Abstract

Objective

Recent studies have found that a subset of young adult survivors of childhood cancer report posttraumatic stress symptoms in response to their diagnosis and treatment. However, it is unclear if these symptoms are associated with impairment in daily functions and/or significant distress, thereby resulting in a clinical disorder. Furthermore, it is unknown whether this disorder continues into very long-term survivorship, including the 3rd and 4th decades of life. This study hypothesized that very long-term survivors of childhood cancer would be more likely to report symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, with functional impairment and/or clinical distress, compared to a group of healthy siblings.

Patients and Methods

6,542 childhood cancer survivors over the age of 18 who were diagnosed between 1970 and 1986 and 368 siblings of cancer survivors completed a comprehensive demographic and health survey.

Results

589 survivors (9%) and 8 siblings (2%) reported functional impairment and/or clinical distress in addition to the set of symptoms consistent with a full diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Survivors had more than a four-fold risk of PTSD compared to siblings (OR=4.14, 95%CI: 2.08-8.25). Controlling for demographic and treatment variables, increased risk of PTSD was associated with educational level of high school or less (OR=1.51, 95% CI=1.16-1.98), being unmarried (OR=1.99, 95% CI=1.58-2.50), annual income less than $20,000 (OR=1.63, 95% CI=1.21-2.20), and being unemployed (OR=2.01, 95% CI=1.62-2.51). Intensive treatment was also associated with increased risk of full PTSD (OR=1.36, 95% CI 1.06 -1.74).

Conclusions

Posttraumatic stress disorder is reported significantly more often by childhood cancer survivors than by sibling controls. Although most survivors are apparently doing well, a subset report significant impairment that may warrant targeted intervention.

Keywords: childhood cancer, young adult

Recent studies of childhood cancer survivors have found a small number of survivors who report symptoms of posttraumatic stress (1-3). These symptoms include re-experiencing or intrusion of unwanted memories, such as nightmares or flashbacks; avoidance of reminders of the events, such as doctors or hospitals, or numbing of emotional responses; and increased sympathetic arousal, including a heightened startle response to sudden noise and constant monitoring for danger. However, to meet the established criteria for a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM IV) (4), one symptom of re-experiencing, three avoidance symptoms, and two symptoms of increased arousal must be present. In addition, symptoms must be severe enough to cause clinical distress or functional impairment. Symptoms must also be in response to an event that ended at least one month prior to assessment, was perceived as a threat to life or body integrity of self or a loved one, and elicited feelings of horror, intense fear or helplessness.

Previous studies of PTSD in childhood cancer survivors have found a minority of survivors reporting significant symptoms, with as few as 3% of survivors 8 to 20 years old (1) to 20% in young adult survivors (2). Compared to a rate of 8.6% in a recent study of 965 adults attending a primary care clinic (5), young adult survivors, but not younger survivors, appeared to have a significantly increased prevalence of PTSD symptoms. Although no formal assessment of clinical distress or functional impairment was done as a part of the diagnosis, the young adult survivors who reported symptoms of PTSD were less likely to be married, and reported more psychological distress and poorer quality of life across all domains (6). Similar impairments in function have also been described in people with PTSD within the general population (5, 7).

Subsequent studies of PTSD in adult survivors of childhood cancer with sample sizes ranging from 45 to 368 have reported prevalence rates from 13% to 19% (8, 9, 10). PTSD has been associated with female gender, being unemployed, lower educational level, cancer of the central nervous system, and severe late effects or health problems (11). However, these associations have not been consistently reported across studies. Furthermore, there has been no clear assessment of the prevalence of symptoms of PTSD associated with clinical distress and/or functional impairment, which, as stated above, are required criteria for the clinical disorder of PTSD.

The objectives of this study were to use the unique resource of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) to examine 1) the prevalence of PTSD in very long term survivors of childhood cancer compared to a sibling control group, and 2) to examine the association of PTSD with demographic and cancer-related variables.

