Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the deposition of amyloids in the brain. One prominent form of amyloid is composed of repeating units of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide. Over the past decade, it has become clear that these Aβ amyloids are not homogeneous; rather, they are composed of a series of structures varying in their overall size and shape and the number of Aβ peptides they contain. Recent theories suggest that these different amyloid conformations may play distinct roles in disease, although their relative contributions are still being discovered. Here, we review how chemical probes, such as congo red, thioflavin T and their derivatives, have been powerful tools for better understanding amyloid structure and function. Moreover, we discuss how design and deployment of conformationally selective probes might be used to test emerging models of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, thioflavin T, congo red, curcumin, fibrils, protofibrils, oligomers, amyloid beta

Amyloid-β (Aβ) is a short (38–42 residue) fragment of the amyloid precursor protein (APP). Under physiological conditions, Aβ peptides adopt a β-sheet-type secondary structure that is prone to self-assembly into higher-order structures, including dimers, trimers, oligomers, protofibrils and the fibrils that are characteristic of late-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. These conformations are defined by their signature appearances by electron and atomic force microscopy, their size on polyacrylamide gels, and even their method of preparation (Figure 1). Collectively, these aggregates are severely neurotoxic [1, 2] and some of them also appear to inhibit LTP and promote synaptic loss [3–5]. The most recent, emerging variants of the Amyloid Hypothesis propose that the pre-fibrillar amyloids, such as oligomers and other soluble structures (ADDLs, protofibrils, etc.) might play a particularly central role in disease [6–9]. However, despite advances in our understanding of Aβ biochemistry and AD pathology, the mechanisms of neurodegeneration are still not clear. One challenge is that amyloids, especially pre-fibrillar structures, are structurally heterogeneous and conformationally dynamic, which has complicated routine structural studies. Although progress has certainly been made using advanced methods, such as solid-phase NMR and computational simulations [10–13], many important questions remain. What molecular features do amyloids share? How do different amyloid conformers vary in their topology? What are the mechanisms of neurodegeneration and which specific features of amyloids contribute to toxicity? These are clearly pressing questions, as more than 35 million people suffer from AD and this afflicted population is expected to grow rapidly without a clear disease-modifying therapeutic available.

Figure 1. Aβ self-assembles into a variety of distinct conformations.

Monomers assemble into dimers, trimers and other low molecular weight (LMW) oligomers, which proceed to form larger oligomers and protofibrils. Mature fibrils have a characteristic, elongated morphology. Electron micrographs of enriched samples are shown.

Small molecules that bind to amyloids, such as the widely used thioflavin T (ThT) and congo red (CR), have been essential tools in the study of Aβ aggregation. In part, the strength of these compounds is their versatility; they have been used to monitor self-assembly in vitro, to recognize Aβ deposits in vivo, and to identify aggregation inhibitors. In addition, these compounds have been used to probe the structure of various amyloids and these studies have provided insights into the molecular features of the binding sites. Here, we review what is known about the binding of small molecules to amyloids and summarize what these studies have revealed about the relationships between amyloid structure and function.

Thioflavin T

Binding to aggregated Aβ enhances ThT fluorescence

ThT is a benzothiazole-based dye (Figure 2A) first noted to bind amyloid by Vassar and Culling in 1959 [14] and later used in studying patient-derived amyloids by Naiki and coworkers [15–17]. These groups noted that the fluorescence of ThT is quenched in solution, but that its quantum yield is greatly increased when bound to the β-sheet structure of amyloid fibrils [18]. This same phenomenon was observed with synthetic Aβ fibrils [19], and ThT was adapted by LeVine into a convenient, inexpensive assay for monitoring fibril formation in vitro [20]. This protocol has been largely unchanged and is perhaps the most widely employed method for monitorings Aβ aggregation.

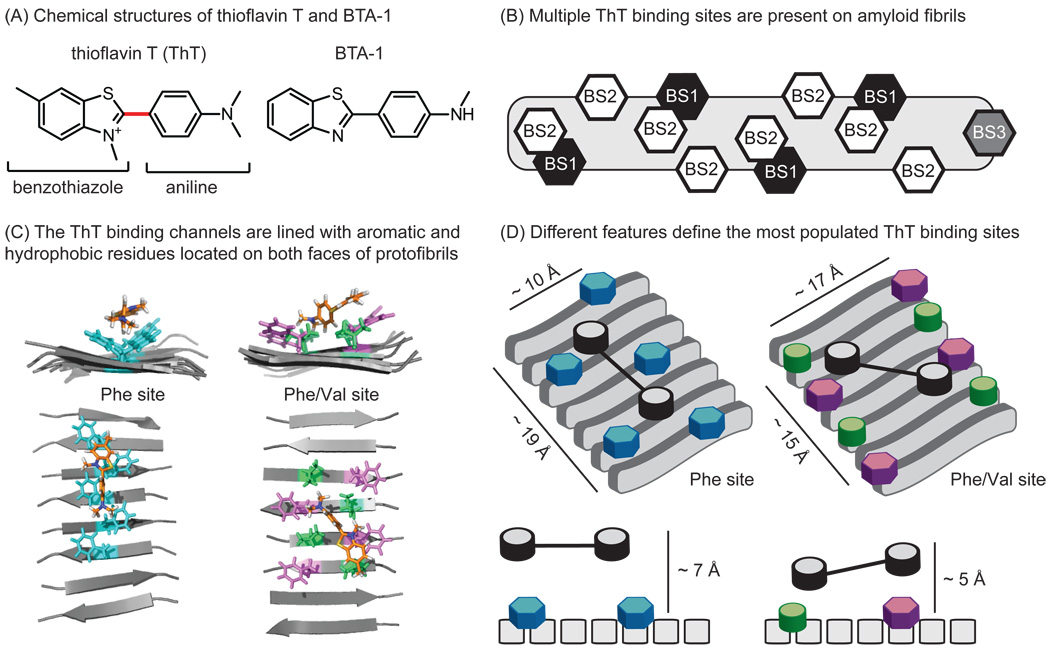

Figure 2. Thioflavin T (ThT) binds amyloids at multiple sites.

(A) Chemical structures of ThT and a neutral analog, BTA-1, highlighting the major components: a benzothiazole ring system attached to functionalized aniline. The linker between these modules is shown in red. (B) Amyloids contain three distinct ThT binding sites, two with high density (BS1 and BS2) and one with low density (BS3). (C) Snapshots from MD simulations illustrate ThT binding within two channels lined with either Phe residues (left) or both Phe and Val residues (right) [27, 28]. (D) A schematic model of the two ThT binding sites, illustrating their unique molecular features. The same color scheme is used in parts C and D.

ThT fluorescence is thought to increase when bound to Aβ fibrils because of changes in the rotational freedom of the carbon-carbon bond between the benzothiazole and aniline rings (Figure 2A) [18, 21, 22]. In the unbound state, the ultrafast twisting dynamics around this bond are thought to cause rapid self-quenching of the excited state, resulting in low emission. However, upon binding to fibrils, the rotational freedom is apparently restricted and the excited state is readily populated. This concept was recently confirmed using a series of synthetic ThT analogs, which varied in their flexibility [22]. The practical outcome of this mechanism is that ThT and its analogs can be used to spectroscopically quantify the amount of amyloid in a sample.

Binding modes of ThT to amyloid fibrils

The dramatic response of ThT’s fluorescence to amyloids suggests that a defined binding event takes place to restrict the motion of the compound. Thus, studying this interaction would be expected to reveal insights into the local amyloid topology and its molecular features. This strategy has been productive, with solid-state NMR [10], radiolabeling [23, 24], competition assays [25], and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [26–28] all having been used to evaluate ThT binding to amyloids. One of the first important observations was made by LeVine, who proposed that there are multiple binding sites for ThT on amyloids [25]. Lockhart et al. further refined this model using fluorescence and radiolabel-based assays [23]. Together, these studies suggested the presence of three distinct binding sites (BS1, BS2, and BS3) on Aβ fibrils. Sites BS1 and BS2 are relatively abundant, with approximately one site per 4–35 Aβ monomers (Figure 2B). The less abundant site, BS3 is found at approximately one site for every 300 monomers. Based on FRET measurements, binding sites BS1 and BS2 are thought to be in close proximity, however occupancy was found to be neither cooperative nor competitive.

