Abstract

Experimental data obtained with an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) rapid scan spectrometer were translated through the reverse transfer functions of the spectrometer hardware to the sample position. Separately, theoretical calculations were performed to predict signal and noise amplitudes at the sample position for specified experimental conditions. A comparison was then made between the translated experimental values and the calculated values. Excellent agreement was obtained.

Keywords: EPR, quantitation, rapid scan, signal-to-noise

1. Introduction

Quantitative EPR has long been recognized as difficult and subject to many confounding factors [1, 2]. Spin quantitation by EPR typically is done by comparison of signal intensity of an unknown to that of a standard sample under comparable conditions (see appendix E in [3]). In the present study the goal is to compare absolute experimental and theoretical signal and noise intensity. The spectrometer, the resonator, and the sample were characterized in detail, which then permits the measurement of any one of several free parameters that might otherwise be difficult to determine. These experiments also provide a theoretical foundation for spin quantitation. In each case one must first fully characterize a known system and check that the experimental data can be reconciled to values calculated from first principles. This study extends the approach of our prior studies of spin echo amplitudes [4, 5] to rapid scan EPR. The measurements were performed at 258 MHz because of interests in quantitative in vivo imaging.

2. Experiments

2.1 Characterization of the sample

The sample was a 0.43 mM aqueous solution of the nitroxyl radical 4-oxo-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy-d16 (CDN Isotopes, Quebec), abbreviated Tempone-d16. The sample was prepared gravimetrically and calibrated at X-band vs. a sample of Tempol (4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy), which can be prepared more accurately because the crystalline radical is commercially available in high purity (Aldrich Chemical, Milwaukee). The 0.43 mM Tempone-d16 solution was purged with N2 to remove O2, and flame-sealed.

2.2 Characterization of the resonator

The reflection resonator used in this study was locally constructed using 5 turns of AWG 38 (0.10 mm) wire with a variable capacitor in series with the coil for frequency adjustment and a fixed capacitor every 2.5 turns. The fixed capacitors are Voltronics, Series 5, nonmagnetic ceramic chip capacitors. The first is 5 pF and the second is 4 pF, in parallel with a Voltronics NMA4P3HC, 0.45 – 3 pF. The resonator is inductively coupled to the transmission line with a loop approximately 12 mm in diameter. The loop is moved to adjust coupling. The resonator i.d. and length are each 10 mm. Accounting for the wall thickness of the 10 mm o.d. sample tube, ca. 0.64 cm3 of sample was in the resonator. For the experiment described here the resonator was set to a frequency of 258.5 MHz and was critically coupled to the transmission line. The filling factor η was calculated based on the geometry of the sample and resonator, including the reentrant flux region between the resonator and the 25 mm shield. It was assumed that B1 is uniform in these regions. The calculated value of η is 0.653. The filling factor calculation uses the linearly polarized B1, but only one circularly polarized component creates the EPR signal. This factor of ½ is included explicitly in the calculation of Vs in section 3.1, rather than in the calculation of η. Resonator Q measured with a network analyzer was 42.

2.3 Characterization of the spectrometer

The rapid scan bridge, rapid scan coil driver [6], resonator assembly, and main magnet [7, 8] were locally designed and constructed. The digitizer, data collection software, main magnet power supply and field controller are from Bruker BioSpin. To fully characterize the total system, the gain and noise figure were measured.

2.3.1 Gain

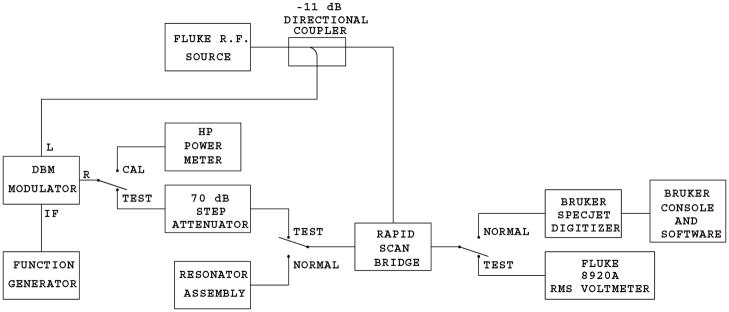

To quantitatively characterize the spectrometer, an end-to-end gain measurement was made from the resonator attachment point to the data recorded by the Bruker software. This gives the complete gain and loss information for all of the spectrometer components: low noise preamplifier (LNA), double-balanced mixer detection stages, video amplifier, programmable filter, digitizer and all cabling and connector losses. The measurement was made using the set up shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the paths for signal gain and noise measurements.