Methods

Sample

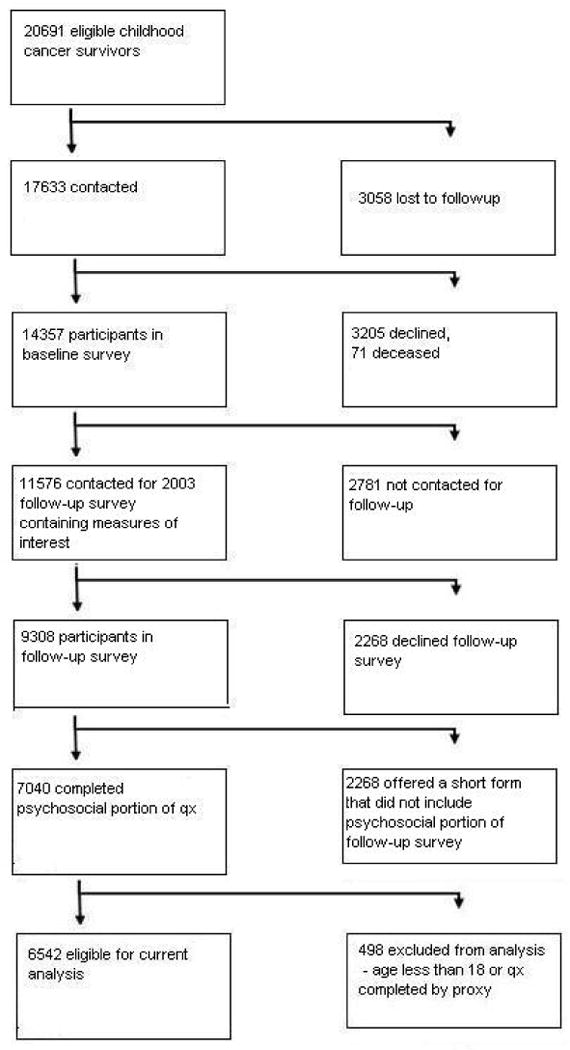

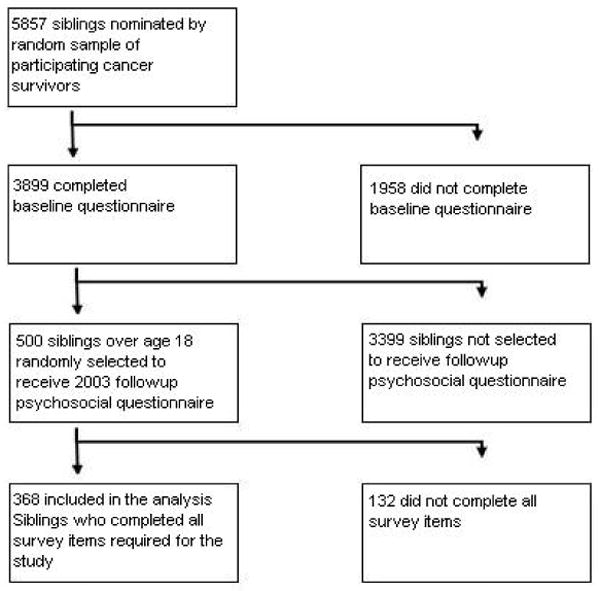

The CCSS is a longitudinal cohort study that tracks the health status of survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed between 1970 and 1986 from collaborating centers (see Appendix 1). The institutional review board at each collaborating center reviewed and approved the CCSS protocol and documents sent to participants. All study participants provided informed consent for participation in the study and for release of medical-record information. Detailed descriptions of the study design and characteristics of the cohort have been reported in previous papers (12-15). Figures 1 and 2 detail how survivors and siblings came to participate in the study. Demographic characteristics of the survivors and siblings participating in this study can be seen in Table 1. Table 2 provides cancer-related descriptive statistics of participating survivors.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the recruitment of the survivor participants in the study.

Figure 2. Flow diagram of the recruitment of the sibling participants in the study.

