Abstract

Efficient syntheses of suitably functionalized top and bottom fragments of tetrafibricin are described. The bottom fragment is prepared by two consecutive Kocienski-Julia couplings, while the top fragment synthesis features a dithiane alkylation and a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction.

Keywords: tetrafibricin, natrual product synthesis, fibrinogen, dithiane

1. Introduction

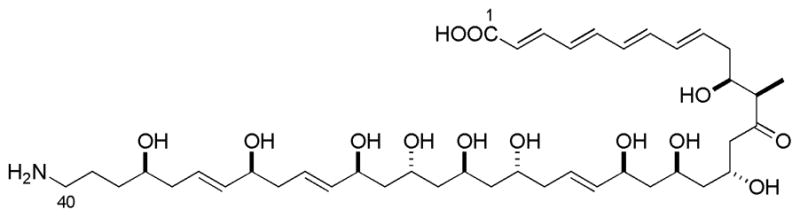

During the course of a screening program for fibrinogen receptor antagonists, Kamiyama and coworkers isolated tetrafibricin 1 from the culture broth of streptomyces neya–gawaensis NR0577, and assigned its two-dimensional structure.1 In 2003, Kishi elucidated the complete stereochemistry of tetrafibricin (Figure 1) by using NMR databases along with experiments in achiral and chiral solvents.2 Tetrafibricin inhibits the binding of fibrinogen to its receptors with an IC50 of 46 nM and inhibits aggregation of human platelets induced by ADP, collagen, and thrombin. Accordingly, it has potential therapeutic applications for thrombotic diseases such as coronary occlusion and myocardial infarction.3

Figure 1.

Structure of tetrafibricin 1

In synthetic progress to date, Cossy prepared C1–C13, C15–C26, and C27–C40 fragments,4 while Roush made a C1–C19 fragment.5 We have described routes to several fragments and have joined a single C21–C30 fragment with quasiisomers of other fragments in a fluorous mixture synthesis (FMS) of four stereoisomers of the C21–C40 fragment of tetrafibricin.6 This work featured Kocienski-Julia reactions, which have also recently been exploited by Friestad to make a C24-C40 fragment.7

