Abstract

The use of cellular telephones has grown explosively during the past two decades, and there are now more than 279 million wireless subscribers in the United States. If cellular phone use causes brain cancer, as some suggest, the potential public health implications could be considerable. One might expect the effects of such a prevalent exposure to be reflected in general population incidence rates, unless the induction period is very long or confined to very long-term users. To address this issue, we examined temporal trends in brain cancer incidence rates in the United States, using data collected by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Log-linear models were used to estimate the annual percent change in rates among whites. With the exception of the 20–29-year age group, the trends for 1992–2006 were downward or flat. Among those aged 20–29 years, there was a statistically significant increasing trend between 1992 and 2006 among females but not among males. The recent trend in 20–29-year-old women was driven by a rising incidence of frontal lobe cancers. No increases were apparent for temporal or parietal lobe cancers, or cancers of the cerebellum, which involve the parts of the brain that would be more highly exposed to radiofrequency radiation from cellular phones. Frontal lobe cancer rates also rose among 20–29-year-old males, but the increase began earlier than among females and before cell phone use was highly prevalent. Overall, these incidence data do not provide support to the view that cellular phone use causes brain cancer.

Keywords: brain cancer, cellular telephones, epidemiology, SEER

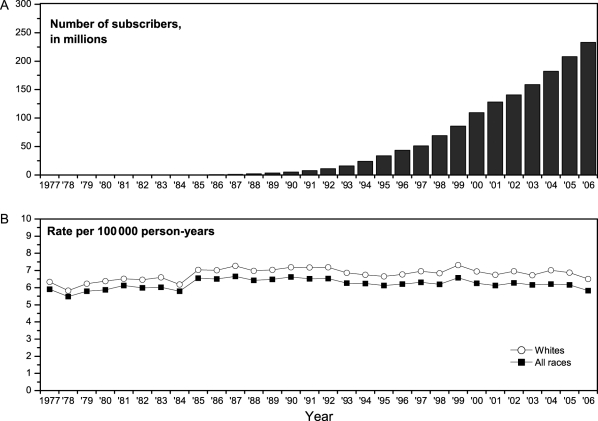

Recent temporal trends in the age-specific incidence of brain cancer are of interest in light of concerns about possible effects of novel environmental exposures, in particular radiofrequency (RF) radiation from cellular telephones.1 Although first used in the 1980s, cellular telephones did not come into widespread use in the United States until the mid- to late 1990s. Their use is now pervasive, with more than 279 million wireless subscribers in the United States as of December 2008 (Fig. 1A).2 There have been reports in the literature that the incidence of brain cancer has increased in recent years;3,4 however, data from national cancer registries in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden showed stable rates from the mid-1980s through 2003,5,6 and data collected by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program indicated declining or stable age-adjusted brain cancer incidence rates between 1992 and 2006.7 Here, we consider the question in greater detail, including trends by age group and location of cancer in the brain.

Fig. 1.

(A) Number of wireless subscribers in the United States, 1984–2006;2 (B) age-adjusted incidence of brain cancer (2000 population standard), SEER 9, 1984–2006.

Methods

The study was conducted using data collected by the SEER Program and included white patients diagnosed with brain cancer [ICD-O8 topography codes C71.0–C71.9, excluding meningiomas and lymphomas/leukemias: morphology codes 9530–9539 and 9590–9989] during 1977–2006 and reported to 1 of 9 statewide or regional population-based cancer registries (2009 submission). The original 9 registries included the states of Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, and Utah, plus the metropolitan areas of Atlanta (Georgia), Detroit (Michigan), San Francisco (California), and Seattle (Washington), and cover approximately 10% of the US population. Age-specific and age-adjusted incidence rates, directly standardized to the 2000 US population, were calculated and expressed per 100 000 person-years, separately for males and females. SEER*Stat version 6.5.29 was used to fit log-linear models, estimate the annual percent change in incidence rates, and calculate 95% confidence intervals according to the method of Tiwari et al.10 All statistical tests were two-sided at the α = 0.05 level. Trends were estimated separately for 1977–1991 and 1992–2006. The earlier interval includes the years when computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologies were introduced and growing in use but precedes the widespread use of cellular telephones. Only trends for the latter interval are relevant to the cellular phone issue; however, the longer term pattern provides the context in which to interpret the more recent data. By the 1990s, CT and MRI machines had become widely available in the medical care system, making temporal variation in diagnosis less of an issue.

