Non-technical summary

Information is coded in the form of bursts of electrical impulses propagating among nerve cells which form complex networks in the brain. Effective communication between these cells depends on the ability for cross-talk among them through release and reception of chemical substances (neurotransmitters). This study uses the hearing system as a model to show that the patterns of electrical impulses can dramatically impact the amount of neurotransmitter released. When presented in short clusters, these impulses are more effective in releasing neurotransmitters than those composed of the same number of impulses but given continuously. Our findings may potentially help us understand how nerve cells code and transfer information in the mammalian brain, and in particular, how auditory neurons localize the sound source in space.

Abstract

Abstract

Patterns of action potentials (APs), often in the form of bursts, are critical for coding and processing information in the brain. However, how AP bursts modulate secretion at synapses remains elusive. Here, using the calyx of Held synapse as a model we compared synaptic release evoked by AP patterns with a different number of bursts while the total number of APs and frequency were fixed. The ratio of total release produced by multiple bursts to that by a single burst was defined as ‘burst-effect’. We found that four bursts of 25 stimuli at 100 Hz increased the total charge of EPSCs to 1.47 ± 0.04 times that by a single burst of 100 stimuli at the same frequency. Blocking AMPA receptor desensitization and saturation did not alter the burst-effect, indicating that it was mainly determined by presynaptic mechanisms. Simultaneous dual recordings of presynaptic membrane capacitance (Cm) and EPSCs revealed a similar burst-effect, being 1.58 ± 0.13 by Cm and 1.49 ± 0.05 by EPSCs. Reducing presynaptic Ca2+ influx by lowering extracellular Ca2+ concentration or buffering residual intracellular Ca2+ with EGTA inhibited the burst-effect. We further developed a computational model largely recapitulating the burst-effect and demonstrated that this effect is highly sensitive to dynamic change in availability of the releasable pool of synaptic vesicles during various patterns of activities. Taken together, we conclude that AP bursts modulate synaptic output mainly through intricate interaction between depletion and replenishment of the large releasable pool. This burst-effect differs from the somatic burst-effect previously described from adrenal chromaffin cells, which substantially depends on activity-induced accumulation of Ca2+ to facilitate release of a limited number of vesicles in the releasable pool. Hence, AP bursts may play an important role in dynamically regulating synaptic strength and fidelity during intense neuronal activity at central synapses.

Introduction

High-frequency AP bursts are characteristics of many neuronal populations (Kandel & Spencer, 1961; Ranck, 1973; Connors & Gutnick, 1990; Ramcharan et al. 2000; Lorteije et al. 2009; Sonntag et al. 2009). AP bursts could activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) and regenerative Ca2+ activity in dendritic compartments to induce plasticity mechanisms and affect dendritic integration properties during synaptic transmission (Larkum et al. 1999). Communication in the form of AP bursts, in addition to AP frequency, might be another important means for synapses to expand their coding capacity of information content (Lisman, 1997; Brezina et al. 2000; Sherman, 2001). Even in the same cell type, different neurotransmitters could be elicited by different stimulation patterns in the dorsal horn (Lever et al. 2001). By combining membrane capacitance (Cm) recording and Ca2+ measurement, we previously reported that AP patterns strongly modulate the somatic release in adrenal chromaffin cells via AP frequency (Zhou & Misler, 1995; Elhamdani et al. 1998) and bursts (Duan et al. 2003). For certain AP patterns, there is a ‘burst-effect’ in that the total secretion induced by ‘multi-short-bursts’ can be larger than that induced by a ‘single-long-burst’ with the same AP number and frequency (Duan et al. 2003). However, the Ca2+-dependent exocytosis from somatic chromaffin cells may be very different from that in presynaptic terminals where Ca2+-sensor types differ and the spatial couplings of VGCCs to vesicles are much tighter (Neher, 2006). Thus, how AP patterns modulate secretion at central synapses remains elusive.

Short-term changes in synaptic strength by burst activity are proposed to be mediated by presynaptic mechanisms such as Ca2+-dependent increase or decrease in release probability, depletion and replenishment of synaptic vesicles (SVs) (von Gersdorff & Borst, 2002; Zucker & Regehr, 2002). However, these conclusions are derived from postsynaptic recordings which may be complicated by postsynaptic modulations such as receptor desensitization and saturation. Taking advantage of the calyx of Held–medial nuclei of the trapezoid body (MNTB) synapse in the auditory brainstem where acoustic information is precisely conducted through AP bursts (Trussell, 1999; Sonntag et al. 2009), we performed paired voltage-clamp recordings from the distinct large presynaptic nerve terminal and postsynaptic principal neuron at this synapse (Forsythe, 1994; Borst et al. 1995; Takahashi et al. 1996). With this technique, SVs released from the presynaptic terminal can be readily quantified by presynaptic Cm which measures the amount of vesicle fusion, while EPSCs recorded from the postsynaptic neuron are obtained as another readout of neurotransmitter release (Sun et al. 2002). The simultaneous recordings of Cm and EPSCs provide an excellent experimental system to address the role of AP bursts in presynaptic exocytosis independent of postsynaptic factors.

In this study, we found that at the young calyx of Held synapse (postnatal day 8–10) the exocytotic output in presynaptic Cm evoked by AP trains paralleled that measured with EPSCs. Comparison of exocytotic output evoked by AP patterns in the form of single-long-burst versus multi-short-bursts revealed a distinct burst-effect that is strongly dependent on the rate of Ca2+-dependent depletion and replenishment of SVs in the fast pool at the calyx of Held terminal. Unlike the somatic release in chromaffin cells, the total output, however, was dominated by vesicle depletion, leading to the evenly distributed AP bursts having the highest efficacy in synaptic transmission.

Methods

Slice preparation

All procedures related to the handling of the mice (CD1 × C57 hybrid) in this study were approved by Peking University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Transverse brainstem slices were prepared from postnatal day (P) 8–10 mice, as described previously (Yang & Wang, 2006). Mice were decapitated with a small guillotine and the brains immediately dissected and immersed in ice-cold standard extracellular solution containing (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 sodium pyruvate, 3 myo-inositol, 0.5 ascorbic acid, 26 NaHCO3, 1 MgCl2, and 2 CaCl2 (pH 7.4, with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). For fibre stimulation, thicker slices (300 μm) were used to preserve afferent axons. For presynaptic or paired voltage-clamp recordings, thinner slices (150–200 μm) were prepared to minimize presynaptic axon length and reduce voltage-clamp errors. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Electrophysiology

Extracellular solution was supplemented with bicuculline (10 μm) and strychnine (1 μm) to block inhibitory inputs during recording. Patch electrodes were fabricated from glass with filaments and coated with dental wax. Resistance of these pipettes was 2–3 MΩ for postsynaptic neurons in fibre stimulation experiments. For paired voltage-clamp recordings, presynaptic and postsynaptic series resistances were <20 MΩ and <10 MΩ, respectively, and compensated to 70–90%. Cells showing higher resistances were omitted. The intracellular solution for presynaptic recording contained (in mm): 100 CsCl, 40 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 2 ATP, 0.5 GTP, 12 phosphocreatine, 20 TEA, 3 potassium glutamate, pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. Intracellular solution for postsynaptic recordings contained (in mm): 97.5 potassium gluconate, 32.5 CsCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 30 TEA, 1 QX314 (pH 7.2). The holding potential was −80 mV for presynaptic terminals and −60 mV for postsynaptic neurons. Presynaptic Cm measurements were performed using an EPC/9 amplifier (HEKA Electronic, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany) and the ‘Sine + DC’ technique (Lindau & Neher, 1988; Sun & Wu, 2001). A sine wave (20 mV in amplitude, 1000 Hz) was superimposed onto a holding potential of −80 mV at the presynaptic terminal. During fibre stimulation experiments, EPSCs from neurons in the MNTB were induced by electrical stimuli (0.2 ms, 3–10 V) via a bipolar electrode positioned close to the MNTB midline at room temperature (RT, 22–25°C) or near physiological temperature (PT, 33–36°C) and only recordings from neurons that responded reliably to 100 Hz stimulation were analysed. To assess the amount of glutamate release, we measured the cumulative charge transfer by integrating EPSCs evoked during the stimulation train. Slow build-up currents during repetitive activity, largely accounted for by synaptic spillover currents arising from glutamate trapping and rebinding (Wang et al. 2008), were subtracted by adjusting baseline to only integrate the area of each EPSC.

