Abstract

Atherogenic dyslipidemia, including low HDL levels, is the major contributor of residual risk of cardiovascular disease that remains even after aggressive statin therapy to reduce LDL-cholesterol. Currently, distinction is not made between HDL-cholesterol and HDL, which is a lipoprotein consisting of several proteins and a core containing cholesteryl esters (CEs). The importance of assessing HDL functionality, specifically its role in facilitating cholesterol efflux from foam cells, is relevant to atherogenesis. Since HDLs can only remove unesterified cholesterol from macrophages while cholesterol is stored as CEs within foam cells, intracellular CE hydrolysis by CE hydrolase is vital. Reduction in macrophage lipid burden not only attenuates atherosclerosis but also reduces inflammation and linked pathologies such as Type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Targeting reduction in macrophage CE levels and focusing on enhancing cholesterol flux from peripheral tissues to liver for final elimination is proposed.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, cholesterol homeostasis, cholesteryl ester hydrolase, HDL, inflammation, macrophage

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the USA [1]. Risk for the development of atherosclerosis is widespread and generally underestimated in asymptomatic adults. Greenland et al. reported that approximately 37% of US adults have two or more risk factors for CVD and 90% of patients with coronary heart disease have at least one atherosclerotic risk factor [2]. More importantly, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed that approximately 50% of all coronary deaths are not preceded by cardiac symptoms or diagnosis [3]. These statistics underscore the importance of developing novel approaches for risk assessment and evaluation, not only in patients with CVD but also in asymptomatic adults.

The relationship between LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) and risk for CVD is well established and measurement of LDL-C is routinely used for two distinct clinical applications: risk assessment, with high LDL-C associated with elevated risk for CVD, and risk management, with low LDL-C levels serving as treatment goals and indicators of the success of lipid-lowering therapies [4]. Although routinely referred to as plasma LDL levels, what is truly measured is the amount of cholesterol associated with LDL particle or LDL-C, and it is important to make this distinction. It is the amount of cholesterol associated with LDL particles or LDL-C that associates with elevated risk for CVD, and a direct relationship between LDL particle number and increased risk is yet to be completely defined.

Over the last four decades, significant progress has been made towards the prevention of CVD, primarily by targeted reduction in LDL-C. However, with the increasing epidemic of obesity, metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), this progress is now being challenged. Although use of statins is central to the management of dyslipidemia and largely accounts for the significant reduction in mortality associated with CVD, extensive evidence from large, prospective clinical trials suggests that a significant CVD risk still persists despite effective LDL-C-lowering treatment. A recent meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials of statins evaluated the efficacy of cholesterol-lowering treatment and concluded that one in seven treated patients experienced events over 5 years, indicative of residual risk despite achievement of target LDL-C levels [5].

The Treating to New Targets (TNT) study examined the clinical benefits of reducing the LDL-C levels to well below 100 mg/dl in patients with stable coronary heart disease and slightly elevated LDL-C levels. Although a 22% reduction in cardiovascular event rate was noted in aggressively treated subjects (80 mg atorvastatin) compared with those receiving the 10-mg dose, there was still a residual risk of 8.7% [6]. The Residual Risk Initiative (R3I) was established to address this important issue and it has now identified the role of atherogenic dyslipidemia as a major contributor to the observed residual risk [7]. In addition to elevated triglycerides (TGs), atherogenic dyslipidemia is characterized by a low plasma concentration of HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) prevalent in patients with T2DM, metabolic syndrome and/or established CVD. As with LDL and LDL-C, it is important to make the distinction between HDL and HDL-C. Although it is the amount of cholesterol associated with HDL particles that is routine measured, it is inappropriately referred to as HDL, which is truly a lipoprotein particle. The correct description should be HDL-C and will be used throughout this article.

High-denisty lipoprotein-cholesterol is a strong a predictor of the risk of CVD as LDL-C or TGs [8], and incidence of cardiovascular death or non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) is significantly and inversely correlated with HDL-C concentration [9]. It needs to be emphasized that HDL is a lipoprotein composed of the predominant structural protein apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), several other minor proteins and a core of lipids consisting primarily of cholesteryl esters. Routinely determined HDL-C concentration is simply the amount of total cholesterol associated with the HDL particle and does neither describe HDL composition nor its functionality. Several mechanisms have been identified by which HDL protects against CVD, including facilitation of reverse cholesterol transport, modulation of endothelial function, and antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic and anti-apoptotic effects [10,11]. Recent characterization of HDL proteome has identified several clusters of related proteins that collectively or individually contribute to the earlier mentioned atheroprotective properties of HDL [12]. However, the role of HDL in removing cholesterol from peripheral tissues, including the artery wall or atherosclerotic plaque-associated macrophage foam cells, and transporting it to the liver for secretion in the bile and ultimate elimination from the body by the process of reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), will be the only HDL function discussed in this article.

HDL & RCT

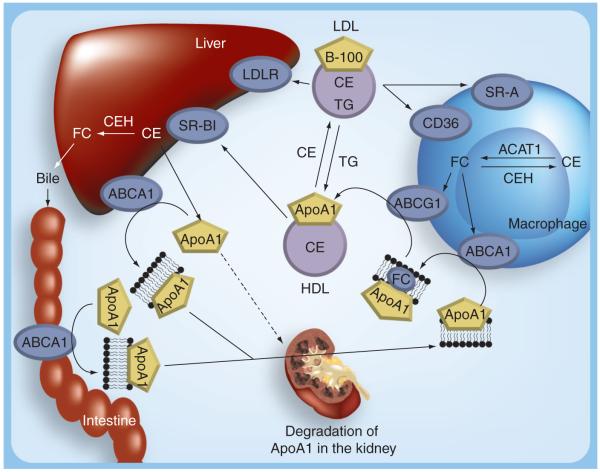

The effect of HDL on RCT is likely the most important mechanism by which HDL reduces CVD risk. Figure 1 summarizes the steps involved in HDL metabolism. The primary structural protein of HDL, ApoA1, is synthesized and secreted predominantly by the liver and to a lesser extent by the intestine. It is rapidly lipidated with phospholipids transported via ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter A1 (ABCA1). This initial lipidation is essential for the thus formed stability of ApoA1, and the nascent pre-β-HDL particle enters into circulation and is an efficient acceptor of cellular cholesterol from peripheral cells such as macrophages. Atherosclerotic plaque-associated lipid-laden macrophage foam cells efflux cholesterol and phospholipids via ABCA1 to pre-β-HDL. Bulk efflux of cholesterol from macrophages occurs via another transporter, ABCG1, and is readily esterified in the HDL particle by the associated enzyme lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase. Scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI), present in the macrophages, brings about bidirectional movement of cholesterol and can potentially contribute to net efflux under certain conditions. In the plasma compartment, cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) facilitates the transfer of cholesteryl esters (CE) from HDL to LDL. Since such transfer decreases HDL-C, inhibition of CETP is being considered as a viable therapeutic target for raising HDL-C [13]. However, it is important to emphasize that CETP determines which lipoprotein particle, LDL or HDL, brings CE back to the liver. Mice lack CETP, thus HDL is the main lipoprotein particle that brings CE back to the liver. By contrast, in humans (who express CETP) both LDL and HDL return CE to the liver and their relative contribution can vary.

