Abstract

Harnessing RNA interference (RNAi) to silence aberrant gene expression is an emerging approach in cancer therapy. Selective inhibition of an overexpressed gene via RNAi requires a highly efficacious, target-specific short interfering RNA (siRNA) and a safe and efficient delivery system. We have developed siRNA constructs (UsiRNA) that contain unlocked nucleobase analogs (UNA) targeting survivin and polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) genes. UsiRNAs were encapsulated into dialkylated amino acid-based liposomes (DiLA2) containing a nor-arginine head group, cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHEMS), cholesterol and 1, 2-dimyristoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-polyethyleneglycol 2000 (DMPE-PEG2000). In an orthotopic bladder cancer mouse model, intravesical treatment with survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes at 1.0 and 0.5 mg/kg resulted in 90% and 70% inhibition of survivin or PLK1 mRNA, respectively. This correlated with a dose-dependent decrease in tumor volumes which was sustained over a 3-week period. Silencing of survivin and PLK1 mRNA was confirmed to be RNA-induced silencing complex mediated as specific cleavage products were detected in bladder tumors over the duration of the study. This report suggests that intravesical instillation of survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA can serve as a potential therapeutic modality for treatment of bladder cancer.

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) involves the use of short double-stranded RNAs (siRNAs) to promote sequence-specific degradation of target mRNA. In the last decade, RNAi has been exploited as an experimental tool for elucidation of gene function, and is being developed as a new therapeutic platform for incurable diseases such as cancer.

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the western world, with an estimated 68,000 newly detected cases in the United States in 2008.1,2 About 70% of the newly diagnosed bladder cancer patients have nonmuscle invasive disease in which the papillary tumor invades the urothelium (Ta) and lamina propria (T1), or carcinoma in situ with a relatively flat tumor within the urothelium.1,2 Current standard of care to treat or prevent recurrence of nonmuscle invasive bladder tumors in high-risk patients includes transurethral resection, followed by immunotherapy using Bacillus Calmette-Guerin or chemotherapy with mitomycin C, doxorubicin, or thiotepa instilled intravesically into the bladder. However, morbidity associated with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin intolerance or resistance to immunotherapy or chemotherapy can often lead to recurrence. Additional alternative therapies are needed to prevent recurrence or progression to a highly muscle invasive and often lethal bladder carcinoma.2,3,4 In recent years, antisense oligonucleotides (AS-ODN) and siRNAs against numerous genes that deregulate cellular homeostasis have been explored for the treatment of bladder cancer.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Preclinical studies targeting genes involved in antiapoptosis (Bcl-2, clusterin, Bcl-xl, XIAP, survivin, Hsp27), oncogenesis (Hras and c-myc), angiogenesis (FGFR and VEGF), cell cycle regulation (polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1), Ki-67, telomerase, and telomerase reverse transcriptase) and growth factors (transforming growth factor-β, protein kinase Cα, EPHB4) have shown some promise in tumor growth inhibition.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 We investigated two bladder cancer-specific genes, survivin and PLK1 as potential siRNA therapeutics against bladder cancer. Survivin plays an important role in suppression of apoptosis and regulation of cell division. It enables the antiapoptotic pathway to block cell death by interacting directly or indirectly with caspases, the downstream effector molecules in apoptosis pathway. Survivin is often upregulated in G2M phase of cell cycle and localizes to various components of mitotic apparatus such as centrosomes, and metaphase and anaphase spindle microtubules.18,19,20 Selective overexpression of survivin has been documented in a wide variety of cancer cell types including bladder cancer.18,19,20 Downregulation of survivin mRNA has been associated with decreased tumor growth and sensitization to radiation and chemotherapeutic agents. Low survivin expression in normal cells also makes it an attractive target for bladder cancer.5,10,19,20,21,22,23

PLK1 is a cell cycle-regulated kinase whose expression peaks during G2M phase of cell cycle and transiently associates with spindle apparatus and centromere region of mitotic chromosomes. It is often deregulated and overexpressed in tumor cells. RNAi-mediated depletion of PLK1 mRNA can lead to cell cycle arrest, growth inhibition and apoptosis in cancer cells.17,24,25,26

In the present study, we describe the development of DiLA2 liposome formulated survivin and PLK1 targeting UsiRNAs as therapeutics against bladder cancer. UsiRNAs were modified with non-nucleotide, acyclic monomers previously shown to provide several advantages for siRNA function.27,28,29 The UsiRNAs were encapsulated in DiLA2-based liposomes containing a nor-arginine head group, CHEMS, cholesterol, and DMPE-PEG2000 delivered locally to bladder tumors via intravesical instillation. Our results suggest that downregulation of survivin and PLK1 may be effective in inhibition of tumor growth and progression of bladder carcinomas.

Results

In vitro RNAi activity of survivin and PLK1 UsiRNAs

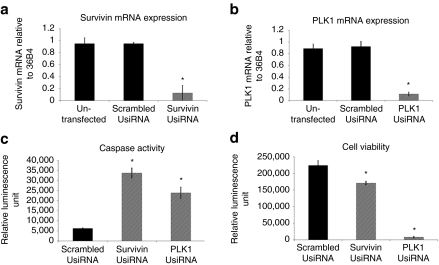

We screened a panel of 25–30 UsiRNAs targeting human survivin and PLK1 mRNA in three representative bladder cancer cell lines, KU-7-luc (a luciferase-tagged human bladder cancer cell line), UM-UC3, and T24. Most UsiRNAs exhibited mRNA reduction of >90% relative to scrambled UsiRNA at concentrations of 25 and 5 nmol/l in all tested cell lines (Figure 1a,b). Lead survivin and PLK1 UsiRNAs had IC50 values of 29 and 10 pmol/l in KU-7-luc cells, respectively (data not shown). We next evaluated the effects of survivin or PLK1 mRNA depletion on cell viability and apoptosis. Microscopic examination and cell viability assays with survivin UsiRNA transfected KU-7-luc cells showed 40% inhibition in cell growth observed at 96 hours post-transfection. In addition, suppression of survivin mRNA also led to approximately seven- to eightfold increases in caspases 3/7 activities at 96 hours post-transfection. In contrast, depletion of PLK1 mRNA in bladder cancer cells demonstrated a 95% growth inhibition and a fivefold induction of apoptosis as early as 48 hours post-transfection (Figure 1c,d).

Figure 1.

Effect of survivin UsiRNA or polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) UsiRNA on mRNA expression, apoptosis, and cell growth. KU-7-luc cells were transfected with 5 nmol/l survivin UsiRNA, PLK1 UsiRNA, or scrambled survivin UsiRNA and assayed for mRNA expression using quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR. Knockdown of (a) survivin mRNA or (b) PLK1 mRNA, as normalized to 36B4; scrambled survivin UsiRNA and untransfected cells served as negative controls. (c) Induction of apoptosis in survivin, PLK1, or scrambled survivin UsiRNA-treated cells at 96 hours post-transfection, as measured by Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay. (d) Decrease in cell viability in survivin, PLK1, or scrambled survivin UsiRNA-treated cells at 96 hours post-transfection, as measured by Cell-Titer-Glo viability assay. N = 3 per group; Mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 suggesting statistical significance of UsiRNA-treated group as compared to scrambled control.

