Abstract

Background

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been considered as a promising treatment modality for gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). However, there have also been many debates regarding the efficacy and safety of this new approach. Results from experimental animal model study could help provide reliable information. This study was to investigate the safety and efficacy of CRS + HIPEC to treat gastric cancer with PC in a rabbit model.

Methods

VX2 tumor cells were injected into the gastric submucosa of 42 male New Zealand rabbits using a laparotomic implantation technique, to construct rabbit model of gastric cancer with PC. The rabbits were randomized into control group (n = 14), CRS alone group (n = 14) and CRS + HIPEC group (n = 14). The control group was observed for natural course of disease progression. Treatments were started on day 9 after tumor cells inoculation, including maximal removal of tumor nodules in CRS alone group, and maximal CRS plus heperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion with docetaxel (10 mg/rabbit) and carboplatin (40 mg/rabbit) at 42.0 ± 0.5°C for 30 min in CRS + HIPEC group. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). The secondary endpoints were body weight, biochemistry, major organ functions and serious adverse events (SAE).

Results

Rabbit model of gastric cancer with PC was successfully established in all animals. The clinicopathological features of the model were similar to human gastric PC. The median OS was 24.0 d (95% confidence interval 21.8 - 26.2 d ) in the control group, 25.0 d (95% CI 21.3 - 28.7 d ) in CRS group, and 40.0 d (95% CI 34.6 - 45.4 d ) in CRS + HIPEC group (P = 0.00, log rank test). Compared with CRS only or control group, CRS + HIPEC could extend the OS by at least 15 d (60%). At the baseline, on the day of surgery and on day 8 after surgery, the peripheral blood cells counts, liver and kidney functions, and biochemistry parameters were all comparable. SAE occurred in 0 animal in control group, 2 animals in CRS alone group including 1 animal death due to anesthesia overdose and another death due to postoperative hemorrhage, and 3 animals in CRS + HIPEC group including 1 animal death due to anesthesia overdose, and 2 animal deaths due to diarrhea 23 and 27 d after operation.

Conclusions

In this rabbit model of gastric cancer with PC, CRS alone could not bring benefit while CRS + HIPEC with docetaxel and carboplatin could significantly prolong the survival with acceptable safety.

Background

The loco-regional progression of gastric cancer usually results in peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC), characterized by the presence of tumor nodules of various size, number, and distribution on the peritoneal surface as well as malignant ascites, with very poor prognosis [1-5]. Patients with gastric PC face a dismal outcome, with a median survival of about 6 months [6].

Current treatments for such PC are systemic chemotherapy, best support care and palliative therapy. In order to tackle this problem, a new treatment modality called cytoreductive surgery (CRS) plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been developed over the past 3 decades, taking advantages of surgery to reduce visible tumor burden, and regional hyperthermic chemotherapy to eradicate micrometastases [7-10]. Although many clinical studies have been performed to test and confirm the efficacy of this combined treatment approach, there is a lack of high quality evidence from phase III randomized prospective studies. In order to more objectively evaluate such treatment, it is necessary to study this treatment modality under experimental conditions, in which most of the confounding factors could be well controlled. In this respect, suitable animal models of PC are indispensable platforms. Small animal models of PC have been established, including mouse models and rat models [11-18]. In most of these animal models, cancer cells are injected directly into the peritoneum, which will result in widespread PC in due time. Such models have been used to test various treatment modalities, including CRS and HIPEC, either alone or in combination, producing valuable information on the validity of different therapies. The small body size and delicate hemodynamic conditions are limiting factors for complex surgical interventions. Large animal models of PC might be more suitable for extensive surgical treatment. Therefore, it is necessary to establish large animal model of PC from gastric cancer for experimental studies to test extensive CRS and HIPEC.

In our previous study [19], we have established a stable rabbit model of gastric cancer with PC by injecting VX2 cancer cells into the submucosal layer of the stomach. The model is characterized by typical ulcerative gastric cancer with progressive PC, making it more suitable for surgical interventional studies to evaluate CRS and HIPEC against gastric PC.

This rabbit model of gastric cancer with PC has provided us with suitable platform to evaluate different therapeutic approaches against PC. This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CRS + HIPEC for the treatment of this large animal model of gastric PC, so as to provide support to clinical application.

Methods

Animals

Forty two male New Zealand white rabbits, body weight between 1.8-2.9 kg (Median 2.0 kg), were obtained from Animal Biosafety Level 3 Laboratory at the Animal Experimental Center of Wuhan University (Animal Study Certificate SCXK 00002826). The animals were individually housed and allowed free access to standard laboratory food and water as well as 12 h of light and dark cycle per day. The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the Center.