Figure 1. Current concepts in high-density lipoprotein metabolism.

ABCA1: ATP-binding cassette transporter A1; ABCG1: ATP-binding cassette transporter G1; ACAT1: Acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-1; ApoA1: Apolipoprotein A1; CE: Cholesteryl ester; CEH: Cholesteryl ester hydrolase; FC: Free cholesterol; LDLR: LDL receptor; SR-A: Scavenger receptor A; SR-BI: Scavenger receptor BI; TG: Triglyceride.

While LDL is taken up by the liver via the LDL receptor (LDLR), HDL binds to its receptor SR-BI and selectively delivers its core CE. A recent study has also demonstrated that hepatic CD36 facilitates selective uptake of HDL-CE as well as the uptake of HDL holoparticles [14]. In addition, Fabre et al. demonstrated SR-BI independent uptake of HDL by the liver via the purinergic receptor P2Y, G protein-coupled, 13 (P2Y13) receptor [15]. Following CE delivery via any of these hepatic receptors, lipid-poor HDL remnants thus generated (which are small and dense) are rapidly converted in the plasma to larger HDL2 particles, presumably by acquiring more cholesterol from the peripheral tissues [16,17]. Failure to effectively lipidate newly synthesized ApoA1 or HDL remnants targets them for degradation in the kidneys via cubilin, an endocytic receptor that is expressed on the apical surfaces of kidney proximal tubule cells [18]. Thus, pre-β HDL has two metabolic fates in vivo – rapid removal from plasma and catabolism by the kidney or remodeling to mediumsized HDL – determined by the amount of lipid associated with the pre-β particle [19]. Therefore, HDL metabolism occurs by coordinated action of multiple tissues and the atheroprotective effects of HDL are due to its ability to facilitate transport of cholesterol from plaque-associated macrophage foam cells to the liver, consequently reducing the lipid burden of the plaques. One critical aspect that is rarely emphasized is that the plasma HDL-C that is routinely measured represents merely a ‘snap-shot’ of the amount of cholesterol associated with HDL particles and does not report on the ability of HDL to facilitate RCT. Direct measurement of the ability of HDL to facilitate cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells is the only way to determine HDL functionality with respect to its role in RCT.

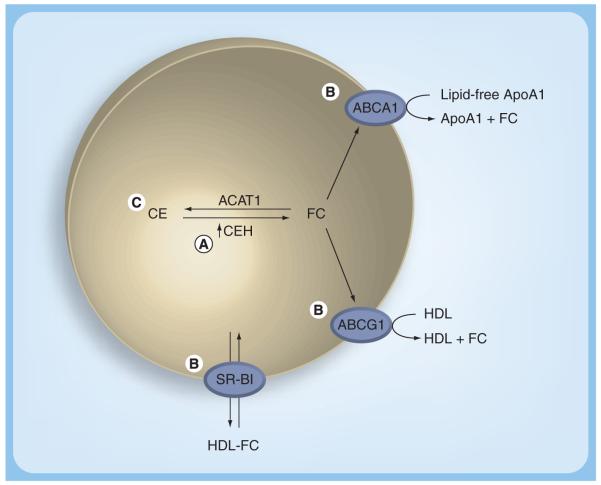

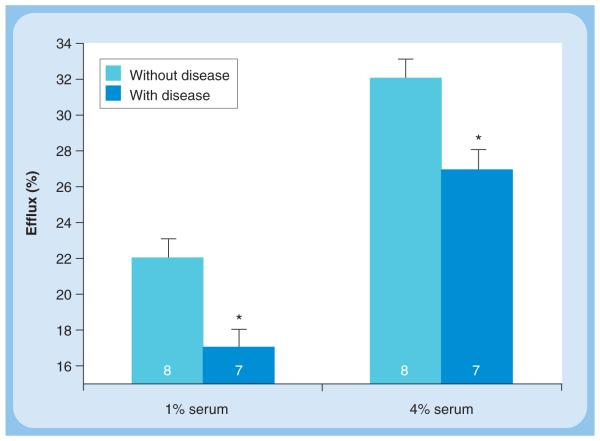

To develop a method for the determination of cholesterol efflux potential of HDL or serum, several methodological and physiological issues need to be considered (Figure 2). The cell system used must express all the relevant genes for the various functional pathways for cholesterol efflux as they exist in macrophages in vivo. Since cholesterol is stored in macrophage foam cells as CEs but it is effluxed as free or unesterified cholesterol and hydrolysis of intracellular CEs is the rate-limiting step in cholesterol efflux, the cells used should express the necessary cholesterol ester hydrolase (CEH; detailed in the next section and reviewed elsewhere [20]). Earlier studies have used Fu5AH, a hepatoma cell line, to evaluate the cholesterol efflux potential of human serum [21]. However, these cells are predominantly SR-BI expressing and do not truly represent the efflux pathways operational in macrophages. Furthermore, in most studies, efflux of cholesterol from these cells is studied after the cells are loaded with unesterified cholesterol and not CE, which is the physiological storage form. Recently, Adorni et al. described significant differences between the cholesterol efflux obtained using Fu5AH and mouse peritoneal macrophages [22]. We have recently developed and described a human monocyte/macrophage cell line (THP1-CEH) overexpressing human macrophage CEH [23]. Cholesterol efflux by all known pathways was demonstrated in this cell line. In a pilot study we compared the cholesterol efflux potential of serum obtained from subjects with established CVD to that of normal individuals with no disease. Despite comparable plasma lipid profiles, there was a significantly reduced cholesterol efflux to serum from patients with established CVD (Figure 3). These data provide the first evidence that HDL or serum efflux potential is likely to be a better predictor of CVD and underscores the need for the development and validation of appropriate assay systems to quantify cholesterol efflux potential in vitro or RCT in vivo. Large clinical trials would then be required to establish the risk-predictive value of serum efflux capacity/potential. It is noteworthy that impaired serum capacity to induce cholesterol efflux is observed in diabetic nephropathy [24] and is related to endothelial dysfunction in T2DM [25]. Furthermore, chronic inflammation, which is an important component of atherogenesis, is also associated with reduced serum cholesterol efflux capacity [26]. Although these studies illustrate the importance of evaluating the functionality of HDL with respect to its ability to facilitate cholesterol efflux from macrophages, they also underscore the significance of a detailed understanding of intracellular processes involved in regulating cellular cholesterol levels.

Figure 2. Essential components of the cell system for the determination of cholesterol efflux potential/capacity of serum or high-density lipoprotein from human subjects.

