Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that age-related endothelial dysfunction in rat soleus muscle feed arteries (SFA) is mediated in part by NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS). SFA from young (4 mo) and old (24 mo) Fischer 344 rats were isolated and cannulated for examination of vasodilator responses to flow and acetylcholine (ACh) in the absence or presence of a superoxide anion (O2−) scavenger (Tempol; 100 μM) or an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor (apocynin; 100 μM). In the absence of inhibitors, flow- and ACh-induced dilations were attenuated in SFA from old rats compared with young rats. Tempol and apocynin improved flow- and ACh-induced dilation in SFA from old rats. In SFA from young rats, Tempol and apocynin had no effect on flow-induced dilation, and apocynin attenuated ACh-induced dilation. To determine the role of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), dilator responses were assessed in the absence and presence of catalase (100 U/ml) or PEG-catalase (200 U/ml). Neither H2O2 scavenger altered flow-induced dilation, whereas both H2O2 scavengers blunted ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats. In old SFA, catalase improved flow-induced dilation whereas PEG-catalase improved ACh-induced dilation. Compared with young SFA, in response to exogenous H2O2 and NADPH, old rats exhibited blunted dilation and constriction, respectively. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the NAD(P)H oxidase subunit gp91phox protein content was greater in old SFA compared with young. These results suggest that NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species contribute to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in old SFA.

Keywords: superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, superoxide dismutase, catalase, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

aging is associated with a decline in maximal exercise capacity (13, 18, 26, 33), which is due in part to impaired exercise hyperemia (3, 12, 19, 24, 32, 34, 35). Emerging evidence in humans and animals suggests that with age, endothelial dysfunction limits vasodilation in the skeletal muscle vascular beds, particularly in oxidative muscle (24, 31, 44, 55). The feed artery is of particular importance as it is a primary control point for regulating total blood flow to the soleus muscle at rest and during exercise (53). Because of the rat soleus muscle feed artery (SFA)'s importance in regulating muscle blood flow at rest and exercise, our laboratory has focused on determining the mechanisms that influence endothelial function in this vessel with age. We have previously demonstrated impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in the SFA, which is primarily due to attenuated nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (50, 54–57).

Increased NO degradation by superoxide anion (O2−) has been implicated as a major mechanism for age-related endothelial dysfunction (7, 10, 41–43, 50, 52). A number of potential sources of O2− exist in the aged vasculature, including NAD(P)H oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and mitochondrial sources (7, 20, 51). In addition, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), in the absence of its cofactor tetrahyrobiopterin (BH4), can produce O2− (4, 8, 16, 40). We have recently reported that scavenging O2− with exogenous superoxide dismutase (SOD) improves NO-mediated, endothelium-dependent dilation in senescent rat SFA (50). Similarly, exogenous antioxidants improve vasodilation (15) and exercise hyperemia (24) in the aged human forearm vasculature. Interestingly, Sindler et al. (40) recently reported that inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production or scavenging of O2− attenuated flow-induced dilation in soleus first-order (1A) arterioles from both young and old rats. In addition, these investigators reported that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) plays a role in flow-induced dilation in soleus 1A (40). Vascular H2O2 can be generated by SOD scavenging of O2−, spontaneous dismutation of O2−, and by direct production from NAD(P)H oxidase (9, 29, 59). H2O2 has been implicated in some studies as a vasodilator in the aged vasculature (23, 40) whereas other studies suggest that H2O2 contributes to age-related endothelial dysfunction (47, 48, 51).

Due to the apparent contrast between our data and that of Sindler et al. (40), the ambiguous role of H2O2 in endothelial function with age and the differing location and roles of the SFA (outside the muscle, regulation of total muscle blood flow) and the 1A arteriole (inside the muscle, regulation of blood flow within the muscle), we sought to determine whether ROS play a role in age-related endothelial dysfunction in rat SFA. We hypothesized that age-related endothelial dysfunction in rat SFA is mediated, in part, by NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS.

METHODS

Animals

The methods used in this study were approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Fischer 344 rats [4 mo (n = 47) and 24 mo of age (n = 44)] were acquired from the National Institute of Aging (NIA) and housed at the College of Veterinary Medicine's Comparative Medicine Program Facility. Rats were housed under a 12:12-h light-dark cycle, and food and water were provided ad libitum. The rats were examined daily by Comparative Medicine Program veterinarians. Fischer 344 rats were chosen, in part, because of the absence of atherosclerosis or hypertension with age (26); thus we could examine the effect of aging in the absence of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Isolation of Feed Arteries

The protocol for SFA isolation has been described previously in detail (54–57). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with an injection of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg body wt ip). The soleus/gastrocnemius muscle complex was dissected from both hindlimbs and was placed in a MOPS-buffered physiological saline solution (PSS), containing (in mM) 145.0 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.17 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 5.0 glucose, 2.0 pyruvate, 0.02 EDTA, and 25.0 MOPS (pH 7.4). SFA were dissected free and transferred to a Lucite chamber containing MOPS-PSS (2 ml) for cannulation. SFA not used for isolated artery studies were dissected, transferred to a microcentifuge tube, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C for subsequent biochemical analyses.

Determination of Vasodilator Responses

Preparation of arteries.

SFA were cannulated with two resistance-matched glass micropipettes and secured with a single strand of surgical thread. The micropipettes were attached to separate reservoirs filled with MOPS-PSS supplemented with albumin (1 g/100 ml). The height of each reservoir was adjusted to set intraluminal pressure in each feed artery to 60 cmH2O (1 mmHg = 1.36 cm H2O) for 20 min. SFA were checked for leaks by verification that intraluminal diameter was maintained after closing the pressure reservoirs. After 20 min, intraluminal pressure was raised to 90 cmH2O and the SFA were allowed to equilibrate for an additional 40 min at 37°C. At the end of the equilibration period, arteries that did not develop at least 25% spontaneous tone were discarded. All experimental protocols were conducted at an intraluminal pressure of 90 cmH2O to approximate in vivo SFA pressure (53).

Assessment of vasodilation.

Endothelium-dependent, flow-induced dilation was assessed by establishing intraluminal flow in the SFA by raising and lowering the heights of the pressure reservoirs in equal but opposite directions while maintaining constant pressure at the midpoint of the artery (25). Vasodilator responses to flow were assessed at pressure gradients of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40 cmH2O, corresponding to flow rates of 0–62 μl/min. Each flow rate was maintained for 5 min to allow SFA to reach a steady diameter. Endothelium-dependent, acetylcholine (ACh)-induced dilation was assessed in SFA by adding cumulative, increasing, whole log doses of ACh over the range of 10−9–10−4 M. Endothelium-independent dilation was assessed in SFA by addition of cumulative, increasing, whole log doses of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) over the range of 10−9–10−4 M.

Effects of ROS on Endothelium-Dependent Dilation

To determine the role and source of vascular ROS, endothelium-dependent vasodilator responses were assessed in the absence and presence of Tempol (100 μM, a cell-permeable SOD mimetic) and apocynin (100 μM), an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor (22, 28, 38, 45). Tempol or apocynin was added to the vessel bath 30 min before assessing the dilator responses.