Table 1. Demographic descriptive statistics of survivors and siblings P-value from robust Wald test.

| Descriptive Statistics for Survivors and Siblings | Sibling | Survivor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p-value | ||

| Age at interview | 18-29 | 134 | 36.4 | 2645 | 40.4 | <.01 |

| 30-39 | 139 | 37.8 | 2769 | 42.3 | ||

| 40+ | 95 | 25.8 | 1128 | 17.2 | ||

| Race | All others | 22 | 6.3 | 815 | 12.5 | <.0001 |

| White non-Hispanic | 330 | 93.8 | 5703 | 87.5 | ||

| Gender | Female | 193 | 52.4 | 3423 | 52.3 | 0.96 |

| Male | 175 | 47.6 | 3119 | 47.7 | ||

| Education | <= High school graduate | 54 | 14.8 | 987 | 15.2 | 0.57 |

| Some college | 125 | 34.2 | 2372 | 36.5 | ||

| >= College graduate | 187 | 51.1 | 3140 | 48.3 | ||

| Employed | No | 58 | 15.8 | 1430 | 22.0 | < .01 |

| Yes | 309 | 84.2 | 5067 | 78.0 | ||

| Personal Income | <$20,000 | 109 | 34.1 | 2688 | 42.4 | <.0001 |

| $20,000-39,999 | 80 | 25.0 | 1892 | 29.8 | ||

| $40,000+ | 131 | 40.9 | 1766 | 27.8 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 102 | 28.0 | 2671 | 41.2 | <.0001 |

| Married/living as married | 218 | 59.9 | 3322 | 51.2 | ||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 44 | 12.1 | 490 | 7.6 | ||

Table 2. Medical descriptive statistics of survivors.

| Variable | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Bone cancer | 604 | 9.2 |

| Central nervous system | 687 | 10.5 | |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 931 | 14.2 | |

| Kidney (Wilms) | 626 | 9.6 | |

| Leukemia | 2183 | 33.4 | |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 504 | 7.7 | |

| Neuroblastoma | 406 | 6.2 | |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 601 | 9.2 | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0-4 | 2395 | 36.6 |

| 5-9 | 1475 | 22.5 | |

| 10-14 | 1414 | 21.6 | |

| 15-20 | 1258 | 19.2 | |

| Year of diagnosis | 1970-1973 | 881 | 13.5 |

| 1974-1978 | 1712 | 26.2 | |

| 1979-1986 | 3949 | 60.4 | |

| Years since dx | 15-19 | 1773 | 27.1 |

| 20-24 | 2343 | 35.8 | |

| 25-29 | 1668 | 25.5 | |

| 30-34 | 758 | 11.6 | |

| Chemotherapy | None | 1246 | 20.3 |

| Anthracycline/Alkylating | 3676 | 59.8 | |

| Other drugs | 1223 | 19.9 | |

| Radiation therapy | RT to brain | 1818 | 29.6 |

| RT, but not to brain | 2060 | 33.5 | |

| No RT | 2087 | 34.0 | |

| RT, site unknown | 176 | 2.9 | |

| 2nd malignancy or recurrence | No | 5364 | 82.0 |

| Yes | 1178 | 18.0 |

Primary outcome variable

PTSD was the primary outcome variable, defined as detailed in Table 3. A dichotomous (yes/no), categorical variable was created using the full diagnostic criteria for PTSD. This included the number and distribution of symptoms specified in the (DSM IV) (1), as well as assessment of functional impairment or clinical distress. All survivors and siblings were considered positive for the Criterion A (exposure to an event threatening life or body integrity of self or loved one) due to the cancer experience, and positive for Criterion E (duration of symptoms for more than one month after the event) given the length of time since the cancer treatment.

Table 3. Definition of PTSD used in this study.

| DSM IV criteria | PTSD criteria used in this study | |

|---|---|---|

| Criteria A | Exposure to event threatening life or body integrity of self or loved one | Diagnosed with cancer or Sibling diagnosed with cancer |

| Criteria B |

Re-experiencing: (1 symptom required) * |

Uncontrollable upsetting thoughts/images Having bad dreams/nightmares Reliving your illness Feeling upset when reminded about illness Physical reactions when reminded about illness |

| Criteria C |

Avoidance: (3 symptoms required)* |

Not thinking/talking/feeling about illness Avoiding activities/people/places that are reminders about illness Forgetting important experiences about illness Less interest in important activities Feeling distant/cut off from people Feeling numb Believing future plans/hopes will not come true |

| Criteria D | Arousal (2 symptoms required)* |

Trouble falling/staying asleep Feeling irritable/having fits of anger Trouble concentrating Overly alert Jumpy/easily startled |

| Criteria E | Duration | More than 30 days after the traumatic event |

| Criteria F | Functional Impairment or Significant Distress | Significant distress defined as T-score ≥ 63 on the Global Status Index (GSI) scale from the BSI or T-score ≥ 63 on any two of the following three BSI factors: Depression, Anxiety, Somatization Functional Impairment defined as T-score ≤ 40 on the “role limitations due to emotional health ” factor from the SF-36 |