A small portion of the bridge r.f. source power was sampled using an 11 dB directional coupler, and bi-phase modulated using a double balanced mixer (DBM). The RF amplitude was set to a convenient level that kept the demodulated signal on-scale in the digitizer and was well below the level that produced distortion from saturation effects. The phase was modulated ± 180° with a square wave at approximately 30 kHz. The output of the DBM measured with an HP power meter was −1.36 dBm. The modulation was temporarily set to approximately 0.1 Hz, so that it could be observed that both states of the modulator produced the same power. The 30 kHz modulated signal was then highly attenuated by a calibrated 0 to 70 dB JFW step attenuator that was set to 70 dB to obtain a signal at −71.36 dBm (−101.36 dBw). This signal was then inserted into the spectrometer at the end of the cable that normally connects to the resonator. The switching indicated in Fig. 1 was accomplished by reconnecting cables.

The result was a demodulated square wave at 30 kHz at the final output of the Bruker software, the amplitude of which could be accurately measured with the software cursors. A full set of data at various video gain settings, LNA settings, r.f. frequencies and programmable filter gains was obtained to fully characterize the spectrometer, but only the data relevant to this particular quantitative EPR experiment are reported here, i.e. at 258.5 MHz, LNA gain = 20 dB, and video gain = 60 dB. To find the spectrometer gain the following calculations were made. First the power at the resonator port for the calibration set up was converted to Vin(rms):

| (1) |

where Z0 is the characteristic impedance of the transmission line, 50 ohms.

The end-to-end gain is

| (2) |

The Vin is expressed as a rms voltage because ultimately the EPR signal amplitude is derived from a power equation and is therefore expressed as a rms voltage. The Vout(p) measurement was made after adjusting the detector phase to maximize the signal amplitude. The measurement was made with a ±180° phase modulated signal to take out any d.c. offset in the system and to avoid the need to know where “zero” was in the output signal. Since it was verified that both states of the modulated DBM produce equal r.f. power levels, Vout(p) = Vpp/2. The value measured with the Bruker software cursor was converted into volts using the relationship Vpp = Cpp·fsv/(avg·fsc), where Cpp is the measured peak-to-peak Bruker counts, fsv is the full scale volts of the digitizer, avg is the number of averages, and fsc is the full scale counts of the digitizer. Substitution into Eq (2) gives Gv in terms of measurable quantities, which were the following: Cpp = 2.19×104, fsv = 0.5, avg = 100, fsc = 256.

| (3) |

The certainty in the gain was estimated to be ± 5% (± 0.4 dB). The principal contributions were uncertainty in the reference power and the changes in cable connections necessary to measure gain. The separately adjustable gain of the programmable filter was not included here, and must be added to obtain the total experimental gain.

2.3.2 Noise Figure

The noise figure was measured with a true RMS voltmeter and by a method that utilizes a calibrated noise source. The values obtained by both methods were in excellent agreement. The calibrated noise source can be used to characterize both gain and noise figure. The direct RMS voltmeter method is described here.

First, a thermal reference is required at the resonator port of the spectrometer. A 50 ohm load could be used, but loads usually are matched only to the −20 to −26 dB level. For this reason the resonator itself was used as the thermal reference because the resonator coupling can be adjusted to better than a −40 dB match, although in practice the coupling makes little difference in the noise. To insure that no source noise contributed to the thermal reference measurement, the incident power on the resonator was fully attenuated (50 dB), which reduces the phase noise contribution to below the thermal level.

