Abstract

A crossed-loop (orthogonal mode) resonator (CLR) was constructed of fine wire to achieve design goals for rapid scan in vivo EPR imaging at VHF frequencies (in practice, near 250 MHz). This application requires the resonator to have a very open design to facilitate access to the animal for physiological support during the image acquisition. The rapid scan experiment uses large amplitude magnetic field scans, and sufficiently large resonator and detection bandwidths to record the rapidly-changing signal response. Rapid-scan EPR is sensitive to RF/microwave source noise and to baseline changes that are coherent with the field scan. The sensitivity to source noise is a primary incentive for using a CLR to isolate the detected signal from the RF source noise. Isolation from source noise of 44 and 47 dB was achieved in two resonator designs. Prior results showed that eddy currents contribute to background problems in rapid scan EPR, so the CLR design had to minimize conducting metal components. Using fine (AWG 38) wire for the resonators decreased eddy currents and lowered the resonator Q, thus providing larger resonator bandwidth. Mechanical resonances at specific scan frequencies are a major contributor to rapid scan backgrounds.

Keywords: bimodal resonator, isolation, rapid scan

INTRODUCTION

In many electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiments, signal to noise (S/N) is limited by source noise. This is especially a problem for dispersion operation. High-power pulsed EPR experiments such as electron spin echo (ESE) require protection of the sensitive EPR signal detector from the high power pulses used to create the signal. For these reasons, there is a long tradition dating back to Teaney et al. (1) of building bimodal resonators in which the excitation resonator is isolated from the EPR signal resonator. Background literature was cited in Tsapin and Hyde (2).

A bimodal LGR concept with perpendicular resonators was illustrated in Hyde and Froncisz (3). Tsapin and Hyde (2) fabricated and bench tested an X-band implementation of this concept. Hyde subsequently informed us that although not stated in this paper (2), there were conducting plates on the outside of the resonator to constrain the return flux from the two resonators, so this resonator was more similar to those that we built than we realized at the time. An S-band bimodal resonator, using two aluminum loop-gap resonators in coaxial juxtaposition, was described by Piasecki et al. (4). Our prior S-band (5,6), L-band (7), and VHF (8) crossed loop (bimodal) resonators (CLR) were constructed of solid copper alloy with a principal goal of maximizing the isolation between the two resonators. The VHF resonator was also designed with rapid Q-switching of the two resonators to optimize pulse power use and minimize dead time of the echo or free induction decay (FID) EPR signal.

In the rapid scan EPR experiment there are experimental artifacts that are suppressed substantially by the slow-scan continuous wave (CW) experiment when implemented with small-amplitude magnetic field modulation and narrow-band lock-in detection at the modulation frequency. The normal slow-scan CW measurement flattens the baseline and filters out high-frequency noise. The rapid scan experiment uses larger amplitude magnetic field scans, and sufficiently large resonator and detection bandwidths to record the rapidly-changing signal response. High frequency noise and baseline changes that are not coherent with the field scan can be reduced by time averaging the signal. However, rapid-scan EPR is sensitive to RF/microwave source noise and to baseline changes that are coherent with the field scan. The sensitivity to source noise is a primary incentive for using a CLR to isolate the detected signal from the RF source noise in rapid scan experiments.

In a reflection resonator, isolation of the source from the detector is obtained by critical coupling of the resonator to the transmission line. Since the coupling is frequency sensitive, this type of isolation is not effective in reducing the phase noise from the source that reaches the detector. In the CLR, phase noise from the source still causes noise current to flow in the driven resonator. However, this noise is isolated from the detector by the fact that the fields in the two resonators are essentially perpendicular. An isolation of 20 dB between the two resonators of the CLR reduces the RF source noise by 20 dB, which often will be sufficient to reduce source noise to a level below thermal noise. At VHF frequencies (~ 250 MHz) it is common to achieve CLR isolation of at least 40 dB.