Further insights into how ThT binds in these different sites was supplied by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [27, 28]. Briefly, Wu et al. simulated ThT binding to protofibrils composed of Aβ (16–22) and characterized the formation of three unique, populated clusters [27]. Consistent with their earlier findings [28], the least populated binding cluster was located on the end of the protofibril in an orientation anti-parallel to the fibril axis. The two other clusters were more heavily populated and located parallel to the fibril axis (anti-parallel to the β-sheet). Together, these results seem to confirm Lockhart’s model of two, high-density ThT sites (BS1, BS2) and a single low-density site (BS3) (Figure 2B). In this model, BS1 and BS2 are composed of surface grooves created by aligned side-chains in the fibril axis, which provide much of the binding energy. When bound in these grooves, MD simulations suggest that the ring systems adopt a planar organization, with the charged nitrogen exposed to solvent [26,29] (Figure 2C). Interestingly, similar grooves have been proposed in amyloid fibrils composed of many different proteins (e.g. α-synuclein, prions, etc.), which may explain why ThT fluorescence is also sensitive to other, unrelated amyloids. However, because different amyloid-forming peptides do not share a high sequence identity, these results also suggest that some degenerative feature(s), such as hydrophobicity or contacts with the peptide backbone, are responsible for ThT binding.

Consistent with this idea, a closer examination of the molecular models reveals interesting features of the two most populated ThT binding sites (Figure 2C) [27]. These two binding channels are lined with at least five, spatially consecutive, hydrophobic (Phe only or Phe and Val) side chains, which are located on opposite ‘faces’ of the amyloid structure. Similar findings have been observed by Koide and coworkers, who developed peptide self-assembly mimics (PSAMs) that have repetitive, β-sheet amyloid-like structure [30–32]. These soluble model proteins are amenable to crystallization, and co-crystals with bound ThT revealed that the compound binds in channels lined with five or six aromatic and hydrophobic side-chains [31]. Interestingly, it is critical that the favorable, hydrophobic residues within the channel are spatially consecutive, as two adjacent clusters of Tyr residues separated by a Lys and Glu showed no ThT binding [31]. Collectively, these observations converge on a model in which five, aligned aromatic and/or hydrophobic residues are critical for ThT binding, while the exact identities of the side chains appear to be less important than their overall hydrophobicity.

An alternative binding mode was suggested by Groenning et al. using spectroscopy and molecular modeling to examine ThT binding to insulin fibrils. Although they confirmed that at least two distinct binding sites exist, with ThT binding predominantly parallel to the fibril axis [33, 34], they further suggest that two ThT molecules in an excited-state dimer, or ‘excimer,’ form, might bind to the grooves. Thus, a higher-order form of ThT, even as large as a micelle [35], might be involved in binding under some conditions and for some amyloids.

ThT also recognizes pre-fibrillar Aβ aggregates

As mentioned previously, pre-fibrillar intermediates are now thought to correlate with neurodegeneration, which has prompted interest in evaluating ThT binding to these structures. In the literature, there was initially debate over whether ThT binds oligomers and protofibrils. In fact, several groups initially defined ThT as a fibril-specific probe [36–39]. However, methods for preparing pre-fibrillar structures have become more reliable and comprehensive studies have now noted clear changes in fluorescence when ThT is added to pre-fibrils [40–42]. For example, Walsh et al. prepared samples of protofibrils and observed that they produce a concentration dependent increase in ThT fluorescence [42]. The binding of ThT to pre-fibrils is consistent with the binding information discussed above, as these structures are known to be rich in the hydrophobic, β-sheet content important for binding [42]. For example, models of Aβ protofibrils have the requisite stretch of aligned hydrophobic residues one might expect to form the high-abundance ThT-binding site [43]. However, fibrils and pre-fibrils are not identical in their binding to ThT, as many groups have noted that the maximum fluorescence induced by pre-fibrils is less (per mole of Aβ) than that stimulated by fibrils. For example, ThT fluorescence is modestly increased (1.5-fold) in the presence of Aβ oligomers [41] of either 1–40 or 1–42 Aβ [40], while fibrils often yield over 100-fold improvements in fluorescence [44]. Moreover, using SPR, ThT (Kd = 498 nM) was shown to bind Aβ oligomers, but the total number of bound molecules was significantly less than in fibrils [40]. These observations and others are likely consistent with other findings, because protofibrils are proposed to be more dynamic [45] and contain relatively fewer ThT-binding sites [46, 47].

Interactions of ThT analogs with Aβ

Additional insights into the nature of the ThT-binding groove can be gained from studying synthetic ThT derivatives in which the molecular features of the molecule are systematically varied. In general, these derivatives are composed of a benzothiazole ring system attached to a substituted aniline (Figure 2A). Derivatives of this scaffold tend to have modifications at the amine of the aniline and at positions around the benzothiazole. Fortunately, many analogs have been explored as part of studies to develop imaging agents and, in many cases, the binding affinity of these compounds for amyloids has been reported. For example, Klunk et al. synthesized several neutral ThT analogs, such as BTA-1, to explore the effect of the positive charge on the benzothiazole ring (Figure 2A) [48]. They found that each neutral analog bound better to Aβ than ThT, with the best having a 40-fold improved affinity. These findings suggest that the positive charge in ThT may be detrimental for binding, which is a model supported by MD simulations indicating that the neutral BTA-1 is able to bind deeper into the hydrophobic binding grooves [27]. However, ThT does not entirely compete with BTA-1 for binding [25], and Lockhart et al. observed different binding patterns between the two ligands [23]. In silico data further reveals that the ring systems of BTA-1 are planar in the bound orientation, instead of in a slightly twisted orientation, as observed with the charged ThT scaffold [27]. Collectively, these data support a model in which some of the “ThT binding sites” (i.e. BS1, BS2 and BS3) are more favorable for ThT, while others prefer neutral ligands. Interestingly, removal of the positive charge does not seem to affect oligomer binding, suggesting that one of the binding sites may be more prevalent in pre-fibrils [49]. One possibility is that some of the sites allow deeper binding grooves, perhaps permitting neutral ligands with increased access. This idea is supported by measurements of the dimensions of the two sites identified by modeling: one has an average depth (backbone to solvent) of 5.4 Å, while the other is 7.1 Å. This deeper site might allow better penetration of neutral derivatives and, consequently, more favorable buried surface area and better affinity. These sites are unique in other dimensions as well; the shallower site is wider (17 Å), while the deeper site is narrower (10 Å). It isn’t yet clear which site is BS1 or BS2, but these differences support the model that the two sites have distinct properties. To our knowledge, structure-guided design has not yet been used to rationally exploit these differences.

Synthetic ThT derivatives have also been useful in further refining the features of the binding sites. For example, the benzothiazole can be replaced by a roughly planar benzofuran, imidazo-pyridine, imidazole, or benzoxazole core, without impacting affinity [49–52]. Additionally, the aniline may be replaced with other flat, rigid moieties (e.g. stilbene, cyanobenzyl) without significant consequence [53, 54]. Insertion of a planar styrene group between the benzothiazole and aniline is also well-tolerated [53], while some substitutions, such as bithiophenes, even improve affinity [55]. In addition, these substitutions need not be aromatic, because methyl-piperazine groups appended to the aniline are tolerated [56]. Interestingly, some of these substitutions extend the end-to-end distance of the ThT-like molecule by over 25%, suggesting that the binding channel can accommodate relatively long molecules, as long as they are planar and hydrophobic. However, there are limitations to the size of this channel, because installation of a large, freely-rotatable rhenium chelate to the aniline abolishes binding [57]. Appending the same group to the opposite end of the molecule actually enhanced binding by 8-fold, which suggests that the dimensions of the channel are limited in some regions.

More subtle substitutions to the benzothiazole and aniline groups also help define the nature of the ThT binding site(s). For instance, the di-methyl amine group can be moved to the benzothiazole on the opposite side of the molecule without any consequence to binding affinity [58], suggesting that ThT derivatives may be able to bind in either orientation (Figure 2D). However, small alkyl-type substitutions in key positions appear to impact the binding mode [59]. For example, a methyl group at the 6-position of the benzothiazole ring is favored only if no methyl substitutions are present on the amine of the aniline (Ki = 9.5 nM). Alternatively, two methyl groups on this amine were favored if the 6-position was hydrogen (Ki = 4 nM). Interestingly, a more polar, hydroxyl at the 6-position was tolerated only if the aniline was substituted with at least one methyl group, suggesting that overall hydrophobicity is a critical element for binding.

In summary, multiple experiments have converged on a model in which amyloids contain up to three different binding sites. The two major sites (BS1 and BS2) are parallel to the fibril axis and are sensitive to relatively modest increases in steric size in some positions, while they can be readily elongated in the channel if overall planarity is maintained (Figure 2D). The major contacts with ThT are through aromatic and/or hydrophobic side-chains in the parallel groove, and neutral derivatives bind tighter than their charged counterparts. It is important to note that BS1 and BS2 are present in roughly equivalent numbers (at least on fibrils) and that the experiments discussed here often focus on the composite affinities. Differences in the way that ThT derivatives bind the different sites might easily be masked in these studies and, moreover, little is likely learned about the requirements at BS3 in these types of experiments.