To determine the role of H2O2 in endothelium-dependent dilations, vasodilator responses were assessed in the absence and presence of catalase (100 U/ml, a non-cell-permeable H2O2 scavenger) and PEG-catalase (200 U/ml, a cell-permeable H2O2 scavenger). Catalase or PEG-catalase was added to the vessel bath for 30 min before assessing the dilator responses.

Assessment of Vascular Responses to Exogenous and Endogenous ROS

To determine the role of exogenous H2O2 in vascular reactivity of young and old SFA, H2O2 was added to the vessel bath in cumulative, increasing, whole log doses over the range of 10−7–10−2 M.

To determine the role of endogenous ROS in vascular reactivity of young and old SFA, NADPH [substrate for NAD(P)H oxidase] was added to the vessel bath in cumulative, increasing, whole log doses over the range of 10−7–10−4 M, concentrations previously shown to elicit relaxation in rat arteries (29).

Immunoblotting

Relative protein content of NAD(P)H oxidase subunits, SOD isoforms, and catalase were assessed in single SFA using immunoblotting techniques described previously in detail (21). The following NAD(P)H subunit protein contents were assessed using monoclonal antibodies: gp91phox (1:1,000, BD Biosciences, catalog no. G95320), p47phox (1:1,000, BD Biosciences, catalog no. P33720), p67phox (1:250, BD Biosciences, catalog no. 610912), and Nox-1 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-25545). The following SOD isoform protein contents were assessed using polyclonal antibodies: Cu/Zn SOD (1:3,333, Assay Designs, catalog no. SOD-100), mitochondrial SOD (mnSOD) (1:6,000, Assay Designs, catalog no. SOD-110), and extracellular SOD (ecSOD) (1:1,000, Assay Designs, catalog no. SOD-105). Catalase protein contents were assessed using a monoclonal antibody (1:1,000, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. C-0979). In addition, relative SFA nitrotyrosine content was assessed using a polyclonal antibody (1:1,000, Millipore, catalog no. AB5411). Immunoblots were evaluated by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham) and densitometry by using a LAS-4000 Luminescent Image Analyzer and Multi-Gauge Image Analysis Software (FUJIFILM Medical Systems). Protein data were expressed relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) to control for small differences in protein loading. GAPDH protein content was assessed with a monoclonal antibody (1:10,000, Millipore, catalog no. AB374). Because the nitrotyrosine antibody binds with nitrosyolated tyrosine residues across the range of molecular weights, the optical density of each whole lane (representing 1 whole SFA) was quantified and expressed as a ratio of GAPDH density.

SOD Activity Assay

Single SFA were solubilized in 20 μl of 20 mM HEPES buffer using repeated freeze-thaw cycles. SFA SOD activity was assessed using a commercially available SOD activity assay kit (Cayman Chemical) as previously described (14) and assessed colorimetrically. The remainder of the sample was used to determine total protein content using a commercially available kit (Micro BCA, Pierce).

Drugs

All drugs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and with the exception of apocynin were dissolved in PSS. Apocynin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) such that the concentration of DMSO in the vessel bath did not exceed 0.1%. Pilot studies revealed that this concentration did not alter endothelium-dependent or -independent dilations.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. Between-group differences in body mass, maximal diameters, %spontaneous tone, relative protein content, and SOD activity were assessed by using Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA where appropriate. Vasodilator response data were assessed as percent possible dilation calculated as [(Ddose − DB)/(DP − DB)] × 100, where Ddose is the measured diameter for a give dose/flow rate, DB is the baseline diameter before the dose-response curve, and DP is maximal passive diameter. Maximal passive diameter was assessed by incubating the SFA in Ca2+-free PSS for 30 min. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with repeated measures on one factor (dose/flow rate) was used to determine differences in dilator responses. Statistical significance was set a P ≤ 0.05 probability level.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Rats and SFA

Body weight and maximal vessel diameter were significantly greater in old rats compared with young (Table 1). Spontaneous myogenic tone was not altered with either age or pharmacological treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Animal and vessel characteristics

| Young | Old | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 376 ± 6 | 411 ± 7* |

| Vessel characteristics | ||

| Maximal diameter, μm | 160 ± 4 | 176 ± 5* |

| Spontaneous tone, % | ||

| Pre-flow | ||

| Control | 41 ± 3 | 40 ± 2 |

| Tempol | 46 ± 4 | 37 ± 3 |

| Apocynin | 46 ± 5 | 49 ± 7 |

| Catalase | 45 ± 4 | 34 ± 2 |

| PEG-catalase | 40 ± 3 | 38 ± 4 |

| Pre-acetylcholine | ||

| Control | 38 ± 2 | 40 ± 3 |

| Tempol | 37 ± 3 | 37 ± 3 |

| Apocynin | 41 ± 4 | 49 ± 8 |

| Catalase | 38 ± 3 | 37 ± 2 |

| PEG-catalase | 35 ± 2 | 33 ± 2 |

| Pre-H2O2 | 42 ± 4 | 40 ± 4 |

| Pre-NADPH | 37 ± 5 | 36 ± 4 |

Values are means ± SE.

Significantly different from young, P ≤ 0.05.

