Non-technical summary

Highly sensitive mechanoreceptors in the skin are responsible for our ability to discriminate fine textures. One feature of skin mechanoreceptors in mammals is their high sensitivity and speed. We show here that an ion channel that passes calcium ions following very small membrane depolarization caused by tactile stimuli acts as an amplifier increasing mechanoreceptor sensitivity. We also show that this calcium ion channel, called Cav3.2, only amplifies mechanosensory signals in a subset of touch receptors which happen to be several-fold more sensitive than other specialized mechanoreceptors. Thus, the expression of one specific calcium channel serves especially to increase the speed of tactile encoding. The special sensitivity and high speed of these touch receptors may enable animals and humans to react very rapidly to tactile stimuli that guide movement.

Abstract

Abstract

In mammals there are three types of low-voltage-activated (LVA) calcium channels, Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3, which all give rise to T-type Ca2+currents. T-type Ca2+currents have long been known to be highly enriched in a sub-population of medium-sized sensory neurones in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG). However, the identity of the T-type-rich sensory neurones has remained controversial and the precise physiological role of the Cav3.2 calcium channel in these sensory neurones has not been directly addressed. Here we show, using Cav3.2−/− mutant mice, that these channels are essential for the normal temporal coding of moving stimuli by specialized skin mechanoreceptors called D-hair receptors. We show that D-hair receptors from Cav3.2−/− fire approximately 50% fewer spikes in response to ramp-and-hold displacement stimuli compared to wild type receptors. The reduced sensitivity of D-hair receptors in Cav3.2−/− mice is chiefly due to an increase in the mechanical threshold and a substantial temporal delay in the onset of high-frequency firing to moving stimuli. We examined the receptive properties of other cutaneous mechanoreceptors and Aδ- and C-fibre nociceptors in Cav3.2−/− mice, but found no alteration in their mechanosensitivity compared to Cav3.2+/+ mice. However, C-fibre nociceptors recorded in Cav3.2−/− mutant mice displayed a small but statistically significant reduction in their spiking rate during noxious heat ramps when compared to C-fibres in control mice. The T-type calcium channel Cav3.2 is thus not only a highly specific marker of D-hair receptors but is also required to maintain their high sensitivity and above all to ensure ultra rapid temporal detection of skin movement.

Introduction

The sensations of touch, vibration and mechanical pain are mediated by activation of distinct primary afferent receptor types in the skin (Lewin & Moshourab, 2004). In the mouse, low-threshold mechanoreceptors have been classified into three major types: slowly adapting mechanoreceptors (SAMs), rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors (RAMs) and D-hair receptors (Koltzenburg et al. 1997; Martinez-Salgado et al. 2007; Wetzel et al. 2007; Milenkovic et al. 2008). The distinctive physiological properties of different mechanoreceptor types are presumably determined by the differential expression of genes, which might be specific markers of different mechanoreceptor types. Until recently, the only marker described for a mechanoreceptor population was mRNA expression for the T-type voltage-gated calcium channel Cav3.2 (Perez-Reyes, 2003), found almost exclusively in D-hair receptors (Shin et al. 2003). D-hair receptors are rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors with slowly conducting Aδ-fibre axons, have extremely low mechanical thresholds, and unlike other mechanoreceptors are particularly sensitive to slowly moving stimuli (Brown & Iggo, 1967; Dubreuil et al. 2004; Milenkovic et al. 2008; Lennertz et al. 2010). Recently, it was found that large sensory neurones expressing the mafA gene (v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A) and the tyrosine kinase receptor c-RET (ret proto oncogene) are probably identical to a population of RAMs innervating hair follicles or Meissner's corpuscles in the glabrous skin (Bourane et al. 2009; Luo et al. 2009). It was, however, not clear from these reports whether D-hair receptors are also defined by mafA/c-RET expression.

It has been known for some time that low-voltage-activated (T-type) voltage-gated calcium currents are present in sensory neurones (Carbone & Lux, 1984a,b; Schroeder et al. 1990). The Cav3.2 gene encodes one of the three low-voltage-activated (LVA) Ca2+ channels (Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3), and the mRNA for all three genes has been detected in the DRG using in situ hybridisation and real-time PCR (Talley et al. 1999; Shin et al. 2003). The LVA (T-type) channels are opened by weak depolarization and the activation of the current is mostly found to be transient (Perez-Reyes, 2003). It has been reported that LVA channels, in particular Cav3.2, may be involved in regulating the excitability of primary afferent nociceptors (Todorovic et al. 2001; Nelson et al. 2007a; Lee et al. 2009). However, our studies using mibefradil, a drug that blocks all T-type channels, suggested that only the mechanosensitivity of D-hair receptors is reduced by blockade of LVA channels (Shin et al. 2003). Since the available pharmacological tools cannot distinguish between the three LVA channels, we have now used Cav3.2 null mutant mice to directly address the role of this channel in sensory transduction in cutaneous mechanoreceptors and nociceptors. We show that D-hair receptors are drastically impaired in their ability to encode the temporal properties of moving stimuli. This mechanosensitivity deficit can be accounted for by Cav3.2 channels acting as an initial amplifier of the receptor potential specifically in D-hair receptors. The functional properties of other cutaneous mechanoreceptors and mechanosensitive nociceptors were largely unaffected by deletion of the Cav3.2 gene. Thus, the specific expression of Cav3.2 channels in D-hair receptors may enable fast temporal encoding of very small moving stimuli applied to the skin.

Methods

Animals

Cav3.2−/− mice were provided by C. C. Chen and K. P. Campbell from the University of Iowa Animal Care Unit and kept in the animal house of the MDC until they were used for experiments. Cav3.2−/− mice were generated by gene targeting in mouse ES cells. The targeting vector was designed to delete the IS5 region of murine Cacna1H gene, which resulted in deletion of exon 6, corresponding to amino acid residues 216 to 267 (Chen et al. 2003). Mice were genotyped for wild type and the targeted allele using a genomic PCR, Cav3.2 wild type allele: forward: 5′-ATTCAAGGGCTTCCACAGGGTA-3′, reverse: 5′-CATCTCAGGGCCTCTGGACCAC-3′; targeted allele forward: 5′-ATTCAAGGGCTTCCACAGGGTA-3′, reverse: 5′-GCTAAAGCGCATGCTCCAGACTG-3′.

The in vitro skin–nerve preparation

Animals were killed by exposure to a rising concentration of CO2 gas, a method approved by and in accordance with guidelines from the Berlin state authorities responsible for regulating animal experimentation. The hind limb skin was shaved and the area innervated by the saphenous nerve was removed with the nerve intact. To facilitate oxygenation of the tissue, the skin was placed corium-side up in an organ bath, where it was fixed with insect needles, and superfused with 32°C warm oxygen-saturated synthetic interstitial fluid (SIF) at a flow rate of 10 ml min−1. SIF buffer consists of (in mm): NaCl (123); KCl (3.5); MgSO4 (0.7); NaH2PO4 (1.7); CaCl2 (2.0); sodium gluconate (9.5); glucose (5.5); sucrose (7.5); Hepes (10) at a pH of 7.4. The saphenous nerve was pulled through a gap to the recording chamber and laid on top of a small mirror that served as the dissection plate. The aqueous solution in the recording chamber was overlaid by mineral oil such that the interface was located just below the surface of the mirror. Fine forceps (Dumont no. 5 F.S.T.) were used to desheath the nerve, carefully removing its surrounding epineurium, and to tease small filaments from the nerve so that the activity from single units could be recorded by placing the individual strands of the nerve onto the silver recording electrode installed in the wall of the chamber.

