Abstract

There is increasing interest in the J-PRESS technique, an in vivo implementation of two-dimensional J-spectroscopy combined with PRESS localization, for high field spectroscopy studies of the human brain. The experiment is designed to resolve scalar couplings in the 2nd, indirectly detected dimension, but will only do so if the slice-selective refocusing pulses in the PRESS sequence affect all coupled spins equally. At high magnet field strengths, due to limited RF pulse bandwidth, PRESS-based localization results in spatially dependent evolution of coupling. In some regions of the localized volume, coupling evolves during the PRESS echo time, while in other regions it may be partially or fully refocused. This study investigates the impact of this effect on the appearance of the J-PRESS spectrum for coupled spins, focusing on two commonly observed metabolites, lactate and N-acetyl aspartate, showing that such behavior results in additional peaks in the J-resolved spectrum (termed J-refocused peaks). It is also demonstrated that increasing the bandwidth of refocusing pulses significantly reduces the size of such signals.

Introduction

Conventional in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain suffers from limited resolution of metabolite signals along the chemical shift axis. Three main approaches have been used to reduce overlap of signals: the apparent width of multiplets can be reduced by moving to higher field; the number of signals displayed in the chemical shift dimension can be reduced by spectral editing methods; or the full spectrum can be spread into an additional dimension using two-dimensional acquisition methods. In the two-dimensional J-PRESS experiment (1), the localized in vivo implementation of J-resolved spectroscopy, signals in the spectrum that are split due to scalar (J-)couplings are skewed into the second dimension, potentially allowing overlapping multiplets with different chemical shift to be resolved from each other. Two-dimensional fitting of the J-resolved spectra has been implemented and shown to give improved measurement of metabolite concentrations compared to conventional PRESS spectra (2,3).

The J-PRESS experiment is implemented as a time series of PRESS experiments with incremented TE, where TE is treated as the indirectly acquired time dimension t1. Within the echo time of a PRESS experiment, evolution of the chemical shift offset is refocused, whereas the J-couplings continue to evolve. Thus, only coupling modulates the evolution of signals in t1, and Fourier transformation (FT) with respect to t1 yields an F1 dimension that only displays coupling information. During the acquisition time t2, both coupling and chemical shift offset evolve, and FT of the t2 dimension gives an F2 dimension which displays both chemical shift and coupling information. This results in multiplets that are arranged at a 45° angle to F1 = 0, while uncoupled signals lie on F1 = 0.

The PRESS experiment contains two slice-selective refocusing pulses, which localize two of the three dimensions of the excited voxel. The bandwidth of typical slice-selective pulses in vivo is limited by the maximum B1 field strength available, and there is usually a significant chemical shift displacement at B0 fields of 3T and above. For weakly coupled spin systems, this results in spatially dependent evolution of coupling within the PRESS voxel, as has been widely reported (4–10). This paper discusses the impact of the spatially dependent evolution of coupling on the intensity and appearance of coupled signals in the J-PRESS spectrum, and demonstrates the reduction of such effects by the implementation of high-bandwidth refocusing pulses.

Methods

Simulations and the Two-Compartment Model

The four-compartment model (10) is a useful simplification in considering the evolution of coupling during PRESS-based experiments. The PRESS-excited volume for the observed spin can be broken down into four compartments, in which the coupling partner experiences: both slice-selective pulses, the first pulse only, the second pulse only, or neither slice-selective refocusing pulse. Since the evolution of coupling is refocused by a spin echo in which only one coupling partner experiences the refocusing pulse, the phase characteristics of the two coupled signals are different in each compartment.

In the J-PRESS experiment, TE is usually incremented by shifting the second refocusing pulse, keeping the first spin echo as short as possible. A two-compartment model which only considers the effects of the second refocusing pulse was therefore used to describe the spatially dependent t1 modulations in J-PRESS. It is useful to define the quantity δ as:

| [1] |

where ΔΩ is the chemical shift difference between coupled spins and BW is the refocusing pulse bandwidth (both in Hz).

Idealized time-domain dataset were simulated in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick MA) for the lactate methyl resonance using the following equations:

Compartment I: passive spin does undergo refocusing pulse

| [2] |

Compartment II: passive spin does not undergo refocusing pulse

| [3] |

where T2 and T2* are the transverse relaxation times during t1 and t2.

