Abstract

The paradental cyst is commonly misinterpreted when associated with atypical clinical and radiographic characteristics, in turn causing diagnostic problems. For this reason, the study of the differential diagnosis of this lesion has become extremely important. In addition, the correlation of clinical, histologic, and radiographic findings are also of great value in obtaining accurate diagnoses. The minor variations in the clinical appearance of paradental cysts make it feasible to consider the two main groups of cysts separately: those associated with 1st and 2nd permanent molars of the mandible and those associated with the 3rd mandibular molar. Moreover, this distinction in localization may well dictate the necessary treatment. Bearing in mind the minor clinical variations, the present article aims to discuss the differential diagnosis of this lesion and its different possible treatments by presenting a case report to illustrate the findings.

Keywords: Jaw cysts, Odontogenic cysts, Paradental cyst

Introduction

In 1930, Hofrath [1] became the first author to report on several cases of jaw cysts located distally to 3rd mandibular molar with pericoronitis. Analyzing the clinical, radiological, and histological features of these cysts described by Hofrath, it can be said that all these lesions fit the present-day definition of paradental cysts (PC) [2], a term first introduced by Craig [3] in 1976.

Some hypotheses have been raised concerning the etiology of PCs. A wide range of authors believe that the reduced enamel epithelium and epithelial Malassez rests are keys to the formation of PCs [2–5]. It is believed that these epithelial remnants in response to inflammatory stimuli may potentially proliferate, thus giving rise to several different odontogenic cysts, including the PC. However, Ackermann et al. [6] argued that if the Malassez remnants were responsible for this development, then the PCs should be equally distributed around the root surface. Other hypotheses include an origin from the crevicular epithelium and epithelial remnants of the dental lamina [2].

Colgan et al. [7] believe that the resultant inflammatory process of food impaction in the soft tissues leads to the occlusion of the opening of a pericoronal pocket. Fluid accumulates within this obstructed pocket by osmotic processes as a consequence of the inflammation, in turn leading to cystic expansion.

The presence of a small projection of enamel within the bifurcation area of the roots on the buccal aspect of the teeth has been mentioned by several authors as part of the etiology of PCs [3, 4, 6, 8]. Enamel pearls can predispose the area to accumulation of bacterial dental plaque, facilitating the progression of periodontal breakdown and local bone destruction [9], subsequently triggering the development of a cyst [3, 4]. Fowler and Brannon [4] extended Craig’s [3] concept to suggest that the obstruction of the pocket formed by the pericoronitis would likely result in the formation of a cyst.

The major clinical feature of the PC is the presence of a recurring inflammatory periodontal process, usually pericoronitis. This cyst presents only a few signs and mild symptoms, including discomfort, tenderness, moderate pain, and, in some cases, suppuration through the periodontal sulcus [2, 10, 11]. Asymptomatic cases can occur and are diagnosed on a case by case basis by means of radiography [12], whereas others remain undetected [3] due to the radiographic superimposition of other anatomical structures.

PCs commonly appear on buccal aspects [13–15] and rarely on the mesial aspect [2, 6] of partially or fully erupted vital teeth. An explanation as to why the buccal aspect of a permanent mandibular is so often the site of PC development was offered [10]: the mesio-buccal cusp is the first to break through the oral mucosa and be exposed to the oral environment. Other local anatomical factors (crown form, fissure pattern, adjacent teeth, and gingival architecture) may also influence the precise location of the cyst [7].

PC is commonly associated with third mandibular molars [2–4, 6–8, 11, 13, 14, 16] and may also occur, although less frequently, with the second [14, 17] and first molars [16, 18–21]. There are rare reports associating PC with premolars [15] or incisors/canines [22]. Only a few cases of PC [8, 12, 22, 23] have been reported in maxillary teeth. According to Philipsen et al. [2], 61.4% of the 342 cases reviewed in their study were associated with the 3rd mandibular molar, while 35.9% were found to be associated with either the 1st or 2nd mandibular permanent molars. Recognition of its restricted distribution may increase the awareness of the PC [7]. Moreover, of 109 cases of PC in 1st or 2nd mandibular molars reviewed by Philipsen et al. [2], 26 cases (23.9%) occurred bilaterally. Therefore, it is recommended that the contralateral tooth be carefully evaluated for a second lesion.

