Abstract

This study evaluates a therapy for infarct modulation and acute myocardial rescue and utilizes a novel technique to measure local myocardial oxygenation in vivo. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) were targeted to the heart with peri-infarct intramyocardial injection of the potent EPC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF). Myocardial oxygen pressure was assessed using a noninvasive, real-time optical technique for measuring oxygen pressures within microvasculature based on the oxygen-dependent quenching of the phosphorescence of Oxyphor G3. Myocardial infarction was induced in male Wistar rats (n = 15) through left anterior descending coronary artery ligation. At the time of infarction, animals were randomized into two groups: saline control (n = 8) and treatment with SDF (n = 7). After 48 h, the animals underwent repeat thoracotomy and 20 μl of the phosphor Oxyphor G3 was injected into three areas (peri-infarct myocardium, myocardial scar, and remote left hindlimb muscle). Measurements of the oxygen distribution within the tissue were then made in vivo by applying the end of a light guide to the beating heart. Compared with controls, animals in the SDF group exhibited a significantly decreased percentage of hypoxic (defined as oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr) peri-infarct myocardium (9.7 ± 6.7% vs. 21.8 ± 11.9%, P = 0.017). The peak oxygen pressures in the peri-infarct region of the animals in the SDF group were significantly higher than the saline controls (39.5 ± 36.7 vs. 9.2 ± 8.6 Torr, P = 0.02). This strategy for targeting EPCs to vulnerable peri-infarct myocardium via the potent chemokine SDF-1α significantly decreased the degree of hypoxia in peri-infarct myocardium as measured in vivo by phosphorescence quenching. This effect could potentially mitigate the vicious cycle of myocyte death, myocardial fibrosis, progressive ventricular dilatation, and eventual heart failure seen after acute myocardial infarction.

Keywords: stem cell, phosphorescence lifetime measurements, oxygenation, vasculogenesis, heart failure

more than 7 million men and women suffer from myocardial infarction (MI) in the United States annually (38). This places them at risk to undergo the vicious cycle of diminished myocardial efficiency leading to progressive ventricular dilatation with loss of elliptical geometry, leading to even worse myocardial efficiency and an eventual loss of myocardial function, resulting in heart failure. Current treatment for heart failure consists of pharmacological optimization and limited revascularization, reconstructive, or replacement options. These modalities are highly effective for only a fraction of patients and do not address the significant microvascular deficiencies that persist even when an occluded artery is stented or bypassed. Endogenous machinery to repair injured and ischemic myocardium is inadequate, and tremendous resources have been devoted to developing molecular therapies that enhance both the microvascular perfusion and the function of ischemic or infarcted myocardium.

Therapeutic vasculogenesis, the de novo formation of microvasculature, is a potential therapeutic strategy to enhance myocardial perfusion and reverse cellular ischemia, both of which are associated with decreased fibrosis, prevention of adverse ventricular remodeling, and enhancement of myocardial energetics and function(1, 16, 17, 47). Endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) are bone marrow-derived pluripotent vascular precursor cells with the intrinsic ability to mature into blood vessels.(36). They may provide a molecular means of enhancing myocardial microvascular perfusion in patients without alternate revascularization options (18) and have been shown to augment both myocardial performance and histological vessel density (2, 47). Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF) is among the most potent and specific EPC cytokines. Its sole target is the CXCR4 cell surface antigen expressed in significant levels on CD34+ EPCs, and expression of this receptor is related to efficient SDF-induced transendothelial migration (23). In this study we have tested whether intramyocardial delivery of SDF as a highly specific and localized chemotactic signal for EPCs can improve myocardial perfusion and oxygenation, and reverse peri-infarct ischemia.

In addition, we utilize a novel technique to demonstrate the neovasculogenic properties of this cytokine-based EPC therapy. Myocardial oxygen pressure was assessed using a noninvasive, real-time optical technique for measuring oxygen pressures within microvasculature based on the oxygen-dependent quenching of the phosphorescence of Oxyphor G3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal care and biosafety.

Male adult Lewis rats (250–300 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Boston, MA). Food and water were provided ad libitum. The protocol utilized in this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania and conforms with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23).

Induction of heart failure.