Similarly, for the NAA aspartate CH2 signals:

Compartment I: passive spin does undergo refocusing pulse

| [4] |

Compartment II: passive spin does not undergo refocusing pulse

| [5] |

where J12 is the geminal coupling constant, J13 and J23 the vicinal coupling constants and ω is the chemical shift difference between the aspartate CH2 spins (Figure 1f). Fourier transformation with respect to t1 and t2 yielded two-dimensional spectra1.

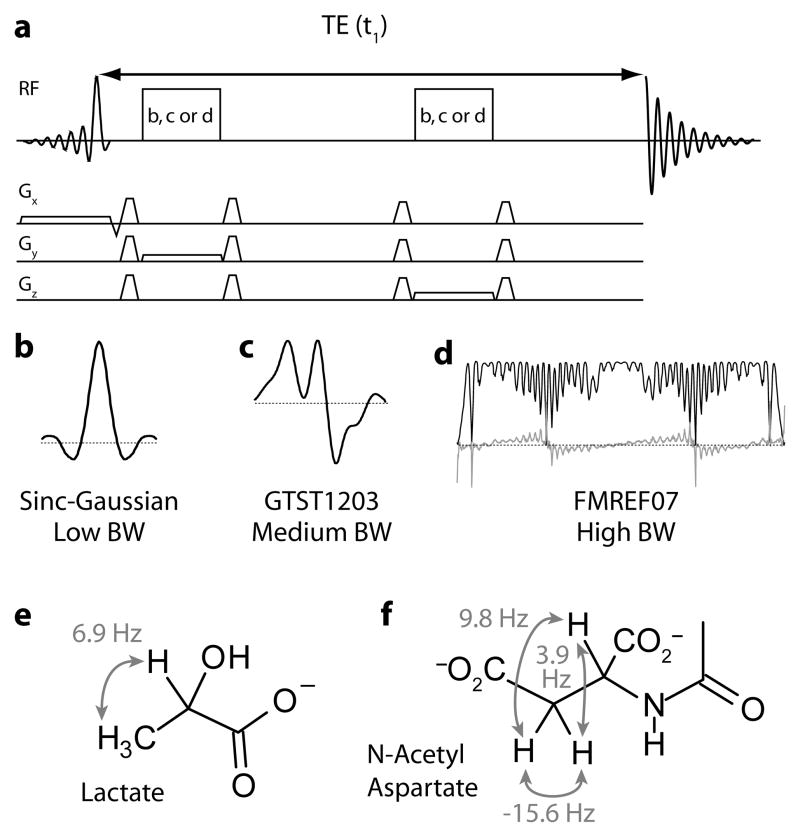

Figure 1.

Experimental Details. (a) Pulse sequence of J-PRESS. Delays either side of the second refocusing pulse are incremented to increment t1. The refocusing pulse shape is either (b), (c) or (d). (b) Amplitude modulation of low-bandwidth sinc-Gaussian refocusing pulse. (c) Amplitude modulation of medium-bandwidth GTST1203 refocusing pulse. (d) Amplitude (black) and frequency (gray) modulations of FMREF07 high-bandwidth refocusing pulse. Structure and relevant couplings of (e) lactate and (f) N-acetyl aspartate (NAA).

Under the two-compartment model, it is anticipated that Compartment I accounts for a fraction (1−δ) of the voxel and Compartment II accounts for a fraction δ.