Vasodilator Responses

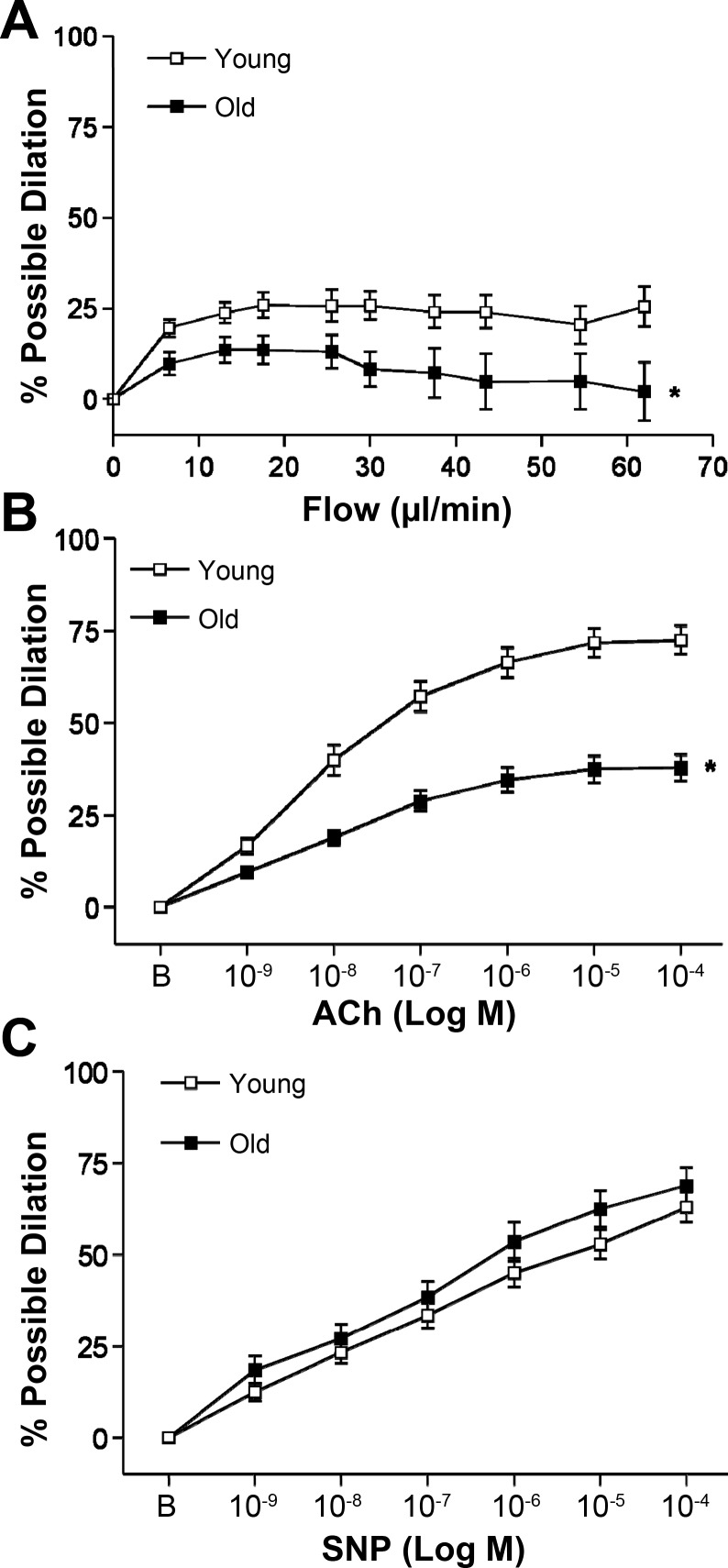

Both flow- and ACh-induced dilations were attenuated with age (Fig. 1, A and B). SNP-induced (endothelium-independent) dilation was not altered with age (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Flow-induced (A), ACh-induced (B), and sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-induced (C) dilation in soleus muscle feed arteries (SFA). B is baseline diameter before the first dose of ACh or SNP. Values are means ± SE; n sizes: young flow (n = 34), old flow (n = 36), young ACh (n = 37), old ACh (n = 34), young SNP (n = 22), old SNP (n = 22). *Dose-response curve significantly different from young, P ≤ 0.05.

Role of O2− in Endothelium-Dependent Dilation

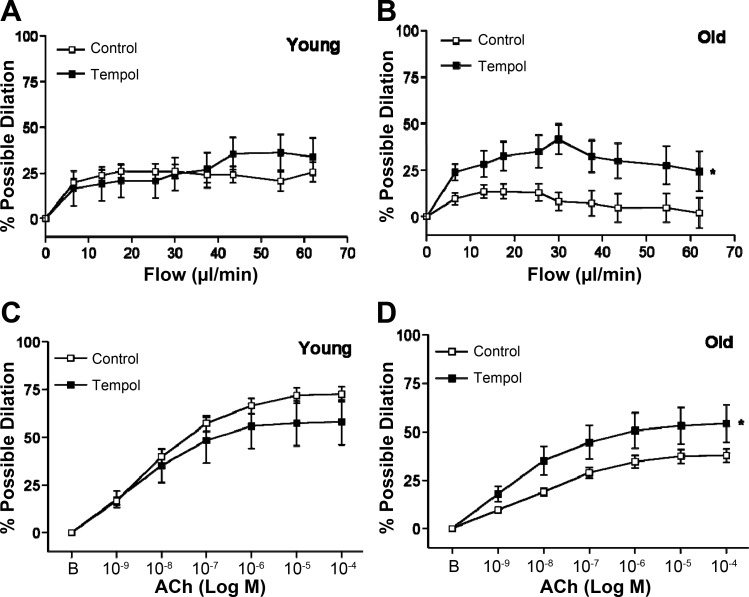

In SFA from young rats, scavenging of O2− with Tempol did not alter flow-induced dilation (Fig. 2A). In SFA from old rats, Tempol significantly improved flow-induced dilation (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the presence of Tempol did not alter ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats and improved dilation in SFA from old rats (Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 2.

Flow-induced (A and B) dilation in SFA in the absence or presence of superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic Tempol (100 μM); n sizes: young control (n = 24), young + Tempol (n = 10), old control (n = 29), old + Tempol (n = 10). ACh-induced (C and D) dilation in SFA in the absence or presence of Tempol; n sizes: young control (n = 30), young + Tempol (n = 11), old control (n = 30), old + Tempol (n = 11). B is baseline diameter before the first dose of ACh. Values are means ± SE. *Dose-response curve significantly different from control, P ≤ 0.05.

Apocynin did not alter flow-induced dilation in SFA from young rats (Fig. 3A) whereas apocynin significantly improved flow-induced dilation in SFA from old rats (Fig. 3B). Apocynin attenuated ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats (Fig. 3C) and improved ACh-induced dilation in SFA from old rats (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Flow-induced (A and B) in SFA in the absence or presence of apocynin (100 μM); n sizes: young control (n = 24), young + apocynin (n = 11), old control (n = 29), old + apocynin (n = 8). ACh-induced (C and D) dilation in SFA in the absence or presence of apocynin; n sizes: young control (n = 28), young + apocynin (n = 11), old control (n = 29), old + apocynin (n = 8). B is baseline diameter before the first dose of ACh. Values are means ± SE. *Dose-response curve significantly different from control, P ≤ 0.05.

