Abstract

One of the greatest impacts on in vitro cell biology was the introduction of three-dimensional (3D) culture systems more than six decades ago and this era may be called the dawn of 3D-tissue culture. Although the advantages were obvious, this field of research was a “sleeping beauty” until the 1970s when multicellular spheroids were discovered as ideal tumor models. With this rebirth, organotypical culture systems became valuable tools and this trend continues to increase. While in the beginning, simple approaches, such as aggregation culture techniques, were favored due to their simplicity and convenience, now more sophisticated systems are used and are still being developed. One of the boosts in the development of new culture techniques arises from elaborate manufacturing and surface modification techniques, especially micro and nano system technologies that have either improved dramatically or have evolved very recently. With the help of these tools, it will soon be possible to generate even more sophisticated and more organotypic-like culture systems. Since 3D perfused or superfused systems are much more complex to set up and maintain compared to use of petri dishes and culture flasks, the added value of 3D approaches still needs to be demonstrated.

Keywords: Three-dimensional cell culture, Micro-bioreactors, Chips, Scaffold, Perfusion

INTRODUCTION

Since Petri published his methodology of growing bacteria in flat glass dishes in 1887[1], scientists have used this culture format for growing, not only prokaryotes, but all kinds of eukaryotic cells and tissues. Even if this culture technique is simple and convenient in daily cell culture routines, it is undisputable that growing cells on flat substrates is insufficient to reflect complex systems like tissues or whole organs. With this consideration, the introduction and systematic characterization of new culture techniques, generating spherical aggregates of isolated embryonic cells by Holtfreter in 1944[2] and Moscona in 1952[3-5], revealed new insights in tissue morphogenesis and opened a new chapter in cell culture technique. During the following years, studies on cell aggregates were extended to the research field of tumor biology and were advanced in the 1970s by Sutherland et al[6], who used “multicellular spheroids” as a tumor model for radiation experiments. Three-dimensional (3D)-culture models more closely resemble the in vivo situation concerning cell shape and the microenvironment. Compared to traditional monolayer techniques, it was shown that three-dimensionality is able to restore and maintain the differentiated status of adult cells, such as hepatocytes[7-9], cardiac myocytes[10,11], chondrocytes[12,13], and endocrine pancreatic islet cells[14] in vitro. Moreover, this culture configuration was applied to the study of the growth and differentiation of progenitor cells such as osteoblasts[15,16], hematopoietic progenitor cells[17], and embryonic and mesenchymal stem cells[18-23]. More importantly, a considerable amount of stem or progenitor cell cultivation techniques require, at least temporarily, aggregation into embryoid bodies for proper differentiation[24].

STATE OF THE ART OF 3D-CULTURE SYSTEMS

Systematic analysis of various cell types in conventional monolayer- and 3D-culture revealed that parameters like spatial and temporal gradients of soluble factors (growth factors, cytokines and hormones), homologous and heterologous cell-cell contacts, cell-matrix interactions, which are undoubtedly coupled with the molecular and physical properties of the matrix, mechanical forces like fluid flow, as well as surface topography and chemistry of the cell culture substrate are of particular importance for cellular behavior in vitro[25-30]. Based on this knowledge, numerous 3D-culture systems have been developed to restore and maintain or induce cellular differentiation in vitro: (1) explant cultures of tissue slices or perfused whole organs, which retain tissue architecture; (2) cultivation of reaggregated cells (e.g. spheroids, embryoid bodies) or simple micro-mass cultures in which isolated cells are pelleted; (3) three-dimensional cultivation of isolated cells embedded in gels or immobilized on porous matrices in stationary culture; and (4) systems using micro-bioreactors for high density 3D-cultures with active nutrient and gas supply. In the remainder of this manuscript, only the latter two systems, using isolated cells together with synthetic scaffolds in 3D culture configurations, will be discussed in detail.