Simulation

The simulation included two parts: (1) simulation of the profile of AP-induced Ca2+ domain ([Ca2+]i) at the release site, and (2) [Ca2+]i-dependent vesicle release signal (Cm).

-

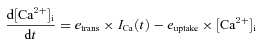

Simulation of the profile of AP-induced [Ca2+]i at the release site. At the calyx of Held, it is not possible to directly measure the [Ca2+]i at the vesicle release site. However, the [Ca2+]i can be estimated by assuming that the profile of local [Ca2+]i is proportional to the profile of AP-induced Ca2+ current. For this, we recorded an AP waveform from a P9 calyx under current clamp with afferent fibre stimulation (Fig. 6A; also see Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005), and calculated the influx of Ca2+ ions through a VGCC with the AP waveform using the Hodgkin–Huxley m2 model (Borst & Sakmann, 1998). At the calyx of Held, release sites are very close to Ca2+ channels to sense local [Ca2+]i increase during an AP, which is far higher than the residual [Ca2+]i (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Wang et al. 2008). For simplicity of the simulation, we assumed that local [Ca2+]i is determined only by Ca2+ influx and its local diffusion near Ca2+ channels during an AP. Thus, during an AP, we converted Ca2+ influx to a local [Ca2+]i concentration according to the following equation described previously (Sun et al. 2009):

(1) where etrans is an arbitrary transfer coefficient that scales Ca2+ influx to the local [Ca2+]i, and euptake is the rate constant of Ca2+ uptake. Assuming AP-induced [Ca2+]i transients are 27 μm in peak and 350 μs in half-width (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Wang et al. 2008), we simulated the profile of [Ca2+]i in response to an AP stimulation in the extracellular solution containing 2 mm Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o) and obtained euptake= 2 ms−1 and etrans= 0.0000575 μm nA−1 ms−1 (inset in Fig. 6A, see Table 1 for the parameters used in the simulation).

-

Simulation of [Ca2+]i-dependent vesicle release signal (Cm). The evoked vesicle release occurs from two independent pools: fast releasable pool (fRP) and slow releasable pool (sRP). The two pools have fixed resting sizes and can be released by APs and replenished from an infinite pool (Vinfinite) with their distinct time constants (see Table 2). Those pools are characterized by four parameters: their initial pool sizes Sf (for fRP) and Ss (for sRP), and their recovery time constants τf and τs. The two pool sizes are known to be the same (Sf=Ss, Neher, 2006). τf is known to be dependent on residual [Ca2+]i (Hosoi et al. 2007). However, for simplicity we did not include this Ca2+ dependence in our simulation (the effect of residual [Ca2+]i on fRP replenishment and the burst-effect can be estimated, in part, by reducing τf in Fig. 6D). Vesicles of the two pools undergo Ca2+-dependent secretion processing according to the following five-site model (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Wang et al. 2008):

(2)

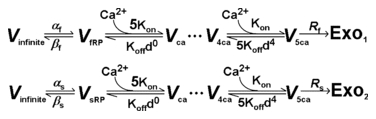

Figure 6. Simulation of burst-effect at the calyx of Held synapse.

A, averaged experimental Cm data (grey, n = 5) and simulated Cm (black) under the stimulation pattern [100, 100 Hz, b4 or b1, 1 s] (upper panels). Simulated AP-induced Ca2+ current was converted to the local [Ca2+]i with a peak of 27 μm[Ca2+]i (upper inset). Bottom traces illustrate the simulated temporal profile of the vesicles released from the fRP and sRP by different patterns of stimulation. Inset shows the expanded exocytosis and replenishment of the fRP and sRP. B–D, simulated γ[100, 100 Hz, b4/b1, 1 s] as a function of the peak of local [Ca2+]i at release site (arrow shows 27 μm[Ca2+]i during an AP in 2 mm[Ca2+]o) (B), size of the fRP and sRP (C), and changes in τf and τs (D) (arrows show the values obtained from A). E, relation between γ[b4/b1, i = 1 s] and δ/δc (relative distance between Ca2+ channel and release site with the unit of δc) in response to stimulation [100, 100 Hz, b4/b1, 1 s]. δc is 61 nm for P8–10 synapses.

Table 1.

Parameters used in simulation with HH m2 model for the time course of Ca2+ domain [Ca2+]i created by an AP (eqn (1)in Methods) as shown inFig. 6A

| Equation | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HH m2 equationa | ICa(t) =m2gmax(V−Vr) | gmax= 48.9 (nanosiemens) | Vr= 45 mV |

| dm/dt=αm(1 −m) −βmm | |||

| αm=α0exp(V/Vα) | α0= 1.78 ms−1 | Vα= 23.3 mV | |

| βm=β0exp(V/Vβ) | β0= 0.14 ms−1 | Vβ= 15 mV | |

| Peak [Ca2+]i at release siteb | 27 μm | ||

| Half-width of Ca2+ transientb | 350 μs |

ICa(t) is VGCC current. Other parameters refer to Borst & Sakmann, 1998.

The peak [Ca2+]i at the release site is 27 μm in 2 mm[Ca2+]o according to Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Wang et al. 2008.

Table 2.

Parameters estimated from the simulation of AP-induced Cm signals in Fig. 6A with eqn (2) in Methods, assuming Cm of a single vesicle is 0.065 fF (Sun et al. 2002), equal fRP and sRP (Sf=Ss) (Neher, 2006), and the release rate for fRP is 10 times faster than that for sRP

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Size of Vinfinite (vesicles) | 3.846 × 107 |

| Sf=Ss (vesicles) | 1538 |

| αf (ms−1) | 0.00000008 |

| βf (ms−1) | 0.002 |

| αs (ms−1) | 0.0000000005 |

| βs (ms−1) | 0.000125 |

| τf (s) | 8 |

| τs (s) | 0.5 |

The vesicle release process from fRP (upper) and sRP (lower) is constrained as follows. First, the factor determining the vesicle fusion rate (Rs) upon Ca2+ binding was set to 6000 ms−1 according to the fusion rate of a five-site model (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Wang et al. 2008) and the release rate of fRP (Rf) is 10 times faster than that of sRP (Rf= 10 ×Rs= 60,000 ms−1) (Neher, 2006). Then, Kon (13.6 × 107 μm−1 ms−1), Koff (11,100 ms−1) and the cooperativity factor, d (0.25), were fixed accordingly (Wang et al. 2008). Finally, the rate constants αf, βf, αs and βs determine the replenishment time constants (τf= 1/(αf+βf) and τs= 1/(αs+βs)). AP-induced Cm jumps and corresponding vesicle numbers (Exo1+ Exo2) were calculated given 0.065 fF vesicle-1 (Sun et al. 2002).

The programs for the non-linear differential equation were written and executed with the software CeL, based on the Markov algorithm and compiled with the C++ compiler to run under Windows XP, as described previously (Sun et al. 2009).