Very rapid scans permit measuring short electron spin relaxation times, as illustrated by the measurement of T2 for a nitroxyl radical in fluid solution (9). The faster and larger the magnetic field-scan, the larger the background signal induced by the scanning field. The background signal is due to mechanical effects in the resonator that are coherent with the scanning field and, therefore, do not cancel with time averaging. This background signal has been greatly suppressed by the use of filters to isolate the scan coils from the RF field in the resonator and by making the CLR more mechanically stable. The smaller the background signal, the more useful the rapid scan methodology. Tseitlin et al. (10) developed a Fourier expansion method for subtracting the background signal from the EPR signal. The closer the background signal is to the fundamental of the scan frequency, the more effective this removal method. Reducing the background signal will be especially important for image reconstruction from rapid scan data, since some projections used for image reconstruction have inherently low S/N (11). Our tests indicate that the residual backgrounds are primarily the result of mechanical resonances at specific sweep frequencies. Backgrounds can be minimized by avoiding these resonant frequencies.

The CLR described in this paper simultaneously addresses two demanding design specifications. First, since the CLR is intended for in vivo imaging at VHF frequencies (in practice, near 250 MHz), the resonator has to have a very open design to facilitate access to the animal for physiological support during the image acquisition. Second, based on our experience with background problems in rapid scan EPR, we concluded that the design had to minimize conducting metal components. Initially, there was the possibility that magnetic susceptibility as well as electrical conductivity could be important, but resonators built with “zero susceptibility” wire (obtained from Doty Scientific) did not show significant improvements. Consequently, eddy currents became the design focus. Increasing the resistance decreases eddy currents. Fortunately, increasing resistance fits with two aspects of the CLR design: the open design is better achieved with wire loops than with the solid copper alloy designs of our prior CLR, and the need for large resonator bandwidth (low Q) is achieved by increasing the resistance of the resonator. The smaller the diameter of the wire, the higher the resistance, and therefore the lower the Q. Thus, using a small-diameter wire both lowers the Q and reduces the eddy current problems. However, the small diameter wire has to be rigidly supported. Various mechanical tests suggested that the orientation of the coax transmission line relative to the magnetic field is also important, so the resonator design reported in this paper has the coax parallel to the external field instead of perpendicular to the field as in almost all other EPR resonator and transmission line assemblies.

Another consideration is the interaction of the magnetic field scan coils with the resonator. This is the primary source of baseline shifts that are coherent with the field scan and produce the background signal referred to above. There are a number of ways that the field scan coils can interact with the resonator. When there is no RF shield between the resonator and the scan coils, as is the case in our design, there is a direct induction of RF current into the scan coils which is dependent, most likely, on the RF impedance of the scan coil driver circuit that changes with scan current. In addition, vibration of the scan coils caused by the interaction of the steady magnetic field and the scanning field can change RF current induced into the scan coils. If the vibrations are transmitted to the resonator, this can cause changes in tuning and resonant frequency. We have shown that mechanical resonances at specific scan frequencies are a major contributor to rapid scan backgrounds.

RESONATOR DESIGN

Earlier designs of CLRs were limited in terms of filling factor because the two loops were essentially the same size and the effective volume is that common volume where the two loops cross. In the design for the CLR described here, the diameter of the excitation loop is larger than the length or diameter of the sample loop and excites the spins in the sample loop quite uniformly and, therefore, the effective filling factor is the same or better than it would be if the sample loop was used as a reflection resonator.