In vivo tumor growth inhibition with survivin and PLK1 UsiRNAs

To achieve effective intravesical delivery of UsiRNA into mouse bladder, we formulated survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA in DiLA2-based liposomes containing a nor-arginine head group containing C18:1-norArg-C16 (Supplementary Figure S1), CHEMS, cholesterol, and DMPE-PEG2000 at molar ratios of 45:28:25:2 mol%. The mean particle size of the liposomes was estimated to be 125 nm with a low polydispersity range of 0.10–0.15. Dye measured siRNA encapsulation ranged from 75 to 90% as measured by SYBR Gold assay. Liposomes were positively charged at pH 7.4 with a zeta-potential of 10–12 mV with a shift to higher positive charge at pH 4.0 with a zeta-potential of 30–35 mV.

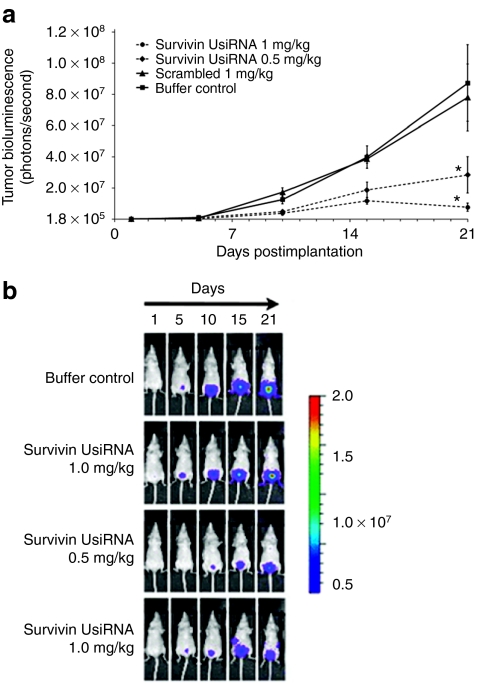

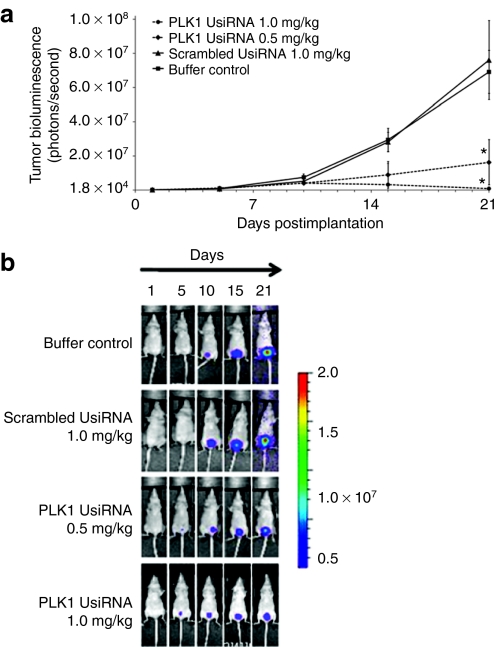

We then investigated the biodistribution of survivin UsiRNA encapsulated in DiLA2 liposomes after intravesical instillation into mouse bladder using a dual-probe hybridization assay. Approximately 25% of the input survivin UsiRNA was detected in the bladder tissue at 30 minutes postdose. These levels decreased to about 5% input dose by 1 hour and were sustained at this level for 24 hours post-instillation (Supplementary Figure S2). To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of DiLA2 liposome-formulated survivin, PLK1, or scrambled UsiRNA, mice-bearing KU-7-luc-derived orthotopic bladder tumors were dosed intravesically at 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg at days 2, 4, and 7, 9 post-tumor implantation. Tumor growth was monitored by visualizing the bioluminescence emitted from the luciferase-tagged tumors for 21 days using a whole body imaging system. Survivin UsiRNA elicited dose-dependent decrease in tumor volumes of tenfold and fivefold at 1.0 and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 2a,b). PLK1 UsiRNA demonstrated a maximal growth inhibition of 68-fold at 1.0 mg/kg. The lower dose of 0.5 mg/kg provided a fivefold suppression in tumor volumes relative to buffer control (Figure 3a,b). In contrast, scrambled UsiRNA-treated animals showed tumor progression kinetics similar to buffer-treated control animals. Mice exhibited no change in body weights or hematuria postadministration suggesting that DiLA2-based liposome delivery was well tolerated.

Figure 2.

Tumor growth kinetics of bladder tumors treated intravesically with DiLA2 liposome-encapsulated survivin UsiRNA in an orthotopic bladder cancer mouse model. KU-7-luc-derived tumors in nude mice (n = 8) were treated with survivin UsiRNA at 1.0 or 0.5 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg scrambled (control) UsiRNA at days 2, 4, 7, and 9 postimplantation. Tumor bioluminescence was measured at day 1 (randomization day) and days 5, 10, 15, and 21 via an IVIS200 whole body imaging system. Buffer-treated mice served as control group. *P < 0.05 suggesting statistical significance of survivin UsiRNA-treated group as compared to buffer control. (a) Group mean ± SE tumor bioluminescence measured as photons/second (b) bioluminescence images of representative mice in each treatment group.

Figure 3.

Tumor growth kinetics of bladder tumors treated intravesically with DiLA2 liposome-encapsulated polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) UsiRNA in an orthotopic bladder cancer mouse model. KU-7-luc derived tumors in nude mice (n = 8) were treated with PLK1 UsiRNA at 1.0 or 0.5 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg scrambled (control) UsiRNA at days 2, 4, 7, and 9 postimplantation. Tumors were monitored for bioluminescence at day 1 (randomization day) and days 5, 10, 15, and 21 via an IVIS200 whole body imaging system. Buffer-treated mice served as control group. *P < 0.05 suggesting statistical significance of PLK1 UsiRNA-treated group as compared to buffer control. (a) Group mean ± SE tumor bioluminescence measured as photons/second (b) bioluminescence images of representative mice in each group.

In vivo RNAi activity of survivin and PLK1 UsiRNA

Human survivin and PLK1 mRNA expression was measured from total bladder RNA harvested at day 21. Survivin UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes demonstrated ~90% and 60% mRNA inhibition at 1.0 and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 4a). Similarly, DiLA2 liposome-encapsulated PLK1 UsiRNA provided mRNA knockdown of ~95% and 70% at 1.0 and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 4b). The DiLA2/scrambled UsiRNA-treated mice exhibited no nonspecific decrease of survivin or PLK1 mRNA relative to buffer control. Naked survivin UsiRNA-treated bladder tumors also elicited no decrease in survivin mRNA expression relative to buffer control (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 4.

DiLA2 liposome-encapsulated survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA-mediated gene silencing in bladder tumors. Bladders from tumor-bearing mice treated with survivin UsiRNA or polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) UsiRNA at 1.0 and 0.5 mg/kg at days 2, 4, 5, and 9 were analyzed for reduction in (a) survivin or (b) PLK1 mRNA expression at day 21 using quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR. Survivin or PLK1 mRNA-levels were normalized to housekeeping genes HPRT1, HSPCB, and TBP and expressed relative to buffer-treated control using a relative quantification method. Values are represented as group mean ± SE, n = 4 per time-point. *P < 0.05 suggesting statistical significance of UsiRNA-treated groups as compared to buffer control.