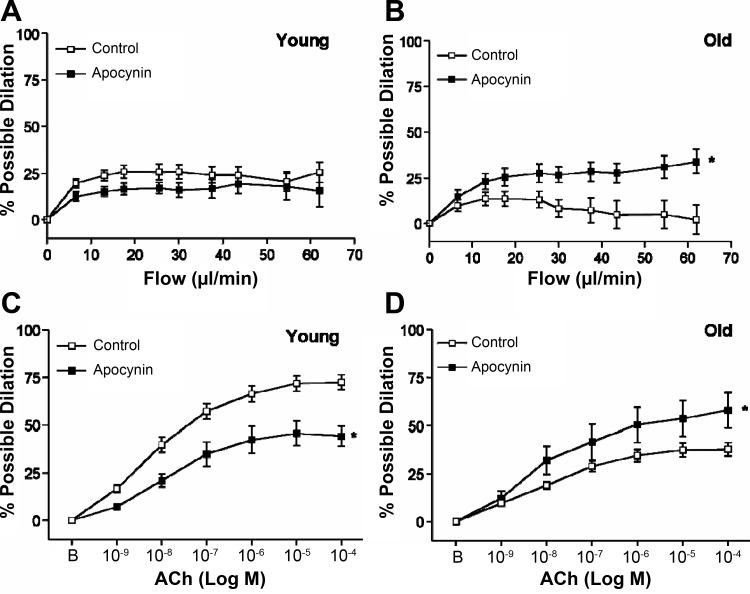

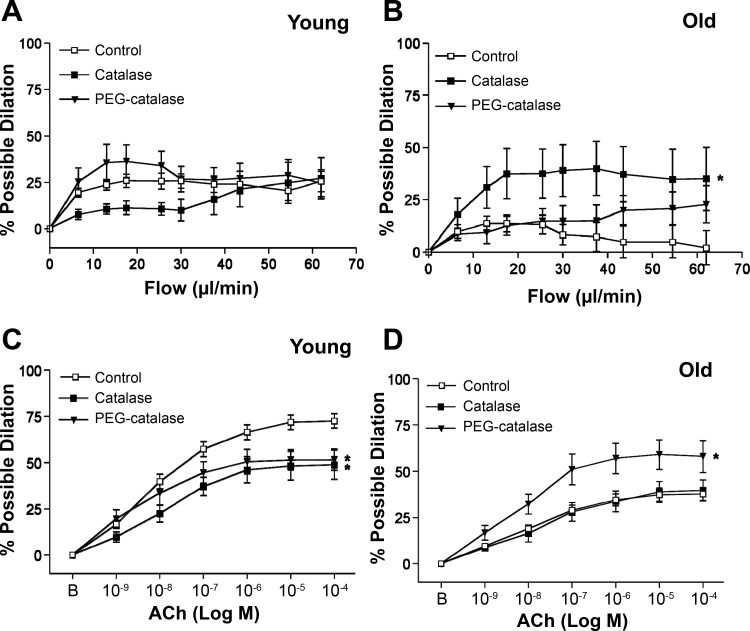

Role of H2O2 in Endothelium-Dependent Dilation

Neither catalase (extracellular H2O2 scavenging) nor PEG-catalase (intracellular H2O2 scavenging) significantly altered flow-induced dilation in SFA from young rats (Fig. 4A). There was a tendency (P = 0.07) for a group-by-flow rate interaction, but this was not statistically significant. In contrast, both catalase and PEG-catalase blunted ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats (Fig. 4C). In SFA from old rats, catalase significantly improved flow-induced dilation (Fig. 4B), and PEG-catalase significantly improved ACh-induced dilation (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Flow-induced (A and B) dilation in SFA in the absence or presence of catalase (an extracellular H2O2 scavenger, 100 U/ml) or PEG-catalase (an intracellular H2O2 scavenger, 200 U/ml); n sizes: young control (n = 24), young + catalase (n = 8), young + PEG-catalase (n = 8), old control (n = 29), old + catalase (n = 7), old + PEG-catalase (n = 8). ACh-induced (C and D) dilation in SFA in the absence or presence of catalase or PEG-catalase; n sizes: young control (n = 28), young + catalase (n = 8), young + PEG-catalase (n = 9), old control (n = 29), old + catalase (n = 8), old + PEG-catalase (n = 8). B is baseline diameter before the first dose of ACh. Values are means ± SE. *Dose-response curve significantly different from control, P ≤ 0.05.

Vascular Responses to Exogenous and Endogenous ROS

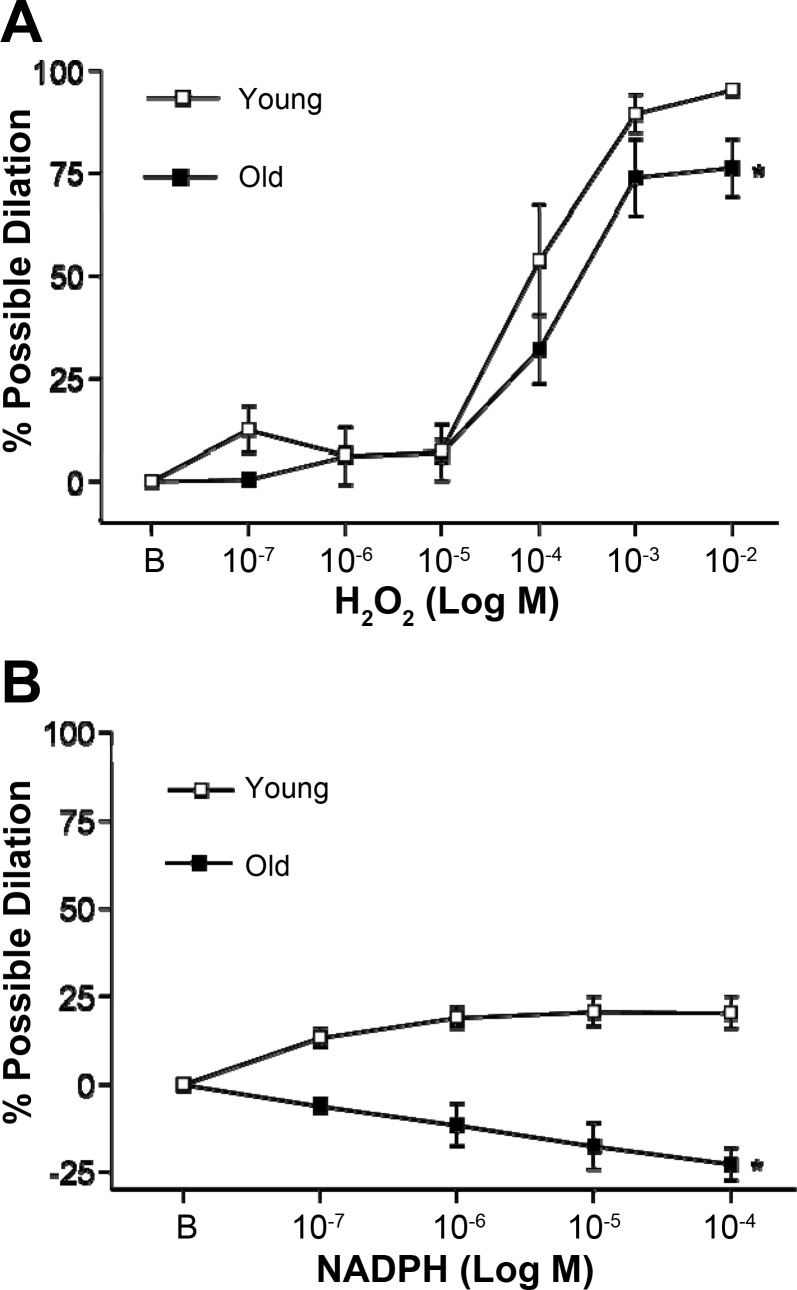

Increasing concentrations of H2O2 (exogenous ROS) resulted in significant vasodilation in SFA from both young and old animals; however, this dilator response was blunted with age (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

H2O2- (A) and NADPH- (B) induced vascular responses in SFA. A: n = 7 (young) and n = 8 (old). B: n = 6 (young) and n = 7 (old). B is baseline diameter before the first dose of H2O2 or NADPH. Values are means ± SE. *Curve significantly different from young, P ≤ 0.05.

In response to NADPH, SFA from young animals exhibited modest dilation. In contrast, vessels from old animals exhibited vasoconstriction (Fig. 5B).