Congo Red

CR binds at least two sites on amyloids

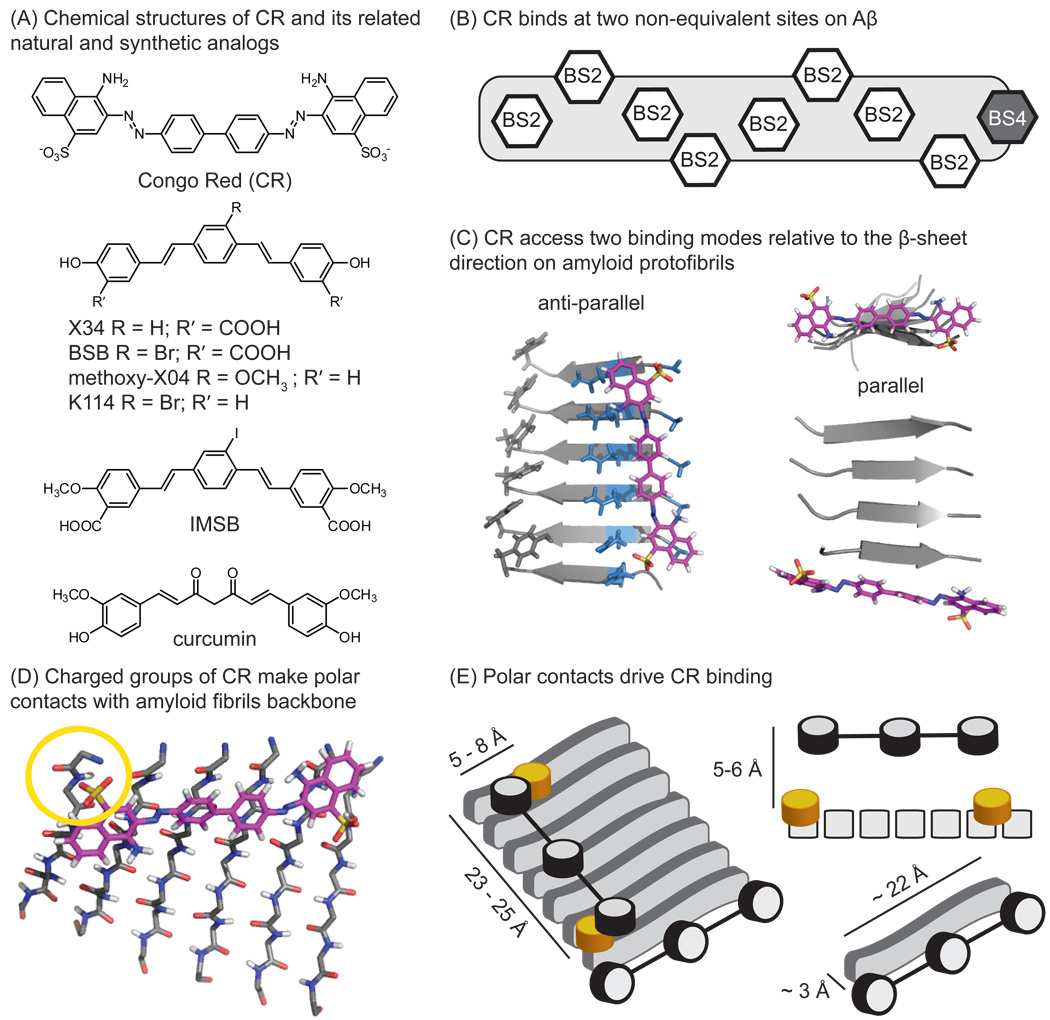

Congo Red (CR) staining serves as a positive indicator of amyloid deposition and its optical properties have been extensively reviewed [60,61]. Briefly, CR selectively stains amyloid in vitro and in brain slices, and bound material displays a characteristic birefringence under polarized light. Like ThT, binding is observed with both Aβ-derived amyloids and amyloids derived from other peptides, suggesting that shared elements, such as β-sheet structure or peptide backbone, are involved in binding. Consistent with this idea, molecular docking simulations suggest that CR binds one site parallel to the fibril axis (anti-parallel to the β-sheets) [62] on amyloid fibrils [28, 63, 64] and protofibrils [28]. Based on the approximate length one of the CR molecule (~19 Å) (Figure 3A), Klunk and colleagues proposed a model in which it requires at least five Aβ monomers for binding [62]. Lockhart et al. further characterized the number and types of CR-binding sites using a close analog, BSB [24]. These studies revealed two non-equivalent binding sites, one of which is shared by ThT and is present at one site per three Aβ monomers. Moreover, the shared binding site was found to be the highest-density ThT binding site (BS2) (Figure 3B). These findings clarify the seemingly contradictory, earlier observations that CR and ThT have discrete binding sites [56], while other groups have reported competition [25, 65]. To keep consistent with the existing nomenclature and as a useful tool for discussion in this review, we identify the unique CR-binding site as BS4. Insight into the nature of BS4 came from studies on a prion-derived, amyloidogenic peptide with the sequence GNNQQNY [28]. Specifically, MD simulations revealed that CR favors binding parallel to the fibril axis (anti-parallel to the β-sheets), but that it also populates a second site at the ‘end’ of the protofibril in an orientation anti-parallel to the fibril axis and parallel to the β-sheets (Figure 3C). This latter mode only represented approximately 11% of the total CR binding clusters, while the anti-parallel orientation was clearly preferred (78% of the total binding). This model perhaps explains the difference between CR binding affinity (Kd high nM – low µM) and its inhibition capacity (IC50 mid-high µM). In other words, CR may preferentially bind anti-parallel to the β-sheet, but this binding mode is not likely to inhibit fibril extension. When BS2 becomes saturated, CR may bind BS4 at the face of the growing fibril, only then disrupting monomer acquisition and elongation.

Figure 3. Congo Red (CR) accesses two distinct binding sites on amyloids.

(A) Structures of CR and its analogs. (B) The two CR binding sites on amyloid are shown, one with high density (BS2) and the other with low density (BS4). (C) Model of the high density site, parallel to the fibril axis, and the low density site at the end of the fibril. In the high density site (BS2), the channel is largely composed of polar, uncharged residues. (D) Close-up of the BS2 site, highlighting the interaction with the charged sulfonic acid at the end of the CR molecule. Adapted from [28]. (E) Schematic model of bound CR in the BS2 site, with the molecular dimensions and features shown.

Similar to ThT, the main CR binding mode appears to be defined by a channel formed from side-chains. The CR-binding channel is longer (23–25 Å), and narrower (5–8 Å) than the ThT channels, although it must include a portion of ThT-binding BS2 site based on the competition results. However, in contrast to the ThT channel, the residues that line the CR-binding site are largely polar and non-aromatic, such as Asn and Gly. In addition, despite the presence of nearby tyrosines, these aromatic residues do not appear to participate in CR binding (Figure 3C, left). Instead, in three of the four most populated clusters, the sulfonic acid moieties were aligned with the N-terminus, the only positive charge on the specific peptide used in thee experiments (Figure 3D). These data suggest that ionic or polar interactions may be important for CR binding. Even greater detail has been provided by molecular docking of CR to 20 NMR structures [66] composed of near full-length Aβ (9–40) [67]. These results confirmed two distinct CR binding sites, one located near Lys28 and the other at the C-terminus, making contacts with Asn27 and Val39. This is one of the first studies to implicate specific residues of the Aβ peptide in CR binding and, further, the contacts with Lys28 and Asn27 were confirmed by mutagenesis. Accordingly, these results suggest that, in the context of full length Aβ, Lys28 may provide the requisite positive charge to interact with the sulfonic acids. Thus, the identity of the side-chains seems to play less of a role than polar contacts at the termini of the pocket.

CR binds pre-fibrillar amyloids

The first indication that CR may recognize pre-fibrils was by Walsh et al., who showed that CR absorbance was altered by Aβ protofibrils [42]. In addition, CR and BSB have been found to bind globular Aβ oligomers (Kd = 3.2 – 19.5 µM) by SPR [40]. Interestingly, solution-state NMR has recently revealed that CR binds low-molecular weight Aβ species as well [68]. It isn’t yet clear whether the fundamental features of the CR binding site(s) on early Aβ oligomers are similar to those defined for fibrils. However, similar to what has been observed with ThT, the absolute number of binding sites appears to be reduced compared to fibrils.

CR analogs reveal features of the amyloid-binding sites

Synthetic CR derivatives have provided further insight into the features of the binding sites on amyloids. For example, early analogs explored the requirements for the sulfonic acids [62]. Using a radiolabeled displacement assay, Klunk et al. identified that other charged groups, such as carboxylic acids, could replace the sulfonic groups [62]. More recent studies found that the carboxylates were not absolutely required if phenolic hydroxyls were included [69]. Further SAR studies revealed that the methoxy substitutions that are located on some CR analogs are expendable [56,70]; thus, there are likely no specific contacts made with those groups.