Construction of rabbit model of VX2 gastric carcinoma with PC

Rabbit VX2 carcinoma was used to establish gastric cancer with PC in this study. The animals were anesthetized by ear vein injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg). The abdominal skin was cleaned and disinfected. Tumor cells were injected into the stomach submucosa layer to construct rabbit models of PC as described previously [19]. Briefly, a midline incision of 3 cm long was made beginning 2 cm below the xyphoid and the upper abdomen was open. The stomach was exposed, 0.1 ml of tumor cells (5 × 1010 vial cells/L) was injected into the submucosal layer of the stomach, through the serosal layer and the muscle layer, the injection site was pressed for 1 min to keep the injected tumor cells in place, and the abdomen was closed with a double layer 3-0 vicryl interrupted suture. After tumor inoculation, Penicillin G at the dose of 100,000 IU/d was intramuscularly injected to each animal for 3 d.

Randomization and treatment

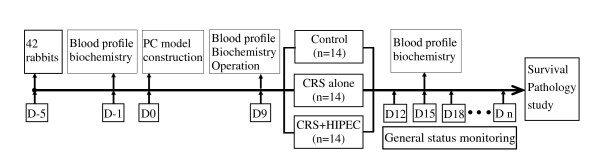

When animal model construction has been confirmed successful on day 9 after operation, these rabbits were randomized into 3 groups according to a computer generated randomize number, 14 animals in each group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study protocol. After construction of PC model of gastric cancer, 42 New Zealand white rabbits were randomized into 3 groups with 14 rabbits per group, and the effects of CRS and CRS + HIPEC were investigated. D, day; PC, peritoneal carcinomatosis; CRS, cytoreductive surgery; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

The control group was observed for natural course of disease progression without any intervention.

For CRS alone group, CRS was performed on d 9 after tumor cells inoculation. Rabbits were given 1% pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg) intravenously for anesthesia. The abdominal skin was cleaned and disinfected. The abdominal exploration was performed through a midline incision of 8 cm long beginning 1 cm below the xyphoid. Once the abdominal wall was open, detailed evaluation of the PC was conducted in different regions including the parietal peritoneum, visceral peritoneum, the omentum, stomach, liver, spleen, small intestine, colon, bladder and other pelvic tissues. Thereafter, maximal CRS was performed including a routine omentectomy, and optimal removal of tumor nodules. Unresectable tumors were cauterized. The gastric tumor itself, however, was not removed but treated by injection of absolute alcohol. After completion of CRS the abdominal wall was closed in 2 layers using 3-0 Vicryl constinuous sutures.

For CRS + HIPEC group, maximal CRS was performed on d 9 in the same fashion as in the CRS alone group, which was immediately followed by HIPEC just before the closure of abdominal cavity. Open HIPEC was performed, as this open technique was believed to provide optimal thermal homogeneity and spatial diffusion [20,21], with 250 mL of heated saline containing 10 mg of docetaxel (Wanle Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Shenzhen, China.) and 40 mg of carboplatin (Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Shandong, China.) for each animal. The abdominal cavity was rinsed twice with 250 mL of normal saline preheated to 42.0°C and perfusion tube was placed in pelvic cavity just before HIPEC. The perfusion equipment consisted of a miniature heat exchanger and a roller pump, allowing perfusion with a variable dynamic flow of 6 - 12 ml/min. An inflow catheter was inserted into the upper abdomen between the hepatic and diaphragmatic surface and an outflow catheter was placed at the pelvic floor. The perfusion solution was heated to 42.0 ± 0.5°C and infused into the peritoneal cavity at a rate of 10 ml/min through the inflow tube introduced from the automatic perfusion pump. The perfusion in the peritoneal cavity was stirred manually to make equal spatial distribution. The temperature of the perfusion solution in peritoneal space was kept at 42.0 ± 0.5°C and monitored using a thermometer on real time. The total HIPEC time was 30 min, after which the perfusion solution in the abdominal cavity was removed.

Twenty min before surgery, 100 ml of 0.9% NaCl solution with 1 g of ceftriaxone powder, 2 ml of 10% potassium chloride solution and 20 ml of 50% glucose solution was infused intravenously for rehydration, energy support and infection control in both the CRS alone group and the CRS + HIPEC group. Such treatment was continued for 3 d.

Animal observation and disease course monitoring

The general status of the animals was daily recorded in a standard form. For pathological studies, euthanasia was performed on the rabbits by overdose injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium through the ear vein. Post mortem pathological examinations included gross pathology such as tumor size and distributions; local tumor features of gastric cancer such as ulcer formation, obstruction and perforation; special features of peritoneal carcinomatosis such as bloody ascites, discrete or confluent tumor nodules on the peritoneum, omentum cake and intestinal obstructions; metastases to major organs such as the liver, adrenal glands, pancreas and the lungs.

For laboratory studies, 5 ml of blood was harvested from ear vein on the day before tumor cells inoculation as the baseline, on the day of surgery, and on d 8 after surgery. The samples were used for routine peripheral blood test, liver and kidney functions tests and biochemical tests.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) in each group, defined as the time interval form animal model construction to animal death due to any cause, including cancer progress. The secondary endpoints were body weight, biochemistry, major organ functions and serious adverse events (SAE), which was defined as severe local and/or systemic infection or death due to the procedure.