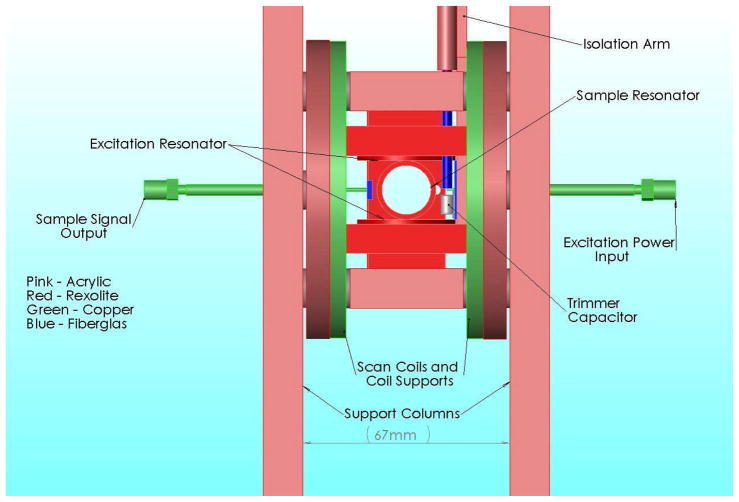

A sketch of the VHF CLR is shown in Figure 1. The 89 mm diameter Helmholtz scan coils consist of 50 turns each of AWG 20 enameled copper wire, are epoxy encapsulated and epoxied to the acrylic scan coil supports. The sample resonator is 16 mm in diameter and 15 mm long. The excitation resonator consists of two coils 32 mm in diameter spaced 20 mm apart. The sample resonator is rigidly attached to the support columns via brass screws extending through the scan coil supports. The excitation resonator is mounted via pivots, in the support columns, concentric with the two coax-cables such that its axis can be rotated very precisely relative to the axis of the sample resonator by means of a screw arrangement at the top of the isolation arm, which controls the isolation between the two resonators.

Figure 1.

Sketch of VHF CLR, showing the arrangement of the two resonators and scan coils.

The physical size of a wire resonator depends on the resonant frequency and the number of turns of wire. A single-turn wire loop resonator would be self-resonant when the circumference of the loop is on the order of 1/2 wavelength. However, the magnetic field inside a self-resonant resonator would be very non-uniform. Therefore a practical one-turn EPR resonator should be less than about ¼ wavelength in circumference. This means that at a resonant frequency of 250 MHz (λ = 1200 mm), a single loop resonator should be less than about 95 mm in diameter. For multi-turn wire loop resonators, the diameter of the turns should be further reduced by at least the number of turns squared and even further due to inter-wire capacitances.

In the VHF CLR, the excitation resonator consists of 2 turns in series which would limit its diameter to about 24 mm. The larger size, 32 mm excitation resonator diameter is made possible by inserting capacitances in series between the 2 loops. This essentially makes each loop a separate resonant circuit and reduces the chances of self-resonance. In the present design each loop of the excitation resonator consists of 2 series turns of AWG No. 38, 0.1 mm (0.004 in) diameter bare copper wire and the two coils have a total of 4 series capacitors. Three of the capacitors are 0.64 mm square ceramic chip capacitors from Voltronics and the 4th capacitor is a 1 to 5 pF trimmer capacitor from the same source. The trimmer allows tuning of the resonator to the same frequency as the sample resonator. A parallel chip capacitor is used at the coax feed point to the resonator to adjust to near critical coupling. Precise critical coupling of either resonator is not required in a CLR, because reflections from the excitation resonator are isolated from the detector. The resonator wires are wound on a machined raised circle on the surface of a 12.7 mm thick Rexolite® (polystyrene) structure.

The sample resonator consists of 6 turns of AWG No. 38 wire with a chip capacitor between each 1-1/2 turns and also at the two ends of the winding; a total of 5 capacitors. A parallel capacitor is again used to adjust to near critical coupling and no provision for tuning the resonant frequency is provided. The use of multiple capacitors in series reduces the effect of stray capacitances and reduces the change in resonant frequency when the sample is inserted. The resonator wires are wound over a thin, 0.09 mm (0.0035in) thick plastic sheet on the outside of a 16 mm mandrel. The wires and capacitors are then covered with Q-dope (solvent dissolved polystyrene) and mounted inside a Rexolite® support structure.