In addition to the contacts at the termini, the overall planarity of the molecules appears to be critical to their binding. Effective CR analogs, including X34 [71], BSB [72], K114 [73], IMSB [56], and methoxy-X04 [74], are all aromatic and planar and they seem to share binding sites [73] (Figure 3A). Other derivatives, based on the curcumin scaffold, revealed that two terminal aromatics are necessary [70]. Interestingly, the overall size of the molecule was found to follow strict requirements, with the linker length restricted to 8–16 Å and including no more than 2–3 rotatable bonds. This general conclusion is supported by studies that indicate the more rigid enol form of curcumin is favored to bind Aβ, relative to the more flexible keto form [75, 76]. Together, these findings are consistent with a model in which the binding site for CR has limited size, with a hydrophobic channel and polar (or positively charged) groups at the ends (Figure 3D). These same molecular contacts may be equally crucial in pre-fibrillar conformations, because curcumin also inhibits the formation of low-molecular weight (LMW) and oligomeric Aβ [77].

Peptides

The hydrophobic core region (HCR) is critical for Aβ aggregation

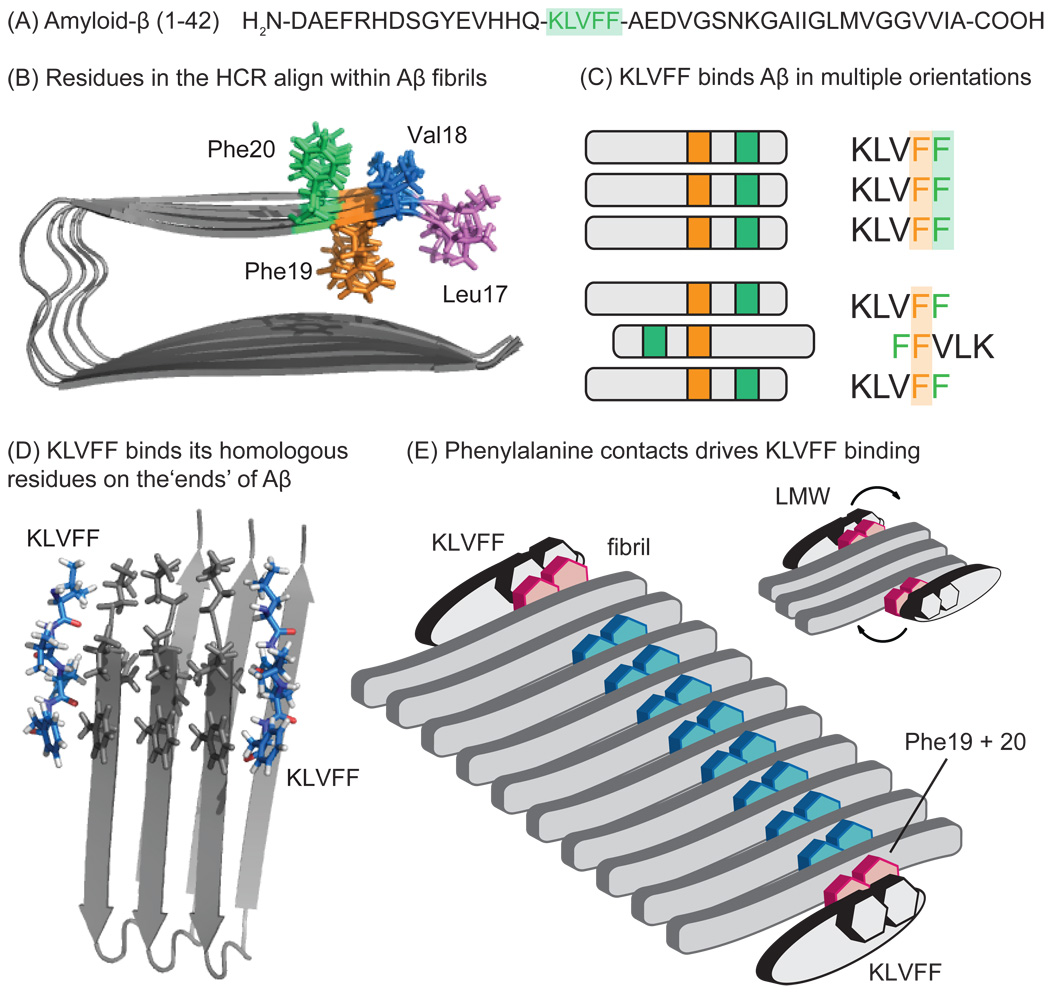

The hydrophobic core region (HCR) of Aβ spans residues 16–20 (KLVFF) and is thought to be one of the most critical elements for Aβ self-assembly (Figure 4A). This model arose from experiments, such as those reported by Tjernberg et al., in which they tested binding of Aβ peptides to full-length Aβ (1–40) and found that only three truncations (residues 10–19, 11–20, or 12–21) were capable of significant binding [78]. Further studies showed that systematic substitution of the hydrophobic residues 17–20 in Aβ (10–42) for more hydrophilic amino acids reduces fibril formation [79]. Moreover, point mutations in Val18, Phe19 and Phe20 are sufficient to block aggregation [79, 80], suggesting that these residues play a particularly important role. Further, the hydrogen-bond network associated with the amide backbone of KLVFF is critical in determining aggregate morphology [81]. Together, these findings suggest that the HCR, and especially KLVFF, may be an attractive target for probe development.

Figure 4. KLVFF bind at the exposed ‘ends’ of Aβ aggregates.

(A) The sequence of Aβ (1–42), with the hydrophobic core region (HCR) highlighted in green. (B) The side-chains of the KLVFF (colored) align within the stacked β-sheets of fibrils, leaving one motif free at each end. (C) KLVFF interacts with amyloids in two orientations; either the homologous residues align (left) or the sequence is reversed and shifted (right). The parallel mode is favored in fibrils, while the anti-parallel orientation pre-dominates in non-fibrillar oligomers. Regardless, Phe-Phe contacts seem to be crucial for binding. (D) Model of KLVFF aligned with its cognate sequence in a fibril. Adapted from solid-state NMR structures (PDB:2BEG) [13]. (E) Schematic model illustrates that KLVFF binds at the ends of fibrils and smaller oligomers (inset), with Phe residues being critical to the assembly. In smaller oligomers, KLVFF might bind anti-parallel to its cognate sequence.

KLVFF motifs are aligned in Aβ fibrils and free sites are available at the “ends”

Mature fibrils have a largely parallel β-sheet structure, such that the residues in this region are aligned (e.g. Phe 19 from one strand is stacked against Phe 19 from the next monomer) (Figure 4B). Even in pre-fibrillar samples, which contain both parallel and anti-parallel β-sheets [82, 83], KLVFF regions are thought to be partially aligned, especially at the core Phe19 residue [84, 85]. These observations suggest that free KLVFF peptides will tend to align with their corresponding residues in both pre-fibrillar and fibrillar amyloids. Consistent with this idea, early structure-activity studies revealed that the peptides KLVFF, QKLVFF, HQKLVFF, KLVFFA, KLVFFAE, and QKLVFFA bound with the best affinity to Aβ (1–40) fibrils [86]. This hypothesis was later confirmed using 38 fluorescently-labeled 5-mer fragments [87]. Interestingly, Ma and Nussinov found that KLVFF interacts within Aβ oligomers in two orientations; one in which KLVFF binds its identical, homologous residues on the neighboring molecule, and one in which this directionality is reversed and shifted (Figure 4C) [63].

Another critical feature of the KLVFF-binding site is that it will be exposed at the ‘ends’ of aggregates (Figure 4D). Indeed, extensive hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX) and solution-state NMR studies have shown that these residues are poorly solvent-accessible in the core of fibrils [83, 88, 89] while they are more exposed in pre-fibrillar species. For example, only Leu17 and Val18 within the HCR are buried in LMW Aβ and only Leu17, Val18 and Phe19 In globular oligomers [88]. Thus, opposite to what was discussed for the ThT- and CR-binding sites, there may be more KLVFF-binding sites in early amyloid species [11]. Moreover, in the context of this review, these observations are of particular interest because they suggest that KLVFF-based probes might be used to understand the chemical and structural environment around the free “ends” of amyloids. As discussed above, ThT- and CR-like ligands populate this region (BS3 and BS4), but with low abundance and weak affinity.