3T MR experiments

J-PRESS experiments were performed on a Philips Achieva 3T scanner, using the body coil for transmit (B1max = 13.5 μT) and an eight-channel phased array head coil for receive, in a locally made phantom containing metabolites at concentrations typical of healthy brain (N-acetyl aspartate 12 mM, creatine 10 mM, choline 3.7 mM, myoinositol 7.5 mM, glutmate 12.5 mM, pH 7.1) with the addition of lactate at 5 mmol/dm3. 2048 datapoints across a 3 kHz spectral width were acquired in the directly acquired (t2) dimension. Three different refocusing pulses were used (Figure 1 (11)); a standard sinc-gauss pulse, an numerically-optimized amplitude modulated pulse called ‘GTST1203’, and a numerically-optimized frequency modulated pulse called ‘FMREF07’. The duration and bandwidth of slice-selective refocusing pulses were: sinc-gauss (echo 2) 6 ms, 733 Hz; GTST1203 (11) 6.9 ms, 1264 Hz; frequency-modulated (fmref07 (11–13)))) 17 ms, 2148 Hz. VAPOR water suppression (14) was applied and a repetition time (TR) of 2 s was used. 32 increments of TE between 32 ms and 528 ms were acquired (δTE = 16 ms) for low- and medium-bandwidth refocusing pulses. These parameters result in spectral width in F1 of 31 Hz and inherent resolution of 1 Hz/pt prior to 8-fold zero-filling in F1. The longer duration of the frequency-modulated pulses necessitated a minimum TE of 64 ms (leading to a maximum of 560 ms). The J-PRESS pulse sequence diagram is shown in Figure 1a and the amplitude and frequency modulations of the slice-selective refocusing pulses are shown in Figure 1b–d.

7T MR experiments

J-PRESS experiments were performed on a Philips Achieva 7T scanner, using a dedicated head coil for transmit (B1max = 12 μT) and a 32-channel phased array head coil for receive, in a second locally made phantom containing metabolites at concentrations typical of healthy brain with the addition of lactate at 5 mmol/dm3 and GABA at 5 mmol/dm3. 2048 datapoints across a 3 kHz spectral width were acquired in the directly acquired (t2) dimension. The GTST1203 pulse (11) was used for slice-selective refocusing pulses, duration and bandwidth of 7.8 ms and1123 Hz. VAPOR water suppression (14) was applied and a repetition time (TR) of 3s was used. 32 increments of TE between 40 ms and 660 ms were acquired (δTE = 20 ms). These parameters result in spectral width in F1 of 50 Hz and inherent resolution of 1.6 Hz/pt prior to 8-fold zero-filling in F1.

Results

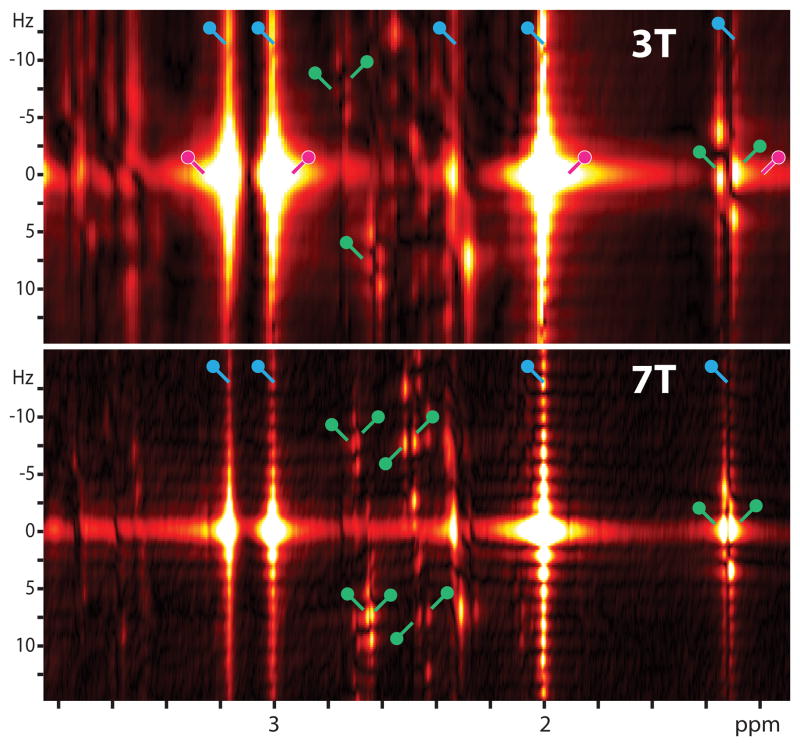

Figure 2 compares J-PRESS spectra acquired at 3T (a) and 7T (b). Several J-resolved signals can be seen in both spectra. Considering the lactate signal at 1.3 ppm, it can clearly be seen in both spectra that, in addition to the intended J-resolved peaks at F1 = ±3.5 Hz, there are additional signals at F1 = 0 (marked in green). Additional features of the spectra that deserve mention are significant t1-ridges (marked in blue), which arise from a combination of t1-noise, sinc character due to t1-truncation and phase-twist lineshape (marked in pink), which extends signals considerably in both F1 and F2 dimensions and introduces further distortions where signals overlap.