Male Lewis rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg), endotracheally intubated with a 14-gauge angiocatheter, and mechanically ventilated (Hallowell EMC, Pittsfield, MA) with 0.5% isoflurane maintenance anesthesia. A left thoracotomy was performed via the fourth interspace, the pericardium was entered, and the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was encircled with a 7-0 prolene suture at the level of the left atrial appendage. The suture was briefly snared to verify isolation of the LAD and tied. This procedure ligated the LAD and induced an anterolateral infarction of ∼40% of the left ventricle (21). Immediately following LAD ligation the animals were randomized to two groups: saline control or therapy with SDF. The saline group received a total of 250 μl saline into five predetermined peri-infarct regions via direct intramyocardial injection with a 30-gauge needle. The treatment group received 3 μg/kg recombinant SDF-1α (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), diluted in saline for a total volume of 250 μl, via direct intramyocardial injection into the same five predetermined peri-infarct border-zone regions. The border zone was defined as one high-power field lateral to the myocardial scar (14). In addition, to upregulate bone marrow cell production, the treatment group received a subcutaneous injection of 40 μg/kg liquid sargramostim [recombinant granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)], diluted in saline for a total volume of 200 μl intraoperatively and on postoperative day 1. The saline group received 200 μl subcutaneous saline intraoperatively and on postoperative day 1. The thoracotomy was closed in three layers over a temporary thoracotomy tube, and the animals were allowed to recover. We did not include a control group that received only subcutaneous injections of GM-CSF because the preponderance of the literature has demonstrated no difference between control groups receiving intramyocardial saline injection only or groups receiving saline injection plus subcutaneous GM-CSF (2, 3, 12, 47).

This model of ischemic heart failure has been highly reproducible and previously published (8, 21, 47). At the 48-h time point following initial LAD ligation, oxygen tissue pressure from peri-infarct myocardium, myocardial scar, and remote left hindlimb muscle was characterized in vivo.

Oxygen histograms obtained by oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence.

Po2 histograms can be obtained from a single-point measurement using oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence. For an excitation source and a phosphorescence detector (light guide tips), positioned on the surface of tissue and separated by distance d, the sampled volume will be a banana-like shaped region, formed by overlapping three-dimensional “globes” of diffuse light centered in front of the tip of the light guides (20). Different parts of the volume may contribute unequally to the signal due to the differences in the absorption and scattering coefficients for the excitation light and phosphorescence. For Oxyphor G3, the excitation light (635 nm) is more absorbed and scattered than is the phosphorescence (800 nm). As a result, volumes closer to the excitation source contribute more to the detected signal than those further from the source. Most of the detected signal comes from the banana-shaped volume (20).

When normal tissue is sampled, the measured distribution of Po2 does not depend on the positions of the excitation and emission light guides, because the measured volume is much larger than the individual vascular beds in the tissue. The 6-mm center-to-center of the positioning of light guides in the present studies was used in part to be sure that sampled volume was representative of the tissue as a whole.

Measurement of Po2 histograms.

Phosphorescence lifetime measurements were performed using a PMOD-5000 phosphorometer (Oxygen Enterprises, Philadelphia, PA) (40). The PMOD-5000 is a frequency domain instrument operating in the frequency range of 100–100,000 Hz. The measured phosphorescence lifetimes are independent of local phosphor concentration and insensitive to the presence of endogenous tissue fluorophores and chromophores. The excitation light was carried to the measurement site through one glass fiber bundle and the emission collected by another 3-mm-diameter glass fiber bundle (center-to-center distance of 6 mm). The emission was passed through a 695-nm long-pass glass filter (Schott glass) and detected by an avalanche photodiode (Hamamatsu). The resulting photocurrent was converted into voltage, amplified, digitized, and transferred to the computer for analysis.

In the present study, PMOD-5000 was used in multifrequency mode (40) to determine distributions of phosphorescence lifetimes. The lifetime distributions were used to calculate distributions of Po2 values, i.e., oxygen histograms (41, 43). The excitation light (maximum wavelength = 635 nm) was modulated by a waveform consisting of 37 sinusoids with equal amplitudes and frequencies ranging from 100 Hz to 38 kHz. The tips of the light guides were brought into contact with the myocardium, but care was taken not to apply pressure that might restrict flow in the surface blood vessels. The obtained signal was used to calculate the dependence of the phosphorescence amplitude and phase on the modulation frequency. The resulting phase/amplitude dependence was analyzed using the maximal entropy method (41) to yield the distribution of phosphorescence lifetimes. This distribution was converted into the distribution of Po2 in the sample, as described previously (40, 41). The basis for the conversion is the Stern-Volmer relationship:

| (1) |

where Io and To, are the phosphorescence intensities and lifetimes in the absence of oxygen, and I and T are the phosphorescence intensities and lifetimes at Po2, respectively. The quenching constant, kQ, is a second-order rate constant, describing the quenching of the excited state of the phosphor by oxygen. The values of To and kQ have been determined for Oxyphor G3 for the experimental conditions (temperature, etc., as appropriate).

