Abstract

AIM: To identify pancreatographic findings that facilitate differentiating between autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) and pancreatic cancer (PC) on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

METHODS: ERCP findings of 48 AIP and 143 PC patients were compared. Diagnostic accuracies for AIP by ERCP and MRCP were compared in 30 AIP patients.

RESULTS: The following ERCP findings suggested a diagnosis of AIP rather than PC. Obstruction of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) was more frequently detected in PC (P < 0.001). Skipped MPD lesions were detected only in AIP (P < 0.001). Side branch derivation from the narrowed MPD was more frequent in AIP (P < 0.001). The narrowed MPD was longer in AIP (P < 0.001), and a narrowed MPD longer than 3 cm was more frequent in AIP (P < 0.001). Maximal diameter of the upstream MPD was smaller in AIP (P < 0.001), and upstream dilatation of the MPD less than 5 mm was more frequent in AIP (P < 0.001). Stenosis of the lower bile duct was smooth in 87% of AIP and irregular in 65% of PC patients (P < 0.001). Stenosis of the intrahepatic or hilar bile duct was detected only in AIP (P = 0.001). On MRCP, diffuse narrowing of the MPD on ERCP was shown as a skipped non-visualized lesion in 50% and faint visualization in 19%, but segmental narrowing of the MPD was visualized faintly in only 14%.

CONCLUSION: Several ERCP findings are useful for differentiating AIP from PC. Although MRCP cannot replace ERCP for the diagnostic evaluation of AIP, some MRCP findings support the diagnosis of AIP.

Keywords: Autoimmune pancreatitis, Pancreatic cancer, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a newly described entity of pancreatitis, the pathogenesis of which appears to involve autoimmune mechanisms[1-4]. Clinically, AIP patients and patients with pancreatic cancer (PC) share many features, such as preponderance of elderly males, frequent initial symptom of painless jaundice, development of new-onset diabetes mellitus, and elevated levels of serum tumor markers. Radiologically, focal swelling of the pancreas, the “double-duct sign”, representing strictures in both biliary and pancreatic ducts, and encasement of peripancreatic arteries and portal veins are sometimes detected in both AIP and PC[4-6]. AIP often mimics PC, and 2.4% of 1808 pancreatic resections in the USA were reported to have AIP on histological examination[7]. AIP responds dramatically to steroid therapy; therefore, accurate diagnosis of AIP can avoid unnecessary laparotomy or pancreatic resection.

Serum IgG4 levels were elevated in 77%[8]-81%[9] of AIP patients, but they were also elevated in 4%[8]-10%[10] of PC patients. There is no definite serological marker for AIP; therefore, AIP is currently diagnosed using a combination of characteristic radiological, serological, and pathological findings. Irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a characteristic radiological feature of AIP, and this pancreatographic finding on ERCP is mandatory in the Japanese diagnostic criteria for AIP[11]. We previously compared the pancreatograms of 17 AIP patients having a mass-forming lesion in the pancreatic head and 40 patients with pancreatic head cancer[6]. In the present study, we further compared pancreatograms of 48 AIP patients and 143 PC patients, and evaluated more accurately by further date.

Although pancreatographic findings are useful to differentiate AIP and PC, ERCP can cause adverse effects, such as pancreatitis. Since magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has become popular as a non-invasive method for obtaining high quality images of the pancreaticobiliary tree, MRCP is replacing diagnostic ERCP in many pancreatobiliary diseases. In the new Korean diagnostic criteria, AIP can be diagnosed by MRCP without the need for ERCP[12]. In our previously study of the utility of MRCP for diagnosing AIP in 20 AIP patients who were examined before 2008, MRCP could not replace ERCP, because narrowing of the MPD in AIP was not visualized on MRCP[13]. However, with development of MRCP models, spatial resolution of the pancreatic duct has improved on MRCP. We again studied the usefulness of MRCP for diagnosing AIP in 30 AIP patients and assessed whether MRCP could replace ERCP for diagnosing AIP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From 1992 to August 2010, pancreatograms on ERCP were obtained in 48 AIP patients [34 males, 14 females; age, 64.1 ± 12.1 (mean ± SD) years; age range, 27-83 years]. They were diagnosed as having AIP according to the Asian Diagnostic Criteria for AIP[12]: pancreatic enlargement on computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography (US) (n = 48), irregular narrowing of the MPD on ERCP (n = 48), elevated serum IgG4 (n = 42), presence of autoantibodies (n = 26), histological findings of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis (LPSP, n = 18), and steroid responsiveness (n = 38). Overall, 23 patients had diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, and 25 patients had segmental enlargement of the pancreas (head, n = 17; body and/or tail, n = 8). An initial dose of oral prednisolone of 30-40 mg/d was administered for 2-3 wk. It was then tapered by 5 mg every 1-3 wk until it reached 5 mg/d. After about three months of induction, maintenance therapy of 2.5-5 mg/d was administered for six months to 143 mo. Malignant diseases, such as pancreatic or biliary cancers, were excluded by long follow up in the 30 patients without histological examination. During the same period as the AIP cases, ERCP pancreatograms were examined in 143 PC patients (81 males, 62 females; age, 63.5 ± 10.9 years; range, 42-79 years). These PCs were resected or histologically confirmed after adequate imaging studies, such as US, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The locations of PC were confirmed to include the head (n = 88), body (n = 37), and tail (n = 18) on these imaging examinations.