Figure 2.

J-PRESS spectra of a phantom containing commonly observed neurochemicals and lactate at (a) 3T and (b) 7T. Both spectra are plotted in magnitude mode. Note the increased presence of signals at F1 = 0 (e.g. for the lactate doublet at 1.3 ppm) in the 7T spectrum compared to 3T (additional ‘J-refocused’ peaks marked in green). The ‘phase-twist’ lineshape is readily apparent for the singlet Cho, Cr and NAA resonances, particularly in the 3T spectrum (marked in pink). ‘t1-ridges’, arising from a combination of t1-noise and sinc character due to t1-truncation, are marked in blue. Experimental details are given in the text.

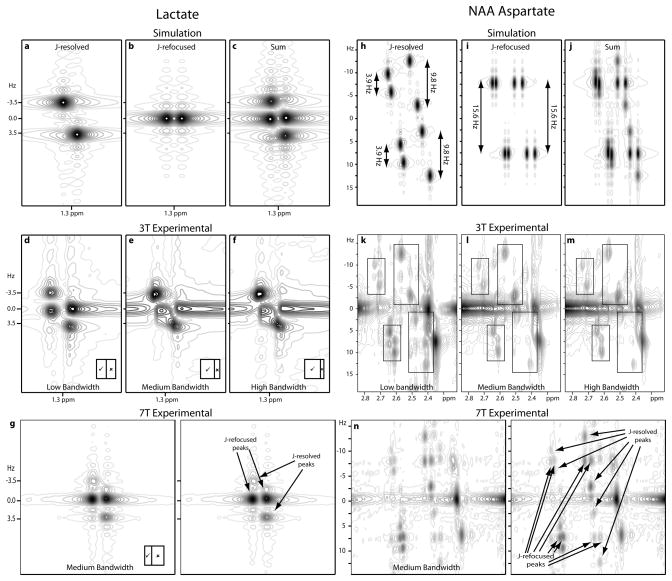

Simulation of J-resolved peaks in Figure 3a clearly shows the expected position of the peaks. Figure 3b shows the peaks that arise if the J-coupling does not evolve during t1. The sum of these two (in Figure 3c) is qualitatively similar to Figure 3d, which is an expansion of the lactate region of the spectrum in Figure 2a. Peaks are slightly perturbed from perfect alignment in both spectra due to the ‘phase-twist’ character of the peaks. Figure 3e and 3f show the same region of spectra acquired with medium- and high-bandwidth refocusing pulses.

Figure 3.

Expanded regions of J-PRESS spectra for lactate (a–g) and NAA aspartyl CH2 (h–n) multiplets. (a) Simulated J-resolved doublet (corresponding to the time-domain signal in Equation 1). (b) Simulated J-refocused doublet (corresponding to the time-domain signal in Equation 2). (c) Sum of (a) and (b). Experimental data acquired with (d) low-, (e) medium-, and (f) high-bandwidth refocusing pulses at 3T. (g) Experimental data acquired at 7T, which is shown twice to accommodate arrows denoting the J-resolved and J-refocused peaks. Inserts in (d–g) show the relative sizes of the two compartments: ✓ denotes the region in which the passive spin does undergo the refocusing pulse and ✘ denotes that in which the passive spin does not undergo the refocusing pulse. (h) Simulated J-resolved spectrum (corresponding to the time-domain signal in Equation 3). (i) Simulated spectrum (corresponding to the time-domain signal in Equation 4) in which the two vicinal couplings are refocused during t1. (j) Sum of (h) and (i). Experimental data acquired with (k) low-, (l) medium-, and (m) high-bandwidth refocusing pulses at 3T. Boxes highlight the NAA CH2 signals. (n) Experimental data acquired at 7T using the GTST medium-bandwidth refocusing pulse, shown twice to accommodate arrows denoting the J-resolved and J-refocused peaks without obscuring data.