Results

A total of 38 788 brain cancers were diagnosed among whites over the 30-year period, of which more than 95% were gliomas.

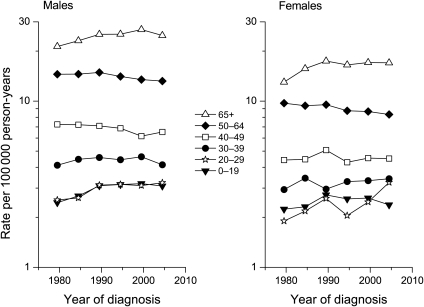

The overall incidence of brain cancer changed little during the period when the use of cellular phones increased sharply (Fig. 1B). Age- and sex-specific trends in the incidence of brain cancers are shown in Fig. 2, and annual percentage changes are summarized in Table 1. For those under 30 years and those 65 years or older, there were highly significant increasing trends in incidence from 1977 to 1991. With the exception of the 20–29-year age group, the trends for 1992–2006 were downward or flat, with the downward trend for 50–64-year olds approaching statistical significance. Among women aged 20–29 years, there was a statistically significant increasing trend between 1992 and 2006; no such trend was seen for males.

Fig. 2.

Brain cancer incidence trends among whites by age, SEER 9, 1977–1981 to 2002–2006.

Table 1.

Age-specific trends in brain cancer incidencea among whites in the United States during 1977–1991 and 1992–2006, SEER 9

| Age at diagnosis (years) | Calendar year of diagnosis | Annual percentage change (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males + females | Males | Females | ||

| <20 | 1977–1991 | 1.93* (0.57, 3.31) | 2.48* (1.26, 3.70) | 1.28 (−0.96, 3.57) |

| 1992–2006 | −0.42 (−1.84, 1.02) | −0.13 (−1.70, 1.46) | −0.75 (−2.38, 0.90) | |

| 20–29 | 1977–1991 | 2.52* (1.31, 3.76) | 2.08* (0.24, 3.97) | 2.94* (1.17, 4.73) |

| 1992–2006 | 1.78* (0.48, 3.10) | −0.12 (−1.67, 1.45) | 4.27* (1.88, 6.71) | |

| 30–39 | 1977–1991 | 0.71 (−0.85, 2.29) | 1.06 (−0.21, 2.34) | 0.02 (−2.52, 2.62) |

| 1992–2006 | −0.57 (−1.68, 0.55) | −0.99 (−2.48, 0.53) | −0.02 (−1.67, 1.65) | |

| 40–49 | 1977–1991 | 0.35 (−0.99, 1.71) | −0.20 (−1.64, 1.26) | 1.19 (−0.65, 3.07) |

| 1992–2006 | −0.34 (−1.16, 0.49) | −0.76 (−1.99, 0.48) | 0.29 (−1.17, 1.78) | |

| 50–64 | 1977–1991 | 0.18 (−0.64, 1.00) | 0.33 (−0.72, 1.40) | −0.09 (−1.66, 1.50) |

| 1992–2006 | −0.48 (−1.00, 0.04) | −0.36 (−1.12, 0.40) | −0.74 (−1.54, 0.06) | |

| 65+ | 1977–1991 | 2.23* (1.61, 2.86) | 1.63* (0.71, 2.57) | 2.90* (1.99, 3.81) |

| 1992–2006 | 0.02 (−0.68, 0.72) | −0.34 (−1.16, 0.48) | 0.15 (−0.78, 1.09) | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

aBased on age-standardized rates to the 2000 US population.

*P < 0.05.