All data were collected and saved to disk using Chart 5 software for the Powerlab system running on a PC (ADInstruments). For each single unit the data were analysed off-line using the Spike histogram extension of Chart software. This software allows calculation of histograms of spikes discriminated on the basis of a constant height and width. The receptive fields of identified fibres were found by probing the skin with a glass rod. In this way up to 90% of thin myelinated or unmyelinated nociceptors and virtually all of the low-threshold mechanoreceptors can be activated (Kress et al. 1992; Wetzel et al. 2007). Once the borders of the receptive field were determined, a Teflon-coated silver electrode with a non-insulated tip (diameter <0.5 mm) was placed on the most sensitive spot of the receptive field, and square-wave pulses of constant current were used to initiate action potentials The stimulus intensity was set at approximately two-times the threshold with a pulse duration of 50–500 μs depending on the afferent under investigation. The latency between the stimulus artifact and the resulting AP was measured. To calculate the conduction velocity the distance between the stimulating and the recording electrode was divided by this latency. Units could thus be grouped into three classes: Aβ-fibres, which are thickly myelinated units, have a conduction velocity faster than 10 m s−1; Aδ-fibres are thinly myelinated units with a conduction velocity of 1–10 m s−1; and non-myelinated C-fibres conduct slower than 1 m s−1 (Milenkovic et al. 2008).

The mechanical threshold was established using calibrated von Frey hairs applied perpendicular to the receptive field. The weakest von Frey filament in this study exerted a bending force of 0.4 mN. von Frey hairs with even lower bending forces were not used as they did not easily penetrate the surface tension of the Ringer solution covering the skin. After electrical stimuli, by using a probe fixed to a linear stepping motor under computer control (Nanomotor Kleindiek Nanotechnik), a standard ascending series of displacement stimuli were applied to the receptive field at 30 s intervals and each displacement was maintained for 10 s. Each stimulus–response function started at threshold as the probe was adjusted so that the first 6 μm displacement evoked spikes. The delay between the start of the mechanical probe movement and the first spike, corrected for the electrical conduction delay of the tested fibre, was designated as the mechanical latency. For further characterizing of the rapidly adapting receptors, RAM and D-hair, an increasing velocity program was applied at 48 and 96 μm step stages. By changing the time course used to reach certain displacement, the stimulating velocities were varied from 6 μm s−1 to 3000 μm s−1 at 48 μm and 96 μm steps (Milenkovic et al. 2008). Nociceptors (AMs and nociceptive C-fibres) were subjected only to a series of increasing ramp-and-hold stimuli as these afferents have no significant sensitivity to moving stimuli (Milenkovic et al. 2008). A peltier element-based contact probe was used for applying ramp thermal stimuli to the receptive fields of single C-fibres as described previously (Milenkovic et al. 2007). The peltier device and control electronics is a custom device built by the Yale School of Medicine Instrumentation Repair and Design Shop.

Cell culture

For all experiments, overnight DRG cultures from adult C57BL/6N mice and Cav3.2−/− mice (6–12 weeks) were used. Mice were killed by placing the animals into a chamber filled with an increasing CO2 concentration. For each culture, DRGs from all spinal segments were dissected, collected in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free PBS and subsequently treated with collagenase IV (1 mg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich) and trypsin (0.05%, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 30 min, respectively. Digested DRGs were washed twice with growth medium (DMEM-F12; Invitrogen) supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mm, Sigma-Aldrich), glucose (8 mg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich), penicillin (200 U ml−1)–streptomycin (200 μg ml−1) (both Sigma) and 5% horse serum (PPA), triturated using fire-polished Pasteur pipettes and plated in a droplet of growth medium on a glass coverslip pre-coated with 100 μg ml−1 poly-l-lysine (20 μg cm−2, Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 μg ml−1 laminin (4 μg cm−2, Invitrogen). To allow neurones to adhere, coverslips were kept for 3–4 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% incubator before being flooded with fresh growth medium. Cultures were used for patch-clamp experiments on the next day.

Patch-clamp experiments

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made at room temperature (20–24°C) from cultures prepared as described above. Patch pipettes were pulled (Flaming-Brown puller, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) from borosilicate glass capillaries (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany), filled with a solution consisting of (mm): KCl (110), NaCl (10), MgCl2 (1), EGTA (1) and Hepes (10), adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH and had tip resistances of 6–8 MΩ. The bathing solution contained (mm): NaCl (140), KCl (4), CaCl2 (2), MgCl2 (1), glucose (4), Hepes (10), adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Drugs were applied with a gravity-driven multibarrel perfusion system (WAS-02). All recordings were made using an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) in combination with Patchmaster and Fitmaster software (HEKA). Pipette and membrane capacitance were compensated using the auto function of Patchmaster and series resistance was compensated by 50% to minimize voltage errors. APs were evoked by repetitive 80 ms current injections increasing from 200 or 500 pA to 2600 or 6500 pA with increments of 200 or 500 pA. Mechanically activated currents were recorded as previously described (Hu & Lewin, 2006; Lechner et al. 2009). Briefly, neurones were clamped to −60 mV, stimulated mechanically with a fire-polished glass pipette (tip diameter 2–3 μm) that was driven by a piezo-based Nanomotor micromanipulator (MM3A, Kleindiek Nanotechnik, Reutlingen, Germany) and the evoked whole-cell currents were recorded with a sampling frequency of 200 kHz. The stimulation probe was positioned at an angle of 45 deg to the surface of the dish and moved with a velocity of 4.3 μm ms−1. Mechanical stimuli were always applied to the neurites and the cell was always locally superfused with 1 μm TTX to avoid contamination by voltage-gated conductances (Hu & Lewin, 2006; Hu et al. 2010). Currents were fitted with single exponential functions and classified as RA-, IA- and SA-type currents according to their inactivation time constant (Hu & Lewin, 2006; Lechner et al. 2009).

Data and statistical analyses

All APs were counted in a time period of 10 s after the onset of a mechanical stimulus because this time window contained all spikes during the rise time, the plateau and the discharge during the release of the stimulus. Further quantitative analysis of the recorded APs was carried out by repeated-measures ANOVA tests with Graphpad Prism 4 software by Graphpad software Inc. In the case of repeated-measures ANOVA analyses, P values, when significant, are given for the total curve together with P values for individual points on the curve using a Bonferroni post hoc test, if significant. All values are presented as means ± SEM. A level of 5% was taken as evidence of statistical significance.

Results

We recorded 101 single units with myelinated A-fibres and 47 single units with unmyelinated C-fibres from C57BL/6N mice and 85 single units with myelinated A-fibres and 41 C-fibres from Cav3.2−/− mice on a C57BL/6N genetic background (Chen et al. 2003). The firing behaviour of single sensory afferents in response to mechanical stimuli was examined in the saphenous nerve as previously described (Milenkovic et al. 2008). Myelinated and unmyelinated single fibres were classified by their conduction velocity (CV), von Frey threshold and stimulus–response function. Thickly myelinated Aβ-fibres (CV > 10 m s−1) can be subdivided into low-threshold RAMs and SAMs. The median von Frey threshold of both SAMs and RAMs is 1.0 mN and 0.4 mN, respectively (Table 1). We classified afferents with conduction velocities between 1 and 10 m s−1 as myelinated Aδ-fibres and around half of such fibres can be easily classified as D-hairs receptors, which are the most sensitive mechanoreceptors, with von Frey thresholds of 0.04 mN and lower (Brown & Iggo, 1967; Lewin et al. 1992; Boada & Woodbury, 2008; Lennertz et al. 2010). The second group of Aδ-fibres, the A-fibre mechanoreceptors (AMs), respond to much more intense mechanical stimuli and characteristically only respond during the static phase of a ramp-and-hold indentation stimulus (Milenkovic et al. 2008). C-fibres with unmyelinated axons (CV < 1 m s−1) were characterized by their responses to noxious mechanical stimuli. The general physiological properties of the recorded afferents in this study, including mean conduction velocities and von Frey threshold of each afferent type, are summarized in Table 1 Among the Aβ-fibres, RAMs accounted for between 45 and 49% of the total and SAMs between 56 and 51% of the total, in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice (Table 1). These proportions are essentially identical to those found in previous similar studies on mouse saphenous afferents (Airaksinen et al. 1996; Koltzenburg et al. 1997; Carroll et al. 1998). We also noted no major alteration in the proportion of AM to D-hair receptors encountered with conduction velocities less than 10 m s−1. Thus, in our first survey of Aδ-fibres (n = 30 in each group) we found no alteration in the expected proportion found in Cav3.2+/+ mice (AM-fibres 53%, n = 16 and D-hair 47%, n = 14) compared to Cav3.2−/− mice (AM-fibres 60%, n = 18 and D-hair 40%, n = 12), Chi-squared test P > 0.3. The physiology of D-hair receptors was a special focus of this study so that an additional 44 D-hair receptors from Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice were recorded; the conduction velocities and von Frey thresholds of these extra D-hairs were indistinguishable from those listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The proportions and physiological properties of individual primary afferent mechanoreceptors recorded in wild type and Cav3.2−/− mutant mice