(A) Since CEH-mediated hydrolysis is the obligatory first and also the rate-limiting step in efflux of unesterified or free cholesterol, the cell system used should overexpress CEH to ensure that efflux of cholesterol is truly dependent on the capacity of the extracellular acceptor (serum or HDL). (B) The cells should express the cholesterol transporters (ABCA1 and ABCG1) relevant to macrophage foam cells. (C) Cholesterol that is effluxed and monitored should arise from a pool of CE, a storage form that is present in macrophage foam cells under physiological conditions.

ABCA1: ATP-binding cassette transporter A1; ABCG1: ATP-binding cassette transporter G1; ACAT1: Acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-1; ApoA1: Apolipoprotein A1; CE: Cholesteryl ester; CEH: Cholesteryl ester hydrolase; FC: Free cholesterol; SR-BI: Scavenger receptor BI.

Figure 3. Decreased ability of serum from patients with established cardiovascular disease to mediate cholesterol efflux from THP1-cholesteryl ester hydrolysis cells.

THP1-CEH cells were differentiated into macrophages by the addition of PMA. Differentiated macrophages were labeled with [3H]-cholesterol (2 μCi/ml) and loaded by incubating with acetylated LDL (50 μg/ml) for 48 h. Following a 24-h equilibration in serum-free medium, cholesterol efflux was initiated by the addition of either 1 or 4% of serum obtained from normal subjects or patients with established cardiovascular disease to the culture medium. Efflux of [3H]-cholesterol in the culture medium was determined at 3 and 6 h. Cells were lysed at the end of 6 h and total incorporation of radioactivity was determined. Percent efflux was calculated (dpm in culture medium/total incorporation × 100) and data (mean ± SD) for 6 h is shown; number of subjects in each group is indicated within the bars. The HDL-cholesterol levels were 62.9 ± 10.3 mg/dl for subjects without disease and 52.3 ± 7.67 mg/dl for subjects with disease. *p < 0.05.

Macrophage cholesterol homeostasis

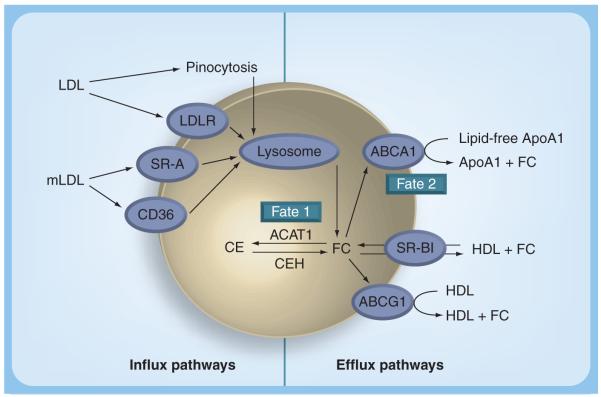

Cholesterol homeostasis in macrophages and other peripheral cells is maintained by a balance between the influx and efflux pathways (Figure 4). Cholesterol influx occurs by receptor- and nonreceptor-mediated-uptake of both normal and modified lipoproteins. While the uptake of LDLs via the LDL receptor is limited due to feedback inhibition of LDL receptor expression by cellular cholesterol levels, modified LDL uptake by scavenger receptors, namely scavenger receptor A (SR-A) and CD36, is largely unregulated and contributes substantially to foam cell formation. In addition, nonreceptor-mediated uptake pathways such as phagocytosis of aggregated LDLs and macropino cytosis of native [27-29] or modified LDLs [30] can also potentially contribute to lipid accumulation in macrophage foam cells. CEs associated with the lipoproteins are hydrolyzed in late endosomes/lysosomes to release free cholesterol (FC), which then traffics to and integrates into the plasma membrane [31]. Excess membrane cholesterol and a fraction of LDL-derived FC is transported to the endoplasmic reticulum where it is re-esterified by acyl coenzyme A :cholesterol acyltransferase-1 (ACAT1) and stored in cytoplasmic lipid droplets. While this re-esterification of cholesterol is initially beneficial to the cells in preventing the FC-associated cell toxicity, under conditions of unregulated or increased uptake of modified LDL it leads to an excessive accumulation of CE present as cytoplasmic lipid droplets, giving the cells their characteristic ‘foamy’ appearance. Cellular CEs undergo a constant cycle of hydrolysis and re-esterification (cholesteryl ester cycle) with a half-life of 24 h. Brown et al. demonstrated for the first time that this hydrolysis is extralysosomal and defined the ‘need’ for a neutral cholesteryl ester hydrolase (CEH) [32]. CEH releases FC from the lipid droplet-associated CE that can either be re-esterified again by ACAT-1 (fate 1) or removed from the cells by extracellular acceptor-mediated cholesterol efflux (fate 2). This acceptor-mediated FC efflux is the major mechanism for the removal of cellular cholesterol and is critical in preventing foam cell formation and atherosclerotic lesion development. Neutral CEH-mediated hydrolysis of cellular CE therefore represents the obligatory first step in FC efflux and is increasingly being recognized as the rate-limiting step [33]. Macrophages with high neutral CEH activity accumulate fewer cholesterol esters in the presence of atherogenic β-migrating very LDLs (β-VLDL) in comparison to macrophages with low CEH activity [34]. Animal models of atherosclerosis, such as the hypercholesterolemic rabbit and the White Carneau pigeon, appear to possess macrophages in which stored cholesterol esters are resistant to hydrolysis and subsequent mobilization [35,36]. Hence, CEH activity may be a limiting factor in the mobilization of cholesterol esters from foam cells, and therefore may play a role in determining the susceptibility to atherosclerosis.

Figure 4. Macrophage cholesterol homeostasis.

The influx pathways include uptake of native LDL either via LDLR or by macropinocytosis; uptake of aggregated LDL by phagocytosis (not shown); and receptor-mediated uptake of mLDL via scavenger receptors CD36 and SR-A. Following degradation in the lysosomes, the released FC is re-esterified by ACAT-1 and stored in the cytoplasm as CEs. For efflux, stored CEs are hydrolyzed by a neutral CEH and the release FC is effluxed to extracellular acceptors ApoA1 (via ABCA1) or to nascent HDL (via ABCG1). SR-BI facilitates bidirectional movement of cholesterol. FC within the macrophage, therefore, has two fates – fate 1 is the re-esterification by ACAT1 and fate 2 is the efflux to extracellular acceptors.

ABCG1: ATP-binding cassette transporter G1; ACAT1: Acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-1; ApoA1: Apolipoprotein A1; CE: Cholesteryl ester; CEH: Cholesteryl ester hydrolase; FC: Free cholesterol; LDLR: LDL receptor; mLDL: modified LDL; SR-A: Scavenger receptor A; SR-BI: Scavenger receptor BI.