Survivin and PLK1 UsiRNAs have cross-species homology to human and mouse genes except for a single-nucleotide mismatch to mouse survivin. Silencing of mouse-specific survivin and PLK1 mRNA expression was evaluated in a quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay using mouse-specific survivin and PLK1 primers. No suppression in mouse survivin and PLK1 mRNA expression relative to buffer control was noted (data not shown). To rule out the possibility of immune stimulation driving mRNA and tumor growth inhibition, we analyzed mRNA expression of two interferon-inducible genes, IFIT1 and OAS1a, in survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA-treated mouse bladders collected at days 5, 10, 15, and 21 postdose. No alterations in IFIT1 or OAS1a mRNA in UsiRNA-treated mice were detected, suggesting cytokine induction was not responsible for the observed effects (data not shown).

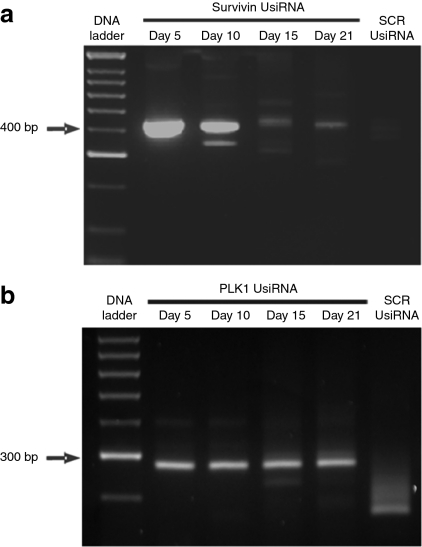

Confirmation of RNAi activity with 5′ RACE-PCR

To demonstrate that the silencing observed in survivin- and PLK1 UsiRNA-treated bladders was induced by an RNAi mechanism, rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) analysis was performed. 5′ RACE-PCR analysis of total RNA using human survivin gene-specific primers identified a PCR product of expected molecular size ~400 bp in survivin UsiRNA-treated bladder tumors. This band was not observed in scrambled control-treated RNA samples. 5′RACE-PCR performed on PLK1 UsiRNA-treated bladder tumors also amplified the predicted sized cleavage product of ~300 bp that was specific to PLK1 UsiRNA treatment group. Both survivin and PLK1 UsiRNA-mediated mRNA cleavage products were identifiable at days 5, 10, 15, and day 21 postimplantation which corresponded to 12 days after the last treatment (Figure 5a,b). These results indicate a sustained, sequence-specific, RNA-induced silencing complex mediated activity in bladder tumors treated with DiLA2 liposome formulated UsiRNAs (Supplementary Figure S4a,b).

Figure 5.

Confirmation of RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated mechanism of action with survivin and polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) UsiRNAs in bladder tumors through day 21. A 2% agarose gel showing 400 or 300 bp RNA-induced silencing complex RISC-mediated cleavage product for survivin UsiRNA or PLK1 UsiRNA-treated RNA samples, respectively. (a) Treatment groups include survivin UsiRNA or a nonspecific scrambled control UsiRNA formulated in DiLA2 liposomes. First lane: 100-bp DNA ladder; second to fifth lanes, survivin UsiRNA-treated bladder tissue harvested at days 5, 10, 15, and 21; last lane, scrambled control (SCR) UsiRNA-treated mouse bladder at day 10. (b) Treatment groups include PLK1 UsiRNA or a nonspecific scrambled control siRNA formulated in DiLA2 liposomes. First lane: 100-bp DNA ladder; second to fifth lanes, PLK1 UsiRNA-treated bladder harvested at days 5, 10, 15, and 21; last lane, scrambled control (SCR) UsiRNA-treated mouse bladder at day 10.

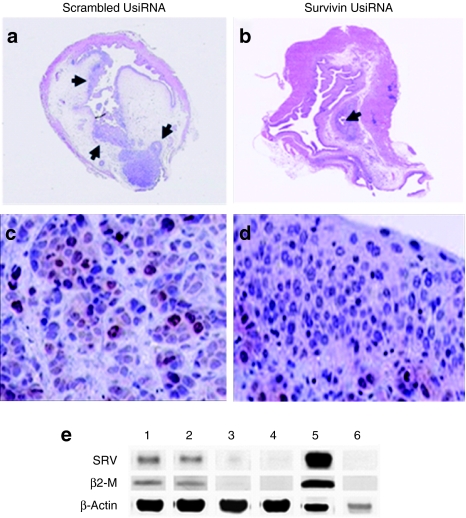

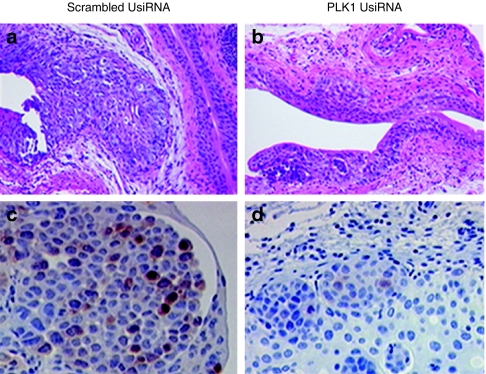

Immunohistochemical and western blot analysis of UsiRNA-treated bladder tissue demonstrated significant downregulation of survivin and PLK1 protein levels (Figures 6a–e and 7a–d). The reduction in PLK1 protein was markedly more pronounced than that of survivin protein. These data, plus the greater tumor growth inhibition mediated by PLK1 UsiRNA suggests that PLK1 may be more effective than survivin as a target for bladder cancer treatment.

Figure 6.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry of survivin protein in bladder tumors from control and survivin UsiRNA-treated mice. Representative images from the bladder treated with scrambled survivin UsiRNA or survivin UsiRNA formulated in DiLA2 liposomes. (a,b) H&E-stained whole bladder tissue; arrows indicate the presence of tumor within the mouse bladder. Immunostained sections of bladder tumor using antisurvivin protein monoclonal antibodies from (c) 1.0 mg/kg scrambled UsiRNA or (d) 1.0 mg/kg survivin UsiRNA-treated bladder tissues. (e) Western blot analysis. Survivin protein was detected using antibodies to human-specific survivin, human-specific β2-microglobulin as human housekeeping control and human/mouse crossreactive anti-β-actin served as loading control. Lane 1: buffer control; lane 2: scrambled control UsiRNA 1.0 mg/kg; lane 3: survivin UsiRNA 0.5 mg/kg; lane 4: survivin UsiRNA 1.0 mg/kg; lane 5: KU-7-luc cell lysate; lane 6: untreated mouse bladder. Magnification, ×1.25 for whole bladder H&E staining and ×20 for survivin immunohistochemistry.

Figure 7.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry of polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) protein in bladder tumors from control and PLK1 UsiRNA-treated mice. Representative images from the bladder of mice treated with scrambled survivin UsiRNA or PLK1 UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes. (a,b) H&E-stained sections and (c,d) immuno-stained sections using anti-PLK1 monoclonal antibodies from scrambled UsiRNA or PLK1 UsiRNA-treated mice, respectively. Magnification, ×10 for H&E staining and ×20 for PLK1 protein immunohistochemistry.