3D-MATRICES

One frequently used culture technique is to entrap cells in natural or synthetic hydrogels consisting of extracellular matrix (ECM) components (e.g. collagen, laminin, Matrigel, hyaluronic acid), natural polymers like alginate and chitosan or synthetic polymers comprising polyethylene glycol, synthetic self-assembling peptides or artificial DNA molecules[31,32]. Due to their mechanical and biochemical properties, hydrogels mimic the nature of soft tissues and provide a 3D network for cell-matrix interactions. Furthermore, the vast number of biocompatible natural and synthetic materials, which can be utilized in combination, turns hydrogels into many useful 3D-substrates. However, as hydrogels lack a distinct porous structure corresponding to blood and lymphatic vessels, mass transport in gels depends on slow diffusion through the gel and consequently leads to the formation of gradients of oxygen, nutrients, metabolites, and soluble factors (e.g. growth factors, hormones) within the gel-matrix. Therefore, gel-based systems without any forced medium flow are limited to rather small setups, at least in one dimension, as exemplified by several thin gel sandwich constructs or very low densities of cells with low metabolism-like cartilage[33]. The lack of mechanical stability of gel based tissue models often hampers the use of preformed tissues for implantations, especially if a certain load bearing is needed with the beginning of the in vivo application. Therefore, approaches to culture cells in a 3D configuration in combination with porous 3D-matrices based on sponge-like structures, usually prepared from biodegradable polymers, became attractive. Sponge-like structures exhibit larger pores than pure hydrogels and thus facilitate cell seeding and colonization of the substrates. Important parameters for their application in cell culture are the number of pores, pore size, as well as interconnectivity and distribution of the pores[31]. If the fenestrations are smaller than the cell size or the interconnectivity of the pores within the scaffold is poor, cell migration into the 3D-matrix is limited and thus cell distribution is restricted to near-surface layers of the substrate. Instead, perfused open porous foams from polylactic-co-glycolic acid that are collagenized and inoculated with immortalized bovine capillary endothelial cells and a hepatoma cell line (C3A), show a spatial separation upon in vitro culture; endothelial cells invade the foam completely whereas the hepatoma cells form a dense layer on the inflow side of the spongeous matrix (Figure 1).

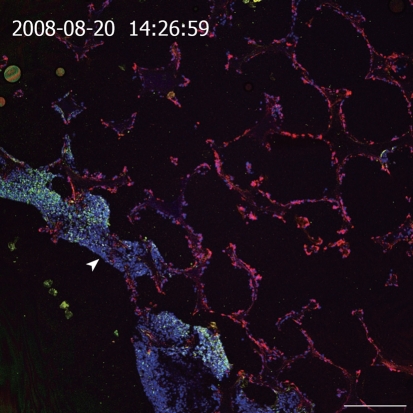

Figure 1.

Cross section of a resin embedded co-culture of a hepatoma cell line (C3A) and immortalized BCE in polylactic-co-glycolic acid foam. Medium inflow from the lower left side into the polymer foam (arrowhead). Staining of cytokeratin 18 (green, C3A cells), vimentin (red, BCE cells), Draq5 nuclear stain (blue, both cell types). Scale bar: 250 μm.

Depending on the cell type and pore size, a monolayer formation within the scaffold can be observed. Thus, optimal size and interconnectivity of the pores may vary and must be determined for each cell type used. Although a variety of materials can be used to produce porous sponge-like scaffolds, the most common are natural polymers often used for hydrogels (e.g. alginate, chitosan, collagen), synthetic polymers like polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid and their copolymers or composite material[31]. Experiments in our laboratory with the hepatoma cell line HepG2 in alginate sponges revealed that, despite a larger pore size compared to hydrogels, mass transport between sponge and culture medium was limited in stationary culture conditions (unpublished data).

Another approach to culture cells in a 3D configuration came along with new technologies for scaffold fabrication that comprises the immobilization of cells in fibrous 3D-matrices. Fibrous scaffolds can be produced in an electrospinning process that allows the creation of micro- and nano-fibers from a polymer solution and the subsequent deposition of a non-woven fibrous mesh on a collector[34,35]. This technique allows the fabrication of two dimensional or 3D-matrices depending on the thickness of the deposited fiber network on the collector. Fiber diameter can range from 3 nm to greater than 5 μm[34] and therefore electrospun nanofibers reflect, in part, the fibrous structure of natural extracellular matrix components. Commonly used materials for nanofiber scaffolds are synthetic polymers like polylactic-co-glycolic acid, poly-L-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone, poly- ε-caprolactone, polyamide and natural polymers like collagen, elastin, fibrinogen, alginate or hyaluronic acid or even combinations thereof[34]. One example of 3D tissue culture scaffolds is based on electrospun biodegradable aliphatic polycarbonates comprising photochemical post-treatments[36]. These scaffolds exhibit important advantages when compared with foams since the interconnectivity of voids available for tissue ingrowth is perfect. This is realized by a photopatterning of the non-woven fabric selectively lowering the molecular weight of the used polymer and, in turn, speeding up biodegradation. Within a couple of days, voids are formed in the scaffold, opening ways for increased perfusion and tissue/vessel ingrowth. In addition, ultrathin fibers produced by electrospinning offer an unsurpassed surface to volume ratio among applied tissue scaffolds. This has important consequences on the availability and presentation of polymer bound signaling molecules and on degradation rates of biodegradable scaffolds. Finally, electrospinning offers new 3D scaffolds with double length scale features with combinations of microfibers and electrospun nanofibers[37].