There are some factors (superimposition of anatomical structures, presence of infection, and lesion size and location) that can vary the radiographic presentation of the PC [11]. However, the lesion frequently produces a well-defined radiolucency, mimicking the periapical pathology of the involved tooth [3, 4, 24] or semilunar-shaped bony resorption on the distal aspect [6]. As the inflammatory component is not of endodontic origin, the periodontal ligament space and the lamina dura are intact and continuous around the root [2]. A periosteal reaction (single or multilayered/laminated deposition of new bone) is common, resulting in one or several parallel opaque layers [2].

Bearing in mind the minor clinical variations, the present article aims to discuss the differential diagnosis of this lesion and its different possible treatments by presenting a case report to illustrate the findings.

Case Report

A 6-year-old female Caucasian patient was referred by her dentist to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, with the main complaint of “swelling in the jaw on the right side” for the past 2 months. The patient was asymptomatic, reported no paresthesia or abnormal sensitivity, and showed no suppuration in the affected site. The mucosa appeared to be normal, and the first permanent molar had partially erupted. By palpation, a hardened increase in volume could be observed in the mandibular body region, next to tooth 30. Carious lesions could be identified in primary teeth E and D.

Panoramic, occlusal, and periapical radiographs were requested. An expansion similar to an onion skin (multilayered-laminated deposition of new bone) of the vestibular cortical bone could be observed in the region of tooth 30 (Fig. 1), possibly due to a periosteal reaction. A radiolucency related to this tooth was also apparent.

Fig. 1.

Expansion of the vestibular cortical bone

Due to the clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis of either periostitis ossificans or PC was suspected. Pulp vitality tests were performed in all the posterior elements on the left side. Given the positive response found in all teeth tested, the suspicion of infection (periostitis ossificans) was ruled out. Due to the presence of radiolucency in the distal follicular space of tooth 30, which appeared in the panoramic radiograph (Fig. 2), a dentigerous cyst was also suspected.

Fig. 2.

Presence of radiolucency in the distal follicular space of the first permanent molar

A computed tomography (CT) scan was then requested. A hypodense area could be observed in the cervical vestibular region of tooth 30 in both the coronal CT (Fig. 3) and the axial CT (Fig. 4a), which was suggestive of a cystic lesion. A hyperdense area associated with the hypodense area, expanding into the cortical vestibular region of the lower edge of the right mandibular body, could also be identified, suggesting a periosteal reaction (Fig. 4b). The periodontal ligament space and the lamina dura were intact and continuous around the root (Fig. 4c). An inferior view of the mandible in a three-dimensional CT (Fig. 5) clearly showed expansion of the vestibular bone.

Fig. 3.

Coronal CT. Hypodense area in the vestibular region of the molar

Fig. 4.

Axial CT. a Hypodense area in the vestibular region of molar; b expansion of the vestibular cortical bone; c periodontal ligament space and the lamina dura were intact and continuous around the root

Fig. 5.

Three-dimensional CT. Expansion of the vestibular bone

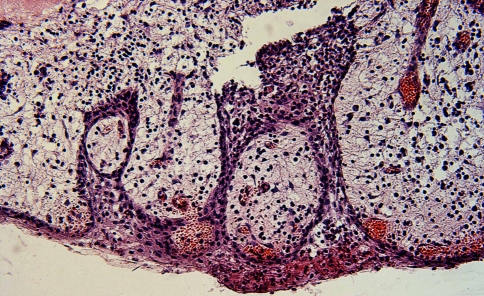

Fine needle aspiration revealed bloody fluid. Enucleation of the lesion was performed under local anesthesia in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. On macroscopic examination, irregular, soft, white tissue with reddish areas measuring 10 × 9 × 4 mm was observed. Microscopic examination (Fig. 6) revealed a cystic capsule with non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, showing hyperplasia and leukocyte exocytosis. The capsule consisted of fibrous connective tissue presenting hyperemic vessels, areas of hemorrhage, and inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates. The findings were compatible with the diagnosis of inflammatory paradental cyst.