To explore this increasing trend among females in greater detail, we examined a temporal pattern by tumor location within the brain and tumor histology. The recent increasing trend in 20–29-year-old women was due to rising incidence of frontal lobe tumors (Table 2). No trend was apparent for temporal or parietal lobe tumors, nor for tumors of poorly specified location. There was an increasing trend for frontal lobe cancers in males that began earlier than in females. The male:female incidence rate ratio was >1.00 for all time periods except for 2002–2006, when it dropped abruptly to 0.99 (Table 2). The trend for glioblastoma multiforme, the most common type of brain cancer in adults, was similar to that for all types of brain cancer combined (data not shown).

Table 2.

Brain cancer incidence rates among whites, ages 20–29 years, by gender, location of cancer within the brain, and calendar year of diagnosis, 1977–1981 to 2002–2006, SEER 9

| Site of cancer | Year of diagnosis (Incidence rate, per 100 000 person-years [count]) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977–1981 | 1982–1986 | 1987–1991 | 1992–1996 | 1997–2001 | 2002–2006 | |

| Females | ||||||

| Frontal lobe | 0.56 (45) | 0.54 (45) | 0.59 (45) | 0.63 (45) | 0.79 (54) | 1.15 (76) |

| Temporal lobe | 0.20 (16) | 0.35 (29) | 0.37 (28) | 0.39 (27) | 0.47 (32) | 0.38 (25) |

| Parietal lobe | 0.20 (16) | 0.16 (13) | 0.29 (21) | 0.20 (14) | 0.19 (13) | 0.23 (15) |

| Cerebellum | 0.21 (17) | 0.28 (23) | 0.25 (19) | 0.19 (13) | 0.26 (17) | 0.32 (21) |

| Other specifieda | 0.36 (29) | 0.47 (38) | 0.61 (46) | 0.30 (21) | 0.39 (26) | 0.64 (42) |

| Poorly specifiedb | 0.36 (29) | 0.37 (31) | 0.50 (38) | 0.35 (24) | 0.37 (24) | 0.53 (35) |

| Total | 1.90 (152) | 2.18 (179) | 2.60 (197) | 2.05 (144) | 2.47 (166) | 3.25 (214) |

| Males | ||||||

| Frontal lobe | 0.49 (40) | 0.78 (66) | 0.81 (64) | 0.89 (64) | 0.95 (68) | 1.20 (86) |

| Temporal lobe | 0.39 (32) | 0.31 (26) | 0.60 (48) | 0.41 (30) | 0.41 (29) | 0.59 (42) |

| Parietal lobe | 0.20 (16) | 0.27 (22) | 0.25 (19) | 0.34 (24) | 0.28 (20) | 0.22 (16) |

| Cerebellum | 0.38 (31) | 0.25 (21) | 0.44 (34) | 0.47 (32) | 0.32 (22) | 0.26 (19) |

| Other specifieda | 0.53 (43) | 0.53 (44) | 0.61 (48) | 0.45 (32) | 0.49 (34) | 0.51 (37) |

| Poorly specifiedb | 0.55 (45) | 0.48 (40) | 0.42 (34) | 0.60 (44) | 0.66 (47) | 0.44 (32) |

| Total | 2.55 (207) | 2.62 (219) | 3.12 (247) | 3.16 (226) | 3.11 (220) | 3.23 (232) |

| Male:female ratioc | 1.34 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.54 | 1.26 | 0.99 |

aOther specified = occipital lobe + cerebrum (lobe not specified) + ventricle, not otherwise specified + brain stem.

bPoorly specified = overlapping lesions + brain, not otherwise specified.

cBased on total incidence rates for 20–29-year olds.

Discussion

Overall, brain cancer incidence rates have declined since the early 1990s. The rising rates in earlier years in persons younger than 30 or older than 64 did not come as a surprise, as these patterns have been well documented in previous analyses of SEER data.11,12 By far the largest part of this apparent increase in incidence is believed to be attributable to improved diagnosis, related in large part to the introduction of CT scans in the 1970s followed by MRI scans in the 1980s. Other factors, such as improved access to care and an increase in the number of specialists, may also have played a role. In any case, cellular telephones could not have been an important causal factor for cancers diagnosed before the 1990s, and incidence rates have been flat or decreasing since that time.