| Cav3.2+/+ | Cav3.2−/− | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor type | % Total (or N) | CV (m s−1) | vFT (mN) | % Total (or N) | CV (m s−1) | vFT (mN) |

| Aβ-fibres | ||||||

| RAM | 44.4% (20/45) | 13.7 ± 0.8 | 0.4 (0.4–2) | 48.7%(18/37) | 14.7 ± 0.8 | 0.4 (0.4–2) |

| SAM | 55.6% (25/45) | 12.6 ± 0.4 | 1 (0.4–6.3) | 51.4% (19/37) | 13.8 ± 0.7 | 1 (0.4–3.3) |

| Aδ-fibres | ||||||

| AM | 53% (16/30) | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 3.3 (0.4–6.3) | 60% (18/30) | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 3.25 (1–3.3) |

| D-hair | 46% (14/30) | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 0.4 | 40% (12/30) | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 0.4 |

| C-fibres | 28 | 0.5±0.03 | 3.3 (1–6.3) | 21 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 3.3 (1–10) |

| C-MH | 19 | 0.35±0.03 | 5.8 (1–8.1) | 20 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 4.6 (0.4–10) |

The proportions, average conduction velocity and median von Frey thresholds for different physiological types of afferent fibers among the Aβ-, Aδ- and C-fibre groups recorded in the current experiment are listed. Abbreviations are as follows RAM, rapidly adapting mechanoreceptor; SAM, slowly adapting mechanoreceptor; AM, A-fibre-mechanonociceptor; and C-MH C-fibre mechano-heat fibre. The population of C-MH fibres was recorded in a separate series of experiments from those in which the mechanosensitivity of C-fibres was measured. In order to focus on the phenotypes we observed in D-hair receptors, another 26 and 18 D-hair units were recorded in the wild type and Cav3.2−/− mice, respectively. CV values are means ± SEM. von Frey values are shown as a median value together with the 1st and 4th quartile range.

The mechanosensitivity of nociceptors is unchanged in Cav3.2 mutant mice

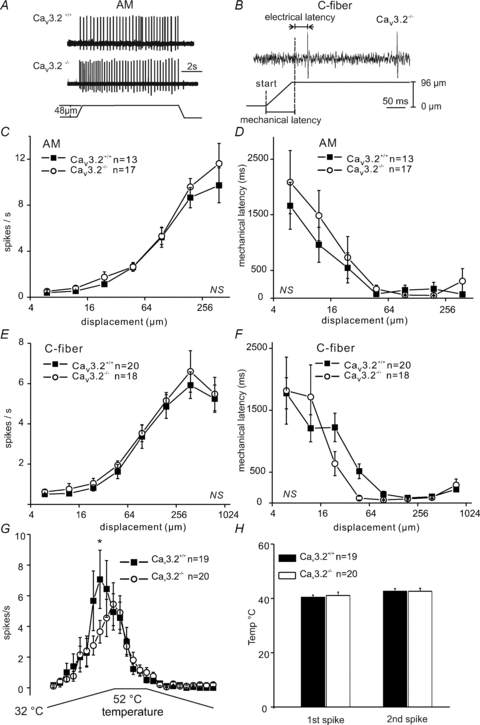

We examined the mechanosensitivity of identified nociceptors under normal conditions in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mutant mice. We subjected AM-fibres to a standard ascending series of ramp-and-hold stimuli and the stimulus–response functions obtained did not differ between Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice (repeated-measures ANOVA, F(1,196)= 0.25, P > 0.6; Fig. 1C). We also measured the mechanical latency for each stimulus in the series, the time between ramp onset until first spike corrected for conduction delay, as this is also a measure of the mechanical threshold (Fig. 1B) (Milenkovic et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2010): this parameter was also not altered in mutant mice (repeated-measures ANOVA, F(1,168)= 0.54, P > 0.4; Fig. 1D). We also recorded from a large sample of C-fibre nociceptors (see Table 1) and found that the mean stimulus–response function and mean mechanical latency plotted as a function of stimulus amplitude was not different between Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+ mice (Fig. 1E, stimulus–response function repeated-measured ANOVA F(1,252)= 0.33, P > 0.5; Fig. 1F, mechanical latency repeated-measures ANOVA, F(1,252)= 0.34, P > 0.5). In our initial study of mechanosensitivity of C-fibre nociceptors we did not routinely classify each unit according to its response to noxious thermal stimuli. Since behavioural changes in the baseline sensitivity of Cav3.2−/− of mutant mice has been reported (Choi et al. 2007), we next asked if the physiological properties of noxious heat-sensitive nociceptors are altered in the absence of Cav3.2. We therefore carried out a second series of experiments searching for heat-sensitive single C-fibre units and we quantified their heat sensitivity using defined heating ramps as previously described (Milenkovic et al. 2007). We sampled between 19 and 20 C-mechano-heat fibres (C-MH) in each genotype but found no significant difference in the firing rates during a heating ramp or in the mean temperature threshold for the first and second spike (Fig. 1G and H). However, the firing rate was transiently higher in C-MH fibres at a skin temperature of 48°C in Cav3.2+/+ compared to Cav3.2−/− and this minor change was significantly different from the wild type control data (repeated ANOVA analysis, Bonferronis post hoc test P < 0.05; Fig. 1G).

Figure 1. Stimulus response function and mechanical latencies of Aδ-mechanonociceptors in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice.

A, original records for Aδ-mechanonociceptor (AM) responses to displacements of 48 μm in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice. B, an example calculation of mechanical latency for a typical C-fibre in Cav3.2−/− mice. C and E show the mean stimulus responses for A-fibre and C-fibres for the entire ramp-and-hold stimulation for the ascending displacement series. D and F, the mechanical latency of AMs and C-fibres plotted against displacement amplitude. G shows the mean firing rate of C-MH fibres during a standard ramp and hold stimulus and H, the mean temperature at which the first or second spike occured during the ramp for both genotypes.