The pancreatographic findings were evaluated in the 44 AIP patients and the 143 PC patients to measure the length of the narrowed MPD and the diameter of the upstream MPD (dilated MPD above the narrowed part). It was also determined whether obstruction and skipped lesions in the MPD (discrete narrowed lesions scattered in the almost normal MPD) or side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the MPD were present. The length of the narrowed MPD and the maximal diameter of the dilated upstream MPD were measured using measuring function on computerized images or a manual goniometer. The cholangiographic findings were evaluated to identify morphological modifications in the 38 AIP patients and 77 PC patients with bile duct involvement.

Furthermore, 30 of the 48 AIP patients also underwent MRCP within three weeks, and MRCP and ERCP findings were compared. MRCP was performed using a 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging machine (INTERA, Philips Co. Ltd., The Netherlands) by two-dimensional (up to 2005) and three-dimensional (2006-2010), coronal, heavily T2-weighted, signal-shot, rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement. Since 2006, a 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging machine (MAGNETOM Avanto, Siemens Co. Ltd., Germany) was also used. Diagnostic accuracies for AIP on ERCP and MRCP were compared separately in diffuse-type AIP patients (n = 16) and segmental-type AIP patients (n = 14). Two endoscopists and radiologists, who were blind to clinical information, reviewed the radiological findings.

Statistical analyses were performed with the Mann-Whitney’s U test and Fisher’s exact probability test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Pancreatographic differences between AIP and PC

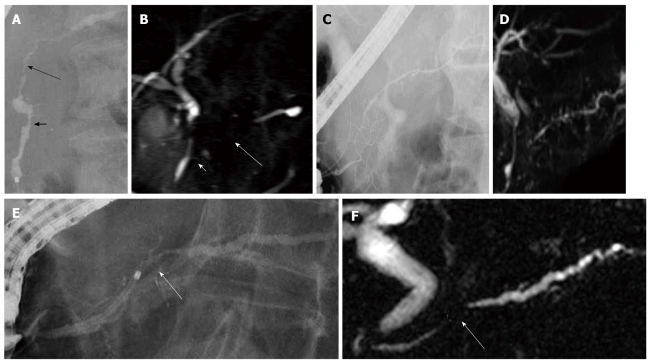

Whereas obstruction of the MPD was more frequently detected in PC (AIP: 4% vs PC: 69%, P < 0.001), skipped lesions of the MPD were detected only in AIP (27% vs 0%, P < 0.001) (Figure 1A), and side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the MPD was more frequent in AIP (81% vs 22%, P < 0.001) (Figure 1C). The narrowed MPD was longer in AIP (7.6 ± 4.3 cm vs 2.5 ± 0.9 cm, P < 0.001), and a narrowed MPD longer than 3 cm was more frequent in AIP (90% vs 27%, P < 0.001). The maximal diameter of the upstream MPD was smaller in AIP (2.9 ± 0.8 mm vs 6.8 ± 2.1 mm, P < 0.001), and upstream dilatation of the MPD less than 5 mm was more frequent in AIP (95% vs 27%, P < 0.001) (Figure 1E) (Table 1). A short narrowed MPD was difficult to differentiate from stenosis of the MPD in PC (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Pancreatography of autoimmune pancreatitis. A: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography finding of autoimmune pancreatitis showing skipped lesions of the main pancreatic duct (short and long arrows); B: On magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, skipped lesions (short and long arrows) on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography were not visualized; C: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography finding of autoimmune pancreatitis showing side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the main pancreatic duct; D: Recent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography could show diffuse narrowing of the main pancreatic duct fairly well; E: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography finding of autoimmune pancreatitis showing a short narrowed main pancreatic duct (arrow) with upstream dilatation less than 5 mm; F: On magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, the narrowed portion (arrow) was not visualized.

Table 1.