Both resonators are fed with ¼ wave bazooka baluns (12) constructed of 3.36 mm (0.14 in) outside diameter semi-rigid coax with the center conductor replaced by a 1.2 mm (0.047 in) outside diameter semi-rigid coax.

The present design of the VHF CLR does not have an RF shield between the CLR and the scan coils; rather an RF shield surrounds the entire assembly. As the scan coils are swept, the RF impedance looking into the coil driver output is a function of the driving current. Therefore, there is a change in energy in the sample resonator that is coherent with the field scan waveform and a potential for producing a background signal superimposed on the recorded rapid scan signal. In order to produce the required current waveform over a range of frequencies, the scan driver uses a feedback circuit that monitors the scan coil current and maintains the required voltage waveform to provide a linear field sweep (triangular waveform) current to the scan coils. Excessive stray capacitance from the coil driver leads to ground produces an unmonitored current component that can cause the driver circuit to become unstable. Therefore, filters that have capacitance to ground or between the coil driver leads are not usable. Instead, a wave-trap consisting of a parallel combination of inductance and tunable capacitance is inserted into each lead of the coil driver. This has been found to be effective in decoupling the coil driver from the scan coils for RF frequencies near resonance of the CLR. An experiment was performed in which the scan coils were wrapped completely, except for a small gap, with copper tape which was connected to a shield around the coil driver leads inside the RF shield. This was also found to be effective in reducing scan coil – resonator RF interactions, but produced excessive capacitance to ground, making the scan coil driver unstable and was abandoned.

Experimental Measurements and Resonator Refinement

Several versions of the design concepts outlined above were built and tested in the 250 MHz rapid scan spectrometer (13). In a test of the ability of the CLR to suppress source phase noise, the source was artificially FM modulated with a noise source to increase its phase noise. This was required in order to pass enough noise through the CLR to be measurable. It was found that, for both absorption and dispersion, the measured noise level, after correction for differences in spectrometer gain and 20 dB higher noise in the CLR, was 42 dB ± 1 dB below the noise measured in a similar test of a typical reflection resonator of approximately the same Q. The isolation of the CLR, as measured on a network analyzer, was 42 dB ± 0.5 dB, demonstrating that the r.f. isolation of the CLR translates directly into source phase noise suppression in the signal. The key experimental observable that stimulated refinements in the design of the resonator is the background signal.

Our current hypothesis is that the rapidly-scanning magnetic field induces eddy currents in any conducting material in the resonator or shield assembly, and that the resultant forces cause slight changes in the frequency and/or match of the resonator that are coherent with the magnetic field scan. This results in a change in the RF that is detected along with the EPR signal, independent of whether there is an EPR signal. The dependence on external magnetic field makes it difficult to fully subtract the signal if the background is recorded very far off resonance. The background can have multiple harmonics and phase changes that can confound the interpretation, with field dependence sometimes making it look almost like an EPR signal.

Tables 1 and 2 show the comparison between measured results for two versions of the VHF CLR; an earlier version, CLR-1, and the latest version, CLR-2. The resonators for the two CLRs are essentially the same except as follows. All non-conducting parts of CLR-1 were constructed of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic and those for CLR-2 were Rexolite® (polystyrene plastic) for resonator supports and acrylic for other support structures. The support for the excitation resonator in CLR-1 is 3 mm (1/8 in) PVC and that for CLR-2 is 12.7 mm (1/2 in) Rexolite® for rigidity. The support for the sample resonator is 12.7 mm PVC for CLR-1 and 12.7 mm Rexolite® for CLR-2. The excitation resonator for CLR-1 has one turn of AWG 38 wire in each coil and each coil for CLR-2 has 2 series turns of AWG 38 wire spaced 1 mm apart and separated by a chip capacitor. The coaxial baluns run in a radial direction from near the axis of the scan coils in CLR-1 and they run along the axis of the scan coils in CLR-2 to present a smaller cross-section to the scan field.

Table 1.