The second part of the measurement was to connect a true RMS voltmeter (Fluke model 8920A) in place of the Bruker digitizer. The measurement was made with most spectrometer parameters set to the same values as used for the EPR measurement, including the 600 kHz setting for the programmable filter, which defines the bandwidth of the system. One parameter that was different was the source power, as discussed in the previous paragraph. In addition the noise measurement was made with the programmable filter gain set to +16 dB to better utilize the dynamic range of the RMS voltmeter. Since the filter was the last stage in the spectrometer, its noise figure does not contribute significantly to the overall noise figure. The measurement was made on the absorption channel because this channel was used for the quantitative EPR measurement. The absorption phase was found by temporarily setting the incident power to a high level so that a substantial phase noise contribution was evident in the meter reading. Then the detector phase was adjusted to minimize the phase noise contribution. Once the absorption phase was found, the incident power was returned to the highly attenuated setting. The meter then read the thermal noise at the spectrometer input, multiplied by the gain of the spectrometer, with an added component representing the noise contributed by the spectrometer electronics. The overall Noise Figure (NF) in dB is then given by:

| (4) |

where Nm was the noise power measured by the RMS voltmeter in dBm (−23.4 dBm); Ntin is the thermal noise power at the 50 ohm spectrometer input (−174 dBm + 10 log(BW); BW is the 600 kHz setting of the programmable filter times a noise equivalent bandwidth factor of 1.0262 which converts the nominal filter setting to a noise equivalent bandwidth for a 4-pole Butterworth low-pass filter; Gv is the overall spectrometer gain, (+70.97 dB, Eq. (3)); and Gf is the programmable filter gain (+16 dB).

Evaluating Eq. (4) for the experimental conditions yields NF = 5.73 dB. The uncertainty in this measurement was estimated to be ± 0.7 dB, which consisted primarily of the spectrometer gain uncertainty of ± 0.4 dB (Eq. (3)), plus uncertainties in the voltmeter calibration, and the gain of the programmable filter.

2.4 Translation of experimental values of signal and noise to the sample position

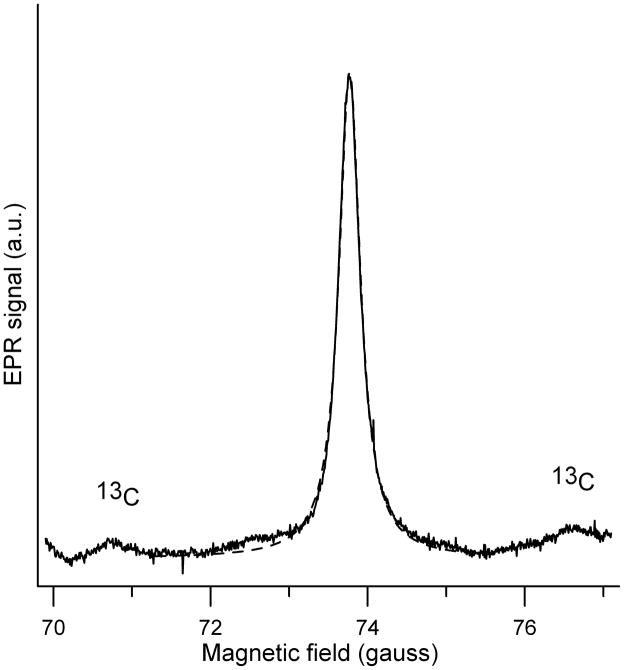

A rapid scan experiment [9] was performed on the 0.43 mM nitroxyl sample at a slow scan rate so that deconvolution of the recorded spectrum was not required to recover an accurate measurement of the absorption amplitude. Calculations were performed for a 7.2 G scan centered on the low-field nitrogen hyperfine line (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

7.2 G rapid scan of the low-field nitrogen hyperfine line of 0.43 mM Tempone-d16 obtained with 1 kHz sweep frequency and averaged 40960 times. The data acquisition time was about 40 s, using Bruker XEpr software. The 13C hyperfine lines with a splitting of 5.9 G are well defined. The dashed line is a Lorentzian with full width at half height of 330 mG.

