Abstract

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) are important for skeletal muscle function under both physiological and pathological conditions. ROS/RNS induce long-term and acute effects and the latter are the focus of the present review. Upon repeated muscle activation both oxygen and nitrogen free radicals likely increase and acutely affect contractile function. Although fluorescent indicators often detect only modest increases in ROS during repeated activation, there are numerous studies showing that manipulations of ROS can affect muscle fatigue development and recovery. Exposure of intact muscle fibres to the oxidant hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) affects mainly the myofibrillar function, where an initial increase in Ca2+ sensitivity is followed by a decrease. Experiments on skinned fibres show that these effects can be attributed to H2O2 interacting with glutathione and myoglobin, respectively. The primary RNS, nitric oxide (NO•), may also acutely affect myofibrillar function and decrease the Ca2+ sensitivity. H2O2 can oxidize the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channels. This oxidation has a large stimulatory effect on Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release of isolated channels, whereas it has little or no effect on the physiological, action potential-induced Ca2+ release in skinned and intact muscle fibres. Thus, acute effects of ROS/RNS on muscle function are likely to be mediated by changes in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity, which can contribute to the development of muscle fatigue or alternatively help counter it.

Graham Lamb (left) is based at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. His research background is in electrophysiology and muscle function, and he and his colleagues pioneered the use of skinned muscle fibres with functional excitation–contraction coupling for investigating muscle function in exercise and disease. He is currently a Research Fellow of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Håkan Westerblad (right) is professor in cellular muscle physiology at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. He and his colleagues developed techniques to study contractile function in isolated, intact fibres from mammalian skeletal muscle. A major focus of his research has been on cellular mechanisms of skeletal muscle fatigue.

|

It has become increasingly clear that reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) are of key importance for cellular function. In simplified terms one can say that modest and transient increases in ROS play essential roles in the normal cellular signalling, whereas large and prolonged increases occur in pathological conditions. ROS/RNS can induce long-term effects, which are mediated via altered gene and protein expression or via irreversible changes in existing proteins and lipids. They can also have more acute effects, which can be more or less fully reversible. In this short review we will discuss acutely occurring effects of ROS/RNS on the contractile function of skeletal muscle.

Muscle fibre contraction depends on the following sequence of events commonly referred to as excitation–contraction (EC) coupling. An action potential initiated at the neuromuscular junction propagates along the surface membrane of a muscle fibre and into the transverse tubular system, where it is sensed by specialised voltage sensor molecules, the dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs). Activation of the DHPRs triggers opening of the Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors, RyRs) in the adjacent sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which leads to a very rapid rise in cytoplasmic free [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i). Ca2+ then binds to the regulatory protein troponin C on the actin filament, which initiates cross-bridge cycling and contraction. Muscle fatigue is the term used to describe the decrease in muscle force or power that occurs with repeated muscle activation (Allen et al. 2008). Such decreased performance can be due to alterations or failure in one or more of the many steps involved in the EC-coupling sequence. Moreover, fatigue can be caused by many different factors, with the contribution of each depending on, for instance, the intensity and duration of the activation and the muscle fibre types involved (Allen et al. 2008). In this review we restrict our discussions to effects of ROS/RNS on isometric contractions and focus on studies where cellular mechanisms were assessed. In particular we consider the case of repeated muscle stimulation as a situation where an acute increase in ROS/RNS is likely to have important effects on contractile function, and discuss how this can involve not only adverse actions that hinder force production and exacerbate muscle fatigue, but also positive actions that help counter a decline in muscle performance.

ROS production during fatigue and its effect on force production

The primary oxygen free radical is the superoxide anion (O2−•). Among several tentative sources of superoxide in skeletal muscle, it appears to be mainly produced in the mitochondria as a by-product of oxidative phosphorylation and by NADPH oxidases (Allen et al. 2008; Powers & Jackson, 2008). Mitochondrial respiration increases during fatiguing stimulation and this supposedly results in increased O2−• production. Classically, the rate of mitochondrial O2−• production was believed to be 1–2% of the O2 consumption (Chance et al. 1979). However, for exercising skeletal muscle this must be a severe overestimation – if it were true, prolonged physical exercise (e.g. marathon running) would lead to lethally high ROS levels. Accordingly, more recent estimates of mitochondrial O2−• production provide markedly lower numbers, ∼0.15% of the O2 consumption (St-Pierre et al. 2002). Fatiguing stimulation may also increase ROS production by NAD(P)H oxidases especially in the triads, which may have functional consequences for the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release channels (the ryanodine receptor type 1, RyR1) (Hidalgo et al. 2006).