Susceptibility to the one known human neurocarcinogen, ionizing radiation, is greatest among young children,13,14 perhaps because of greater sensitivity of the developing brain. In addition, some data suggest that energy deposition from RF radiation from cellular phones is greater and penetrates more deeply in the brains of children than adults because of differences in skull characteristics.15,16 Therefore, it has been proposed that an effect of cellular phone use should be most apparent in those who began use as children and have now aged into early adulthood.

In the present study, the only subgroup showing a significant increasing trend since 1992 was 20–29-year-old females. On first consideration, the rising incidence in young women might be interpreted as evidence supportive of the idea that cell phones pose a cancer risk. However, more thorough examination of the data reveals patterns that are inconsistent with a causal interpretation. The temporal lobe is the part of the brain most heavily exposed to RF radiation from cellular telephones;17 yet, no rise in incidence was apparent for temporal lobe tumors. Rather, the overall trend was due to an increase in frontal lobe tumors. Depending on the type of cellular phone and the manner in which it is used, the specific absorption rate of RF radiation is at least several times higher in the temporal lobe than in the frontal lobe.17 An increase in frontal lobe tumors also was seen among 20–29-year-old males, but its onset preceded that in females and occurred before cell phone use was highly prevalent; the trend for all brain cancers combined in 20–29-year-old males between 1992 and 2006 was negative, though not significantly so. It is implausible that cell phone use poses a cancer risk in women but not in men. The increase among women beginning in the 1992–1996 interval followed a drop during 1987–1991 (Fig. 2); both could be due to random variation. Lastly, the age at exposure dependence for the neurocarcinogenic effects of ionizing radiation is largely due to the sensitivity of the very young (<5 years);14 very young children are not frequent users of cellular phones. This, plus the fact that the energy of ionizing radiation is of greater magnitude than that of RF radiation, indicates that ionizing radiation does not qualify as a good model for sensitivity of teenagers to nonionizing radiation.

Left unexplained are the general downward trend in brain cancer incidence since the early 1990s, the apparent increase in the incidence of frontal lobe cancers (predominantly gliomas), and a recent change in the sex ratio of brain cancer in young adults. Part of the decrease in incidence may be due to population admixture related to the increasing Hispanic population. Hispanic whites have a lower incidence of brain cancer than non-Hispanic whites.7 SEER 9 historically did not distinguish the two, but Hispanic ethnicity has been collected since 1992. To assess the possible importance of this factor, we compared rates for all whites in SEER 9 with those for white non-Hispanics during 1992–2006; the effect of failing to account for Hispanic ethnicity was relatively small, on the order of 1–3% of incidence rates. In analyses based exclusively on SEER 13, no trend in brain cancer incidence was seen for any racial/ethnic group from 1992 to 2006. Although it is likely that the use of MRIs in the 1980s advanced the date of diagnosis of some brain cancers, the types of cancers that tend to occur in older people tend to be highly aggressive and rapidly growing. It is difficult to see how such an effect could be on the order of 10 years or more, such that it would deplete the pool of cancers that otherwise would be diagnosed between 1992 and 2006. There have been improvements in the diagnosis and reporting of brain cancers over time, as well as changes in the classification of brain cancers.18–20 One effect of more accurate and precise diagnosis would be shifting of cases from vaguely specified categories into more specific types, both as to histology and location, but it is not apparent why this would be differential for frontal lobe cancers.

There are several limitations to this study. Most importantly, if risk is only increased among long-term users and/or after a long induction period, it may be too soon for an effect to be apparent in general population incidence rates. However, even for a long mean induction time, one would expect a distribution around this mean, and sufficient time has elapsed since the use of cellular telephones began that one would expect to see cases with shorter than average induction periods.1,21 It is logically inconsistent to interpret positive findings from selected published epidemiological studies of cellular telephones, including that of relatively short-term users, as being indicative of causality while simultaneously asserting that it is still too soon to see an increase at the population level. A second issue is that incidence data for the most recent calendar years likely will be revised upward, as additional cancers are identified and registered in SEER; however, delay-adjusted brain cancer incidence rates among whites were very similar to observed rates for years prior to 2006.7 Third, population-level analysis is not well suited to detecting small effects. Lastly, we could not assess trends in the incidence of benign intracranial tumors, such as meningioma and acoustic neuroma, because SEER only recently began to systematically collect incidence data for these tumors. Some US registries have collected such data for a longer time,22 but there is some question about whether completeness of reporting of benign tumors has been stable over time among the different registries. Specifically, it is possible that ascertainment of benign tumors has increased.