Interactions of KLVFF derivatives with Aβ

Because the natural KLVFF sequence aligns with itself in amyloids, structure-activity studies on modified peptides can be used to probe the structural requirements in this region. For example, Cairo et al. used SPR to determine the affinity of 24 KLVFF-based ligands for fibrils [90]. They discovered that KLVFF has a low binding affinity (Kd = 1.4 mM), consistent with its inability to inhibit aggregation [91, 92]. The specific requirement for aromatic side-chains was demonstrated by the 10-fold loss in affinity upon removal of the terminal Phe residue and the 3-fold loss in affinity upon replacement of Phe with His residues (KLVFH, KLVHH). In contrast, systematic substitution of the Phe residues for Tyr (KLVYF, KLVFY) did not dramatically alter affinity (Kd = 1.6 – 2.4 mM). However, there appears to be limits to these substitutions because introduction of a Trp residue (KLVFW) or two Tyr residues (KLVYY) was not well tolerated. Interestingly, the all D-KLVFF stereoisomer shows no difference in binding affinity [90, 93], suggesting that the identity and order of the residues is more important than their position relative to the backbone. Consistent with this idea, substitution of the amide bond with either ester or N-methyl groups has little effect [94–96]. Collectively, these findings suggest that the side-chains of KLVFF are critical for recognition, but that the backbone does not significantly participate in binding of free peptide.

Although the core KLVFF sequence itself is somewhat sensitive to relatively minor changes, additions to either end seem well tolerated. For instance, appending polar residues, including stretches of lysines or arginines (KLVFFK4, KLVFFK6, and KLVFFR6) significantly improves affinity (Kd = 37–80 µM) [90]. It seems likely that these residues make favorable contacts with residues adjacent to the HCR to add additional binding energy. Further, the addition of the lysines was preferred on the C-terminal end of the molecule, as KLVFFK4 displayed nearly a 5-fold better affinity than K4LVFF. Similarly, addition of bulky moieties to the N-terminus of KLVFF are tolerated, and, in some cases, improve recognition. For example, replacement of the lysine of KLVFF with a sterol had no effect on Aβ binding [97] and Gordon et al. showed that an N-terminal anthranilic acid improves binding 5-fold [96].

Together, these studies lead to a model in which KLVFF binds to sites at the ends of amyloids in either a parallel or anti-parallel mode (Figure 4E). The side-chains, specifically the Phe residues, predominantly drive binding, with little contribution from the peptide backbone. Further, polar and non- polar groups could be appended to KLVFF to enhance its binding. In this regard, KLVFF may be a useful ‘anchor’ molecule for probing the surrounding regions at the ends of Aβ aggregates.

Conformation-specific probes

Aβ assembles into amyloids with a variety of distinct conformations

Extensive NMR [83, 98, 99], microscopy [100–102], hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX) [45, 83, 88, 103], Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy [82, 104], stability measurements [105], and molecular dynamics [11, 63] studies have suggested that Aβ can form multiple types of amyloid structures, including LMW (e.g. dimers, trimers, etc.) structures, soluble oligomers, protofibrils and fibrils. These structures differ in their overall size, shape, and the number of monomers they contain. In addition, a major theme in recent reports is that fibrils tend to be densely packed, while pre-fibrillar conformations are “looser” or more dynamic in structure. For example, Wetzel’s group showed that the core of Aβ fibrils is extremely resistant to solvent exchange [103], while Qi et al. demonstrated that oligomers incorporate deuterium at a rate 10- fold greater than fibrils [45]. These types of studies have also carefully mapped the residues in oligomers that are most accessible [83, 88]. Based on these structural differences, it seems likely that small molecules might be able to exploit the unique structural features that differentiate conformers. Consistent with this idea, numerous studies have reported small molecules that specifically block the formation of one type of amyloid conformation, without impacting others [106–109].

Conjugated polymers respond to Aβ conformation

Nilsson, Hammarstrom, and coworkers have performed pioneering studies using luminescent-conjugated polymers (LCPs) to selectively detect amyloids [110–114] (Figure 5A). When these polymers engage their target, they are designed to adopt a backbone orientation that conforms to the size and shape of the bound structure. This re-arrangement aligns the polymer scaffold and alters the apparent fluorescence properties, yielding an “optical fingerprint” specific to the bound amyloid. Using multiphoton microscopy, deposits in brain tissue have been labeled with several LCPs, revealing the presence of multiple, optically unique morphologies within a single plaque [113]. Recent studies by these groups have also revealed smaller, pentameric thiophene derivatives (Figure 5A) that retain conformation-selective spectral binding properties [111]. Included in these novel derivatives is the anionic ligand p-FTAA, which recognizes pre-fibrillar Aβ species in vitro and labels Aβ deposition in transgenic mouse models, indicating that these BBB-permeable derivatives may be informative for monitoring distinct conformations in vivo [111, 112]. It remains unclear precisely which Aβ conformations are bound by these probes or which ones correlate best with the toxic species. However, these findings do suggest that distinct amyloid morphologies co-localize in diseased brain tissue.

Figure 5. Chemical structures of some conformationally-selective Aβ probes.

The structures of various, reported molecules are shown. See the text for details.

Indoles selectively detect pre-fibrillar amyloid

We recently reported an unbiased screening approach to identify compounds that interact with pre-fibrillar, but not fibrillar, amyloids [105, 115]. These efforts identified indole-based compounds that only undergo a change in fluorescence in the presence of pre-fibrillar structures, with a selectivity coefficient nearly 20-fold greater than ThT (Figure 5B). By optimizing the chemical structure of the indole and the reaction conditions (e.g. buffer, time, etc.), one promising probe, TROL, was developed into a “ThT-like” spectroscopic assay for pre-fibrillar amyloids [115]. These findings suggest that some of the indoles access a site on pre-fibrillar Aβ that likely becomes buried or otherwise inaccessible upon fibril formation. Although the binding site and mechanism is not yet clear, these probes further demonstrate that pre-fibrillar and fibrillar amyloids have different molecular features that can be exploited by small molecules.

Selective Aβ probes based on peptides

In addition to screening approaches, rational design has been used to develop conformationally sensitive probes. For example, Hu et al. developed a peptide-based probe, PG46, in which a portion of the Aβ (1–40) was replaced with a binding epitope for the fluorescent dye, FLaSH [116] (Figure 5C). When this modified peptide was added to different amyloids, they found that its fluorescence was only sensitive to intermediate aggregates (e.g. oligomers), but not LMW or fibrillar amyloids, likely because of differences in the local environment of the fluorophore. In addition, we recently developed bivalent KLVFF derivatives that specifically bind LMW trimers and tetramers of Aβ [117] (Figure 5D). Using molecular modeling, we estimated the distances between exposed KLVFF binding sites on the “ends” of Aβ dimers, trimers, and tetramers. Then, corresponding ligands were assembled by solid-phase peptide chemistry with L-amino acids and a biotin tag was incorporated. Using polyacrylamide electrophoresis, we found that the bivalent KLVFF probes bound primarily to the trimer and tetramer, with some binding to dimer. These findings are consistent with recent MD simulations, which suggest that the Aβ (9–42) dimer is highly dynamic and may exist in orientations that are distinct from other conformations [11]. In addition, no binding to monomers or higher order oligomers was observed. Although in its infancy, the field of conformational-selective probes holds promise in understanding amyloid structure and function.

Conclusions and Prospectus

Classic amyloid probes like ThT and CR have played a key role in our understanding of amyloid structure. As the appreciation of the number of different conformations has broadened, these scaffolds have found exciting, new roles. However, the classic probes tend to have relatively poor selectivity. Thus, the development of next-generation ligands will be an important step in further accelerating our understanding of the roles of amyloids in disease. Towards that goal, one approach that might be particularly fruitful is the use of multivalent ligands. The synthesis of bivalent, ‘molecular tweezers’ that bind amyloids have been reported [92, 93, 117–121] and we expect that these types of scaffolds may be incorporated into the next battery of tools. In turn, these designed ligands might be used to ask the next generation of questions about amyloid structure and function. Where are the small molecule-binding sites positioned in relation to one another? How does the position or number of these sites change upon transition from one conformation to another? A combination of old and new chemical probes will likely be necessary to answer these questions and others.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Yong Duan of UC-Davis for kindly allowing access to PDB files of docked ThT and CR molecules and Dr. Harvey Swick for reading the manuscript. Our work on amyloid ligands is funded by the Alzheimer’s Association (NIRG 89471 and IIRG 60067). A.A.R. was supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship from the NIH/NIA Biogerontology Training Grant (AG000114).