Fig. 6.

Histologic exam (HE, 400x). Non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, showing hyperplasia. Connective tissue presenting hyperemic vessels, areas of hemorrhage, and inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates

The patient has been undergoing post-operative follow-up for 16 months. A mandibular occlusal film showed the resolution of the proliferative bone. The eruption of the right mandibular first permanent molar with healthy periodontium occurred normally.

Discussion

The prevalence of PC varies from 1% to 5% in all odontogenic cysts [3, 6, 25]. This fact justifies its inclusion in the group of rare lesions [15]. However, it is believed that the PC has been misdiagnosed as dentigerous cyst, lateral radicular cyst, pericoronitis, or some other entity related to the inflammatory conditions of the dental follicle [26]. The variety of names for the same entity may also have added to this misunderstanding: inflammatory collateral cyst [22], mandibular infected buccal cyst [27], mandibular buccal bifurcation cyst [10, 28], inflammatory lateral periodontal cyst [29], and inflammatory PC [2, 8]. Moreover, two other facts may well have resulted in the misdiagnosis of PC [5]: the fact that histopathologic analyses of extirpated follicular sacs are rarely performed and the relatively recent characterization of the cyst. For this reason, the study of the differential diagnosis of this lesion has become extremely important.

A periodontal pocket (a), periostitis ossificans (b), dentigerous cyst (c), and lateral radicular cyst (d) can be considered as differential diagnoses, depending on radiographic and clinical findings [2, 11, 24, 30–32].

A PC mimicking a periodontal pocket (a) was recently reported in the literature [32]. Periodontal abscesses commonly develop due to chronic periodontitis. Likewise, a localized periodontal pocket of deep probing should not develop into a healthy, freshly erupted, permanent molar [32], especially in a 6-year-old child, which was not the case here.

Periostitis ossificans (b) was reported in the literature as a differential diagnosis of PC [30], where the clinical, radiographic, and microscopic features suggested that osteomyelitis originated from mandibular molars. Within this condition, radiologic findings by panoramic, occlusal, dental, and intraoral radiographs reveal a peripheral dense sclerotic bone with occasional ill-defined areas of osteolysis within the lesion [33]. The deposition of new bone adopts a concentric growth pattern involving the cortical mandibular edge and has an “onion skin” appearance with trabeculae perpendicular to these layers [34]. Considering that the periostitis ossificans of the mandible is commonly related to carious dentitions or previous dental extractions which occur in close proximity to the bony lesion [33], this diagnosis was excluded, given the positive response in pulp vitality tests found in all teeth tested and the absence of previous extraction in the region.

The preservation of the distal follicular space in a radiograph [3] is a useful diagnostic feature to distinguish PCs from dentigerous cysts (c). It indicates that most of the follicle is not involved in the process of cyst development [7]. This may have led to an initial diagnosis of dentigerous cyst in the case report, but it was ruled out due to histopathological results. In contrast to the PC, an epithelium consisting of two to four layers of cuboidal epithelial cells with a flat epithelial-connective tissue interface is generally present in dentigerous cysts. However, in the presence of inflammation, hyperplasia and leukocyte exocytosis, similar to that observed in PCs, can be observed. The epithelium is most frequently found adhering to the cemento-enamel junction. In addition, the bony cavitation of a lateral dentigerous cyst is commonly found around the entire crown of an unerupted tooth [5]. Thus, the diagnosis of a dentigerous cyst in the present case was ruled out through a combination of histopathologic results and radiographic features demonstrated by CT.

