Abstract

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) is a potent constrictor of isolated blood vessels. However, recent studies demonstrate that chronic 5-HT infusion results in a prolonged fall in blood pressure in the rat. This finding highlights the need for further study of 5-HT in the cardiovascular system. We tested the hypothesis that a functional serotonin transporter (SERT) is critical to enabling a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure. Experiments were performed in male and female rats to determine whether gender significantly affected the ability of 5-HT to lower blood pressure and to determine whether SERT dependence was different in male vs. female rats. 5-HT (25 μg/kg/min; s.c.) was infused for 7 days to male and female, SERT wild-type (WT) and SERT knockout (KO) rats. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were monitored via radiotelemetry. 5-HT produced a significantly greater fall in MAP (at the nadir) in the male SERT WT rat (−20±1 mmHg) compared to the male SERT KO rat (−10±2 mmHg). Similarly, 5-HT also produced a significantly greater fall in MAP (at the nadir) in the female SERT WT rat (−19±1 mmHg) compared to the female SERT KO rat (−15±0.4 mmHg). While the lack of a functional SERT protein did not prevent a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure, it did reduce the ability of 5-HT to lower blood pressure in the male and female SERT rat, suggesting a potentially important role for SERT in producing a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure.

Keywords: Serotonin, 5-Hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT, Serotonin transporter (SERT), Blood pressure

Introduction

5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a vasoactive amine synthesized in the enterochromaffin cells of the gastrointestinal tract and the raphe nucleus in the central nervous system (Erspamer and Aerso 1952; Dahlstroem and Fuxe 1964). It is a potent constrictor of isolated blood vessels (Rapport et al. 1948), and its actions are terminated by the enzymatic activity of monoamine oxidase.

Elevated levels of free plasma 5-HT are present in both human and experimental models of hypertension (Brenner et al. 2007; Fetkovska et al. 1990). Initially, this led investigators to postulate that 5-HT might be acting to constrict the peripheral vasculature, resulting in elevated blood pressure. However, chronic 5-HT infusion produced a prolonged fall in blood pressure in the DOCA–salt and sham rat (Diaz et al. 2008). This suggested elevated free plasma 5-HT might be acting to lower blood pressure in both human and animal models of hypertension. Thus, 5-HT might represent an adaptation to elevated pressure, rather than a contributing factor to essential hypertension. Interestingly, Diaz et al. demonstrated that inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) prevented a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure, suggesting an important role for NOS and likely nitric oxide (NO) in eliciting a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure. However, the exact mechanism underlying a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure is not yet fully understood.

Several studies implicate the importance of the serotonin transporter (SERT) as mechanistically important in mediating the effects of 5-HT. Chanrion et al. demonstrated 5-HT uptake via SERT enhanced neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) activity in cells coexpressing both SERT and nNOS (Chanrion et al. 2007). This led Chanrion et al. to speculate that 5-HT uptake via SERT leads to an allosteric change in nNOS, which increases its affinity for calmodulin, resulting in activation. This suggests elevated levels of free 5-HT may be taken up via SERT leading to nNOS activation, NO production, and lower blood pressure.

Moreover, reports also suggest that 5-HT can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) via SERT (Nakatani et al. 2008). Thus, elevated levels of peripheral 5-HT might potentially cross the BBB and act centrally to activate nNOS via SERT uptake. Collectively, this evidence suggests that SERT may play an important role in eliciting a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure. We tested the hypothesis that SERT function and 5-HT uptake is essential to enabling a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure.

To test this hypothesis, we utilized the SERT knockout (SERT KO) rat created by Edwin Cuppen [ethylnitrosurea-induced mutagenesis on a Wistar rat background] (Homberg et al. 2007). Previous studies validated the absence of a functional SERT and the presence of a truncated protein in the male SERT KO rat through immunohistochemical staining and western blot analysis (Linder et al. 2008a, b). Finally, reports suggest SERT may function differently in males vs. females (Maron et al. 2011). Thus, we investigated chronic 5-HT infusion in male and female rats to determine whether gender significantly affected the ability of 5-HT to lower blood pressure.