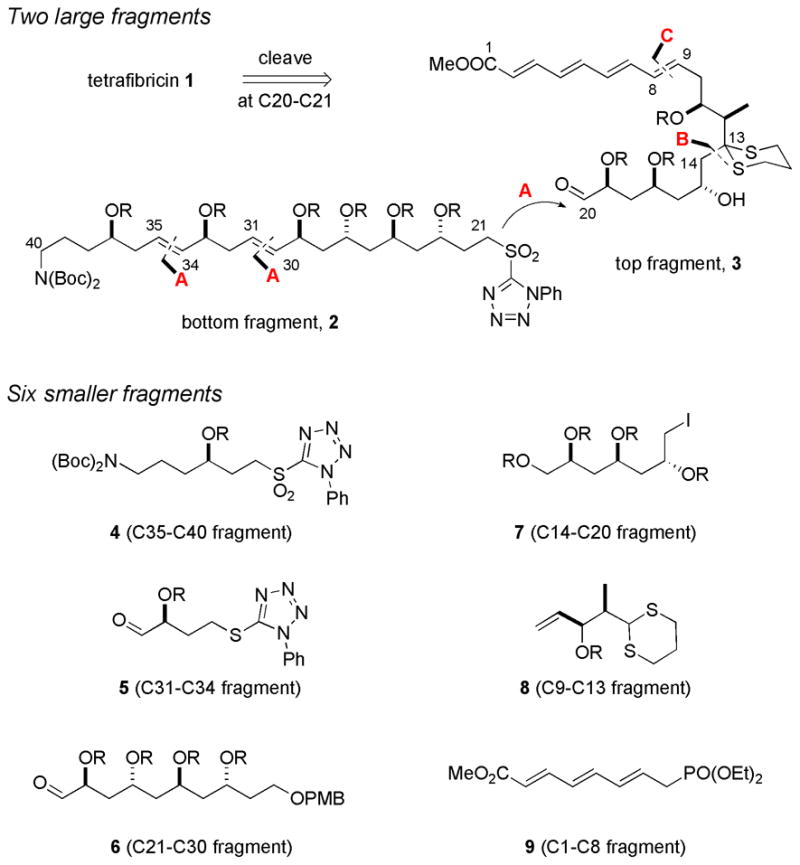

Here we describe convergent routes to single stereoisomers of the C1–C20 and C21–C40 fragments of tetrafibricin. The recently published FMS fragment synthesis6 was patterned after the route described herein. The retrosynthetic analysis of tetrafibricin is outlined in Figure 2. Cleavage at the strategic C20–C21 alkene provides large bottom 2 and top 3 fragments.

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis with six main fragments 4–9. A = Kocienski-Julia rxn; B = Dithiane alkylation; C = HWE rxn; R = TBS (tert-butyldimethysilyl).

A series of Kocienski-Julia reactions (A)8 with appropriate aldehydes and sulfones allows the formation of C20–C21, C30–C31 and C34–C35 bonds from fragments 4 (C35–C40), 5 (C31–C34), and 6 (C21–C30). Disconnection at C13–C14 bond of 3 provides iodide 7 (C14–C20) and dithiane 8 (C9–C13), which will be coupled by alkylation (B).9 Disconnection at C8–C9 provides fragment 9 (C1–C8) as a partner for Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons (HWE) olefination (C).

2. Results and Discussion

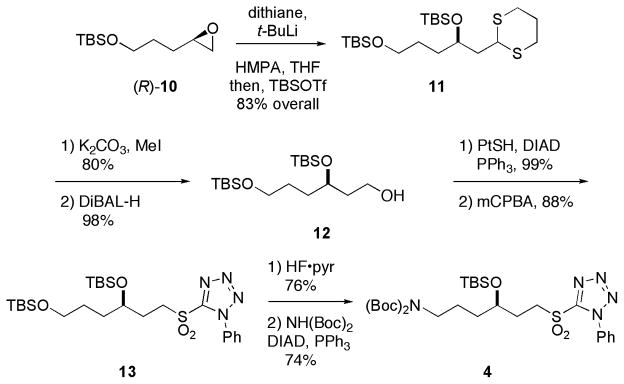

C35–C40 Fragment

The synthesis of C35–C40 sulfone 4 is shown in Scheme 1. Epoxide (R)-10 is readily available in 96% ee by Jacobsen hydrolytic kinetic resolution of the corresponding racemate (prepared by silylation and epoxidation of pent-4-en-1-ol).6b,10 Reaction of (R)-10 with lithio-1,3-dithane followed by trapping with TBS-triflate afforded 11 in 83% yield. Hydrolysis of dithiane 11 gave an aldehyde (80% yield)11 that was reduced with DiBAL-H to give alcohol 12 in 98% yield. This was converted to an alkylthiophenyltetrazole by a Mitsunobu reaction, and then the sulfide was oxidized to provide sulfone 13. Selective cleavage of the primary silyl ether, followed by reaction of the primary alcohol with di-tert-butyl-iminodicarboxylate in presence of DIAD, provided 4 in 74% yield.12

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of sulfone 4 (C35–C40). PtSH = 1-phenyl,5-thiotetrazole, DIAD = diisopropylazodicarboxylate.