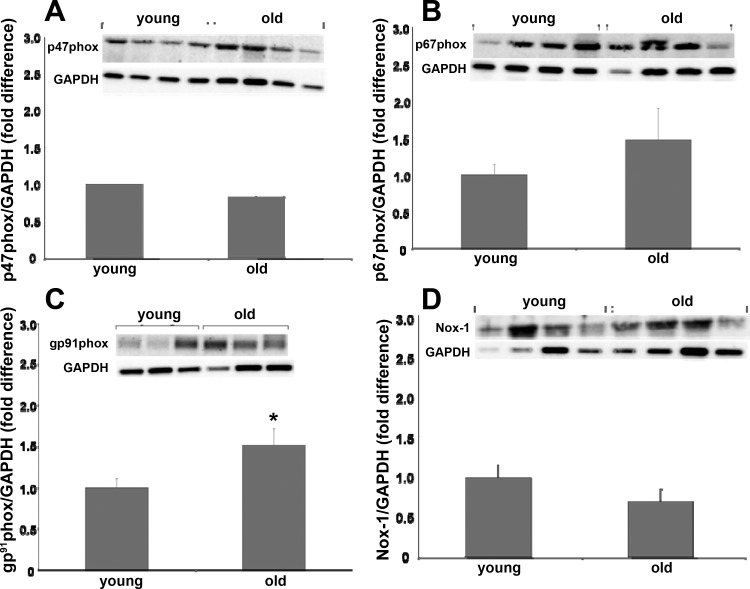

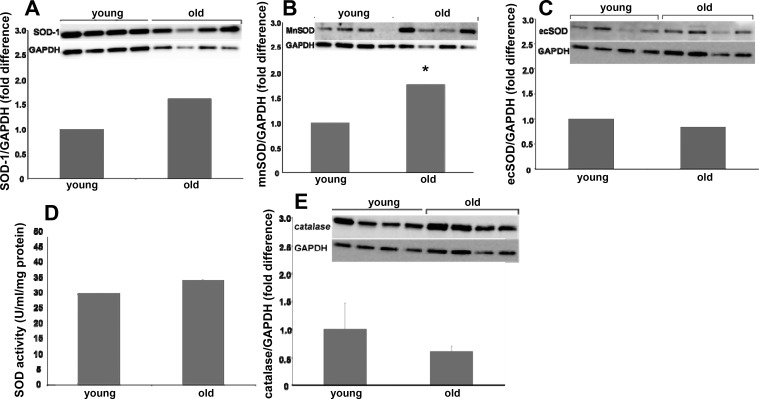

Immunoblotting

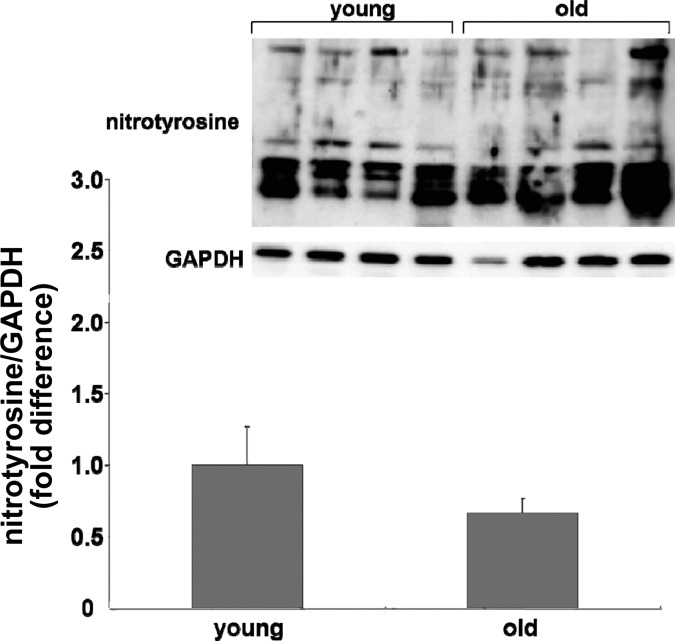

Immunoblot analysis for NAD(P)H oxidase subunits revealed that age resulted in increased gp91phox protein content (Fig. 6C) whereas age did not alter p47phox, p67phox, or Nox-1 protein content (Fig. 6, A, B, and D). Immunoblots for SOD isoform protein content revealed that SOD-1 and ecSOD protein contents from SFA from young and old rats were similar (Fig. 7, A and C). mnSOD protein content was greater in SFA from old rats compared with young (Fig. 7B). SOD enzyme activity was not altered with age (Fig. 7D). Catalase protein content was not altered with age (Fig. 7E). Nitrotyrosine expression was not statistically different (P = 0.1) with age (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of NAD(P)H oxidase subunit protein contents p47phox (A), p67phox (B), gp91phox (C), and Nox-1 (D) in SFA from young and old rats. Insets: representative blots for the target protein (top image) and the same blot reprobed for GAPDH (bottom image). Values are means ± SE; n = 8–16 rats/group. *Significantly different from young, P ≤ 0.05.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of Cu-Zn-dependent superoxide dismutase (SOD-1) protein content (A), mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (mnSOD) protein content (B), extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) protein content (C), total superoxide dismutase activity (D), and catalase protein content (E) in SFA from young and old rats. Insets: representative blots for the target protein (top image) and the same blot reprobed for GAPDH (bottom image). Values are means ± SE; n = 8–16 rats/group. *Significantly different from young, P ≤ 0.05.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of nitrotyrosine expression in SFA from young and old rats. Inset: representative blots for nitrotyrosine (top image) and the same blot reprobed for (bottom image). Values are means ± SE; n = 12 (young) and n = 15 (old).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that age-related endothelial dysfunction in rat SFA is mediated in part by NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS. The major new findings of this study are as follows: 1) O2− scavenging, NAD(P)H oxidase inhibition, and H2O2 scavenging improved endothelium-dependent dilation in SFA from old rats; 2) NAD(P)H oxidase inhibition and H2O2 scavenging attenuated ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats;. 3) both exogenous and endogenous ROS elicited dilation in SFA from young rats but these dilations were blunted (exogenous) or reversed (endogenous) in SFA from old rats; and 4) NAD(P)H oxidase subunit gp91phox protein content was greater in SFA from old compared with young rats. Collectively, these results suggest that NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS contribute to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in old SFA, whereas these ROS play a role in dilation in SFA from young rats.

Age is associated with impairment in endothelial function in conduit and resistance arteries in humans and animals including the SFA (2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 31, 46, 52, 54). SFA were used in this study because the SFA is a primary control point for regulating total muscle blood flow to the soleus muscle at rest and during exercise (53). In addition, exercise hyperemia to oxidative muscle (including the soleus) is attenuated with age (32). An impaired ability of the SFA to dilate during physical activity may contribute to attenuated exercise hyperemia and exercise capacity. In the present study, the findings that age attenuates both flow- and ACh-induced dilation are in accord with previous studies from our laboratory demonstrating endothelial dysfunction with age in the SFA (50, 54–57). Also in accord with our previous studies, endothelium-independent dilation was not altered with age (54–57), suggesting that the ability of the vascular smooth muscle to respond to NO is preserved.

The precise mechanisms that mediate dilation of the skeletal muscle vasculature during exercise are not fully understood; however, understanding the basic mechanisms that regulate endothelial function may provide insight into the more specific condition of exercise. Examining both flow- and ACh-dilation provides the advantage of examining a dilator pathway (flow) that is primarily NO- and prostacyclin dependent (55) and a pathway (ACh) that is dependent on NO, prostacyclin, and EDHF (50, 55). Lastly, examining diverse mechanisms of endothelium-dependent dilation provides insight as to whether a specific ligand/receptor-mediated dilation is impaired with age or if endothelial function on the whole is impaired.