Methods

Animal use

Male and female SERT KO and Wistar-based wild-type (WT) rats (Charles River) were used in these studies. The SERT KO and WT rats were bred at Michigan State University under a breeding license obtained from genO-way®. All animal use procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University.

Experimental protocol

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and implanted with radiotelemetry devices (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN USA: PA-C40 introduced via the femoral artery). Rats were allowed 4 days to recover, and 3 days of baseline measurements were made. An Alzet® osmotic pump (Model 2ML1, Duret Corporation, Cupertino, CA; 10μl/h 7 days) containing 5-HT (25 μg/kg/min) was inserted subcutaneously at the base of the neck. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were monitored for the duration of the study. In Table 1, we report MAP and HR on the 2nd control day as well as at the nadir. Hemodynamic measurements were sampled for 10 s every 10 min for the duration of the experiment. Data are reported as 24-h averages. Blood was collected at the end of the study and fractionated into platelet poor plasma to validate elevated free plasma 5-HT levels using high-performance liquid chromatography.

Table 1.

MAP and HR changes in male and female SERT WT and SERT KO rats

| Model | Control |

Nadir |

Δ

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Heart Rate (bpm) | Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Heart Rate (bpm) | Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Heart Rate (bpm) | |

| Male SERT WT (n=8) | 106±1 | 348±6 | 85±1 | 422±6 | 21±1.0* | 74±5 |

| Male SERT KO (n=7) | 101±2 | 355±7 | 90±2 | 412±7 | 11±2.0 | 57±8 |

| Female SERT WT (n=8) | 113±1 | 366±3 | 93±2 | 440±4 | 19±1.0* | 75±5 |

| Female SERT KO (n=7) | 106±2 | 387±4 | 91±2 | 456±2 | 15±0.4 | 69±5 |

Data are mean±SEM

p<0.05, compared with SERT KO

Plasma 5-HT collection

Blood collection and platelet-poor-plasma (PPP) preparation were conducted according to our previously published methods (Diaz et al. 2008). Briefly, 5 ml of blood was collected from left cardiac ventricle using a heparin-coated syringe. The blood was transferred into an EDTA anticoagulant vacutainer tube. The tubes were spun at 160×g for 30 min for platelet-rich-plasma. The supernatant containing plasma and buffy coat were pipetted into EDTA-coated plastic tubes. These tubes were centrifuged at 1,350×g for 20 min for PPP. To the remaining pellet (platelet layer), 1 ml of platelet buffer and 1 μmol/l ADP was added. Ten micromoles per liter of pargyline and 10 μmol/l ascorbic acid were added. The tubes were centrifuged at 730×g for 10 min. Ten percent of trichloroacetic acid was added to deproteinize both sets of samples. All tubes were centrifuged at 4,500×g for 20 min. Finally, samples were ultracentrifuged at 280,000×g for 2 h. 5-HT concentrations were measured using HPLC at 0.4 V and 0.9 ml/min flow rate.

Data analysis

For in vivo data analysis, within-group differences were assessed by a one-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons using Student–Newman–Keuls test (GraphPad Prism 5). An unpaired Students t test was performed to measure point-to-point differences. In all cases, a p value of <0.05 was considered significant. All results are presented as means±SEM.

Results

In the male rat, chronic 5-HT infusion significantly (p< 0.05) elevated free plasma 5-HT levels in the SERT WT rat (61±16.2 ng/ml) compared to baseline measures (8.6±1.3 ng/ml). Similarly, chronic 5-HT infusion also elevated free plasma 5-HT levels in the SERT KO rat (37.3±24.2 ng/ml) compared to baseline measures (1.1±0.5 ng/ml). At baseline, free plasma 5-HT levels were significantly higher in the SERT WT (8.6±1.3 ng/ml) compared to the SERT KO rat (1.1±0.5 ng/ml) rat (p<0.05).

In the female rat, chronic 5-HT infusion also significantly (p<0.05) elevated free plasma 5-HT levels in the SERT WT (62±8.4 ng/ml) compared to baseline measures (3.9±0.6 ng/ml). Similarly, chronic 5-HT infusion also elevated free plasma 5-HT levels in the SERT KO rat (23±7.3 ng/ml) compared to baseline (1.9±1.0 ng/ml). At baseline, free plasma 5-HT levels were not significantly different in the SERT WT (3.9±0.6 ng/ml) compared to the SERT KO (1.9±1.0 ng/ml) rat.