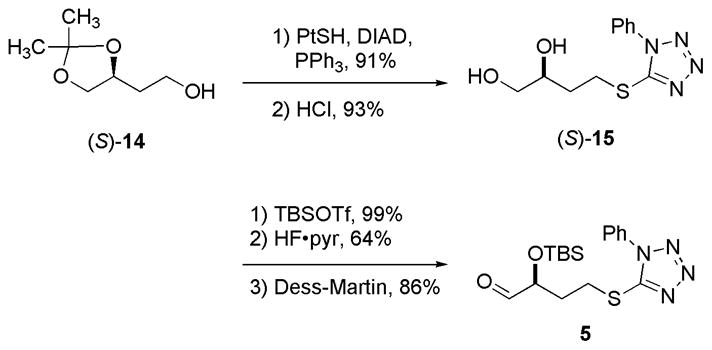

C31–C34 Fragment

The synthesis of C31–C34 aldehyde 5 commenced with the commercially available (S)-2-(2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)ethanol (S)-14 as shown in Scheme 2. Alcohol (S)-14 was subjected to a Mitsunobu reaction to incorporate phenylthiotetrazole, then the acetal was cleaved to give diol 15. Bis-silylation of the diol 15, followed by selective cleavage of the primary silyl-ether and oxidation of the corresponding primary alcohol with the Dess-Martin reagent furnished aldehyde 5 in 54% yield over the three steps.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of aldehyde 5 (C31–C34).

C21–C30 Fragment

Aldehyde 6 was prepared from (S)-2,2-dimethyl-4-((S)-oxiran-2-ylmethyl)-1,3-dioxolane as previously described.6 The published route to 6 takes nine steps and gives 18% yield overall.

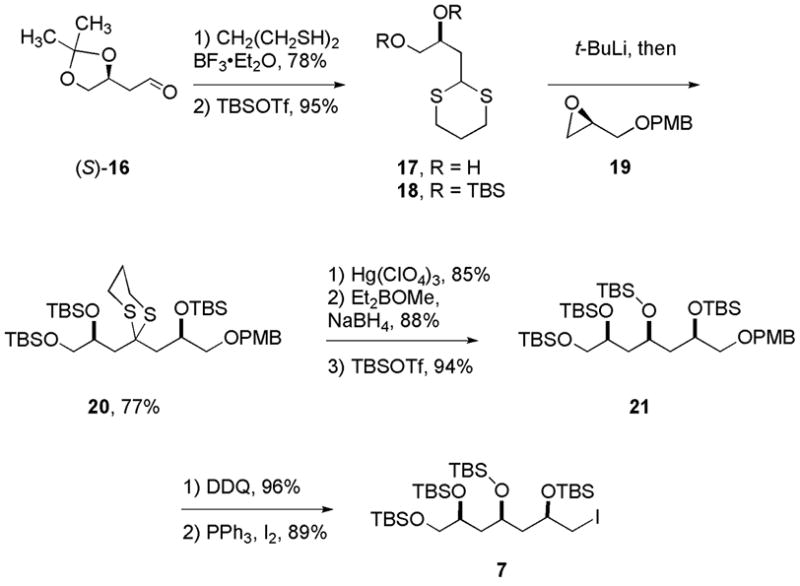

C14–C20 Fragment

The synthesis of the C14–C20 fragment is shown in Scheme 3. The reaction of aldehyde 16 with propane-1,3-dithiol in presence of BF3·OEt213 resulted in conversion of aldehyde to the 1,3-dithiane and simultaneous removal of the acetal. Diol 17 was isolated in 78% yield. Silylation of the diol (TBSOTf and 2,6-lutidine) proceeded smoothly to give bis-silyl ether 18 in 95% yield. Deprotonation of 18 with t-BuLi and reaction of the derived dithiane anion with epoxide 19 provided 20 in 77% yield. Dithiane hydrolysis (85%) followed by directed reduction provided a 1,3-diol bis-silyl ether that was further protected with TBSOTf to provide tetrakis-silyl ether 21 in 70% yield over three steps. Cleavage of the PMB-ether with DDQ followed by conversion of the corresponding primary alcohol to iodide14 completed the synthesis of C14–C20 fragment 7.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of aldehyde 7 (C14–C20).