Data analysis

Data were acquired on-line, filtered at 2.9–4 kHz, digitized at 20–50 kHz and analysed off-line with Igor (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA), MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA) and Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical tests of significance were two-tailed paired or unpaired Student's t tests or one-way ANOVA with a P value cutoff <0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

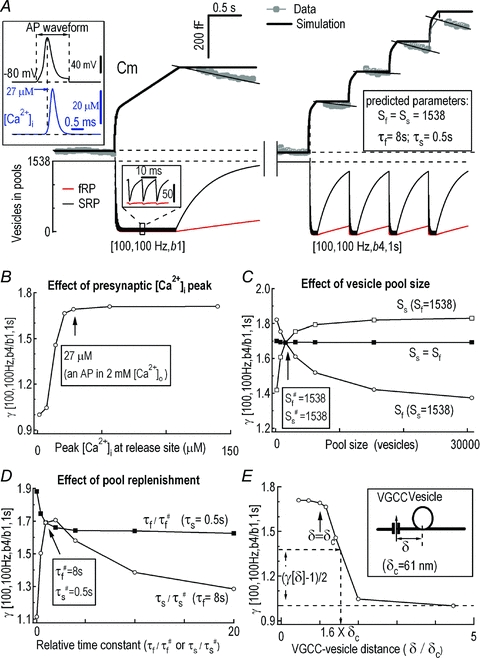

Transmitter release at the central synapse is modulated by AP burst patterns

The giant presynaptic calyx of Held contacts only one postsynaptic principal neuron which is readily visualized by differential interference contrast microscopy (Fig. 1A). To examine how complex AP patterns affect the total exocytotic output, we defined each AP pattern with four parameters [N, f, b, i] (‘AP codes’) (Duan et al. 2003), where N is the total number of Aps, f is the frequency in a burst, b is the number of bursts, and i is the interburst interval (Fig. 1B). For any given ‘primary codes’[N, f], we examined whether dividing a single long AP train into multiple short bursts with burst codes [b, i] affects the total synaptic output. In the first set of experiments, glutamatergic EPSCs were recorded from the MNTB principal neurons under whole-cell voltage-clamp while presynaptic axon bundles were stimulated with a bipolar electrode. We delivered stimulation trains at 100 Hz for 1 s (100 APs in total) and found that an initial AP-induced large EPSC (5.7 ± 0.6 nA, n = 13) rapidly declined to a depressed steady state after 6–10 APs. We defined the ratio of the amplitude of the tenth EPSC to that of the first one (EPSC10/EPSC1) as the depression level, and the estimated depression level was 0.15 ± 0.03 (n = 7, Fig. 1C inset). Such a depression fully recovered within 15 s, similar to a previous report (von Gersdorff et al. 1997). To quantify the total synaptic transmission (influx charge during the stimuli), EPSCs following stimulation were integrated and converted to EPSC charge (QEPSC), which took the summation of release in a period of time and reflected the total exocytotic output estimated from EPSCs. Given the primary codes [N = 100, f = 100 Hz] and interval time [i = 2 s], the single burst pattern produced QEPSC[b = 1] of 80 ± 10 pC, while the 4-short-burst pattern produced QEPSC[b = 4] of 124 ± 11 pC, revealing an increase in the ‘burst-effect’γ[b4/b1]= 1.47 ± 0.04 (n = 7, Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1. Burst-effect at the calyx of Held synapse revealed by EPSC recordings.

A, photomicrograph of MNTB principal neurons from a mouse brain slice. B, diagram of fibre stimulation with AP codes [N, f, b, i]. C, representative traces of EPSCs evoked by temporal pattern stimulations in the same cell: 100 pulses at 100 Hz with single burst stimulation (b = 1, left) [100, 100 Hz, b1], four bursts (b = 4, 25 pulses in each burst with interburst interval of 2 s, middle) [100, 100 Hz, b4, 2 s], and single burst stimulation (right) [100, 100 Hz, b1] with fibre stimulation. QEPSC was individual EPSCs integrated to estimate the output of cumulative release (bottom). QEPSC includes only the area under each EPSC, while slow build-up current during repetitive EPSCs was subtracted (see Methods). Inset shows the expanded first ten EPSCs in the first burst stimulation. Stimulation artifacts were removed. D, normalized QEPSC for single bursts or multiple short bursts as shown in C. Four-burst pattern [b = 4, 2 s] increased QEPSC by 147 ± 4% compared to single-burst pattern [b = 1, 2 s] (P < 0.001, n = 7, paired t test). Burst-effect γ[b4/b1] is the ratio of the synaptic output of patterns [b = 4]vs.[b = 1]. E, statistical summary of the burst-effect γ as a function of AP codes [N, f, b, i] in P8–10 mice. * indicates statistic significance (P < 0.05, t test) in this and the following figures.

To investigate how burst-effect γ[b4/b1] varies under a wide range of stimulation patterns [N, f, b, i], each parameter was changed while the others were fixed. Increasing stimulation number N (from 4 to 40, 100 and 400 APs) in patterns [f = 100 Hz, i = 2 s] decreased the burst-effect from γ[b4/b1] of 1.96 ± 0.16 to 1.63 ± 0.04, 1.47 ± 0.04 and 1.23 ± 0.02, respectively (P < 0.05, n = 7). Increasing burst frequency f (from 50 Hz to 100 Hz) in patterns [N = 100, i = 2 s] enhanced the burst-effect from γ[b4/b1] of 1.23 ± 0.02 to 1.47 ± 0.04 (P < 0.05, n = 7, paired t test). Increasing interburst interval i (from 2 s to 10 s) in patterns [N = 100, f = 100 Hz] potentiated the burst-effect from γ[b4/b1] of 1.47 ± 0.04 to 1.58 ± 0.1 (P < 0.05, n = 7, paired t test). Finally, increasing burst number b (from 2 to 4, 20) in patterns [N = 100, f = 100 Hz, i = 2 s] augmented the burst-effect from γ[b2/b1]= 1.21 ± 0.03 to [b4/b1]= 1.47 ± 0.04, [b20/b1]= 2.55 ± 0.13 (P < 0.001, n = 7, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 1E). Raising experimental temperature to near physiological conditions (33–36°C) increased the amplitude of EPSCs (RT: 5.7 ± 0.6 nA, n = 7, vs. PT: 11.1 ± 1.2 nA, n = 4), as shown previously (Yang & Wang, 2006). The burst-effect remained in spite of being less robust at higher temperature (γ[b4/b1]= 138 ± 4%, n = 7 at RT vs. (γ[b4/b1]= 116 ± 4%, n = 4 at PT) (data not shown). Therefore, the synaptic burst-effect was regulated by all of the four ‘coding parameters’ of AP patterns [N, f, b, i] as well as by temperature.

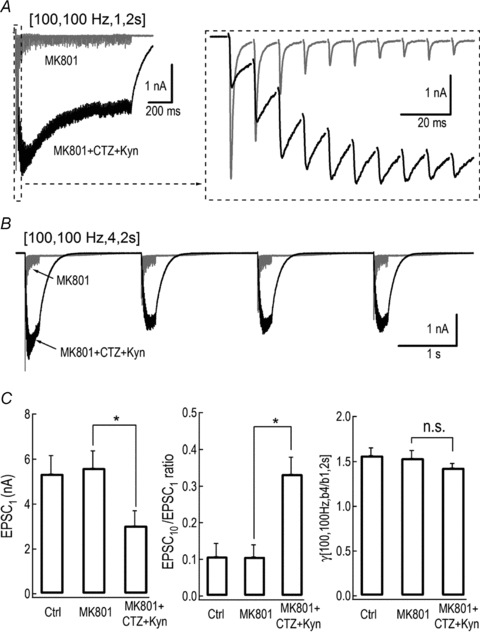

The burst-effect is mainly of presynaptic origin

During a long stimulation, EPSC amplitude/dynamics may be affected by postsynaptic AMPA receptor (AMPAR) desensitization and saturation (Neher & Sakaba, 2001a). At f > 10 Hz, kynurenate (Kyn) inhibits saturation while cyclothiazide (CTZ) blocks desensitization of AMPARs (Scheuss et al. 2002). To test whether modulation of postsynaptic AMPARs affects the extent of the burst-effect, CTZ (0.1 mm) and Kyn (1 or 2 mm) were added to the bath (Fig. 2A and B) after NMDA receptors were fully blocked by MK801 (10 μm). In the presence of these blockers, the amplitude of EPSCs was reduced from 5.4 ± 0.8 nA to 3.0 ± 0.7 nA (n = 6, P < 0.05, paired t test, Fig. 2C) while the depression level was apparently alleviated (0.33 ± 0.05) compared to that in the control solution (0.11 ± 0.04) (n = 5, P < 0.05, paired t test, Fig. 2C). When probed with the codes [100, 100 Hz, b, 2 s], no change in the burst-effect with (γ[b4/b1]= 1.57 ± 0.09, n = 5) or without CTZ and Kyn (γ[b4/b1]= 1.43 ± 0.05, n = 6) (P = 0.32, unpaired t test, Fig. 2C) was observed. In contrast, neither the amplitude of EPSCs, the extent of short-term depression nor the burst-effect was significantly altered by MK801 alone, suggesting that activity of residual NMDARs in the presence of extracellular Mg2+ at –60 mV plays no role in any of the parameters measured (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrated that robust postsynaptic AMPAR desensitization and saturation occur as evidenced by attenuated synaptic depression in CTZ and Kyn, but contribute little, if any, to the burst-effect.