Cholesterol generated by CEH-mediated hydrolysis of stored CEs is transported to extracellular acceptors such as lipid-poor ApoA1 or HDL by ABCA1 and ABCG1, respectively. These transporters are responsible for the major part of macrophage cholesterol efflux to serum or HDL in macrophage foam cells, but other less efficient pathways such as passive efflux are also involved [22]. While selective deletion of ABCA1 in macrophages [37] and overexpression of ABCG1 [38] did not significantly modulate atherogenesis, combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes atherosclerosis in mice [39]. Mice with human ABCA1 bacterial artificial chromosome show reduced atherosclerosis [40] but liver-specific overexpression of ABCA1 promoted increased production of proatherogenic lipoproteins and enhanced atherosclerosis [41]. Further characterization of the effects of overexpression of these cholesterol transporters is required before focusing on the development of strategies to measure their expression/activity, with the objective of assessing CVD risk ([42] reviews the potential of these transporters as possible therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis).

Mobilization of intracellular CE: role of CEH

Since intracellular CE originates by ACAT-1-mediated esterification of lipoprotein-derived cholesterol, the first logical step to attenuate CE accumulation in foam cells was to target inhibition of ACAT and pharmacological inhibition of ACAT as a means to prevent or attenuate foam cell formation was extensively pursued [43-46]. However, Perrey et al. showed increased plaque formation by preferential pharmacological inhibition of macrophage ACAT or ACAT-1 in mouse and rabbit models of atherosclerosis [47]. Disruption of ACAT-1 was shown to result in marked systemic abnormalities in lipid homeostasis in hypercholesterolemic ApoE-deficient and LDL-receptor-deficient mice, leading to extensive deposition of FC in the skin and brain [48,49]. Furthermore, Fazio et al. reported increased atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice lacking ACAT-1 in macrophages [50]. Although the reduced content of macrophages and neutral lipids in lesions lacking ACAT1 may have beneficial effects on lesion stability [51], the increase in lesion area and the systemic lipid abnormalities observed in ACAT-1-deficient mice suggest that deficiency of ACAT-1 could have detrimental effects [52].

An alternative approach to reducing cellular CE content would be to enhance CE hydrolysis by increasing CEH activity. While intuitively similar with respect to reducing the cellular CE content, these two approaches are fundamentally different. Under conditions of ACAT inhibition, a decrease in cellular FC can only be achieved by extracellular acceptor-mediated FC efflux (fate 2; Figure 4). Thus, ACAT inhibition results in an increase in cellular FC accumulation, both in the plasma membrane and in the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in toxicity, ER stress and apoptosis. These effects of ACAT inhibition and associated FC-induced toxicity can be partially relieved by increasing the concentration of extracellular cholesterol acceptors [53]. On the other hand, with increased CEH-mediated CE hydrolysis, the resulting FC can either be re-esterified by ACAT (fate 1; Figure 4) or effluxed from the cell (fate 2; Figure 4). Thus, even under conditions of limiting acceptor concentration, there will be no increase in cellular FC because FC released by CEH-mediated hydrolysis can be re-esterified by functional ACAT1 [54].

We have cloned and characterized human macrophage CEH cDNA and demonstrated the expression of the mRNA for this enzyme in the THP1 human monocyte/macrophage cell line, as well as in human peripheral blood monocyte/macrophages [55]. Transient transfection of this cDNA resulted in a significant increase in CE hydrolytic activity, authenticating the cDNA clone as that of a bonafide neutral CEH (gene name Ces1). This enzyme associated with the surface of lipid droplets in lipid-laden cells (its physiological substrate) and hydrolyzed CE present in lipid droplets [56]. Overexpression of this enzyme resulted in mobilization of cellular CEs [54], demonstrating its role in regulating cellular CE accumulation. Stable overexpression of this CEH in the human monocyte/macrophage cell line, THP1, resulted in significantly higher FC efflux to ApoAI, HDL and serum, demonstrating that FC released by CEH-mediated hydrolysis of intracellular CE is available for efflux by all known pathways [23]. Taken together, these data support the role of this enzyme in regulating macrophage CE content and FC efflux. Consistent with these data from our laboratory, Crow et al. recently demonstrated an increase in CE accumulation and foam cell formation in human THP1 macrophages by pharmacological inhibition of CEH [57], providing further support for CEH overexpression as a potentially important target for attenuating cellular CE content.

CEH-mediated reduction in foam cell formation & atherosclerosis

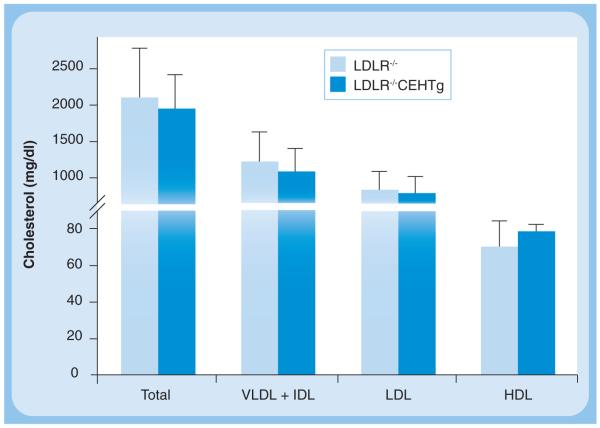

The description thus far establishes the role of CEH in enhancing cellular CE mobilization, and thus reducing foam cell formation. However, the physiologically and clinically relevant question is whether enhancing CEH expression will attenuate atherogenesis and reduce plaque formation? Towards this goal we developed macrophage-specific CEH transgenic mice where expression of human macrophage CEH was driven by the SR-A promoter–enhancer complex. Peritoneal macrophages from CEH transgenic mice accumulated less CE due to enhanced FC efflux to extracellular cholesterol acceptors. Significant attenuation of high-fat, high-cholesterol diet-induced atherosclerosis was noted in CEH transgenic mice crossed into an LDLR−/− background and the underlying mechanism was enhanced in vivo RCT, resulting in increased elimination of cholesterol from the body as bile acids in the feces [58]. In addition to a significant reduction in atherosclerosis, transgenic expression of CEH also led to a significant decrease in lesion necrosis [58]. It needs to be emphasized that these atheroprotective effects were noted without any significant changes in plasma lipoprotein profiles and no significant increase in HDL-C (Figure 5), clearly establishing the need for directing the focus on processes that are central to enhancing macrophage cholesterol efflux and in vivo RCT rather than the lipoprotein cholesterol content per se. Enhancing CEH expression/activity therefore represents a novel target to attenuate atherogenesis. An emerging question is whether CEH deficiency is a risk factor for the development of CVD? Currently, no genetic CEH deficiency or loss-of-function mutants for macrophage CEH have been reported and future studies are likely to provide additional information.

Figure 5. Unchanged levels of cholesterol associated with plasma lipoproteins in macrophage-specific cholesteryl ester hydrolase transgenic mice despite a significant (>50%) reduction in atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Plasma was obtained from non-fasted LDLR−/− (light blue bars) and LDLR−/−CEHTg (dark blue bars) mice after 16 weeks of Western high-fat high-cholesterol diet feeding. An aliquot of the plasma from each animal was applied to Superose-6 FPLC column and cholesterol content of individual lipoproteins determined by an on-line assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, for n = 6.

