Abstract

North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) were found in an important nineteenth century whaling area east of southern Greenland, from which they were once thought to have been extirpated. In 2007–2008, a 1-year passive acoustic survey was conducted at five sites in and near the ‘Cape Farewell Ground’, the former whaling ground. Over 2000 right whale calls were recorded at these sites, primarily during July–November. Most calls were northwest of the historic ground, suggesting a broader range in this region than previously known. Geographical and temporal separation of calls confirms use of this area by multiple animals.

Keywords: right whales, acoustic survey, seasonal occurrence, whale calls, Cape Farewell

1. Introduction

The North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is among the rarest cetaceans in the world, and is in danger of extinction despite more than 75 years of international protection [1,2]. The current best estimate of the population is fewer than 450 individuals [3], and the eastern population is widely regarded as extinct or nearly so [1,4]. Despite recent increases in western North Atlantic calf production, this population does not appear to be recovering, with anthropogenic factors—notably, vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglement [5]—responsible for significant numbers of deaths [2,6]. Whales from the western stock are most frequently seen off the eastern North American coast from Florida to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence [7,8]. Surveys in this range are conducted relatively often, but despite intensive survey effort, many individuals are not seen during summer months, and winter locations of much of the population remain unknown [9]. In addition, pelagic areas have received little dedicated survey effort [10]. This species' precarious status necessitates a thorough understanding of right whale summering and wintering grounds if protective measures, such as modification of fishing practices or changes in vessel traffic patterns, are to be effective.

One promising possibility for a right whale summering area is the Cape Farewell Ground (CFG), an area 400–500 km east of southern Greenland, where right whales were hunted during the late 1800s [11,12]. However, because this remote area experiences difficult weather conditions for visual surveys, little sighting effort has been made there [13]. In the last 50 years, only two confirmed right whale sightings were made on the CFG, both of individually identified females—one seen rarely, and the other not at all, in the well-known western North Atlantic habitats [9,10]. An additional observation of two animals tentatively identified as bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) was made in 1979 [14], though these may have been right whales [11]. In addition, right whales have occasionally been sighted in coastal waters west and east of Iceland [9,13]. Although North Atlantic right whales once occurred in the CFG and adjacent waters, the extent and seasonality in which they are now present have been unknown.

In recent years, acoustic surveys have been used to monitor cetacean populations in remote areas difficult to investigate by visual surveys alone. Right whales are appropriate for acoustic surveys: solitary North Atlantic animals can produce up to 10 vocalizations per hour, and groups up to 60 vocalizations per hour or more [15]. Autonomous hydrophones have been successfully used to search for right whales in high-use areas (e.g. Cape Cod Bay [16] and the Great South Channel), places they occur infrequently (e.g. Gulf of Alaska [17]), or areas where they were sighted by whalers historically (e.g. Scotian Shelf [18,19]). The purpose of this study was to acoustically monitor the CFG, a remote area of historical importance to this highly endangered species.

2. Material and methods

In July 2007, five autonomous hydrophone instruments [20] were deployed in the area east of southern Greenland and southwest of Iceland. One instrument was located in the CFG (figure 1), with the rest being placed north and east of this area. All hydrophones were moored at a depth of approximately 800 m in waters over 1500 m deep and were programmed to record ambient sound continuously in the 1–920 Hz band, a range that includes calls of North Atlantic right whales [21]. The instruments were retrieved in July 2008 and returned for laboratory analysis.

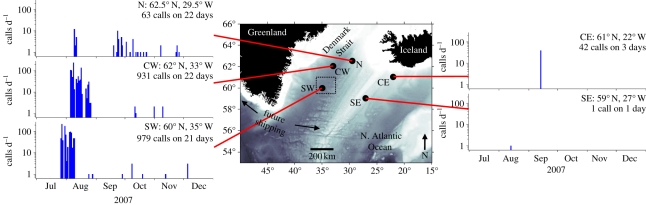

Figure 1.

Locations of passive acoustic moorings near Iceland and southern Greenland (black spots), and the number of right whale upcalls detected per day in late 2007 at the five sites. The rectangular dotted box is the approximate location of the Cape Farewell Ground, as defined by historical catches, and arrows indicate a shipping route that will open when the Northwest Passage becomes reliably ice-free. In ocean areas, depth of colour indicates bathymetry.

Data analysis focused on right whale upcalls, as these are commonly produced by both males and females [21–23]. Recordings were processed using automatic call-recognition software [24,25] for detecting upcalls, configured with a low detection threshold so as to miss few, if any, calls. Trained analysts checked all detections to confirm their validity. Right whale upcalls are readily distinguished from most other marine sounds, although on occasion humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) make upsweeping vocalizations similar to upcalls. Criteria used to unambiguously distinguish right whale upcalls and humpback vocalizations included: (i) humpback sounds usually occur with other frequency-modulated sounds; (ii) humpback sounds often recur with a period of 3–5 s, while right whale upcalls have a longer, more irregular inter-call interval; and (iii) right whale gunshot sounds [21] often occur in conjunction with upcalls.