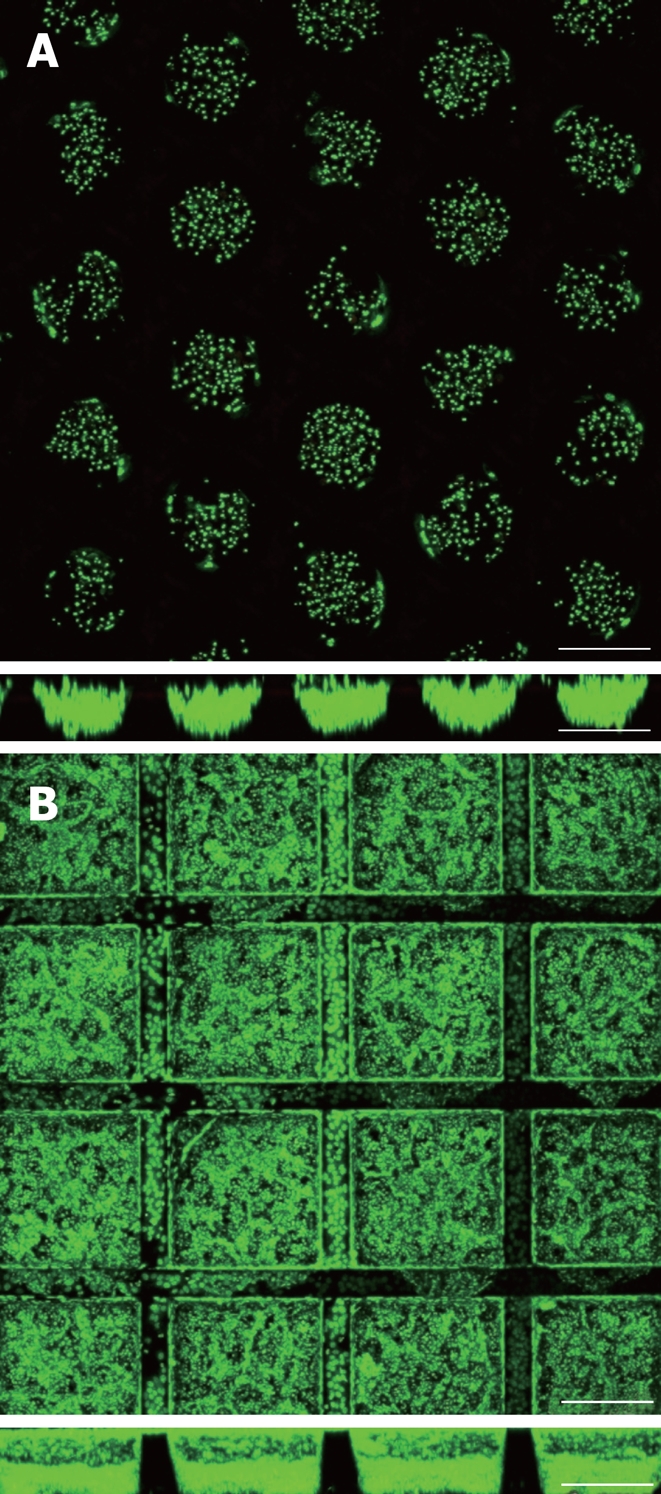

In contrast to the above mentioned techniques, we use a culture system developed at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology that is based on a microstructured polymer chip that serves as a scaffold for the 3D cultivation of cells[38-41]. Currently, the chip is manufactured in two different designs varying mainly in geometry and the manufacturing process. The so-called cf-KITChip has outer measures of 20 mm × 20 mm and a central grid-like microstructured area of 10 mm × 10 mm to 14 mm × 14 mm with cubic microcavities in which cells can organize into multicellular aggregates (Figure 2B). The cavities of the chips are open to the top and are 300 μm in each direction (w × l × d). However, the size and the shape of the microcavities can be adjusted to experimental needs. The bottom of the chip consists of a track etched polycarbonate (PC) membrane (10 μm thickness) with a high pore density (2 × 106 pores per cm²) and a pore size of 3 μm. Thus, mass exchange by diffusion through the membrane is facilitated and cell migration onto the back of the chip is prevented at the same time. The manufacturing process comprises a microreplication technique, such as microinjection molding or vacuum hot embossing of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) or polycarbonate (PC), to produce the container array of the scaffold and a solvent-vapor-welding technique to bond the perforated membrane to the back of the chip. The so-called r-KITChip represents another variant of the polymer chip. It differs in its current design from the cf-KITChip by the round geometry of the microcavities and the fabrication process called SMART (Substrate Modification and Replication by Thermoforming), which allows the production of chips from thin polymer films[42,43]. SMART consists of a combination of microtechnical thermoforming or microthermoforming and various material modification techniques, and thus allows a site-specific functionalization of 3D cavities. By the combination of microthermoforming and ion track technology, for instance, highly porous thin-walled microcavity arrays can be produced. Compared to hydrogels and nanofibrous or sponge-like scaffolds, the uniform geometry of the microstructured polymer chip allows the formation of cell aggregates with defined size in the microcavities (Figure 2). This is of particular importance in terms of a homogenous mass transport and diffusion gradients within the cell aggregates and the whole scaffold. Moreover, the influence of aggregate size on cell differentiation could be recently demonstrated for human embryonic stem cells[44]. Therefore, chips with defined geometries for cellular aggregation may be helpful tools in stem cell research. Another important advantage of the chip is the defined surface area, which permits the application of known cell densities in the chip