The primary nitrogen free radical is nitric oxide (NO•). NO• is synthesized from the amino acid l-arginine by nitric oxide synthases (NOS). In addition, it has recently been shown that NO• can be formed from the inorganic anions nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) (Lundberg & Weitzberg, 2010). The rate of NO• release from an isolated skeletal muscle increases with electrically stimulated contractions (Balon & Nadler, 1994). It might be argued that this increase was due to NO• production in other cell types in the muscle than the actual skeletal muscle fibres. However, more recently an increased rate of intracellular NO• production was also observed during electrical stimulation of isolated adult skeletal muscle fibres (Pye et al. 2007).

Various fluorescent indicators have been used to measure changes in ROS during fatiguing stimulation. Some studies have then shown increases in ROS in fatigue (e.g. Reid et al. 1992), whereas others have not detected any increase. For instance, the fluorescent indicator MitoSOX Red has been used to specifically assess mitochondrial ROS production and this indicator did not detect any increase in mitochondrial ROS during fatigue induced by repeated tetanic stimulation of isolated fast-twitch mouse muscle fibres (Aydin et al. 2009; Grundtman et al. 2010). On the other hand, MitoSOX Red detected a respiration-dependent increase in ROS when mitochondrial conversion of O2−• to H2O2 was inhibited by exposing cells to a high concentration of H2O2 (Fig. 1A). Moreover, a markedly increased MitoSOX Red fluorescence was observed in cardiomyocytes exposed to the saturated fatty acid palmitate (Fauconnier et al. 2007), which shows that the indicator can detect increased endogenous ROS production (Fig. 1B). A novel reversible redox sensitive green fluorescent protein construct targeted to mitochondria (mito-roGFP) was recently used to measure mitochondrial ROS production in isolated fast-twitch mouse muscle fibres (Michaelson et al. 2010). In agreement with the results obtained with MitoSOX Red, this indicator did not report any increased mitochondrial ROS production during fatigue induced by repeated tetanic stimulation. On the other hand, measurements with the general cytosolic ROS indicator dichlorofluorescein showed a small increase in the rate of ROS production during fatiguing stimulation (about twice the rate under resting conditions), which was attributed to activation of NAD(P)H oxidase (Michaelson et al. 2010).

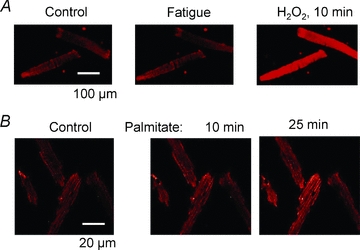

Figure 1. A fatigue-induced increase in ROS can be difficult to detect with fluorescent indicators.

A, confocal images of two isolated flexor digitorum brevis muscle fibres loaded with the mitochondrial ROS indicator MitoSOX Red. The fibres were fatigued by 100 tetanic contractions (70 Hz, 350 ms duration given at 2 s intervals) and this had no noticeable effect on the fluorescence signal (Control vs. Fatigue). The fibres were subsequently exposed to 100 μm H2O2, which gave a marked increase in fluorescence. Note that the H2O2-induced increase in fluorescence depends on mitochondrial respiration and is thus not a direct consequence of H2O2 interacting with the indicator (Aydin et al. 2009). B, confocal images of four MitoSOX Red-loaded cardiomyocytes obtained before (Control) and after exposure to the saturated fatty acid palmitate (1.2 mm). Note the marked increase in fluorescence induced by palmitate. Thus, MitoSOX Red can detect increased endogenous ROS production. Figure adapted from Fauconnier et al. (2007); ©2007 American Diabetes Association; from Diabetes, vol. 56, 2007; 1136–1142; reproduced by permission of The American Diabetes Association.

As discussed above, it can be difficult to detect changes in ROS during induction of fatigue in skeletal muscle. Does this mean that there are no functionally important increases in ROS production during fatiguing stimulation? The answer to this question is clearly no, since there are numerous studies demonstrating that ROS scavengers can delay fatigue development, although there are also many studies where no ROS dependency on fatigue development was observed (Powers & Jackson, 2008). A general trend is that where ROS effects on fatigue development are observed, they are generally more prominent with submaximal than with near-maximal contractions (Powers & Jackson, 2008). At the muscle cell level this indicates that ROS actions contributing to fatigue mainly affect the myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity and/or SR Ca2+ release, where changes have larger effects at submaximal than at near-maximal forces (see Fig. 6, Allen et al. 2008), and this will be discussed in greater detail below.