Impaired mechanosensitivity of D-hair receptors in Cav3.2−/− mice

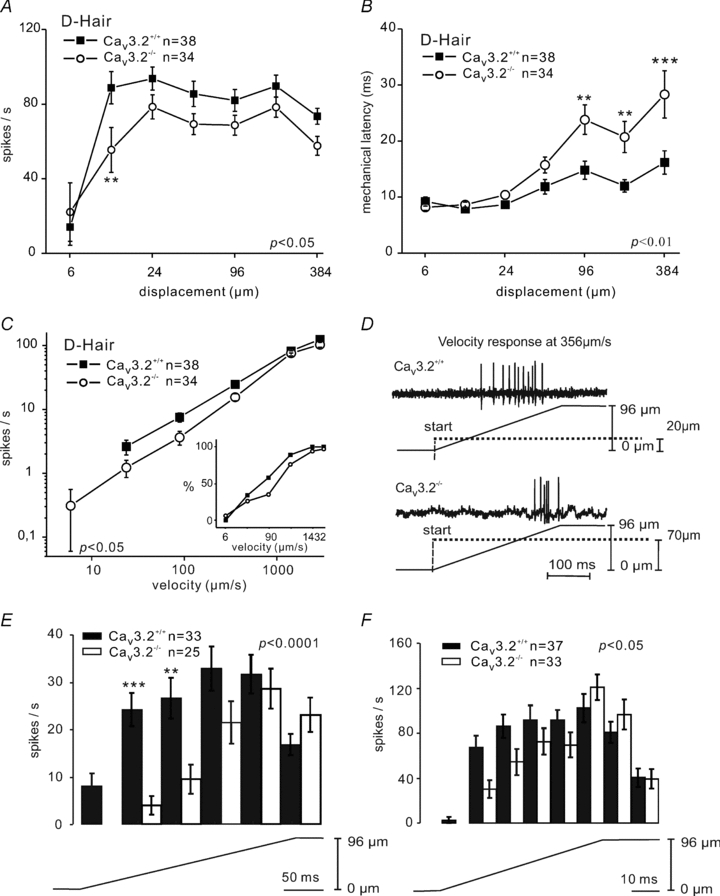

The firing frequency of D-hairs during the ramp phase of increasing displacement, at constant velocity, was consistently lower in Cav3.2−/− mice compared to Cav3.2+/+ mice; this was true for amplitudes from 12 μm to 384 μm (F(1,420)= 5.86, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). For example, at a stimulus strength of 12 μm the mean firing rate during the ramp was just 52 ± 11 spikes s−1 in Cav3.2−/− D-hair receptors compared to 84 ± 9 spikes s−1 in control D-hair receptors (ANOVA with Bonferronis post hoc test, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the mechanical latency measured for D-hair receptors from Cav3.2−/− mice was significantly longer than that found in Cav3.2+/+ mice: at stimulus strengths between 96 μm and 384 μm, mechanical latencies were more than twice as long in D-hair receptors from Cav3.2−/− mice compared to control D-hair receptors (F(1,420)= 10.32, P < 0.01; Fig. 2B), indicative of a higher mechanical threshold for activation. The longer mechanical latencies of D-hair receptors in Cav3.2−/− mice were also observed in response to a series of ramp stimuli of constant amplitude with velocities varying from 6 to 3000 μm s−1 (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Thus, our data indicated that the mechanical threshold of D-hair receptors was elevated in Cav3.2−/− mice; however, this was not reflected in an elevation in the median von Frey threshold (Table 1). This apparent contradiction is simply explained by the fact that D-hair receptors have mechanical thresholds typically much lower than the force exerted by the weakest von Frey hair used in this study (0.4 mN). We compared the velocity response of D-hair receptors in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice using a constant amplitude indentation of 48 or 96 μm with a ramp velocity that varied from 6 to 3000 μm s−1. Since not every tested unit responded to especially slow ramps, only the responding units were analysed and the percentage of units responding to each ramp velocity was plotted separately (Fig. 2C, inset).

Figure 2. Mechanosensitivity of D-hair receptors in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice.

A, phasic response function (spike frequency during the movement of the stimuli) of D-hair receptors to a constant-ramp velocity (1432 μm s−1) stimulus with increasing displacements amplitude. B, mechanical latencies of D-hair receptors in response to increasing displacement amplitude. C, the velocity response function for D-hair receptors to a constant displacement stimulus of 96 μm with a range of ramp velocities from 6–3000 μm s−1. The mean firing frequencies are shown only for those units that fired a spike during the ramp. The percentage of responding D-hairs at the corresponding velocity step is shown in the inset. D, example trace of velocity responses of D-hairs at 356 μm s−1 in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice. E and F, detailed analysis of phasic firing frequency at velocities of 356 μm s−1 and 1432 μm s−1.

The analysis of firing frequency during the ramp phase revealed that the movement response of D-hair receptors in Cav3.2−/− was also much reduced compared to that found in Cav3.2+/+ mice (F(1,280)= 4, P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). We carried out a more detailed analysis by examining the time course of D-hair firing during the ramp at two different velocities (356 μm s−1 and 1432 μm s−1). We found that the difference in firing frequency between Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− was primarily due to a delayed firing of D-hairs from Cav3.2−/− mice (Fig. 2D–F). In control Cav3.2+/+ mice, D-hairs start to fire at the beginning of the ramp and rapidly reach their maximal firing frequencies within 40 ms with a fast ramp (1432 μm s−1) and within 200 ms with a slower ramp (356 μm s−1). However, D-hairs from Cav3.2−/− mice start to fire later and more significantly do not reach their maximal firing frequency until ramp movement has just been completed (Fig. 2D–F). Despite this prominent delay in reaching maximal firing rates, the D-hair receptors from Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+ reached the same firing frequency at the end of the ramp. The time course of firing rates was significantly different between D-hair receptors recorded from Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice at both velocities (Fig. 2E and F; at 356 μm s−1, F(1,280)= 16.05, P < 0.0001; at 1432 μm s−1, F(1,345)= 3.924, P < 0.05). The proportion of D-hair receptors with a response to slow velocity ramps was lower in Cav3.2−/− mutant mice (26% to 24 μm s−1 and 97% to 3000 μm s−1) compared to Cav3.2+/+ mice (34% to 24 μm s−1 and 100% to 3000 μm s−1; Fig. 2C inset). However, the mean velocity thresholds for D-hair receptors from both genotypes were comparable (Cav3.2+/+: 292.2 ± 68.26 μm s−1, n = 38; Cav3.2−/−: 480.7 ± 94.90, n = 34 μm s−1; P > 0.1, unpaired t test).

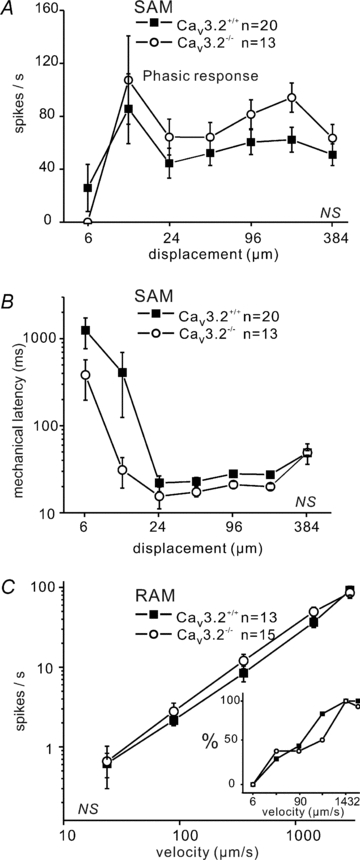

Mechanosensitivity of Aβ mechnoreceptors

Among Aβ-fibres, SAMs respond both to the ramp and the static phase of the stimulus. We therefore analysed firing rates separately for the phasic response and the total response (phasic plus static). We noted no difference in the stimulus response functions of SAMs from Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice (total: F(1,186)= 0.31, P > 0.5, Supplemental Fig. S1B; phasic: F(1,186)= 1.19, P > 0.2, Fig. 3A; static: data not shown). We did note that the SAMs in Cav3.2−/− mice tended to have a shorter mean mechanical latency at low stimulus amplitudes but this was not significantly different from the Cav3.2+/+ (F(1,186)= 3.90, P > 0.05; Fig. 3B). We have previously noted a very high degree of variation in the mechanical latency of mechanoreceptors at stimulus strengths near threshold so that a very long latency (>1 s) from just one or two fibres can considerably alter the mean mechanical latency.

Figure 3. Mechanosensitivity of Aβ-fibres.