In Figure 2, additional peaks are also apparent within the NAA aspartate signals at ~2.6 ppm (also marked in green); this region is expanded in Figure 3k. The aspartate moiety in NAA is an ABX spin system with spins at 4.38 ppm, 2.67 ppm and 2.49 ppm, with geminal coupling of 15.6 Hz and vicinal coupling constants of 3.9 Hz and 9.8 Hz (15). The additional peaks observed are consistent with refocusing of the vicinal couplings during t1.

Comparing Figures 3e and 3f to 3d, it can be seen that increasing the bandwidth of slice-selective refocusing pulses reduces the intensity of the ‘J-refocused’ peaks in the spectrum (although the effect is made less striking by significant smeared signal at F1 = 0 from strong singlet resonances). Similarly, comparing Figures 3l and 3m to 3k shows a significant reduction in the intensity of ‘J-refocused peaks’ in NAA.

Expansions of the equivalent region of a 7T J-PRESS spectrum in Figure 3g and 3n show very similar effects, although the intensity of the ‘J-refocused’ peaks is greater.

Discussion

Why do these additional peaks appear? It has been shown elsewhere that finite-bandwidth slice-selective refocusing pulses impact the evolution of couplings during the echo time of PRESS-based experiments (4–10). Because the spatial extent of slice-selective refocusing is different for different chemical shifts, coupled spins with significantly different chemical shift will not both undergo refocusing pulses in all regions of the PRESS-excited volume. Spin echoes in which only one coupled spin experiences the 180° pulse refocus the evolution of coupling, and so during the echo time coupling evolves in some regions of the PRESS volume and is refocused in others. This leads to significant loss of lactate signal in long TE-PRESS (7) and GABA signal in MEGA-PRESS (16).

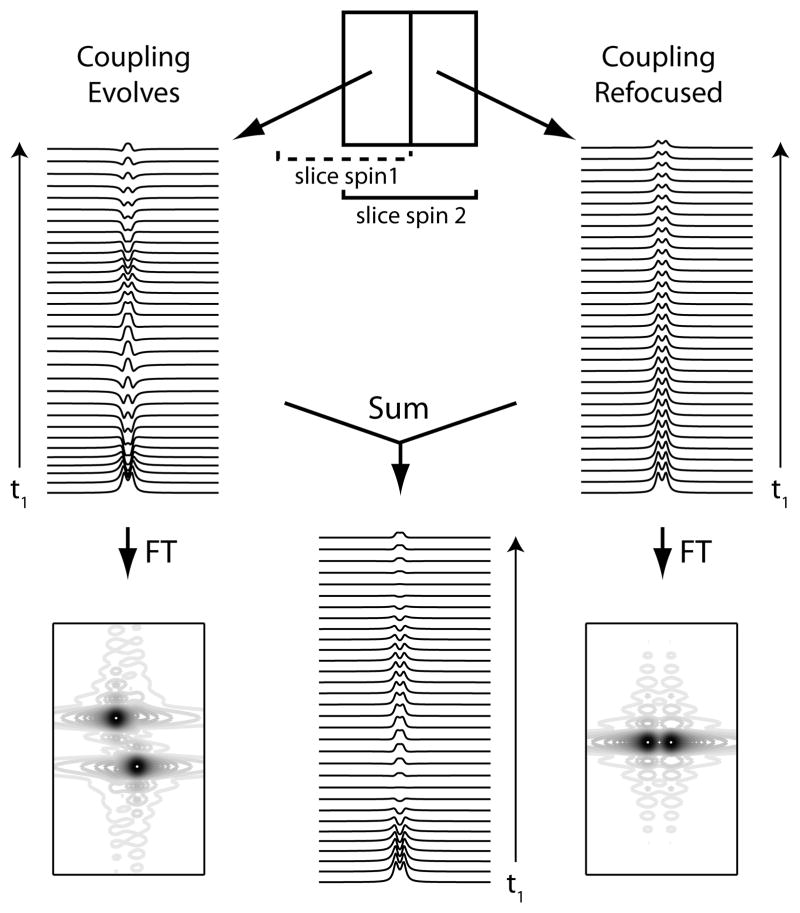

In the J-PRESS experiment, couplings between spins that do or do not both undergo the refocusing pulse will either evolve or be refocused during TE, resulting in different modulation of signals as a function of t1, as seen in Figure 4. The signal acquired from the full PRESS volume will therefore be the weighted sum of the ‘coupling evolves’ (with weight (1−δ)) and ‘coupling refocused’ (with weight δ) signals from within the PRESS volume. In contrast to long-echo time PRESS, this does not result in a simple loss of signal, but separation of signal intensity into two separate doublets, the J-resolved doublet and J-refocused doublet, according to t1 behavior.