In our previous study to construct this animal model, we learned that the median survival of this gastric PC model is about 3 weeks [19]. Therefore, we calculated the sample size of this study based on this information. This trial was designed to detect at least a 30% absolute difference in OS. With a statistical power of 90% to detect such difference at 5% significance level, at least 12 animals were required in each group. Taking into consideration of unexpected events during the performance of the study, we enlarged the sample size to 14 animals in each group. Categorized variables in the two groups were compared by chi square test or Fisher's exact test. The numerical data were directly recorded, and the category data were recorded into different categories. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the survival, with log rank test. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), version 13.0 with 2-sided P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Histopathological characteristics of PC

Rabbit gastric cancer PC model was established in all animals (100%, 42/42). Nine days after tumor cells inoculation, many small, hard and transparent tumor nodules developed on the greater omentum, and typical ulcerative cancer about 0.5 cm in diameter formed on the antrum of the stomach. No ascites was observed. No obvious PC was found in other regions. There were no differences in the PC severity among three groups. This could be equivalent to clinical stage I peritoneal carcinomatosis by Gilly criteria [6].

Typical ulcerative cancer with PC was observed in post mortem pathological examinations of rabbits in control group. The stomach wall was totally invaded by the tumor to create cancer ulcer encased by confluent nodules on the greater omentum, forming a big tumor block. The abdominal wall and diaphragm were totally invaded by the tumor. Many tumor nodules formed on the intestinal wall, the mesentery and the retroperitoneum. Bloody ascites could be more than 100 ml. All the features are similar to the clinicopathologic characteristics of gastric cancer with PC in patients.

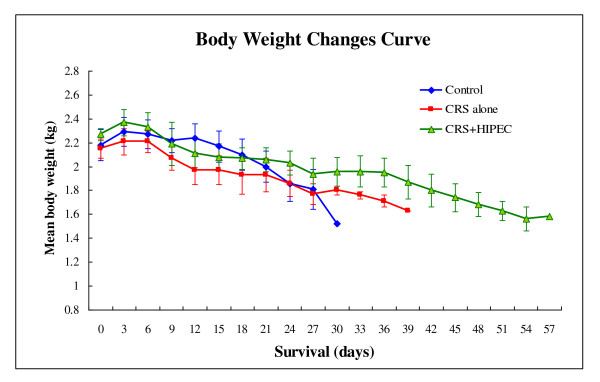

Body weight changes

The body weight of each animal was recorded every 3 d. No significant differences were found in initial body weight of 3 groups before the treatment. Perioperative body weight decreased in all groups because of the overnight fasting. In the control group, the body weight recovered once food intake was resumed but again decreased progressively till the study endpoint. In the 2 treatment groups, postoperative body weight decreased considerably during the first 3 d after surgery and then decrease became gentle along with the increased food intake in the following 5 d in 2 treatment groups. Thereafter, body weight decreased progressively again till the study endpoint in CRS alone group, while body weight could be maintained or slightly increased for the following 20 d in CRS + HIPEC group and decreased slowly till the study endpoint (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Body weight changes in 3 groups of rabbits. Compared with control and CRS groups, CRS + HIPEC group experienced slower body weight loss, although the differences among the 3 groups did not reach statistical significance.

Blood profile changes

At the baseline, on the day of surgery and on day 8 after surgery, the peripheral blood cells counts, liver and kidney function tests, and biochemistry parameters were all comparable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Blood routine tests and biochemical test results

| Range (median) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Control (n = 14) | CRS (n = 14) | CRS+HIPEC (n = 14) | P | |