Measured Parameters for the CLRs and Scan Coils

| CLR resonator | Qsource | Qdetector | Best isolation | Scan coil inductance | Scan coil resistance | Scan coil field constant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLR-1 | 35 | 30 | 47 dB | 1.2 mH | 1.8 ohms | 10.12 G/A |

| CLR-2 | 66 | 54 | 44 dB | 1.2 mH | 1.8 ohms | 10.06 G/A |

Table 2.

Resonator Performance

| CLR resonator | Normalized S/N obtained under same conditions with no significant background. | Mechanical resonance frequencies (kHz) | Normalized background amplitudes at worst mechanical resonance. | Normalized ratio of standard signal to worst background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLR-1 | 1 | 1.04, 1.18, 2.25 | 1.62 | 1 |

| CLR-2 | 1.67 | 1.07 | 1 | 2.73 |

The two CLRs were tested on the same locally-built VHF rapid scan EPR spectrometer (8) under identical conditions.

Discussion of Results

A 25 mm VHF resonator constructed from solid copper alloy (e.g., as described in (8)) has a Q of about one thousand, and resultant narrow bandwidth. As shown in Table 1, the desired lower Q was achieved by constructing the CLR with fine wire. The isolation between the two resonators of the CLR was nearly as high in the open design wire CLR described here (see Table 1) as in the carefully enclosed solid metal CLR (8).

During the iterative design and construction of the wire CLR it was found that the background signals during rapid scan EPR were maximized at specific scan frequencies in the kHz region. The two CLR described were designed with different thicknesses of support pieces to test the importance of rigidity of the support. The mechanical resonance frequencies and amplitudes of background signals listed in Table 2 confirm that the background signals are mechanical in origin and are maximized at specific mechanical resonance frequencies.

Acknowledgments

Development of rapid scan EPR is supported by NIH NIBIB grant R01EB000557 and is a collaborative project of the Center for EPR Imaging in Vivo Physiology supported by NIH NIBIB P41 EB002034 (Howard Halpern, PI). CLR-1 described here has been provided to Dr. Halpern for in vivo studies. Mark Teitlin performed analyses of the harmonic content of the background signals. We thank Sandra S. Eaton for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Teaney DT, Klein MP, Portis AM. Microwave Superheterodyne Induction Spectrometer. Rev Sci Instrum. 1961;32:721–729. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsapin AI, Hyde JS, Froncisz W. Bimodal loop-gap resonator. J Magn Reson. 1992;100(3):484–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyde JS, Froncisz W. Loop gap resonators. In: Hoff AJ, editor. Advanced EPR: Applications in Biology and Biochemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. pp. 277–306. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piasecki W, Froncisz W, Hyde JS. Bimodal loop-gap resonator. Rev Sci Instrum. 1996;67(5):1896–1904. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Ghim BT, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Dispersion and superheterodyne EPR using a bimodal resonator. J Magn Reson A. 1996;122(1):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Ghim BT, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Easily tunable crossed-loop (bimodal) EPR resonator. J Magn Reson A. 1996;122(1):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton GR. An L-Band crossed-loop (bimodal) EPR resonator. J Magn Reson. 2000;144(1):85–88. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. 250 MHz crossed loop resonator for pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance. Magn Reson Engineer. 2002;15:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseitlin M, Dhami A, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Electron Spin T2 of a Nitroxyl Radical at 250 MHz Measured by Rapid Scan EPR. Appl Magn Reson. 2006;30:651–656. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseitlin M, Czechowski T, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Background Removal Procedure for Rapid Scan EPR. J Magn Reson. 2009;196:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseitlin M, Dhami A, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. Comparison of Maximum Entropy and Filtered Back-Projection Methods to Reconstruct Rapid-Scan EPR Images. J Magn Res. 2007;184:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balanis CA. Antenna Theory Analysis and Design. NY: Harper Row; 1982. pp. 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. A pulsed and continuous wave 250 MHz electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometer. Magn Reson Engineer. 2002;15:59–91. [Google Scholar]