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) (16). This measure includes 17 questions covering the three categories of symptoms described above. Each symptom was rated on a 0 to 3 scale for frequency in the past month (0=Not at all or only one time, 1=Once in a while, 2=Half the time, and 3=Almost always). Symptoms rated at 1 or above were counted as present. Using these scoring criteria, the PDS has been shown to have good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, as well as satisfactory convergent and concurrent validity as assessed by clinical diagnoses of PTSD (using a standardized diagnostic interview) and self-report measures of depression and anxiety (17).

The Brief Symptom Inventory – 18 (BSI-18) was used to evaluate psychological distress (18). The BSI-18 is an 18 item self-report questionnaire which generates a summary scale, the global stress index (GSI), and three subscales: depression, anxiety, and somatization. Each item is rated on a 5 point scale, with distress ratings ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Raw scores are converted to age and gender-corrected standard T-scores, using adult non-patient community norms (mean = 50, standard deviation = 10). A T-score greater than or equal to 63 is used to identify clinical cases. The BSI-18 has been validated in healthy volunteers (18) and in earlier administrations with this cohort of cancer survivors (19, 20).

The RAND Health Status Survey, Short Form-36 (RAND SF-36) was used to assess functional impairment. RAND SF-36 is a self report measure that evaluates physical functioning; bodily pain; role limitations due to physical health problems; role limitations due to personal or emotional health; general mental health; social functioning; energy/fatigue; and general health perception (21). Multi-item subscales scores are converted to norm referenced T-scores (mean= 50, standard deviation = 10). Scores ≤ 40 are considered clinically impaired. The RAND SF-36 has received extensive reliability and validity testing (22), and has demonstrated sensitivity in the CCSS cohort (23).

Performance on the BSI-18 and the SF-36 role limitations due to emotional health were used to determine whether survivors met criterion F of the Diagnostic Criterion for PTSD. Those survivors with a GSI score from the BSI-18 that was ≥ 63, or two subscale scores ≥ 63 (i.e. depression, anxiety, or somatization), were determined to meet criterion F based on significant distress. Those survivors who obtained a score ≤ 40 on the role limitations due to emotional health scale from the SF-36 were determined to meet criterion F based on functional limitations.

Independent variables

Specific cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, presence or absence of relapse or new malignancy, year of treatment, years since diagnosis, and intensity of treatment (a yes/no composite variable of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy, detailed in Appendix 2) were analyzed as potential cancer-related predictors of PTSD among survivors. In addition, demographic factors including age at interview, gender, and self-reported employment, marital status, education, ethnicity, and current income were analyzed as potential correlates of PTSD for survivors.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were examined to determine the distribution of variables of interest, and categories were created to balance appropriate distribution of subjects with evaluation of associations relevant to the hypotheses of interest. Races and ethnicities other than Non-Hispanic White were collapsed into one “Other” category, given the small numbers in each of the other self-reported race/ethnic categories.

Descriptive demographic and cancer related characteristics of survivors who completed surveys of interest to this study were compared to those who did not complete the surveys, with p-values from a chi-square test.

Demographic distributions were compared between the survivor and sibling groups using p-values from a robust Wald test (24). The prevalence of PTSD among survivors was compared with siblings, using logistic regression models with robust variance estimates, adjusted for age at interview, gender and intrafamily correlation (25). Given the difference in the racial composition of the survivors and siblings samples, all analyses also adjusted for for race.

Similarly, relationships between PTSD and demographics and treatment among survivors were assessed using logistic regression models. Variables significant at the .05 level in univariate models were employed in a multivariable model, with potential two-way interactions assessed. Due to strong collinearity between diagnosis, intensive treatment, and specific treatments, three models were fit, to examine each of those factors in separate multivariable modeling. All reported p-values are two-sided.