Pancreatographic differences between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer n (%)

| Autoimmune pancreatitis (n = 48) | Pancreatic cancer (n = 143) | P-value | |

| Obstruction of the MPD +/- | 2/46 (4) | 98/45 (69) | < 0.001 |

| Skipped lesions of the MPD +/- | 13/35 (27) | 0/143 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Side branch derivation from the narrowed MPD +/- | 39/9 (81) | 10/35 (22) | < 0.001 |

| Length of the narrowed MPD (cm) | 7.6 ± 4.3 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Length of the narrowed MPD > 3 cm +/- | 43/5 (90) | 12/33 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Diameter of upstream MPD (mm) | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Diameter of upstream MPD < 5 mm +/- | 19/1 (95) | 12/33 (27) | < 0.001 |

MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

Cholangiographic differences between AIP and PC

Stenosis of the lower bile duct was smooth in 33 (87%) AIP patients, but irregular in 50 (65%) PC patients (P < 0.001). Left-side deviation of the lower bile duct was detected in both groups. Stenosis of the intrahepatic or hilar bile duct was detected in only six AIP patients (P = 0.001) (Figure 2) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography finding of autoimmune pancreatitis showing stenosis of the hilar and intrahepatic bile duct.

Table 2.

Cholangiographic differences between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer n (%)

| Autoimmune pancreatitis | Pancreatic carcinoma | P-value | |

| Stenosis of the lower bile duct | n = 38 | n = 77 | |

| Smooth stenosis | 33 (87) | 27 (35) | < 0.001 |

| Irregular stenosis | 5 (13) | 50 (65) | |

| Left-side deviation of the lower bile duct +/- | 20 (53) | 49 (64) | NS |

| Stenosis of the intra/hilar bile duct | 6 (16) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

NS: Not significant.

Diagnostic accuracy for AIP by ERCP and MRCP

In diffuse-type AIP, diffuse narrowing of the MPD on ERCP was shown as skipped non-visualized lesions in 50% (Figure 1B), faint visualization in 19%, and non-visualization in 31% on MRCP. Diffuse narrowing of the MPD could be fairly well visualized in two recent patients (Figure 1D). Side branches from the narrowed portion of the MPD shown on ERCP were visualized faintly only in 21% on MRCP. Stenosis of the bile duct was also detected on MRCP. After steroid therapy, the MPD was visualized in 100%, and the branches were visualized in 50% on MRCP. Resolution of bile duct lesions was seen completely in 53% and incompletely in 47% on MRCP (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy for diffuse-type autoimmune pancreatitis by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

| ERCP before steroid |

MRCP |

|

| Before steroid | After steroid | |

| MPD narrowing | Skipped non-visualization 8 (50%) | Visualization 16/16 (100%) |

| (n = 16) | Faint visualization 3 (19%) | |

| Non-visualization 5 (31%) | ||

| Branches from the narrowed MPD (n = 14) | Faint visualization 3 (21%) | Visualization 7/14 (50%) |

| Non-visualization 11 (79%) | ||

| Bile duct stenosis (n = 15) | Stenosis 15 (100%) | Resolution |

| Complete 8/15 (53%) | ||

| Incomplete 7/15 (47%) | ||

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

In segmental-type AIP, segmental narrowing of the MPD on ERCP was shown as faint visualization in 14% and non-visualization in 86% on MRCP (Figure 1F). Side branches from the narrowed MPD shown on ERCP were visualized faintly only in 18% on MRCP. After steroid therapy, the MPD was visualized in 100%, and the branches were visualized in 60% on MRCP. Resolution of bile duct lesions was seen completely in 50% and incompletely in 50% on MRCP (Figure 3A and B) (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography finding of autoimmune pancreatitis. Stenosis of the lower bile duct (short arrow) and the narrowing of the main pancreatic duct (long arrow) (A) improved after steroid therapy (B).

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy for segmental-type autoimmune pancreatitis by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

| ERCP before steroid |

MRCP |

|

| Before steroid | After steroid | |

| MPD narrowing (n = 14) | Faint visualization 2 (14%) | Visualization 10/10 (100%) |

| Non-visualization 12 (86%) | ||

| Branches from the narrowed MPD (n = 11) | Faint visualization 2 (18%) | Visualization 6/10 (60%) |