A dramatic effect of ROS was observed in a study where single mouse flexor digitorum brevis fibres were fatigued by repeated tetanic stimulation at increased temperature (37°C) (Moopanar & Allen, 2005). These fast-twitch fibres then showed a very rapid force decrease due to decreased myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity and this premature fatigue development was prevented by ROS scavengers. A subsequent study from the same laboratory showed that the premature fatigue development at increased temperature was caused by iron release from the heat exchanger and fatigue development was not accelerated at high temperature when iron was excluded from the bath solution (Reardon & Allen, 2009b). That study also showed that iron can increase ROS production in muscle cells, which explains the beneficial effect of ROS scavengers when iron was present during fatigue induced at increased temperature. Moreover, skeletal muscles of mice injected with iron show signs of increased ROS levels and impaired contractile function (Reardon & Allen, 2009a). Thus, these studies highlight the intricate interplay between different factors in the control of cellular ROS metabolism, which can have dramatic effects on muscle contractile function.

Studies from Westerblad's laboratory on fatigue in single mouse muscle fibres generally do not show any ROS-related change in fatigue development, whereas the recovery phase after fatiguing stimulation can be affected by ROS. For instance, in a recent study slow-twitch soleus fibres were fatigued under conditions of increased oxidative stress, i.e. increased temperature (43°C) and the presence of oxidizing peroxides (H2O2 or tert-butyl hydroperoxide) (Place et al. 2009). The force decrease during fatiguing stimulation was not affected by this oxidative stress, but fibres exposed to tert-butyl hydroperoxide went into contracture about 10 min after the end of fatiguing stimulation even when the peroxide had been removed. Another ROS dependency relates to prolonged low-frequency force depression (PLFFD), a long-lasting state frequently observed after fatiguing stimulation, in which submaximal force is decreased proportionately more than near-maximal force (Allen et al. 2008). In experiments on single fast-twitch fibres, the mechanism underlying PLFFD depended on the capacity of muscle fibres to convert O2−• to H2O2 via the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) (Bruton et al. 2008): PLFFD was due to decreased myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in rat fibres with higher SOD2 capacity and in mouse fibres overexpressing SOD2 (i.e. promoting accumulation of H2O2), whereas it was caused by decreased SR Ca2+ release in mouse fibres with relatively low SOD2 capacity (i.e. promoting accumulation of O2−•).

To sum up so far, numerous studies have shown an integral role of ROS for force production during fatigue and recovery, although there are also studies where no effects of ROS could be detected. When ROS effects are apparent they mainly involve changes in submaximal forces, which points to myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity and/or SR Ca2+ release as major targets and these will be discussed next.

Mechanisms by which ROS affect myofibrillar force production

In an initial series of experiments to reveal mechanisms whereby ROS acutely affects contractile function, intact mouse fast-twitch fibres were exposed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Andrade et al. 1998a). Application of H2O2 (100–300 μm) resulted in a transiently increased force production followed by a progressive force decrease, which could be reversed by the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT). Intriguingly, the opposite was also observed: exposure to dithiothreitol resulted in a progressive force decline that could be reversed by H2O2. Thus under these experimental conditions, the contractile function became severely impaired in both the oxidized and the reduced state and under normal resting conditions, muscle fibres were slightly on the reduced side of the optimal redox balance (Fig. 2).

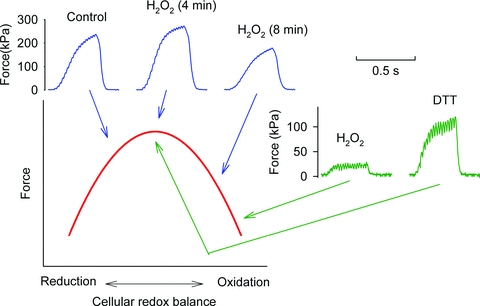

Figure 2. Submaximal force shows a redox maximum and decreases both with oxidation and reduction.

Force records from two experiments where submaximal tetani (50 Hz, 350 ms duration) were produced at ∼1 min intervals. One FDB fibre (blue lines) was first tested under control conditions and then exposed to H2O2 (300 μm), which resulted in an initial force increase followed by a decrease (4 and 8 min exposure, respectively). In another FDB fibre (green lines), the severe force depression induced by exposure to H2O2 (300 μm) was reversed by subsequent application of the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT, 1 mm). Note that [Ca2+]i remained basically unaffected by the exposures to H2O2 and DTT (not shown). The red line shows the schematic relationship between submaximal force and redox balance. Figure adapted from (Andrade et al. 1998a).