Figure 2. Burst-effect was unaffected by AMPA receptor desensitization and saturation blockers.

A and B, representative traces of EPSCs produced by AP patterns [100, 100 Hz, b, 2 s] with [b = 1] (A) and [b = 4] (B) in the presence of MK801 (10 μm) alone (grey traces) or combined with CTZ (0.1 mm) and Kyn (1 or 2 mm) (black trace). Inset is the expanded first ten EPSCs. C, average amplitude of the first EPSCs (left), depression level (EPSC10/EPSC1) (middle) and γ[b4/b1] (right) with or without MK801 or combination of inhibitors are summarized.

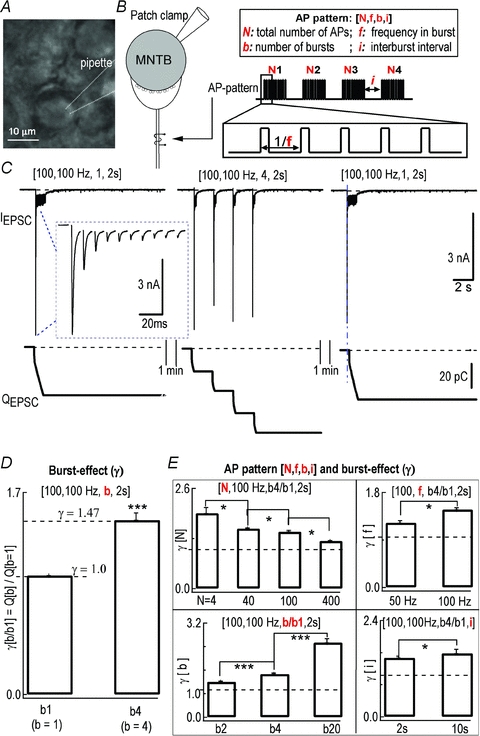

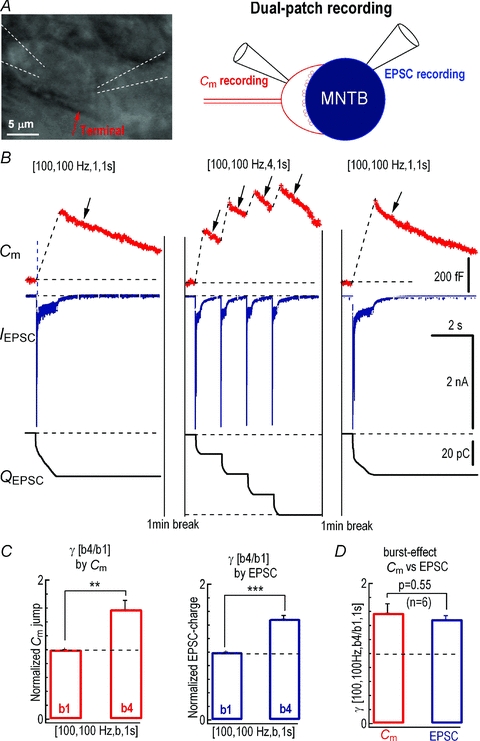

To directly probe the origin of the burst-effect, we made simultaneous paired recordings of presynaptic Cm and postsynaptic EPSCs from the calyx of Held synapse (Fig. 3A). The evoked release signals of Cm and QEPSC following the single burst pattern [100, 100 Hz, 1, 1 s] were 451 ± 49 fF (n = 6) and 82 ± 11 pC (n = 6), while those following [100, 100 Hz, 4, 1 s] were 713 ± 105 fF (n = 6) and 122 ± 8 pC (n = 6), respectively (Fig. 3B). Statistics showed that the burst-effect γ[100, 100 Hz, b4/b1, 1 s] as determined by either Cm (1.58 ± 0.13) or EPSC (1.49 ± 0.05) was similar (P = 0.55, n = 6, paired t test) (Fig. 3C and D). Together, these experiments (Figs 1–3) firmly established that the burst-effect was generated mainly from presynaptic terminals and was reliably transferred to postsynaptic neurons under our experimental conditions.

Figure 3. Both presynaptic Cm and EPSC recordings unravelled burst-effect.

A, image of a typical calyx of Held synapse and diagram of dual patch recordings which are carried out simultaneously with presynaptic Cm and postsynaptic EPSC recordings. B, representative recordings of Cm (top panels) and EPSCs (middle panels), and integration of total EPSC charge (bottom panels) evoked by axonal stimulation delivered with various AP patterns. Arrows indicate endocytosis following exocytosis. C, statistics of γ[b4/b1, i = 1 s] estimated from Cm and QEPSC are compared between stimulation patterns [100, 100 Hz, 1, 2 s] and [100, 100 Hz, 4, 2 s].

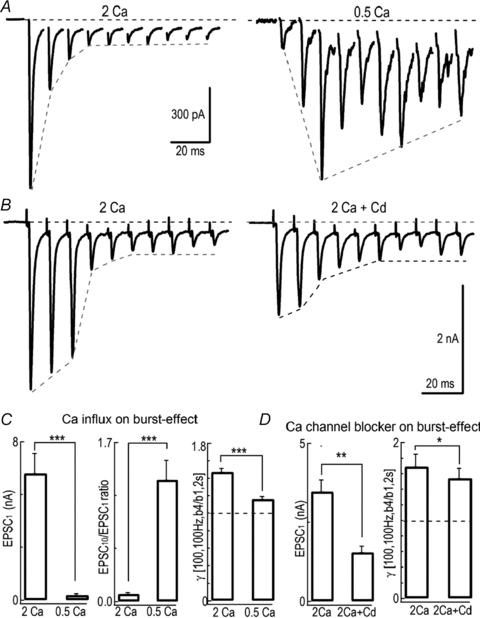

The impact of Ca2+ on the presynaptic burst-effect

We next attempted to determine the mechanisms underlying the burst-effect at the presynaptic terminals. There are several key factors in regulating exocytosis during prolonged stimulation, including SV release probability, the size of releasable vesicle pool and rate of replenishment. First, we assessed the effect of release probability on the burst-effect. Extracellular Ca2+ strongly affects release probability at the calyx of Held (Schneggenburger et al. 1999). Reducing extracellular [Ca2+] from 2 mm to 0.5 mm greatly decreased the amplitude of EPSCs from 5.7 ± 0.6 nA (n = 13) to 0.25 ± 0.08 nA (n = 10) (P < 0.001, unpaired t test) and dramatically lessened the depression level (2 mm Ca2+: 0.15 ± 0.03, n = 7 vs. 0.5 mm Ca2+: 1.30 ± 0.21, n = 8) (P < 0.001, unpaired t test, Fig. 4A and C). In 0.5 mm Ca2+ bath, the burst-effect was substantially attenuated under the AP patterns [100, 100 Hz, b, 2 s] with γ[b4/b1]= 1.16 ± 0.03 (n = 6) as compared to that in 2 mm Ca2+ bath (P < 0.001, unpaired t test, Fig. 4C). To block Ca2+ inflow through VGCCs, we controlled the amplitude of single EPSCs by positioning a puffer pipette containing Cd2+ (0.1 mm) close to the recorded cells. Application of Cd2+ significantly reduced the amplitude of initial EPSCs to 44 ± 3% (n = 5) of that obtained in the control solution ([Ca2+]o= 2 mm) (Control: 3.47 ± 0.37 nA versus Cd2+: 1.54 ± 0.20 nA, P < 0.01, paired t test, Fig. 4B and D) and decreased the burst-effect from γ[b4/b1]= 1.69 ± 0.16 to 1.54 ± 0.13 (P < 0.05, n = 5, paired t test, Fig. 4D). These results demonstrated that restricting Ca2+ entry into nerve terminals reduced release probability, slowed down depletion of SVs during repetitive activities and consequently attenuated the burst-effect, suggesting that Ca2+ plays an important role in mediating the burst-effect at this synapse.