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- CG

Chrysamine G

- CR

Congo Red

- FRET

Forster resonance energy transfer

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- HCR

hydrophobic core region

- HDX

hydrogen-deuterium exchange

- LMW

low-molecular weight

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MD

molecular dynamics

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- ThT

thioflavin T

References

- 1.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr., Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002 Aug 30;277(35):32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008 Aug;14(8):837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, et al. Alzheimer's disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Sep 2;100(18):10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klyubin I, Walsh DM, Lemere CA, Cullen WK, Shankar GM, Betts V, et al. Amyloid beta protein immunotherapy neutralizes Abeta oligomers that disrupt synaptic plasticity in vivo. Nat Med. 2005 May;11(5):556–561. doi: 10.1038/nm1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2008 Sep 1;192(1):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira ST, Vieira MN, De Felice FG. Soluble protein oligomers as emerging toxins in Alzheimer's and other amyloid diseases. IUBMB Life. 2007 Apr–May;59(4–5):332–345. doi: 10.1080/15216540701283882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Feb;8(2):101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein WL, Stine WB, Jr., Teplow DB. Small assemblies of unmodified amyloid beta-protein are the proximate neurotoxin in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004 May–Jun;25(5):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Nuallain B, Freir DB, Nicoll AJ, Risse E, Ferguson N, Herron CE, et al. Amyloid beta-protein dimers rapidly form stable synaptotoxic protofibrils. J Neurosci. 2010 Oct 27;30(43):14411–14419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3537-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balbach JJ, Ishii Y, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Rizzo NW, Dyda F, et al. Amyloid fibril formation by A beta 16–22, a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer's beta-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry. 2000 Nov 14;39(45):13748–13759. doi: 10.1021/bi0011330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horn AH, Sticht H. Amyloid-beta42 oligomer structures from fibrils: a systematic molecular dynamics study. The journal of physical chemistry. 2010 Feb 18;114(6):2219–2226. doi: 10.1021/jp100023q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klimov DK, Thirumalai D. Dissecting the assembly of Abeta16–22 amyloid peptides into antiparallel beta sheets. Structure. 2003 Mar;11(3):295–307. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luhrs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Dobeli H, et al. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta(1–42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Nov 29;102(48):17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vassar PS, Culling CF. Fluorescent stains, with special reference to amyloid and connective tissues. Arch Pathol. 1959;68:487–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naiki H, Higuchi K, Hosokawa M, Takeda T. Fluorometric determination of amyloid fibrils in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavin T1. Anal Biochem. 1989 Mar;177(2):244–249. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naiki H, Higuchi K, Matsushima K, Shimada A, Chen WH, Hosokawa M, et al. Fluorometric examination of tissue amyloid fibrils in murine senile amyloidosis: use of the fluorescent indicator, thioflavine T. Lab Invest. 1990 Jun;62(6):768–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naiki H, Higuchi K, Nakakuki K, Takeda T. Kinetic analysis of amyloid fibril polymerization in vitro. Lab Invest. 1991 Jul;65(1):104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh PK, Kumbhakar M, Pal H, Nath S. Ultrafast torsional dynamics of protein binding dye thioflavin-T in nanoconfined water pool. The journal of physical chemistry. 2009 Jun 25;113(25):8532–8538. doi: 10.1021/jp902207k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeVine H., 3rd Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid peptides: detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci. 1993 Mar;2(3):404–410. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeVine H., 3rd Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh PK, Kumbhakar M, Pal H, Nath S. Ultrafast bond twisting dynamics in amyloid fibril sensor. The journal of physical chemistry. 2010 Feb 25;114(7):2541–2546. doi: 10.1021/jp911544r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava A, Singh PK, Kumbhakar M, Mukherjee T, Chattopadyay S, Pal H, et al. Identifying the bond responsible for the fluorescence modulation in an amyloid fibril sensor. Chemistry. 2010 Aug 9;16(30):9257–9263. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockhart A, Ye L, Judd DB, Merritt AT, Lowe PN, Morgenstern JL, et al. Evidence for the presence of three distinct binding sites for the thioflavin T class of Alzheimer's disease PET imaging agents on beta-amyloid peptide fibrils. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005 Mar 4;280(9):7677–7684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye L, Morgenstern JL, Gee AD, Hong G, Brown J, Lockhart A. Delineation of positron emission tomography imaging agent binding sites on beta-amyloid peptide fibrils. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005 Jun 24;280(25):23599–23604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeVine H., 3rd Multiple ligand binding sites on A beta(1–40) fibrils. Amyloid. 2005 Mar;12(1):5–14. doi: 10.1080/13506120500032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Rodriguez C, Rimola A, Rodriguez-Santiago L, Ugliengo P, Alvarez-Larena A, Gutierrezde-Teran H, et al. Crystal structure of thioflavin-T and its binding to amyloid fibrils: insights at the molecular level. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010 Feb 21;46(7):1156–1158. doi: 10.1039/b912396b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C, Wang Z, Lei H, Duan Y, Bowers MT, Shea JE. The binding of thioflavin T and its neutral analog BTA-1 to protofibrils of the Alzheimer's disease Abeta(16–22) peptide probed by molecular dynamics simulations. J Mol Biol. 2008 Dec 19;384(3):718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C, Wang Z, Lei H, Zhang W, Duan Y. Dual binding modes of Congo red to amyloid protofibril surface observed in molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007 Feb 7;129(5):1225–1232. doi: 10.1021/ja0662772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dzwolak W, Pecul M. Chiral bias of amyloid fibrils revealed by the twisted conformation of Thioflavin T: an induced circular dichroism/DFT study. FEBS Lett. 2005 Dec 5;579(29):6601–6603. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biancalana M, Koide S. Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Jul;1804(7):1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biancalana M, Makabe K, Koide A, Koide S. Molecular mechanism of thioflavin-T binding to the surface of beta-rich peptide self-assemblies. J Mol Biol. 2009 Jan 30;385(4):1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu C, Biancalana M, Koide S, Shea JE. Binding modes of thioflavin-T to the single-layer beta-sheet of the peptide self-assembly mimics. J Mol Biol. 2009 Dec 11;394(4):627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groenning M, Norrman M, Flink JM, van de Weert M, Bukrinsky JT, Schluckebier G, et al. Binding mode of Thioflavin T in insulin amyloid fibrils. J Struct Biol. 2007 Sep;159(3):483–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groenning M. Binding mode of Thioflavin T and other molecular probes in the context of amyloid fibrils-current status. J Chem Biol. 2009 Aug 20; doi: 10.1007/s12154-009-0027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khurana R, Coleman C, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Carter SA, Krishna V, Grover RK, et al. Mechanism of thioflavin T binding to amyloid fibrils. J Struct Biol. 2005 Sep;151(3):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gellermann GP, Byrnes H, Striebinger A, Ullrich K, Mueller R, Hillen H, et al. Abeta-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008 May;30(2):212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, et al. Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Faseb J. 2005 Dec;19(14):2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, et al. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer's-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci. 2004 Nov 10;24(45):10191–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Tran L, Lambert MP, Glabe CG, Klein WL, et al. Temporal profile of amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomerization in an in vivo model of Alzheimer disease. A link between Abeta and tau pathology. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006 Jan 20;281(3):1599–1604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maezawa I, Hong HS, Liu R, Wu CY, Cheng RH, Kung MP, et al. Congo red and thioflavin-T analogs detect Abeta oligomers. Journal of neurochemistry. 2008 Jan;104(2):457–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan DA, Narrow WC, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ. An improved method for generating consistent soluble amyloid-beta oligomer preparations for in vitro neurotoxicity studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2010 Jul 15;190(2):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh DM, Hartley DM, Kusumoto Y, Fezoui Y, Condron MM, Lomakin A, et al. Amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. Structure and biological activity of protofibrillar intermediates. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999 Sep 3;274(36):25945–25952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemkul JA, Bevan DR. Assessing the stability of Alzheimer's amyloid protofibrils using molecular dynamics. The journal of physical chemistry. 