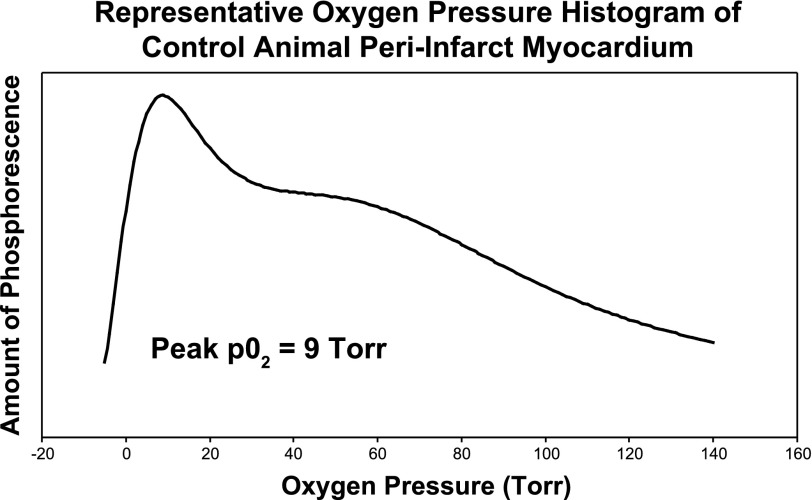

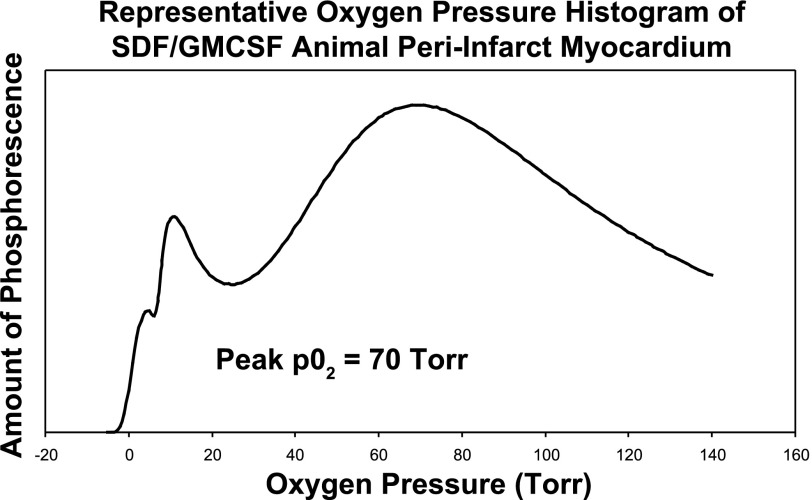

According to Eq. 1, intensities (amplitudes) of phosphorescent signals decrease with increasing Po2 values. Thus, for two equal volumes of tissue, containing equal amounts of the phosphorescent probe and excited by equal numbers of photons, the accuracy in signal is higher for lower Po2 values. The decrease in signal with increasing Po2 [decrease in signal-to-noise ratio (S/N)] results in asymmetric broadening of oxygen histograms, as seen in the “tail” effect on the high-oxygen end of the histogram. This asymmetric broadening is intrinsic to the analysis, reflecting the fact that uncertainty in determination of phosphorescence lifetimes increases with decreasing S/N. Thus, although the histograms are very reliable at lower Po2 values where there is little broadening, for Po2 values above ∼80 Torr, the histograms are sufficiently broadened; they should be used only for qualitative comparisons. The presented histograms were arbitrarily truncated at 140 Torr.

Phosphorescent probe: Oxyphor G3.

The phosphorescent probe, Oxyphor G3, based on a Pd-tetrabenzoporphyrin core, was used in our experiments (19).

Pd-tetrabenzoporphyrin dendrimer G3 has a polyarylglycine dendrimer composition and polyethyleneglycol surface coating. Oxyphor G3 (MW 16,100) is designed not to interact with albumin and other biomolecules by adding a surface layer of polyethyleneglycols. The dendrimer in G3 folds tightly around the core in aqueous media and controls accessibility of oxygen to the porphyrin. Oxyphor G3 has a quantum yield of ∼10% and a lifetime of ∼270 μs in deoxygenated aqueous solutions. The oxygen kQ of G3 in aqueous buffered solutions at pH 7.2 at 38°C is 180 Torr−1·s−1. Thus unbound Oxyphor G3 can be used to measure oxygen in physiological range. This value is well suited for oxygen measurements in vivo. Oxyphor G3 has a lifetime at zero oxygen of 270 μs.

The phosphorescence of Oxyphor G3 is insensitive to the presence of albumin (at 1–5% by weight range). It is also insensitive to changes in pH and ionic strength throughout the physiological range.