Results

Siblings were similar to survivors in gender and education level, but were more likely to be older at interview (p< .01), white (p<.0001), employed (p<.01), married (p<.0001) and have a higher income (p<.0001). The mean age at interview for survivors was 31.85 years (SD = 7.55; range = 18 - 53), and for siblings was 33.44 years (SD = 8.19; range = 18 - 54). Survivors had a mean age at diagnosis of 8.21 years (SD = 5.87; range = 0 - 20 years). Other specific descriptive data for survivors and siblings can be seen in Tables 2 and 3.

Of the 6,542 childhood cancer survivors and 368 siblings surveyed, 589 (9%) of the survivors and 8 (2%) of the siblings reported the constellation of symptoms plus clinical distress and/or functional impairment consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD (OR=4.14, 95% CI 2.08-8.25, when adjusted for age at interview, race, gender and within-family correlation between survivor and sibling).

Table 4 presents results of multivariable modeling among survivors. PTSD was significantly associated with being unmarried (OR for single vs. married=1.99, 95% CI=1.58-2.50), having an annual income less than $20,000 (OR vs. >$40,000=1.63, 95% CI= 1.21-2.20), being unemployed (OR=2.01, 95% CI= 1.62-2.51), having a high school education or less (OR for high school vs. college graduate=1.51, 95% CI=1.16-1.98), and being over 30 (OR=1.52 for 30-39 vs. 18-29, 95% CI=1.16-2.00). Due to a suggested interaction between gender and race in the sample (p = 0.06), the strata defined by combinations of these factors were examined as separate risk groups. There were no significant associations between these gender and race combinations with PTSD. Models were stratified based on age at diagnosis, due to a significant interaction between radiation and age at diagnosis. Survivors who had cranial radiation under the age of four years were at particularly high risk for PTSD (OR=2.05, 95% CI=1.41-2.97).

Table 4.

Multivariate model for risk of PTSD in survivors, adjusted for all listed variables

| Variables associated with PTSD in Survivors | PTSD N(%) | No PTSD N(%) | Odds ratio (95% C.I.) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex and Race | Male, non-White | 26( 8 ) | 303( 92 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Female, non-White | 49( 13 ) | 315( 87 ) | 1.56 (0.93 – 2.62 ) | 0.09 | |

| Male, White non-Hispanic | 200( 8 ) | 2153( 92 ) | 1.23 (0.79 -1.90 ) | 0.36 | |

| Female, White non-Hispanic | 237( 9 ) | 2410( 91 ) | 1.11 (0.72 -1.72 ) | 0.62 | |

| Age at interview | 18-29 | 195( 8 ) | 2152( 92 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| 30-39 | 225( 10 ) | 2130( 90 ) | 1.52 (1.16 -2.00 ) | <.01 | |

| 40+ | 92( 9 ) | 899( 91 ) | 1.57 (1.05 -2.34 ) | 0.03 | |

| Education | >= College graduate | 202( 7 ) | 2601( 93 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| <= High school graduate | 110( 14 ) | 704( 86 ) | 1.51 (1.16 -1.98 ) | <.01 | |

| Some college | 200( 10 ) | 1876( 90 ) | 1.12 (0.90 -1.39 ) | 0.32 | |

| Employed | Yes | 311( 7 ) | 4144( 93 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| No | 201( 16 ) | 1037( 84 ) | 2.01 (1.62 -2.51 ) | <.0001 | |

| Personal Income | $40,000+ | 97( 6 ) | 1497( 94 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| $20,000-39,999 | 112( 7 ) | 1566( 93 ) | 1.02 (0.76 -1.37 ) | 0.89 | |

| <$20,000 | 303( 13 ) | 2118( 87 ) | 1.63 (1.21 -2.20 ) | <.01 | |

| Marital status | Married/living as married | 189( 6 ) | 2734( 94 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Single | 259( 11 ) | 2088( 89 ) | 1.99 (1.58 -2.50 ) | <.0001 | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 64( 15 ) | 359( 85 ) | 2.27 (1.66 -3.11 ) | <.0001 | |

| Radiation and age at diagnosis | |||||

| Age at dx 0-4 | No RT | 53( 6 ) | 820( 94 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Cranial RT | 85( 13 ) | 587( 87 ) | 2.05 (1.41 -2.97 ) | <.001 | |