The PC has the same histopathologic features of other odontogenic cysts of inflammatory origin [3, 15, 24]: a connective tissue capsule with heavy inflammatory infiltrate, a hyperplastic non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium [2–4, 6, 8, 11, 15, 31], and the eventual presence of foci of hemosiderin pigment and cholesterol clefts [2, 3, 6, 8, 15]. If the vitality test suggests a non-vital pulp, which was not the case here, the diagnosis of a lateral radicular cyst (d), rather than a PC, should be considered. The pulp vitality test is a key factor in the differential diagnosis among these lesions, given that they present the same histopathologic features [5]. If the PC presents variable clinical and radiographic signs [3], and is being histologically confounded with radicular cysts, a correlation of all clinical, radiographic, and histologic data to obtain a definitive diagnosis is essential. Some surgical findings (bony cavitation, cystic content, and location of lesion adherence) may also be helpful [5].

In the current case, the involvement of a mandibular molar, the buccal bony cavitation, the periosteal reaction, and the positive response in vitality tests suggested a PC, whcih was confirmed by histologic analysis. The only typical clinical finding of PC which was not present was the partial eruption of the tooth.

Three lesions present with the same etiology and histologic features: the inflammatory collateral cyst, the PC, and the mandibular infected buccal cyst. Differences in the clinical and radiologic presentation of these lesions may well be related to the different teeth involved and the difference in the ages at which these teeth erupt [28, 35]. So close are the similarities with PC that the lesions are considered by some to be the same entity, regardless of localization [2, 10, 35]. Although even today controversy on this issue still exists, the present study supports the opinion of some authors [2, 28] that the minor variations in clinical appearance make it feasible to consider the two main groups of cysts separately: those associated with 1st and 2nd permanent molars of the mandible and those associated with the 3rd mandibular molar. Moreover, this distinction in localization may well dictate the necessary treatment.

Surgical removal of the tooth and the PC has been considered the treatment of choice when the involved tooth is a third molar [2, 8, 11]. Enucleation of the lesion with the maintenance of the associated tooth, as occurred in the present case, can be recommended when the first or second molars are involved [2, 11, 17–19], in an attempt to preserve the important permanent teeth in the mandibular arch. Complete removal is advocated although to date, recurrences have not been reported [4, 8, 15, 28, 31].

Some authors claim that the growth of the PC is self-limiting [31] because large lesions have yet to be found. There is also the possibility of spontaneous drainage, leading to the regression of the lesion [21, 31] by depressurization and spontaneous healing. The present study supports the findings from the previous authors [18, 28, 31] that the tooth associated with this cyst can be saved in nearly all cases, as occurred in the present case.

Conclusions

Association with mandibular molars seems to be a characteristic clinical feature of the PC and recognition of its restricted distribution may increase awareness of this lesion. Correlating the surgical, radiographic, and histologic findings is required to obtain a final diagnosis of PC. Surgical removal of the tooth and the PC has been considered the treatment of choice when the involved tooth is a third molar. Enucleation of the lesion with the maintenance of the associated tooth can be recommended when the first or second molars are involved, in an attempt to preserve important permanent teeth in the mandibular arch.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Martinho Campolina Rebello Horta, Dr. Mário Sérgio Fonseca, and Dr. Paulo Eduardo Alencar Souza.

Contributor Information

Bruno Ramos Chrcanovic, Phone: +55-31-91625090, FAX: +55-31-32920997, Email: brunochrcanovic@hotmail.com.

Brenda Mayra Maciel Vasconcelos Reis, Phone: +55-31-87930678, FAX: +55-31-35413452, Email: brendamayra19@hotmail.com.