cavities and defined surface modifications like coating with extracellular matrix components, leading to distinct culture conditions and reproducible experiments. In this context, simple coating of the chip surface with extracted extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen, represents a rather simple surface modification, whereas more sophisticated modification techniques have been developed in our laboratory, for example, the integration of defined nanotopographies on the inner surface of the curved microcavity walls[45].

Figure 2.

Primary human hepatocytes and Hep G2 hepatoma cells 5 d and 24 h after cell seeding into r- (A) and cf-KITChips (B) respectively (upper panels: top view, lower panels: cross section). The r-KITChip (20 mm × 20 mm in total) is comprised of up to 625 round microcontainers (diameter up to 300 μm, depth up to 300 μm) or 1156 cubic microcontainers (300 μm × 300 μm × 300 μm in w × l × h) for the cf-KITChip of which 5 × 5 can be seen in 2A and 4 × 4 can be seen in 2B. Live cell staining with Syto 16. Scale bar: 250 μm.

MICRO-BIOREACTORS FOR 3D-CULTURE

As a result of cellular metabolic activity, 3D high density cell culture can lead to limited nutrient and oxygen supply as well as accumulation of toxic metabolites in the tissue construct. Furthermore, it has been shown that fluid flow or shear stress can influence cell behavior like osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells[46-49]. Micro-bioreactors specifically designed for 3D cell culture provide an opportunity to overcome these mass transfer limitations in high density cell cultures and offers the possibility of studying the influence of mechanical forces like fluid flow or hydrodynamic pressure on cell responses. For this purpose numerous bioreactor designs have been developed, which can be divided in stirred flasks like spinner-flask or rotating-wall vessel (RWV) bioreactors, fluidized or fixed bed bioreactors, hollow-fiber bioreactors and systems using perfused scaffolds. All these systems to some extent use a combination of common 3D cell culture techniques like gel-based techniques, spheroids, encapsulated or immobilized cells on various types of 3D-matrices. However, many bioreactor systems must cope with difficulties like large death volumes, heterogeneous cell distribution in the scaffold or bioreactor, large diffusion distances and non-uniform perfusion of the scaffolds due to different flow resistances inside the matrices[50]. For instance, in hollow-fiber bioreactors cells may be embedded in gels to improve cell distribution and are cultured inside or outside of semi-permeable hollow fibers, while culture medium flows on the reverse side, respectively. In these systems mass transport takes place by diffusion and it has to be considered that fiber diameter and length play an important role since radial and longitudinal gradients may be formed.