In studies on isolated intact muscle fibres, exposures to H2O2 and DTT affected mainly the myofibrillar function, where major changes in the Ca2+ sensitivity were observed, whereas SR Ca2+ release was little affected (Andrade et al. 1998a). A subsequent study with application of much lower concentrations of peroxides (down to 10−10m) also showed major effects on myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity (Andrade et al. 2001). These data are in accordance with results obtained during recovery from fatigue, which showed that when the endogenous formation of H2O2 was facilitated by a high SOD2 activity, PLFFD was due to decreased myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity (Bruton et al. 2008). Thus, both endogenously produced and exogenously applied H2O2 affect mainly the myofibrillar function. Conversely, accumulation of O2−• appears to exert its main effects on SR Ca2+ release (Bruton et al. 2008).

Identifying the molecular targets and precise mode of action of ROS in intact fibres is not straightforward, because these species readily transform into various derivatives, particularly when reacting with normal cellular constituents. Further information can be gleaned by examining the effects of such compounds on isolated proteins or systems, such as mechanically skinned muscle fibre preparations in which action potential-induced force responses are still functioning (Lamb, 2002).

In isolated contractile protein preparations and skinned fibres, H2O2 itself is relatively unreactive. Application of 10 mm H2O2 for 5 min causes no change in maximum force or the myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity (measured as the [Ca2+] at half-maximal force, Ca50), with the only change being a decrease in the steepness of the force–[Ca2+] relationship (Lamb & Posterino, 2003). Only with even higher or longer exposures to H2O2 are maximum force and Ca2+ sensitivity decreased, which is likely to be owing at least in part to oxidation-induced dysfunction of the myosin heads (Prochniewicz et al. 2008). In contrast, when myoglobin is also present, as it is in intact fibres, a 5 min exposure to lower H2O2 concentrations (100–300 μm) causes a large decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity (>35% increase in Ca50), with little change in maximum force (<5% decrease) (Murphy et al. 2008). This action is likely to be due to hydroxyl radicals (OH•) produced by the Fenton reaction when H2O2 interacts with Fe2+ in the haem core of myoglobin (Powers & Jackson, 2008). The additional presence of tempol, a SOD mimetic, was without effect, indicating that O2−• had no role in the action. The effects seen with combined H2O2-myoglobin treatment evidently involve oxidation of cysteine residues, because the effects are at least partially reversible with DTT, provided that the oxidized contractile proteins are not subjected to prolonged activation before applying this reducing agent (Murphy et al. 2008).

Glutathione (GSH) is a key cellular antioxidant and reducing agent that is present in the cytosol of intact skeletal muscle fibres at millimolar concentrations (Ji et al. 1992). To mimic the intracellular condition in skinned fibre experiments, GSH has to be added to the bath solution. If a relatively large amount of GSH (5 mm) is present when H2O2–myoglobin is applied to a skinned slow-twitch fibre, it prevents most of the decrease in force and Ca2+ sensitivity that otherwise occurs (Murphy et al. 2008). Notably, in skinned fast-twitch fibres, application of H2O2–myoglobin in the presence of GSH not only prevents the force decline but actually increases submaximal force due to an increased Ca2+ sensitivity (Murphy et al. 2008). This increase in Ca2+ sensitivity can be reversed by DTT treatment, and is evidently due to S-glutathionylation of particular cysteine residues on the contractile apparatus. It can be induced in fast-twitch fibres (but not in slow-twitch fibres) also by exposure to dithiodipyridine (DTDP, a highly reactive and specific sulphydryl reagent) followed by brief exposure to GSH (Lamb & Posterino, 2003). Such glutathionylation has no effect on maximum force but decreases the Ca50 by up to 1.7-fold, and this can be fully reversed by either DTT or prolonged exposure to GSH (Lamb & Posterino, 2003).

The above actions of OH• and GSH-related glutathionylation may account for the effects observed when exposing intact (fast-twitch) muscle fibres to H2O2 (∼10−4m) (Andrade et al. 1998a). The increase in Ca2+ sensitivity observed in intact fibres even at very low H2O2 (10−6m or less) (Andrade et al. 2001) would be expected if the large and highly sensitive glutathionylation effect occurred even to just a small extent (<20%), possibly brought about by H2O2 continually diffusing from the bathing solution into the fibre and irreversibly reacting with cellular constituents.