Figure 4. Reducing Ca2+ inflow into the nerve terminal attenuated burst-effect.

A, example traces in response to stimulation trains at 100 Hz in 2 mm (left) and 0.5 mm[Ca2+]o (right). B, EPSCs evoked by a train of stimuli (100 Hz) in the absence (left) or presence of Cd2+ (0.1 mm) (right) while the [Ca2+]o is set at 2 mm. C, comparison of the amplitude of EPSCs, depression level and γ[b4/b1, i = 2 s] between 2 mm and 0.5 mm[Ca2+]o with stimulation [100, 100 Hz]. D, summary plots showing the effect of Cd2+ on the amplitude of first EPSCs and γ[b4/b1, i = 2 s].

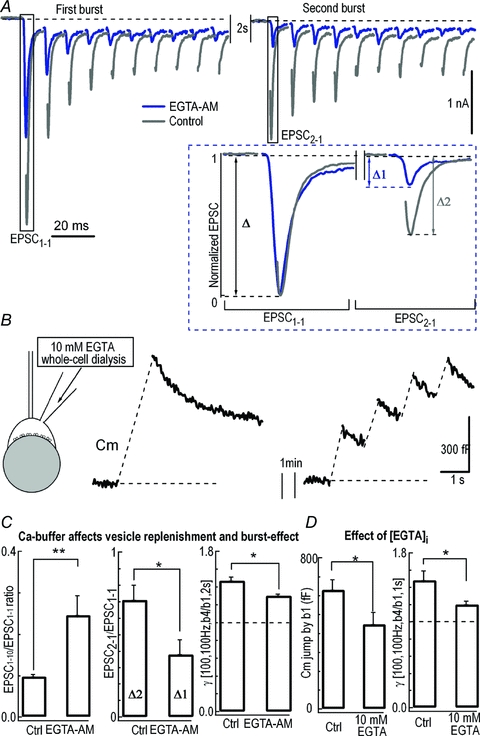

High-frequency stimulation is known to accelerate replenishment of SVs due to residual Ca2+ accumulation (von Ruden & Neher, 1993; Wang & Kaczmarek, 1998). Because Ca2+ spatiotemporal profiles may be different in various AP patterns, we next investigated whether the burst-effect is dependent on residual Ca2+ build-up in the calycal terminals (Fig. 5). After incubating slices with 50 μm EGTA-acetoxymethyl ester (EGTA-AM) for 30 min to buffer residual [Ca2+]i, less depression was observed (EPSC10/EPSC1 increased from 0.09 ± 0.03 (n = 7) to 0.25 ± 0.05 (n = 5), P < 0.01, unpaired t test, Fig. 5C). We further tested recovery from depletion of the releasable pool by calculating the ratio of the first EPSCs in two consecutive bursts (EPSC2-1/EPSC1-1) separated by 2 s. We observed a considerable drop in the recovery level from 0.78 ± 0.09 (n = 7, in control) to 0.38 ± 0.09 (n = 5 in EGTA-AM) (P < 0.05, unpaired t test, Fig. 5A inset and Fig. 5C; see also Wang & Kaczmarek, 1998; Sakaba & Neher, 2001a), accompanied by a significant decline of the burst-effect from γ[b4/b1] of 1.47 ± 0.04 (n = 7, in control) to 1.30 ± 0.02 (n = 5, in EGTA-AM) (P < 0.05, unpaired t test, Fig. 5C) with the stimulation patterns [100, 100 Hz, b4/b1, 2 s]. This indicated that Ca2+-dependent replenishment of the vesicle pool positively contributed to the burst-effect. To specifically examine the presynaptic effect of ambient Ca2+, we directly injected 10 mm EGTA into the presynaptic terminal through a patch pipette (Fig. 5B). In the presence of 10 mm EGTA, Cm jumps of 448 ± 64 fF (n = 4) and 540 ± 79 fF (n = 4) were induced by patterns [100, 100 Hz, b, 1 s] at b = 1 and b = 4, respectively. The burst-effect decreased from 1.48 ± 0.11 (n = 7) to 1.20 ± 0.04 (n = 4) due to this slow Ca2+ buffer (P < 0.05, unpaired t test, Fig. 5D). Moreover, there was a significant reduction in Cm jumps with the single burst stimulation between control (630 ± 54 fF, n = 7) and 10 mm EGTA dialysis (448 ± 64 fF, n = 4) (P < 0.05, unpaired t test, Fig. 5B and D), indicating that residual [Ca2+]i affects both replenishment and burst-facilitated exocytosis. These experiments suggested that presynaptic Ca2+ accumulation boosted the burst-effect during interburst intervals, which was further supported by a larger burst-effect under higher frequency stimulation (50 Hz vs. 100 Hz, Fig. 1E).

Figure 5. Residual Ca2+-modulated burst-effect.

A, example traces showing the first 10 EPSCs in the first two bursts under the stimulation pattern [100, 100 Hz, b4, 2 s] without (Control) or with 50 μm EGTA-AM pretreatment. EPSC1-1 and EPSC2-1 represent the first EPSCs in the first and second burst, respectively. The inset displays the expanded and normalized EPSC1-1 (Δ) and EPSC2-1 (Δ1 for EGTA-AM; Δ2 for Control). B, Cm was recorded with a whole-cell patch pipette containing 10 mm EGTA under patterns [100, 100 Hz, b4 or b1, 2 s]. C, comparison of the EPSC1-10/EPSC1-1 ratio in the first burst, recovery level (EPSC2-1)/ EPSC1-1, and γ[b4/b1, i = 2 s] under stimulation pattern [100, 100 Hz] in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of EGTA-AM as shown in A. D, summary plots of the amplitude of Cm jump (left panel) in response to [100, 100 Hz, b4/b1, 2 s] stimulation and γ[b4/b1, i = 2 s] (right panel) with or without presynaptic loading of 10 mm EGTA.

Conceptual model of the burst-effect

Because Ca2+ plays multifaceted roles in regulating release probability and depletion of SVs during repetitive synaptic activity, it is difficult to precisely delineate intricate interplays among multiple Ca2+-dependent processes (Forsythe et al. 1998). To determine the relative contribution of individual factors to the burst-effect, we performed computational simulations of the presynaptic burst-effect measured by Cm signals (Fig. 3B). For simplification, Ca2+-dependent exocytosis was calculated without considering endocytosis, because exocytosis-coupled-endocytosis following patterns [100, 100 Hz, b4, 1 s] and [100, 100 Hz, b1, 1 s] during the AP-bursts is similar (arrows in Fig. 3B). The [Ca2+]i profile during an action potential (recorded under current-clamp with fibre stimulation) (Helmchen et al. 1997; Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005) was simulated using a Hodgkin–Huxley (HH)-type m2 model (Borst & Sakmann, 1998; Wang et al. 2008) and converted with a peak of 27 μm and a half-width of 350 μs (inset in Fig. 6A, see Methods). Although we did not distinguish vesicle pools in the above experiments (Figs 1–5), the vesicle pools are composed of fast releasable vesicle pool (fRP) and slow releasable pool (sRP) (Sakaba & Neher, 2001b; Wang et al. 2008) with equal pool size (Sf=Ss) but different release probability (fRP is 10 times faster than sRP) (Neher, 2006), and both are replenished from an infinite pool with their own time constants (τf for fRP and τs for sRP). Each vesicle in either pool undergoes Ca2+-dependent release with a five-site kinetic model in response to AP-induced [Ca2+]i transients (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Wang et al. 2008).