| Peripheral blood tests | |||||

| A | 139~156 (149) | 129~139 (131) | 124~141 (131) | NS | |

| HGB (G/L) | B | 112~130 (128) | 102~137 (121) | 104~30 (126) | NS |

| C | 78~135 (117) | 62~123 (100) | 80~103 (92) | NS | |

| A | 6.55~7.30 (6.77) | 6.19~6.80 (6.77) | 5.98~6.48 (6.29) | NS | |

| RBC (× 109/L) | B | 5.19~6.18 (5.76) | 5.26~6.54 (5.60) | 4.87~6.37 (6.14) | NS |

| C | 4.27~6.14 (5.26) | 2.26~5.76 (5.30) | 3.97~4.70 (4.34) | NS | |

| A | 4.0~10.1 (6.5) | 7.4~9.9 (8.8) | 4.2~8.7 (4.7) | NS | |

| WBC (× 109/L) | B | 6.5~11.3 (8.0) | 4.8~10.3 (9.1) | 7.1~9.4 (9.2) | NS |

| C | 7.7~18.2 (9.2) | 3.2~8.3(4.9) | 10.0~8.3 (9.2) | NS | |

| A | 1.3~3.8 (2.7) | 2.2~5.9 (4.5) | 2.9~3.8 (3.2) | NS | |

| Neu (× 109/L) | B | 1.8~4.3 (3.8) | 1.4~8.4 (3.6) | 2.6~3.8 (3.1) | NS |

| C | 1.1~4.8 (3.0) | 0.7~4.1 (2.0) | 4.2~4.8 (4.5) | NS | |

| A | 169~385 (320) | 158~410 (267) | 94~415 (319) | NS | |

| PLT (× 109/L) | B | 68~434 (231) | 103~398 (232) | 232~682 (360) | NS |

| C | 302~663 (324) | 12~59 (27) | 36~426 (231) | NS | |

| Liver function tests | |||||

| A | 15~24 (22) | 34~44 (35) | 15~24 (22) | NS | |

| AST (U/L) | B | 28~91 (75) | 65~72 (66) | 36~8 (69) | NS |

| C | 27~30 (29) | 14~22 (20) | 15~19 (17) | NS | |

| A | 28~43 (36) | 65~72 (66) | 36~81 (69) | NS | |

| ALT (U/L) | B | 12~41 (26) | 16~38 (26) | 19~89 (29) | NS |

| C | 42~131 (50) | 54~90 (85) | 71~95 (83) | NS | |

| A | 60.7~77.0 (66.1) | 62.8~66.5 (66.0) | 58.4~66.3 (63.8) | NS | |

| TP (g/L) | B | 58 .0~69.9 (62.3) | 56.5~69.6 (62.8) | 53.2~71.5 (59.9) | NS |

| C | 61.1~65.6 (62.8) | 46.3~63.7 (55.8) | 50.2~57.8 (54.0) | NS | |

| A | 37.3~41.2 (39.6) | 36.6~41.8 (40.6) | 32.0~41.2 (39.6) | NS | |

| ALB (g/L) | B | 35.0~41.4 (37.1) | 31.3~39.8 (35.8) | 32.5~38.4 (34.9) | NS |

| C | 34.6~38.9 (36.3) | 26.4~37.4 (30.9) | 30.7~32.8 (31.8) | NS | |

| A | 23.4~35.8 (26.6) | 24.8~26.3 (25.7) | 26.4~32.6 (26.6) | NS | |

| GLB (g/L) | B | 22.2~28.5 (25.5) | 24.4~32.2 (27.3) | 19.7~33.1 (25.2) | NS |

| C | 23.9~29.3 (26.5) | 19.9~26.3 (24.9) | 19.5~25.0 (22.3) | NS | |

| A | 126~190 (159) | 127~248 (147) | 159~186 (172) | NS | |

| ALP (U/L) | B | 78~145 (98) | 45~177 (86) | 51~133 (89) | NS |

| C | 73~118 (80) | 58~114 (79) | 52~114 (83) | NS | |

| Renal function tests | |||||

| A | 6.24~15.08 (6.95) | 6.47~7.68 (7.47) | 7.28~8.44 (8.16) | NS | |

| BUN (mmol/L) | B | 8.83~14.77 (12.24) | 0.59~16.64 (10.18) | 6.82~14.94 (7.92) | NS |

| C | 5.45~6.45 (6.27) | 5.33~7.07 (6.61) | 4.83~6.45 (5.64) | NS | |

| A | 81.0~121.2 (86.5) | 80.6~99.2 (85.4) | 81.0~95.3 (83.7) | NS | |

| Cr (μmol/L) | B | 75.0~99.0 (94.9) | 70.4~107.4 (88.8) | 85.8~97.8 (91.6) | NS |

| C | 67.3~85.6 (75.7) | 60.3~69.9 (62.2) | 65.8~66.9 (66.4) | NS | |

| Electrolytes | |||||

| A | 4.10~18.97 (4.66) | 3.52~4.72 (4.21) | 3.99~10.97 (4.30) | NS | |

| K+ (mmol/L) | B | 7.34~27.13 (10.44) | 4.44~11.09 (6.29) | 4.34~12.29 (4.74) | NS |

| C | 5.14~5.91 (5.18) | 4.98~6.08 (5.14) | 5.31~6.32 (5.82) | NS | |

| A | 139.1~148.7 (145.3) | 142.8~148.8 (144.2) | 142.2~145.3 (144.7) | NS | |

| Na+ (mmol/L) | B | 124.5~146.4 (140.4) | 137.3~148.5 (141.65) | 133.6~146.4 (141.1) | NS |

| C | 133.2~138.7 (133.5) | 132.9~138.9 (135.3) | 133.8~134.3 (134.1) | NS | |

| A | 99.8~121.2 (102.6) | 101.9~107.2 (103.5) | 100.5~110.2 (102.1) | NS | |

| Cl- (mmol/L) | B | 94.6~103.9 (96.6) | 96.6~107.7 (101.1) | 97.0~106.6 (100.8) | NS |