A, phasic response function (spike frequency during the movement of the stimuli) of SAM at constant-ramp velocity (1432 μm s−1) to increasing displacements. B, mechanical latency of SAMs in response to increasing displacement amplitude. C, velocity response function for RAMs at constant displacement of 96 μm with changing velocities from 6 to 3000 μm s−1. The mean firing frequencies are shown only for those units that fired a spike during the ramp. The percentage of responding RAM at the corresponding velocity step is shown in the inset.

The second major type of Aβ-fibres is RAMs, which only fire action potentials during the ramp phase of the stimulus. The RAMs, similarly to D-hair receptors, also code the velocity of the ramp movement with increasing firing frequencies in response to increasing ramp velocity. We found no change in coding of ramp velocity by RAMs in Cav3.2−/− mice compared to controls (F(1,130)= 0.19, P > 0.6; Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. S1C).

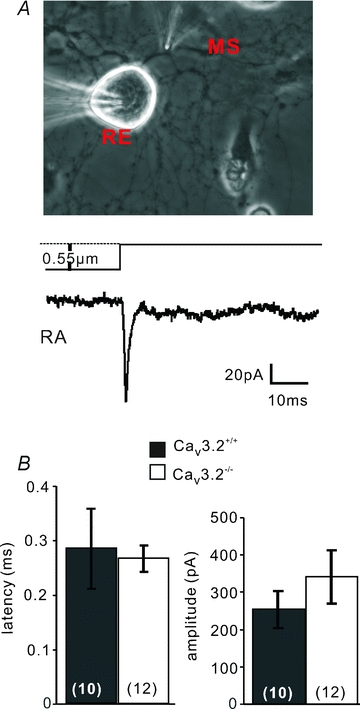

Unchanged kinetics of mechanosensitive currents in Cav3.2−/− mice

There is evidence that membrane stretch can alter the voltage sensitivity of calcium channels (Calabrese et al. 2002), and so we decided to see whether the lack of Cav3.2 might directly affect the mechanotransduction process. We therefore recorded mechanosensitive currents in acutely isolated sensory neurones taken from Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. There is compelling evidence that mechanosensitive currents measured in vitro closely reflect the mechanotransduction event in both mechanoreceptors and nociceptors in vivo (Hu & Lewin, 2006; Hu et al. 2006, 2010; Drew et al. 2007; Lechner et al. 2009; Lechner & Lewin, 2009). Under voltage-clamp conditions and in the presence of TTX, mechanical stimulation (amplitude, 550 nm) of neurites evoked fast inward currents in most sensory neurones recorded (Fig. 4A). These currents were classified according to their inactivation time constant (τ2) into rapidly adapting (RA, τ2 < 5 ms), intermediately adapting (IA, 5 ms < τ2 < 50 ms) and slowly adapting (SA, τ2 > 50 ms) (Fig. 4A). In this study we focused on putative mechanoreceptors that display an RA-mechanosensitive current, as we have previously shown that these neurones are born first and have large cell bodies, and almost all mechanoreceptors probably require this current for their mechanosensitivity (Hu & Lewin, 2006; Lechner & Lewin, 2009; Hu et al. 2010).

Figure 4. Mechanosensitive currents in DRG neurons.

A, top, bright field image of a cultured single mechanoreceptor in the whole-cell recording configuration (RE, recording electrode) with the mechanical stimulator (MS) poised to stimulate one of the neurites. Bottom, sample trace of an RA-mechanosensitive current obtained by neurite stimulation in the presence of TTX (1 μm). B, the mean latency of RA-mechanosensitive currents (left) and mean peak current amplitude (right) for RA-mechanosensitive currents in neurones recorded from Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+ mice. Number of recorded neurones is indicated at bottom of each bar.

We recorded from large sensory neurones with a narrow action potential (Cav3.2+/+: 0.64 ± 0.06 ms, n = 10; Cav3.2−/−: 0.65 ± 0.06 ms, half-peak amplitude, n = 12; P > 0.9, unpaired t test) and evoked RA-mechanosensitive currents by mechanical stimulation of the neurites (Fig. 4A). The RA-mechanosensitive current was activated within 300 μs of movement onset and the mean mechanical latency was not significantly different between neurones recorded from Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+ mice (Cav3.2+/+: 0.28 ± 0.07 ms, n = 10; Cav3.2−/−: 0.27 ± 0.02 ms, n = 12; P > 0.4, unpaired t test; Fig. 4B). The mean peak amplitude of the RA-mechanosensitive current was also not different between neurones recorded in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice (Cav3.2+/+: 253.79 ± 48.92 pA, n = 10; Cav3.2−/−: 341.20±71.44 pA, n = 12; P > 0.08, unpaired t test; Fig. 4B). We also noted no change in the activation or inactivation kinetics of the RA-mechanosensitive current between the two genotypes (not shown). We conclude that the lack of Cav3.2 in low-threshold mechanoreceptors has essentially no effect on the primary transduction that probably underlies the receptor potential in these neurones.

Cav3.2 channels regulate mechanoreceptor firing in response to ramp current injections

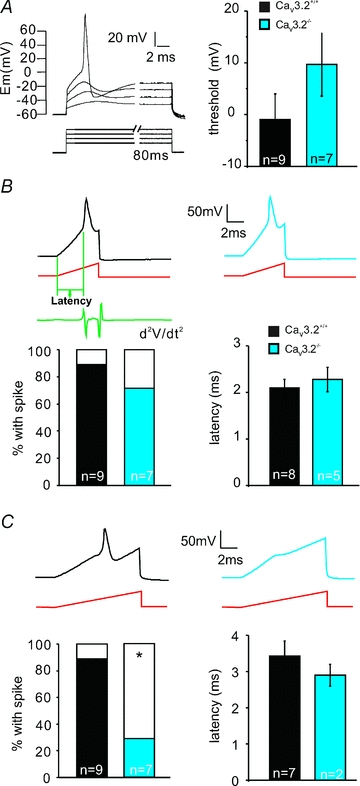

The T-type channel Cav3.2 is a LVA Ca2+ channel, which is activated at very negative potentials (∼−50 mV), close to the resting membrane potential. We have hypothesized that depolarizing receptor potentials in mechanoreceptors equipped with a high density of Cav3.2 channels might be boosted by the activation of the T-type channel before the threshold is reached for voltage-gated sodium channels (Shin et al. 2003; Dubreuil et al. 2004; Heppenstall & Lewin, 2006). One prediction of this hypothesis would be that mechanoreceptors lacking Cav3.2 channels might have a higher electrical threshold for the initiation of APs. We tested this by recording in current-clamp mode from putative mechanoreceptors in vitro. The form of the receptor potential in mechanoreceptors caused by opening of mechanosensitive channels is not known in mammals (Hu et al. 2006). Thus, we decided to inject current with different waveforms into putative mechanoreceptors in current-clamp mode using the patch-clamp amplifier, which might approximate to the time course of current flow through mechanosensitive channels. We selected cultured neurones with narrow APs characteristic of mechanoreceptors for these experiments as ∼30% of these neurones may in fact be D-hair receptors (Lewin & Moshourab, 2004). Using a series of step current injections we observed that the AP was initiated when membrane voltage around 0 mV and the mean voltage for AP initiation was not significantly different between neurones recorded from Cav3.2−/− mice (9.68 ± 6.13 mV, n = 7), compared to Cav3.2+/+ mice (−0.98 ± 4.98 mV, n = 9; P > 0.1, unpaired t test; Fig. 5A), although there was a clear tendency for higher thresholds in neurones from the Cav3.2−/− mutant mice. We performed further experiments using a more physiological current injection ramp with a final value of 5 nA and a ramp speed of either 1 nA ms−1 (duration 5 ms) or 500 pA ms−1 (duration 10 ms). We also used even slower ramp current injections of 200 pA ms−1 (duration 25 ms), but these proved completely ineffective at evoking APs in putative mechanoreceptors from both genotypes. All neurones recorded that were tested with ramp current injections had narrow APs (Cav3.2+/+: 0.63 ± 0.04 ms, n = 9; Cav3.2−/−: 0.57 ± 0.04 ms, n = 7; P > 0.2, unpaired t test). We noted that almost all the recorded neurones from both genotypes produced an AP with the faster ramp (1 nA ms−1), and the mean latency of the AP, as measured from the start of the ramp to an abrupt change in the second derivative (dV2/dt2) of the membrane potential (green trace in Fig. 5B), was not different between the two genotypes (Fig. 5B). Using a slower ramp injection (500 pA ms−1) we noted that a large proportion of mechanoreceptors from Cav3.2−/− mice did not fire an AP by the end of the ramp and this was significantly different from the neurones from Cav3.2+/+ mice, which almost all fired an AP (Fig. 5C, P < 0.05, Chi-squared test). Of those neurones that did fire during the ramp current injection, the mean latencies for the first AP were comparable between the two genotypes (Fig. 5B and C). In summary, these experiments show that current injections that have a time course similar to what might be expected after activation of mechanosensitive currents are much less effective at evoking a short latency AP in a sub-population of mechanoreceptors from Cav3.2−/− mutant mice.