As discussed above, the effects of increased ROS on myofibrillar function, induced either endogenously during fatiguing stimulation or by exogenous application, involve mainly the sensitivity to Ca2+ whereas the maximum force is little affected. Changes in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity can, in principle, be due to (1) altered Ca2+ interaction with the actin filament regulatory troponin–tropomyosin protein complex, (2) changes to thick filament proteins such as the regulatory light chains, or (3) altered myosin cross-bridge function affecting the intricate interaction between cross-bridge attachment and actin filament activation (Gordon et al. 2000). The fact that maximum force generally is little affected by ROS argues against major effects on cross-bridge cycling as the mechanism underlying the changes in Ca2+ sensitivity. However, the actual molecular mechanisms underlying the myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity changes, and the reasons why only fast-twitch and not slow-twitch fibres show glutathionylation-related increases in Ca2+ sensitivity, remain to be identified.

To sum up, experiments on skinned fibres reveal that intracellular interactions between H2O2, myoglobin and GSH can explain both the initial increase in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity induced by exposure to exogenous H2O2 and the subsequent decreased sensitivity and this is illustrated in Fig. 3. This glutathionylation mechanism causing increased Ca2+ sensitivity in fast-twitch fibres may play a role in post-activation potentiation and counteract the decline in isometric and dynamic performance during fatiguing exercise (Rassier & Macintosh, 2000; MacIntosh et al. 2008).

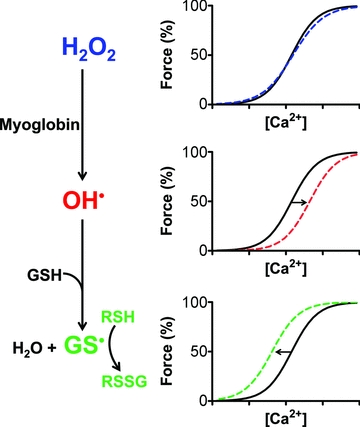

Figure 3. H2O2 can both decrease and increase the myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in skeletal muscle fibres.

H2O2 itself has only minor effects on the force response, but readily reacts with myoglobin to form OH•, which can decrease Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus by oxidising cysteine residues (RSH). This oxidation (labelled as RSox) might involve cysteine cross-linking or generation of species such as RSOH, RSO2H and RSO3H, the last of which is considered irreversible. Both OH• and H2O2 can react with GSH to generate thiyl radicals (GS·), which can S-glutathionylate a highly reactive cysteine residue (R1SH) in fast-twitch fibres, causing a large, reversible increase in Ca2+ sensitivity. The overall effect depends on the balance between glutathionylation, oxidation and reversal of oxidation by cytoplasmic GSH, and will change over time particularly if levels of reduced GSH decline.

In regard to the effect of RNS, experiments on intact fast-twitch muscle fibres have shown that exogenous NO• decreases the myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity (Andrade et al. 1998b). An increase in NO• during fatigue might then contribute to the decreased Ca2+ sensitivity consistently observed in fatigued fast-twitch muscle fibres (Westerblad & Allen, 1991). This is also observed in fast-twitch skinned fibres where the NO• donors S-nitroso-N-acetyl penicillamine (SNAP) and nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) cause decreased Ca2+ sensitivity (Ca50 increased by up to 30%) without any change in maximum force (Spencer & Posterino, 2009; Dutka et al. 2011b). This decrease in sensitivity is fully reversible with DTT. Interestingly, NO• donors did not affect the myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in slow-twitch fibres but the mechanism(s) underlying this difference remains uncertain (Spencer & Posterino, 2009).

It has been reported that the NO• donor nitroprusside (NP) reduces not only Ca2+ sensitivity but also maximum force (Perkins et al. 1997). Such an additional effect on maximum force may be due to NP also directly causing S-nitrosylation of the myosin heads and impaired cross-bridge function, as occurs with peroxynitrite (ONOO−) (Tiago et al. 2006; Dutka et al. 2011a) but not readily with NO• itself (Nogueira et al. 2009). Alternatively, as iron-based NP can generate Fenton chemistry products, these may have oxidized the myosin heads, thus decreasing force.

Little effect of ROS on action potential-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release

As mentioned earlier, the normal physiological process of SR Ca2+ release involves action potentials activating the transverse tubular voltage sensors (DHPRs), which in turn very potently activate the SR Ca2+ release channels (RyRs). Each of the steps in this process in theory might be affected by ROS. However, a general impairment of membrane excitability and action potential generation appears not to be a major weak link in the overall process, because intact muscle fibres exposed to ROS showed no evidence of action potential failure during tetanic stimulation (Andrade et al. 1998a, 2001) and action potential repriming is unaffected in skinned muscle fibres (Dutka et al. 2011b).