Discussion

Dis-regulated gene expression leading to uncontrolled cellular growth and genomic instability are hallmarks of cancer. Abrogating the abnormal expression of aberrant genes via RNAi provides a rational approach to cancer therapeutics. To provide a specific RNAi-based therapeutic approach against bladder cancer, we explored survivin and PLK1 genes as potential targets. Survivin and PLK1 have been documented to be selectively overexpressed in most bladder tumors and are often considered prognostic biomarkers for many cancers including bladder cancer.18,24,25,30,31,32,33 Downregulation of survivin with AS-ODN or siRNAs led to impairment of cell growth by 30–50% and induction of apoptosis by twofold compared to control-treated group.5,7,8,23 Knockdown of survivin with siRNA or AS-ODN restored bladder cancer cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents by inducing a pronounced apoptotic effect.21 In addition, Nogawa et al.14 described PLK1 siRNAs that mediated a decrease in cell viability in eight cell lines representing various grades of bladder cancer. It was also shown that intravesical treatment of orthotopic bladder tumors with PLK1 siRNA encapsulated in cationic liposomes dosed at 600 nmol/l and 6 µmol/l, at days 5–9 post-tumor implantation provided approximately tenfold inhibition in tumor growth compared to control siRNA. Histopathological examination of treated bladder tissues showed absence of tumor cells in two out of seven animals.14 Another study using cationic liposome-encapsulating plasmids expressing interferon-α1 and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor also demonstrated significant tumor growth inhibition and 70–80% survival benefit relative to control group.6,12

We identified survivin and PLK1 UsiRNAs that caused induction of apoptosis and significant inhibition of cell growth in KU-7-luc, T24, and UM-UC3 cells in vitro. PLK1 UsiRNA appeared to be more cytotoxic than survivin UsiRNA in most bladder cancer cell lines. Also, in comparison to survivin UsiRNA, PLK1 UsiRNA exhibited a remarkable decline in cell growth and density with induction of apoptosis by 48 hours post-transfection. The lead UsiRNAs were then evaluated for mRNA and tumor reduction in an orthotopic bladder cancer mouse model.

Delivery of UsiRNA into bladder urothelium was achieved by encapsulating UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes as survivin UiRNA alone yielded no RNAi effect in bladder tumors. Similarly, Nogawa et al. observed no siRNA uptake in mouse bladders with intravesical administration of naked siRNA at low-dose levels.14 UsiRNAs were encapsulated into liposomes using dialkylated nor-arginine, CHEMS, cholesterol, and DMPE-PEG2000 to produce ~100 nm, multilamellar liposomal particles with >90% encapsulation efficiency. Intravesical treatment with these liposomes resulted in significant reduction in tumor volumes that were sustained for at least 12 days after the last dose. The extent of tumor reduction was more pronounced in the PLK1 UsiRNA-treated animals with ~68-fold reduction as compared to a tenfold decrease observed with survivin UsiRNA. Similarly, the mRNA downregulation was found to be greater with PLK1 UsiRNA in comparison to survivin UsiRNA treatment. The presence of sequence-specific 5′ RACE-PCR cleavage products at day 21 also confirmed a sustained RNAi-mediated mechanism of action up to 12 days after the last dose.

Similar to mRNA inhibition, reduction of PLK1 protein expression was also more pronounced compared to the modest decrease observed in survivin protein. This difference in tumor response with survivin and PLK1 UsiRNAs could be attributable to the different cell cycle pathways controlled by PLK1 and survivin. PLK1 has been shown to regulate the progression of G2 to M phase of cell cycle and consequently its downregulation via RNAi would have a stronger inhibition effect on cell growth. In contrast, survivin interacts with caspases, the effector proteins of the apoptotic pathway. Depletion of survivin can potentially maintain cells in growth arrest before initiating the process of cell death. As a result, a modest decrease in cell viability and tumor growth might be expected after treatment with survivin UsiRNA.

We employed intravesical instillation as a nonsystemic delivery option for RNAi-based treatment for bladder cancer. Intravesical delivery is an attractive delivery approach with several advantages. Normal urothelium provides a relatively tight barrier between blood and urine that can prevent or reduce the absorption of siRNAs from the bladder into systemic circulation, thereby limiting any potential toxicity.4,34 Direct instillation of UsiRNAs into the bladder cavity also provides maximal exposure to tumors in the urothelium.

Activation of the innate immune system can lead to a nonspecific silencing of genes through recruitment of TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8 pathways.35,36,37,38 A recent report suggested that the antitumor effects of a nontargeting siRNA on melanoma resulted from activation of the RIG-I pathway.39 However, in the present study, no upregulation of interferon-inducible genes IFIT1 and OAS1a was detected after treatment with DiLA2-encapsulated UsiRNAs. This observation further supports the conclusion that abrogation in mRNA expression and tumor growth in bladder tissue occurred via a target-specific RNAi-mediated pathway.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that intravesical administration of survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA formulated in DiLA2-based liposomal delivery vehicles can potentially serve as a therapeutic approach for bladder cancer. UsiRNA treatment resulted in target-specific downregulation of survivin or PLK1 mRNA expression and suppressed the growth of bladder tumor cells in a dose-dependent manner. Because survivin and PLK1 have been shown to regulate different cellular pathways, a combination of survivin and PLK1 UsiRNA for a more pronounced additive or synergistic effect on tumor growth inhibition is under investigation. Furthermore, UsiRNAs could potentially be combined with existing chemotherapeutic agents to enhance the chemosensitivity of bladder cancer cells in refractory bladder carcinomas. Future work includes screening additional genes to target critical cancer phenotypes for enhanced efficacy and prolonged therapeutic effect against transitional cell bladder carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

siRNA. Human-specific survivin (GenBank accession number NM_001012271) and PLK1 siRNAs (GenBank accession number NM_005030) were designed using proprietary siRNA design algorithm. Chemical synthesis of each UsiRNA was performed using standard RNA oligo synthesis chemistry with the inclusion of unlocked nucleobase analogs (UNA) at the 3′ termini of passenger and guide strands and an additional UNA at the 5′ end of the passenger strand.27,28,40,41 The sequence of the UsiRNA passenger strands were: survivin siRNA modified with UNA at the 3′ end of both strands, 5′- CCAGUGUUUCUUCUGCUUCunaUunaU; PLK1 siRNA modified with UNA at the 3′ termini and 5′ end of the passenger strand (P-1), 5′unaUAGAAGAUGCUU CAGACA GAunaUunaU; scrambled control, 5′-UCCCGUUCUAGUGUUUCCUunaUunaU. UsiRNAs were synthesized at Marina Biotech (Bothell, WA).

Synthesis of C18:1-norArg-C16 (palmityl oleoyl nor-arginine). Starting materials and reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Solvents for isolation and chromatography were reagent grade, solvents for reactions were dried. Thin layer chromatography was performed using precoated aluminum thin layer chromatography sheets (silica gel 60 F254). Column chromatography was performed using TELEDYNE Isco CombiFlash Instrument and normal phase silica gel. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on 400 MHz JEOL ECX-400 spectrometer with TMS as an internal standard. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-UV/MS were obtained on a Waters 2795 (HPLC) and carried out on Agilent Eclipse XDB-C8 column eluted with 2–98% of mobile phase B [A: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in IPA/water/MeOH (15:30:55); B: 0.1% TFA in IPA/MeOH (30:70)], flow rate 1 ml/minute, 20 minutes, 60 °C. Purity of compounds was determined by HPLC-ELS, obtained on Waters 2695 (HPLC) instrument and carried out on YMC-Pro C18 reverse-phase column eluted with 20–100% mobile phase B [A: 0.1% TFA in IPA/water/MeOH (15:30:55); B: 0.1% TFA in IPA/MeOH (30:70)], flow rate 0.3 ml/minute, 40 minutes, 60 °C.