| C | 100.0~104.1 (103.7) | 102.2~106.6 (104.7) | 103.8~104.2 (104.0) | NS | |

| A | 3.11~3.77 (3.39) | 3.05~3.18 (3.12) | 3.18~3.69 (3.63) | NS | |

| Ca++ (mmol/L) | B | 2.80~4.04 (3.70) | 3.41~3.96 (3.71) | 3.32~3.96 (3.66) | NS |

| C | 3.71~4.10 (3.80) | 3.19~3.56 (3.45) | 3.48~3.52 (3.50) | NS | |

RBC: red blood cells; WBC: white blood cells; HGB: hemoglobin; Neu: neutrophils count; PLT: platelets counts; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; A: At baseline; B: On the day of surgery; C: On d 8 after surgery; TP: total protein; ALB: albumin; GLB: globulin; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; Cr: creatinine.

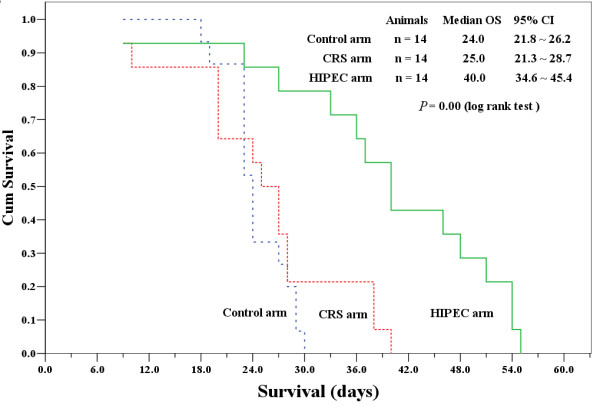

Survival

The animals in the control group did not receive any active surgical treatment, and only observed for natural history of disease progression. For animals in both CRS and CRS+HIPEC groups, complete cytoreduction was achieved either by surgical resection or cauterization for the peritoneal carcinomatosis, leaving no observable tumor nodules in the peritoneal cavity. The gastric tumor itself, however, was not removed but treated by injection of absolute alcohol. The median OS was 24.0 d (95% CI 21.8 - 26.2 d) in the control group, 25.0 d (95% CI 21.3 - 28.7 d) in CRS group, and 40.0 d (95% CI 34.6 - 45.4 d) in CRS + HIPEC group (P = 0.00, log rank test). Compared with CRS only or control group, CRS + HIPEC could extend OS by at least 15 d (60%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for control, CRS alone, and CRS + HIPEC groups. Compared with CRS only or control group, CRS + HIPEC could extend OS by at least 15 d (60%). (P = 0.00, log rank test)

Postmortem pathological examinations

Euthanasia was performed on the moribund rabbits by overdose injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium through the ear vein. Detailed information on postmortem pathological examinations was listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of post mortem pathological study in 3 groups*

| Control (n = 14) | CRS (n = 12)* | CRS+HIPEC (n = 13)§ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ulcerative gastric cancer | 100% | 100% | 100% | NA |

| Pyloric obstruction | 100% | 100% | 100% | NA |

| Gastric perforation | 28.6% | 8.3% | 8.3% | P = 0.246 |

| Greater omentum cake | 100% | removed | removed | NA |

| Liver metastases | 100% | 96.7% | 38.5% | P = 0.000 |

| Pulmonary metastases | 0.0% | 8.3% | 53.8% | P = 0.000 |

| Cancerous diaphragm | 100% | 100% | 53.8% | P = 0.000 |

| Upper abdominal wall cancer | 100% | 100% | 84.6% | P = 0.128 |

| Small intestine & mesentery seeding | 100% | 100% | 61.5% | P = 0.002 |

| Adrenal gland metastases | 100% | 100% | 23.5% | P = 0.000 |

| Kidney capsule invasion | 100% | 75.0% | 30.8% | P = 0.000 |

| Retroperitoneum metastases | 100% | 100% | 76.9% | P = 0.038 |

| Pelvic seeding | 100% | 100% | 69.2% | P = 0.009 |

| Urine retention | 57.1% | 75.0% | 61.5% | P = 0.641 |

| Bloody ascites | 100% | 100% | 38.5% | P = 0.000 |

* Two animals were excluded in CRS group, including 1 death due to anesthesia overdose on d 9 and another death due to postoperative hemorrhage on d 10.

§ One animal in CRS+HIPEC group was excluded due to anesthesia overdose death on d 9.

NA: not applicable.