With custom-made software (see Methods), a best fit of the experimental Cm recordings was achieved for a pool size of Sf=Ss= 1538 vesicles, and time constants for replenishment of τf= 8 s and τs= 0.5 s (Fig. 6A; for other parameters see Table 2), consistent with previous experimental results (Sakaba & Neher, 2001a; Sakaba, 2006; Wang et al. 2008). The presynaptic exocytosis induced by single-long-bursts and 4-short-bursts were 396 fF (124 fF (fRP) + 292 fF (sRP)) and 731 fF (191 fF (fRP) + 540 fF (sRP)). This burst-effect obtained from experimental recordings was well fitted by the simulation curves, except the decay phases, where endocytosis occurred in the experimental traces leading to the small mismatches (Fig. 6A). According to the simulation model and calculation of the contributions from fRP and sRP to the burst-effect, fRP and sRP were predicted to contribute 21.3% and 78.7% of the total burst-effect with AP patterns [100 APs, 100 Hz, b4/b1, 1 s]. We should emphasize that this estimation of fRP contribution probably represented an underestimation because the simulation (Fig. 6A, eqn (1) in Methods) did not include the contribution of residual Ca2+ potentiation of fRP replenishment (Fig. 5C, Wang & Kaczmarek, 1998; Sakaba & Neher, 2001a).

Using the above simulation, we examined several mechanistic aspects of the burst-effect at the synapse. First, local [Ca2+]i is determined by Ca2+ influx, Ca2+ clearance, and spatial coupling distance between Ca2+ channels and release vesicles. Varying the peak [Ca2+]i at the release site to mimic Ca2+ influx (assuming 27 μm corresponds to 2 mm[Ca2+]o, Fig. 6B, arrow), the burst-effect increased rapidly following [Ca2+]i increment from 6.75 μm to 27 μm. This prediction is in good agreement with our experiments of Fig. 4, where the AP-induced [Ca2+]i transients in 0.5 mm Ca2+ and 2 mm bath solutions corresponded to the burst-effect of γ[b4/b1] of 1.16 ± 0.03 and 1.47 ± 0.04. Second, effects of the vesicle pool size on the burst-effect were examined. The fRP/sRP ratio was negatively correlated to the burst-effect, while increasing the total pool size comprising equal fRP and sRP had little effect on the burst-effect (Fig. 6C). Third, the time constant of fRP replenishment (τf) was negatively correlated to the burst-effect at fixed τs#= 0.5 s, while that of sRP (τs) was bell-shaped correlated to the burst-effect at fixed τf#= 8 s (Fig. 6D). Although we did not include the Ca2+-dependent fRP replenishment in the simulations, the effect of residual [Ca2+]i on fSR replenishment and γ could be estimated by changing τf (Fig. 6D and Fig. 5; Sakaba & Neher, 2001a). Finally, according to the free diffusion theory at nano/microdomains (Chow & von Rudon, 1995), the relation of [Ca2+]i is proportional to Ca2+ flux through a Ca2+ channel,

| (3) |

where [Ca2+]ir indicates the local [Ca2+]i at the release site, δ is the distance between the Ca2+ channel and release site and δc is the δ value for the P8–P10 calyx (δc= 61 nm, Wang et al. 2009). By applying eqn (3) to Fig. 6B, the relation between the burst-effect (γ) and δ/δc was established (Fig. 6E). Following an AP, Fig. 6E predicted that: (1) the burst-effect was saturated/ maximized with the native [Ca2+]i (peak at 27 μm) (Fig. 6B); and (2) increasing the coupling distance from 1 δc to 1.6 δc reduced the burst-effect by 50% (Fig. 6E). Collectively, our simulations recapitulated experimental observations well and demonstrated that the burst-effect was primarily a confounding product of Ca2+-dependent depletion and replenishment of SVs.

Discussion

Our study has illustrated that AP patterns dramatically modulate short term plasticity via not only primary AP codes [N, f] but also the burst codes [b, i] at a central synapse. Comparison of the exocytotic output produced by two AP patterns with the same primary codes [N, f] but different burst codes [b, i] has revealed that multiple short AP bursts significantly elevate neurotransmitter release largely resulting from presynaptic accumulation of Ca2+ during repetitive neural activities, independent of postsynaptic receptor desensitization or saturation. Computer simulations suggest that the burst-effect is probably controlled by an intricate balance between Ca2+-dependent depletion and replenishment of SVs at this synapse.

On the one hand, the releasable pools (fRP and sRP) of SVs are quickly depleted by the first 2–5 APs during an AP burst (Fig. 1C), leading to short-term depression. On the other hand, burst patterns produce residual [Ca2+]i and synaptic facilitation because multi-short-burst pattern [b = 4, i = 2 s] accelerates Ca2+-dependent replenishment at the interburst intervals (Fig. 5). Consequently, more vesicles would be readily released (Fig. 1C and E). This probably accounts for the facilitation effect of the pattern [b = 4]versus[b = 1]. However, it opens another important question: with given AP number (N) and total recording time (T), what pattern produces maximum release per AP in the central synapse? According to experimental results in Fig. 1E, the maximum γ occurs at [N, f=N/T, b=N, i = 0]. This is the pattern of maximum b (b=N) or minimum b = 1 at lowest f. Thus, the efficacy ranking order of AP patterns for quantal output is: single AP burst at the average frequency (f1=N/T) > multiple AP bursts at the high frequency (b≥ 2, f2 > N/T) > single AP burst at the high frequency (f2 > N/T). This finding may have physiological implications for understanding the differences in AP pattern-dependent release profiles from synapses and somatic neurons or endocrine cells such as chromaffin cells and cells in the locus coeruleus (Duan et al. 2003; Huang et al. 2007).

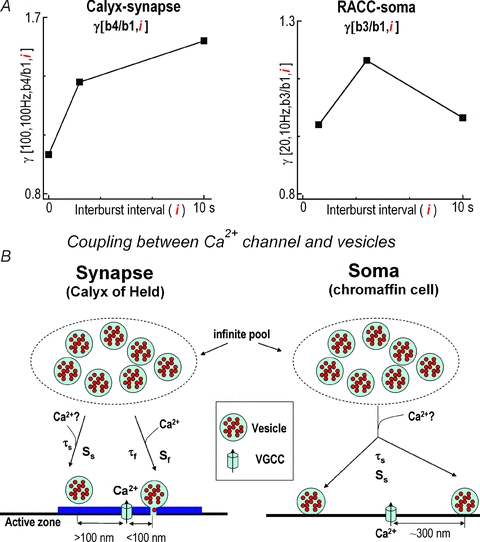

During an AP burst in adrenal chromaffin cells, the burst-effect of exocytosis is regulated by two opposing factors: ‘Ca2+ accumulation’ and ‘vesicle depletion’. A single AP cannot effectively trigger release but repetitive APs lead to Ca2+ accumulations which facilitate the Ca2+-dependent transmitter release during a small number of bursts. In this case, vesicle depletion from the small pool inhibits sustained neurotransmission (Zhou & Misler, 1995) but this depletion could be prevented by the large pool of vesicles. Therefore, the burst-effect of γ in chromaffin cells is determined by a combination of accumulated [Ca2+]i/facilitation of release and vesicle depletion (Duan et al. 2003). In contrast, γ in the calyx of Held synapses is dominantly determined by vesicle depletion/replenishment because even a single AP is sufficient to trigger release of a large number of available vesicles (Fig. 1). Thus, the burst-effect at synapses versus somatic chromaffin cells must be mediated by fundamentally different mechanisms.

We have built a conceptual model as illustrated in Fig. 7B which intends to define the mechanisms separating the two types of exocytosis: (1) the somatic/slow/loose-coupling type (Zhou & Misler, 1995; Meinrenken et al. 2002; Wu et al. 2009); and (2) the synaptic/fast/tight-coupling type (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Meinrenken et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2008). Generally, both fast and slow exocytosis are found in synapses as well as in somata, but the fraction of fast exocytosis is much larger at the calyx of Held synapse (∼70%, Sakaba, 2006; Sun et al. 2007) vs. rat chromaffin cell body (∼10%, (Zhou & Misler, 1995). Those fast and slow exocytosis systems will thus be differentially elicited by various firing patterns, allowing the mixture of fast and slow exocytosis to fulfil different and/or complementary functions at a synapse/soma (for example, fast and slow exocytosis are 50:50 in calf chromaffin cells (Elhamdani et al. 1998).

