Abstract

Background

Although pancreatic rests have characteristic endoscopic features, confirming a histological diagnosis may be desirable to exclude other significant pathology.

Aims

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy (EBLSP) for removal of suspected pancreatic rests and to compare the diagnostic yield to other endoscopic tissue sampling methods.

Methods

An electronic endoscopic report database was searched for patients referred for evaluation of incidentally found gastric antral subepithelial lesions. Tissue sampling technique, pathology, and complications were recorded.

Results

Removal of suspected pancreatic rests with EBLSP was successful in all 21 cases without complications. Nineteen of 21 (90%) who underwent EBLSP had a histological diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas compared with 5 of 14 (36%) who underwent tissue sampling with biopsy and/or snare (P = 0.001). The endoscopic characteristics of the histology proven pancreatic rests were an antral subepithelial mass with central umbilication measuring 6–10 mm in diameter and located 2–6 cm from the pylorus in the 3–7 o’clock position.

Conclusions

Endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy resection of gastric antral lesions suspected to be pancreatic rests had a diagnostic yield superior to standard biopsy forceps and snare polypectomy techniques. However, because all pathologically confirmed pancreatic rests had typical endoscopic appearances of pancreatic rests, it may not be necessary to obtain histologic diagnosis for every suspected gastric antral heterotopic pancreas.

Keywords: Pancreatic rest, Pancreatic heterotopia, Ectopic pancreas, Heterotopic pancreas, Subepithelial mass, Endoscopic mucosal resection

Introduction

Pancreatic rests are benign congenital anomalies defined as pancreatic tissue that lacks anatomic or vascular continuity with the pancreas itself [1]. Also referred to as pancreatic heterotopia, heterotopic pancreas, ectopic pancreas, aberrant pancreas, and accessory pancreas, pancreatic rests have been found in up to 0.5–13% of autopsies and in 1 out of every 500 upper abdominal operations [2–4]. Although they can be located in many sites throughout the body, they are most commonly found in the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the gastric antrum being the most common site [5]. The endoscopic appearance of gastric pancreatic rests has been described as a smooth or umbilicated submucosal nodule, 0.6–3 cm in diameter, located within 3–6 cm of the pylorus [4–7]. In the majority of patients, pancreatic rests are asymptomatic and are found incidentally during routine endoscopic or radiographic evaluation. In rare cases, they can present with dyspepsia, ectopic pancreatitis, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, gastric outlet obstruction, and even malignant degeneration [8, 9].

The differential diagnosis of gastric antral subepithelial lesions includes benign entities such as pancreatic rests, lipomas, inflammatory polyps, hyperplastic mucosa, and cysts as well as entities with malignant potential such as carcinoid tumors and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Therefore, tissue sampling to obtain a histological diagnosis may be beneficial in excluding more serious entities. Due to the subepithelial location of pancreatic rests, obtaining a histological diagnosis and resection can be challenging using standard endoscopic techniques. Standard forceps biopsy or snare polypectomy is often non-diagnostic due to inadequate depth of sampling. This has led to small case reports of the use of cap-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection and ligation assisted endoscopic mucosal resection of gastric heterotopia [6, 7]. This is the first large case series to evaluate the efficacy and safety of removal of suspected gastric antral pancreatic rests with endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy (EBLSP) technique.

Methods

An electronic endoscopic report database was searched for patients who were referred to an academic medical center for upper endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound for evaluation of gastric antral subepithelial lesions between January 2000 and January 2010. All procedures were performed by a single endoscopist. Endoscopy reports were reviewed for the endoscopic appearance of pancreatic rests, as defined by smooth or umbilicated subepithelial masses measuring up to 3 cm diameter and located within 6 cm of the pylorus in the gastric antrum. Tissue sampling technique and final pathology results were recorded. Charts were reviewed and patients and referring physicians were contacted via telephone to determine if complications occurred. Statistical analysis was performed with Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables. This retrospective study was approved by the University of California San Diego Human Research Protection Program.