IDL: Intermediate-density lipoprotein; LDLR: LDL receptor.

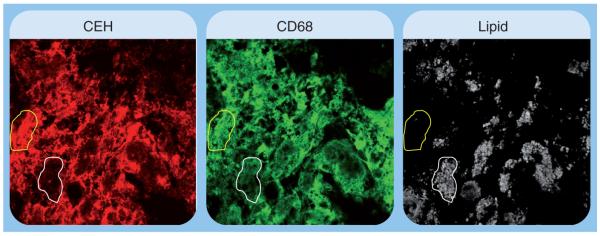

Based on the central role of CEH in CE mobilization and atherogenesis, it can be logically deduced that plaque-associated macrophage foam cells may exhibit lower expression/activity of CEH that would reduce the normal or homeostatic levels of CE mobilization. It is noteworthy that immunohistochemical detection of CEH in human carotid artery plaques showed decreased CEH staining associated with CD68-positive macrophages that contained high amounts of neutral lipids (Figure 6). This is consistent with the role of CEH in enhancing CE mobilization and consequently reducing the CE content of plaques as observed in CEH transgenic mice [58]. Studies examining the direct correlation between CEH levels (either by immunohistochemical or molecular methods) and CE accumulation in plaque-associated foam cells will further define this inverse relationship between intracellular CEH and atherogenesis.

Figure 6. Decreased expression of cholesteryl ester hydrolase in lipid-laden foam cells associated with human atherosclerotic plaque.

Human carotid artery lesions were stained for CEH (red) and macrophages (CD68, green). The region outlined in yellow shows staining for CEH as well as macrophages, and was not associated with lipid accumulation. The area outlined in white showed minimal staining for CEH, but was stained for macrophages and showed high lipid content.

CEH: Cholesteryl ester hydrolase.

As shown in Figure 1, HDL delivers CEs to the liver via its receptor SR-BI for the final elimination in bile and feces. Intracellular hydrolysis of these CEs is required prior to secretion of free or unesterified cholesterol into bile of conversion into bile acids. Hepatic CEH is thought to play an important role in this process and adenovirus-mediated transient overexpression of CEH in the liver leads to an increase in in vivo RCT and flux of cholesterol from macrophages to feces [59]. Studies are in progress to determine the role of liver-specific transgenic expression of CEH on atherosclerosis, and whether overexpression in macrophages and the liver will have an additive effect on attenuation of athero genesis. Taken together with the beneficial effects of macrophage-specific overexpression of CEH, these data clearly establish CEH as a novel therapeutic target whereby enhancing CEH expression/activity in two different organ beds can substantially reduce the development of atherosclerotic plaques.

Macrophage CE content & inflammation

In addition to foam cell formation and atherogenesis, accumulation of CEs also results in a significant increase in inflammation. Fazio and Linton proposed a feedback loop linking macrophage cholesterol balance and inflammatory mediators, and suggested that a primary defect in cellular cholesterol balance may induce changes in the inflammatory status of the macrophage [60]. Consistently, under conditions of enhanced cholesterol accumulation – for example by deficiency of cholesterol transporter ABCA1 – there was a marked increase in TNF-α secretion from macrophages [61]. By contrast, overexpression of ApoA1, which enhances cholesterol removal and decreases cellular cholesterol levels, resulted in attenuated response to proinflammatory insult by LPS [62]. Thus, the inability of macrophages to efficiently efflux excess cholesterol, either due to an inability to generate FC for efflux (CEH deficiency) or due to the lack of appropriate or functional extracellular acceptor (namely HDL), would result not only in foam cell formation but also in the generation of a proinflammatory cell that provides the milieu for the perpetuation of this process. It is noteworthy that macrophages from ldlr−/−Abca1−/− mice with an 80-fold increase in cellular CE content display an exaggerated inflammatory response [63]. Several recent studies have shown that ABCA1 and ABCG1 modulate macrophage expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as lymphocyte-proliferative responses, and these effects are related to their ability to promote cholesterol efflux [64]. A recent clinical study demonstrated the beneficial effects of reconstituted HDL infusions that enhance cholesterol efflux from cells on suppression of inflammation [65], underscoring the importance of cholesterol removal in modulating inflammatory processes.

Macrophage-specific transgenic overexpression of CEH significantly reduced the cellular CE content and consequently reduced the expression of proinflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1 and GM-CSF [66]. The resulting decrease in systemic inflammation led to an attenuated infiltration of macrophages into the adipose tissue and adipose tissue inflammation [66]. Adipose tissue inflammation and circulating cytokines, namely IL-1β [67], IL-6 [68] and TNF-α [69], collectively contribute to insulin resistance associated with obesity. IL-1β is the primary cytokine that not only regulates its own production by an auto feed-forward loop but also regulates the production of other cytokines including IL-6 [70]. IL-1β and IL-6 are thought to perturb insulin signaling, including insulin-dependent Akt phosphorylation [71,72], and recent evidence suggests that some of the effects of TNF-α may be mediated by its ability to induce IL-6 [73]. Macrophages are the primary source of IL-1β and macrophage-derived IL-1β production in insulin-sensitive organs such as adipose tissue leads to progression of inflammation and induction of insulin resistance in obesity [74]. IL-1β production and secretion have also been reported from pancreatic islets, and insulin-producing β-cells within pancreatic islets are especially prone to IL-1β-induced destruction and loss of function [74]. Attenuated levels of circulating IL-1β and/or other cytokines observed in macrophage-specific CEH-transgenic mice thus leads to improved insulin sensitivity in these mice [66].

Renal dysfunction is also associated with excessive CVD; however, it remains uncertain how renal dysfunction/failure imparts this heightened risk. Oxidative stress and inflammation have recently been considered as important factors relevant to CVD in the setting of chronic kidney disease. For example, in patients with chronic kidney disease, the highest tertiles of high-sensitivity C-reactive proteins and IL-6 were each associated with doubling in the risk for sudden cardiac death compared with the lowest tertiles [76,77]. Notably, the impact of these circulating markers of inflammation on cardiovascular deaths was independent of traditional risk factors [78,79]. Perturbation of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis is now being regarded as the possible mechanism for the increase in inflammation and the increased CVD risk associated with chronic kidney disease. Recognizing this importance of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis, Yamamoto and Kon have suggested that strategies that promote macrophage cholesterol efflux and subsequent elimination of lipids offer the possibility of a novel target for lessening atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease [79]. The presence of dysfunctional HDL in patients with chronic kidney disease was reported by Moraldi et al. and it remains to be seen whether attenuation of HDL functionality or impairment of intracellular mechanisms is responsible for aberrant macrophage cholesterol homeostasis [80].