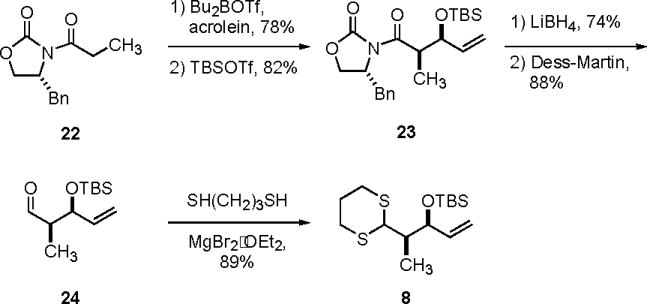

C9–C13 Fragment

The synthesis of dithiane 8 is illustrated in Scheme 4. Asymmetric aldol reaction of the freshly distilled acrolein with oxazolidinone 2215 (78%) followed by protection of the derived secondary alcohol provided adduct 23 in 82% yield. Reduction of oxazolidinone 23 with LiBH4 followed by oxidation of the resulting primary alcohol with Dess-Martin reagent afforded aldehyde 24 in 88% yield. Addition of propane-1,3-dithiol and MgBr2·OEt2 to aldehyde 24 in THF furnished dithiane 8 in 89% yield.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of dithiane 8 (C9–C13).

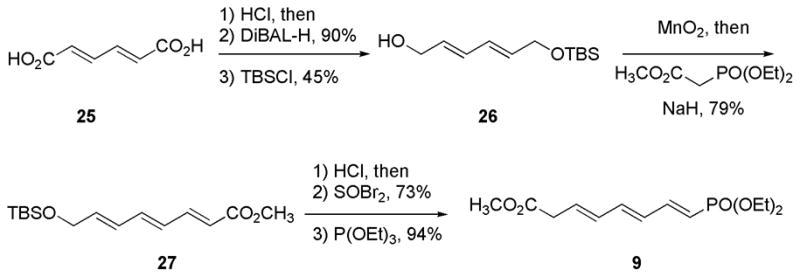

C1–C8 Fragment

The synthesis of phosphonate 9 is shown in Scheme 5. Alcohol 26 was readily prepared from (E,E)-muconic acid 25 in a three step sequence consisting of esterification, reduction and finally TBS-protection (40% yield overall). Oxidation of the alcohol16 followed by HWE-olefination of the corresponding aldehyde with methyl-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)-acetate provided triene 27 in 79% yield. Cleavage of the TBS ether, conversion of the resulting allylic alcohol to bromide, then treatment of the bromide with excess triethylphosphite17 in toluene to give the target phosphonate (E,E,E)-9 in 94% yield.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of phosphonate 9 (C1–C8)

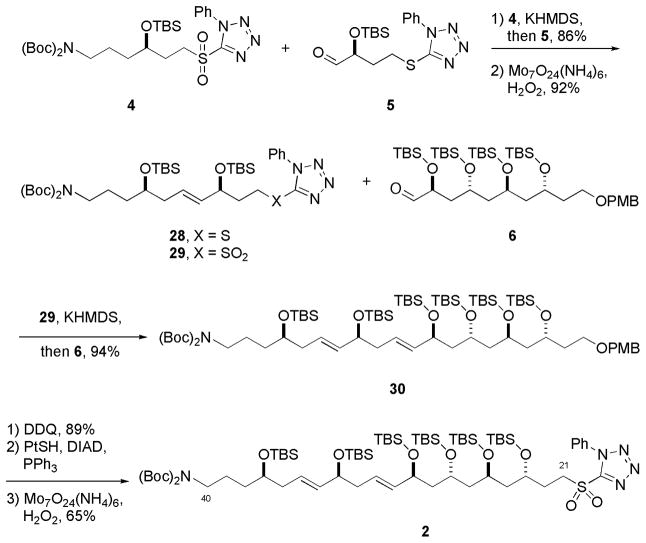

Large Bottom Fragment C21–C40

With all six fragments (4–9) in hand, the assembly of the bottom C21–C40 carbon framework of tetrafibricin was accomplished as shown in Scheme 6. Kocienski-Julia olefination of sulfone 4 with aldehyde 5 provided alkene 28 as the E-isomer in 86% yield. Oxidation of the sulfide to sulfone 29, followed by another Kocienski-Julia olefination this time with aldehyde 6 provided 30 as the E,E-isomer in 94% yield. Cleavage of the PMB-ether, then conversion of alcohol to the alkylthiophenyltetrazole, followed by oxidation of sulfide provided 2 in 58% yield over three steps.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the large bottom fragment C21–C40