2.4.1 Translation of measured signal to the resonator

The measured rapid scan absorption signal amplitude was 5.5 × 104 counts (Cts) after 40960 averages, which was converted to signal voltage at the digitizer input using Vsd = Cts· Fsv/(avg·fsc) volts. Signal increases linearly with the number of scans, so the choice of 40,960 scans was arbitrary. The signal voltage at the resonator, Vsr = Vsd/Gv, evaluated for the experimental conditions was then:

| (5) |

Vsr is the rms value of the EPR r.f. signal at the resonator after coupling to the transmission line. At this stage in the calculation, more figures than are justified by experimental uncertainty are carried to avoid roundoff errors.

2.4.2 Translation of measured noise to the resonator

The measured noise (Nm) at the input to the digitizer under the experimental conditions was −39.2 dBm. Measurement of the noise with a meter, prior to the digitizer, avoids complications from coherent noise in the digitizer or subjective judgments concerning which segment of baseline to use in estimating noise. Expressed in dBm, the measured noise power at the digitizer input translated to the resonator (Npr) using results from Eq. (3) and (4) was:

| (6) |

The Npr can be expressed as voltage:

| (7) |

The noise voltage at the resonator (Nvr) consists of thermal noise and a small contribution from phase noise from the source. For the experimental power level phase noise was independently measured to be 0.5 dB above the thermal noise level.

2.4.3 Ratio of measured signal and measured noise translated to the resonator

Combining the results in Eq. (5) and (7) gives the signal to noise ratio, S/N,

| (8) |

3. Calculations of theoretically expected signal and noise from first principles

As discussed in [5, 10, 11] the d.c. susceptibility, χo, for S = ½ can be expressed as

| (9) |

where N0 is the number of spins per unit volume, γ is the magnetogyric ratio, ħ is Planck’s constant, μ0 is the permeability of a vacuum, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the temperature of the sample. χ″ is the imaginary component of the effective RF susceptibility, and results in absorption of energy from the RF field. The area under the EPR absorption is proportional to susceptibility. Since EPR S/N is expressed in terms of peak heights rather than peak areas, calculations of theoretical expressions for signal voltage require introduction of lineshape parameters. At resonance [12] (p. 52), χ″ = χ0ω0/Δω, where the denominator is a “line width parameter” equal to 1/πgmax where gmax is the maximum value of the line shape function, g(ω − ω0), for a relaxation-determined Lorentzian absorption line, with full width at half height = Δω. Substitution into Eq. (9) of T = 298 K and values of the fundamental constants gives

| (10) |

Experimentally, unresolved hyperfine and/or anisotropy that is incompletely averaged by molecular dynamics result in EPR lines that have a Gaussian component in addition to the relaxation-determined Lorentzian component. The S/N measurement uses the peak amplitude of the absorption spectrum, so the formulae used here include a numerical coefficient that corrects peak heights of the absorption line for combinations of Gaussian and Lorentzian lineshapes. If the line is purely Lorentzian, the coefficient is 0.637, and if Gaussian, 0.939 [13]. Thus, estimating the line shape itself can have as much as 50% impact on the predicted S/N. Unresolved hyperfine couplings to the 2H of Tempone-d16 are small relative to the relaxation determined linewidth, so experimental spectra at 258.5 MHz could be simulated using a nearly completely Lorentzian lineshape. The full width at half height of the rapid scan absorption signal is 330 ± 10 mG (Figure 2). Based on substitution into Eq. (10) and conversion to angular frequencies, χ″ for one of the three lines of the absorption spectrum of the 0.43 mM Tempone-d16 solution is:

| (11) |

3.1 Signal voltage

Based on the information about the sample, resonator, and incident power, VS, the CW EPR signal voltage at the end of the transmission line connected to the resonator, can be calculated using Eq. (12) (from [5]), corrected for the factor of ½ described in section 2.2,

| (12) |

where η (dimensionless) is the resonator filling factor; Q (dimensionless) is the loaded quality factor of the resonator, Z0 is the characteristic impedance of the transmission line (in ohms) = 50 ohms; P is the microwave power (in W) to the resonator produced by the external microwave source. For this experiment Q = 42 and η = 0.653 (see resonator characterization, section 2.2).