3. Results

A total of 2012 upcalls were found (figure 1), with the earliest on 26 July 2007 at the southwest site (60° N, 35° W), and the latest that year on 5 December 2007 at the same site. The sites with the most calling were the ones nearest the CFG, with 931 calls at the CW site (62° N, 33° W) and 979 calls at the SW site. The north (N) site (62.5° N, 29.5° W) had 63 calls, and the centre east (CE; 61° N, 22° W) and southeast (SE; 59° N, 27° W) sites combined had 43 calls. Calls were also detected the next season on 8 July 2008 at the SW site but were not recorded beyond this date as the instruments were retrieved shortly thereafter. The numbers of recorded calls increased to 10–100 calls per day in late July at the SW site, in early August at the centre west (CW) site and later in August at the N site. After a gap in calling of over a month, many calls were again recorded at the N site from late September through to late October, and at the CW site in late October. This pattern suggests that calling whales moved from the southwest towards the northeast starting in late July, and then back southwestward again beginning in September. If whales are indeed moving in this manner, we can define a whale passage as one or more successive days in which right whale upcalls occurred, separated from other days with calls by at least 24 h without calls. Using this definition, the N site had the most whale passages in a season, with 17 separate passages in September–November 2007. In addition, on 9 August 2007, right whale upcalls were recorded on three hydrophones within a span of 7 h. Given the source level of these calls and the distance between hydrophones (190 km), this indicates that there were at least three vocalizing right whales within the array during this time. Maximum detection distances are unknown, but are probably comparable to or less than those of humpback whales, estimated at 45 km [26].

4. Discussion

These results confirm that a historically important area for this highly endangered species continues to be used in many months by a portion of the remaining population, and broadens the known range of occurrence in this area. Calling patterns indicate that animals arrived in the area in July, moved northeast of the historic CFG, then returned southwest in autumn. This agrees with known movements of many right whales off North America—moving north and east in spring and early summer, then returning south and west in the autumn [8]—suggesting that these whales come from either this population or another population with temporally similar seasonal movements.

We recorded over 2000 upcalls, but because of the remote nature and geometry of this array and variation in calling rates [21], the number of whales in the area is unknown. However, we recorded numerous upcalls over many months (July–November), calls were recorded nearly simultaneously on three hydrophones, and 17 ‘whale passages’ were deduced. Evidence of even a few whales summering near this former whaling ground is an important finding for this species, and shows the value of acoustic surveys for endangered cetaceans in remote or understudied locations.

Information on right whale seasonal occurrence has been used to guide conservation actions intended to prevent ship strikes, including the movement of shipping lanes [27] and vessel speed restrictions [28]. Ships commonly pass south of Greenland when transiting between Europe and North America [29], and the Northwest Passage to the north of North America is expected to become ice-free and open to shipping well within the century [30]. Ships on these routes pass just south of the CFG and transect the migratory route of any right whales that occupy the region (figure 1).

The confirmation of right whale seasonal presence on the CFG and adjacent waters is an important finding for the conservation of this endangered species. Additional information, particularly genetic and photo-identification data, will be essential to confirm the stock from which these animals originate and to evaluate the threats posed by existing and future shipping and fishing activity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Haru Matsumoto for autonomous hydrophone design, Matt Fowler and the Icelandic Coast Guard cutter Ægir for instrument deployment/recovery, and Susan Parks and Sofie Van Parijs for assistance with right whale calls. Funding was provided by NOAA Ocean Exploration grant NA06OAR4600100 and US Navy grants N00244-08-1-0029, N00244-09-1-0079 and N00244-10-1-0047. This is PMEL contribution no. 3282.

References

- 1.Clapham P. J., Young S. B., Brownell R. L., Jr 1999. Baleen whales: conservation issues and the status of the most endangered populations. Mamm. Rev. 29, 35–60 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraus S. D., et al. 2005. North Atlantic right whales in crisis. Science 5734, 561–562 10.1126/science.1111200 (doi:10.1126/science.1111200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettis H. 2009. 2009 Annual Report Card Addendum. Boston, MA: North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium [Google Scholar]