To a suspension of N-α-Fmoc-N-γ-Boc--2,4-diaminobutyric acid in dichloromethane (DCM) two equivalents of diisopropylethyl amine were added. The resulting mixture was added to 2-chlorotrityl choride resin, agitated for 2 hours at room temperature and the solvent was removed by filtration. DCM/MeOH/diisopropylethyl amine (85:10:5 vol/vol) was added to the resin and the mixture was agitated for further 30 minutes at room temperature. The resin was filtered and washed three times with dimethylformamide. The Fmoc group was removed by treating the resin with 20% piperidine in dimethylformamide and agitation for 20 minutes at room temperature providing free α-amine (positive Kaiser test). Oleic acid was preactivated with 2-(6-chloro-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HCTU) and two equivalents of diisopropylethyl amine, and added to the resin. The mixture was agitated for 1 hour at room temperature and deemed complete by negative Kaiser test. Solvent was removed by filtration, the resin washed with DCM and the desired compound was cleaved from the resin by multiple treatments with 1% TFA in DCM followed by evaporation under reduced pressure providing free carboxylate intermediate. The second alkyl chain was attached by preactivating the free carboxyl group with 1-ethyl-3-(3′-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride and N-hydroxybenzotriazole monohydrate in a 1:1 mixture of dimethylformamide and DCM for 10 minutes followed by addition of hexadecyl amine in same solvent and subsequent stirring for 30 minutes at room temperature. Excess of hexadecylamine was removed by treatment with Amberlite IR 120 hydrogen form cation exchange resin (Dow, Midland, MI) and crude compound was purified by flash chromatography. The pure dialkylated intermediate was dissolved in 1 mol/l HCl/ethyl acetate solution and the α-Boc group was removed within 1 hour followed by removal of the solvent under reduced pressure. The resulting white solid was taken up in DCM to which triethylamine was added to facilitate dissolution followed by treatment with 1,3-di-Boc-2-(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)guanidine for 1 hour. Upon completion of the reaction, the mixture was washed with 2 mol/l sodium bisulfate, saturated sodium bicarbonate and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the residue dissolved in absolute ethanol and added drop wise to 12 N HCl to remove two Boc groups. The final product precipitated during reaction and was recrystallized from EtOH and lyophilized providing C18:1-norArg-C16 as white solid, Rf = 0.25 [DCM/MeOH (90:10), iodine vapor exposure]. 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) Δ 5.34 (m, 2H), 4.37 (q, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.17–3.34 (m, 4H), 2.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.02–2.10 (m, 6H), 1.83–1.90 (m, 1H), 1.61–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.48–1.52 (m, 6H), 1.28–1.33 (m, 46H), 0.90 (t, J = 6.8, 6H). 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) Δ 176.53, 173.39, 158.73, 130.92, 130.80, 52.17, 40.51, 39.40, 36.85, 33.11, 32.34, 30.84–30.32 (18 C), 28.22, 28.19, 28.00, 26.91, 23.78, 14.51. HPLC-UV/MS: Rt 14.27 minutes (TIC) (2–98%, 20 minutes), m/z 649 for [M+H]+ (calculated 648.06 for C39H77N5O2). HPLC-ELS: Rt 20.829 minutes (99.47%). The generic structure of a guanidinium-based DiLA2 molecule is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. HPLC chromatograms are shown in Supplementary Figures S5 and S6.

DiLA2-based liposomes. C18:1-norarg-C16 or palmitoyl oleoyl nor-arginine was synthesized at Marina Biotech as described above. C18:1-norarg-C16 was selected from a panel of arginine-based DiLA2 molecules as the guanidinium head group is known to interact strongly with the negatively charged proteoglycans on the cell surface. Cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHEMS) and cholesterol were obtained from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). 1, 2-dimyristoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-polyethyleneglycol 2000 (DMPE-PEG2000) was obtained from Genzyme (Boston, MA). DiLA2-based liposomes were prepared using an impinging stream process (R.C. Adami, S. Seth, P. Harvie, R. Johns, R. Fam, K. Fosnaugh et al., manuscript in preparation). Briefly, separate stock solutions were prepared consisting of 45 mol% C18:1-norarg-C16, 28 mol % CHEMS, 25 mol% cholesterol, and 2 mol% DMPE-PEG2K, 24 mmol/l total concentration in ethanol, and UsiRNA in 215 mmol/l sucrose, 20 mmol/l phosphate, pH 7.4 (SUP buffer). The two solution streams were impinged to form liposomes which were subsequently incubated for 1 hour followed by reduction of ethanol to 10%. Ethanol was removed and liposomes concentrated using tangential flow filtration on a PES 100 kDa membrane (Sartorius Vivaflow 50). Dosing solutions were filtered through 0.22 micron membranes and stored frozen in vials at −80 °C. The UsiRNA encapsulated DiLA2-based liposome solutions were diluted to the appropriate UsiRNA concentration using SUP buffer. Particle size and zeta-potential of the liposomes were determined using a Malvern Nano ZS particle sizer (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). Nucleic acid encapsulation efficiency was measured using the SYBR Gold assay based on manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro efficacy and cell growth inhibition with survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA. Human bladder cancer cell lines T24 and UM-UC3 were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). KU-7-luc was provided by Dr A.S. (The Prostate Center, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 5% (wt/vol) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were reverse transfected with survivin, PLK1, or scrambled control UsiRNAs at a concentration of 5 nmol/l using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). The cell density was maintained at 10,000 cells per well for 24 hours endpoints, and 3,750 cells/well for time-points over 48 hours endpoints in a 96-well format. At 24 hours post-transfection, 100 µl of 20% serum-containing medium was added such that the final concentration of serum was 10%. At 24 hours post-transfection, mRNA was extracted from lysed cells and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assays were performed to quantitate the expression of survivin or PLK1 mRNA-levels. GAPDH or 36B4 served as the housekeeping genes for subsequent normalization to assess RNAi activity. Primers for survivin were survivin-F: 5′-ATCAAGAGGGGCATCATTTCT-3′ and survivin-R: 5′-GAGTGGAGCAGTTTCCATACAC-3′ PLK1-F: 5′-CGAGTTATTCATCGAGACCTCA-3′ and PLK1-R: 5′-TGGTTGCCAGTCCAAAATC-3′ housekeeping gene 36B4-F: 5′-TCTATCATCAACGGGTACAAACGA-3′ and 36B4-R: 5′-CTTTTCAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTG-3′.

Cell viability (Cell-Titer-Glo; Promega, Madison, WI) and caspase induction (Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent; Promega) were measured at various time-points up to 96 hours post-transfection to assess effects on cell viability and apoptosis, respectively.