| RT other site | 43( 8 ) | 504( 92 ) | 1.57 (1.02 -2.43 ) | 0.04 | |

| Age at dx 5-9 | No RT | 28( 7 ) | 383( 93 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Cranial RT | 51( 11 ) | 430( 89 ) | 1.25 (0.76 -2.04 ) | 0.39 | |

| RT other site | 43( 12 ) | 327( 88 ) | 1.83 (1.09 -3.06 ) | 0.02 | |

| Age at dx 10-14 | No RT | 36( 10 ) | 342( 90 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Cranial RT | 26( 7 ) | 343( 93 ) | 0.58 (0.34 -1.00 ) | 0.05 | |

| RT other site | 51( 10 ) | 437( 90 ) | 1.10 (0.69 -1.75 ) | 0.69 | |

| Age at dx 15-20 | No RT | 31( 9 ) | 314( 91 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Cranial RT | 15( 8 ) | 163( 92 ) | 0.82 (0.42 -1.59 ) | 0.56 | |

| RT other site | 50( 9 ) | 531( 91 ) | 1.09 (0.67 -1.77 ) | 0.74 | |

| Chemotherapy | None | 94( 8 ) | 1045( 92 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Anthracycline/Alkylating | 310( 9 ) | 3098( 91 ) | 1.07 (0.83 -1.38 ) | 0.59 | |

| Other drugs | 108( 9 ) | 1038( 91 ) | 1.32 (0.96 -1.81 ) | 0.08 | |

| SMN | No | 465( 9 ) | 4725( 91 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Yes | 47( 9 ) | 456( 91 ) | 1.01 (0.72 -1.41 ) | 0.97 | |

| Recurrence | No | 446( 9 ) | 4676( 91 ) | 1.00 [Referent] | |

| Yes | 66( 12 ) | 505( 88 ) | 1.22 (0.91 -1.62 ) | 0.18 | |

Risk for PTSD was not significantly higher for survivors who had recurrence of their cancer (OR=1.22, 95% CI=0.72-1.41) or had a second malignant neoplasm (OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.72-1.41). In a separate multivariable model, risk for PTSD was significantly higher for survivors treated with more intensive treatment, as defined in Appendix 2 (OR=1.36, 95% CI 1.06-1.74, not shown in table).

Survivors of all diagnostic categories of cancer were at statistically significantly higher risk of PTSD compared to siblings (Table 5). Greater than 2-fold increased risks (range 2.4 to 4.6) were present for all cancer diagnostic groups.

Table 5. Risk of PTSD in survivors, by diagnosis, compared to siblings Models adjusted for demographics, personal information and intrafamily correlation.

| Type of cancer | Odds ratio (95% C.I.) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Bone cancer | 3.57 (1.56 -8.21) | <.01 |

| Central nervous system | 3.64 (1.54 -8.63) | <.01 |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 4.64 (1.91 -11.26) | <.001 |

| Kidney (Wilms) | 2.41 (1.04 -5.55) | 0.04 |

| Leukemia | 3.84 (1.74 -8.46) | <.01 |

| Non Hodgkin Lymphoma | 4.08 (1.74 -9.54) | <.01 |

| Neuroblastoma | 2.89 (1.01 -8.31) | 0.05 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 3.24 (1.42 -7.41) | <.01 |

Discussion

The prevalence of PTSD, including functional impairment and/or clinical distress as well as symptoms, was more than four times greater in young adult cancer survivors than in a comparison group of siblings. Prevalence of PTSD was associated with many of the specific demographic variables assessed, including marital status, education, employment, income and age at interview. However, the relationship of PTSD to cancer-related variables was more complex. The best predictors of risk for PTSD in the survivors were a composite variable of intensity of therapy or an interaction of age at diagnosis with cranial radiation.

Intensity of treatment, defined similarly as in this study, was not significantly correlated with PTSD in a previous study of 186 childhood cancer survivors (2). However, other studies have found that brain tumors and treatments (like cranial radiation), which have an impact on cognitive function, were associated with long term emotional distress for survivors (26-30). It may be that intensity of treatment in general, and cranial radiation in very young children in particular, is related to late effects which impair function and cause emotional distress. The association of PTSD with lower education, employment and income in survivors would be consistent with this subgroup being one with additional burdens and reminders posed by later physical and cognitive impact of cancer treatment.