Figure 5. Threshold current for somal AP initiation.

A, left panel shows stimulation protocol used to determine electrical AP threshold in mechanoreceptors (step pulses were used, starting from 500 pA with increments of 500 pA). Right panel: the mean membrane potentials at which APs are generated in Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+ mice. B, example traces of APs evoked by 5 ms current ramp injection in mechanoreceptors from both genotypes Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+. Bars on the left show the percentage of mechanoreceptors firing APs in response to 5 ms current ramp injection. Electrical latency is measured from the beginning of the current ramp to the point where the second derivative of the voltage trace reached the maximum. Mean electrical latencies are summarized in the right bar graph. C, example traces of APs evoked by 10 ms current ramp injection in mechanoreceptors from both Cav3.2−/− and Cav3.2+/+ mice. Bars on the left show the percentage of mechanoreceptors firing APs in response to 10 ms current ramp injection. Mean electrical latencies are summarized on the right bar graph. Number of recorded neurones is indicated at bottom of each bar.

Discussion

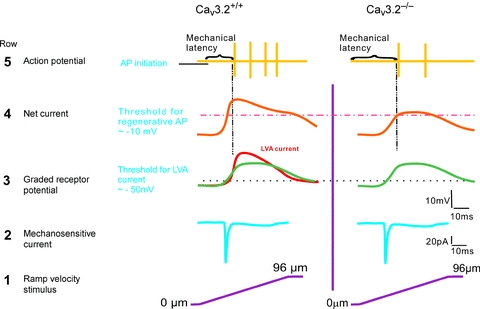

The three LVA calcium channels, Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3 are all expressed by sensory neurones in the DRG. In addition, there is clear evidence that a small sub-population of sensory neurons, in both rats and mice, express very high levels of Cav3.2 mRNA (Talley et al. 1999; Shin et al. 2003), and we and others have provided experimental evidence that this population is identical to D-hair receptors (Shin et al. 2003; Dubreuil et al. 2004; Aptel et al. 2007). In this study we have used Cav3.2−/− mutant mice to address the in vivo function of this voltage-gated calcium channel in skin sensory receptors (Chen et al. 2003). Remarkably, we find that the mechanosensitivity of D-hair receptors is dramatically reduced in Cav3.2−/− mutant mice without major changes in the physiological properties of any other type of mechanoreceptor or in nociceptors (Figs 1 and 2). This specific effect of Cav3.2 gene deletion on D-hair receptors further supports the hypothesis that Cav3.2 expression is, in the mouse, highly specific for this ultra-sensitive mechanoreceptor (Shin et al. 2003; Dubreuil et al. 2004; Aptel et al. 2007). We also examined the underlying mechanism whereby high expression of Cav3.2 channels helps to boost the mechanosensitivity and in particular the temporal coding of very small movements by D-hair receptors. We show that the activity of mechanosensitive currents in mechanoreceptors is completely unaffected in the absence of Cav3.2 channels (Fig. 4). We also show that a sub-population of mechanoreceptors recorded in vitro does not fire short latency spikes in response to ramp injection of current that may mimic the current passed by mechanosensitive channels to movement stimuli. Interestingly, the temporal window in which the presence of Cav3.2 channels appears to be necessary to sustain short latency spikes matches closely the delayed firing of D-hair receptors to moving stimuli observed in Cav3.2−/− mice (see Fig. 6 for a model).

Figure 6. A schematic diagram showing a model for AP generation in D-hair receptors in response to increasing ramp stimuli in Cav3.2+/+ and Cav3.2−/− mice.

Moving stimuli evoke inward currents (row 1, from bottom upwards), reflecting the activation of RA-mechanosensitive currents (row 2). The receptor, or generator, potential (green) caused by the inward current reaches the threshold for activation of the LVA Ca2+ channel very rapidly (dotted black line) in Cav3.2+/+ mice but not in Cav3.2−/− mice (row 3). The summation of receptor potential and transient Ca2+ currents boosts the membrane depolarization to a level sufficient for regenerative APs very quickly in Cav3.2+/+ mice (pink dotted line). In contrast, in the absence of Cav3.2 channels the same receptor potential produces a much slower depolarization that delays the initial firing (row 4). As a result, APs are generated with a much shorter latency in Cav3.2+/+ than in Cav3.2−/− mice (row 5).

Since the first description of functional T-type Ca2+ channels in peripheral sensory neurones (Carbone & Lux, 1984a,b; Schroeder et al. 1990), there has been debate about the functional role of T-type calcium channels, and Cav3.2 in particular, in sensory neurones (Heppenstall & Lewin, 2006; Jevtovic-Todorovic & Todorovic, 2006). Functional LVA currents have been recorded in small and medium sized sensory neurones with the physiological properties of nociceptors: broad-humped action potentials and capsaicin sensitivity (Todorovic et al. 2001; Nelson et al. 2005, 2007b; Lee et al. 2009). It was shown that reducing agents can acutely increase the size of T-type currents in isolated neurones, and injection of such substances into the paws of rats produced hyperalgesia to heat and mechanical stimuli (Todorovic et al. 2001). Experiments with Cav3.2 mutant mice supported a model whereby the anti-nociceptive effects of one such agent, lipoic acid, which inhibits functional T-type currents in isolated sensory neurones, are mediated via Cav3.2 calcium channel expressed in nociceptive sensory neurones (Lee et al. 2009). However, examination of pain-related behaviours in the Cav3.2−/− mutant mice indicates that global deletion of this channel protein, which includes the peripheral and central nervous system, leads to reduced behavioural responses to both noxious heat and mechanical stimuli (Choi et al. 2007). Here we show that the coding properties of identified nociceptors in the skin are largely unaffected by the genetic ablation of Cav3.2 channels. The lack of effect on the mechanosensory properties of nociceptors strongly suggests that the origin of the anti-nociceptive phenotype of these mice probably lies along the somatosensory pathway in the superficial spinal cord dorsal horn and thalamus where the presence of T-type calcium channels has also been demonstrated (Talley et al. 1999; Ikeda et al. 2003; Joksovic et al. 2006). Thus, the lack of behavioural effects of substances such as lipoic acid in Cav3.2−/− mice could also be attributed to altered processing of nociceptive information in the CNS. Similarly, there is evidence that drugs such as mibefradil and ethosuximide, as well as redox agents that attenuate T-type currents, reduce perception of painful stimuli (Bilici et al. 2001; Matthews & Dickenson, 2001; Todorovic et al. 2001; Barton et al. 2005). However, there is so far no direct evidence that the site of action of such drugs impedes the transformation of noxious heat and mechanical stimuli into electrical activity in nociceptors. Rather, the available evidence supports a model whereby these agents may alter the processing of noxious information in the spinal cord and brain. The fact that we find little evidence that the baseline properties of nociceptors are altered in the absence of Cav3.2 channels does not preclude the possibility that this channel is normally expressed in such neurones. We did, for example, note a minor reduction in the supra-threshold response of C-MH fibres to noxious heat ramps in Cav3.2−/− mice compared to control Cav3.2+/+ mice (Fig. 1G). The change in noxious heat sensitivity observed here is very minor compared to the recently described reduction in noxious heat sensitivity of C-fibres found in mice with a null mutation of the c-Kit tyrosine kinase receptor gene (Milenkovic et al. 2007). Since the elevation of the behavioural threshold to noxious heat is very similar in Cav3.2−/− and c-Kit−/− mutant mice (Choi et al. 2007; Milenkovic et al. 2007), it appears unlikely that the small change in the noxious heat sensitivity of poly-modal C-MH nociceptors, observed here, can account for the change in behavioural threshold found in Cav3.2−/− mutant mice. It is, however, possible that this channel plays other as yet unexamined roles in regulating aspects of nociceptor physiology; one possibility is that it regulates mechanical sensitization events shown to occur after UV-B skin damage (Bishop et al. 2010).