Belini Freire-Maia, Phone: +55-31-99843817, FAX: +55-31-32813817, Email: belinimaia@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hofrath H. Über das Vorkommen von Talgdrüsen in der Wandung einer Zahncyste, zugleich ein Beitrag zur Pathogenese der Kiefer-Zahncysten. Deutsche Monatsschr Zahnheilk. 1930;48:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Ogawa I, et al. The inflammatory paradental cyst: a critical review of 342 cases from a literature survey, including 17 new cases from the author’s files. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig GT. The paradental cyst: a specific inflammatory odontogenic cyst. Br Dent J. 1976;141:9–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4803781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler CB, Brannon RB. The paradental cyst: a clinicopathologic study of six new cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanno CM, Gulinelli JL, Nagata MJ, et al. Paradental cyst: report of two cases. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1602–1606. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackermann G, Cohen M, Altini M. The paradental cyst: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:308–312. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colgan CM, Henry J, Napier SS, et al. Paradental cysts: a role for food impaction in the pathogenesis? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:162–168. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vedtofte P, Praetorius F. The inflammatory paradental cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:182–188. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrcanovic BR, Abreu MHNG, Custódio ALN. Prevalence of enamel pearls in teeth from a human teeth bank. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:257–260. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoneman DW, Worth HM. The mandibular infected buccal cyst: molar area. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1983;56:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bsoul SA, Flint DJ, Terezhalmy GT, et al. Paradental cyst (inflammatory collateral, mandibular infected buccal cyst) Quintessence Int. 2002;33:782–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vedtofte P, Holmstrup P. Inflammatory paradental cysts in the globulomaxillary region. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989;18:125–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souza SOM, Corrêa L, Deboni MC, et al. Clinicopathologic features of 54 cases of paradental cyst. Quintessence Int. 2001;32:737–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim AA-T, Peck RH-L. Bilateral mandibular cyst: lateral radicular cyst, paradental cyst, or mandibular infected buccal cyst? Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:825–827. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morimoto Y, Tanaka T, Nishida I, et al. Inflammatory paradental cyst (IPC) in the mandibular premolar region in children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el-Magboul K, Duggal MS, Pedlar J. Mandibular infected buccal cyst or a paradental cyst? Report of case. Br Dent J. 1993;175:330–332. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Conde R, Aguirre JM, Pindborg JJ. Paradental cyst of the second molar: report of a bilateral case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:1212–1214. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90638-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camarda AJ, Pham J, Forest D. Mandibular infected buccal cyst: report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:528–534. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Packota GV, Hall JM, Lanigan DT, et al. Paradental cysts on mandibular first molars in children: report of five cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1990;19:126–132. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.19.3.2088785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohay RN, Weinberg S, Thorner PS. The paradental cyst of the mandibular permanent first molar: report of a bilateral case. ASDC J Dent Child. 1992;59:361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez RS, Oliveira JR, Castro WH. Spontaneous regression of a paradental cyst. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2001;30:296. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Main DM. Epithelial jaw cysts: a clinicopathological reappraisal. Br J Oral Surg. 1970;8:114–125. doi: 10.1016/S0007-117X(70)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohmori K, Murase H, Kubota M, et al. A case of inflammatory paradental cyst of maxillary incisor (in Japanese). Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;38:2087.

- 24.Silva TA, Batista AC, Camarini ET, et al. Paradental cyst mimicking a radicular cyst on the adjacent tooth: case report and review of terminology. J Endod. 2003;29:73–76. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200301000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreidler J, Raubenheimer EJ, Heerden WFP. A retrospective analysis of 367 cystic lesions of the jaw: the Ulm experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21:339–341. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindh C, Larsson Å. Unusual jaw-bone cysts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:258–263. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90390-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallego L, Baladrón J, Junquera L. Bilateral mandibular infected buccal cyst: a new image. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1650–1654. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pompura JR, Sándor GKB, Stoneman DW. The buccal bifurcation cyst: a prospective study of treatment outcomes in 44 sites. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:215–221. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Main DM. Epithelial jaw cysts: 10 years of the WHO classification. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf J, Hietanen J. The mandibular infected buccal cyst (paradental cyst). A radiographic and histological study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;28:322–325. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(90)90107-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David LA, Sándor GKB, Stoneman DW. The buccal bifurcation cyst: is non-surgical treatment an option? J Can Dent Assoc. 1998;64:712–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelka M, Waes H. Paradental cyst mimicking a periodontal pocket: case report of a conservative treatment approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:514–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felsberg GJ, Gore RL, Scwetzer ME, et al. Sclerosing osteomyelitis of Garré (periostitis ossificans) Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90188-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beli E, Matteini C, Andreano T. Sclerosing osteomyelitis of Garré periostitis ossificans. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:765–768. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson IO, Waal J, Nortje CJ. Mandibular infected buccal cyst and paradental cyst: the same or separate entities? J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1997;52:503–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]