We have previously shown that exogenous SOD improved ACh-induced dilation in a NO-dependent manner in senescent SFA (50). This led us to hypothesize that with age, vascular O2− limits endothelium-dependent dilation. We found that scavenging of O2− with the SOD mimetic Tempol or treatment with apocynin improved endothelium-dependent dilations in SFA from old rats. Apocynin has been shown to inhibit translocation of p47phox and p67phox [NAD(P)H oxidase regulatory subunits] to the cell membrane, resulting in decreased enzyme activity (22, 28, 45). It should be noted that apocynin has recently been shown to exhibit antioxidant effects in certain conditions rather than acting as a specific as an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor (17). Therefore a measure of caution should be used in interpreting results where apocynin is used.

Interestingly, Sindler et al. (40) found that in senescent soleus 1A arterioles both O2− scavenging with Tempol and apocynin treatment attenuated flow-induced dilation. This difference may be explained by the difference in anatomic location of the vessel as the SFA is external to the soleus whereas the 1A arteriole is internal. As contracting muscle releases ROS (36), the apparently ROS-mediated dilations of the 1A arterioles suggest that muscle-derived ROS may mediate dilation of these vessels during exercise and that the ability to dilate in response to ROS is preserved with age. In contrast, the feed artery is external to the muscle and may be exposed to different concentrations and/or respond differently to extravascular ROS.

Since H2O2 has been implicated as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) in some studies (23, 30, 40) but contributes to endothelial dysfunction in others (47, 48, 51), we also sought to determine the role of H2O2 in endothelial dysfunction. We utilized both extracellular (catalase) and intracellular (PEG-catalase) H2O2 scavengers and found that scavenging of H2O2 did not significantly alter flow-induced dilation, but blunted ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats. In SFA from old rats, catalase treatment improved flow-induced dilation, whereas PEG-catalase improved ACh-induced dilation. These results suggest that with age H2O2 impairs endothelium-dependent dilation in the rat SFA. These results are in contrast to those observed in soleus 1A arterioles (40) and underscore the important differences in mechanisms regulating vascular reactivity in feed arteries vs. arterioles despite their proximity. The finding that extracellular H2O2 scavenging improved flow-induced dilation and intracellular H2O2 scavenging improved ACh-dilation in SFA from aged rats indicates the location of H2O2 is important in the regulation of vascular function.

Previously we have shown that combined scavenging of O2− and H2O2 improved endothelial function in senescent SFA (50). In the present study scavenging of either O2− or H2O2 improved endothelial function in senescent SFA; these findings are intriguing as SOD, or an SOD mimetic, acts to increase H2O2 concentrations. Although, H2O2 can act as a vasodilator there are a number of mechanisms by which it may contribute to endothelial dysfunction. First, H2O2 promotes a proinflammatory state in aged rat conduit arteries, which may contribute to endothelial dysfunction (51). Second, Zhou et al. (60) have recently shown that increased H2O2 in senescent rat mesenteric arteries blunts flow-induced increases in NO-concentration, suggesting that chronic elevations of H2O2 alter endothelial function. Third, in response to exogenous H2O2 the endothelium produces both NO and cycloxygenase-derived prostaglandins (both dilators and constrictors) (1, 6, 39); thus it is conceivable that in the skeletal muscle vasculature aging results in a shift in this balance to favor production constrictors. Taken together these data suggest that O2− and H2O2 may act through different pathways to impair endothelial function with age and that scavenging one of these radicals may be adequate to result in some improvement in endothelial function.

The finding that scavenging of H2O2 and treatment with apocynin blunt dilation in SFA from young rats (Fig. 3) is intriguing as it suggests that ROS contribute to ACh-induced dilation in young vessels. Importantly, H2O2 has been implicated as an EDHF and also appears to play a role in eNOS phosphorylation and activation (30, 49). We have previously shown that a significant amount of ACh-induced dilation in rat SFA is EDHF dependent (50, 55), whereas flow-induced dilation is primarily NO and prostacyclin mediated (55). This difference may explain why H2O2 scavenging only blunted ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats. Apocynin also blunted ACh-induced dilation (Fig. 3C). NAD(P)H oxidase is a major source of vascular H2O2, both from dismutation of O2− and direct H2O2 production (9, 59). This may explain the inhibitory effect of apocynin on ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats. Importantly, recent investigations have shown that an oral antioxidant cocktail improves exercise-induced dilation of the brachial artery in old subjects, whereas in young subjects antioxidants blunt dilation (11, 37). This supports the concept that ROS contribute to dilation in young subjects but with age contribute to endothelial dysfunction.

To further investigate the role of ROS in SFA vascular reactivity we exposed SFA from young and old rats to increasing concentrations of exogenous H2O2. In response to H2O2 SFA from young and old rats exhibited dilation. However, this vasodilator response was blunted with age. This is in accord with observations in rat coronary arterioles (23). H2O2 has been shown to act as an EDHF, mediate phosphorylation of eNOS, and induce production of prostacyclin (1, 6, 30, 39, 49); however, H2O2 has also been shown to induce release of cyclooxygenase-derived constrictors in gracilis muscle arterioles (6). It is conceivable that with age, H2O2-induces greater release of prostanoid constrictors, explaining the blunted vasodilator response to H2O2. This supports the concept that H2O2 may influence endothelial function through different pathways than those of O2−.

In addition to assessing vascular responsiveness to H2O2 we sought to induce release of endogenous ROS by activating NAD(P)H oxidase. By increasing substrate availability for NAD(P)H oxidase, NADPH induces an H2O2-mediated relaxation of arteries from the cerebral and systemic circulation (29). In the present investigation, increasing concentrations of NADPH resulted in modest dilation in SFA from young animals, whereas NADPH resulted in constriction in SFA from old animals. Together with the observations that apocynin treatment and scavenging of H2O2 blunt dilation in young SFA but enhance dilation in old vessels, these results support the concept that NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS play a role in dilation in young SFA but with age mediate constriction. The observation that responses to both exogenous and endogenous ROS are altered with age suggests two potential ways by which ROS alter vascular function with age: 1) the vascular response to ROS may be altered, and/or 2) vascular concentrations of ROS may be altered. Elucidating precisely how ROS function in the healthy and aged skeletal muscle vasculature is an important topic for future study.