The experimental S/N is the ratio of the maximum signal amplitude to the rms noise. The calculation of S/N includes a value for the thermal noise power. The resultant noise voltage is an rms value, which is appropriate for the denominator of the S/N calculation. Vs also is expressed in terms of microwave power,

| (13) |

3.2 Noise

Thermal noise power (in W) for 600 kHz bandwidth is Pn = −204 + 10 log(6×105) = −146.22 dBw. The phase noise from the source, at the power used in the S/N measurement, was 0.5 dB, so 0.5 was added to the thermal noise for a total noise of −145.72 dBw, which is 2.68×10−15 W. The noise voltage, Vn, which is needed for comparison with signal voltage, is calculated as in Eq. (14)

| (14) |

Inclusion of the noise equivalent bandwidth (NEB) of the Krohn-Hite filter would increase the 600 kHz bandwidth by a factor of 1.026, resulting in Vn = 3.71×10−7 V.

3.3 Calculated S/N

Based on the results in Eq. (13) and (14) the S/N calculated for comparison with the experimental results is 7.11 × 10−7/3.71 × 10−7 = 1.92.

4. Summary: Comparison of theoretical and experimental S/N

The calculation of signal and noise in the prior section yields a S/N = 1.92 for the 0.43 mM Tempone-d16 sample at 258.5 MHz. The experimental measurement was S/N = 2.07, in almost perfect agreement (probably fortuitously so). It should be noted that although the S/N agreement is unexpectedly good, the experimental measurements of both signal and noise are both about 4% lower than the theoretical values. This is attributed to errors in characterizing the bridge gain and noise figure and the fact that these values are interdependent.

The experiment and calculation demonstrate the ability to fully characterize a spectrometer, resonator, and sample system. For the resonator used in these experiments it was reasonable to assume that B1 was uniform. However for other resonators B1 may not be uniform, which makes calculation of filling factor more difficult. If, however, the spectrometer hardware, software, and sample can be adequately characterized with one resonator, with a carefully calculated filling factor as demonstrated in this study, then a second resonator with an unknown filling factor could be studied to determine its filling factor, if filling factor were the only free parameter in the second measurement.

Acknowledgments

Development of rapid scan EPR is supported by NIH NIBIB grant R01EB000557 and is a collaborative project of the Center for EPR Imaging in Vivo Physiology supported by NIH NIBIB P41 EB002034 (Howard Halpern, PI). The authors thank postdoctoral associate Tomasz Czechowski for his preliminary work on this project, and Joshua Biller for assistance in some of the data collection.

References

- 1.Hyde JS. Experimental Techniques in EPR. Varian Associates Instrument Division; Palo Alto, CA: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alger RS. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Techniques and Applications. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1968. p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weil JA, Bolton JR, Wertz JE. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practical Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Frequency Dependence of EPR Signal Intensity, 250 MHz to 9.1 GHz. J Magn Reson. 2002;156:113–121. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2002.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Harbridge JR, Song R, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Frequency Dependence of EPR Signal-to-Noise. J Magn Reson. 1999;140:218–227. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quine RW, Czechowski T, Eaton GR. A Linear Magnetic Field Scan Driver. Conc Magn Reson B (Magn Reson Engin) 2009;35B:44–58. doi: 10.1002/cmr.b.20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. 250 MHz Crossed Loop Resonator for Pulsed Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Magn Reson Engineer. 2002;15:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Barth ED, Pelizzari CA, Halpern HJ. Magnet and Gradient Coil System for Low-Field EPR Imaging. Magn Reson Engineer. 2002;15:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi JP, Ballard JR, Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton GR. Rapid-Scan EPR with Triangular Scans and Fourier Deconvolution to Recover the Slow-Scan Spectrum. J Magn Reson. 2005;175:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Song R, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Absolute EPR Spin Echo and Noise Intensities. J Magn Reson. 1999;140:69–83. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Poole CP, Jr, Farach HA. Sensitivity in ESR Measurements. Handbook of Electron Spin Resonance. 1999;2:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingram DJE. Biological and Biochemical Applications of Electron Spin Resonance. Plenum Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weil JA, Bolton JR. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practical Applications. John Wiley Hoboken; New Jersey: 2007. p. 316. [Google Scholar]