2010 Feb 4;114(4):1652–1660. doi: 10.1021/jp9110794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jan A, Gokce O, Luthi-Carter R, Lashuel HA. The ratio of monomeric to aggregated forms of Abeta40 and Abeta42 is an important determinant of amyloid-beta aggregation, fibrillogenesis, and toxicity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008 Oct 17;283(42):28176–28189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803159200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi W, Zhang A, Patel D, Lee S, Harrington JL, Zhao L, et al. Simultaneous monitoring of peptide aggregate distributions, structure, and kinetics using amide hydrogen exchange: application to Abeta(1–40) fibrillogenesis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008 Aug 15;100(6):1214–1227. doi: 10.1002/bit.21846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Nuallain B, Shivaprasad S, Kheterpal I, Wetzel R. Thermodynamics of A beta(1–40) amyloid fibril elongation. Biochemistry. 2005 Sep 27;44(38):12709–12718. doi: 10.1021/bi050927h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shivaprasad S, Wetzel R. Scanning cysteine mutagenesis analysis of Abeta-(1–40) amyloid fibrils. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006 Jan 13;281(2):993–1000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klunk WE, Wang Y, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Holt DP, Mathis CA. Uncharged thioflavin-T derivatives bind to amyloid-beta protein with high affinity and readily enter the brain. Life Sci. 2001 Aug 17;69(13):1471–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhuang ZP, Kung MP, Hou C, Plossl K, Skovronsky D, Gur TL, et al. IBOX(2-(4'-dimethylaminophenyl)-6-iodobenzoxazole): a ligand for imaging amyloid plaques in the brain. Nucl Med Biol. 2001 Nov;28(8):887–894. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kung MP, Hou C, Zhuang ZP, Zhang B, Skovronsky D, Trojanowski JQ, et al. IMPY: an improved thioflavin-T derivative for in vivo labeling of beta-amyloid plaques. Brain Res. 2002 Nov 29;956(2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kung MP, Zhuang ZP, Hou C, Jin LW, Kung HF. Characterization of radioiodinated ligand binding to amyloid beta plaques. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20(3):249–254. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ono M, Kawashima H, Nonaka A, Kawai T, Haratake M, Mori H, et al. Novel benzofuran derivatives for PET imaging of beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease brains. J Med Chem. 2006 May 4;49(9):2725–2730. doi: 10.1021/jm051176k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee JH, Byeon SR, Lim SJ, Oh SJ, Moon DH, Yoo KH, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of stilbenylbenzoxazole and stilbenylbenzothiazole derivatives for detecting beta-amyloid fibrils. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2008 Feb 15;18(4):1534–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ono M, Hayashi S, Kimura H, Kawashima H, Nakayama M, Saji H. Push-pull benzothiazole derivatives as probes for detecting beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's brains. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2009 Oct 1;17(19):7002–7007. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cui MC, Li ZJ, Tang RK, Liu BL. Synthesis and evaluation of novel benzothiazole derivatives based on the bithiophene structure as potential radiotracers for beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2010 Apr 1;18(7):2777–2784. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhuang ZP, Kung MP, Hou C, Skovronsky DM, Gur TL, Plossl K, et al. Radioiodinated styrylbenzenes and thioflavins as probes for amyloid aggregates. J Med Chem. 2001 Jun 7;44(12):1905–1914. doi: 10.1021/jm010045q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin KS, Debnath ML, Mathis CA, Klunk WE. Synthesis and beta-amyloid binding properties of rhenium 2-phenylbenzothiazoles. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2009 Apr 15;19(8):2258–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, Mathis CA, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Holt DP, Shao L, et al. Effects of lipophilicity on the affinity and nonspecific binding of iodinated benzothiazole derivatives. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20(3):255–260. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mathis CA, Wang Y, Holt DP, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Klunk WE. Synthesis and evaluation of 11C-labeled 6-substituted 2-arylbenzothiazoles as amyloid imaging agents. J Med Chem. 2003 Jun 19;46(13):2740–2754. doi: 10.1021/jm030026b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howie AJ, Brewer DB. Optical properties of amyloid stained by Congo red: history and mechanisms. Micron. 2009 Apr;40(3):285–301. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howie AJ, Brewer DB, Howell D, Jones AP. Physical basis of colors seen in Congo red-stained amyloid in polarized light. Lab Invest. 2008 Mar;88(3):232–242. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klunk WE, Debnath ML, Pettegrew JW. Development of small molecule probes for the beta-amyloid protein of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1994 Nov–Dec;15(6):691–698. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma B, Nussinov R. Stabilities and conformations of Alzheimer's beta -amyloid peptide oligomers (Abeta 16–22, Abeta 16–35, and Abeta 10–35): Sequence effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 29;99(22):14126–14131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212206899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Childers WS, Mehta AK, Lu K, Lynn DG. Templating molecular arrays in amyloid's cross-beta grooves. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009 Jul 29;131(29):10165–10172. doi: 10.1021/ja902332s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hudson SA, Ecroyd H, Kee TW, Carver JA. The thioflavin T fluorescence assay for amyloid fibril detection can be biased by the presence of exogenous compounds. Febs J. 2009 Oct;276(20):5960–5972. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, et al. A structural model for Alzheimer's beta -amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Dec 24;99(26):16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keshet B, Gray JJ, Good TA. Structurally distinct toxicity inhibitors bind at common loci on beta-amyloid fibril. Protein Sci. 2010 Sep 29; doi: 10.1002/pro.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pedersen MO, Mikkelsen K, Behrens MA, Pedersen JS, Enghild JJ, Skrydstrup T, et al. NMR reveals two-step association of Congo Red to amyloid beta in low-molecular-weight aggregates. The journal of physical chemistry. 2010 Dec 9;114(48):16003–16010. doi: 10.1021/jp108035y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mathis CA, Wang Y, Klunk WE. Imaging beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the aging human brain. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(13):1469–1492. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reinke AA, Gestwicki JE. Structure-activity relationships of amyloid beta-aggregation inhibitors based on curcumin: influence of linker length and flexibility. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007 Sep;70(3):206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Styren SD, Hamilton RL, Styren GC, Klunk WE. X-34, a fluorescent derivative of Congo red: a novel histochemical stain for Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000 Sep;48(9):1223–1232. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skovronsky DM, Zhang B, Kung MP, Kung HF, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. In vivo detection of amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Jun 20;97(13):7609–7614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crystal AS, Giasson BI, Crowe A, Kung MP, Zhuang ZP, Trojanowski JQ, et al. A comparison of amyloid fibrillogenesis using the novel fluorescent compound K114. Journal of neurochemistry. 2003 Sep;86(6):1359–1368. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klunk WE, Bacskai BJ, Mathis CA, Kajdasz ST, McLellan ME, Frosch MP, et al. Imaging Abeta plaques in living transgenic mice with multiphoton microscopy and methoxy-X04, a systemically administered Congo red derivative. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002 Sep;61(9):797–805. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.9.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ortica F, Rodgers MA. A laser flash photolysis study of curcumin in dioxane-water mixtures. Photochem Photobiol. 2001 Dec;74(6):745–751. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0745:alfpso>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yanagisawa D, Shirai N, Amatsubo T, Taguchi H, Hirao K, Urushitani M, et al. Relationship between the tautomeric structures of curcumin derivatives and their Abeta-binding activities in the context of therapies for Alzheimer's disease. Biomaterials. 2010 May;31(14):4179–4185. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, et al. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005 Feb 18;280(7):5892–5901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tjernberg LO, Naslund J, Lindqvist F, Johansson J, Karlstrom AR, Thyberg J, et al. Arrest of beta-amyloid fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996 Apr 12;271(15):8545–8548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hilbich C, Kisters-Woike B, Reed J, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Substitutions of hydrophobic amino acids reduce the amyloidogenicity of Alzheimer's disease beta A4 peptides. J Mol Biol. 1992 Nov 20;228(2):460–473. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Esler WP, Stimson ER, Ghilardi JR, Lu YA, Felix AM, Vinters HV, et al. Point substitution in the central hydrophobic cluster of a human beta-amyloid congener disrupts peptide folding and abolishes plaque competence. Biochemistry. 1996 Nov 5;35(44):13914–13921. doi: 10.1021/bi961302+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bieschke J, Siegel SJ, Fu Y, Kelly JW. Alzheimer's Abeta peptides containing an isostructural backbone mutation afford distinct aggregate morphologies but analogous cytotoxicity. Evidence for a common low-abundance toxic structure(s)? Biochemistry. 2008 Jan 8;47(1):50–59. doi: 10.1021/bi701757v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cerf E, Sarroukh R, Tamamizu-Kato S, Breydo L, Derclaye S, Dufrene YF, et al. Antiparallel beta- sheet: a signature structure of the oligomeric amyloid beta-peptide. Biochem J. 2009 Aug 1;421(3):415–423. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu L, Edalji R, Harlan JE, Holzman TF, Lopez AP, Labkovsky B, et al. Structural characterization of a soluble amyloid beta-peptide oligomer. Biochemistry. 