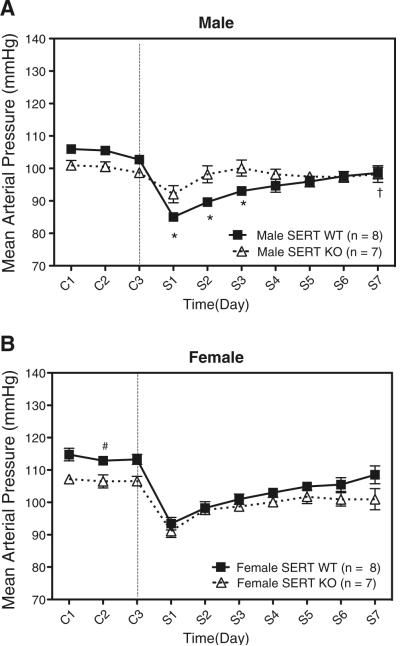

Table 1 summarizes changes in MAP and HR. MAP fell rapidly in all models reaching a nadir after 24–48 h (Fig. 1). HR was elevated (at the nadir) in all models following 5-HT infusion, but not statistically different between groups. Both MAP and HR trended toward baseline (C2) throughout the remainder of the study.

Fig. 1.

a Effect of chronic 5-HT infusion on mean arterial pressure (MAP) in male SERT WT and SERT KO rats. b Effect of chronic 5-HT infusion on mean arterial pressure (MAP) in female SERT WT and SERT KO rats. Data points indicate 24-h averaged MAP±SEM for the number of animals in parentheses. The vertical line denotes 5-HT or vehicle osmotic pump implant. Time is represented by days on the x-axis. C represents control recordings. S represents 5-HT infusion. Single asterisk reperesents statistically significant (p<0.05) difference compared with male SERT KO rat. Single dagger sign represents statistically significant (p<0.05) difference compared to control (C2) in male SERT WT rat. Single number sign represents statistically significant (p<0.05) difference compared to control (C2) in female SERT KO rat (C2)

In the male rat, 5-HT produced a significantly greater fall in MAP in the SERT WT rat (−20±1 mmHg) compared to the SERT KO rat (−10±2 mmHg; Fig. 1a). MAP remained significantly lower in the SERT WT rat compared to the SERT KO rat during the 2nd and 3rd day of 5-HT infusion. MAP in the SERT WT also never returned to baseline (C2) at the end of the 7-day infusion, whereas it returned to baseline in the SERT KO.

In the female rat, 5-HT produced a significantly greater fall in MAP in the SERT WT (−19±1 mmHg) compared to the SERT KO (−15±0.4 mmHg) rat (Fig. 1b). Baseline (C2) MAP was greater in the SERT WT rat (112±1.3 mmHg) compared to the SERT KO rat (106±2.0 mmHg). MAP in both the SERT WT and SERT KO returned to baseline (C2) by the end of the study. There was no significant difference in the fall in MAP between the male and female SERT WT or the male and female SERT KO rats.

Discussion

This study investigated whether a functional SERT protein was essential to enabling a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure. The absence of a functional SERT protein significantly reduced the magnitude of the 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure in the SERT KO rat. This suggests an important role for 5-HT uptake in mediating a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure in the Wistar rat.

The mechanisms by which SERT participates in a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure are numerous. However, the most compelling evidence for SERT involvement in a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure is provided by Chanrion et al. who suggest that 5-HT uptake via SERT may activate nNOS and stimulate NO release. Interestingly, both arteries and veins also possess SERT and actively take up 5-HT (Ni et al. 2004; Linder et al. 2008a, b). This suggests elevated free 5-HT may be taken up into the vasculature via SERT and lead to activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and release of NO.