It has been demonstrated that expression of Cav3.2 alone can entirely account for the prominent T-type current found in a sub-population of medium sized sensory neurones (Aptel et al. 2007). There is now very good evidence that this T-rich population of sensory neurones is in fact identical to D-hair receptors. Here we show that deletion of the Cav3.2 channel gene leads to a specific loss of temporal encoding of moving stimuli by D-hair receptors, as well as an elevated electrical threshold for spike firing in response to physiological ramp depolarization in cultured sensory neurones (Figs 2 and 5). Neurones with a ‘rosette’ type neuritic morphology are T-rich and also require NT-4 for survival, as do D-hair receptors in vivo (Stucky et al. 2002; Shin et al. 2003; Dubreuil et al. 2004; Aptel et al. 2007). The fact that T-rich sensory neurones can no longer be identified in Cav3.2−/− mice precludes the measurement of T-type currents in cultured neurones as a marker of D-hair receptors in our experiments. We reasoned that D-hair receptors make up a significant proportion of all skin mechanoreceptors and thus we should observe a change in the electrical excitability in a sub-population of mechanoreceptors. Indeed, in this study we did observe that a large proportion of mechanoreceptors recorded in vitro did not spike during ramp current injections that mimic the receptor potential evoked by slow moving stimuli (Fig. 5). At this point we have no independent way of identifying D-hair receptors in culture so we cannot be sure that all the neurones that fail to spike to current ramps are indeed D-hair receptors. One report has described a population of medium to large sized sensory neurones from juvenile rats with narrow action potentials and very large T-type calcium currents that also display inward currents to capsaicin application (Nelson et al. 2005). The authors characterized these neurones as nociceptors primarily based on their sensitivity to capsaicin, but the narrow action potentials observed in the recorded cells are in vivo only ever found in low-threshold mechanoreceptors (Ritter & Mendell, 1992; Fang et al. 2005). Small T-type calcium currents have been recorded in putatively nociceptive sensory neurones (Schroeder et al. 1990; Todorovic et al. 2001); however, there are no data available based on targeted disruption of T-type calcium channel genes that identify which channel mediates these currents. The lack of change in mechanosensitivity of single Aδ- and C-fibre nociceptors in Cav3.2−/− mice does not support a role for this channel in the transduction of noxious stimuli in vivo. It is possible that a small sub-population of specialized nociceptors is more critically dependent on the presence of Cav3.2 channels than the majority of nociceptors. Using our sampling procedures we found no evidence for such a population of nociceptors and it is unclear how one would identify such a population at the present time.

It is well known that T-type Ca2+ channels activate at potentials near the resting membrane potential and since D-hair receptors are so ultrasensitive, it is likely that constant activation may even contribute to resting intracellular calcium (Magee et al. 1996). It is therefore possible that the effects we observed in the encoding of natural stimuli in the absence of Cav3.2 channels may in part be secondary to a change in intracellular calcium concentration and dynamics. However, our results indicate that it is membrane depolarization through activation of Cav3.2 channels that primarily contributes to the altered threshold and temporal delay in firing that we observe in D-hair receptors in Cav3.2−/− mutant mice. This model is consistent with the proposed role of T-type calcium channels in CNS neurones where such channels are for shaping sub-threshold membrane fluctuations, rebound burst firing (Llinas & Yarom, 1981), rhythmic oscillation (Gutnick & Yarom, 1989; Bal & McCormick, 1993) and pacemaker activity (Bal & McCormick, 1993; Puil et al. 1994). The loss of Cav3.2−/− in D-hair receptors primarily leads to a delay in firing to moving stimuli and a considerable slowing in the time taken to reach maximum firing frequency (see Fig. 2E and F). Interestingly, it has recently been shown that the temporal sequence of spikes in human mechanoreceptors may be critical in coding relevant information about the stimulus (Johansson & Birznieks, 2004; Saal et al. 2009). Thus, the expression of Cav3.2 channels in D-hair mechanoreceptors may serve to provide highly accurate temporal information about rapidly changing stimuli. Such temporal information may help animals, including humans, to make very rapid and accurate judgments about the speed and direction of tactile stimuli.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to G.R.L. (Le-1084/4-2). R.W. was supported by the DFG-Research Training Group ‘Neuroinflammation’. We would like to thank Dr Kevin P. Campbell for the kind gift of Cav3.2 mutant mice. We are thankful for the excellent technical assistance of Heike Thränhardt. We thank members of the Lewin lab, especially Dr Stefan Lechner and Dr Ewan St J. Smith for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AM

A-fibre mechanonociceptor

- AP

action potential

- C-MH

C-mechano-heat fibres

- c-RET

ret proto oncogene

- CV

conduction velocity

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- IA

intermediate adapting

- LVA

low-voltage-activated

- mafA

v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A

- RA

rapidly adapting

- RAM

rapidly adapting mechanoreceptor

- SA

slowly adapting

- SAM

slowly adapting mechanoreceptor

- SIF

synthetic interstitial fluid

Author contributions

R.W. carried out all experimental work, designed experiments, analysed data and prepared the figures. G.R.L. conceived the study, designed experiments and wrote the paper. Both authors approved the final version.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figure 1