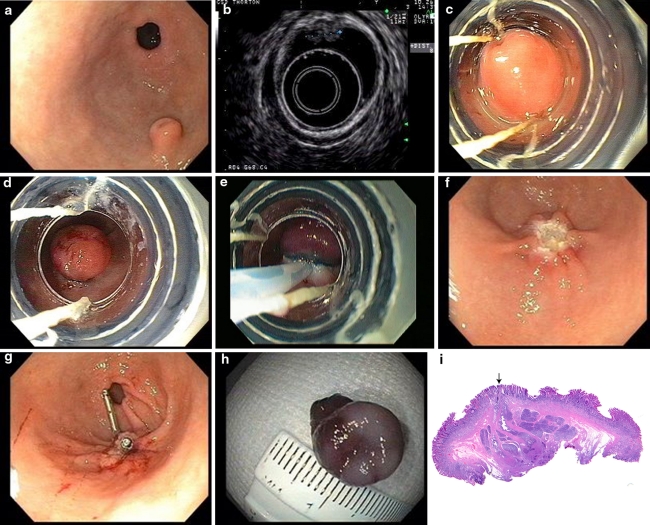

All procedures were performed with the patient under moderate sedation. Standard video-endoscopes and electronic radial echoendoscopes were used (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). The tissue sampling method was performed at the discretion of the endoscopist. Between January 2000 and January 2008 sampling was performed with either jumbo biopsy forceps or snare polypectomy. After January 2008, all sampling was performed using endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy. The endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy technique was performed with a forward viewing upper endoscope fitted with a band ligation cap (Cook Duett® DT-6 Multi-Band Mucosectomy cap, Cook Medical Inc, Bloomington, IN) (Fig. 1a–i). The lesion was first identified with video endoscopy (Fig. 1a), and then endoscopic ultrasound using a radial echoendoscope was performed to make sure the lesion was limited to the mucosal/submucosal layer (Fig. 1b). The lesion was aspirated into the cap (Fig. 1c) and a trip wire was used to deploy the band off the cap to ligate the lesion (Fig. 1d). A hexagonal snare with a braided wire (Mini-Hex Snare, Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN) was placed around the created polypoid ligated lesion, and the snare was tightened below the band. The snare was moved gently back and forth in order to ensure separation between the submucosa and muscularis propria. Snare polypectomy of the lesion was performed with cautery current (Fig. 1e). The lesion was then suctioned into the cap and removed through the mouth. The endoscope was reinserted to examine the defect (Fig. 1f). Depending upon the size of the defect, endoscopic clips (Resolution Clips, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA or QuickClip2, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) were placed to close the residual defect (Fig. 1g). The specimen (Fig. 1h) was then mounted on cardboard with string and sent for pathologic evaluation (Fig. 1i).

Fig. 1.

a Endoscopic appearance of a pancreatic rest. Note the lesion is a subepithelial umbilicated lesion in 5 o’clock position located 3 cm from the pylorus with normal overlying mucosa. b Endoscopic ultrasound showing heterogenous lesion located in the submucosal layer. c Pancreatic rest is aspirated into cap. d Rubber band ligates pancreatic rest. e Snare polypectomy of pancreatic rest is performed. f Mucosal defect resulting from snare polypectomy of the pancreatic rest. g Mucosal defect is closed with clips. h Specimen is mounted prior to sending to pathology. Diameter of specimen is approximately 10 mm. i Low power view of a representative cross section of a gastric antral pancreatic rest. Note the dome shaped contour with a centrally located duct, draining onto the mucosal surface (arrow). The pancreatic rest is located in the submucosa and consists of rounded lobules of pancreatic acinar tissue with associated ducts

Results

A total of 35 patients were identified that underwent tissue sampling of a gastric antral subepithelial lesion with the endoscopic appearance of a pancreatic rest. All of these lesions were incidental findings by referring gastroenterologists who performed endoscopy for other reasons and felt these were not causing symptoms.

Tissue sampling of these 35 suspected pancreatic rests was performed with EBLSP in 21 cases, and with biopsy forceps and/or snare polypectomy techniques in 14 cases. The overall pathologic findings revealed 24 (69%) pancreatic rests, three (9%) foveolar hyperplasia, three (9%) normal gastric mucosa, two (6%) inflamed gastric mucosa, two (6%) fibroid polyp, and one (3%) leiomyoma. Table 1 shows the pathology of the 21 lesions removed with EBLSP revealing 19 pancreatic rests, one leiomyoma, and one inflamed fibroid polyp. For the 14 patients with suspected PRs who had tissue sampling performed with biopsy forceps and/or snare polypectomy techniques a histological diagnosis of pancreatic rest was diagnosed in only five patients (36% versus 90% with EBLSP, P = 0.001), with the majority yielding benign mucosa in eight patients (57% vs. 0% with EBLSP, P = 0.004). Tissue sampling of six suspected pancreatic rests with biopsy forceps diagnosed one pancreatic rest (17%) and five benign mucosa (83%) (2 normal mucosa, 2 inflamed mucosa, and 1 foveolar hyperplasia). Snare polypectomy of five suspected pancreatic rests diagnosed two pancreatic rests (40%), one inflamed fibroid polyp, and two benign mucosa (40%; 2 foveolar hyperplasia). Saline assisted snare polypectomy of two suspected pancreatic rests diagnosed one pancreatic rest (50%) and one benign mucosa (50%). Snare polypectomy followed by multiple forceps biopsies of the base was performed on one suspected pancreatic rest confirming a histological diagnosis of PR (100%). There were no complications observed in any of the cases based on chart review and follow-up telephone communication with patients and referring physicians.