Measuring myocardial oxygen histograms.

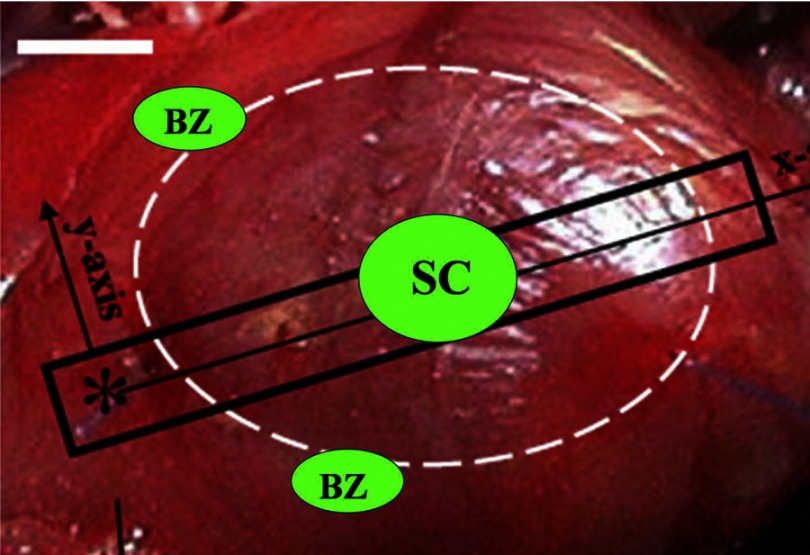

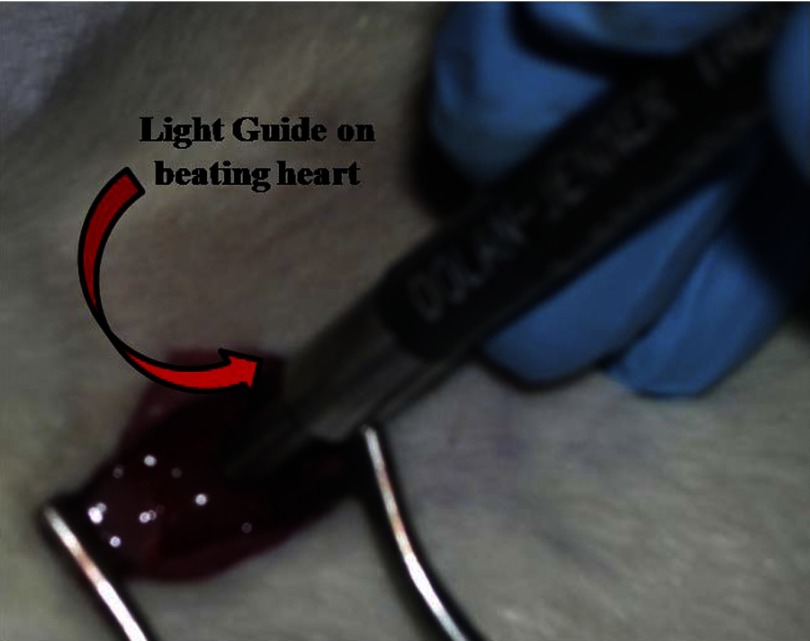

Forty-eight hours after coronary artery ligation and treatment, the rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and isoflurane (1.5% mixed with air), endotracheally intubated with a 14-gauge angiocatheter, mechanically ventilated (Hallowell EMC, Pittsfield, MA) with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 21% and 0.5% isoflurane maintenance anesthesia, and underwent redo left thoracotomy. They were then given injections of Oxyphor G3 solution (80 μM in physiological saline) in peri-infarct myocardium, myocardial scar, and remote left hindlimb muscle (Fig. 1). Injections consisted of ∼20 μl containing 1.6 nmol of Oxyphor per track using a 30-gauge needle. Two to three minutes was allowed to elapse between injection and measurement to help distribute the phosphor within the interstitial space of the myocardium, and then the oxygen histograms were measured in vivo on the beating heart (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of in vivo myocardial oxygen pressure measurements. Dashed white ellipse denotes infarcted LV. Asterisk indicates coronary ligation point. Green ellipses indicate typical sites of intramyocardial Oxyphor G3 injection and tissue oxygen pressure measurement. Remote left hindlimb muscle not pictured. BZ, border zone; SC, scar.

Fig. 2.

Measurement of oxygen histograms in vivo on the beating heart. The tips of the light guides were brought into contact with the myocardium, but care was taken not to apply pressure that might restrict flow in the surface blood vessels. The obtained signal was used to calculate the distribution of phosphorescence lifetimes which was subsequently converted into the distribution of Po2 in the sample.