| Non-visualization 9 (82%) | ||

| Bile duct stenosis (n = 8) | Stenosis 8 (100%) | Resolution |

| Complete 4/8 (50%) | ||

| Incomplete 4/8 (50%) | ||

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

DISCUSSION

AIP responds dramatically to steroid therapy; therefore, it is of the utmost importance that AIP be differentiated from PC to avoid unnecessary laparotomy or pancreatic resection. Histopathological findings of AIP in Japan are characterized by dense infiltration of T lymphocytes and IgG4-positive plasma cells, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis in the pancreas; this is called LPSP. Abundant lymphoplasmacytic cells infiltrate around interlobular ducts with fibrosis, especially the medium and large ducts, including the MPD. The periductal inflammation is usually extensive and distributed throughout the entire pancreas. However, the degree and extent of periductal inflammation differ from duct to duct according to the location of the involved pancreas. The infiltrate is primarily subepithelial, with the epithelium only rarely being infiltrated by lymphocytes. It encompasses the ducts and narrows their lumen by infolding of the epithelium. If the inflammatory process affects the pancreatic head, it usually also involves the lower common bile duct, where it leads to a marked thickening of the bile duct wall due to fibrosis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. The epithelium of the bile duct is also well preserved. The thickening of the bile duct wall sometimes spreads extensively to the bile duct, where stenosis is not apparent on cholangiography[4,14-16]. On the other hand, PC cells infiltrate scirrhously, destroy the epithelium of the pancreatic and bile ducts, and frequently obstruct the main and branch pancreatic ducts. These histopathological differences around the ducts represent the different cholangiopancreatographic findings between AIP and PC. Pancreatographic findings, such as no obstruction of the MPD, skipped lesions of the MPD, side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the MPD, narrowed portion of the MPD > 3-cm-long, a maximal diameter < 5 mm of the upstream MPD, and smooth stenosis of the lower bile duct are highly suggestive of AIP rather than PC. Stenosis of the intrahepatic or hilar bile duct is recognized as other organ involvement of AIP and supports the diagnosis of AIP rather than PC, although it should be distinguished from cholangiocarcinoma and primary sclerosing cholangitis[17,18]. Wakabayashi et al[19] compared pancreatograms of nine segmental-type AIP patients and 80 PC patients. They reported that obstruction of the MPD was frequent in PC [11% (1/9) vs 60% (48/80)]. A narrowed portion of the MPD ≥ 3-cm-long [100% (8/8) vs 22% (6/27)] and a maximal diameter < 4 mm of the upstream MPD [(67% (4/6) vs 4% (1/23)] were frequently detected in AIP, and side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the MPD was detected in 50% (4/8) of AIP patients[19]. In Nakazawa’s cholangiopancreatographic study of 37 AIP patients, skipped lesions of the MPD were detected in six (16%) patients, and stenosis of the intrahepatic or hilar bile duct was detected in 16 (43%) patients[20].

The major problem with MRCP for diagnosing AIP is that the narrowed MPD seen on ERCP cannot be visualized on MRCP, because of the inferior resolution of MRCP compared with ERCP. Segmental narrowing of the MPD seen on ERCP was not visualized in 86% on MRCP, and distinguishing between AIP and PC was quite difficult on MRCP. However, in these cases, less upstream dilatation of the MPD on MRCP may suggest AIP rather than PC. In diffuse-type-, diffuse narrowing of the MPD on ERCP was shown as skipped, non-visualized lesions in 50% and faintly visualized in 19% on MRCP. With the development of MRCP models, diffuse narrowing of the MPD could be visualized fairly well on MRCP in two recent patients. Skipped, non-visualized lesions and a faintly visualized, narrowed MPD can suggest AIP with typical diffuse enlargement of the pancreas on CT or MRI. Side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the MPD is a useful pancreatographic finding suggesting AIP, but the finding can rarely be seen on MRCP. However, stenosis of the bile duct was also detected on MRCP and resolution of the pancreatic and bile ducts after steroid therapy can be fully evaluated on MRCP. Park et al[21] also reported that skipped MPD narrowing and less upstream MPD dilatation on MRCP suggest AIP. Although secretin is not available in Japan currently, secretin-MRCP is reported to enable demonstration of the integrity of the MPD and lead to a correct diagnosis of AIP[22].

In conclusion, the following ERCP findings are fairly specific for AIP and are useful to differentiate AIP from PC: less obstruction of the MPD, skipped lesions of the MPD, side branch derivation from the narrowed portion of the MPD, length of the narrowed MPD > 3 cm, maximal diameter of the upstream < 5 mm, smooth stricture of lower the bile duct, and stenosis of intra or hilar bile duct. Although MRCP cannot fully replace ERCP for the diagnostic evaluation of AIP, MRCP may deserve to be used in some diffuse-type AIP cases and is useful for follow-up of AIP.