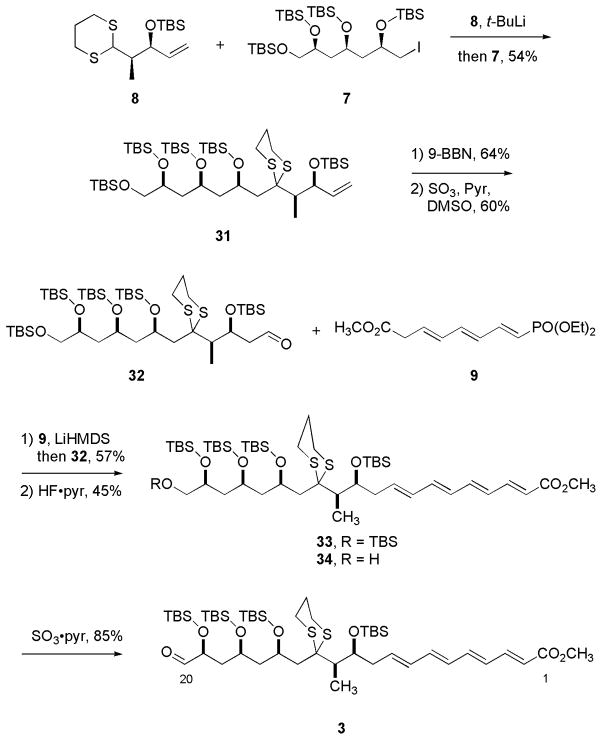

Large Top Fragment C1-C20

Synthesis of the C1–C20 fragment is shown in Scheme 7. Deprotonation of dithiane 8 with t-BuLi followed by addition of iodide 7 provided 31 in 54% yield. Hydroboration-oxidation of alkene 31 followed by oxidation of the corresponding alcohol provided aldehyde 32 in 38% yield for two steps. The formation of C8–C9 (E)-alkene was then carried out by deprotonation of phosphonate 9 with LiHMDS to generate an orange-colored anion, which was then reacted with aldehyde 32 to furnish the conjugated methyl ester 33 (JH8-H9 = 15.1 Hz) in 57% yield. The primary TBS-ether of 33 was cleaved with HF·pyr to provide the primary alcohol 34 in 45% yield. Oxidation of alcohol 34 to target aldehyde 3 was then carried out with SO3·pyr in 85% yield.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of the large top fragment 3 C1–C20.

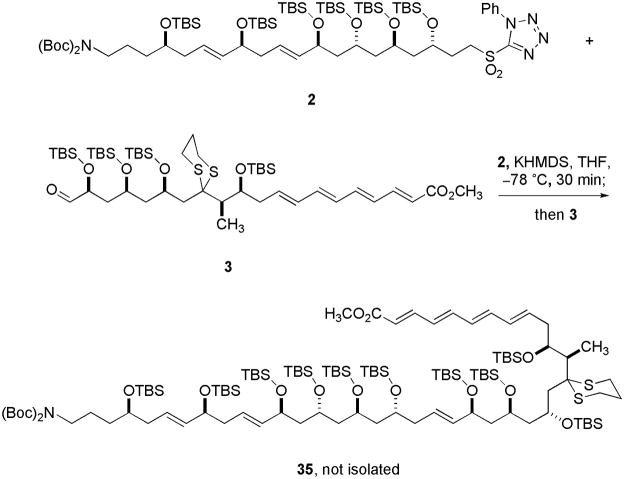

With two half fragments (C1–20 and C21–C40) of tetrafibricin in hand, Kocienski-Julia olefination of sulfone 2 with aldehyde 3 was attempted on several different scales (up to ~10 mg) and with different conditions (Scheme 8).18 Unfortunately, product 35 could not be isolated from any experiment. Neither sulfone 2 nor aldehyde 3 was recovered in substantial quantities.