Intravesical dosing of mice. Eight-week-old female athymic Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were anaesthetized with 1.75% isoflurane in preparation for implantation with KU-7-luc cells as described previously.13,42 A superficial 6/0 silk purse-string suture was placed around the urethral meatus before a 24-gauge lubricated catheter was inserted through the urethra into the bladder. Upon washing the bladder once with phosphate-buffered saline, ~2 million KU-7-luc cells in 50 µl were instilled into the bladder and a suture placed to occlude the urethra for 2 hours. At 1 day postimplantation, tumor growth was confirmed by bioluminescence (IVIS200 Imaging System; Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) and mice were randomized into treatment groups. KU-7-luc-bearing mice were treated with DiLA2-formulated UsiRNAs targeting survivin and PLK1. Intravesical dosing was performed twice weekly at days 2, 4, 7, and 10 post-tumor implantation. Tumor progression (n = 8) was examined by injecting 150 mg/kg luciferin intraperitoneally in the supine position and imaged at days 5, 10, 15, and 21 postimplantation using the IVIS 200 imaging system. All animal studies were carried out at The Prostate Center, University of British Columbia using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of British Columbia.

In vivo efficacy with survivin or PLK1 UsiRNAs. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with DiLA2 liposomes encapsulating survivin or PLK1 UsiRNAs at 0.5 and 1 mg/kg, or scrambled control UsiRNA at 1.0 mg/kg. Bladders (n = 4) were harvested at various time-points postdose and homogenized in lysis buffer using FastPrep-24 sample preparation system (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Total RNA was extracted from tissue homogenates using the Invitrogen PURE Link 96 RNA Isolation Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was isolated and then quantified using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and qualitatively analyzed for RNA integrity using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Total RNA (1 µg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out in a 384-well format to detect survivin or PLK1 expression levels using the Quanta Perfecta SYBR Green Fast Mix with ROX (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD), on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT platform (Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method in qBASE relative quantification software (Biogazelle, Ghent, Belgium). Endogenous housekeeping genes, HPRT1, HSPCB, and TBP were selected based on geNorm analysis (http://medgen.ugent.be/~jvdesomp/genorm). The Qbase software calculates the target mRNA-levels by normalization to the geometric mean of the above mentioned housekeeping genes according to the formula: 2(CTTarget −CTHKG), where CT is the threshold cycle. Relative mRNA-levels using two human-specific survivin or PLK1 primers were normalized against housekeeping genes, and the fold change in mRNA-levels was ascertained for the UsiRNA-treated group normalized to the buffer-treated control group.

Human-specific survivin primers were survivin-F: 5′-TCCGGTTGCGCTTTCCT-3′ and survivin-R: 5′-TCTTCTTATTGTTGGTTTCCTTTGC -3′ human-specific PLK1 primers were PLK1-F: 5′-CTCAACACGCCTCATCCTC and PLK1-R: 5′-GTGCTCGCTCATGTAATTGC-3′ mouse-specific survivin primers were survivin-F: 5′-TCTGGCAGCTGTACCTCAAGAACT-3′and survivin-R: 5′-AAACACTGGGCCAAATCAGGCT-3′ mouse-specific PLK1 primers were PLK1-F: 5′-TGAGTGCCACCTTAGTGACTTGCT-3′ and PLK1-R: 5′-ACACAGCTGATACCCAAGGCCATA-3′. Housekeeping gene primers were HPRT1-F: 5′-TGACACTGGCAAAACAATGCA and HPRT1-R: 5′-GGTCCTTTTCACCAGCAAGCT-3′ HSPCB-F: 5′-AAGAGAGCAAGGCAAAGTTTGAG-3′and HSPCB-R: 5′-TGGTCACAATGCAGCAAGGT-3′ TBP-F: 5′-TGCACAGGAGCCAAGAGTGAA-3′ and TBP-R: 5′-CACATCACAGCTCCCCACCA-3′.

Bladders collected at various time-points postdose were also examined for immune stimulation by assaying for interferon-inducible genes IFIT1 and OAS1a using real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. IFIT1 primers were IFIT1-F: 5′-CCAAGTGTTCCAATGCTCCT-3′ and IFIT1-R: 5′-GGATGGAATTGCCTGCTAGA-3′ OAS1a primers were OAS1a-F: 5′-CTTTGATGTCCTGGGTCATGT-3′ and OAS1a-R: 5′-GCTCCGTGAAGCAGGTAG-3′.

5′ RACE assay. Total RNA was isolated from ~50 to 100 mg mouse bladder tissues using the Trizol RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen) followed by phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol extraction and DNase treatment (Turbo DNase; Invitrogen) to remove contaminating proteins and DNA, respectively. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using a gene-specific primer (survivin GSP: 5′-AGGGACTCTGTCTCCATTCTCTCAT-3′ PLK1 GSP: 5′-GAGCGTGAGCTCAGCAGCTTGTC-3′) and reverse transcriptase Superscript TM II (Invitrogen). The original RNA was removed from the duplex by treatment with RNase H followed by purification using a SNAP column. To PCR-amplify the specific cleavage product, a homopolymeric tail was added to the 3′ end of the cDNA and two rounds of PCR amplification were carried out using GSP1 (survivin GSP1: 5′-CACCCGCTGCACAGGCAGAA-3′ PLK1 GSP1: 5′-CACGCTGTTATCACAGAGCTG-3′) and deoxyinosine-containing anchor primer, and nested PCR with the gene-specific primer GSP2 (survivin GSP2: 5′-TCTGGGACCAGGCAGCTCCG-3′ PLK1 GSP2: 5′-AGGGCTTGGAGGCATTGACAC-3′) and the adaptor primer. PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting. Protein samples from bladder tissues were isolated from the organic phase of Trizol homogenates using manufacturer's protocol, except that proteins were precipitated with three volumes of acetone, and the final washed pellets were resuspended in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 63 mmol/l Sarkosyl, 1 mmol/l DTT, 50 mmol/l Tris, pH 9.0.43 Equivalent protein amounts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 4–12% Bis–Tris gels in MES buffer, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for western analysis. Proteins isolated from Trizol extracts of monolayer-cultured KU-7-luc cells and untreated mouse bladders served as positive and negative controls, respectively. The nitrocellulose membranes were blocked using 0.5% heat-denatured bovin serum albumin/0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline, incubated with human-specific survivin antibodies (1:1,000 dilution of rabbit mAb, clone 71G4B7; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), human-specific β2-microglobulin (1:200 dilution, clone HYB290-03; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), antiactin antibodies (1:4,000 dilution, clone AC-74; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) followed by goat anti-mouse IRDye680 and goat anti-rabbit IRDYe800CW secondary antibodies (LICOR, Lincoln, NE). Reactive bands were visualized in the near-infrared range with the LICOR Odyssey scanner and quantitated using LICOR software.