With age there appear to be multiple sources of vascular ROS. These sources include NAD(P)H oxidase, xanthine oxidase, mitochondrial sources, and eNOS (in the absence of it's cofactor BH4) (4, 7, 8, 16, 20, 40, 51). NAD(P)H oxidase is a membrane-bound enzyme complex with several subunits (38). The finding that NAD(P)H subunit gp91phox protein content is increased with age is of significance as gp91phox is homologous to the catalytic subunit Nox-2, which facilitates the transfer of electrons from NAD(P)H to molecular oxygen, yielding O2− (38). Nox-1, a different isoform of the catalytic subunit, was not altered with age. p47phox and p67phox bind to the catalytic subunit and facilitate electron flow through the catalytic subunit. In the present study, these protein contents were not altered with age. This is in contrast with findings in conduit vessels from aged humans and mice demonstrating increased p47phox and p67phox, respectively (10, 14). The age-related increase in protein content of the catalytic subunit gp91phox is in accord with the finding that apocynin improved endothelium-dependent dilation and that NADPH elicited vasoconstriction in old SFA, suggesting that NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS play a role in age-induced endothelial dysfunction in the SFA. In addition to NAD(P)H oxidase, it appears that eNOS is also a source of O2− in the skeletal muscle resistance vasculature. In soleus 1A a precursor of BH4 improved endothelial function, and inhibition of eNOS resulted in lower vascular O2− concentrations (8, 40). It is conceivable that in the aged skeletal muscle vasculature, these two mechanisms are linked in that O2− derived from NAD(P)H oxidase may oxidize BH4, limiting its availability and resulting in eNOS uncoupling and further O2− production.

In addition to hypothesizing that with age ROS production contributes to endothelial dysfunction, we hypothesized that decreased ROS scavenging would also contribute to the observed decline in endothelium-dependent dilation. Previously we have shown that exercise training improved endothelial function in senescent SFA and that this improvement was mediated by an increase in ecSOD protein content (50). In the present study we found that SOD-1, ecSOD, and catalase protein contents and SOD activity were not altered with age. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that the mnSOD protein content was greater in SFA from old rats compared with young. This finding may be reflective of a compensatory cellular response in attempt to combat greater O2− concentrations. In addition, it is interesting to note that the mitochondrial isoform of SOD (mnSOD) was enhanced with age, and mitochondrially derived ROS appear to play a role in vascular aging in rat conduit arteries (51).

Contrary to our hypothesis, nitrotyrosine expression was not significantly altered with age. Nitrotyrosine is an index of peroxynitrite, the product of NO and O2−. As scavenging of O2− improves endothelium-dependent dilation in senescent SFA it appears that excess O2− plays a role in endothelial dysfunction. It is possible that the concentrations of vascular O2− that induce endothelial dysfunction are lower than those that result in increases in nitrotyrosine. In addition, there are a number of potential mechanisms by which NO production may be reduced with age (27, 41–43, 58). It is conceivable that reduced NO production with age reduces the availability of NO for reaction with O2−.

In summary, we tested the hypothesis that age-related endothelial dysfunction in rat SFA is mediated, in part by NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS. The findings of the present study suggest that NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS attenuate endothelium-dependent dilation in senescent rat SFA. In contrast, it appears that NAD(P)H oxidase-derived H2O2 play a role in ACh-induced dilation in young rat SFA. These results suggest that ROS contribute to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in old SFA; however, ROS appear to play a role in ACh-induced dilation in SFA from young rats.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association, South Central Affiliate Grants 0765043Y and 4150031 (C. R. Woodman), National Institute on Aging Grant AG-00988 (C. R. Woodman), an American College of Sports Medicine Foundation Research Grant (D. W. Trott), and a Sydney and J. L. Huffines Institute of Sports Medicine and Human Performance Graduate Student Research Grant (D. W. Trott).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Ager A, Gordon JL. Differential effects of hydrogen peroxide on indexes of endothelial cell function. J Exp Med 159: 592–603, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barton M, Cosentino F, Brandes RP, Moreau P, Shaw S, Luscher TF. Anatomic heterogeneity of vascular aging: role of nitric oxide and endothelin. Hypertension 30: 817–824, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beere PA, Russell SD, Morey MC, Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB. Aerobic exercise training can reverse age-related peripheral circulatory changes in healthy older men. Circulation 100: 1085–1094, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blackwell KA, Sorenson JP, Richardson DM, Smith LA, Suda O, Nath K, Katusic ZS. Mechanisms of aging-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: role of tetrahydrobiopterin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2448–H2453, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Spiegelhalter DJ, Georgakopoulos D, Robinson J, Deanfield JE. Aging is associated with endothelial dysfunction in healthy men years before the age-related decline in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 24: 471–476, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cseko C, Bagi Z, Koller A. Biphasic effect of hydrogen peroxide on skeletal muscle arteriolar tone via activation of endothelial and smooth muscle signaling pathways. J Appl Physiol 97: 1130–1137, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res 90: 1159–1166, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delp MD, Behnke BJ, Spier SA, Wu G, Muller-Delp JM. Ageing diminishes endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and tetrahydrobiopterin content in rat skeletal muscle arterioles. J Physiol 586: 1161–1168, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dikalov SI, Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Schmidt HH, Harrison DG, Griendling KK. Distinct roles of Nox1 and Nox4 in basal and angiotensin II-stimulated superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production. Free Radic Biol Med 45: 1340–1351, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Levy AS, Pierce GL, Gates PE, Seals DR. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circ Res 100: 1659–1666, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Bailey DM, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: effects of antioxidants and exercise training in elderly men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H671–H678, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Nishiyama S, Lawrenson L, Richardson RS. Differential effects of aging on limb blood flow in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H272–H278, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drinkwater BL, Horvath SM, Wells CL. Aerobic power of females, ages 10 to 68. J Gerontol 30: 385–394, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Durrant JR, Seals DR, Connell ML, Russell MJ, Lawson BR, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA. Voluntary wheel running restores endothelial function in conduit arteries of old mice: direct evidence for reduced oxidative stress, increased superoxide dismutase activity and down-regulation of NADPH oxidase. J Physiol 587: 3271–3285, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eskurza I, Monahan KD, Robinson JA, Seals DR. Effect of acute and chronic ascorbic acid on flow-mediated dilatation with sedentary and physically active human ageing. J Physiol 556: 315–324, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eskurza I, Myerburgh LA, Kahn ZD, Seals DR. Tetrahydrobiopterin augments endothelium-dependent dilatation in sedentary but not in habitually exercising older adults. J Physiol 568: 1057–1065, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heumuller S, Wind S, Barbosa-Sicard E, Schmidt HH, Busse R, Schroder K, Brandes RP. Apocynin is not an inhibitor of vascular NADPH oxidases but an antioxidant. Hypertension 51: 211–217, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inbar O, Oren A, Scheinowitz M, Rotstein A, Dlin R, Casaburi R. Normal cardiopulmonary responses during incremental exercise in 20- to 70-yr-old men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26: 538–546, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Irion GL, Vasthare US, Tuma RF. Age-related change in skeletal muscle blood flow in the rat. J Gerontol 42: 660–665, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacobson A, Yan C, Gao Q, Rincon-Skinner T, Rivera A, Edwards J, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D. Aging enhances pressure-induced arterial superoxide formation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1344–H1350, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jasperse JL, Laughlin MH. Vasomotor responses of soleus feed arteries from sedentary and exercise-trained rats. J Appl Physiol 86: 441–449, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson DK, Schillinger KJ, Kwait DM, Hughes CV, McNamara EJ, Ishmael F, O'Donnell RW, Chang MM, Hogg MG, Dordick JS, Santhanam L, Ziegler LM, Holland JA. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation in endothelial cells by ortho-methoxy-substituted catechols. Endothelium 9: 191–203, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kang LS, Reyes RA, Muller-Delp JM. Aging impairs flow-induced dilation in coronary arterioles: role of NO and H2O2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1087–H1095, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirby BS, Voyles WF, Simpson CB, Carlson RE, Schrage WG, Dinenno FA. Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and exercise hyperaemia in ageing humans: impact of acute ascorbic acid administration. J Physiol 587: 1989–2003, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuo L, Chilian WM, Davis MJ. Interaction of pressure- and flow-induced responses in porcine coronary resistance vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1706–H1715, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lakatta EG. Cardiovascular system. In: Handbook of Physiology. Aging. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Sock, 1995, p. 413–474. [Google Scholar]