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated using the unpaired Student's t-test for comparison between two means. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In vivo Po2 distributions in peri-infarct myocardium, myocardial scar, and remote left hindlimb muscle.

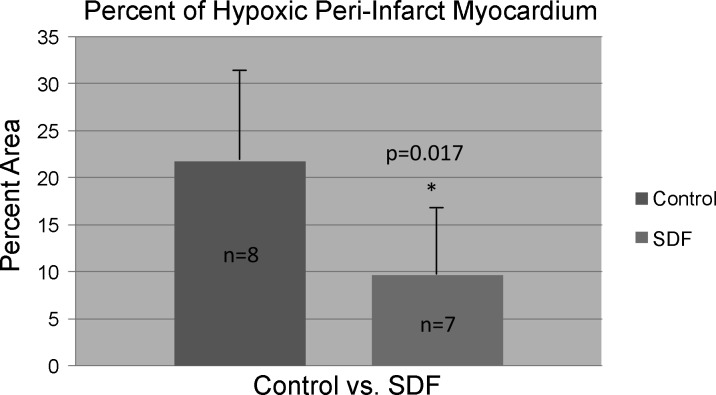

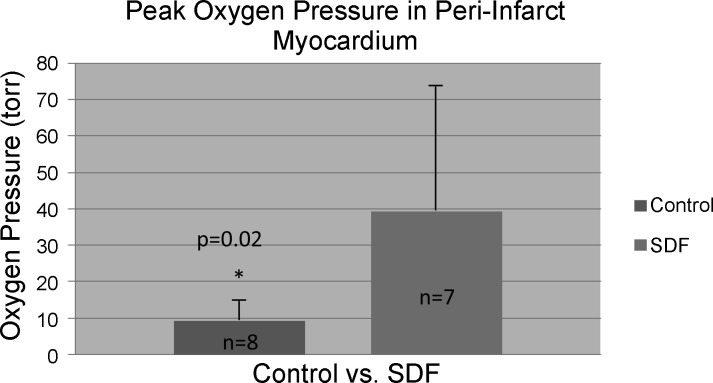

After injection of Oxyphor G3 into the muscle, there was a strong phosphorescence, which was not present before the phosphor was injected. Good S/N (typical values were from 65 to 120) was obtained using data collection periods of 200–600 ms. This allowed the measurements to be made quickly, minimizing sensitivity to movement of the contracting myocardium. Care was taken to avoid any torsion or pressure on the heart or remote leg muscle. This prevented mechanical occlusion of myocardial vasculature from yielding spurious hypoxic results. The light guides were brought gently in contact with the myocardium. The individual histograms were analyzed to determine the cumulative tissue volume fractions with an oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr. Compared with the saline control group, animals in the SDF group exhibited a significantly decreased percentage of hypoxic (defined as oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr) peri-infarct myocardium (9.7 ± 6.7% vs. 21.8 ± 11.9% of measured peri-infarct myocardium with oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr, P = 0.017) (Fig. 3). In addition, the peak oxygen pressures in the peri-infart region of the animals in the SDF group were significantly higher than the saline controls (39.5 ± 36.7 Torr vs. 9.2 ± 8.6 Torr, P = 0.02) (Fig. 4). Representative oxygen pressure histograms of both control and SDF-treated animals are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. The percent of hypoxic postinfarct myocardial scar (23.4 ± 15.8% vs. 20.5 ± 16.1% of measured myocardial scar with oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr, P = 0.364) and remote left hindlimb muscle (2.3 ± 2.4% vs. 7.2 ± 12.1% of measured hindlimb muscle with oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr, P = 0.158) did not differ significantly between the SDF-treated and saline control animals.

Fig. 3.

Compared with the saline control group, animals in the stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF) group exhibited a significantly decreased percentage of hypoxic peri-infarct myocardium (9.7 ± 6.7% vs. 21.8 ± 11.9% of measured peri-infarct myocardium with oxygen pressure ≤ 15.0 Torr, P = 0.017).

Fig. 4.

The peak oxygen pressures in the peri-infart region of the animals in the SDF/sargramostim [granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)] group were significantly higher than the saline controls (39.5 ± 36.7 Torr vs. 9.2 ± 8.6 Torr, P = 0.02).

Fig. 5.

Representative oxygen pressure histogram of control animal peri-infarct myocardium.

Fig. 6.

Representative oxygen pressure histogram of SDF-treated animal peri-infarct myocardium.