Experiments on isolated SR Ca2+ release channels have clearly established that they are readily oxidised by many agents and that this increases their sensitivity to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) (Marengo et al. 1998). Experiments with skinned fibres also show that oxidizing the release channels with H2O2 or DTDP greatly potentiates CICR and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (Lamb & Posterino, 2003; Posterino et al. 2003; Dutka et al. 2011b). Importantly, however, the amount of Ca2+ released by action potential stimulation in these skinned fibres was little if at all affected by such oxidation (Lamb & Posterino, 2003; Posterino et al. 2003), which is in agreement with the findings in intact fibres (Andrade et al. 1998a). These experiments show that the SR Ca2+ release channels are indeed sensitized by oxidation and that this potentiates Ca2+ release induced by submaximal depolarization (Posterino et al. 2003; Pouvreau & Jacquemond, 2005), but that the Ca2+ release to the normal physiological stimulus (action potentials) is little altered (Fig. 4). Furthermore, tetanic [Ca2+]i does not show any obvious ROS-dependent changes during fatiguing stimulation even under conditions with markedly increased ROS levels (Moopanar & Allen, 2005; Place et al. 2009). This indicates that the changes in action potential-induced SR Ca2+ release that occur during induction of fatigue are mediated by factors other than ROS (Allen et al. 2008).

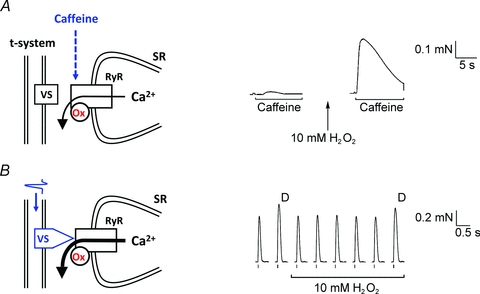

Figure 4. Oxidation of the RyRs results in increased caffeine-induced SR Ca2+ release, whereas the release triggered by action potentials is not affected.

A, oxidation of the RyRs in a skinned fibre by 5 min treatment with 10 mm H2O2 greatly potentiates Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and the response to caffeine (8 mm). B, In contrast, physiological Ca2+ release occurs when action potentials in the t-system trigger the voltage sensors (VS) to very potently activate the RyRs. In this situation Ca2+ release is little if at all affected by H2O2 treatment and RyR oxidation, and twitch responses to single and double pulse (D) stimulation remain virtually unchanged. Data reproduced from Posterino et al. (2003).

Experiments on intact muscle fibres show no change in submaximal tetanic force in response to NO• application and this was due to the decreased myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity induced by NO• being countered by increases in the SR Ca2+ release. This may reflect potentiation of action-potential induced Ca2+ release in intact fibres. Nitrosylation of isolated RyR does increase their sensitivity to CICR (Aracena et al. 2003), though it may also depress voltage-sensor induced SR Ca2+ release (Pouvreau & Jacquemond, 2005). The effect of NO• on RyR function may critically depend on the ambient O2 pressure and a fundamental role for the concerted action of NO• and O2 in the regulation of skeletal muscle contractility has been suggested (Eu et al. 2000, 2003). These authors then suggested that numerous in vitro studies of muscle function have been performed at supranormal O2 pressure, which would result in oxidative stress and altered contractile function. However, these controversial results and conclusions of Eu et al. have been questioned and when re-examined by other investigators, a critical role of O2 pressure on NO•-induced effects on RyR was not observed (Cheong et al. 2005). Moreover, studies on isolated muscle preparations are generally considered to be hampered by hypoxia rather than hyperoxia (Barclay, 2005).

Prolonged exposure to NO donors has been shown to increase the SR Ca2+ leak and resting cytosolic [Ca2+] in repeatedly stimulated voltage-clamped mouse FDB fibres (Pouvreau et al. 2004). This increase in resting SR Ca2+ leakage is likely to occur through nitrosylated RyRs (Aracena et al. 2003; Bellinger et al. 2009) and may contribute to the increase in resting [Ca2+]i observed in fatigued muscle fibres (Westerblad & Allen, 1991).