Figure 4.

Time (t1) series of simulated lactate data. Where both coupled spins undergo the refocusing pulse (schematic top centre), coupling evolves during t1 resulting in a doublet that modulates from fully positive to fully negative (above left). Fourier transformation of this data yields the spectrum previously shown in Figure 3a. Where the passive spin does not undergo the refocusing pulse, coupling does not evolve during t1 resulting in a doublet that is not modulated (above right). Fourier transformation of this data yields the spectrum previously shown in Figure 3b. The (unweighted) time-domain sum of these two is modulated from a positive doublet to no signal (center).

In the case of lactate, this means that each doublet gives rise to four signals in the J spectrum – the two expected J-resolved peaks, and two additional ‘refocused’ peaks on the F1=0 axis. As can be seen in Figure 3, the relative intensity of the J-refocused peaks is reduced when the bandwidth of the refocusing pulses is increased, because the J-refocused fraction δ of the PRESS volume is reduced as BW increases.

The behavior of the aspartate spins of NAA is more complicated, because there is only a large chemical shift displacement associated with the vicinal couplings and almost none associated with the geminal coupling (since both CH2 signals have very similar chemical shift). Thus, in one part of the PRESS-excited volume, all couplings evolve and in the other the geminal coupling evolves and the vicinal couplings are refocused. In the J-refocused spectrum seen in Figure 3h, the signals do not appear at F1 = 0 because the geminal coupling evolution during t1 still results in splitting in F1.

Similar artifacts

The ‘J-refocused’ peaks described here are similar to the ‘ghost’ peaks observed by Bodenhausen et al. in heteronuclear J-spectra with imperfect refocusing (17). However there is a difference in that ‘ghosts’ result from coupled terms in which the active spin does not undergo the refocusing pulse and can thus be removed by phase cycling or pulsed field gradients. The peaks we observe follow the same coherence transfer pathway as the J-resolved peaks (differing only in the treatment of the passive spin) and so cannot be removed by phase cycling or gradients. Ghost peaks have been observed in J-PRESS by Ryner et al. (1) (see e.g. Figure 5c, a tilted J-spectrum of alanine showing the F1=0 J-refocused doublet), but to our knowledge, there has been no previous description of J-refocused peaks arising from the chemical shift displacement effect. Additional artifactual peaks appear in J-spectra due to strong coupling and symmetrization (1,17,18).

Implications of the artifact

The implications of this effect for the J-PRESS method are two-fold - the appearance of twice as many peaks in the spectrum for a multiplet will reduce the extent to which signals can be resolved, and the division of signal intensity will result in lower peak SNR for multiplets in the 2D spectrum by a fraction (1−δ). If J-PRESS spectra are analyzed using fitting methods which use ‘basis functions’ (2,3), it is important that the basis functions are generated either by experimentally acquiring them under the same conditions as used for in vivo spectroscopy, or simulated with refocusing pulses of the appropriate experimental bandwidth. Further reductions in resolution in J-PRESS are particularly unwanted since the method already suffers from the 2D ‘phase-twist’ lineshape arising from acquisition of a single coherence transfer pathway during t1, the indirectly acquired dimension; this results in dispersive tails that can be seen prominently in Figure 2.

Comparison of 7T data with 3T data (i.e. Figure 3e vs. 3g and 3l vs. 3n) demonstrates that bandwidth effects become more severe at higher field. This arises because the chemical shift difference ΔΩ between coupled spins is greater by a factor of 7/3, whereas no corresponding increase in B1 field strength is usually possible due to hardware and SAR constraints, so that BW is approximately constant.

Several strategies have been used to mitigate spatially-variant coupling effects in the PRESS experiment. In addition to the use of high bandwidth refocusing pulses as applied here, the inner-volume saturation (IVS) method may also be used (19) both in PRESS-IVS and MEGA-PRESS-IVS (16), and involves the suppression of signal in those regions of the PRESS volume in which coupling evolution is not optimal. Some solutions (6,10) designed to address lactate signal loss result in the complete refocusing of coupling evolution, however these methods are clearly not applicable to J-PRESS. Finally, the PRESS+4 method (5) uses an additional hard 180° pulse during the MEGA-PRESS sequence to ensure coupling evolution throughout the PRESS-volume.