The present study also sought to determine whether gender affected the ability of 5-HT to lower blood pressure. No statistical differences in MAP were noted between the male SERT WT vs. the female SERT WT or the male SERT KO vs. the female SERT KO at the nadir. The absence of a functional SERT significantly reduced the ability of 5-HT to lower blood pressure in both male and female Wistar rats. Therefore, we conclude gender does not significantly impact a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure.

While the absence of a functional SERT significantly reduced the ability of 5-HT to lower blood pressure, it did not completely abolish a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure. Therefore, this raises questions about whether 5-HT might be taken up by another transporter. Alternatively, another mechanism might exist, besides 5-HT uptake, which contributes to a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure.

Further, one might expect free 5-HT levels to be higher in 5-HT-infused SERT KO rats compared to 5-HT-infused SERT WT rats due to the absence of a functional SERT to take up exogenously delivered 5-HT. However, following 5-HT infusion, we observed higher levels of free 5-HT in the SERT WT compared to the SERT KO rat. This raises questions about where exogenously delivered 5-HT might be deposited or whether 5-HT may be rapidly excreted in the SERT KO rat compared to the SERT WT rat.

Finally, we acknowledge that chronic 5-HT infusion will likely result in downregulation of SERT. Thus, we speculate that if 5-HT uptake via SERT is critical to enabling a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure, then downregulation of SERT may correlate with the observed trend in MAP (Fig. 1) back towards baseline in 5-HT-infused SERT WT and SERT KO rats. In summary, this study suggests an important role for 5-HT uptake in enabling a 5-HT-induced fall in blood pressure in the Wistar rat.

References

- Brenner B, Harney JT, Ahmed BA, Jeffus BC, Unal R, Mehta JL, Kilic F. Plasma serotonin levels and the platelet serotonin transporter. J Neurochem. 2007;102:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanrion B, Mannoury la Cour C, Bertaso F, Lerner-Natoli M, Freissmuth M, Millan MJ, Brockaert J, Martin P. Physical interaction between the serotonin transporter and neuronal nitric oxide synthase underlies reciprocal modulation of their activity. PNAS. 2007;104:8119–8124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610964104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstroem A, Fuxe K. Evidence for the existence of monamine-containing neurons in the central nervous system. I. Demonstration of monamines in the cell bodies of brain stem neurons. Acta Physiol Scand. 1964;232(Suppl):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz J, Ni W, Thompson J, King A, Fink G, Watts SW. 5-hydroxytryptamine lowers blood pressure in normotensive and hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:1031–1038. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erspamer V, Aerso B. Identification of enteramine, the specific hormone of the enterochromaffin cell system, as 5-hydroxytryptamine. Nature. 1952;169:800–801. doi: 10.1038/169800b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetkovska N, Pletscher A, Ferracin F, Amstein R, Buhler FR. Impaired uptake of 5-hydroxytryptamine in platelet in essential hypertension: clinical relevance. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1990;4:105–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00053439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg JR, Olivier JDA, Smits BMG, Mul JD, Mudde J, Verheul NOFM, Cools AR, Ronken E, Cremers T, Schoffelmeer ANM, Ellenbroek BA, Cuppen E. Characterization of the serotonin transporter knockout rat: a selective change in the functioning of the serotonergic system. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1662–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder AE, Diaz J, Ni W, Szasz T, Burnett R, Watts SW. Vascular reactivity, 5-HT uptake, and blood pressure in the serotonin transporter knockout rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008a;294:H1745–H1752. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91415.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder AE, Ni W, Szasz T, Burnett R, Diaz J, Geddes TJ, Kuhn DM, Watts SW. A serotonergic system in veins: serotonin transporter-independent uptake. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008b;325:714–722. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron E, Toru I, Hirvonen J, et al. Gender differences in brain serotonin transporter availability in panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0269881110389207. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani Y, Sato-Suzuki I, Tsujino N, Nakasato A, Seki Y, Fumoto M. Augmented brain 5-HT crosses the blood-brain barrier through the 5-HT transporter in rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2466–2472. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Thompson JM, Northcott CA, Lookingland K, Watts SW. The serotonin transporter is present and functional in peripheral arterial smooth muscle. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;43:770–781. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MM, Green AA, Page IH. Serum vasoconstrictor (serotonin): IV isolation and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1948;176:1243–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]