Systems using encapsulated cells like fluidized or fixed bed bioreactors show similar mass transfer limitations due to slow diffusion across the capsules[50]. Bioreactors based on perfused scaffolds show a better nutrient supply compared to the above mentioned systems since cells immobilized on 3D-matrices are in direct contact with the culture medium. However, not all of the systems, termed “perfusion systems”, use a setup where scaffolds are directly perfused with culture medium. More precisely, one should differentiate between perfused culture chambers where culture medium flows around the scaffold[51,52], and perfusion through the scaffold and the tissue inside[46,53,54]. For better differentiation between the two different setups, we have coined the term superfusion for the flow around the scaffold. The KITChip-culture system is comprised of a chip and a bioreactor that allows the use of both superfusion and perfusion and even a combination of the two. Moreover, sensors for oxygen and other determinations can easily be integrated.

CONCLUSION

Since the early days of 3D-culture a vast number of investigations have been performed to identify the factors relevant for cell survival, proliferation and/or differentiation in vitro. Based on progress in the research fields of biology, material science and engineering, a multitude of different culture techniques, sophisticated cell culture scaffolds and micro-bioreactors have been developed that are nearly as diverse as the tissues of the body.

Based on the advances in surface modification and micro- and nano-structuring techniques, new applications and, therefore most likely, new concepts for 3D-tissue cultures will arise. Today, scientists already provide a tool box for the design of appropriate 3D-culture configurations depending on the cell type and experimental setup, thus moving closer to in vivo conditions. This is of particular importance with regard to control stem cell maintenance, expansion and differentiation, as well as the generation of artificial tissue for applications in medicine or high-throughput screening systems in the pharmaceutical and chemical industry.

However, if 3D cell culture techniques better reflect the natural microenvironment of tissues and current advanced technologies allow the design and fabrication of numerous 3D-culture systems, why then is the Petri dish, or rather the monolayer culture, still the standard technique in most cell culture labs? The reasons are simple and convincing: monolayer culture devices are easy to manufacture and thus they are inexpensive to produce, which in turn allows mass production. Many companies have a large portfolio of related products and, last but not least, they are easy to handle. Especially the latter and the fact that many 3D-culture systems are of academic nature and not commercially available are the major obstacles that prevent faster distribution of organotypic culture systems and their becoming new standards. For instance, commercially available 3D-culture systems comprise mainly sponges (e.g. collagen or calcium-phosphate sponges), hydrogels made of natural polymers like alginate or extracellular matrix components or more rare synthetic peptide hydrogels and cell culture flasks coated with nanofibers representing a synthetic substrate for cells in monolayer culture. All these systems are designed for stationary culture in multiwell cell culture plates, while available fluidic 3D-culture systems using bioreactors are based on encapsulated cells or cells immobilized on microcarriers in rotating bed/wall vessel bioreactors displaying in part the already discussed limitations. Furthermore, many standardized techniques for cell analysis used so far in conventional monolayer culture, like cell lysis for mRNA or protein extraction, immunostaining or quantification of secreted proteins into the culture medium, are often difficult to transfer to 3D-culture systems, especially in gel-based systems as gels often hinder the accessibility of the cells. However, as more and more academic systems become commercially available, the increasing number of standard protocols adapted to 3D-cultures will help to improve their acceptance and diffusion.

Footnotes

Supported by The European Union Grant STREP NMP3-CT-29005-013811 (to Welle A); the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Grant 03ZIK-465 (to Altmann B), Germany

Peer reviewer: Umberto Galderisi, PhD, Associate Professor of Molecular Biology, Department of Experimental Medicine, Second University of Naples, Via L. De Crecchio 7, 80138 Napoli, Italy