The key point of this study is that only couplings that modulate signals in t1 will give J-resolved peaks in the J-spectrum, or to put it another way, signal from those regions of the PRESS box in which a J-coupling is refocused will not be resolved by that coupling in F1 in the spectrum. This means that a doublet may give rise to four signals in the J-spectrum – the two expected J-resolved peaks, and two additional ‘refocused’ peaks on the F1 = 0 axis. Peaks are also duplicated in the case of more complicated spin systems, although these peaks do not necessarily lie on F1 = 0. These effects impact the SNR and resolution of J-PRESS and have been shown to be reduced in intensity by the application of high-bandwidth refocusing pulses.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grants P41 RR15241 and R21 MH082322.

Footnotes

Matlab code for generating and displaying simulated datasets is available on request.

References

- 1.Ryner LN, Sorenson JA, Thomas MA. Localized 2D J-resolved 1H MR spectroscopy: strong coupling effects in vitro and in vivo. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13(6):853–869. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)00031-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen JE, Licata SC, Ongur D, Friedman SD, Prescot AP, Henry ME, Renshaw PF. Quantification of J-resolved proton spectra in two-dimensions with LCModel using GAMMA-simulated basis sets at 4 Tesla. NMR Biomed. 2009;22(7):762–769. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulte RF, Boesiger P. ProFit: two-dimensional prior-knowledge fitting of J-resolved spectra. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(2):255–263. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung WI, Bunse M, Lutz O. Quantitative evaluation of the lactate signal loss and its spatial dependence in press localized (1)H NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 2001;152(2):203–213. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaiser LG, Young K, Matson GB. Elimination of spatial interference in PRESS-localized editing spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(4):813–818. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley DA, Wald LL, Star-Lack JM. Lactate detection at 3T: compensating J coupling effects with BASING. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9(5):732–737. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199905)9:5<732::aid-jmri17>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange T, Dydak U, Roberts TP, Rowley HA, Bjeljac M, Boesiger P. Pitfalls in lactate measurements at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(4):895–901. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall I, Wild J. A systematic study of the lactate lineshape in PRESS-localized proton spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40(1):72–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson RB, Allen PS. Sources of variability in the response of coupled spins to the PRESS sequence and their potential impact on metabolite quantification. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(6):1162–1169. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199906)41:6<1162::aid-mrm12>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yablonskiy DA, Neil JJ, Raichle ME, Ackerman JJ. Homonuclear J coupling effects in volume localized NMR spectroscopy: pitfalls and solutions. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(2):169–178. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murdoch JB. Proceedings of the 10th ISMRM Scientific Meeting; Hawai’i. 2002. p. 923. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edden RA, Pomper MG, Barker PB. In vivo differentiation of N-acetyl aspartyl glutamate from N-acetyl aspartate at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(6):977–982. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henning A, Fuchs A, Murdoch JB, Boesiger P. Slice-selective FID acquisition, localized by outer volume suppression (FIDLOVS) for (1)H-MRSI of the human brain at 7 T with minimal signal loss. NMR Biomed. 2009;22(7):683–696. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tkac I, Starcuk Z, Choi IY, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain at 1 ms echo time. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(4):649–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<649::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govindaraju V, Young K, Maudsley AA. Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2000;13(3):129–153. doi: 10.1002/1099-1492(200005)13:3<129::aid-nbm619>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edden RA, Barker PB. Spatial effects in the detection of gamma-aminobutyric acid: improved sensitivity at high fields using inner volume saturation. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1276–1282. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodenhausen G, Freeman R, Turner DL. Suppression of artifacts in two-dimensional J spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1977;27(3):511–514. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thrippleton MJ, Edden RA, Keeler J. Suppression of strong coupling artefacts in J-spectra. J Magn Reson. 2005;174(1):97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edden RA, Schar M, Hillis AE, Barker PB. Optimized detection of lactate at high fields using inner volume saturation. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(4):912–917. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]