Table 1.

Histological diagnosis of suspected pancreatic rests by tissue sampling technique

| Histological diagnosis | EBLSP (n = 21) | Biopsy and/or snarea (n = 14) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic rest | 19 (90%) | 5 (36%) | 0.001 |

| Leiomyoma | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | NS |

| Fibroid polyp | 1 (5%) | 1 (7%) | NS |

| Benign mucosab | 0 (0%) | 8 (57%) | 0.004 |

EBLSP endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy

aBiopsy forceps alone (n = 6), snare polypectomy (n = 5), saline assisted snare polypectomy (n = 2), and snare polypectomy followed by biopsy forceps of the base (n = 1)

bBenign mucosa includes normal gastric mucosa (n = 3), inflamed gastric mucosa (n = 2), and foveolar hyperplasia (n = 3)

The clinical characteristics of patients with histology proven pancreatic rests resected using the EBLSP technique are shown in Table 2. The median age of patients with histology proven pancreatic rests diagnosed by EBLSP was 53 years (range 28–89 years), with 58% being female. The median endoscopic size of pancreatic rests diagnosed by EBLSP was 10 mm (range 6–10 mm). Pancreatic rests diagnosed by EBLSP were located at a median distance from the pylorus of 3 cm (range 2–6 cm) and the median clock position relative to the pylorus was 5 o’clock (range 3–7 o’clock). Eleven pancreatic rests diagnosed by EBLSP (58%) were noted to have central umbilication. Seventeen of 19 patients (89%) with histology proven pancreatic rests by EBLSP underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). The mean endosonographic dimensions of pancreatic rests diagnosed by EBLSP were 7 mm by 4 mm, with an EUS appearance of hypoechoic or heterogeneous lesions located in the submucosal layer. In two cases no EUS was performed before EBLSP because of lack of available EUS equipment and very superficial appearance of the gastric antral lesion by videoendoscopy.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with histology proven pancreatic rests resected with EBLSP technique

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 53 years (range 28–89) |

| Sex (female/male) | 11 female/8 male |

| Median endoscopic size of lesion (mm) | 10 mm (range 6–10) |

| EUS size of lesion (mean long axis by short axis in mm) | 7 mm × 4 mm |

| Median distance of lesion from the pylorus (cm) | 3 cm (range 2–6) |

| Clock position of lesion relative to pylorus (o’clock) | 5 o’clock (range 3–7) |

| Umbilicated endoscopic appearance (n) | 11 (58%) |

EBLSP endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy, EUS endoscopic ultrasound

Discussion

This case series shows that asymptomatic incidentally found gastric antral subepithelial masses which have the endoscopic appearance of pancreatic rests can effectively and safely be removed using endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy technique. Of the lesions removed with EBLSP, 90% had a histological diagnosis of pancreatic rest compared to only 36% (P = 0.001) of lesions removed with biopsy and/or snare techniques. There were no serious pathologic lesions found in any of the non-pancreatic rest resection specimens.

A study by Cantor et al. [10] found that cap-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection of histology proven pancreatic rests gave a higher diagnostic yield than forceps biopsy alone (83% vs. 17%). The diagnostic yield of EBLSP for suspected pancreatic rests in our study (90%) was similar to that study, as would be expected as both used similar cap-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection techniques.

Other studies have also shown that obtaining a tissue diagnosis of pancreatic rests with standard forceps biopsy has a low diagnostic yield of 0–40% [3, 11, 12]. This is due to the superficial nature of forceps biopsy which samples the mucosa while pancreatic rests are located deeper in the submucosal layer. Our study had a similar low 36% rate of diagnostic yield for pancreatic rests using biopsy forceps and/or snare polypectomy techniques.

The appearance of gastric antral pancreatic rests in our study corresponds to that which has been described previously [6, 7]. We would add that in all cases, gastric antral pancreatic rests were found along the greater curvature posterior wall of the stomach in the endoscopic 3–7 o’clock position (median 5 o’clock) relative to the pylorus. This makes sense anatomically as this is the area of the stomach that is in closest proximity to the pancreas.