Scheme 8.

Attempted coupling reactions

3. Conclusions

Efficient scalable and stereoselective syntheses of six main fragments (4–9) of tetrafibricin have been achieved. These fragments can potentially be assembled to make the natural product in several different ways. Here a highly convergent route was explored to couple three fragments each to make two large halves (C1–20 and C21–C40) of tetrafibricin. The reaction to couple these halves failed, so other orders of fragment coupling need to be pursued to make tetrafibricin. The availability of these fragments and the successful coupling reactions described herein will facilitate that work.

4. Experimental

Complete experimental details and compound characterization data along with copies of key spectra can be found in the thesis of Dr. V. Gudipati.18

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, for funding this work.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor Harry H. Wasserman in celebration of his 90th Birthday

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.(a) Kamiyama T, Umino T, Fujisaki N, Fujimori K, Satoh T, Yamashita Y, Ohshima S, Watanabe J, Yokose K. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1039–1046. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kamiyama T, Itezono Y, Umino T, Satoh T, Nakayama N, Yokose K. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1047–1054. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi Y, Czechitzky W, Kishi Y. Org Lett. 2003;5:93–96. doi: 10.1021/ol0272895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Satoh T, Yamashita Y, Kamiyama T, Watanabe J, Steiner B, Hadvary B, Arisawa M. Thromb Res. 1993;72:389–396. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90239-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Satoh T, Yamashita Y, Kamiyama T, Arisawa M. Thromb Res. 1993;72:401–409. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90240-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BouzBouz S, Cossy J. Org Lett. 2004;6:3469–3472. doi: 10.1021/ol048862i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lira R, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2007;9:533–536. doi: 10.1021/ol0629869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Gudipati V, Bajpai R, Curran DP. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 2009;74:774–783. doi: 10.1135/cccc2008195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang K, Gudipati V, Curran DP. Synlett. 2010:667–674. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1219376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friestad GK, Sreenilayam G. Org Lett. 2010;12:5016–5019. doi: 10.1021/ol1021417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakemore PR. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 2002;1:2563–2585. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AB, Adams CM. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:365–377. doi: 10.1021/ar030245r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaus SE, Brandes BD, Larrow JF, Tokunaga M, Hansen KB, Gould AE, Furrow ME, Jacobson EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1307–1315. doi: 10.1021/ja016737l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolaou KC, Fylaktakidou KC, Monenschein H, Li Y, Weyershausen B, Mitchell HJ, Wei H, Guntupalli P, Hepworth D, Sugita K. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15443–15454. doi: 10.1021/ja030496v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson MH, McDonald FE. Org Lett. 2004;6:1601–1604. doi: 10.1021/ol049630m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori N, Matsukura H, Matsuo G, Nakata T. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1853. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Garegg PJ, Samuelsson B. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1979:978–980. [Google Scholar]; b) Fuwa H, Okamura Y, Natsugari H. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:5341–5438. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funel JA, Pronet J. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4555–4558. doi: 10.1021/jo049557d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimura T, Yakushiji F, Kondo S, Wu X, Shindo M, Shishido K. Org Lett. 2006;8:475–478. doi: 10.1021/ol0527678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Mori Y, Asai M, Kawade J, Furukawa H. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:5315–5321. [Google Scholar]; b) Denmark S, Shinji F. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8971–8973. doi: 10.1021/ja052226d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudipati V. PhD Thesis. University of Pittsburgh; 2009. http://etd.library.pitt.edu/ETD/available/etd-04212008-115104/ [Google Scholar]