DISCUSSION

Stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF) is a powerful chemoattractant and considered to be one of the key regulators of hematopoietic stem cell trafficking between the peripheral circulation and bone marrow. It has been demonstrated to effect EPC proliferation and mobilization to induce vasculogenesis, and is significantly upregulated in response to both myocardial ischemia and infarction (24, 48). As a hard-working aerobic organ, the heart has to consume large amounts of O2 to support its primary contractile function, and the myocardial oxygen demand must not outstrip its supply if it is to maintain effective contractility. The myocardial oxygen extraction fraction {OEF = ([O2]artery − [O2]venous)/[O2]artery} reflects this balance in the heart (22). Current therapeutic options for ischemic heart disease are only capable of intervening in relatively large arteries, leaving pervasive microvascular dysfunction unaddressed. Even with reestablishment of epicardial coronary artery flow through thrombolysis, percutaneous intervention, or bypass grafting, there is still a paucity of patent, functional microvasculature and hence perfusion reaching the cardiomyocytes. This is important because microvascular integrity, specifically indices of microvascular blood velocity and flow, predicts functional recovery of ischemic myocardium (4, 6, 11, 28, 33). In this study, we were able to demonstrate that therapeutic post-myocardial infarction treatment with the potent vasculogenic cytokine SDF improves peri-infarct microvascular perfusion, leading to enhanced myocardial oxygenation. Experimentally, delivery of SDF to ischemic myocardium has been shown to significantly enhance myocardial endothelial progenitor cell density, increase microvasculature, and preserve ventricular geometry and function (2, 47). We theorize that it is this upregulation and targeting of endothelial progenitor cells to the ischemic border zone (and subsequent increase in microvascular blood delivery) that is the underlying mechanism for the observed increase in myocardial oxygen pressure.