In all cases of histology proven pancreatic rests, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed hypoechoic, heterogeneous lesions involving the submucosal layer. This is consistent with previous reports describing the endosonographic features of pancreatic rests [2, 6, 7, 13]. EUS is helpful in further characterizing the lesion and excluding other lesions such as lipomas, cysts, stromal tumors, and extrinsic compression. EUS should be performed prior to endoscopic mucosal resection to ensure safety of resection by making sure the lesion is superficial, not vascular, and does not involve the muscularis propria.

There are several methodologic limitations of this study. It was a retrospective study which compared patients who were referred for EGD and EUS of gastric subepithelial lesions during which the initial time period we used biopsies and snare polypectomy for tissue sampling and a later time period we used endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy. A prospective randomized study would be better for comparing the two techniques. Another limitation is that follow-up endoscopies were not performed to assess for complete histologic removal of the lesion, although given that they were all benign lesions it was not felt that further repeat follow-up endoscopy was needed. This series was also too small to determine the exact incidence of rare lesions which might have more concerning pathology such as carcinoid tumors or gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

Regarding the safety of either band ligation snare polypectomy or cap suction endoscopic mucosal resection, it is important to note that it is likely safer to perform resection of lesions in the antrum where the muscle layer is thicker than in the proximal stomach which is thinner and may have an increased risk of perforation. This series was too small to identify the exact risks of endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy in the gastric antrum.

It is important to note that these study results do not imply that all suspected gastric antral lesions which appear to be pancreatic rests require endoscopic resection for tissue confirmation. The fact that all of the histologically confirmed pancreatic rests had a similar endoscopic appearance (antral subepithelial lesion located in the gastric antrum, 2–6 cm from the pylorus, in the 3–7 o’clock position, with possible central umbilication, and EUS characteristics of a subcentimeter lesion in the mucosa/submucosal layer) suggests that lesions with the typical endoscopic appearance of a pancreatic rest may not require tissue sampling and usually can be assumed to be a pancreatic rest. Mucosal biopsies can exclude epithelial tumors, and EUS can help exclude other lesions (such as cysts, lipomas, stromal tumors, or extrinsic lesions). Each case should be individualized as to whether tissue sampling is needed in cases of suspected gastric antral heterotopic pancreas as there are potential risks associated with routine resection of gastric lesions.

In conclusion, resection of gastric antral pancreatic rests by endoscopic band ligation snare polypectomy technique appears to be a safe and effective method of confirming a histological diagnosis and may provide a superior diagnostic yield than standard tissue sampling techniques. However, because all pathologically confirmed pancreatic rests had typical endoscopic appearances of pancreatic rests, it may not be necessary to routinely obtain histologic diagnosis for every suspected gastric antral heterotopic pancreas.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, et al. Anatomy, histology, embryology, and developmental anomalies of the pancreas. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease, vol 1. 8. Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2006. pp. 1183–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen SH, Huang WH, Feng CL, et al. Clinical analysis of ectopic pancreas with endoscopic ultrasonography: an experience in a medical center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:877–881. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ormarsson OT, Gudmundsdottir I, Marvik R. Diagnosis and treatment of gastric heterotopic pancreas. World J Surg. 2006;30:1682–1689. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbosa de Castro JJ, Dockerty MB, Waugh JM. Pancreatic heterotopia: review of the literature and report of 41 authenticated surgical cases, of which 25 were clinically significant. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1946;82:527–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer ED. Benign intramural tumors of stomach. Medicine. 1951;30:83–96. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faigel DO, Gopal D, Weks DA, et al. Cap-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection of a pancreatic rest. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:782–784. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khashab MA, Cummings OW, DeWitt JM. Ligation–assisted endoscopic mucosal resection of gastric heterotopic pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2805–2808. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubbia-Brandt L, Huber O, Hadengue A, et al. An unusual case of gastric heterotopic pancreas. JOP. 2004;5:484–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaib Y, Rabaa E, Feddersen R, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to heterotopic pancreas in the antrum: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:527–530. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantor MJ, Davila RE, Faigel DO. Yield of tissue sampling for subepithelial lesions evaluated by EUS: a comparison between forceps biopsies and endoscopic submucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai ECS, Tomkins RK. Heterotopic pancreas: review of a 26 year experience. Am J Surg. 1986;151:697–700. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsai C-Y, Wu C-W, Lui W-Y. Heterotopic pancreas: a difficult diagnosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:144–147. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199903000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Okazaki K, et al. Gastric aberrant pancreas: EUS analysis in comparison with the histology. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:493–497. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]