- 27. LeBlanc AJ, Shipley RD, Kang LS, Muller-Delp JM. Age impairs Flk-1 signaling and NO-mediated vasodilation in coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2280–H2288, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meyer JW, Holland JA, Ziegler LM, Chang MM, Beebe G, Schmitt ME. Identification of a functional leukocyte-type NADPH oxidase in human endothelial cells :a potential atherogenic source of reactive oxygen species. Endothelium 7: 11–22, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miller AA, Drummond GR, Schmidt HH, Sobey CG. NADPH oxidase activity and function are profoundly greater in cerebral versus systemic arteries. Circ Res 97: 1055–1062, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morikawa K, Shimokawa H, Matoba T, Kubota H, Akaike T, Talukder MA, Hatanaka M, Fujiki T, Maeda H, Takahashi S, Takeshita A. Pivotal role of Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase in endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization. J Clin Invest 112: 1871–1879, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muller-Delp JM, Spier SA, Ramsey MW, Delp MD. Aging impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation in rat skeletal muscle arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1662–H1672, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Musch TI, Eklund KE, Hageman KS, Poole DC. Altered regional blood flow responses to submaximal exercise in older rats. J Appl Physiol 96: 81–88, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ogawa T, Spina RJ, Martin WH, 3rd, Kohrt WM, Schechtman KB, Holloszy JO, Ehsani AA. Effects of aging, sex, and physical training on cardiovascular responses to exercise. Circulation 86: 494–503, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Proctor DN, Koch DW, Newcomer SC, Le KU, Leuenberger UA. Impaired leg vasodilation during dynamic exercise in healthy older women. J Appl Physiol 95: 1963–1970, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Proctor DN, Shen PH, Dietz NM, Eickhoff TJ, Lawler LA, Ebersold EJ, Loeffler DL, Joyner MJ. Reduced leg blood flow during dynamic exercise in older endurance-trained men. J Appl Physiol 85: 68–75, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reid MB. Nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, and skeletal muscle contraction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 371–376, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Richardson RS, Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Lawrenson L, Nishiyama S, Bailey DM. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: role of free radicals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1516–H1522, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Selemidis S, Sobey CG, Wingler K, Schmidt HH, Drummond GR. NADPH oxidases in the vasculature: molecular features, roles in disease and pharmacological inhibition. Pharmacol Ther 120: 254–291, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Setty BN, Jurek E, Ganley C, Stuart MJ. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on vascular arachidonic acid metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot Med 14: 205–213, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sindler AL, Delp MD, Reyes R, Wu G, Muller-Delp JM. Effects of ageing and exercise training on eNOS uncoupling in skeletal muscle resistance arterioles. J Physiol 587: 3885–3897, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith AR, Visioli F, Frei B, Hagen TM. Age-related changes in endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and nitric oxide dependent vasodilation: evidence for a novel mechanism involving sphingomyelinase and ceramide-activated phosphatase 2A. Aging Cell 5: 391–400, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith AR, Visioli F, Hagen TM. Plasma membrane-associated endothelial nitric oxide synthase and activity in aging rat aortic vascular endothelia markedly decline with age. Arch Biochem Biophys 454: 100–105, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soucy KG, Ryoo S, Benjo A, Lim HK, Gupta G, Sohi JS, Elser J, Aon MA, Nyhan D, Shoukas AA, Berkowitz DE. Impaired shear stress-induced nitric oxide production through decreased NOS phosphorylation contributes to age-related vascular stiffness. J Appl Physiol 101: 1751–1759, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spier SA, Delp MD, Meininger CJ, Donato AJ, Ramsey MW, Muller-Delp JM. Effects of ageing and exercise training on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and structure of rat skeletal muscle arterioles. J Physiol 556: 947–958, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stolk J, Hiltermann TJ, Dijkman JH, Verhoeven AJ. Characteristics of the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils by apocynin, a methoxy-substituted catechol. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 11: 95–102, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Ghiadoni L, Gennari A, Fasolo CB, Sudano I, Salvetti A. Aging and endothelial function in normotensive subjects and patients with essential hypertension. Circulation 91: 1981–1987, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanguy S, Boucher F, Toufektsian MC, Besse S, de Leiris J. Aging exacerbates hydrogen peroxide-induced alteration of vascular reactivity in rats. Antioxid Redox Signal 2: 363–368, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thengchaisri N, Hein TW, Wang W, Xu X, Li Z, Fossum TW, Kuo L. Upregulation of arginase by H2O2 impairs endothelium-dependent nitric oxide-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 2035–2042, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thomas SR, Chen K, Keaney JF., Jr Hydrogen peroxide activates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase through coordinated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 6017–6024, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Trott DW, Gunduz F, Laughlin MH, Woodman CR. Exercise training reverses age-related decrements in endothelium-dependent dilation in skeletal muscle feed arteries. J Appl Physiol 106: 1925–1934, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ungvari Z, Orosz Z, Labinskyy N, Rivera A, Xiangmin Z, Smith K, Csiszar A. Increased mitochondrial H2O2 production promotes endothelial NF-kappaB activation in aged rat arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H37–H47, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, Palacios-Callender M, Erusalimsky JD, Quaschning T, Malinski T, Gygi D, Ullrich V, Luscher TF. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med 192: 1731–1744, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Williams DA, Segal SS. Feed artery role in blood flow control to rat hindlimb skeletal muscles. J Physiol 463: 631–646, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH. Aging induces muscle-specific impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in skeletal muscle feed arteries. J Appl Physiol 93: 1685–1690, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH. Selected Contribution: Aging impairs nitric oxide and prostacyclin mediation of endothelium-dependent dilation in soleus feed arteries. J Appl Physiol 95: 2164–2170, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH. Shear stress induces eNOS mRNA expression and improves endothelium-dependent dilation in senescent soleus muscle feed arteries. J Appl Physiol 98: 940–946, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Woodman CR, Trott DW, Laughlin MH. Short-term increases in intraluminal pressure reverse age-related decrements in endothelium-dependent dilation in soleus muscle feed arteries. J Appl Physiol 103: 1172–1179, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang YM, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D. eNOS uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction in aged vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1829–H1836, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zafari AM, Ushio-Fukai M, Akers M, Yin Q, Shah A, Harrison DG, Taylor WR, Griendling KK. Role of NADH/NADPH oxidase-derived H2O2 in angiotensin II-induced vascular hypertrophy. Hypertension 32: 488–495, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhou X, Bohlen HG, Unthank JL, Miller SJ. Abnormal nitric oxide production in aged rat mesenteric arteries is mediated by NAD(P)H oxidase-derived peroxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H2227–H2233, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]