Conclusion

The findings of both intact fibre and skinned fibre experiments indicate that the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus in fast-twitch fibres is highly sensitive to ROS/RNS. This change in Ca2+ sensitivity is primarily responsible for the prominent acute effects of ROS/RNS on muscle performance, which can involve either potentiation or depression of the force responses. Conversely, the contractile apparatus of slow-twitch fibres is rather insensitive to acute ROS/RNS increases and this may contribute to the more stable force production in these fibres during challenges such as fatiguing stimulation. The SR Ca2+ release channels are also highly sensitive to ROS/RNS, but the acute changes in their responsiveness have comparatively little effect on normal (action potential-mediated) force responses. Increased or decreased responsiveness of the release channels nevertheless can, and likely does, exert important effects in the longer term, potentially changing the distribution of Ca2+ between different cellular sub-compartments and also chronically altering many Ca2+-dependent cellular processes. Of course, if ROS/RNS acutely were to reach extremely high levels globally or locally within a muscle fibre, they could be expected to exert numerous profound effects, including: (1) decreasing contractile apparatus function by effects on both maximum force and Ca2+ sensitivity, as may occur in some disease states; (2) disrupting the normal coupling between the voltage sensors and SR Ca2+ release channels, causing long-lasting decreases in muscle performance, as has been observed as PLFFD during the recovery phase after fatiguing exercise.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

cytoplasmic free [Ca2+]