The prevalence of PTSD in this study is far higher than the 3% reported by cancer survivors who were still children and adolescents (1) and is similar to, or higher than, studies that included adolescents as well as adult survivors, where an elevated rate of 10.9% (31) or a rate similar to controls (32) was reported. If the symptoms of PTSD are a result of early trauma associated with specific childhood cancer experiences, how could it be that the symptoms are not seen until people are in their thirties and forties? Because none of these prior childhood cancer studies followed survivors longitudinally through childhood and into their thirties and forties, there is no definite answer to this question. It is possible that this and other cross-sectional studies are detecting a cohort effect. For example, newer, less toxic treatments, less reliance on cranial radiation for non-CNS tumors, and better supportive care may mean that younger survivors are now less traumatized and have fewer physical and cognitive late effects than the survivors in the past. This hypothesis appears to be supported by the higher risk of PTSD associated with older age at interview in this study. However, when specifically compared on year of treatment (which was not included as an independent variable in the general analytic model due to co-variance with age at interview) there was no significant difference in risk for PTSD between survivors treated in the 1970s and those treated in the 1980s. The effects of newer treatments and supportive care in the 1990's and 21st century have yet to be explored.

Another potential explanation for the difference in prevalence of PTSD between children or adolescents and young adults is that the criteria for PTSD are more appropriate for adults than for younger individuals. However, there are many studies of adolescents exposed to a variety of traumatic events which have found that the PTSD criteria can be used with adolescents (33). A recent study found a prevalence of PTSD symptoms in adolescent recipients of solid organ transplants of 20%, much closer to that seen in the young adult studies of childhood cancer survivors than in the studies of younger cancer survivors (34). This finding suggests that child and adolescent organ transplant recipients are able to endorse symptoms of PTSD.

It may be that symptoms, clinical distress and functional impairment only emerge among the more vulnerable childhood cancer survivors as they contend with the developmental tasks of young adulthood (35) and the added challenges of late effects of treatment (29). The relative protection of the parental home is diminished as young adult survivors face the challenges of completing their education, finding a job, getting health insurance, establishing long-lasting intimate relationships, and starting a family. All of these tasks contain reminders that the survivors may be at a disadvantage relative to their peers as a result of the cancer and its treatment (e.g. due to infertility, decreased height, learning disabilities). The difficulty with developmental tasks may serve to remind the survivors of traumatic events, causing PTSD symptoms, clinical distress, or emotional impairment to surface that have been previously latent. Developmentally expected but difficult stressors (e.g. relationship difficulties, problems with school work, peer pressures, and challenges in finding and retaining employment) may overwhelm coping skills and precipitate the emergence of clinically significant symptoms.

It is not surprising, then, that lower levels of income, employment, and marriage are associated with PTSD in both the survivors and their siblings. Directionality is unclear in this association. People without the social and economic support of a job and partner are generally at greater risk for emotional distress. However, another interpretation is that PTSD is a cause or correlate of difficulty getting and keeping an education, a job or a relationship. PTSD may indicate psychological vulnerability in the survivors. As such, it may be a marker of people who are prone to other adverse life events, and a target population for mental health intervention.

Not all of those contacted for the baseline survey of this study chose to participate, and not all who were invited to participate in the psychosocial component completed these measures, suggesting that there may have been some self-selection in the respondents. Non-participants were younger at diagnosis, more likely to have had cancers of the central nervous system, more often male, younger, less well-educated, and less likely to be employed, married or making more than $20,000 a year. They were also more likely to have scores in the clinically significant range on the Brief Symptom Inventory in depression, anxiety, somatization, and global severity of emotional distress. These findings suggest that those who would appear to be at higher risk for PTSD were also less likely to participate in this study, and that the observed prevalence of PTSD in this study reflects a conservative estimate of the true population affected.