COMMENTS

Background

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a peculiar type of pancreatitis of presumed autoimmune etiology. Since AIP responds dramatically to steroid therapy, it is most important that AIP be differentiated from pancreatic cancer (PC) to avoid unnecessary laparotomy or pancreatic resection. However, some cases were still difficult to distinguish between AIP and PC.

Research frontiers

Pancreatographic findings to facilitate differentiating between AIP and PC on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were investigated.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Obstruction of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) was more frequently detected in PC. Skipped MPD lesions and side branch derivation from the narrowed MPD were detected in AIP. The narrowed MPD was longer in AIP. Maximal diameter of the upstream MPD was smaller in AIP. Stenosis of the lower bile duct was smooth in AIP and irregular in PC patients. Stenosis of the intrahepatic or hilar bile duct was detected only in AIP. Diffuse narrowing of the MPD on ERCP was shown as a skipped non-visualized lesion in 50% and faint visualization in 19% on MRCP.

Applications

Several ERCP findings are useful to differentiate AIP from PC. MRCP cannot replace ERCP for the diagnostic evaluation of AIP, but some MRCP findings support the diagnosis of AIP.

Peer review

This is a well-written manuscript about pancreatography for diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis and is of some interest.

Footnotes

Supported by The Research Committee on Intractable Diseases provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan

Peer reviewer: De-Liang Fu, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Surgery, Pancreatic Disease Institute, Fudan University, 12 Wulumqi Road (M), Shanghai 200040, China

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Hayashi Y, Funata N. Gastrointestinal findings in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1127–1130. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugumar A, Chari ST. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:513–518. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833d118b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Ito T, Inui K, Irie H, Irisawa A, Kubo K, Notohara K, Hasebe O, et al. Japanese clinical guidelines for autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2009;38:849–866. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b9ee1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Sasaki T. Autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kamata N. Clinical difficulties in the differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2694–2699. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamisawa T, Imai M, Yui Chen P, Tu Y, Egawa N, T suruta K, Okamoto A, Suzuki M, Kamata N. Strategy for differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37:e62–e67. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318175e3a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner TB, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:439–460, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabata T, Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Kurata M, Honda G, Tsuruta K, Setoguchi K, Obayashi T, et al. Serum IgG4 concentrations and IgG4-related sclerosing disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;408:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chari ST, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MA, Vege SS. A diagnostic strategy to distinguish autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raina A, Krasinskas AM, Greer JB, Lamb J, Fink E, Moser AJ, Zeh HJ 3rd, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC. Serum immunoglobulin G fraction 4 levels in pancreatic cancer: elevations not associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:48–53. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-48-SIGFLI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Naruse S, Tanaka S, Nishimori I, Ohara H, Ito T, Kiriyama S, Inui K, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria of autoimmune pancreatitis: revised proposal. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:626–631. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otsuki M, Chung JB, Okazaki K, Kim MH, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Park SW, Shimosegawa T, Lee K, Ito T, et al. Asian diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: consensus of the Japan-Korea Symposium on Autoimmune Pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kodama M, Kamata N. Can MRCP replace ERCP for the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis? Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:381–384. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9401-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Amemiya K, Egawa N, Nakajima H. Close relationship between autoimmune pancreatitis and multifocal fibrosclerosis. Gut. 2003;52:683–687. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klöppel G, Sipos B, Zamboni G, Kojima M, Morohoshi T. Autoimmune pancreatitis: histo- and immunopathological features. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 18:28–31. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandan VS, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Abraham SC. Patchy distribution of pathologic abnormalities in autoimmune pancreatitis: implications for preoperative diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1762–1769. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318181f9ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, Smyrk TC, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:706–715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Kurata M, Honda G, Tsuruta K. Sclerosing cholangitis associated with autoimmune pancreatitis differs from primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2357–2360. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakabayashi T, Kawaura Y, Satomura Y, Watanabe H, Motoo Y, Okai T, Sawabu N. Clinical and imaging features of autoimmune pancreatitis with focal pancreatic swelling or mass formation: comparison with so-called tumor-forming pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2679–2687. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, Ando T, Imai H, Takada H, Hayashi K, Kitajima Y, Joh T. Difficulty in diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis by imaging findings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SH, Kim MH, Kim SY, Kim HJ, Moon SH, Lee SS, Byun JH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Lee MG. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for the diagnostic evaluation of autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2010;39:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181dbf469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carbognin G, Girardi V, Biasiutti C, Camera L, Manfredi R, Frulloni L, Hermans JJ, Mucelli RP. Autoimmune pancreatitis: imaging findings on contrast-enhanced MR, MRCP and dynamic secretin-enhanced MRCP. Radiol Med. 2009;114:1214–1231. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]