- Ca50

[Ca2+] at half-maximal force

- CICR

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release

- DHPR

dihydropyridine receptor

- DTDP

dithiodipyridine

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GSH

glutathione

- GSNO

nitrosoglutathione

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NP

nitroprusside

- PLFFD

prolonged low-frequency force depression

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SNAP

S-nitroso-N-acetyl penicillamine

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

References

- Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:287–332. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol. 1998a;509:565–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.565bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of nitric oxide on single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol. 1998b;509:577–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.577bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade FH, Reid MB, Westerblad H. Contractile response of skeletal muscle to low peroxide concentrations: myofibrillar calcium sensitivity as a likely target for redox-modulation. FASEB J. 2001;15:309–311. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0507fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aracena P, Sanchez G, Donoso P, Hamilton SL, Hidalgo C. S-Glutathionylation decreases Mg2+ inhibition and S-nitrosylation enhances Ca2+ activation of RyR1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42927–42935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin J, Andersson DC, Hänninen SL, Wredenberg A, Tavi P, Park CB, Larsson NG, Bruton JD, Westerblad H. Increased mitochondrial Ca2+ and decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ in mitochondrial myopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:278–288. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balon TW, Nadler JL. Nitric oxide release is present from incubated skeletal muscle preparations. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:2519–2521. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ. Modelling diffusive O2 supply of isolated preparations of mammalian skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2005;26:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger AM, Reiken S, Carlson C, Mongillo M, Liu X, Rothman L, Matecki S, Lacampagne A, Marks AR. Hypernitrosylated ryanodine receptor calcium release channels are leaky in dystrophic muscle. Nat Med. 2009;15:325–330. doi: 10.1038/nm.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruton JD, Place N, Yamada T, Silva JP, Andrade FH, Dahlstedt AJ, Zhang SJ, Katz A, Larsson NG, Westerblad H. Reactive oxygen species and fatigue-induced prolonged low-frequency force depression in skeletal muscle fibres of rats, mice and SOD2 overexpressing mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:175–184. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong E, Tumbev V, Stoyanovsky D, Salama G. Effects of pO2 on the activation of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors by NO: a cautionary note. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutka TL, Mollica JP, Lamb GD. Differential effects of peroxynitrite on contractile protein properties in fast-and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers of rat. J Appl Physiol. 2011a;110(3):705–716. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00739.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutka TL, Mollica JP, Posterino GS, Lamb GD. Modulation of contractile apparatus Ca2+-sensivitivity and disruption of excitation-contraction coupling by S-nitrosoglutathione in rat muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2011b;589:2181–2196. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eu JP, Hare JM, Hess DT, Skaf M, Sun J, Cardenas-Navina I, Sun QA, Dewhirst M, Meissner G, Stamler JS. Concerted regulation of skeletal muscle contractility by oxygen tension and endogenous nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15229–15234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433468100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eu JP, Sun J, Xu L, Stamler JS, Meissner G. The skeletal muscle calcium release channel: coupled O2 sensor and NO signaling functions. Cell. 2000;102:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier J, Andersson DC, Zhang SJ, Lanner JT, Wibom R, Katz A, Bruton JD, Westerblad H. Effects of palmitate on Ca2+ handling in adult control and ob/ob cardiomyocytes: impact of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Diabetes. 2007;56:1136–1142. doi: 10.2337/db06-0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:853–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundtman C, Bruton J, Yamada T, Östberg T, Pisetsky DS, Harris HE, Andersson U, Lundberg IE, Westerblad H. Effects of HMGB1 on in vitro responses of isolated muscle fibers and functional aspects in skeletal muscles of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. FASEB J. 2010;24:570–578. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C, Sanchez G, Barrientos G, Aracena-Parks P. A transverse tubule NADPH oxidase activity stimulates calcium release from isolated triads via ryanodine receptor type 1 S-glutathionylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26473–26482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji LL, Fu R, Mitchell EW. Glutathione and antioxidant enzymes in skeletal muscle: effects of fiber type and exercise intensity. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1854–1859. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD. Excitation-contraction coupling and fatigue mechanisms in skeletal muscle: studies with mechanically skinned fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2002;23:81–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1019932730457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD, Posterino GS. Effects of oxidation and reduction on contractile function in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol. 2003;546:149–163. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.027896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. NO-synthase independent NO generation in mammals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh BR, Smith MJ, Rassier DE. Staircase but not posttetanic potentiation in rat muscle after spinal cord hemisection. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38:1455–1465. doi: 10.1002/mus.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo JJ, Hidalgo C, Bull R. Sulfhydryl oxidation modifies the calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels of excitable cells. Biophys J. 1998;74:1263–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77840-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson LP, Shi G, Ward CW, Rodney GG. Mitochondrial redox potential during contraction in single intact muscle fibers. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:522–529. doi: 10.1002/mus.21724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moopanar TR, Allen DG. Reactive oxygen species reduce myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in fatiguing mouse skeletal muscle at 37°C. J Physiol. 2005;564:189–199. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.083519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy RM, Dutka TL, Lamb GD. Hydroxyl radical and glutathione interactions alter calcium sensitivity and maximum force of the contractile apparatus in rat skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2008;586:2203–2216. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira L, Figueiredo-Freitas C, Casimiro-Lopes G, Magdesian MH, Assreuy J, Sorenson MM. Myosin is reversibly inhibited by S-nitrosylation. Biochem J. 2009;424:221–231. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins WJ, Han YS, Sieck GC. Skeletal muscle force and actomyosin ATPase activity reduced by nitric oxide donor. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1326–1332. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place N, Yamada T, Zhang SJ, Westerblad H, Bruton JD. High temperature does not alter fatigability in intact mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2009;587:4717–4724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posterino GS, Cellini MA, Lamb GD. Effects of oxidation and cytosolic redox conditions on excitation–contraction coupling in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2003;547:807–823. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouvreau S, Allard B, Berthier C, Jacquemond V. Control of intracellular calcium in the presence of nitric oxide donors in isolated skeletal muscle fibres from mouse. J Physiol. 2004;560:779–794. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouvreau S, Jacquemond V. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition affects sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle fibres from mouse. J Physiol. 2005;567:815–828. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SK, Jackson MJ. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1243–1276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochniewicz E, Lowe DA, Spakowicz DJ, Higgins L, O'Conor K, Thompson LV, Ferrington DA, Thomas DD. Functional, structural, and chemical changes in myosin associated with hydrogen peroxide treatment of skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C613–C626. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00232.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pye D, Palomero J, Kabayo T, Jackson MJ. Real-time measurement of nitric oxide in single mature mouse skeletal muscle fibres during contractions. J Physiol. 2007;581:309–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassier DE, Macintosh BR. Coexistence of potentiation and fatigue in skeletal muscle. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:499–508. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon TF, Allen DG. Iron injections in mice increase skeletal muscle iron content, induce oxidative stress and reduce exercise performance. Exp Physiol. 2009a;94:720–730. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.046045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon TF, Allen DG. Time to fatigue is increased in mouse muscle at 37°C: the role of iron and reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2009b;587:4705–4716. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MB, Haack KE, Franchek KM, Valberg PA, Kobzik L, West MS. Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. I. Intracellular oxidant kinetics and fatigue in vitro. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1797–1804. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Posterino GS. Sequential effects of GSNO and H2O2 on the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus of fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers from the rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1015–C1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00251.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Buckingham JA, Roebuck SJ, Brand MD. Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44784–44790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiago T, Simao S, Aureliano M, Martin-Romero FJ, Gutierrez-Merino C. Inhibition of skeletal muscle S1-myosin ATPase by peroxynitrite. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3794–3804. doi: 10.1021/bi0518500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H, Allen DG. Changes of myoplasmic calcium concentration during fatigue in single mouse muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1991;98:615–635. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]