Immunohistochemical staining of bladder tissue. Bladders from UsiRNA-treated and buffer-treated mice were harvested at day 21 post-tumor implantation and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 µm. Antihuman survivin mAb (Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-PLK1 mAb (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) were used as primary antibodies for detection of survivin and PLK1 protein, respectively. Sections were also stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological examination of bladder tumor tissue.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Structure of DiLA2 molecule. The generic structure of a guanidinium-based DiLA2 molecule highlighting headgroup, spacer and linker regions is depicted. The lead guanidinium DiLA2 compound consists of a spacer region with n = 2 and C16 and C18:1 chains attached to the α-carboxyl and α-amino groups, respectively. Figure S2. Biodistribution of survivin UsiRNA in mouse bladder. Dual probe hybridization assay using biotin and fluorescein probes against antisense strand of survivin UsiRNA. Bladder tissues treated with 0.5 mg/kg of survivin UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes were collected at various time points ranging from 15 minutes to 24 h post dose. N=5 per time-point, Mean ± SE. Figure S3. RNAi effect with survivin UsiRNA alone or DiLA2-formulated survivin UsiRNA in bladder tumors. Bladders from tumor-bearing mice treated with survivin UsiRNA alone or DiLA2 encapsulated survivin UsiRNA at 1.0 mg/kg at days 2, 4, 5 and 9 were analyzed for reduction in survivin mRNA expression using qRT-PCR. Survivin mRNA levels were normalized to housekeeping genes HPRT1 and TBP expressed relative to buffer treated control using a relative quantification method. Values are represented as group mean ± SE, n=5 per time-point. Asterisk represents P <0.05 suggesting statistical significance of DiLA2 liposome/UsiRNA-treated group as compared to buffer control. Figure S4. Sequencing of survivin and PLK1 RISC cleavage products from UsiRNA-treated bladder tumors. Representative chromatogram images of the 5' RACE-PCR amplified cleaved product from bladder tumors treated with survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes. The PCR products obtained from the 5' RACE-PCR assay were sequenced by automated sequencer. (a) Sequencing of survivin positive clones identified a cleavage site at nucleotide position 8/9 from the 5' end of the guide strand. (b) Sequencing of PLK1 positive clones identified the predicted cleavage site at nucleotide position 10 and 11 (Position 910/911) from the 5' end of the guide strand. Figure S5. HPLC-UV/MS chromatogram. (a) C18:1-norArg-C16 was identified as total ion count (TIC) peak at 14.27 min retention time. (b) Scan under HPLC-MS peat at 14.27 min from Figure S5. C18:1-norArg-C16 was identified as molecular ion at 649 m/z for [M+H]+. Figure S6. HPLC-ELS chromatogram. Purity of C18:1-norArg-C16 (LP5797-9632) was 99.47% by total area.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Marina Biotech Inc. All authors except A.S. and Y.M. are employed by Marina Biotech Inc. In-life conducted at UBC, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and in vitro analysis performed at Marina Biotech, Inc., Bothell, WA.

Supplementary Material

Structure of DiLA2 molecule. The generic structure of a guanidinium-based DiLA2 molecule highlighting headgroup, spacer and linker regions is depicted. The lead guanidinium DiLA2 compound consists of a spacer region with n = 2 and C16 and C18:1 chains attached to the α-carboxyl and α-amino groups, respectively.

Biodistribution of survivin UsiRNA in mouse bladder. Dual probe hybridization assay using biotin and fluorescein probes against antisense strand of survivin UsiRNA. Bladder tissues treated with 0.5 mg/kg of survivin UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes were collected at various time points ranging from 15 minutes to 24 h post dose. N=5 per time-point, Mean ± SE.

RNAi effect with survivin UsiRNA alone or DiLA2-formulated survivin UsiRNA in bladder tumors. Bladders from tumor-bearing mice treated with survivin UsiRNA alone or DiLA2 encapsulated survivin UsiRNA at 1.0 mg/kg at days 2, 4, 5 and 9 were analyzed for reduction in survivin mRNA expression using qRT-PCR. Survivin mRNA levels were normalized to housekeeping genes HPRT1 and TBP expressed relative to buffer treated control using a relative quantification method. Values are represented as group mean ± SE, n=5 per time-point. Asterisk represents P <0.05 suggesting statistical significance of DiLA2 liposome/UsiRNA-treated group as compared to buffer control.

Sequencing of survivin and PLK1 RISC cleavage products from UsiRNA-treated bladder tumors. Representative chromatogram images of the 5' RACE-PCR amplified cleaved product from bladder tumors treated with survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes. The PCR products obtained from the 5' RACE-PCR assay were sequenced by automated sequencer. (a) Sequencing of survivin positive clones identified a cleavage site at nucleotide position 8/9 from the 5' end of the guide strand. (b) Sequencing of PLK1 positive clones identified the predicted cleavage site at nucleotide position 10 and 11 (Position 910/911) from the 5' end of the guide strand.

HPLC-UV/MS chromatogram. (a) C18:1-norArg-C16 was identified as total ion count (TIC) peak at 14.27 min retention time. (b) Scan under HPLC-MS peat at 14.27 min from Figure S5. C18:1-norArg-C16 was identified as molecular ion at 649 m/z for [M+H]+.

HPLC-ELS chromatogram. Purity of C18:1-norArg-C16 (LP5797-9632) was 99.47% by total area.