2009 Mar 10;48(9):1870–1877. doi: 10.1021/bi802046n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hwang W, Zhang S, Kamm RD, Karplus M. Kinetic control of dimer structure formation in amyloid fibrillogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Aug 31;101(35):12916–12921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402634101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gnanakaran S, Nussinov R, Garcia AE. Atomic-level description of amyloid beta-dimer formation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006 Feb 22;128(7):2158–2159. doi: 10.1021/ja0548337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tjernberg LO, Lilliehook C, Callaway DJ, Naslund J, Hahne S, Thyberg J, et al. Controlling amyloid beta-peptide fibril formation with protease-stable ligands. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997 May 9;272(19):12601–12605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Watanabe K, Segawa T, Nakamura K, Kodaka M, Konakahara T, Okuno H. Identification of the molecular interaction site of amyloid beta peptide by using a fluorescence assay. J Pept Res. 2001 Oct;58(4):342–346. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2001.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang A, Qi W, Good TA, Fernandez EJ. Structural differences between Abeta(1–40) intermediate oligomers and fibrils elucidated by proteolytic fragmentation and hydrogen/deuterium exchange. Biophysical journal. 2009 Feb;96(3):1091–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olofsson A, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Ohman A. The solvent protection of alzheimer amyloid-beta-(1–42) fibrils as determined by solution NMR spectroscopy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006 Jan 6;281(1):477–483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cairo CW, Strzelec A, Murphy RM, Kiessling LL. Affinity-based inhibition of beta-amyloid toxicity. Biochemistry. 2002 Jul 9;41(27):8620–8629. doi: 10.1021/bi0156254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chalifour RJ, McLaughlin RW, Lavoie L, Morissette C, Tremblay N, Boule M, et al. Stereoselective interactions of peptide inhibitors with the beta-amyloid peptide. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003 Sep 12;278(37):34874–34881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ouberai M, Dumy P, Chierici S, Garcia J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of clicked curcumin and clicked KLVFFA conjugates as inhibitors of beta-amyloid fibril formation. Bioconjug Chem. 2009 Nov;20(11):2123–2132. doi: 10.1021/bc900281b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang G, Leibowitz MJ, Sinko PJ, Stein S. Multiple-peptide conjugates for binding beta-amyloid plaques of Alzheimer's disease. Bioconjug Chem. 2003 Jan–Feb;14(1):86–92. doi: 10.1021/bc025526i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gordon DJ, Meredith SC. Probing the role of backbone hydrogen bonding in beta-amyloid fibrils with inhibitor peptides containing ester bonds at alternate positions. Biochemistry. 2003 Jan 21;42(2):475–485. doi: 10.1021/bi0259857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gordon DJ, Sciarretta KL, Meredith SC. Inhibition of beta-amyloid(40) fibrillogenesis and disassembly of beta-amyloid(40) fibrils by short beta-amyloid congeners containing N-methyl amino acids at alternate residues. Biochemistry. 2001 Jul 27;40(28):8237–8245. doi: 10.1021/bi002416v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gordon DJ, Tappe R, Meredith SC. Design and characterization of a membrane permeable N-methyl amino acid-containing peptide that inhibits Abeta1-40 fibrillogenesis. J Pept Res. 2002 Jul;60(1):37–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2002.11002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Findeis MA, Musso GM, Arico-Muendel CC, Benjamin HW, Hundal AM, Lee JJ, et al. Modified- peptide inhibitors of amyloid beta-peptide polymerization. Biochemistry. 1999 May 25;38(21):6791–6800. doi: 10.1021/bi982824n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, et al. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomers to fibrils. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2010 May;17(5):561–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chimon S, Shaibat MA, Jones CR, Calero DC, Aizezi B, Ishii Y. Evidence of fibril-like beta-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2007 Dec 2; doi: 10.1038/nsmb1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yagi H, Ban T, Morigaki K, Naiki H, Goto Y. Visualization and classification of amyloid beta supramolecular assemblies. Biochemistry. 2007 Dec 25;46(51):15009–15017. doi: 10.1021/bi701842n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mastrangelo IA, Ahmed M, Sato T, Liu W, Wang C, Hough P, et al. High-resolution atomic force microscopy of soluble Abeta42 oligomers. Journal of molecular biology. 2006 Apr 21;358(1):106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhu M, Han S, Zhou F, Carter SA, Fink AL. Annular oligomeric amyloid intermediates observed by in situ atomic force microscopy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004 Jun 4;279(23):24452–24459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kheterpal I, Zhou S, Cook KD, Wetzel R. Abeta amyloid fibrils possess a core structure highly resistant to hydrogen exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000 Dec 5;97(25):13597–13601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250288897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sarroukh R, Cerf E, Derclaye S, Dufrene YF, Goormaghtigh E, Ruysschaert JM, et al. Transformation of amyloid beta(1–40) oligomers into fibrils is characterized by a major change in secondary structure. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010 Sep 19; doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0529-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reinke AA, Seh HY, Gestwicki JE. A chemical screening approach reveals that indole fluorescence is quenched by pre-fibrillar but not fibrillar amyloid-beta. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2009 Sep 1;19(17):4952–4957. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Necula M, Breydo L, Milton S, Kayed R, van der Veer WE, Tone P, et al. Methylene blue inhibits amyloid Abeta oligomerization by promoting fibrillization. Biochemistry. 2007 Jul 31;46(30):8850–8860. doi: 10.1021/bi700411k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Necula M, Kayed R, Milton S, Glabe CG. Small molecule inhibitors of aggregation indicate that amyloid beta oligomerization and fibrillization pathways are independent and distinct. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007 Apr 6;282(14):10311–10324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Convertino M, Pellarin R, Catto M, Carotti A, Caflisch A. 9,10-Anthraquinone hinders beta-aggregation: how does a small molecule interfere with Abeta-peptide amyloid fibrillation? Protein Sci. 2009 Apr;18(4):792–800. doi: 10.1002/pro.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maezawa I, Hong HS, Wu HC, Battina SK, Rana S, Iwamoto T, et al. A novel tricyclic pyrone compound ameliorates cell death associated with intracellular amyloid-beta oligomeric complexes. Journal of neurochemistry. 2006 Jul;98(1):57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Aslund A, Herland A, Hammarstrom P, Nilsson KP, Jonsson BH, Inganas O, et al. Studies of luminescent conjugated polythiophene derivatives: enhanced spectral discrimination of protein conformational states. Bioconjug Chem. 2007 Nov–Dec;18(6):1860–1868. doi: 10.1021/bc700180g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aslund A, Sigurdson CJ, Klingstedt T, Grathwohl S, Bolmont T, Dickstein DL, et al. Novel pentameric thiophene derivatives for in vitro and in vivo optical imaging of a plethora of protein aggregates in cerebral amyloidoses. ACS Chem Biol. 2009 Aug 21;4(8):673–684. doi: 10.1021/cb900112v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hammarstrom P, Simon R, Nystrom S, Konradsson P, Aslund A, Nilsson KP. A fluorescent pentameric thiophene derivative detects in vitro-formed prefibrillar protein aggregates. Biochemistry. 2010 Aug 17;49(32):6838–6845. doi: 10.1021/bi100922r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nilsson KP, Aslund A, Berg I, Nystrom S, Konradsson P, Herland A, et al. Imaging distinct conformational states of amyloid-beta fibrils in Alzheimer's disease using novel luminescent probes. ACS Chem Biol. 2007 Aug 17;2(8):553–560. doi: 10.1021/cb700116u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nilsson KP, Ikenberg K, Aslund A, Fransson S, Konradsson P, Rocken C, et al. Structural typing of systemic amyloidoses by luminescent-conjugated polymer spectroscopy. Am J Pathol. 2010 Feb;176(2):563–574. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.080797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reinke AA, Abulwerdi GA, Gestwicki JE. Quantifying prefibrillar amyloids in vitro by using a "thioflavin-like" spectroscopic method. Chembiochem. 2010 Sep 3;11(13):1889–1895. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hu Y, Su B, Kim CS, Hernandez M, Rostagno A, Ghiso J, et al. A Strategy for Designing a Peptide Probe for Detection of beta-Amyloid Oligomers. Chembiochem. 2010 Oct 28; doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Reinke AA, Ung PM, Quintero JJ, Carlson HA, Gestwicki JE. Chemical Probes That Selectively Recognize the Earliest Abeta Oligomers in Complex Mixtures. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010 Nov 24; doi: 10.1021/ja106291e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shi W, Dolai S, Rizk S, Hussain A, Tariq H, Averick S, et al. Synthesis of monofunctional curcumin derivatives, clicked curcumin dimer, and a PAMAM dendrimer curcumin conjugate for therapeutic applications. Org Lett. 2007 Dec 20;9(26):5461–5464. doi: 10.1021/ol702370m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lenhart JA, Ling X, Gandhi R, Guo TL, Gerk PM, Brunzell DH, et al. "Clicked" bivalent ligands containing curcumin and cholesterol as multifunctional abeta oligomerization inhibitors: design, synthesis, and biological characterization. J Med Chem. 2010 Aug 26;53(16):6198–6209. doi: 10.1021/jm100601q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Qin L, Vastl J, Gao J. Highly sensitive amyloid detection enabled by thioflavin T dimers. Molecular bioSystems. 2010 Oct 1;6(10):1791–1795. doi: 10.1039/c005255h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chafekar SM, Malda H, Merkx M, Meijer EW, Viertl D, Lashuel HA. Branched KLVFF tetramers strongly potentiate inhibition of beta-amyloid aggregation. Chembiochem. 2007 Oct 15;8(15):1857–1864. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]