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Petri RJ. Eine kleine Modification des Koch´schen Plattenverfahrens. Centralbl Bacteriol Parasitenkunde. 1887;1:279–280. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtfreter J. A study of the mechanics of gastrulation: Part II. J Exp Zool. 1944;95:171–212. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moscona A. Cell suspensions from organ rudiments of chick embryos. Exp Cell Res. 1952;3:535–539. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moscona A. The development in vitro of chimeric aggregates of dissociated embryonic chick and mouse cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1957;43:184–194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.43.1.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moscona A. Rotation-mediated histogenetic aggregation of dissociated cells. A quantifiable approach to cell interactions in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1961;22:455–475. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland RM, Durand RE. Radiation response of multicell spheroids--an in vitro tumour model. Curr Top Radiat Res Q. 1976;11:87–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koide N, Shinji T, Tanabe T, Asano K, Kawaguchi M, Sakaguchi K, Koide Y, Mori M, Tsuji T. Continued high albumin production by multicellular spheroids of adult rat hepatocytes formed in the presence of liver-derived proteoglycans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:385–391. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu FJ, Friend JR, Remmel RP, Cerra FB, Hu WS. Enhanced cytochrome P450 IA1 activity of self-assembled rat hepatocyte spheroids. Cell Transplant. 1999;8:233–246. doi: 10.1177/096368979900800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Absi SF, Friend JR, Hansen LK, Hu WS. Structural polarity and functional bile canaliculi in rat hepatocyte spheroids. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:56–67. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akins RE, Boyce RA, Madonna ML, Schroedl NA, Gonda SR, McLaughlin TA, Hartzell CR. Cardiac organogenesis in vitro: reestablishment of three-dimensional tissue architecture by dissociated neonatal rat ventricular cells. Tissue Eng. 1999;5:103–118. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decker ML, Behnke-Barclay M, Cook MG, La Pres JJ, Clark WA, Decker RS. Cell shape and organization of the contractile apparatus in cultured adult cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23:817–832. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonaventure J, Kadhom N, Cohen-Solal L, Ng KH, Bourguignon J, Lasselin C, Freisinger P. Reexpression of cartilage-specific genes by dedifferentiated human articular chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:97–104. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo JF, Jourdian GW, MacCallum DK. Culture and growth characteristics of chondrocytes encapsulated in alginate beads. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;19:277–297. doi: 10.3109/03008208909043901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montesano R, Mouron P, Amherdt M, Orci L. Collagen matrix promotes reorganization of pancreatic endocrine cell monolayers into islet-like organoids. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:935–939. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrera D, Poggi S, Biassoni C, Dickson GR, Astigiano S, Barbieri O, Favre A, Franzi AT, Strangio A, Federici A, et al. Three-dimensional cultures of normal human osteoblasts: proliferation and differentiation potential in vitro and upon ectopic implantation in nude mice. Bone. 2002;30:718–725. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00691-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granet C, Laroche N, Vico L, Alexandre C, Lafage-Proust MH. Rotating-wall vessels, promising bioreactors for osteoblastic cell culture: comparison with other 3D conditions. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1998;36:513–519. doi: 10.1007/BF02523224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagley J, Rosenzweig M, Marks DF, Pykett MJ. Extended culture of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors without cytokine augmentation in a novel three-dimensional device. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:496–504. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(98)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doetschman TC, Eistetter H, Katz M, Schmidt W, Kemler R. The in vitro development of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cell lines: formation of visceral yolk sac, blood islands and myocardium. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;87:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:265–272. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grayson WL, Ma T, Bunnell B. Human mesenchymal stem cells tissue development in 3D PET matrices. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:905–912. doi: 10.1021/bp034296z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Kim UJ, Blasioli DJ, Kim HJ, Kaplan DL. In vitro cartilage tissue engineering with 3D porous aqueous-derived silk scaffolds and mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7082–7094. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBurney MW, Jones-Villeneuve EM, Edwards MK, Anderson PJ. Control of muscle and neuronal differentiation in a cultured embryonal carcinoma cell line. Nature. 1982;299:165–167. doi: 10.1038/299165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Engineering substrate topography at the micro- and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5406–5415. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz MA, DeSimone DW. Cell adhesion receptors in mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen JA, Swartz MA. Mechanobiology in the third dimension. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:1469–1490. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada KM, Pankov R, Cukierman E. Dimensions and dynamics in integrin function. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:959–966. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Cell interactions with three-dimensional matrices. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, Cuddihy MJ, Kotov NA. Three-dimensional cell culture matrices: state of the art. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:61–86. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:655–663. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunn JC, Yarmush ML, Koebe HG, Tompkins RG. Hepatocyte function and extracellular matrix geometry: long-term culture in a sandwich configuration. FASEB J. 1989;3:174–177. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.2.2914628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for tissue engineering applications: a review. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1197–1211. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moroni L, de Wijn JR, van Blitterswijk CA. Integrating novel technologies to fabricate smart scaffolds. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008;19:543–572. doi: 10.1163/156856208784089571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welle A, Kröger M, Döring M, Niederer K, Pindel E, Chronakis IS. Electrospun aliphatic polycarbonates as tailored tissue scaffold materials. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2211–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuzlakoglu K, Bolgen N, Salgado AJ, Gomes ME, Piskin E, Reis RL. Nano- and micro-fiber combined scaffolds: a new architecture for bone tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:1099–1104. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-4713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knedlitschek G, Schneider F, Gottwald E, Schaller T, Eschbach E, Weibezahn KF. A tissue-like culture system using microstructures: influence of extracellular matrix material on cell adhesion and aggregation. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:35–39. doi: 10.1115/1.2798040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giselbrecht S, Gietzelt T, Gottwald E, Guber AE, Trautmann C, Truckenmüller R, Weibezahn KF. Microthermoforming as a novel technique for manufacturing scaffolds in tissue engineering (CellChips) IEE Proc Nanobiotechnol. 2004;151:151–157. doi: 10.1049/ip-nbt:20040824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottwald E, Giselbrecht S, Augspurger C, Lahni B, Dambrowsky N, Truckenmüller R, Piotter V, Gietzelt T, Wendt O, Pfleging W, et al. A chip-based platform for the in vitro generation of tissues in three-dimensional organization. Lab Chip. 2007;7:777–785. doi: 10.1039/b618488j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weibezahn KF, Knedlitschek G, Dertinger H, Schubert K, Bier W, Schaller T. Cell culture substrate. International Patent; 1993. p. WO 93/07258. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giselbrecht S, Gietzelt T, Gottwald E, Trautmann C, Truckenmüller R, Weibezahn KF, Welle A. 3D tissue culture substrates produced by microthermoforming of pre-processed polymer films. Biomed Microdevices. 2006;8:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s10544-006-8174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Truckenmüller R, Giselbrecht S, van Blitterswijk C, Dambrowsky N, Gottwald E, Mappes T, Rolletschek A, Saile V, Trautmann C, Weibezahn KF, et al. Flexible fluidic microchips based on thermoformed and locally modified thin polymer films. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1570–1579. doi: 10.1039/b803619e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peerani R, Rao BM, Bauwens C, Yin T, Wood GA, Nagy A, Kumacheva E, Zandstra PW. Niche-mediated control of human embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. EMBO J. 2007;26:4744–4755. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giselbrecht S, Reinhardt M, Schleunitz A, Gottwald E, Truckenmueller R. Microstructured cell culture chips with integrated nanotopography. In: 5th International Conference on Microtechnologies in Medicine and Biology., editor. Canada: Quebec City; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bancroft GN, Sikavitsas VI, van den Dolder J, Sheffield TL, Ambrose CG, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. Fluid flow increases mineralized matrix deposition in 3D perfusion culture of marrow stromal osteoblasts in a dose-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12600–12605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202296599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao F, Chella R, Ma T. Effects of shear stress on 3-D human mesenchymal stem cell construct development in a perfusion bioreactor system: Experiments and hydrodynamic modeling. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96:584–595. doi: 10.1002/bit.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao F, Grayson WL, Ma T, Irsigler A. Perfusion affects the tissue developmental patterns of human mesenchymal stem cells in 3D scaffolds. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:421–429. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim DH, Kim SH, Heo SJ, Shin JW, Lee SW, Park SA, Shin JW. Enhanced differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into NP-like cells via 3D co-culturing with mechanical stimulation. J Biosci Bioeng. 2009;108:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allen JW, Hassanein T, Bhatia SN. Advances in bioartificial liver devices. Hepatology. 2001;34:447–455. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao F, Ma T. Perfusion bioreactor system for human mesenchymal stem cell tissue engineering: dynamic cell seeding and construct development. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91:482–493. doi: 10.1002/bit.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toh YC, Lim TC, Tai D, Xiao G, van Noort D, Yu H. A microfluidic 3D hepatocyte chip for drug toxicity testing. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2026–2035. doi: 10.1039/b900912d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timmins NE, Scherberich A, Früh JA, Heberer M, Martin I, Jakob M. Three-dimensional cell culture and tissue engineering in a T-CUP (tissue culture under perfusion) Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2021–2028. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vukasinovic J, Cullen DK, LaPlaca MC, Glezer A. A microperfused incubator for tissue mimetic 3D cultures. Biomed Microdevices. 2009;11:1155–1165. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]