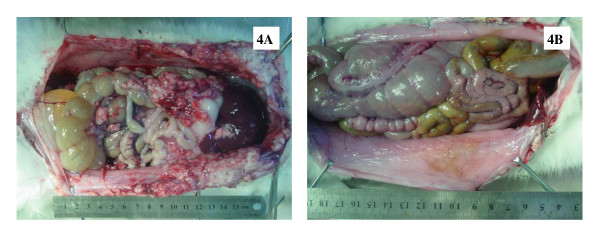

Severe Adverse Events

SAE occurred in 0 animal in control group, 2 animals in CRS alone group including 1 death due to anesthesia overdose (OS = 9 d) and another death due to postoperative hemorrhage (OS = 10 d), and 3 animals in CRS + HIPEC group including 1 death due to anesthesia overdose (OS = 9 d), and 2 deaths due to diarrhea 23 and 27 d after operation. A direct comparison in gross pathology on d 27 of a rabbit in CRS group (Figure 4A) and a rabbit in CRS + HIPEC group (Figure 4B) showed significant differences in PC severity.

Figure 4.

On day 27, post mortem pathological examinations of a rabbit in CRS group (2A) and a rabbit in CRS + HIPEC group (2B). In CRS group, widespread PC recurrence was evident even after sytoreductive surgery. In the CRS + HIPEC group, hyperthermic chemoperfusion significantly retarded PC recurrence.

Discussion

This study has provided new evidence to support CRS + HIPEC to treat gastric PC. Compared with control group and CRS alone group, the CRS + HIPEC group could have an additional survival gain of at least 15 d (60%). In addition to such significant survival benefit, other improvements have also been observed, including body weight, PC severities, ascites, liver and kidney functions, and blood electrolytes.

This study also suggests that in established gastric PC, simply performing CRS may not bring survival benefit. The animals in the CRS group had a median survival of 25 d, which is not statistically different from 24 d in the control group.

PC has been increasingly recognized as an important clinical problem and increasing efforts have been devoted to investigating the mechanism and coping strategies against this disease. Clinical trials in selected gastric or colorectal PC patients have provided evidence in favor of CRS + HIPEC for these patients, and the only phase III prospective randomized trial in colorectal PC patients reported a median survival advantage of 70% gain in overall survival (22.4 months in the CRS + HIPEC group VS 12.6 months with standard palliative care alone) [22]. The encouraging results by Yonemura [8] and Glehen [9] in gastric PC provided more compelling evidence to support this combined treatment modality. Nevertheless, controversies regarding the usefulness and value of such approach remain [23,24]. It seems unlikely that this issue will be resolved shortly in randomized clinical trials. Therefore, it is necessary to study the treatment modality under experimental conditions, in which most of the confounding factors could be well controlled for more objective evaluation of HIPEC.

In recent years, increasing number of animal models of PC have been intensively studied, including nude mouse model of gastric cancer PC constructed by implanting human gastric cancer cells [25-28]; mouse colon cancer PC model constructed by injecting colon cancer cells into the abdominal cavity of Balb/C mice [29]; rat colon carcinoma PC models constructed through injecting CC531 colon carcinoma cells into the abdominal cavity of Wag/Rij rats [15,30-33] or injecting syngeneic colon adenocarcinoma cells (DHD/K12/TRb) into the abdominal cavity of athymic BD IX/HansHsd rats [14,18,34,35]; murine xenograft PC model of appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma constructed by implanting human appendiceal neoplasms into the peritoneal cavity of homozygous nude mice [36]; mouse ovarian cancer PC model constructed through injecting human serous or epithelial ovarian cancer cells into the abdominal cavity of mice [37-39] or injecting murine ovarian surface epithelial cells (ID8 cells) under ovarian bursa of C57BL6 mice [39].

Compared with the small animal PC models, our rabbit model of gastric PC is the first large animal PC model, more suitable for complex surgical interventional studies such as CRS + HIPEC. In addition, this model reproduces the whole pathological process from the primary gastric cancer to the development of PC, resembling the complete clinico-pathological features of human gastric PC.

To our knowledge, there have been 3 reports in the literature on the efficacy of CRS + HIPEC in experimental animal models of PC. Klaver et al [34] used the rat colonic carcinoma PC model to test whether the addition of HIPEC to CRS is essential for survival benefit. The rats were randomized into 3 treatment groups of 20 rats each, CRS alone, CRS + HIPEC (mitomycin 15 mg/m2 at 42.0°C for 90 min) and CRS + HIPEC (mitomycin C 35 mg/m2 at 42.0°C for 90 min). The CRS + HIPEC achieved a significant survival gain of over 120% (the median survival of 43, 75 and 97 d, P < 0.01). Pelz et al [15] used similar rat colonic carcinoma PC model to investigate HIPEC. After 10 d of tumor cells inoculation, the rats were randomized into 3 groups of 6 animals each, control, HIPEC (mitomycin C 15 mg/m2 at 40.5 - 41.5°C for 90 min), and normathermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (mitomycin C 10 mg/m2 i.p.). Although the study did not report the overall survival, the HIPEC group did have significantly smaller tumor weight, fewer tumor nodules, decreased cancer index and better clinical complete response rate, compared with control or normathermic ip mitomycin treatment alone. In a similar study on rat colon cancer PC model, Raue et al [36] found that only CRS + HIPEC with MMC 15 mg/m2 at 41.2 - 42.3°C for 60 min could result in significant reduction in tumor weigh and PC index. Again this study did not report on the overall survival.