- 4.Notarbartolo di Sciara G., Politi E., Bayed A., Beaubrun P., Knowlton A. 1998. A winter cetacean survey off southern Morocco with special emphasis on right whales. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 48, 547–550 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson A. J., Salvador G. S., Kenney J. F., Robbins J., Kraus S. D., Landry S. C., Clapham P. J. 2005. Fishing gear involved in entanglements of right and humpback whales. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 21, 635–645 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01256.x (doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01256.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowlton A., Kraus S. 2001. Mortality and serious injury of northern right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in the western North Atlantic Ocean. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. (Special Issue) 2, 193–208 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraus S. D., Rolland R. M. 2007. Right whales in the urban ocean. In The urban whale (eds Kraus S. D., Rolland R. M.), pp. 1–39 Cambridge, MA: Harvard [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown M. W., Fenton D., Smedbol K., Merriman C., Robichaud-LeBlanc K., Conway J. 2009. Recovery strategy for the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) in Atlantic Canadian waters. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, vi + 66 pp. Fisheries and Oceans Canada [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton P. K., Knowlton A. R., Marx M. K. 2007. Right whales tell their own stories: the photo-identification catalog. In The urban whale (eds Kraus S. D., Rolland R. M.), pp. 75–104 Cambridge, MA: Harvard [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown M. W., Kraus S. D., Slay C. D., Garrison L. P. 2007. Surveying for discovery, science, and management. In The urban whale (eds Kraus S. D., Rolland R. M.), pp. 105–137 Cambridge, MA: Harvard [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves R. R., Mitchell E. 1986. American pelagic whaling for right whales in the North Atlantic. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. (Special Issue) 10, 221–254 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeves R. R., Smith T. D., Josephson E. A. 2007. Near-annihilation of a species: right whaling in the North Atlantic. In The urban whale (eds Kraus S. D., Rolland R. M.), pp. 39–74 Cambridge, MA: Harvard [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowlton A., Sigurjónsson J., Ciano J. N., Kraus S. D. 1992. Long-distance movements of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis). Mar. Mamm. Sci. 8, 397–405 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1992.tb00054.x (doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1992.tb00054.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonsgård Å. 1981. Bowhead whales, Balaena mysticetus, observed in arctic waters of the eastern North Atlantic after the second World War. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. 31, 511 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews J. N., et al. 2001. Vocalisation rates of the North Atlantic right whale. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 3, 271–282 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark C. W., Brown M. W., Corkeron P. 2010. Visual and acoustic surveys for North Atlantic right whales, Eubalaena glacialis, in Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts, 2001–2005: management implications. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 26, 837–854 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00376.x (doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00376.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mellinger D. K., Stafford K. M., Moore S. E., Munger L., Fox C. G. 2004. Detection of North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) calls in the Gulf of Alaska. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 20, 872–879 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01198.x (doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01198.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell E., Kozicki V. M., Reeves R. R. 1986. Sightings of right whales, Eubalaena glacialis, on the Scotian Shelf, 1966–1972. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. (Special Issue) 10, 83–107 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellinger D. K., Nieukirk S. L., Matsumoto H., Heimlich S. L., Dziak R. P., Haxel J., Fowler M., Meinig C., Miller H. V. 2007. Seasonal occurrence of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) at two sites on the Scotian Shelf. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 23, 856–867 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00144.x (doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00144.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox C. G., Matsumoto H., Lau T. K. A. 2001. Monitoring Pacific Ocean seismicity from an autonomous hydrophone array. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 4183–4206 10.1029/2000JB900404 (doi:10.1029/2000JB900404) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parks S. E., Tyack P. L. 2005. Sound production by North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in surface active groups. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 3297–3306 10.1121/1.1882946 (doi:10.1121/1.1882946) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald M. A., Moore S. E. 2002. Calls recorded from North Pacific right whales (Eubalaena japonica) in the eastern Bering Sea. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 4, 261–266 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark C. W. 1982. The acoustic repertoire of the southern right whale, a quantitative analysis. Anim. Behav. 30, 1060–1071 10.1016/S0003-3472(82)80196-6 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(82)80196-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellinger D. K., Clark C. W. 2000. Recognizing transient low-frequency whale sounds by spectrogram correlation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 107, 3518–3529 10.1121/1.429434 (doi:10.1121/1.429434) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellinger D. K. 2001. Ishmael 1.0 user's guide. Technical report no. OAR-PMEL-120, NOAA/PMEL, Seattle [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stafford K. M., Mellinger D. K., Moore S. E., Fox C. G. 2007. Seasonal variability and detection range modeling of baleen whale calls in the Gulf of Alaska, 1999–2002. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122, 3378–3390 10.1121/1.2799905 (doi:10.1121/1.2799905) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderlaan A. S. M., Taggart C. T., Serdynska A. R., Kenney R. D., Brown M. W. 2008. Reducing the risk of lethal encounters: vessels and right whales in the Bay of Fundy and on the Scotian Shelf. Endang. Species Res. 4, 283–297 10.3354/esr00083 (doi:10.3354/esr00083) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Federal Register 2008. Final rule to implement speed restrictions to reduce the threat of ship collisions with North Atlantic right whales. Fed. Regist. 73, 60 173–60 191 Office Fed. Regist., College Park, MD [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arctic Council. 2009. Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment Report 2009. Tromsø, Norway: Arctic Council.

- 30.Wang M., Overland J. E. 2009. A sea ice free summer Arctic within 30 years? Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L07502. 10.1029/2009GL037820 (doi:10.1029/2009GL037820) [DOI] [Google Scholar]