Conclusions

Although the vast majority of adult survivors of childhood cancer do not report PTSD, significantly higher rates are reported by long-term survivors compared to sibling controls. Treatment intensity appears to be a significant predictor and increased expectations for independent living of survivors as adults may exacerbate symptoms. Whatever the cause, there appears to be a group of adult survivors of childhood cancer with significant functional impairment or clinical distress and PTSD who might benefit from intervention. The next step in this line of research is to identify potential protective factors and interventions that may be used to reduce the rate of PTSD in these very long-term survivors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a collaborative, multi-institutional project, funded as a resource by the National Cancer Institute, and assembled through the efforts of 26 participating clinical research centers in the United States and Canada.

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grant U24 CA 55727 (LL Robison, Principal Investigator) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

This grant funding supported the management and analysis of the data for this manuscript, and supported the participation of Drs. Robison, Krull, Zeltzer and Mertens in the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- PTSD

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- CCSS

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

- HL

Hodgkin Lymphoma

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- NHL

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

- dx

diagnosis

- RT

radiation therapy

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

- BSI

Brief Symptom Inventory

- Rand SF-36

RAND Health Status Survey, Short Form 36

Footnotes

None of the authors have other financial interests, relationships or affiliations relevant to the subject of this manuscript which would create a potential conflict of interest for this manuscript.

Partial data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists, June 1, 2009, Orlando, Florida

References

- 1.Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Meeske K, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms, family functioning, and social support in survivors of childhood leukemia and their mothers and fathers. J Consulting and Clinical Psych. 1997;65(1):120–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuber ML, Kazak AE, Meeske K, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatrics. 1997;100(6):958–964. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobbie WL, Stuber M, Meeske K, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(24):4060–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.24.4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. IV. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meeske K, Stuber ML. PTSD, Quality of Life and Psychological outcome in young adult survivors of pediatric cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28(3):481–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(4):261–9. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YL, Santacroce SJ. Posttraumatic stress in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(8):1406–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rourke MT, Hobbie WL, Schwartz L, Kazak AE. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(2):177–82. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrag NM, McKeown RE, Jackson KL, Cuffe SP, Neuberg RW. Stress-related mental disorders in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(1):98–103. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voûte PA, de Haan RJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42(7):604–10. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–39. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute–Supported Resource for Outcome and Intervention Research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mertens AC, Walls RS, Taylor L, et al. Characteristics of childhood cancer survivors predicted their successful tracing. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:933–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Research: Experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2319–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foa EB. Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale: Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, et al. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. J Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derogatis LR. Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc.; 2000. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) 18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recklitis CJ, Parsons SK, Shih MC, et al. Factor structure of the brief symptom inventory--18 in adult survivors of childhood cancer: results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:22–32. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Feb;17(2):435–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McHorney C, Ware J, Raczek A. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (Sf-36), II: psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health conditions. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;6:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, et al. Psychological Status in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotnitzky A, Jewell NP. Hypothesis testing of regression parameters in semiparametric generalized linear models for cluster correlated data. Biometrika. 1990;77:485–97. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang KY, Zeger S. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(6):999–1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz KA, Ness KK, Whitton J, et al. Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3649–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meeske KA, Patel SK, Palmer SN, Nelson MB, Parow AM. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(3):298–305. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Packer RJ, Gurney JG, Punyko JA, et al. Long-term neurologic and neurosensory sequelae in adult survivors of a childhood brain tumor: childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Sep 1;21(17):3255–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brière ME, Scott JG, McNall-Knapp RY, Adams RL. Cognitive outcome in pediatric brain tumor survivors: delayed attention deficit at long-term follow-up. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2):337–40. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozono S, Saeki T, Mantani T, Ogata A, Okamura H, Yamawaki S. Factors related to posttraumatic stress in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(3):309–17. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerhardt CA, Yopp JM, Leininger L, et al. Brief Report: Post-traumatic Stress during emerging adulthood in survivors of pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(8):1018–23. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6(2):96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mintzer LL, Stuber ML, Seacord D, Castaneda M, Mesrkhani V, Glover D. Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Adolescent Organ Transplant Recipients. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1640–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuber ML, Shemesh E. Posttraumatic stress response to life-threatening illnesses in children and their parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(3):597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santacroce SJ, Lee YL. Uncertainty, posttraumatic stress, and health behavior in young adult childhood cancer survivors. Nurs Res. 2006;55(4):259–66. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.