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors

References

- Airaksinen MS, Koltzenburg M, Lewin GR, Masu Y, Helbig C, Wolf E, Brem G, et al. Specific subtypes of cutaneous mechanoreceptors require neurotrophin-3 following peripheral target innervation. Neuron. 1996;16:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aptel H, Hilaire C, Pieraut S, Boukhaddaoui H, Mallie S, Valmier J, Scamps F. The Cav3.2/α1H T-type Ca2+ current is a molecular determinant of excitatory effects of GABA in adult sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal T, McCormick DA. Mechanisms of oscillatory activity in guinea-pig nucleus reticularis thalami in vitro: a mammalian pacemaker. J Physiol. 1993;468:669–691. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ME, Eberle EL, Shannon HE. The antihyperalgesic effects of the T-type calcium channel blockers ethosuximide, trimethadione, and mibefradil. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;521:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilici D, Akpinar E, Gursan N, Dengiz GO, Bilici S, Altas S. Protective effect of T-type calcium channel blocker in histamine-induced paw inflammation in rat. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44:527–531. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop T, Marchand F, Young AR, Lewin GR, McMahon SB. Ultraviolet-B-induced mechanical hyperalgesia: a role for peripheral sensitisation. Pain. 2010;150:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boada MD, Woodbury CJ. Myelinated skin sensory neurons project extensively throughout adult mouse substantia gelatinosa. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2006–2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5609-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourane S, Garces A, Venteo S, Pattyn A, Hubert T, Fichard A, et al. Low-threshold mechanoreceptor subtypes selectively express MafA and are specified by Ret signaling. Neuron. 2009;64:857–870. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AG, Iggo A. A quantitative study of cutaneous receptors and afferent fibres in the cat and rabbit. J Physiol. 1967;193:707–733. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese B, Tabarean IV, Juranka P, Morris CE. Mechanosensitivity of N-type calcium channel currents. Biophys J. 2002;83:2560–2574. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75267-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Lux HD. A low voltage-activated calcium conductance in embryonic chick sensory neurons. Biophys J. 1984a;46:413–418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84037-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Lux HD. A low voltage-activated, fully inactivating Ca channel in vertebrate sensory neurones. Nature. 1984b;310:501–502. doi: 10.1038/310501a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll P, Lewin GR, Koltzenburg M, Toyka KV, Thoenen H. A role for BDNF in mechanosensation. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:42–46. doi: 10.1038/242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Lamping KG, Nuno DW, Barresi R, Prouty SJ, Lavoie JL, et al. Abnormal coronary function in mice deficient in alpha1H T-type Ca2+ channels. Science. 2003;302:1416–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.1089268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Na HS, Kim J, Lee J, Lee S, Kim D, et al. Attenuated pain responses in mice lacking CaV3.2 T-type channels. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew LJ, Rugiero F, Cesare P, Gale JE, Abrahamsen B, Bowden S, et al. High-threshold mechanosensitive ion channels blocked by a novel conopeptide mediate pressure-evoked pain. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil AS, Boukhaddaoui H, Desmadryl G, Martinez-Salgado C, Moshourab R, Lewin GR, et al. Role of T-type calcium current in identified D-hair mechanoreceptor neurons studied in vitro. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8480–8484. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, McMullan S, Lawson SN, Djouhri L. Electrophysiological differences between nociceptive and non-nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurones in the rat in vivo. J Physiol. 2005;565:927–943. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutnick MJ, Yarom Y. Low threshold calcium spikes, intrinsic neuronal oscillation and rhythm generation in the CNS. J Neurosci Methods. 1989;28:93–99. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppenstall PA, Lewin GR. A role for T-type Ca2+ channels in mechanosensation. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Chiang LY, Koch M, Lewin GR. Evidence for a protein tether involved in somatic touch. EMBO J. 2010;29:855–867. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Lewin GR. Mechanosensitive currents in the neurites of cultured mouse sensory neurones. J Physiol. 2006;577:815–828. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Milenkovic N, Lewin GR. The high threshold mechanotransducer: a status report. Pain. 2006;120:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Synaptic plasticity in spinal lamina I projection neurons that mediate hyperalgesia. Science. 2003;299:1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1080659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. The role of peripheral T-type calcium channels in pain transmission. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson RS, Birznieks I. First spikes in ensembles of human tactile afferents code complex spatial fingertip events. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:170–177. doi: 10.1038/nn1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joksovic PM, Nelson MT, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Patel MK, Perez-Reyes E, Campbell KP, et al. CaV3.2 is the major molecular substrate for redox regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in the rat and mouse thalamus. J Physiol. 2006;574:415–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltzenburg M, Stucky CL, Lewin GR. Receptive properties of mouse sensory neurons innervating hairy skin. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1841–1850. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Koltzenburg M, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Responsiveness and functional attributes of electrically localized terminals of cutaneous C-fibers in vivo and in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:581–595. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.2.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner SG, Frenzel H, Wang R, Lewin GR. Developmental waves of mechanosensitivity acquisition in sensory neuron subtypes during embryonic development. EMBO J. 2009;28:1479–1491. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner SG, Lewin GR. Peripheral sensitisation of nociceptors via G-protein-dependent potentiation of mechanotransduction currents. J Physiol. 2009;587:3493–3503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WY, Orestes P, Latham J, Naik AK, Nelson MT, Vitko I, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lipoic acid modulation of T-type calcium channels in pain pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9500–9509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5803-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennertz RC, Tsunozaki M, Bautista DM, Stucky CL. Physiological basis of tingling paresthesia evoked by hydroxy-α-sanshool. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4353–4361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4666-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin GR, Moshourab R. Mechanosensation and pain. J Neurobiol. 2004;61:30–44. doi: 10.1002/neu.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin GR, Ritter AM, Mendell LM. On the role of nerve growth factor in the development of myelinated nociceptors. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1896–1905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01896.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Yarom Y. Electrophysiology of mammalian inferior olivary neurones in vitro. Different types of voltage-dependent ionic conductances. J Physiol. 1981;315:549–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Enomoto H, Rice FL, Milbrandt J, Ginty DD. Molecular identification of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors and their developmental dependence on ret signaling. Neuron. 2009;64:841–856. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Avery RB, Christie BR, Johnston D. Dihydropyridine-sensitive, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels contribute to the resting intracellular Ca2+ concentration of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3460–3470. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Salgado C, Benckendorff AG, Chiang LY, Wang R, Milenkovic N, Wetzel C, et al. Stomatin and sensory neuron mechanotransduction. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:3802–3808. doi: 10.1152/jn.00860.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews EA, Dickenson AH. Effects of ethosuximide, a T-type Ca2+ channel blocker, on dorsal horn neuronal responses in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;415:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00812-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic N, Frahm C, Gassmann M, Griffel C, Erdmann B, Birchmeier C, et al. Nociceptive tuning by stem cell factor/c-Kit signaling. Neuron. 2007;56:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic N, Wetzel C, Moshourab R, Lewin GR. Speed and temperature dependences of mechanotransduction in afferent fibers recorded from the mouse saphenous nerve. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2771–2783. doi: 10.1152/jn.90799.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Perez-Reyes E, Todorovic SM. The endogenous redox agent L-cysteine induces T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent sensitization of a novel subpopulation of rat peripheral nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8766–8775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2527-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Su P, Kang HW, Van Deusen A, Baumgart JP, et al. Molecular mechanisms of subtype-specific inhibition of neuronal T-type calcium channels by ascorbate. J Neurosci. 2007a;27:12577–12583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2206-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Woo J, Kang HW, Vitko I, Barrett PQ, Perez-Reyes E, et al. Reducing agents sensitize C-type nociceptors by relieving high-affinity zinc inhibition of T-type calcium channels. J Neurosci. 2007b;27:8250–8260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1800-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:117–161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puil E, Meiri H, Yarom Y. Resonant behavior and frequency preferences of thalamic neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:575–582. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter AM, Mendell LM. Somal membrane properties of physiologically identified sensory neurons in the rat: effects of nerve growth factor. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:2033–2041. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saal HP, Vijayakumar S, Johansson RS. Information about complex fingertip parameters in individual human tactile afferent neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8022–8031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0665-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JE, Fischbach PS, McCleskey EW. T-type calcium channels: heterogeneous expression in rat sensory neurons and selective modulation by phorbol esters. J Neurosci. 1990;10:947–951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00947.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JB, Martinez-Salgado C, Heppenstall PA, Lewin GR. A T-type calcium channel required for normal function of a mammalian mechanoreceptor. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:724–730. doi: 10.1038/nn1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucky CL, Shin JB, Lewin GR. Neurotrophin-4: a survival factor for adult sensory neurons. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1401–1404. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA. Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1895–1911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Meyenburg A, Mennerick S, Perez-Reyes E, Romano C, et al. Redox modulation of T-type calcium channels in rat peripheral nociceptors. Neuron. 2001;31:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel C, Hu J, Riethmacher D, Benckendorff A, Harder L, Eilers A, et al. A stomatin-domain protein essential for touch sensation in the mouse. Nature. 2007;445:206–209. doi: 10.1038/nature05394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.