical trials. Practical suggestions that can be used by researchers to increase recruitment of Hispanic and African American participants include: (a) match interviewer and participant by race/ethnicity, (b) match interviewer and participant by language spoken, (c) improve access by using a recruitment facility in the community, (d) develop trust, (e) establish a realistic time commitment, (f) provide remuneration in recognition of time commitment, and (g) share final results and outcomes with the participants.

Limitations

Because our participants were actively enrolled in clinical research, the decision to participate had already been made. Yet, it was exactly because of this experience that it was beneficial to obtain their perspectives. Another limitation of the study was that gender- and racial/ethnic-specific focus groups were not repeated. Future studies should include participants who have not yet been enrolled in clinical research and allow for repeated focus groups.

Conclusions

By asking participants to describe their research experiences, a better understanding may be gained of their decision-making processes. All participants stated they knew they were not “guinea pigs” but some would joke about being “guinea pigs.” Researchers must keep in mind the past experiences of these cultural groups, genuinely build relationships with participants, and create clinical environments in which the participants are treated with respect and as partners of the research team. Trust continues to be crucial in the development of relationships and researchers must continue to strive to build trusting relationships with participants. One way this can be achieved is to provide the results of the study to the participants, a request that came directly from our participants. The relationship between the patient and provider played a significant role in the individual’s decision to participate in research. This study sample was well informed about clinical trials and encouraged others to participate in studies. Knowing this, researchers can ask current participants to assist in reaching out to others in the community. This qualitative study provided insight into strategies for improving representation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Nancy Kline Leidy and Dr. Gwenyth Wallen for their thorough review of this paper. The authors also acknowledge Frinny R. Polanco for her contributions to this paper.

Footnotes

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Migdalia V. Rivera-Goba, Nursing and Patient Care Services, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD.

Dinora C. Dominguez, Patient Recruitment and Public Liaison Section, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD.

Pamela Stoll, Nursing and Patient Care Services, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD.

Christine Grady, Department of Bioethics, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD.

Catalina Ramos, Hematology Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD.

JoAnn M. Mican, Division of Clinical Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD.

References

- Allen M, Israel H, Rybczyk K, Pugliese MA, Loughran K, Wagner L, … Erb S. Trial-related discrimination in HIV vaccine clinical trials. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2001;17(8):667–674. doi: 10.1089/088922201750236942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosk CL. Obtaining voluntary consent for research in desperately ill patients. Medical Care. 2002;40(9):64–68. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000023957.23565.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caban C. Hispanic research: Implications of the National Institutes of Health guidelines on inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research [Monograph] Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;18:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargill VA, Stone VE. HIV/AIDS: A minority health issue. Medical Clinics of America. 2005;89(4):895–912. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among Hispanics/Latinos. 2009 August; Retrieved from http://cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/PDF/hispanic.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. 2010 September; Retrieved from http://cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/resources/factsheets/pdf/aa.pdf.

- Cohen MZ, Kahn DL, Steeves RH. Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans towards participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525.1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington L, Wahab S, Sahami S, Field R, Mooney K. Factors that influence Spanish- and English-speaking participants’ decision to enroll in cancer randomized clinical trials. Psych-Oncology. 2005;15(4):273–284. doi: 10.1002/pon.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington L, Wahab S, Sahami S, Field R, Mooney K. Decision-making issues for randomized clinical trial participation among Hispanics. Cancer Control. 2003;10(5):84–86. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford AL, Cunningham WE, Heslin KC, Andersen RM, Nakazono T, Lieu DK, Bozzette SA. Participation in research and access to experimental treatments by HIV-infected patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(18):1373–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA. Developing questions for focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998a. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA. Analyzing and reporting focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998b. [Google Scholar]

- Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS. The therapeutic misconception: Problems and solutions. Medical Care. 2002;40(9 Suppl):V55–V63. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000023956.25813.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable E. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183–205. doi: 10.1177/07399863870092005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M-R. Clinical, technical, and social contingencies and the decisions of adults with HIV/AIDS to enroll in clinical trials. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14(5):704–713. doi: 10.1177/1049732304263627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(22):2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. 2001 October; Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm.

- Newman PA, Duan N, Rudy ET, Anton PA. Challenges for HIV vaccine dissemination and clinical trial recruitment: If we build it, will they come? AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004;18(12):691–701. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powe NR, Gary TL. Clinical trials. In: Beech B, Goodman M, editors. Clinical trials in race and research perspectives on minority participation in health studies. Washington DC: American Public Health Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Goba MV, Nieto S. Mentoring Latina nurses: A multicultural perspective. Journal of Latinos and Education. 2007;6(1):35–53. doi: 10.1080/15348430709336676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Essien EJ, Torres I. Conspiracy beliefs about the origin of HIV/AIDS in four racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;41(3):342–344. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000209897.59384.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159(9):997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedlin MG, Decena CU, Oliver-Velez D. Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(7):32S–37S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment, confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone VE, Mauch MY, Steger K, Janas SF, Craven DE. Race, gender, drug use, and participation in AIDS clinical trials. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(3):150–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1525.1497.1997.012003150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Facts for features: Black history month 2009. 2008 Retrieved From http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/cb09-ff01.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Facts for features: Hispanic heritage month 2009. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb10-ff17.html.

- Wallen GR, Feldman RH, Anliker J. Measuring acculturation among Central American women with the use of a brief language scale. Journal of Immigration Health. 2002;4(2):95–102. doi: 10.1023/A:1014550626218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen GR, Rivera-Goba MV. From practice to research: Training healthcare providers to conduct culturally relevant community focus groups. Hispanic Health Care International. 2003;2(3):129–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, Van Wye G, Christ-Schmidt H, Pratt LA, … Emanuel E. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? Public Library of Science Medicine Journal. 2006;3(2):e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JR, Whelan TJ, Schiff S, Dubois S, Crooks D, Haines PT, … Levine MN. Why cancer patients enter randomized clinical trials: Exploring the factors that influence their decision. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(21):4312–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]