Conclusions

In summary, this study on the first large animal model of gastric PC has proved that CRS + HIPEC could indeed bring survival benefit with acceptable safety, providing evidence to support this combined strategy to treat selected patients of gastric cancer with PC.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YLI conceived, designed and partly conducted the study. LT, LJM, CQH and XJY conducted the study and drafted the manuscript. YFZ and YY provided technical support. All authors have read the approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Li Tang, Email: tangli_whu@163.com.

Lie-Jun Mei, Email: mlj-1971@163.com.

Xiao-Jun Yang, Email: totti800105@yahoo.com.cn.

Chao-Qun Huang, Email: hcq820228@126.com.

Yun-Feng Zhou, Email: yunfeng_zhou@hotmail.com.

Yutaka Yonemura, Email: y.yonemura@coda.ocn.ne.jp.

Yan Li, Email: liyansd2@163.com.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the grants supporting New Strategies to Treat Peritoneal Carcinomatosis from Hubei Sciences and Technology Bureau (2008BCC011, 2060402-542), the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 20621502, 20921062), and the National University Student Innovation Training Project of China (081048646).

References

- Blair SL, Chu DZ, Schwarz RE. Outcome of palliative operations for malignant bowel obstruction in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from nongynecological cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:632–637. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammaa HAH, Li Y, Yonemura Y. Current status and future strategies of cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal hyperthemic for peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1159–1166. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fizazi K, Doubre H, Le Chevalier T, Riviere A, Viala J, Daniel C, Robert L, Barthélemy P, Fandi A, Ruffié P. Combination of raltitrexed and oxaliplatin is an active regimen in malignant mesothelioma: Results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:349–354. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Portilla A, Cendoya I, López de Tejada I, Olabarria I, Martínez de Lecea C, Magrach L, Gil A, Echebarría J, Valdovinos M, Larrabide I. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Current treatment. Review and update. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:716–737. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082005001000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonemura Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Ito H, Endo Y, Miura M, Kiyosaki K, Sasaki T. Cytoreduction and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for carcinomatosis from gastric cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;134:357–373. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-48993-3_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, Fontaumard E, Brachet A, Caillot JL, Faure JL, Porcheron J, Peix JL, Francois Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000;88:358–363. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<358::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ, Li Y, al-shammaa HAH, Yang GL, Liu SP, Lu YL, Zhang JW, Yonemura Y. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival in selected patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from abdominal and pelvic malignancies: results of 21 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:345–351. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonemura Y, Kawamura T, Bandou E, Takahashi S, Sawa T, Matsuki. Treatment of peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer by peritonectomy and chemohyperthermic peritoneal perfusion. Br J Surg. 2005;92:370–375. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glehen O, Schreiber V, Cotte E, Sayag-Beaujard AC, Osinsky D, Freyer G, Francois Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2004;139:20–26. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Fujiwara Y, Sugita Y, Azama T, Ishii T, Taniguchi K, Yamazaki K, Takiguchi S, Yasuda T, Yano M, Monden M. Application of molecular diagnosis for detection of peritoneal micrometastasis and evaluation of preoperative chemotherapy in advanced gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:14–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02524340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatmark K, Reed W, Halvorsen T, Sørensen O, Wiig JN, Larsen SG, Fodstad Ø, Giercksky KE. Pseudomyxoma peritonei--two novel orthotopic mouse models portray the PMCA-I histopathologic subtype. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braumann C, Jacobi CA, Rogalla S, Menenakos C, Fuehrer K, Trefzer U, Hofmann M. The tumor suppressive reagent taurolidine inhibits growth of malignant melanoma - a mouse model. J Surg Res. 2007;143:327–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelz JOW, Doerfer J, Decker M, Dimmler A, Hohenberger W, Meyer T. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (HIPEC) decrease wound strength of colonic anastomosis in a rat model. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:941–947. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0246-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto J, Jansen PL, Lucas S, Schumpelick V, Jansen M. Reduction of peritoneal carcinomatosis by intraperitoneal administration of phospholipids in rats. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelz JOW, Doerfer J, Dimmler A, Hohenberger W, Meyer T. Histological response of peritoneal carcinomatosis after hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (HIPEC) in experimental investigations. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelz JOW, Doerfer J, Hohenberger W, Meyer T. A new survival model for hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in tumor-bearing rats in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braumann C, Stuhldreier B, Bobrich E, Menenakos C, Rogalla S, Jacobi CA. High doses of taurolidine inhibit advanced intraperitoneal tumor growth in rats. J Surg Res. 2005;129:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monneuse O, Mestrallet JP, Quash G, Gilly FN, Glehen O. Intraperitoneal treatment with dimethylthioampal DIMATE combined with surgical debulking is effective for experimental peritoneal carcinomatosis in a rat model. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:769–774. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei LJ, Yang XJ, Tang L, al-shammaa HAH, Yonemura Y, Li Y. Establishment and identification of a rabbit model of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ, Li Y, Yonemura Y. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthemic intraperitoneal chemotherapy to treat gastric cancer with ascites and/or peritoneal carcinomatosis: results from a Chinese center. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:457–464. doi: 10.1002/jso.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JH IV, Shen P, Levine EA. Intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: Current status and future directions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:765–777. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Slooten GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FAN. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin OncoL. 2003;21:3737–3743. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri VP. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: a panacea or just an obstacle course for the patient? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias D, Delperro JR, Sideris L, Benhamou E, Pocard M, Baton O, Giovannini M, Lasser P. Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: impact of complete cytoreductive surgery and difficulties in conducting randomized trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:518–521. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen M, Treutner KH, Jansen PL, Zuber S, Otto J, Tietze L, Schumpelick V. Inhibition of gastric cancer cell adhesion in nude mice by inraperitoneal phospholipids. World J Surg. 2005;29:708–714. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchhorn HM, Seidl C, Beck R, Saur D, Apostolidis C, Morgenstern A, Schwaiger M, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R. Non-invasive visualisation of the development of peritoneal carcinomatosis and tumour regression after 213Bi-radioimmunotherapy using bioluminescence imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:841–849. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piso P, Aselmann H, von Wasielewski R, Dahlke MH, Klempnauer J, Schlitt HJ. Prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis from human gastric cancer cells by adjuvant-type intraperitoneal immunotherapy in a SCID mouse model. Eur Surg Res. 2003;35:470–476. doi: 10.1159/000073385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty MF, Takeda A, Stoeltzing O, Liu W, Fan F, Reinmuth N, Akagi M, Bucana C, Mansfield PF, Ryan A, Ellis LM. ZD6126 inhibits orthotopic growth and peritoneal carcinomatosis in a mouse model of human gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:705–711. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulu Y, Dorfman JD, Kuruppu D, Fuchs BC, Goodwin JM, Fujii T, Kuroda T, Lanuti M, Tanabe KK. Comparison of intravenous versus intraperitoneal administration of oncolytic herpes simplex virus 1 for peritoneal carcinomatosis in mice. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:291–297. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hribaschek A, Kuhn R, Pross M, Meyer F, Fahlke J, Ridwelski K, Boltze C, Lippert H. Intraperitoneal versus intravenous CPT-11 given intra- and postoperatively for peritoneal carcinomatosis in a rat model. Surg Today. 2006;36:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-3096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarts F, Koppe MJ, Hendriks T, vanEerd JEM, Oyen WJG, Boerman OC, Bleichrodt RP. Timing of Adjuvant Radioimmunotherapy after Cytoreductive Surgery in Experimental Peritoneal Carcinomatosis of Colorectal Origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;14:533–540. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarts F, Bleichrodt RP, de Man B, Lomme R, Boerman OC, Hendriks T. The effects of adjuvant experimental radioimmunotherapy and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy on intestinal and abdominal healing after cytoreductive surgery for peritoneal carcinomatosis in the rat. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3299–3307. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver YLB, Hendriks T, Lomme RMLM, Rutten HJT, Bleichrodt RP, de Hingh IHJT. Introperative hyperthemic intraperitoneal chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery for pertitoneal carcinomatosis in an experimental model. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1874–1880. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann J, Kilian M, Atanassov V, Braumann C, Ordemann J, Jacobi CA. First surgical tumour reduction of peritoneal surface malignancy in a rat's model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:445–449. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue W, Kilian M, Braumann C, Atanassow V, Makareinis A, Caldenas S, Schwenk W, Hartmann J. Multmodel approach for treatment of peritoneal surface malignancises in a tumer-bearing rat model. Int J Colorectol Dis. 2010;25:245–250. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0819-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavanur AA, Parimi V, Malley MO, Nikiforova M, Bartlett DL, Davison JM. Establishment and characterization of a murine xenograft model of appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Int J Exp Path. 2010;91:357–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei BR, Hoover SB, Ross MM, Zhou WD, Meani F, Edwards JB, Spehalski EI, Risinger JI, Alvord WG, Quiñones OA, Belluco C, Martella L, Campagnutta E, Ravaggi A, Dai RM, Goldsmith PK, Woolard KD, Pecorelli S, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF, Simpson RM. Serum S100A6 concentration predicts peritoneal tumor burden in mice with epithelial ovarian cancer and is associated with advanced stage in patients. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth RA, Upadhyay R, Stangenberg L, Sheth R, Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Improved detection of ovarian cancer metastases by intraoperative quantitative fluorescence protease imaging in a pre-clinical modal. Gyn Oncol. 2009;112:616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway J, Moorehead R, Shaw P, Petrik J. Epithelial-stromal interaction increases cell proliferation, survival and tumorigenicity in a mouse model of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Gyn Oncol. 2008;108:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]