Thus, it is apparent that one of the common mechanisms underlying multiple inflammation-linked pathologies, including atherosclerosis, T2DM and chronic kidney disease is dysfunctional macrophage cholesterol homeostasis. Enhanced removal of lipids from the macrophages, either by increasing CEH or by improving HDL function, results in attenuation of these diseases. Taken together with the observed reduction in systemic inflammation following infusion of reconstituted HDL in T2DM subjects [65], the role of macrophage CE mobilization in regulating inflammation and linked pathologies cannot be overstated.

Expert commentary

The presence of significant residual risk for future cardiac events despite an aggressive reduction in LDL-C highlights the urgent need to re-evaluate the existing paradigm of risk factors for CVD. Heightened awareness of the protective role of HDL is a shift in the correct direction. However, certain conceptual advances are essential not only for a better understanding but also for the development of novel therapies.

It is important to make the distinction between HDL and HDL-C. Currently measured HDL-C only represents the amount of cholesterol associated with the circulating HDL particle at the time of sampling. It may be necessary to measure the HDL particle number and/or ApoA1 levels associated with HDL.

High-density lipoprotein functionality is likely to be more relevant in risk prediction than HDL-C or HDL particle number. The ability of HDL to promote cholesterol efflux as well as attenuate inflammation and/or oxidation of LDL needs to be evaluated.

Since HDL is only an extracellular acceptor of unesterified or FC (although excess cholesterol is stored as CE within the macrophage foam cell), the intercellular hydrolysis of stored CE is an important parameter that requires evaluation. In this regard, expression, activity and variations in macrophage CEH should be considered when estimating risk for CVD.

The concept that the beneficial role of decrease in macrophage cholesterol content is solely to reduce plaque burden should be revised/refined to include the beneficial effects of attenuating systemic and adipose tissue inflammation. This change is essential to considering targeted approaches to reduce macrophage cholesterol burden to collectively alleviate inflammation-linked pathologies such as T2DM and chronic kidney disease in addition to CVD.

It is fairly easy to envision significant progress in the aforementioned areas in the near future, with recent studies giving encouraging results. In an effort to achieve plaque regression by enhancing the movement of cholesterol from artery wall-associated foam cell, ApoA1-Milano (a variant of ApoA1 with a higher cholesterol efflux capacity) was infused intravenously, resulting in a significant decrease in plaque volume [81]. While this study represents progress in the right direction, ApoA-I is a large protein that needs to be administered intravenously and its large-scale synthesis is cost prohibitive. ApoA-I mimetic peptides have been developed that are much smaller than ApoA-I and far more effective. These mimetic peptides improve LDL and HDL composition and function, and reduce lesion formation in animal models of atherogenesis [82]. These mimetics also increase cholesterol efflux and restore HDL function [83-86]. However, efficacy of these mimetics in large clinical studies remains to be evaluated.

While the physiological function of macrophages and hepatic CEH, and their role in attenuation of diet-induced atherosclerosis and cholesterol elimination from the body is well established as described earlier, currently no information is available on interventions that can enhance the expression or activity of this enzyme in vivo. Furthermore, no dedicated study has thus far attempted to establish an association between CEH expression and CVD or risk for CVD. Combined efforts from a basic research standpoint to understand CEH regulation in vivo and from a pharmacological standpoint to identify molecules that can enhance the activity of this enzyme are likely to lead to the development of strategies to enhance macrophage CE mobilization and cholesterol elimination from the body.

Reduction in macrophage CE content, whether by HDL-mediated removal of unesterified cholesterol or by increased hydrolysis of stored CE by CEH to facilitate efflux, should be recognized as a novel mechanism to attenuate inflammation and linked pathologies. The convergence of favorable outcomes for diseases such as T2DM, chronic renal failure and CVD on successful removal of CE from macrophages underscores the importance of targeted modulation of this process to collectively alleviate pathologies associated with the metabolic syndrome.

Five-year view

It is reasonable to expect that a lag time will exist between the advances made in the laboratory and clinical practice, primarily due to the required rigorous testing and evaluation of any new concept or therapeutic strategy. However, the first step in closing this gap is the recognition of the need to change or modify the existing dogma. Identification of the residual risk, importance of assessing the functionality of HDL and the role of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis, as well as CEH, are some of the advancements that are expected to change the current reliance on plasma lipid profiles for risk prediction and assessment in the next 5 years. Nonetheless, the progress will be contingent on the development of new methods to evaluate HDL functionality and macrophage CEH expression/activity. HDL-functionality assays are likely to be cell based as described earlier, and molecular approaches such as real-time PCR will be needed for the measurement of CEH expression. While these techniques are effectively performed in research laboratories, adaptation for large-scale clinical use will be the most important challenge in implementing these new concepts as diagnostic tools.

The development of new therapeutic strategies will largely depend on two important issues:

Determination of mechanisms to increase HDL functionality and CEH expression;

Successful development of methods to measure these two parameters so that these can be used as potential end points while evaluating the efficacy of a pharmacological agent.

A detailed understanding of transcriptional, translational or post-translational regulation of CEH expression/activity in vivo is most likely to identify endogenous mechanisms that can be modulated to enhance endogenous CEH activity and, thus, CE mobilization. Promising results have been obtained by the use of ApoA1 mimetic peptides and similar advances will potentially provide new ways to enhance high-density lipoprotein functionality.

Acknowledgments

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The research in Shobha Ghosh’s laboratory is supported by funding from the NIH-NHLBI (grant no. HL069946 and HL097346) and American Diabetes Association. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@expert-reviews.com

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest •• of considerable interest

- 1.D’Agostino RB, Russell MW, Huse DM, et al. Primary and subsequent coronary risk appraisal: new results from the Framingham study. Am. Heart J. 2000;139(2 Pt 1):272–281. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.96469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2003;290(7):891–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni H, Coady S, Rosamond W, et al. Trends from 1987 to 2004 in sudden death due to coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am. Heart J. 2009;157(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Executive Summary of the Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. Treating to New Targets (TNT) Investigators Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352(14):1425–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. • First clear demonstration of residual cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

- 7.Fruchart JC, Sacks F, Hermans MP, et al. The Residual Risk Reduction Initiative: a call to action to reduce residual vascular risk in patients with dyslipidemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008;102(10 Suppl.):1K–34K. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(08)01833-X. •• Position paper detailing the Residual Risk Initiative (R3I).

- 8.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am. J. Med. 1977;62(5):707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assmann G, Schulte H, von Eckardstein A, Huang Y. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a predictor of coronary heart disease risk. The PROCAM experience and pathophysiological implications for reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124:S11–S20. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05852-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Antiatherogenic function of HDL particle subpopulations: focus on antioxidative activities. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2010;21(4):312–318. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833bcdc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman MJ. Therapeutic elevation of HDL-cholesterol to prevent atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;111(3):893–908. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinecke JW. The HDL proteome: a marker – and perhaps mediator – of coronary artery disease. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:S167–S171. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800097-JLR200. •• Pioneering work demonstrating the complexity of the proteins associated with HDL particles and their physiological role.