Overall, these incidence data from the United States based on high-quality cancer registries do not provide support for the view that use of cellular phones causes brain cancer.

Funding

This research was supported by intramural funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathan Appel of Information Management Systems and David Check for programming support. We also acknowledge the work of the SEER program in collecting the data that made our study possible.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Ahlbom A, Feychting M, Green A, Kheifets L, Savitz DA, Swerdlow AJ and ICNIRP (International Commission for Non-ionizing Radiation Protection) Standing committee on Epidemiology. Epidemiologic evidence on mobile phones and tumor risk: a review. Epidemiology. 2009;20:639–652. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181b0927d. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181b0927d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CTIA (Cellular Telephone Industry Association) CTIA: The Wireless Association. www.ctia.org . Accessed September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardell L, Carlberg M. Mobile phones, cordless phones, and the risk for brain tumours. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:5–17. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khurana VG, Teo C, Kundi M, Hardell L, Carlberg M. Cell phones and brain tumors: a review including the long-term epidemiological data. Surg Neurol. 2009;72:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2009.01.019. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lönn S, Klaeboe L, Hall P, Mathiesen T, Auvinen A, Christensen HC, et al. Incidence trends of adult primary intracerebral tumors in four Nordic countries. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:450–455. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11578. doi:10.1002/ijc.11578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deltour I, Johansen C, Auvinen A, Feychting M, Klaeboe L, Schuz J. Time trends in brain tumor incidence rates in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, 1974–2003. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1721–1724. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/ , based on 2008 SEER data submission posted to the SEER web site, 2009. Accessed January 21, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ICDO (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology). 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.SEER (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results) National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat. ) version 6.5.2http://seer.gov/seerstat . Accessed November 4, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15:547–569. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. doi:10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MA, Friedlin B, Ries LAG, Simon Trends in reported incidence of primary malignant brain tumors in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1269–1277. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.17.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legler JM, Ries LAG, Smith MA, et al. Brain and other central nervous system cancers: recent trends in incidence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1382–1390. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadetzki S, Chetrit A, Freedman L, Stovall M, Modan B, Novikov I. Long-term follow-up for brain tumor development after childhood exposure to ionizing radiation for Tinea capitis. Radiat Res. 2005;163:424–432. doi: 10.1667/rr3329. doi:10.1667/RR3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neglia JP, Robison LL, Liu Y, et al. New primary neoplasms of the central nervous system in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1528–1537. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi OP, Lazzi G, Furse CM. Electromagnetic absorption in the human head and neck for cell telephones at 835 and 1900 MHz. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech. 1996;44(10):1884–1897. doi:10.1109/22.539947. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi OP, Kang G. Some present problems and a proposed experimental phantom for SAR compliance testing of cellular telephones at 835 and 1900 MHz. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47:1501–1518. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/9/306. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/47/9/306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardis E, Deltour I, Mann S, et al. Distribution of RF energy emitted by mobile phones in anatomical structures of the brain. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:2771–2783. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/11/001. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/53/11/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. The new WHO classification of brain tumors. Brain Pathol. 1993;3:255–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1993.tb00752.x. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1993.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman S, Propp J, McCarthy BJ. Temporal trends in incidence of primary brain tumors in the United States, 1985–1999. Neuro-Oncology. 2006;8:27–37. doi: 10.1215/S1522851705000323. doi:10.1215/S1522851705000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy BJ, Propp J, Davis FG, Burger PC. Time trends in oligodendroglial and astrocytic tumor incidence. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:34–44. doi: 10.1159/000115440. doi:10.1159/000115440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman KJ. Health effects of mobile telephones. Epidemiology. 2009;20:653–655. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181aff1f7. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181aff1f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CBTRUS (Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States) Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 2000–2004. Hinsdale, IL: Published by the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States; 2008. [Google Scholar]