Figure 7. Distinct models of exocytosis at the calyx of Held synapse and rat adrenal chromaffin cells (RACCs).

A, plots of γ[b4/b1] under stimulation pattern [100, 100 Hz, b4, i = 2 or i = 10 s] in the calyx of Held as illustrated in Fig. 1E and normalized γ(b3/b1) under stimulation patterns [20, 10 Hz, b3, i = 1, 4 and 10 s] in RACCs in our previous report (Duan et al. 2003). B, both calyx of Held and RACCs secrete vesicles in a Ca2+-dependent fashion. The distance between Ca2+ channels and release sites at the calyx of Held (about 100 nm) is much closer than at RACCs (about 300 nm) (Zhou & Misler, 1995; Elhamdani et al. 1998; Meinrenken et al. 2002; Wu et al. 2009). The vesicular pools in the calyx of Held include both the fRP (Sf for its size) and sRP (Ss for its size) while RACCs only have the sRP. Both the fRP and sRP recruit vesicles from an infinite pool with the time constant τf for fRP and τs for sRP. τf depends on residual Ca2+, which can be accelerated by high frequency firing or prolonged depolarization. Question marks ‘?’ indicate speculative steps lacking direct evidence.

Our simulation of the burst-effect provides several physiologically relevant predictions, which are currently not measurable. For example, the burst-effect is sensitive to the following alterations of parameters from the standard physiological conditions (release site [Ca2+]i= 27 μm, fRP = sRP = 1538; τf= 8 s; τs= 0.5 s): (1) reducing Ca2+ influx greatly attenuates the burst-effect, which may be caused by inactivation of G protein-coupled receptors or VGCCs (Takahashi et al. 1996; Forsythe et al. 1998) while augmentation of Ca2+ influx has little effect (Fig. 6B); (2) increasing the coupling distance between release sites and Ca2+ channels by 60% attenuates the burst-effect by 50% while reducing the coupling distance has little effect; (3) decreasing the size of the fRP enhances the burst-effect, while change in the sRP has the opposite effect (Fig. 6C); (4) finally, accelerating replenishment rate of the fRP by tenfold (from τf= 8 s to τf= 0.8 s, when τs is fixed at 0.5 s), which may occur upon physiological stimulation (Hosoi et al. 2007), boosts the burst-effect from 1.69 to 1.88, while slowing the replenishment rate by tenfold (from τf= 8 s to τf= 80 s, when τs is fixed at 0.5 s) attenuates the burst-effect from 1.69 to 1.64 (Fig. 6D). The rate of fRP replenishment depends on residual [Ca2+]i at the calyx of Held nerve terminal (Wang & Kaczmarek, 1998; Sakaba & Neher, 2001a). High-frequency AP bursts (100 Hz) (Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2003; Lorteije et al. 2009) increase residual [Ca2+]i, which thereby promotes vesicle replenishment (∼tenfold) (Hosoi et al. 2007) and consequently increase the burst-effect (Fig. 1E). Vesicle recruitment also significantly accelerates when temperature is set at a more physiological level (Kushmerick et al. 2006). However, in this case, the replenishment rate for both fRP and sRP could be increased simultaneously, resulting in a decrease in the burst-effect (Fig. 6D). Although the above predictions provide interesting insights about the burst-effect, one should note that our simulation is an approximation at best because the following factors are not included in this model: (1) exocytosis-coupled endocytosis (Fig. 6A); (2) the effect of residual Ca2+ on exocytosis (Fig. 5D); (3) Ca2+ dependence of replenishment (τf); and (4) Ca2+ channel inactivation during repeated AP stimulation (Forsythe et al. 1998; Xu & Wu, 2005).

The similar burst-effect observed with presynaptic release (Cm) and postsynaptic responses (EPSCs) (Fig. 3) confirmed the presynaptic origin of the burst-effect. Both the release probability per active zone (0.09–0.91) and the released fraction of the RRP (∼5%) during an AP in slice (Schneggenburger et al. 2002; Wu & Wu, 2009) and in vivo (Lorteije et al. 2009) were similar to other conventional boutons (Zucker & Regehr, 2002). Therefore, our results may have general implications for other central synapses, in which firing patterns are contextually dependent on distinct inputs patterns (Kandel & Spencer, 1961; Ranck, 1973; Connors & Gutnick, 1990; Vincent & Marty, 1996; Lu & Trussell, 2000; Ramcharan et al. 2000; Hefft & Jonas, 2005; Lorteije et al. 2009). For assessment of quantal output, EPSCs are assumed to be a reliable measurement of release at the calyx of Held synapse (Sun & Wu, 2001) only in the presence of CTZ and Kyn during repeated stimulation (Turecek & Trussell, 2000; Taschenberger et al. 2002). Assuming a single vesicle has a Cm of 0.065 fF and induced charge of 0.03 pC (in the absence of CTZ, miniature EPSC (mEPSC) had an amplitude of 30 pA and decayed monoexponentially with a time constant of 1 ms (Neher & Sakaba, 2001a), then the number of vesicles released by a long train of APs ([100, 100 Hz, b1, 1 s]) according to Cm and mEPSCs in Fig. 3 are ∼6900 vesicles (451 fF/0.065 fF) and ∼2700 vesicles (82 pC/0.03 pC), respectively. This difference in the estimates of released vesicles with Cm and EPSCs may be due to ectopic release being only reflected by Cm but not by EPSCs, and/or an underestimation of the total quantal output because of postsynaptic AMPAR desensitization and saturation during a prolonged stimulation (mEPSC is reduced from 30 pA to 10 pA) (Neher & Sakaba, 2001a,b; Wong et al. 2003; Renden et al. 2005; Hermann et al. 2007). However, to our surprise, CTZ and Kyn had very little effect on γ[b4/b1], although they substantially decreased the amplitude and decay rate of single EPSCs and the extent of short-term depression during a train of EPSCs (Fig. 2). Thus, the burst-effect at the calyx of Held synapse may represent a new form of short term plasticity with a presynaptic locus of origin, in addition to the classic short-term potentiation and short-term depression at central synapses (Zucker & Regehr, 2002).

In conclusion, our systematical investigation demonstrated that the presynaptic burst-effect of AP-induced synaptic transmission was a product of two opposing mechanisms: depression by vesicle depletion during a burst and facilitation by vesicle replenishment, which is partially [Ca2+]i dependent. We suggest that differences in the coupling modalities between VGCCs and vesicles and dynamics of vesicle pools in response to AP bursts may account for distinct burst-effects on synaptic and somatic release (Fig. 7).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Iain C. Bruce for critical comments. This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2006CB500800; 2007CB512100) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (30728009, 30770521, 30770788, 30970660, 30911120491 and 30830043), and a China-Canada Joint Health Research Initiative grant from NSFC and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. L.-Y.W. holds a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Brain and Behavior.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMPAR

AMPA receptor

- AP

action potential

- CTZ

cyclothiazide

- fRP

fast releasable pool

- HH

Hodgkin–Huxley

- Kyn

kynurenate

- MNTB

medial nuclei of the trapezoid body

- PT

physiological temperature

- RACCs

rat adrenal chromaffin cells

- RT

room temperature

- sRP

slow releasable pool

- SV

synaptic vesicle

- VGCC

voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

Author contributions

The experiments were performed at the Institute of Molecular Medicine, Peking University by B.Z., Y.-M.Y., H.-P.H., F.-P.Z., L.W., X.-Y.Z., S.G. and P.-L.Z. The simulations were carried out by B.Z., L.S., Z.Z. and J.-P.D. The study was designed by Z.Z., B.Z., L.-Y.W. and C.X.Z. The paper was written by Z.Z., B.Z. and L.-Y.W. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Borst JG, Helmchen F, Sakmann B. Pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body of the rat. J Physiol. 1995;489:825–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium current during a single action potential in a large presynaptic terminal of the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;506:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.143bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezina V, Church PJ, Weiss KR. Temporal pattern dependence of neuronal peptide transmitter release: models and experiments. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6760–6772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06760.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RH, von Rudon L. Electrochemistry detection of secretion from single cells. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single Channel Recording. 2nd edn. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 245–275. [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Gutnick MJ. Intrinsic firing patterns of diverse neocortical neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90185-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan K, Yu X, Zhang C, Zhou Z. Control of secretion by temporal patterns of action potentials in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11235–11243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11235.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhamdani A, Zhou Z, Artalejo CR. Timing of dense-core vesicle exocytosis depends on the facilitation L-type Ca channel in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6230–6240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06230.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn MJ, Wang LY. Developmental transformation of the release modality at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4131–4140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID. Direct patch recording from identified presynaptic terminals mediating glutamatergic EPSCs in the rat CNS, in vitro. J Physiol. 1994;479:381–387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Cuttle MF, Takahashi T. Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron. 1998;20:797–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefft S, Jonas P. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1319–1328. doi: 10.1038/nn1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium dynamics associated with a single action potential in a CNS presynaptic terminal. Biophys J. 1997;72:1458–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann J, Pecka M, von Gersdorff H, Grothe B, Klug A. Synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held under in vivo-like activity levels. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:807–820. doi: 10.1152/jn.00355.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi N, Sakaba T, Neher E. Quantitative analysis of calcium-dependent vesicle recruitment and its functional role at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14286–14298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4122-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HP, Wang SR, Yao W, Zhang C, Zhou Y, Chen XW, Zhang B, Xiong W, Wang LY, Zheng LH, Landry M, Hokfelt T, Xu ZQ, Zhou Z. Long latency of evoked quantal transmitter release from somata of locus coeruleus neurons in rat pontine slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1401–1406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608897104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Spencer WA. Electrophysiology of hippocampal neurons. II. After-potentials and repetitive firing. J Neurophysiol. 1961;24:243–259. doi: 10.1152/jn.1961.24.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Fuchs K, Lippe WR, Tempel BL, Rubsamen R. Decreased temporal precision of auditory signaling in Kcna1-null mice: an electrophysiological study in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9199–9207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09199.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick C, Renden R, von Gersdorff H. Physiological temperatures reduce the rate of vesicle pool depletion and short-term depression via an acceleration of vesicle recruitment. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1366–1377. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum ME, Zhu JJ, Sakmann B. A new cellular mechanism for coupling inputs arriving at different cortical layers. Nature. 1999;398:338–341. doi: 10.1038/18686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever IJ, Bradbury EJ, Cunningham JR, Adelson DW, Jones MG, McMahon SB, Marvizon JC, Malcangio M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is released in the dorsal horn by distinctive patterns of afferent fiber stimulation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4469–4477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04469.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau M, Neher E. Patch-clamp techniques for time-resolved capacitance measurements in single cells. Pflugers Arch. 1988;411:137–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00582306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE. Bursts as a unit of neural information: making unreliable synapses reliable. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:38–43. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorteije JA, Rusu SI, Kushmerick C, Borst JG. Reliability and precision of the mouse calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13770–13784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3285-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Trussell LO. Inhibitory transmission mediated by asynchronous transmitter release. Neuron. 2000;26:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinrenken CJ, Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium secretion coupling at calyx of Held governed by nonuniform channel–vesicle topography. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1648–1667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01648.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. A comparison between exocytic control mechanisms in adrenal chromaffin cells and a glutamatergic synapse. Pflugers Arch. 2006;453:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakaba T. Combining deconvolution and noise analysis for the estimation of transmitter release rates at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2001a;21:444–461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakaba T. Estimating transmitter release rates from postsynaptic current fluctuations. J Neurosci. 2001b;21:9638–9654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09638.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramcharan EJ, Gnadt JW, Sherman SM. Burst and tonic firing in thalamic cells of unanesthetized, behaving monkeys. Visual Neurosci. 2000;17:55–62. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800171056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranck JB., Jr Studies on single neurons in dorsal hippocampal formation and septum in unrestrained rats. I. Behavioral correlates and firing repertoires. Exp Neurol. 1973;41:461–531. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(73)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renden R, Taschenberger H, Puente N, Rusakov DA, Duvoisin R, Wang LY, Lehre KP, von Gersdorff H. Glutamate transporter studies reveal the pruning of metabotropic glutamate receptors and absence of AMPA receptor desensitization at mature calyx of Held synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8482–8497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1848-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T. Roles of the fast-releasing and the slowly releasing vesicles in synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5863–5871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0182-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Calmodulin mediates rapid recruitment of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2001a;32:1119–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Quantitative relationship between transmitter release and calcium current at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2001b;21:462–476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuss V, Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Separation of presynaptic and postsynaptic contributions to depression by covariance analysis of successive EPSCs at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2002;22:728–739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00728.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Meyer AC, Neher E. Released fraction and total size of a pool of immediately available transmitter quanta at a calyx synapse. Neuron. 1999;23:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406:889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Sakaba T, Neher E. Vesicle pools and short-term synaptic depression: lessons from a large synapse. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM. Tonic and burst firing: dual modes of thalamocortical relay. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:122–126. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag M, Englitz B, Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Rubsamen R. Early postnatal development of spontaneous and acoustically evoked discharge activity of principal cells of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: an in vivo study in mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9510–9520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1377-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Pang ZP, Qin D, Fahim AT, Adachi R, Sudhof TC. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 2007;450:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nature06308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JY, Wu LG. Fast kinetics of exocytosis revealed by simultaneous measurements of presynaptic capacitance and postsynaptic currents at a central synapse. Neuron. 2001;30:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JY, Wu XS, Wu LG. Single and multiple vesicle fusion induce different rates of endocytosis at a central synapse. Nature. 2002;417:555–559. doi: 10.1038/417555a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Xiong Y, Zeng X, Wu Y, Pan N, Lingle CJ, Qu A, Ding J. Differential regulation of action potentials by inactivating and noninactivating BK channels in rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Biophys J. 2009;97:1832–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger H, Leao RM, Rowland KC, Spirou GA, von Gersdorff H. Optimizing synaptic architecture and efficiency for high-frequency transmission. Neuron. 2002;36:1127–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell LO. Synaptic mechanisms for coding timing in auditory neurons. Annual review of physiology. 1999;61:477–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecek R, Trussell LO. Control of synaptic depression by glutamate transporters. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2054–2063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-02054.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent P, Marty A. Fluctuations of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in Purkinje cells from rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol. 1996;494:183–199. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Borst JG. Short-term plasticity at the calyx of Held. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:53–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Schneggenburger R, Weis S, Neher E. Presynaptic depression at a calyx synapse: the small contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8137–8146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ruden L, Neher E. A Ca-dependent early step in the release of catecholamines from adrenal chromaffin cells. Science. 1993;262:1061–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.8235626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Fedchyshyn MJ, Yang YM. Action potential evoked transmitter release in central synapses: insights from the developing calyx of Held. Mol Brain. 2009;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Kaczmarek LK. High-frequency firing helps replenish the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1998;394:384–388. doi: 10.1038/28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Neher E, Taschenberger H. Synaptic vesicles in mature calyx of Held synapses sense higher nanodomain calcium concentrations during action potential-evoked glutamate release. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14450–14458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4245-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AY, Graham BP, Billups B, Forsythe ID. Distinguishing between presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms of short-term depression during action potential trains. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4868–4877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04868.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Llobet A, Lagnado L. Loose coupling between calcium channels and sites of exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 2009;15:5377–5391. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XS, Wu LG. Rapid endocytosis does not recycle vesicles within the readily releasable pool. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11038–11042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2367-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wu LG. The decrease in the presynaptic calcium current is a major cause of short-term depression at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2005;46:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Wang LY. Amplitude and kinetics of action potential-evoked Ca2+ current and its efficacy in triggering transmitter release at the developing calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5698–5708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Misler S. Action potential-induced quantal secretion of catecholamines from rat adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3498–3505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]