- 13.Chapman MJ, Le Goff W, Guerin M, Kontush A. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein: at the heart of the action of lipid-modulating therapy with statins, fibrates, niacin, and cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31(2):149–164. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brundert M, Heeren J, Merkel M, et al. Scavenger receptor CD36 mediates uptake of high density lipoproteins by tissues in mice and by cultured cells. J. Lipid Res. 2011 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M011981. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.M011981. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabre AC, Malaval C, Ben Addi A, et al. P2Y13 receptor is critical for reverse cholesterol transport. Hepatology. 2010;52:1477–1483. doi: 10.1002/hep.23897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb NR, Cai L, Ziemba KS, et al. The fate of HDL particles in vivo after SR-BI–mediated selective lipid uptake. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:1890–1898. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200173-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb NR, De Beer MC, Asztalos BF, et al. Remodeling of HDL remnants generated by scavenger receptor class B type I. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:1666–1673. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400026-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozyraki R, Fyfe J, Kristiansen M, et al. The intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor, cubilin, is a high affinity apolipoprotein A-I receptor facilitating endocytosis of high-density lipoprotein. Nat. Med. 1999;5:656–661. doi: 10.1038/9504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JY, Lanningham-Foster L, Boudyguina EY, et al. Pre-β high density lipoprotein has two metabolic fates in human apolipoprotein A-I transgenic mice. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:716–728. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300422-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh S, Zhao B, Bie J, Song J. Macrophage cholesteryl ester mobilization and atherosclerosis. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2010;52(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.10.002. • Detailed review of intracellular CE hydrolysis and CEH characterization.

- 21.Jian B, de la Llera-Moya M, Royer L, et al. Modification of the cholesterol efflux properties of human serum by enrichment with phospholipid. J. Lipid Res. 1997;38:734–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adorni MP, Zimetti F, Billheimer JT, et al. The roles of different pathways in the release of cholesterol from macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48(11):2453–2462. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700274-JLR200. • Identification and quantification of cholesterol efflux by various pathways.

- 23.Zhao B, Song J, St Clair RW, Ghosh S. Stable over-expression of human macrophage cholesteryl ester hydrolase (ceh) results in enhanced free cholesterol efflux from human thp1-macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292(1):C405–C412. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00306.2006. • Development of a human macrophage cell system suitable for measuring efflux potential.

- 24.Zhou H, Tan KC, Shiu SW, Wong Y. Cellular cholesterol efflux to serum is impaired in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2008;24(8):617–623. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou H, Shiu SW, Wong Y, Tan KC. Impaired serum capacity to induce cholesterol efflux is associated with endothelial dysfunction in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2009;6(4):238–243. doi: 10.1177/1479164109344934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ripollés Piquer B, Nazih H, Bourreille A, et al. Altered lipid, apolipoprotein, and lipoprotein profiles in inflammatory bowel disease: consequences on the cholesterol efflux capacity of serum using Fu5AH cell system. Metabolism. 2006;55(7):980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruth HS. Sequestration of aggregated low-density lipoproteins by macrophages. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002;13(5):483–488. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruth HS, Jones NL, Huang W, et al. Macropinocytosis is the endocytic pathway that mediates macrophage foam cell formation with native low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;1280(3):2352–2360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruth HS, Huang W, Ishii I, Zhang WY. Macrophage foam cell formation with native low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(37):34573–34580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi SH, Harkewicz R, Lee JH, et al. Lipoprotein accumulation in macrophages via toll-like receptor-4-dependent fluid phase uptake. Circ. Res. 2009;104:1355–1363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabas I. Cholesterol and phospholipid metabolism in macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1529(1–3):164–174. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown MS, Ho YK, Goldstein JL. The cholesteryl ester cycle in macrophage foam cells. Continual hydrolysis and re-esterification of cytoplasmic cholesteryl esters. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255(19):9344–9352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothblat GH, de la Llera-Moya M, Favari E, Yancey PG, Kellner-Weibel G. Cellular cholesterol flux studies: methodological considerations. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00713-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishii I, Oka M, Katto N, Shirai K, Saito Y, Hirose S. β-VLDL-induced cholesterol ester deposition in macrophages may be regulated by neutral cholesterol esterase activity. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1992;12:1139–1145. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathur SN, Field FJ, Megan MB, Armstrong HL. A defect in mobilization of cholesteryl esters in rabbit macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;834:48–57. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yancey PG, St. Clair RW. Mechanism of the defect in cholesteryl ester clearance from macrophages of atherosclerosis-susceptible White Carneau pigeons. J. Lipid Res. 1994;35:2114–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunham LR, Singaraja RR, Duong M, et al. Tissue-specific roles of ABCA1 influence susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29(4):548–554. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burgess B, Naus K, Chan J, et al. Overexpression of human ABCG1 does not affect atherosclerosis in fat-fed ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28(10):1731–1737. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yvan-Charvet L, Ranalletta M, Wang N, et al. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117(12):3900–3908. doi: 10.1172/JCI33372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singaraja RR, Fievet C, Castro G, et al. Increased ABCA1 activity protects against atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:35–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joyce CW, Wagner EM, Basso F, et al. ABCA1 overexpression in the liver of LDLr-KO mice leads to accumulation of pro-atherogenic lipoproteins and enhanced atherosclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(44):33053–33065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye D, Lammers B, Zhao Y, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 and G1, HDL metabolism, cholesterol efflux, and inflammation: important targets for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Curr. Drug. Targets. 2010 doi: 10.2174/138945011795378522. PubMed PMID: 21039336. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sliskovic DR, White AD. Therapeutic potential of ACAT inhibitors as lipid lowering and anti-atherosclerotic agents. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:194–199. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuda K. ACAT inhibitors as antiatherosclerotic agents. Med. Res. Rev. 1994;14:271–305. doi: 10.1002/med.2610140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuo M, Ito F, Konto A, Aketa M, Tomoi M, Shimomura K. Effect of FR145237, a novel ACAT inhibitor on atherogenesis in cholesterol fed and WHHl rabbits. Evidence for a direct effect on the arterial wall. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1259:254–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicolosi RJ, Wilson TA, Krause BR. The ACAT inhibitor, CI 1011 is effective in the prevention and regression of aortic fatty streak in hamsters. Atherosclerosis. 1998;137:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perrey S, Legendre C, Matsuura A, et al. Preferential pharmacological inhibition of macrophage ACAT increases plaque formation in mouse and rabbit models of atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2001;155:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Accad M, Smith S, Newland D, et al. Massive xanthomatosis and altered composition of atherosclerotic lesions in hyperlipidemic mice lacking acyl CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase-1. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:711–719. doi: 10.1172/JCI9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yagu H, Kitamine T, Osuga J, et al. Absence of ACAT-1 attenuates atherosclerosis but causes dry eye and cutaneous xanthomatosis in mice with congenital hyperlipidemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:21324–21330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fazio S, Major AS, Swift LL, et al. Increased atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice lacking ACAT1 in macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:163–171. doi: 10.1172/JCI10310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bocan TM, Krause BR, Rosebury WS, et al. The ACAT inhibitor avasimbe reduces macrophages and matrix metalloproteinase expression in atherosclerotic lesion of hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arteioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000;20:70–79. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis: the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warner GJ, Stoudt G, Bamberger M, Johnson WJ, Rothblat GH. Cell toxicity induced by inhibition of acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase and accumulation of unesterified cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:5772–5778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghosh S, St Clair RW, Rudel LL. Mobilization of cytoplasmic CE droplets by over-expression of human macrophage cholesteryl ester hydrolase. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:1833–1840. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300162-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghosh S. Cholesteryl ester hydrolase in human monocyte/macrophage: cloning, sequencing and expression of full-length cDNA. Physiol. Genomics. 2000;2:1–8. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.2.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao B, Fisher BJ, St Clair RW, Rude LL, Ghosh S. Redistribution of macrophage cholesteryl ester hydrolase from cytoplasm to lipid droplets upon lipid loading. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:2114–2121. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500207-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crow JA, Middleton BL, Borazjani A, Hatfield MJ, Potter PM, Ross MK. Inhibition of carboxylesterase 1 is associated with cholesteryl ester retention in human THP-1 monocyte/macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1781(10):643–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao B, Song J, Chow WN, St Clair RW, Rudel LL, Ghosh S. Macrophage-specific transgenic expression of cholesteryl ester hydrolase significantly reduces atherosclerosis and lesion necrosis in Ldlr mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117(10):2983–2992. doi: 10.1172/JCI30485. •• First demonstration of a reduction in atherosclerosis by a targeted increase in macrophage CEH.