In addition, we were also able to apply a novel technique for quantifying in vivo tissue oxygenation in real time from the surface of the heart. Oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence provides a direct optical method for determining Po2 values in biological and other samples (39, 45). This method has been shown to be effective for measurements in many types of biological media, including biological fluids and the microvasculature of tissue in vivo (5, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15, 25, 26, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 42, 46, 49). We used a specially designed new family of dendritic phosphors, whose periphery is modified with oligoethylene glycol fragments (27, 29, 30). Oxyphor G3 is one such oxygen sensor, and its oxygen-quenching properties are not affected by biological macromolecules such as albumin, while its phosphorescent parameters are well suited for measuring myocardial oxygen pressure in vivo (44). This technique is useful for determining the efficacy of experimental angiogenesis and has potential clinical applicability. The phosphorescent oxygen sensors, such as Oxyphor G3, might in principle be used during any open cardiac procedure to determine the viability of hibernating tissue, the success of revascularization, or to monitor reoxygenation of the ischemic myocardium on reperfusion.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant 1R01-HL-089315-01, “Angiogenic Tissue Engineering to Limit Post-Infarction Ventricular Remodeling,” (Y. J. Woo); NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/Thoracic Surgery Foundation for Research and Education jointly sponsored Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award 1K08-HL-072812, “Angiogenesis and Cardiac Growth as Heart Failure Therapy” (Y. J. Woo); The Thoracic Surgery Foundation Research Award (W. Hiesinger); and NIH Training Grant T32-HL-007843-13, “Training Program in Cardiovascular Biology and Medicine” (W. Hiesinger).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Assmus B, Schachinger V, Teupe C, Britten M, Lehmann R, Dobert N, Grunwald F, Aicher A, Urbich C, Martin H, Hoelzer D, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction (TOPCARE-AMI). Circulation 106: 3009–3017, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atluri P, Liao GP, Panlilio CM, Hsu VM, Leskowitz MJ, Morine KJ, Cohen JE, Berry MF, Suarez EE, Murphy DA, Lee WMF, Gardner TJ, Sweeney HL, Woo YJ. Neovasculogenic therapy to augment perfusion and preserve viability in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 81: 1728–1736, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atluri P, Panlilio CM, Liao GP, Hiesinger W, Harris DA, McCormick RC, Cohen JE, Jin T, Feng W, Levit RD, Dong N, Woo YJ. Acute myocardial rescue with endogenous endothelial progenitor cell therapy. Heart Lung Circ 19: 644–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balcells E, Powers ER, Lepper W, Belcik T, Wei K, Ragosta M, Samady H, Lindner JR. Detection of myocardial viability by contrast echocardiography in acute infarction predicts recovery of resting function and contractile reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 827–833, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behnke BJ, Kindig CA, Musch TI, Koga S, Poole DC. Dynamics of microvascular oxygen pressure across the rest-exercise transition in rat skeletal muscle. Respir Physiol 126: 53–63, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolognese L, Cerisano G, Buonamici P, Santini A, Santoro GM, Antoniucci D, Fazzini PF. Influence of infarct-zone viability on left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 96: 3353–3359, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buerk DG, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M, Johnson PC. Comparing tissue Po2 measurements by recessed microelectrode and phosphorescence quenching. Adv Exp Med Biol 454: 367–374, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatterjee S, Bish LT, Jayasankar V, Stewart AS, Woo YJ, Crow MT, Gardner TJ, Sweeney HL. Blocking the development of postischemic cardiomyopathy with viral gene transfer of the apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 125: 1461–1469, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dewhirst MW, Ong ET, Braun RD, Smith B, Klitzman B, Evans SM, Wilson D. Quantification of longitudinal tissue Po2 gradients in window chamber tumours: impact on tumour hypoxia. Br J Cancer 79: 1717–1722, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunphy I, Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. Oxyphor R2 and G2: phosphors for measuring oxygen by oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence. Anal Biochem 310: 191–198, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garot P, Pascal O, Simon M, Monin JL, Teiger E, Garot J, Gueret P, Dubois-Rande JL. Impact of microvascular integrity and local viability on left ventricular remodelling after reperfused acute myocardial infarction. Heart 89: 393–397, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hiesinger W, Frederick JR, Atluri P, McCormick RC, Marotta N, Muenzer JR, Woo YJ. Spliced stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha analog stimulates endothelial progenitor cell migration and improves cardiac function in a dose-dependent manner after myocardial infarction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 140: 1174–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang CC, Lajevardi NS, Tammela O, Pastuszko A, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, Wilson DF. Relationship of extracellular dopamine in striatum of newborn piglets to cortical oxygen pressure. Neurochem Res 19: 649–655, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jayasankar V, Bish LT, Pirolli TJ, Berry MF, Burdick J, Woo YJ. Local myocardial overexpression of growth hormone attenuates postinfarction remodeling and preserves cardiac function. Ann Thorac Surg 77: 2122–2129; discussion 2129, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson PC, Vandegriff K, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Effect of acute hypoxia on microcirculatory and tissue oxygen levels in rat cremaster muscle. J Appl Physiol 98: 1177–1184, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawamoto A, Gwon HC, Iwaguro H, Yamaguchi JI, Uchida S, Masuda H, Silver M, Ma H, Kearney M, Isner JM, Asahara T. Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation 103: 634–637, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kawamoto A, Tkebuchava T, Yamaguchi J, Nishimura H, Yoon YS, Milliken C, Uchida S, Masuo O, Iwaguro H, Ma H, Hanley A, Silver M, Kearney M, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T. Intramyocardial transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization of myocardial ischemia. Circulation 107: 461–468, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, Takuma S, Burkhoff D, Wang J, Homma S, Edwards NM, Itescu S. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med 7: 430–436, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lebedev AY, Cheprakov AV, Sakadzic S, Boas DA, Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA. Dendritic phosphorescent probes for oxygen imaging in biological systems. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 1: 1292–1304, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lev A, Sfez BG. Direct, noninvasive detection of photon density in turbid media. Opt Lett 27: 473–475, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu YH, Yang XP, Nass O, Sabbah HN, Peterson E, Carretero OA. Chronic heart failure induced by coronary artery ligation in Lewis inbred rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H722–H727, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCommis KS, O'Connor R, Lesniak D, Lyons M, Woodard PK, Gropler RJ, Zheng J. Quantification of global myocardial oxygenation in humans: initial experience. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 12: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mohle R, Bautz F, Rafii S, Moore MA, Brugger W, Kanz L. The chemokine receptor CXCR-4 is expressed on CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells and mediates transendothelial migration induced by stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood 91: 4523–4530, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pillarisetti K, Gupta SK. Cloning and relative expression analysis of rat stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1)1: SDF-1 alpha mRNA is selectively induced in rat model of myocardial infarction. Inflammation 25: 293–300, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poole DC, Behnke BJ, McDonough P, McAllister RM, Wilson DF. Measurement of muscle microvascular oxygen pressures: compartmentalization of phosphorescent probe. Microcirculation 11: 317–326, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Richmond KN, Shonat RD, Lynch RM, Johnson PC. Critical Po2 of skeletal muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1831–H1840, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rietveld I, Kim E, Vinogradov S. Dendrimers with tetrabenzoporphyrin cores: near infrared phosphors for in vivo oxygen imaging. Tetrahedron 59: 3821–3831, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rigo F, Varga Z, Di Pede F, Grassi G, Turiano G, Zuin G, Coli U, Raviele A, Picano E. Early assessment of coronary flow reserve by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography predicts late remodeling in reperfused anterior myocardial infarction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 17: 750–755, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rozhkov V, Wilson DF, Vinogradov S. Phosphorescent Pd porphyrin-dendrimers: tuning core accessibility by varying the hydrophobicity of the dendritic matrix. Macromolecules 35: 1991–1993, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rozhkov V, Wilson DF, Vinogradov S. Tuning oxygen quenching constants using dendritic encapsulation of phosphorescent Pd-porphyrins. Polymer Mater Sci Eng 85: 601–603, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rumsey WL, Pawlowski M, Lejavardi N, Wilson DF. Oxygen pressure distribution in the heart in vivo and evaluation of the ischemic “border zone”. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H1676–H1680, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rumsey WL, Vanderkooi JM, Wilson DF. Imaging of phosphorescence: a novel method for measuring oxygen distribution in perfused tissue. Science 241: 1649–1651, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimoni S, Frangogiannis NG, Aggeli CJ, Shan K, Quinones MA, Espada R, Letsou GV, Lawrie GM, Winters WL, Reardon MJ, Zoghbi WA. Microvascular structural correlates of myocardial contrast echocardiography in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction: implications for the assessment of myocardial hibernation. Circulation 106: 950–956, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shonat RD, Johnson PC. Oxygen tension gradients and heterogeneity in venous microcirculation: a phosphorescence quenching study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H2233–H2240, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shonat RD, Wilson D, Riva C, Pawlowski M. Oxygen distribution in the retinal and choroidal vessels of the cat as measured by a new phosphorescence imaging method. Appl Opt 31: 3711–3718, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simons M. Angiogenesis: where do we stand now? Circulation 111: 1556–1566, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sinaasappel M, Donkersloot C, van Bommel J, Ince C. Po2 measurements in the rat intestinal microcirculation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G1515–G1520, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, Zheng ZJ, Flegal K, O'Donnell C, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, Goff DC, Jr, Hong Y, Adams R, Friday G, Furie K, Gorelick P, Kissela B, Marler J, Meigs J, Roger V, Sidney S, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wilson M, Wolf P. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 113: e85–e151, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vanderkooi JM, Maniara G, Green TJ, Wilson DF. An optical method for measurement of dioxygen concentration based upon quenching of phosphorescence. J Biol Chem 262: 5476–5482, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vinogradov S, Fernandez-Seara M, Dugan B, Wilson DF. Frequency domain instrument for measuring phosphorescence lifetime distributions in heterogeneous samples. Rev Sci Instrum 72: 3396–3406, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vinogradov S, Wilson DF. Recursive maximum entropy algorithm and its application to the luminescence lifetime distribution recovery. Appl Spectrosc 54: 849–855, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vinogradov SA, Lo LW, Jenkins WT, Evans SM, Koch C, Wilson DF. Noninvasive imaging of the distribution in oxygen in tissue in vivo using near-infrared phosphors. Biophys J 70: 1609–1617, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. Phosphorescence lifetime analysis with a quadratic programming algorithm for determining quencher distributions in heterogeneous systems. Biophys J 67: 2048–2059, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilson DF, Lee WM, Makonnen S, Finikova O, Apreleva S, Vinogradov SA. Oxygen pressures in the interstitial space and their relationship to those in the blood plasma in resting skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 101: 1648–1656, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilson DF, Rumsey WL, Green TJ, Vanderkooi JM. The oxygen dependence of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation measured by a new optical method for measuring oxygen concentration. J Biol Chem 263: 2712–2718, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA, Grosul P, Vaccarezza MN, Kuroki A, Bennett J. Oxygen distribution and vascular injury in the mouse eye measured by phosphorescence-lifetime imaging. Appl Opt 44: 5239–5248, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Woo YJ, Grand TJ, Berry MF, Atluri P, Moise MA, Hsu VM, Cohen J, Fisher O, Burdick J, Taylor M, Zentko S, Liao G, Smith M, Kolakowski S, Jayasankar V, Gardner TJ, Sweeney HL. Stromal cell-derived factor and granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor form a combined neovasculogenic therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 130: 321–329, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamaguchi J, Kusano KF, Masuo O, Kawamoto A, Silver M, Murasawa S, Bosch-Marce M, Masuda H, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 effects on ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cell recruitment for ischemic neovascularization. Circulation 107: 1322–1328, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ziemer LS, Lee WM, Vinogradov SA, Sehgal C, Wilson DF. Oxygen distribution in murine tumors: characterization using oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence. J Appl Physiol 98: 1503–1510, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]