REFERENCES

- Barocas DA., and, Clark PE. Bladder cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:307–314. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f8b03e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaldone MC, Casella DP, Welchons DR., and, Gingrich JR. Investigational therapies for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:371–383. doi: 10.1517/13543780903563372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausladen DA, Wheeler MA, Altieri DC, Colberg JW., and, Weiss RM. Effect of intravesical treatment of transitional cell carcinoma with bacillus Calmette-Guerin and mitomycin C on urinary survivin levels and outcome. J Urol. 2003;170:230–234. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000063685.29339.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Shen T, Wientjes MG, O'Donnell MA., and, Au JL. Intravesical treatments of bladder cancer: review. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1500–1510. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9566-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wu W, Tahir SK, Kroeger PE, Rosenberg SH, Cowsert LM.et al. (2000Down-regulation of survivin by antisense oligonucleotides increases apoptosis, inhibits cytokinesis and anchorage-independent growth Neoplasia 2235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiong E., and, Esuvaranathan K. New therapies for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol. 2010;28:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0474-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan BJ, Gray S, Johnston SR, Williamson K, Miyaki H., and, Gleave M. The role of antisense oligonucleotides in the treatment of bladder cancer. Urol Res. 2002;30:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s00240-002-0248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuessel S, Kueppers B, Ning S, Kotzsch M, Kraemer K, Schmidt U.et al. (2004Systematic in vitro evaluation of survivin directed antisense oligodeoxynucleotides in bladder cancer cells J Urol 1716 Pt 12471–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada M, So A, Muramaki M, Rocchi P, Beraldi E., and, Gleave M. Hsp27 knockdown using nucleotide-based therapies inhibit tumor growth and enhance chemotherapy in human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:299–308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze D, Wuttig D, Kausch I, Blietz C, Blumhoff L, Burmeister Y.et al. (2008Antisense-mediated inhibition of survivin, hTERT and VEGF in bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo Int J Oncol 321049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake H, Hara I, Fujisaw M., and, Gleave ME. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide therapy for bladder cancer: recent advances and future prospects. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:1001–1009. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Mahendran R., and, Esuvaranathan K. Nonviral cytokine gene therapy on an orthotopic bladder cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4522–4528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Hadaschik BA, Fazli L, Andersen RJ, Gleave ME., and, So AI. Intravesical combination treatment with antisense oligonucleotides targeting heat shock protein-27 and HTI-286 as a novel strategy for high-grade bladder cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2402–2411. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogawa M, Yuasa T, Kimura S, Tanaka M, Kuroda J, Sato K.et al. (2005Intravesical administration of small interfering RNA targeting PLK-1 successfully prevents the growth of bladder cancer J Clin Invest 115978–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So A, Rocchi P., and, Gleave M. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy in the management of bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15:320–327. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000175572.46986.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Z, Mahendran R, Wu Q, Yong T., and, Esuvaranathan K. Non-viral tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene transfer decreases the incidence of orthotopic bladder tumors. Int J Mol Med. 2004;14:713–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuessel S, Meye A, Kraemer K, Kunze D, Hakenberg OW., and, Wirth MP. Synthetic nucleic acids as potential therapeutic tools for treatment of bladder carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2007;51:315–326; discussion 326. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri DC. Survivin in apoptosis control and cell cycle regulation in cancer. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennati M, Folini M., and, Zaffaroni N. Targeting survivin in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:463–476. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffaroni N, Pennati M., and, Folini M. Validation of telomerase and survivin as anticancer therapeutic targets using ribozymes and small-interfering RNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;361:239–263. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-208-4:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuessel S, Herrmann J, Ning S, Kotzsch M, Kraemer K, Schmidt U.et al. (2006Chemosensitization of bladder cancer cells by survivin-directed antisense oligodeoxynucleotides and siRNA Cancer Lett 232243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou JQ, He J, Wang XL, Wen DG., and, Chen ZX. Effect of small interfering RNA targeting survivin gene on biological behaviour of bladder cancer. Chin Med J. 2006;119:1734–1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning S, Fuessel S, Kotzsch M, Kraemer K, Kappler M, Schmidt U.et al. (2004siRNA-mediated down-regulation of survivin inhibits bladder cancer cell growth Int J Oncol 251065–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FA, Silljé HH., and, Nigg EA. Polo-like kinases and the orchestration of cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink J, Sanders K, Rippl A, Finkernagel S, Beckers TL., and, Schmidt M. Cell type– dependent effects of Polo-like kinase 1 inhibition compared with targeted polo box interference in cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6 12 Pt 1:3189–3197. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BT., and, Strebhardt K. Polo-like kinase 1: target and regulator of transcriptional control. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2881–2885. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.24.3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenski DM, Cooper AJ, Li JJ, Willingham AT, Haringsma HJ, Young TA.et al. (2010Analysis of acyclic nucleoside modifications in siRNAs finds sensitivity at position 1 that is restored by 5'-terminal phosphorylation both in vitro and in vivo Nucleic Acids Res 38660–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen MB, Pakula MM, Gao S, Fluiter K, Mook OR, Baas F.et al. (2010Utilization of unlocked nucleic acid (UNA) to enhance siRNA performance in vitro and in vivo Mol Biosyst 6862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaish N, Chen F, Seth S, Fosnaugh K, Liu Y, Adami R.et al. (2010Improved specificity of gene silencing by siRNAs containing unlocked nucleobase analogs Nucleic Acids Resepub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salz W, Eisenberg D, Plescia J, Garlick DS, Weiss RM, Wu XR.et al. (2005A survivin gene signature predicts aggressive tumor behavior Cancer Res 653531–3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp JD, Hausladen DA, Maher MG, Wheeler MA, Altieri DC., and, Weiss RM. Bladder cancer detection with urinary survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:e36–e41. doi: 10.2741/sharp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Wheeler MA, Plescia J, Colberg JW, Weiss RM., and, Altieri DC. Urine detection of survivin and diagnosis of bladder cancer. JAMA. 2001;285:324–328. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swana HS, Grossman D, Anthony JN, Weiss RM., and, Altieri DC. Tumor content of the antiapoptosis molecule survivin and recurrence of bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:452–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang JY., and, Huang ZR. Intravesical drug delivery into the bladder to treat cancers. Curr Drug Deliv. 2009;6:227–237. doi: 10.2174/156720109788680868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Barchet W, Schlee M., and, Hartmann G. RNA recognition via TLR7 and TLR8. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008. pp. 71–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hornung V, Guenthner-Biller M, Bourquin C, Ablasser A, Schlee M, Uematsu S.et al. (2005Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-alpha by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7 Nat Med 11263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge AD, Sood V, Shaw JR, Fang D, McClintock K., and, MacLachlan I. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nbt1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, Chandrasekaran V, Nozaki M, Baffi JZ.et al. (2008Sequence- and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3 Nature 452591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeck H, Besch R, Maihoefer C, Renn M, Tormo D, Morskaya SS.et al. (20085'-Triphosphate-siRNA: turning gene silencing and Rig-I activation against melanoma Nat Med 141256–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TB, Langkjaer N., and, Wengel J. Unlocked nucleic acid (UNA) and UNA derivatives: thermal denaturation studies. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2008. pp. 133–134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nielsen P, Dreiøe LH., and, Wengel J. Synthesis and evaluation of oligodeoxynucleotides containing acyclic nucleosides: introduction of three novel analogues and a summary. Bioorg Med Chem. 1995;3:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(94)00143-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaschik BA, Black PC, Sea JC, Metwalli AR, Fazli L, Dinney CP.et al. (2007A validated mouse model for orthotopic bladder cancer using transurethral tumour inoculation and bioluminescence imaging BJU Int 1001377–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Smallwood A, Chambers AE., and, Nicolaides K. Quantitative recovery of immunoreactive proteins from clinical samples following RNA and DNA isolation. BioTechniques. 2003;35:450–2, 454, 456. doi: 10.2144/03353bm02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Structure of DiLA2 molecule. The generic structure of a guanidinium-based DiLA2 molecule highlighting headgroup, spacer and linker regions is depicted. The lead guanidinium DiLA2 compound consists of a spacer region with n = 2 and C16 and C18:1 chains attached to the α-carboxyl and α-amino groups, respectively.

Biodistribution of survivin UsiRNA in mouse bladder. Dual probe hybridization assay using biotin and fluorescein probes against antisense strand of survivin UsiRNA. Bladder tissues treated with 0.5 mg/kg of survivin UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes were collected at various time points ranging from 15 minutes to 24 h post dose. N=5 per time-point, Mean ± SE.

RNAi effect with survivin UsiRNA alone or DiLA2-formulated survivin UsiRNA in bladder tumors. Bladders from tumor-bearing mice treated with survivin UsiRNA alone or DiLA2 encapsulated survivin UsiRNA at 1.0 mg/kg at days 2, 4, 5 and 9 were analyzed for reduction in survivin mRNA expression using qRT-PCR. Survivin mRNA levels were normalized to housekeeping genes HPRT1 and TBP expressed relative to buffer treated control using a relative quantification method. Values are represented as group mean ± SE, n=5 per time-point. Asterisk represents P <0.05 suggesting statistical significance of DiLA2 liposome/UsiRNA-treated group as compared to buffer control.

Sequencing of survivin and PLK1 RISC cleavage products from UsiRNA-treated bladder tumors. Representative chromatogram images of the 5' RACE-PCR amplified cleaved product from bladder tumors treated with survivin or PLK1 UsiRNA in DiLA2 liposomes. The PCR products obtained from the 5' RACE-PCR assay were sequenced by automated sequencer. (a) Sequencing of survivin positive clones identified a cleavage site at nucleotide position 8/9 from the 5' end of the guide strand. (b) Sequencing of PLK1 positive clones identified the predicted cleavage site at nucleotide position 10 and 11 (Position 910/911) from the 5' end of the guide strand.

HPLC-UV/MS chromatogram. (a) C18:1-norArg-C16 was identified as total ion count (TIC) peak at 14.27 min retention time. (b) Scan under HPLC-MS peat at 14.27 min from Figure S5. C18:1-norArg-C16 was identified as molecular ion at 649 m/z for [M+H]+.

HPLC-ELS chromatogram. Purity of C18:1-norArg-C16 (LP5797-9632) was 99.47% by total area.