- 59.Zhao B, Song J, Ghosh S. Hepatic overexpression of cholesteryl ester hydrolase enhances cholesterol elimination and in vivo reverse cholesterol transport. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49(10):2212–2217. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800277-JLR200. • Identification of the role of hepatic CE hydrolysis in cholesterol elimination from the body.

- 60.Fazio S, Linton MF. The inflamed plaque: cytokine production and cellular cholesterol balance in the vessel wall. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001;88:12E–15E. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01717-9. • Establishes the link between cellular cholesterol homeostasis and inflammation.

- 61.Koseki M, Hirano K, Masuda D, et al. Increased lipid rafts and accelerated lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-α secretion in Abca1-deficient macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:299–306. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600428-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levine DM, Parker TS, Donnelly TM, Walsh A, Rubin AL. In vivo protection against endotoxin by plasma high density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:12040–12044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Francone OL, Royer L, Boucher G, et al. Increased cholesterol deposition, expression of scavenger receptors, and response to chemotactic factors in Abca1-deficient macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005;25:1198–1205. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166522.69552.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Tall AR. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30(2):139–143. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179283. •• Current understanding of the role of cholesterol efflux and modulation of immune responses and inflammation.

- 65.Patel S, Drew BG, Nakhla S, et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein increases plasma high-density lipoprotein anti-inflammatory properties and cholesterol efflux capacity in patients with Type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53:962–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bie J, Zhao B, Song J, Ghosh S. Improved insulin sensitivity in high fat- and high cholesterol-fed Ldlr−/− mice with macrophage-specific transgenic expression of cholesteryl ester hydrolase: role of macrophage inflammation and infiltration into adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(18):13630–13637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069781. •• Direct demonstration of improvement in insulin sensitivity by modulating macrophage cholesterol homeostasis.

- 67.Besedovsky HO, Del Rey A. Metabolic and endocrine actions of interleukin-1. Effects on insulin-resistant animals. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1990;594:214–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb40481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vozarova B, Weyer C, Hanson K, Tataranni P, Bogardus C, Pratley R. Circulating interleukin-6 in relation to adiposity, insulin action, and insulin secretion. Obes. Res. 2001;9:414–417. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hotamisligil G, Shargill N, Spiegelman B. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-α: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taishi P, Churchill L, De A, Obal F, Krueger JM. Cytokine mRNA induction by interleukin-1β or tumor necrosis factor alpha in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2008;1226:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lagathu C, Bastard JP, Auclair M, Maachi M, Capeau J, Caron M. Chronic interleukin-6 (IL-6) treatment increased IL-6 secretion and induced insulin resistance in adipocyte: prevention by rosiglitazone. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;311:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jager J, Grémeaux T, Cormont M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Interleukin-1β-induced insulin resistance in adipocytes through down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. Endocrinology. 2007;148:241–251. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alvarez B, Quinn LS, Busquets B, Quiles MT, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Tumor necrosis factor-α exerts interleukin-6-dependent and -independent effects on cultured skeletal muscle cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1542:66–72. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maedler K, Dharmadhikari G, Schumann DM, Størling J. Interleukin-1β targeted therapy for Type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2009;9:1177–1188. doi: 10.1517/14712590903136688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Honda H, Qureshi AR, Heimburger O, et al. Serum albumin, C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and fetuin a as predictors of malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in patients with ESRD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006;47:139–148. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soriano S, Gonzalez L, Martin-Malo A, et al. C-reactive protein and low albumin are predictors of morbidity and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease (CKD) 3–5 patients. Clin. Nephrol. 2007;67:352–357. doi: 10.5414/cnp67352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shah DS, Polkinhorne KR, Pellicano R, Kerr PG. Are traditional risk factors valid for assessing cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal failure patients? Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13:667–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parekh RS, Plantinga LC, Kao WH, et al. The association of sudden cardiac death with inflammation and other traditional risk factors. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1335–1342. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamamoto S, Kon V. Mechanisms for increased cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2009;18(3):181–188. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328327b360. •• Excellent review of the role of cholesterol homeostasis in determining the increased risk for CVD in chronic kidney disease.

- 80.Moradi H, Pahl MV, Elahimehr R, Vaziri ND. Impaired antioxidant activity of high-density lipoprotein in chronic kidney disease. Transl. Res. 2009;153(2):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nissen SE, Tsunoda T, Tuzcu EM, et al. Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(17):2292–2300. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2292. •• First clinical study to demonstrate regression of existing plaque by enhancing cholesterol efflux.

- 82.Vakili L, Hama S, Kim JB, et al. The effect of HDL mimetic peptide 4F on PON1. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;660:167–172. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-350-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith JD. Apolipoprotein A-I and its mimetics for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2010;11(9):989–996. •• Review of the current status of ApoA1 mimetics.

- 84.Sherman CB, Peterson SJ, Frishman WH. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides: a potential new therapy for the prevention of atherosclerosis. Cardiol. Rev. 2010;18(3):141–147. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181c4b508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.White CR, Datta G, Mochon P, et al. Vasculoprotective effects of apolipoprotein mimetic peptides: an evolving paradigm in HDL therapy. Vasc. Dis. Prev. 2009;6:122–130. doi: 10.2174/1567270000906010122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, Fogelman AM. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides and their role in atherosclerosis prevention. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2006;3(10):540–547. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]